Family Life in the Digital Age of Globalization

Critical Reflections on ‘Integration’

1Introduction

Most people think that those who come here achieve everything immediately: work, prosperity, and a life of luxury. But that’s not how it is. The people who come here out of necessity are in for a rough time, of – let’s just say – sheer survival. When you arrive with a job, it’s different, but many aren’t that lucky. Arriving without papers, without work, without acquaintances, without friends, many don’t understand a thing. And for this reason, many have problems and separate. Because there are times when you don’t even have enough to call your kids, and even when you can live with a family member, you have to pay him for the room. And the first need that we have here as immigrants is to secure a room for ourselves, because if I don’t have money to pay for my room, where do I go then? No one gives you a thing here. Nothing. So the first thing that we usually do, or have to do, is to make sure we have a place to stay, because we can’t live on the streets. And the second thing would be money for the family, for the kids. And some people often can’t manage that. They can’t manage it. And, well, that was the start of my coming here.

Angela, Spain, July 2015146

This quote is taken from an interview with a migrant mother who had already been working in Spain for ten years by 2015, when Diana, a fellow of my research team spoke with her about her arrival in that country. Before emigrating to Spain, Angela lived in Paraguay with her husband and her two young children. With a tourist visa and tickets bought with money borrowed from neighbors, Angela managed to reach her destination in Europe, but with little money, no accommodation, and no work, let alone a work permit. During the nearly four years it took Angela to legalize her residential status, she was subjected to precarious working conditions, and was sometimes not even compensated for her labor.

Approaching Angela’s immigration experiences from a methodological nationalist perspective (Wimmer and Glick Schiller 2002) allows us to conceive of integration in terms of individuals’ inclusion in the hosting nation-state. In so doing, it becomes clear that Angela was excluded from her legal right to participation and support upon setting foot in Spain (“No one gives you a thing here”). The fact that Angela was granted a residence and work permit only after considerable time may stem from state authorities’ ambivalent and perhaps even calculated disposition towards immigration. Whether intentional or not, this way of dealing with undocumented immigrants reflects a de facto Darwinian integration policy: those who endure the irregularity, exploitation, and denial of rights in their host state prove that they are worthy of acquiring legal rights.

Angela’s experiences illustrate how demanding immigration is for individuals who “come […] out of necessity” and who, without legal support, must fight for legal recognition. Moreover, Angela’s account evinces several characteristics of contemporary migration processes, some of which can be better studied through an analytical distance from current political debates on national integration policies. Indeed, a two-fold shift in perspective opens up further insights into these migration processes. ‘Zooming in’ on Angela’s experience reveals that migration is not a process that can be reduced to the movement of individuals across national borders with the aim of permanently changing one’s place of residence. Before Angela physically moved from Paraguay to Spain, she had already been part of a transnational migration network. Her brother, who had been in Spain for several years, encouraged her to immigrate there, and when she arrived, he supported her as she established herself. And by borrowing money for her trip to Spain from neighbors in Paraguay, she incorporated these neighbors into her transnational migration network. As a result, they acquired certain claims to the success of her migration project. ‘Zooming out’ of Angela’s migration experience and situating her networks within an overarching global social system reveals how both the position of Paraguay in global markets and its postcolonial relationship to Spain have shaped current living conditions and migration processes.

Using Angela’s migration story as the primary source material for this chapter, I will clarify what can be gained by employing a two-fold, shifting perspective on migration processes and practices. I begin with a conceptual clarification of the terms ‘integration’ and ‘migration’ in order to analyze contemporary migration processes and practices at a distance from political concerns. The remainder of the chapter is organized according to my approach of shifting between ‘zooming in’ and ‘zooming out.’ Returning to Angela’s subjective experiences as a migrant, I zoom out to contextualize her account within the broader socioeconomic conditions of her home country. Taking Paraguay as a model for an actor-centered global perspective on migration and integration, two questions arise. The first concerns units of analysis in the study of integration; the second concerns practices of distant care (Baldassar and Merla 2013) and their impact on integration. Zooming into Angela’s account illuminates the experience of starting and maintaining a family in contemporary Paraguay, as well as the path to becoming a transnational family. When stating that she had failed to send money to her family or even call her children because she did not earn enough during her first time in Spain, Angela refers to two constitutive features of contemporary transnational family life – remittances and communication technologies – which I examine accordingly. Finally, I summarize my findings by analyzing the social structure of transnational families and the overlapping layers of integration in which they are embedded.

2Migration and Integration: Conceptual Clarifications from an Actor-Centered Global Perspective

Around the turn of the millennium, an essay by Andreas Wimmer and Nina Glick Schiller (2002) attracted considerable attention and set off a self-critical debate around basic theoretical and methodological premises in the social sciences. With the fundamentally critical concept of ‘methodological nationalism,’ the authors diagnosed a general and a migration studies-specific lack of reflexive distance from nationalistic ideologies and their constitutive significance for the self-conception and construction of modern societies. The nation-state as an organizational political form is not contextualized as a historical phenomenon, but rather presupposed as a universal social organizational form of modernity, and is reified as such in sociological terms and methods. This is reflected in comparative studies’ assumption that nation-states are natural unities, and in the fact that transnational processes are systematically tuned out. In other words, these processes are only ever perceived as cut out from each state territory being researched. As a result, an overview of migration phenomena in both political and social-scientific thinking mostly assumes a spatially connoted social order whose interior and exterior are determined through a sovereign nation’s territorial borders. From the perspective of an adoptive nation, migrants are the foreigners who come from elsewhere and plead for entry and participation in that nation, whether in the education system, the job market, or the social sphere. The foreign-cultural baggage that is attributed to immigrants offers locals the opportunity to present themselves as a cultural unity in opposition to the foreigners, and/or to obstruct these foreigners, thereby confirming the members of each group. The proximity of research in the social sciences to nation-state notions of normality in society is also reflected in the prioritization of questions regarding social, or more specifically, cultural integration or segregation.

Upon the development of methodological nationalism, migration and integration became problematic terms in the humanities due to an increasing awareness of how similar scientific terms were to political terms. It is therefore necessary to redefine the pertinent terms and to develop new approaches for researching the contemporary practices and social dynamics of migration and integration. In this respect, I suggest starting with a micro-perspective on individual cases, and tracking the interactions between subjects’ movements, networks, practices, and values in order to understand how each of these elements creates and shapes units of integration in their own right. This micro-perspective on individual cases must thus be contextualized within a global frame of analysis to enable scholars to account for how different social units of integration, in which individuals are situated, mutually influence one another. I prefer a restriction of the term ‘integration,’ and will conceptually differentiate ‘migration’ into three distinct modes of mobility.

2.1Integration

The concept of integration has long been a controversial topic in both politics and scientific discourse. Debates on methodological nationalism caused a shift in perspective in some factions of migration studies, resulting, in part, in a critical stance towards integration, and in some cases, in an outright rejection of the term (see Faist and Ulbricht 2014). In the context of contemporary refugee immigration to Europe, the paradigmatic status of integration has been strengthened again, including a return to assimilation claims in the debate (Koopmans 2017). But what does integration mean? Many scholars have attempted to define the concept, and in so doing have made a consistent definition progressively more difficult. Some scholars define the term in accordance with its undisputed etymological core. Deriving from the Latin word integrare, integration means the (re)establishment of unity (Scheller 2015, 23). Albrecht Koschorke points out this definition’s nostalgic connotations, which is evident not only in the concept itself, but is also reflected in its use. According to him, this longing for an earlier state refers to the identikit of a sovereign territorial state, which houses a culturally homogeneous civil society: a form of government that appears threatened by migration and other globalization processes. He concludes that it is actually “a ubiquitous and diffuse fear of disintegration that gives the demand for integration its emotional impact” (Koschorke 2014, 220, my translation). The emotional impact resulting from an experience of the loss of an idealized society burdens the analytical value of this term. From a more objective standpoint, the German sociological lexicon defines integration as the unity of a system established by the binding and consensual determination of positions in the system’s structure, as well as by roles in the system’s division of labor and duties (Epskamp 2007, 301).

There are three advantages to this definition. The first is its renouncement of a concept of society that makes it apt for every social unit, be that the nucleus of a family, a cross-border social network of mutual support, a regional or global market, or the world system of nation-states as potential units of integration. This quality also enables interactions between these layers of integration to be taken into consideration. Second, this definition does not focus on individuals or groups, like migrants, as the object of integration, but rather focuses on the system itself. The third benefit of this definition is that it takes inequality into account as a potential structural feature of social systems. As such, it does not define any normative claims on inclusion in terms of equal participatory rights for each element of the system, i. e., each member of society, but solely in terms of a consensual and binding social order vis-à-vis social positions and labor division. Indeed, this definition distances itself from any political usage of the term, which is the equation of society to nation-state to unit of integration. Furthermore, it enables the empirical exploration of the relevant units of integration in each individual case, and the study of the dynamics of social positioning in a multilayered social field. In sum, this precise definition is freed from any idealizations about society and may thus serve as a working concept in the following analysis.

2.2Migration

The present study differentiates migration into three interdependent modes of mobility: corporeal, medial, and social mobility. As mentioned previously, this modification is necessary in order to detach sociological from political relevancies, with the ultimate aim of foregrounding the inner logic of migration processes. Moreover, the constitutive import of ‘media’ for practical and discursive modes of socialization emerges through the differentiation and analysis of relationships between varying forms of mobility.

Corporeal mobility encompasses all possibilities regarding the decision to select one’s location for life, work, study, and/or temporary residence, and with it, the necessity and ability to cross national borders. Here, the administrative classification according to the type of migration and the respective legal provisions and procedures is somewhat decisive. Is a border crossing politically, economically, or touristically motivated, or is it classified in the framework of international agreements on educational exchanges? The geographical origin and socioeconomic status of immigrants is decisive in attributing intentions to migrants, and in judging the legitimacy of their reasons for immigration.

Conversely, social mobility refers to the concrete alterations of social status that could be associated with a migratory act. Are qualifications in the destination country recognized as nearly equivalent, or are they devalued or upgraded? How are migration as a practice and migrants as social figures represented in public discourse? And in this process, in what ways are countries of origin, phenotype, religion, reason for migration, and other criteria roughly differentiated? Especially in the context of transnational lifestyles, paradoxical effects often reveal themselves with regard to social positioning.

Finally, medial mobility signifies the possibilities of access to and the competent use of media. These include cultural semiotic systems, i. e., language, which enable the crossing of linguistic borders, as well as information and communication technologies (ICT) that are required to cross spatio-temporal borders. In the context of migration, access to ICT is relevant in many regards: first, to obtain information and orientation vis-à-vis possible destinations and migration routes; second, to remain informed from afar on current events in the homeland, and integrated in the relevant discourses in the place or places to which one is socially connected; third, to shape social relationships, the coordination of which shifts in the process of migrating and must be readjusted; and fourth, to expand the possibilities for crossing linguistic borders through, for instance, the use of language-learning and translation applications. Before illustrating how transnational families practice these distinct forms of mobility and how these forms influence each other, I propose that changing perspectives, and zooming out on Paraguay’s global social position, will contextualize contemporary Paraguayan living conditions and pinpoint how they shaped Angela and her family’s migratory practices.

3Zooming Out: Paraguay – ‘Living Boundaries’ and Global Soy Fields

A landlocked country in the center of South America, Paraguay borders Bolivia, Argentina, and Brazil. It is smaller than California with roughly 407,000 square kilometers, and its estimated 6.8 million inhabitants make it one of the least populated nations in Latin America. Despite its status as a relatively unknown and powerless state in cultural, economic, and political terms, Paraguay has acquired an important position in the global market as the world’s fourth largest exporter of soy (Guereña 2013, 15). In this context, Oxfam International Executive Director Jeremy Hobbs has spoken out on Paraguay for being one of the countries with the least equitable land distribution (see also Bareiro 2004). Indeed, 77 % of Paraguayan land ownership is concentrated in the hands of only 2 % of the population, with 40 % of the population still living in rural areas (Hobbs 2012). In recent years, soy production has rapidly expanded, further deepening the inequality of land distribution. This is reflected in the Gini index147 , which showed an increase from 0.91 in 1991 to 0.94 in 2008 (Guereña 2013, 9). Because nearly half a million hectares of land have been turned into soy fields annually, thousands of rural families have been evicted as a result of this elevation in soy production. With the demand for soy still climbing – particularly in China and Europe, where soy is used mainly for cattle feed and biofuel – one may forecast a further concentration of land in the hands of few and the expansion of monocultural soy-based agriculture (Guereña 2013, 9). To be sure, Paraguay is a globalized territory largely controlled by transnational agribusiness, rather than a sovereign nation able to care for its inhabitants. On the contrary, the social and environmental consequences of the expansion of soy cultivation as well as cattle breeding for the world market148 have increasingly manifested themselves in the rise of sick people, displaced communities, murdered peasants, polluted rivers, logged forests, and, particularly pertinent to this study, growing migration rates. In short, the global fields of soy cultivation cause severe social problems that require transnational solutions, such as migration.

In 2003, the global Swiss agribusiness Syngenta Corporation published an advertisement that cynically captured Paraguay’s fateful position in the global market. The advertisement consisted of a map on which a large, shaded area encompassing Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Uruguay was called The United Soy Republic. The heading of this advertisement, Soy does not know borders, hints at practices of illegal land appropriation from so-called Brasiguayos. These Brazilian landowners buy Paraguayan territories in the border zone to cultivate soybeans; in so doing, they effectively expand the Brazilian frontier in the direction of Paraguay. Lenient laws and politics also attract foreign investors. Arantxa Guereña estimates that “at least 25.3 % of the country’s agricultural and livestock land is owned by foreigners” (Guereña 2013, 14). These processes of land concentration and expropriation are connected to the colonial history of both states and reflect a continuance of power relations. Framing Paraguay’s current situation in the context of its colonial and postcolonial development reveals that Paraguay never had the chance to develop into a nation-state following Anthony Smith’s definition: “a named community of history and culture, possessing a unified territory, economy, mass education system and common legal rights” (Smith 2004, 183). As I discuss elsewhere in greater detail (see Greschke 2012), the sovereignty of the Paraguayan state has always been under the demographic, cultural, economic, and political pressure of transnational influences. Although formally acknowledged as a nation-state, Paraguay empirically consists of a territory accommodating a mixture of sociocultural organizing forms, including Japanese, Brazilian, and Mennonite colonies, as well as contemporary translocal migration communities. Its political and economic power relations are strongly shaped by historical transnational relationships and loyalties, which resist attempts at national frontier demarcation, and have instead been creating ‘living frontiers’ (Clementi 1987). These living frontiers ultimately make Paraguay a weak state structured on blatant social inequality, fixing the country’s position quite low in the global social structure of an already “terribly unequal” world (Brock and Blake 2016), and at the same time, expelling Paraguay’s population.

4Zooming In: Threats to Starting and Maintaining a Family in Paraguay

Due to all the problems that I’ve had with each birth, we have been financially ruining ourselves. In Paraguay, medical care in hospitals is all at one’s own expense. Because I had three consecutive births, we were stuck with a lot of expenses, and, ever since I had the third one, we’ve remained in ruin. It’s been practically a constant struggle to survive, with three children and losing the house, losing the job, and losing all business. Because everything has gone bankrupt, it’s too much with three children. I had to make the decision with my heart in my hand, and decided to look for a better future for my children, and I had to have courage, because there was no way at that time. Angela, Spain, July 2015

When asked about her situation in Paraguay and the reasons for her migration, Angela discusses precarious living conditions and the powerlessness of national policy to support its constituents. According to a report on human rights in Paraguay, nearly half of the nation’s inhabitants lived below the poverty line in the year before Angela emigrated, and an increasing number sought salidas individuales – individual solutions – to escape the crisis. Salidas individuales not only alludes to rising rates of migration, but also to a rising number of suicides (Bareiro 2004, 14). In Angela’s account, ironically enough, starting a family is the main reason for the family’s economic plight, and Angela’s separation from her husband and children seems to be the only way to preserve her family. Angela’s account reveals the precarity of human life in Paraguay, as well as state authorities’ inability to provide for citizens’ basic needs and safety. Her experiences demonstrate the logic of transnational migration practices in terms of strategies for coping with poverty.

The World Bank recently estimated that in 2013, 14.8 % of Paraguayan citizens lived and worked abroad, primarily in neighboring Argentina, followed by Spain, Brazil, and the United States. During the course of the economic crisis in Argentina, a particularly large number of people migrated to Spain, a country known to Paraguayans as the mother of the fatherland. But even if Spain is much farther from Paraguay then Argentina, a large part of migrants do not leave their family or local community, they do not emigrate from Paraguay, nor do they immigrate to Spain in the classical sense of the terms. As Angela’s own account indicates, a considerable number of people ‘transmigrate.’ Transnational migration is a concept that was introduced by social anthropologist Nina Glick Schiller and her colleagues in 1994 (Basch, Glick Schiller, and Szanton Blanc 1994). This term refers to cross-border mobility practices that create social structures transcending physical boundaries in the familial, economic, political, health, and symbolic spheres. The transnational social spaces (Pries 1998), within which transmigrants organize their lives (Basch, Glick Schiller, and Szanton Blanc 1994), stretch from the migrant’s present place of residence to other places (of origin and/or belonging) in other nation-states. Angela’s case distinctly indicates that transnational migration often refers to transnational families, which Deborah Bryceson and Ulla Vuorela (2002) define as families that “live some or most of the time separated from each other, yet hold together and create something that can be seen as a feeling of collective welfare and unity, namely ‘familyhood,’ even across national borders” (Bryceson and Vuorela 2002, 3). The mobility practices of transmigrants bring national systems of gender-, class-, and ethnicity-related inequality into contact (Gregorio 1998). The nation-states in question are, in turn, usually disparately related to each other through the distribution of material and immaterial resources, political and economic power, prestige, as well as the “development” of and influence on global policy and economy (see Kaneff and Pine 2011). In brief, transnational migration often denotes mobility practices motivated by a prosperity gap between the country of origin and the country of destination. In Angela’s case, this prosperity gap manifests itself in the prospect of much higher earnings in Spain than would be possible for her in Paraguay. Accordingly, the logic of transnational family practices that unfolds between nation-states tied together by a wealth gap is as follows: one or more family members move to a wealthier country for work and send part of the money back home to the family. Because the earnings in the wealthier country are relatively high compared to the cost of living in the home country, these so-called remittances often allow the family to meet their basic needs while advancing socially.

To the extent that migration rates have risen over the last few years in Paraguay, remittances have constituted a growing share of the gross domestic product. In 2009, more than 10 % of Paraguayan households had family members abroad, and more than 12 % of these households received remittances from them (Gómez and Bologna 2014, 435). From 2002 until 2012, the number of remittances grew steadily, eventually reaching up to $ 634 million in 2012 (World Bank 2016). Remittances are the third largest source of cash income in the country, following only the export of soy and meat. Whereas the money that is earned with soy and meat remains in the hands of a few landowners and transnational agribusiness, remittances are distributed among the larger population, including the most vulnerable, who would live in extreme poverty without them (Gómez and Bologna 2014).

5Zooming Out: Remittances as Micropolitics of Economic Redistribution

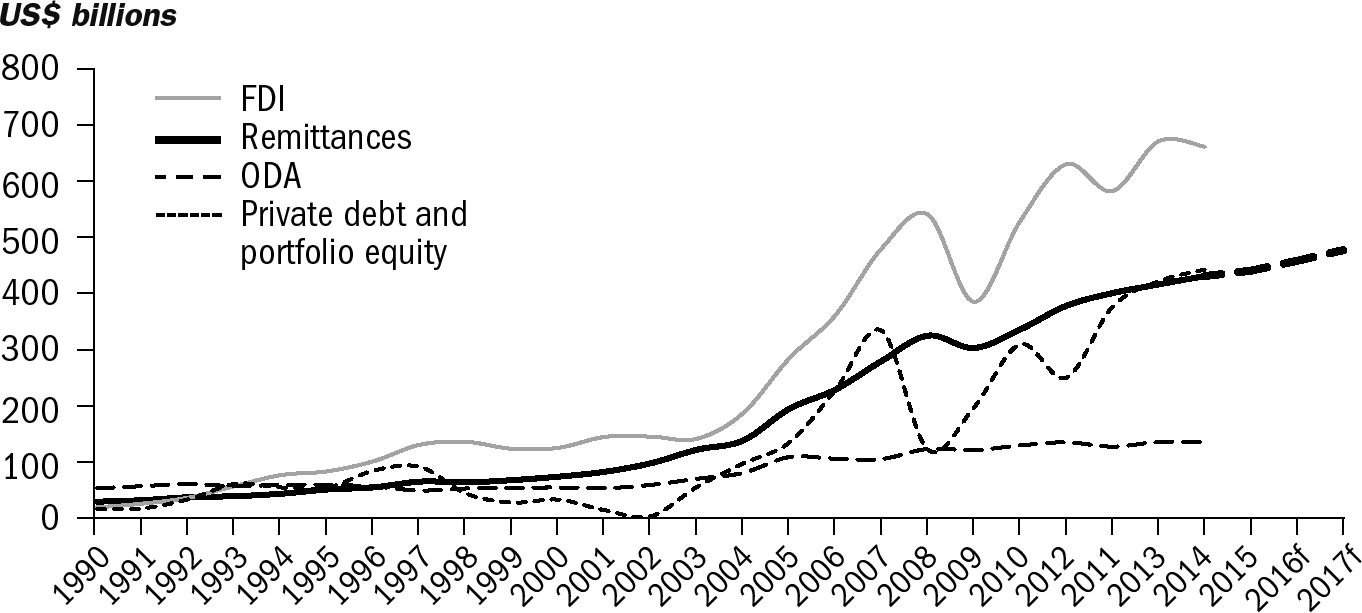

As the World Bank report from 2016 establishes, the sending and receiving of remittances has markedly increased in Paraguay and worldwide since 1990 (see figure 1). A global perspective on these money transfer flows demonstrates a distinct division between sending and receiving countries in terms of global wealth stratification (Kofman 2008). In other words, remittances can be understood as a micropolitics of economic redistribution, which is significant for reasons beyond the absolute quantity of money transferred. Remittances significantly exceed official development aid and other sources of foreign investment and “constitute reliable sources of foreign exchange earnings” (World Bank 2016, 17). Remittances are therefore classified as a foreign income source that in receiving countries is “less volatile and more stable than all other external flows” (World Bank 2016, 17Note: ). Because this micropolitics of redistribution contributes considerably to the mitigation of poverty in receiving countries (Adams and Page 2005; Gómez and Bologna 2014), remittances have attracted the attention of various international organizations in the last few years. In 2015, The Fund for Agricultural Development even declared June 16th the International Day of Family Remittances, which “is aimed at recognizing the significant financial contribution migrant workers make to the well-being of their families back home and to the sustainable development of their countries of origin.”149 Remittances not only cover the migrant and his or her family’s basic needs, but can improve the family’s social position in the home country, or at least in their local community, by improving the family’s (and especially the children’s) access to health care and education, by building houses, and by investing in businesses (World Bank 2016). When migrants spend money on community development, the resulting improvements often impact their families’ neighborhoods or social environments (Smith 1998). If, for instance, a family receiving remittances is the first in the village with Internet access, non-transnational families in the village also benefit from this migration-induced technological development (Greschke, Dreßler, and Hierasimowicz, 2018).

6Zooming In: Remittances and the Overlapping of Distinct Integration Units

In her account, Angela’s understanding of remittances dictates both the priorities she sets and her justification for the use of her earnings. In her view, “money for the family, for the children” is second only to a “place for her to stay.” Even so, Angela seems to feel that the order of her priorities needs further clarification, and she spends nearly two full minutes and more than two hundred words attempting to explain why she must first pay for her own room before sending the remainder of her earnings to her family. Why does she make such an enormous effort to rationalize a seemingly obvious matter? To whom does she address her account? One may assume that the interviewer is not the main addressee; rather, the interview offers an opportunity for correcting a misconception of her as a migrant mother who does not care for her children. Her account indicates an overlap of two conflicting integration units: the new one, in which she is involved as an undocumented migrant; and the old one, in which she is involved as a mother who has ostensibly frustrated her family by not sending money immediately upon arriving in Spain. From the family’s point of view, the mother must compensate for her physical absence with financial support, since this was the precondition for her migration. To be sure, transnational migration alters the family system’s division of labor, defining the mother’s role primarily by her work outside of the home, which ensures the family’s economic basic security. When the mother’s money fails to arrive, this may mean the total absence and exclusion of the mother from the family system.

Earning, saving, and sending as much money as possible for remittances; receiving and spending remittance money on family matters; and accounting for how that money was used are elements of one of the most crucial practices of integration in transnational family systems. This practice restructures the distribution of tasks within the family system, as well as the social positions of the family members within and beyond it. From the migrant mother’s point of view, she must take care of herself in order to continue taking care of her family. As Angela says: “The first need that we have here as emigrants is to secure a room for ourselves […] We can’t live on the streets.” Without a doubt, living on the streets is uncomfortable and, particularly for women, unsafe. Furthermore, the deviance associated with homelessness attracts the attention of authorities, potentially jeopardizing the undocumented migrant’s stay. Since migrants without papers constantly run the risk of being identified and expelled as ‘illegal,’ they must remain as invisible as possible, which naturally entails not attracting attention as a homeless person, but also ensures minimal self-inclusion in the labor and housing markets. Indeed, undocumented migrants generally have no legal rights to personhood in their host countries. Upon first arriving in Spain, Angela had to totally exclude herself from her family system in favor of the host country’s work and housing subsystems in order to remain unnoticed by the authorities. During that time, she experienced social descent within both integration units, as well as strong restrictions in terms of corporeal and mediated cross-border mobility. She was not able to travel, to send money, or even to phone home, since, as she phrases it, “sometimes one does not even have enough to call one’s children.”

Besides indicating her lack of mobility, Angela’s statement suggests the importance of communication technologies for the emergence and maintenance of transnational families, with migrant mothers taking on the additional responsibility of maintaining a communicative relationship with their children. In her comparative study of undocumented and documented migrant women in Spain, Asunción Fresnoza-Flot finds that “[a]ll respondents have made sure that each member of their family possesses a cellular phone and are usually the ones paying for the cell phone bills of their children by including this amount in their monthly remittance” (Fresnoza-Flot 2009, 260). By thus facilitating a communicative relationship and providing media equipment for their children, migrant parents set up the infrastructure for modes of remote parenting which include and go far beyond the aforementioned economic care practices, as will be discussed in the following section.

7Being Here and There: Communication Technologies and Family Integration

On May 16, 2007, on the occasion of Mother’s Day, an article on the feminization of migration in Paraguay was published in the online version of the Paraguayan newspaper Ultima Hora.150 The article caught my attention due to two quotes. The first one was from children whose mothers worked in Spain. When asked what they would do on Mother’s Day, one child responded: “We will send her an e-mail. Dad is scanning a card with a heart that I made. I say to her there that I love her and miss her and lots of other things. […] We go as often as possible to the Internet cafe to go online and talk to her and see her (webcam). She got thinner.” The second quote was from educators reporting on a project seeking to improve children’s rights. The participating children were asked to draw a picture of the ideal community in which they would like to live. The educators said: “They mostly drew telephone booths and explained to us that they would like to have one so that they can speak to their mother who is in Spain.” In both instances, the essential role that media-based communication, as well as telephone and Internet use, plays in the organization of transnational family life comes to light. Steven Vertovec (2004) describes an accordingly significant increase in international phone calls, which he attributes to a parallel increase in transnational migrants. While general cost and tariff reductions and migration-related services would have made it easier to maintain transnational relationships in the long term, the advent of the Internet and, even more critically, the smartphone accelerated this process of mutual influence between corporeal and mediated forms of mobility and family care. It is, indeed, this same generation of transnational families that we encountered in our field research on the mediatization of parent-child-relationships in Spain in 2015.

When I arrived, there was already Orkut. First came Orkut; you would get in and open and it would be full of messages. Then came Messenger and there you could already be seen in the Messenger, after that came Facebook and then Skype […] and now WhatsApp […] We use everything and my kids over there have everything too […] Now it is easier because everything is on the phone […] So I am here with my body, but my whole mind, my heart, my thoughts, are there as if I was there. And it is a continuous, steady condition, it is never broken.

Alicia, Spain, July 2015

In the above quote, Alicia, another Paraguayan migrant mother who had been living in Spain for nine years by the time of our interview, describes this accelerated phase of ‘mediatization’ (Krotz 2007) in which she participated when migrating to Spain. Despite being separated by more than 5,500 miles from her four underage children in Paraguay, she does not believe herself to be distant from her children. The high degree of media mobility she achieves through a combination of different platforms – namely, Facebook, Skype, and WhatsApp – and the possibility of always being available for her children allows Alicia and her family to mutually participate in one another’s daily lives. However, this very technological connectedness makes her feel a decoupling of her working body and caring mind, with her working body being housed by her employer in Spain and “my whole mind, my heart, my thoughts” by her beloved family in Paraguay. As in Alicia’s case, technological advancements have enabled a growing number of transnational parents around the world to maintain their care duties in their children’s daily lives. They can be present when their children need advice, someone to talk to, or someone to play with. They are responsible for sending enough money and providing the technological infrastructure of family life, but they are also entitled to monitoring financial expenditures, the children’s educational progress, and their well-being. Sending remittances has also been streamlined through smartphone technologies, as telecommunication enterprises now offer money transfer services with mobile remittance applications that are cheaper than traditional ones. In brief, digital technologies can facilitate the integration of the family system by granting the migrant parent a more sophisticated role in his or her children’s lives, including but not limited to the duty of providing for their economic security. However, these technologies are no guarantor of family integration, despite what the advertising campaigns of companies such as Skype151 and Ria152 suggest. Since the rise of transnational families promises to open lucrative market segments, interested companies tend to produce idealized imaginings that do not necessarily meet the reality of transnational family life.

According to our findings, next to the aforementioned technologies, human ‘media’ are immensely important for the success of familial integration under transnational conditions. The younger the children are, the more the family depends upon caretakers in the children’s place of residence who not only ensure their care, but model the involvement of the physically absent parent. Technology alone does not enable the parent’s presence in the children’s daily lives; producing and regulating “connected presence” (Licoppe 2004) is an elaborate and specialized process, which, the younger the children are, depends all the more strongly on a third person. Following her temporal exclusion from the family system, Angela had to endure the bitter experience of no longer being allowed her role as wife and mother. As she reports, her husband extracted her from the lives of her children as a person and as an actor playing the culturally prescribed motherly role. When, after her initial difficulties in Spain, Angela began to send money and to try to restore her communicative relationship with her children, her husband accepted the money and used it to provide for the children. However, contact with the children proved to be difficult, and Angela held her husband responsible, blaming him for having hindered her communication with her family. It was only after Angela traveled to Paraguay without warning that the situation became clear to her. She learned from her children that their father had led them to believe that their mother had left them, and that he had earned the money on which the family lived. By depicting Angela thus, the father succeeded in excluding the mother from the family system, simultaneously claiming her money as his and using her migration to rehabilitate his own faltering social status. In their internal relationship and with respect to the direct social environment of the family, he could meet the expectations of a conventional patriarchal family arrangement, which encourages the man alone to occupy the role of provider. When Angela visited Paraguay, she showed her children copies of the money transfers that she had carefully retained to prove to them that she had fulfilled her maternal responsibilities the entire time she had been away. After the passage of so many years, she reports, it was nevertheless very difficult to regain her children’s trust and to rebuild her relationship with them. Once again, communication technologies – above all, the smartphone – have facilitated Angela’s attempts to reestablish a trusting relationship with her children.

They have grown older […] they already have their own mobile phones and they have WhatsApp, and although they often do not answer my calls, well, I know that they are there, and if anything happens, they will let me know immediately. It’s not like before, when they had to depend on their dad to talk to me.

Angela, Spain, July 2015

In the above quotation, Angela indicates the difference that her children’s ages and their personal access to communication technologies make in her situation. When the children were younger, their father was the coordinator who could enable, or disable, an intimate relationship between Angela and her children. When the children grew older, Angela had the opportunity to establish a more exclusive relationship with them. However, this was only possible under three conditions: first, she had to be physically present at least once to reconnect with her children and to provide evidence – with her body and copies of money transfers – that she had always complied with her care duties, despite her husband’s assertion of the opposite. Second, she had to and still has to provide them with their own smartphones and permanent Internet access to facilitate their communicative mobility and independence from the father. Third, she must continually exert herself to maintain their confidence in her presence as a mother. While she describes the relationship with her son as intense yet conflicted, because “teenager are a bit rebellious,” she explains how she has been working towards a stable, close relationship with her daughter:

Well, I have been conquering my daughter with stories. I talk about when I was pregnant with her, the things I wanted, the things I did. I told her the beginning […] of how much I wanted to have a child, I even dreamed of it. […] The conversation I have been generating with her has changed her [attitude] towards me […] So what I do is talk, constantly be connected, tell her what I’m doing, where I am, even up to what I’m eating or what I’m preparing. I leave on the speaker [of the smartphone] or I record [videos] of the things that I’m doing and send them. Then she’s sure that I’m not here wasting time at nightclubs.

Angela, Spain, July 2015

Angela describes two modes of reconnecting with her daughter. The first consists of an invitation on an imaginative trip to the conception of the relationship between mother and daughter, Angela’s firstborn. Locating this conception even before the mother was pregnant, the quality of their relationship is granted through the mother’s great desire to have a child, which manifests itself well into her dreams. This communicative relationship, which she very appropriately denotes as conversación, virtually counteracts the daughter’s memory of being left by her mother as a small child and, thus, of not being wanted or loved by her. With her cuentos (stories), Angela transcends the child’s memory while simultaneously effacing the father’s role in the conception of the mother-child-relationship. He is not presented in her stories, since her stories embody her wish to have children, and her pregnancy. But while this conversación transforms the relationship between mother and daughter, it alone does not suffice, and their relationship requires constant updating: the mother must perpetually reassert her maternal presence and orientation towards her children’s wellbeing. She is always ‘on,’ so to speak, painstakingly documenting and letting her daughter continually follow her daily routine in order to prove to her that she is not in Spain to have fun, as the father claims, but to provide for the well-being of her children.

8Conclusion

In this chapter, I have discussed the significance of integration in transnational families. By approaching an individual case through an actor-centered global perspective, I have demonstrated how transnational migration creates parallel processes of inclusion and exclusion in different social systems, which are asymmetrically intertwined within one overarching global social system. Social positioning has become a multilayered process producing social decline and rise, a phenomenon Rhacel Salazar Parreñas (2001) coined as “contradictory class mobility.” When analyzing the social structure of transnational families, it is therefore important to consider that a great deal of the world and its subsystems are already highly globalized, through global markets and production processes and transnational companies and organizations. The infrastructure for global communication and mobility is also highly developed, at least in technological terms. On the other hand, the degrees of physical freedom to move have always been distributed disparately and are strongly contingent upon nationality. Since the global social system consists of nation-states, citizenship becomes a kind of social escort for positioning individuals within a global social structure. Bearing this in mind, strategies of family welfare can be interpreted as modes of inclusion in a globalized society, the borders of which do not necessarily correspond to the formal borders of nation-states. Transnational family care practices are provoked by growing social inequalities on a global scale and are reinforced by advancing communication technologies that enable the compression of relationships over vast geographical distances. Ironically, this results in the effect that geographical distances might develop into something more virtual, and virtual or mediated relationships might become something more real. Maintaining a family under transnational conditions, however, takes much more than a smartphone and Internet access.

As I have established in this chapter, being a virtually-present-while-physically-absent parent necessitates a cooperative family system, which, with the help of technology, enables the absent parent to be there with his or her family and to assume responsibilities for care. Presence, to put it in Christian Licoppe’s words, is nothing physically given or taken by migration; rather, it is “something to be worked on and is based on skills, as well as dispositions, mechanisms, resources and constraints” (Licoppe 2015, 97). In a severely unequally globalized and mediatized world, the ability to acquire resources, develop skills, and learn to manage dispositions and constraints in order to expand the reach of one’s presence turns out to be essential when striving for a decent social position in global society.

References

Adams, Richard H., and John Page. “Do International Migration and Remittances Reduce Poverty in Developing Countries?” World Development 33.10 (2005): 1645–1669.

Baldassar, Loretta, and Laura Merla. Transnational Families, Migration and the Circulation of Care: Understanding the Mobility and Absence in Family Life. New York: Routledge, 2013.

Bareiro, Line. “Paraguay empobrecido: Análisis de coyuntura política 2004.” Derechos Humanos en Paraguay 2004. Ed. CODEHUPY. Asunción: Editora Litocolor, 2004. 13–28.

Basch, Linda, Nina Glick Schiller, and Cristina Szanton Blanc, eds. Nations Unbound: Transnational Projects, Postcolonial Predicaments and Deterritorialized Nation-States. Amsterdam: Gordon and Breach, 1994.

Brock, Gillian, and Michael Blake. “Global Justice and the Brain Drain.” Ethics & Global Politics 9.1 (2016) <http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/egp.v9.33498> [accessed: 14 March 2018].

Bryceson, Deborah Fahy, and Ulla Vuorela. The Transnational Family: New European Frontiers and Global Networks. New York: Berg, 2002.

Clementi, Hebe. La frontera en America. Una clave interpretativa de la historia americana 1. Buenos Aires: Leviatan, 1987.

Epskamp, Heinz. “Integration.” Lexikon zur Soziologie. Eds. Werner Fuchs-Heinritz et al. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 2007. 301.

Faist, Thomas, and Christian Ulbricht. “Von Integration zu Teilhabe? Anmerkungen zum Verhältnis von Vergemeinschaftung und Vergesellschaftung.” Sociologia Internationalis 52.1 (2014): 119–147.

Fresnoza-Flot, Asunción. “Migration Status and Transnational Mothering: The Case of Filipino Migrants in France.” global networks 9.2 (2009): 252–270.

Gómez, Pablo Sebastián, and Eduardo Bologna. “Pobreza y remesas internacionales Sur-Sur en Paraguay.” Revista Brasileira de Estudos de População 31.2 (2014): 431–451. <http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbepop/v31n2/a10v31n2.pdf> [accessed: 14 March 2018].

Gregorio Gil, Carmen. Migración femenina. Su impacto en las relaciones de género. Madrid: Narcea Ediciones, 1998.

Greschke, Heike. Is There a Home in Cyberspace? The Internet in Migrants’ Everyday Life and the Emergence of Global Communities. New York/London: Routledge, 2012.

Greschke, Heike, Diana Dreßler, and Konrad Hierasimowicz. “Die Mediatisierung von Eltern-Kind-Beziehungen im Kontext grenzüberschreitender Migration.” Mediatisierung als Metaprozess. Eds. Friedrich Krotz, Cathrin Despotović, and Merle-Marie Kruse. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 2017. 59–80.

Greschke, Heike, Diana Dreßler, and Konrad Hierasimowicz. “Im Leben kannst Du nicht alles haben – Soziale Ungleichheit im digitalen Zeitalter. Elternschaft auf Distanz in teilweise migrierten Familien.” Mediatisierte Gesellschaften. Medienkommunikation und Sozialwelten im Wandel. Eds. Andreas Kalina, Friedrich Krotz, Matthias Rath, and Caroline Roth-Ebner, 2018 (in print).

Guereña, Arantxa. The Soy Mirage: The Limits of Corporate Social Responsibility – the Case of the Company Desarollo Agrícola del Paraguay. Oxfam Research Reports August 2013. <https://d1tn3vj7xz9fdh.cloudfront.net/s3fs-public/file_attachments/rr-soy-mirage-corporate-social-responsibility-paraguay-290813-en_2.pdf> [accessed: 14 March 2018].

Hobbs, Jeremy. “Paraguay’s Destructive Soy Boom.” New York Times 2 July 2012 <http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/03/opinion/paraguays-destructive-soy-boom.html> [accessed: 14 March 2018].

Kaneff, Deema, and Frances Pine. “Emerging Inequalities in Europe: Poverty and Transnational Migration.” Global Connections and Emerging Inequalities in Europe: Perspectives on Poverty and Transnational Migration. Eds. Deema Kaneff and Frances Pine. London: Anthem Press, 2011. 1–37.

Kofman, Eleonore. “Stratifikation und aktuelle Migrationsbewegungen.” Transnationalisierung sozialer Ungleichheit. Eds. Anja Weiß and Peter A. Berger. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 2008. 107–135.

Koopmans, Ruud. Assimilation oder Multikulturalismus? Bedingungen gelungener Integration. Berlin: LIT Verlag, 2017.

Koschorke, Albrecht. “Ordnungen der Vielfalt. Integration.” Das neue Deutschland. Von Migration und Vielfalt; anlässlich der Ausstellung Das Neue Deutschland. Von Migration und Vielfalt. Eds. Özkan Ezli and Gisela Staupe. Konstanz: Konstanz University Press, 2014. 220–223.

Krotz, Friedrich. Mediatisierung. Fallstudie zum Wandel von Kommunikation. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 2007.

Licoppe, Christian. “Connected Presence: The Emergence of a New Repertoire for Managing Social Relationships in a Changing Communication Technoscape.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 22 (2004): 135–156.

Licoppe, Christian. “Contested Norms of Presence.” Präsenzen 2.0, Medienkulturen im digitalen Zeitalter. Eds. Kornelia Hahn and Martin Stempfhuber. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 2015. 97–112.

Parreñas, Rhacel Salazar. Servants of Globalization: Women, Migration and Domestic Work. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001.

Pries, Ludger. “‘Transmigranten’ als ein Typ von Arbeitswanderern in pluri-lokalen sozialen Räumen. Das Beispiel der Arbeitswanderungen zwischen Puebla/Mexiko und New York.” Soziale Welt 49 (1998): 135–150.

Scheller, Friedrich. Gelegenheitsstrukturen, Kontakte, Arbeitsmarktintegration. Ethnospezifische Netzwerke und der Erfolg von Migranten am Arbeitsmarkt. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 2015.

Smith, Anthony D. The Antiquity of Nations. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2004.

Smith, Robert. “Transnational Localities: Community, Technology and the Politics of Membership within the Context of Mexico and US Migration.” Transnationalism from Below. Eds. Michael P. Smith and Luis E. Guarnizo. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1998. 196–240.

Vertovec, Steven. “Cheap Calls: The Social Glue of Migrant Transnationalism.” Global Networks 4.2 (2004): 219–224.

Wimmer, Andreas, and Nina Glick Schiller. “Methodological Nationalism and Beyond: Nation-State Building, Migration and the Social Sciences.” Global Networks 2.4 (2002): 301–334.

World Bank Group. Migration and Remittances Factbook 2016. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2016. © World Bank. <https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/23743> License: CC BY 3.0 IGO.