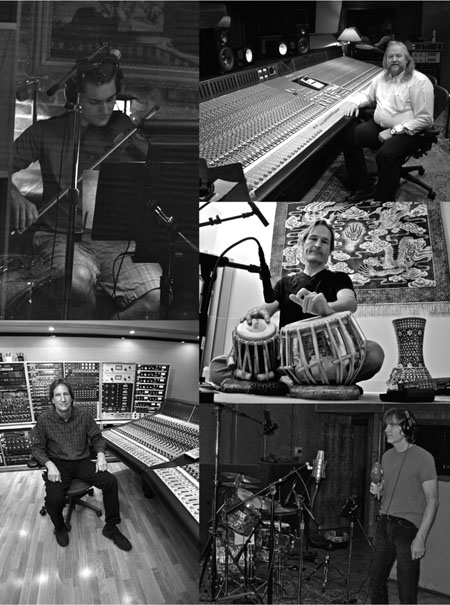

Left column top to bottom: Andy Leftwich at House of David Studio (photo by Kate Hearne) / Allen Sides at Ocean Way Recording (photo courtesy of Ocean Way Recording). Right column top to bottom: Mark Evans (photo courtesy of Mark Evans) / Kirby Shelstad (photo by Rick Clark) / Big Star’s Jody Stephens (photo courtesy of Ardent Recording, John Fry).

Mastering is the final refinement that helps give a finished recording the best sound it can have. A good mastering job can make a well-engineered recording sound perfect on the radio and audiophile systems. Listen to Dire Straits, Steely Dan, Sting, U2, or any number of classic releases to underscore that point. Mastering can also help restore and present very old recordings in their best light. That said, some “remastered” classics have been ruined by over-limiting originally dynamic classics…but that’s another story. For this chapter, I’ve invited Bob Ludwig, Andrew Mendelson, Greg Calbi, Gavin Lurssen, and Jim DeMain to offer their insights into mastering, from technical issues to interpersonal client perspectives.

Credits include: Radiohead, Madonna, Bruce Springsteen, Guided by Voices, Paul McCartney, Rush, Pearl Jam, Nine Inch Nails, U2, Bee Gees, Dire Straits, Jimi Hendrix, Nirvana, AC/DC, Bonnie Raitt. See the Appendix for Bob Ludwig’s full bio.

Mastering is the final creative step in the record-making chain. The purpose of mastering is to maximize the inherent musicality on a given master recording, be it analog tape, Direct Stream Digital, hard drives, DVD-ROMs, or a digital download. The recording and usually the mix engineers have struggled to get their part of the recording as good as it can be, and a good mastering engineer has to have the knowledge and insight to know whether preparing the recording for the pressing plant and iTunes requires doing a lot, very little, or even nothing creatively to the master.

I have often said it is difficult to give awards to mastering people for a particular project, as no one but the artist and producer usually knows exactly how much improvement came from the creative input of the mastering engineer. I worked on an Elvis Costello master engineered by Geofrrey Emerick [one of the engineers on Beatles recordings] that was so good all I could do was get out of its way and let it just be itself. On the other hand, I once mastered a recording that needed so much help, literally 20 dB of level changes during the course of the album and lots of equalization and judicious use of compression. This particular recording won a Grammy for its engineer for Best Engineered Record - Non-Classical…not even a thank you for me! So even having the best job in the world does have its peaks and valleys.

Only a few years ago, recording and mix engineers all tried to make the very best-sounding mixes they possibly could. This culminated in making audiophile analog or high-resolution digital surround sound recordings. We were finally leaving the quality of the compact disc behind and ascending to new audio quality heights. Then the iPod and iTunes were introduced to the world a month after 9/11.

Sony’s invention of the Walkman cassette player and MDR-3 headphones broke ground in 1979. In 15 years, Sony sold 150,000,000 players. This allowed people to hear a cassette of a Mahler symphony and get emotional goose bumps while hiking on top of a mountain. The cassette contained the equivalent of a single vinyl LP.

In less than seven years, between October 2001 and September 2008, Apple sold 173,000,000 iPods, the most successful audio player ever. The single 80-GB iPod, smaller than the Sony Walkman with better quality, could hold the equivalent of an entire record collection, a stack of vinyl records over 16 feet tall. This revolution of convenience over quality quickly took hold. The quest for high-resolution audio and, for me, the extra musical emotion that a system like that can yield went quietly away. Now the average consumer sound quality was less than a compact disc. We now hold the compact disc as the gold standard of sound quality because everything else has fallen beneath it. This is a shame.

Partially due to the instant A-B comparisons everyone now makes on their iTunes software and with disparate sources fighting to be heard next to each other on the iPod Shuffle, many producers and artists have been pushing harder and harder to have their recordings be as loud as or louder than other recordings. If it isn’t already as loud as a commercial CD, some A&R people will reject an otherwise perfectly musical mix submitted from a great engineer. It is as if the mastering process is being ignored. People decided they no longer wanted to turn their volume knob clockwise to enjoy a dynamic mix with a low average level. Now many world-class remix engineers will mix a recording and do the musically suicidal act of compressing it to death before sending it to the mastering stage. This insanity comes out of paranoia that non-loud mixes will be rejected in the marketplace, and the world-class engineer might find himself not working as much. Most of the world-class mixers do not fall into this trap, but there are actually so few truly excellent mixers that if even one of them succumbs to this pressure, it turns the fun part of my job into an annoyance, as I have to figure out what to do with what they have given me. I have nothing against a loud CD that makes sense musically. It is just that every CD is different, and some benefit from loudness, and most benefit from dynamics.

In the days of vinyl disk cutting, there were a handful of really great disk cutters who were also creative sound mastering engineers. When the CD was invented, some people asked me, “What will you do now that there is no more mastering?” They did not understand the finesse and importance of the mastering stage that had nothing to do with making a good cut. Now there are thousands of people who call themselves mastering engineers who convince clients they are audio artists. Most of them only know how to do one thing well—how to turn a limiter knob clockwise until the music is squished as loudly as a commercial CD.

Mastering is the last chance to make something sonically better. The first rule of mastering is like the doctor’s “first, do no harm” credo. There is nothing worse than a mastering engineer doing something to a mix that doesn’t need anything just to earn his fee. An ethical engineer will tell a client if they have submitted a perfect recording. Fortunately for the mastering profession, even with excellent mixes one can usually make a valid musical contribution that will in fact make it sound better. A well-honed mix may need only a small amount of correction to really make it shine. Some artists, like the Indigo Girls or the late Frank Zappa, are so in tune with their music that they can accurately perceive the smallest EQ change, something that would escape even most musicians. These subtle changes mean a lot to them.

So there is much more to mastering than making something loud—it is finding the sweet spot between something that sounds impressively loud and something that sounds impressively dynamic. The engineer often contributes to determining the spacing between the songs and the rebalance of the internal levels of each song, adding or subtracting equalization as each song requires. In short, the engineer wants to make a great-sounding record that a consumer can put on and not feel the need to change their playback level or adjust their tone controls while listening.

When mixing a recording, it is wise to make the best balanced mix you can and then supply an additional mix with the vocal track raised perhaps 1/2 dB and even another one with the vocal raised a full dB. This can make life much easier if an A&R person decides that your vocal level wasn’t quite loud enough. In addition, if there is an issue with the vocal after mixing, one can edit from a vocal upmix to fix a word or phrase that wasn’t quite intelligible. Sometimes, an engineer will supply us with a vocal stem as well as the TV track, which is the rest of the music minus the lead vocal. This allows the mastering engineer to rebalance the mix himself. This would seem ideal, but most mastering engineers do not want to get into the mixing business. Mixing a record is a very different “head” from mastering a record, and it can be difficult to stop a mastering session, go into “mix mode” with the stems, and then try to get refocused into mastering again.

For the approximately 90 years between the invention of the phonograph record and the invention of the compact cassette, disk cutting was the only medium one needed to deal with while mastering. The quality of the cassette became suitable for music reproduction and eventually outsold the vinyl LP due to portability at the expense of quality. The cassette was, 95 percent of the time, mastered exactly as the vinyl disk was. In fact, it was made from the identical cutting masters created for international vinyl cutting. A vinyl disk can cut 15,000 Hz at a high level, but only for a few milliseconds; otherwise, the cutter head would heat up from the massive amount of energy it was being fed from the cutter head amplifiers. The cassette tape was simply not capable of recording 15 kHz at a high level, so the overload characteristics of the cassette were different from the LP. Sometimes we would need to make specially done masters for cassette duplication that had the sibilance especially reduced.

When the compact disc was invented, for the first time we could concentrate totally on the musicality of a piece of music and not have to worry about any technical considerations of skipping grooves or the inability of the medium to reproduce high frequencies, et cetera. The Brothers In Arms album I mastered by Dire Straits was one of the first albums mastered with the CD totally in mind. No compromise was made for the vinyl disk cutting process at all. Plus, it was long, to take advantage of the longer playing time of the CD versus vinyl. The original release had an edited, shorter version for the vinyl. It was the “killer app” for the compact disc, and it sold big numbers and was highly regarded.

Of course, when I started mastering, everything was analog; there was no digital. I mastered my first discs that were cut from a digital source in 1978: a Telarc classical disc.

The theory behind digital recording has been around for quite a while. Pulse-code modulation, the system we generally use to record and play back digital music, was patented in 1937. The earliest examples of digital music were created on big computers by feeding it stacks of punchcards and letting the computer crunch the numbers overnight. Most of the results were disappointing, in retrospect. The world was waiting for computers to get fast enough to process the amount of data necessary to record music and play it back in real time. The first digital tape recorder was invented in 1967 but was not suitable for music. In 1976, Tom Stockham and his Soundstream company made some of the first digital recordings that still sound good today. He also invented the ability to sample-accurate edit digital audio on a computer. Some think this qualifies as the first DAW [digital audio workstation]. Then a plethora of non-standard digital machines came into common use. Mastering studios either needed to rent these expensive devices or own some of the more widely used ones. There were no standards at first for the sampling rates of the recordings; only 14- or 16-bit dynamic range was available. Digital recorders included the Sony and JVC recorders operating at 44.1 kHz and 44.056 kHz. The 3M digital machine originally ran at 50 kHz. The Mitsubishi X-80 ran at 50.4 kHz. Then sampling rates became fairly standardized at 44.1 kHz and 48 kHz. When the CD was invented, mastering studios needed to re-outfit themselves with very expensive Sony PCM-1600, then 1610, then 1630 ADC and DAC boxes that recorded on 3/4-inch U-matic tape recorders that were all expensive to buy and to maintain. Expensive digital editors and tape checking devices, as well as machines to author the CD with the proper PQ and ISRC codes, needed to be bought.

Mastering was revolutionized again in 1987, when Sonic Solutions, which came out of the 1985 Lucasfilm DroidWorks project [that also created Pixar], created the first digital audio workstation as we know them today. It did non-linear editing as well as CD creation and NoNoise™ digital de-ticking and de-hissing. This changed everything. As chief engineer of Masterdisk, we bought the first Sonic Solutions on the East Coast. Originally, digital recorders and editors were made to mimic analog tape machines as closely as possible. Early Sony and JVC digital editors mimicked tape machines with their ability to “rock” a virtual tape to locate an edit spot. The Sonic Solutions suddenly transformed digital recording with nonlinear editing, the ability to make sample-accurate edits with one’s eyes as well as one’s ears, and the ability to repair defects in recordings that were otherwise thought to be unfixable.

Mastering then evolved with the invention of digital domain consoles and signal processors that could be used with these new machines. Many outboard boxes were digital devices. The early Sonic Solutions workstations contained digital equalizers and compressors, parts of which were easily surpassed in quality by standalone hardware boxes by Daniel Weiss, Lexicon, and other early pioneer digital manufacturers.

When Pro Tools came on the market in 1991, they quickly grabbed market share from the then-ubiquitous Sonic Solutions by opening their architecture to third-party developers. Sonic stuck to trying to make everything themselves, but Digidesign [makers of Pro Tools] soon had a plethora of different digital plug-ins that sold a lot of machines for them. Sonic still led the way with being the first digital workstation to operate 24-bit with 96 kHz and then 192 kHz, then even Direct Stream Digital 2.8224 MHz, but Pro Tools finally caught up at least with high-resolution PCM. Of course, other digital workstations came on as competitors.

The present state of mastering, due to cheaper memory, hard drives, and blazing multi-processor chips, has finally created a situation where the digital workstation can now have plug-ins that finally start to rival any standalone hardware box. The fact that it is all highly automatable and perfectly repeatable for recalled mixes makes it a highly compelling way to operate. For now, mastering in a hybrid mode of both analog and digital has big advantages. It can allow the mastering engineer to remain in the right—creative side—brain and have a minimum of switching into technical mode by needing to use a mouse to click on a button a few pixels wide, et cetera. But soon digital workstations will have virtual touch-screen interfaces that can look like an analog console or anything one desires. Touching the screen can have exactly the same result as moving actual knobs as one does today. Equalizers will have so much DSP that they will be able to equalize based on harmonic structure of the music being played into them, perhaps even moving with the chord changes—who knows? As prices drop and DSP becomes even more plentiful, the gap between professional and consumer gear will pretty much disappear. Already, anyone who owns a Pro Tools rig considers himself a mastering engineer. It takes years of constant learning to become a really good mastering engineer, a lot of patience and people skills. I feel I am still learning every day, and I’ve been doing this a lot of days!

Credits include: The Rolling Stones, Death Cab for Cutie, Emmylou Harris, Garth Brooks, Mariah Carey, Dixie Chicks, Kings of Leon, Mötley Crüe, Van Morrison, Willie Nelson, Kenny Chesney, Ricky Skaggs. See the Appendix for Andrew Mendelson’s full bio.

Today’s recording industry is rapidly changing, and the role of the mastering engineer is changing with it. The decentralization of the recording business, as well as new techniques and production standards, has made the role of the mastering engineer more difficult to define than it once was.

The first step I take when approaching a new project is to determine the most effective role I can play. Many projects I work on have teams of producers and engineers who have spent countless hours working with the artist, picking apart every detail of the music. Through their efforts, they often come very close to or completely realize their vision. Other projects come from musicians who have done their own recording and feel apprehensive about the results they were able to achieve. These two situations will often require different sets of skills and tools. Additionally, there are many desirable sonic possibilities for any given piece of music. Understanding what is appropriate in a given style and what your client wants, even when they are unable to express it, is a necessary skill set to develop. Accurately determining the role your client wants you to play and the role the source material requires you to play is fundamental to successful results.

The mastering stage is essentially a bridge between the studio world and the consumer world. My primary goal is to make sure the vision of the artist and the producer will translate as intended outside the production world. This is one reason my mastering room at Georgetown Masters is set up to feel like a listening room you can work in, rather than a workroom you can listen in. The room consists of two sides. When facing one side, you have the mastering console in front of you, along with a pair of near-field monitors. When you turn around, you face an audiophile-quality listening chain with nothing between the listener and the speakers—the ultimate environment for listening with minimum sonic and mental distractions. In addition to its sonic benefits, this type of setup promotes a different way of listening from that of a typical studio—one more conducive to someone enjoying a song rather than creating one. I listen in a different way than my recording and mix engineer counterparts. I can listen to songs as entities in and of themselves, never having been intimately involved in their creation. This provides me with an important vantage point to find flaws missed by the tunnel vision that can be created by being too close to a project.

To become a successful mastering engineer, remember that you are collaborating with people, even if you never meet face to face. In my experience, people tend to want to work with somebody they feel they can relate to. Building strong relationships with your clients will lead to not only repeat business, but also more successful sessions. The first thing I do prior to starting a session is to ask the client about their recording philosophies, their desires for dynamic range versus apparent volume, and any other subjective opinions they may have. Although these opinions may change over time or from project to project, working with somebody with whom you have a strong long-term relationship can give you greater insight into their beliefs and may greatly enhance everyone’s ability to achieve their goals.

Mastering is among the most exciting yet misunderstood processes in music production. Mastering is both an art and a science, drawing upon musicality and emotion, technique, and methodology. The creative stage of mastering, in its simplest form, involves taking what are essentially completed songs and then primarily utilizing elaborate but similar controls to those used daily by music listeners on their own playback systems, extracting the full potential of each song’s musicality. The difference is that the tweaks I make are allowed to become a part of the music’s identity, rather than simply a personal playback preference. If my concept of musicality translates and resonates with those who created this music and those for whom this music was created, I am successful in my job. For all intents and purposes, I am a professional music listener—pretty good work if you can get it.

Credits include: Paul Simon, John Lennon, David Bowie, Bruce Springsteen, Norah Jones, Beastie Boys, Bob Dylan, John Mayer, the Ramones, Talking Heads, Patti Smith, Pavement, Dinosaur Jr., Brian Eno. See the Appendix for Greg Calbi’s full bio.

Imagine for a moment that the oil crisis caused a jump in the use of the horse and buggy. That’s the best way I can describe the phenomenon of the vinyl record album’s comeback in our time. The skill I developed mastering LPs for 20 years between 1972 and 1992 is suddenly back in demand, and after mastering thousands of albums, I hope to offer some advice to producers, engineers, and record companies, which these days are often the same person. Because the techniques used to record and mix albums—or sound files, as they are currently known—have morphed into something entirely different since the vinyl era, understanding the complexities of the vinyl LP is essential to making a great-sounding product. The vinyl LP, like the horse and buggy, provides unique pleasures, but it takes a commitment to excellence to make the experience truly worthwhile.

There is no way to assess the correct technique for cutting a master lacquer without an analysis of the technical aspects of the project itself. In their heyday, albums were cut from analog tapes assembled with razorblade and splicing tape on A-side and B-side reels. The assembled mixes passed through analog equalizers and limiters into an amplifier and cutter head, and then they were cut into an acetate. Today, the vast majority of projects begin as digital files of various word lengths and get mastered for CD duplication. These Red Book 16-bit/44.1 files, in turn, frequently get converted to compressed digital files as they are purchased and stored by consumers. The most commonly asked question by clients today is, “Can I use the CD master to cut the vinyl?” Here’s the not-so-simple answer: “That depends….”

As with any product, the manufacturer needs to determine what he is selling and to which market he is selling. You don’t see Rolex displays in college bookstores, nor does Tiffany carry hoodies. The most important technical question that needs addressing is, “Is the LP simply a transfer of the sound of the CD on a different medium, or does it stand alone as a translation of the mixes into the vinyl form?” The simple transfer of the CD can be accomplished at a much lower cost, as the mastering cost has already been absorbed in the CD budget. However, if the desire of the producer is to make maximum use of the sonic potential of the LP, additional steps need to be taken at a not insignificant cost—one that could boost the sales price of the LP or cut into its profit potential. To complicate matters further, the LP now exists in the music world as a special product. Many artists are using them as loss leaders to reach a niche market, one that in many cases includes bloggers who eagerly respond to the great sonics of the LP—an anti-MP3 of sorts. These factors will all determine how the LP mastering should be accomplished.

Let’s begin by outlining some of the factors in turning digitally mixed albums into LPs. At present, this would include more than 90 percent of the albums we master at Sterling Sound.

Have the mastered levels of the CD compromised the intended dynamics, or are they an essential part of the sound of the production? Has competing in the level wars diminished the impact of the mixes? This is a key question, and had the dynamics been compromised, it would require a separate mastering for making the best-sounding LP. The mastering engineer and the producer should discuss this prior to the mastering, as generating a separate digital LP master would take much more time when done at a later date.

Can the LP master be generated as a high-definition file (88.2 to 96K) during the CD mastering, considering the techniques of the mastering engineer? Again, this could add to the amount of time used and can add a bit to the budget. At Sterling Sound, our cutting room has a high-resolution digital-to-analog converter (DAC), which can significantly improve the sound of the LP.

Huge amounts of low end will eat up space on an LP, sometimes causing the level of the LP to be lowered significantly. If so, an analysis needs to be done with the engineer in relation to the total length of the sides of the LP. More than 21 minutes of music could result in a decision to cut some of the ultra low end, again requiring a separate LP master to be generated. Of course, this decision could be made by the eventual LP cutting engineer, with a much less degree of control by the producer.

Brittle, intense highs will overload a cutter head causing distortion and put greater demands on LP playback systems, which are often misaligned. Again, problematic top end can be filtered by the cutting engineer, but greater control of highs can be accomplished by generating a separate LP master during the CD mastering stage.

A cutter head does not do well with ultra-wide stereo information. It causes extreme vertical movement in the head, resulting in light or actually missing groove depth. This causes skipping and will either be rejected by the pressing plant or undiscovered by both the plant and the cutting engineer, causing buyers to return their LPs because they skip.

A separate cutting master can be generated using mix narrowing in the workstation to allow for a safe cut. This is sometimes impossible to do at a later time by the cutting engineer.

Most of these problems can be solved by the cutting engineer simply lowering the level of the cut, but as the cut gets lower in level, the surface noise becomes a major factor, and the LP can lose its immediacy. Furthermore, for some reason, louder grooves just sound better. There is some physical element in disc playback that seems to fatten and widen with the louder cuts. There were always level wars for LPs in the ’70s, but they resulted in better-sounding product, not worse-sounding as in the CD era.

As you can see, it is important to control costs and expedite the process to determine in advance whether the project will be released on LP. Unfortunately, until now, this has not been the case, and many times the client will grudgingly agree to use the CD master to make the LPs. Again, I repeat that this is not always undesirable, but in many cases is not the best way to make a great LP.

To analog purists, vinyl records cut direct from analog tape represent the highest evolution of music playback. However, for those not experienced with this workflow, there are a number of factors to consider.

When cutting from analog masters, the engineer uses a specially configured “preview” tape machine with two sets of playback heads and two sets of output electronics. On playback, the tape first passes over the preview head, which feeds the disc-cutting computer. Then, after going over an additional roller that creates a delay, the tape passes over the audio head, which feeds the cutter head.

The songs need to be assembled on reels. This is impossible if the mixes were done at different speeds or with different alignment, as was a constant problem in the LP era. However, in those years many projects were done with one producer and in one studio; this is frequently not the case now. Any of the mixes done digitally would have to be copied to analog tape and inserted.

Crossfades are extremely time consuming in the analog domain. Three analog machines are needed, with two sets of faders and an extremely patient and deep-pocketed client. Any album that relies on crossfades to have the right mood would need to be budgeted accordingly.

If an excessive amount of EQ and limiting needed to be done to the mixes, and the songs needed a very different mastering approach from song to song, the mastering engineer would be limited as to just how much he could process them, as AAA cutting requires changes to be done on the fly between songs.

I would add that very few projects recorded and mixed in this era would qualify for an AAA cut, and that decision should always be discussed with the mastering engineer. Generating a high-definition digital master would be an effective alternative.

In conclusion, I must stress that producing a great-sounding LP will require a financial and artistic commitment, but one that would have tremendous rewards for the vinyl lover. An experienced cutting engineer with a quality DAC, lathe, and cutter head can make a fine vinyl cut from a 16-bit/44.1 CD master. The additional steps I have outlined here can further enhance the cut and expand the market for the LP. Next time you rifle through a bin of old LPs at the local antique center, realize that albums you see were recorded in professional studios with budgets 8 to 10 times higher in real dollars than the average budget today and were transferred to vinyl with no digital conversions whatsoever from original master tapes. They were probably recorded by professional engineers who spent years as studio assistants, and the only way to listen to them on demand was to buy them or have friends who did. If you see one by an artist you like, and it’s less than 10 bucks, I would recommend you buy it and a turntable to play it back. The sound might surprise or even shock you.

Credits include: Elvis Costello, Tom Waits, Quincy Jones, James Taylor, Alison Krauss and Robert Plant, Leo Kottke, Social Distortion, Guns n’ Roses, Rob Zombie, Lucinda Williams, Queen Latifah, Diana Krall. See the Appendix for Gavin Lurssen’s full bio.

Listening to music is an intensely subjective experience. We all hear things a little differently, depending on the frequency range within which we function. What may be too bright or too loud for me may be just right for you. Experienced audio engineers can—and should—give advice, but the final sound that really counts is the sound that the artist wants. It is essential for all of us in the recording industry to understand that fact so that we can give our clients the best product possible, the one that really captures their vision and opens a connection between the artist and the fans using current-day formats of audio storage. The best way to achieve that goal is by clear communication. I have learned over the years that one of the first important steps for me as a mastering engineer is to communicate with a client at a human level and to leave the technical stuff until later.

Communication with artists and producers—even with fellow mastering engineers—can be quite an art inside a mastering studio. And, of course, it is an art outside the studios in media such as the trade press. I have written a number of articles, and one of the best received was about the use of compression. I tried to relate the subject to everyday human experience, and I found to my pleasure that people seemed to like that approach.

At Lurssen Mastering, our first objective is to sift through the spoken and body language to decipher precisely what is wanted and to help the client reach a point of understanding of what is technically desirable and possible. Unless the engineer observes and listens carefully, it can be quite easy to understand something differently than the way it was intended. This is one of the reasons why regular clients are so valued. We get a feel for what people want, and they know what we can provide. There is a comfort level based on experience and achieved results. But a comfort level can be quickly established with first-time clients too, based on a clear level of communication. Once that level has been found and a good back-and-forth rapport established, we can get down to work.

I work within a frequency spectrum. I mix with frequencies, and I do it using analog equipment. I use equalizers, compressors, limiters, analog-to-digital converters, digital-to-analog converters, and carefully planned gain structure in the interaction of all the equipment to accomplish all of this. There are either customized or stock line-level amplifiers in every step of the stage and of particular importance on the front end of an analog-to-digital converter and on the back end of a digital-to-analog converter. It is crucial that the gain structure of what is feeding the A-to-D or what the D-to-A is feeding is properly integrated in the chain of events. Only with very careful attention paid to the gain structure of all these devices working in concert can we achieve a fully professional sound—this along with two decades of training and sensibilities learned on the job and during my time at Berklee College of Music.

Sometimes I open up stem mixes and do the blends in the mastering studio, which is a step closer to the mixing process. As studio environments have been set up in compromised environments, clients rely on me more and more to open stem mixes and work from them. Stem mixes are a two-channel blend of drums or guitars or vocals or whatever else can be imagined, blended into two tracks so that two tracks of drums and two tracks of guitars and two tracks of vocals can all be further blended and mixed. This process can open another can of worms because a summing bus amplifier needs to be used in order to properly integrate the blend of frequencies into the rest of the signal chain.

Everything involved in the interaction between a mastering engineer and the client, which can consist of the artist, the engineer, the producer, the manager, and the A&R person, is like mastering a record itself. We are paying attention to a lot of detailed aspects, which include communication both ways, the use of equipment and the way it all interacts along the signal chain, and the way songs sound using our sensibilities in these areas to create one big, successful picture. A happy artist and a good sounding product….

And it is all done for the fans.

Credits include: John Hiatt, Lambchop, Vince Gill, Kris Kristofferson, Nanci Griffith, Michael McDonald, Jimmy Buffett, Albert Lee, Marty Stuart, Steve Earle, the Iguanas, Billy Joe Shaver, Jill Sobule, Shazam. See the Appendix for Jim DeMain’s full bio.

Part of the mastering engineer’s job description is creative problem-solving. The following are several issues that seem to crop up regularly.

One of the biggest issues I have concerns having to address over-compressed mixes. I’m sure I’m not the only mastering engineer to have this problem. If I get something that’s way over-limited, it’s really hard to achieve satisfying results. No matter how much you do, it will never be as good as if the mix was right in the first place. I’ve found the easiest way to address this is to request a non-limited version of the mix. A lot of my clients do this for me. That way, I really have control over the final compression/limiting.

It’s strange to me that, with the extended dynamic rage that the virtually bottomless noise floor of digital has afforded us, we have gone completely in the other direction to make everything as loud as possible. It’s truly unfortunate that more artists don’t take advantage of that extended dynamic range, instead of being part of this constant push to make louder and louder over-limited CDs. I believe we are really doing a disservice to the recorded music during this time period by the destructive properties of over-limiting. It doesn’t just destroy the dynamics; it also really skews the harmonic overtones of the instruments. So not only do we lose the natural rhythm, but it all starts to sound like white noise. There really is a difference in the way music that has not been over-limited fills the room. It’s much more interactive. Could this trend of over-limiting possibly be a reflection of the increasing noise in the world around us?

Another issue many mastering engineers encounter concerns receiving poorly or non-labeled projects. I can’t stress this enough: Label everything clearly and date it! You may think you’ll remember what was on such-and-such disc, but in two weeks’ time, chances are you won’t. It sounds crazy, but I sometimes have received projects in the mail or FedEx packages containing only a silver disc with no label, notes, and even sometimes no name.

One last problem I regularly encounter is tracks with lots of tiny pops and clicks as a result of not setting an edit crossfade during vocal comping. They’re almost always either right before or right after a vocal line. Please make sure you’ve really addressed this in the mix before you send it to mastering. It’s no big deal to fix these things, but it can be very time consuming.

When I work, I sometimes do everything in real time through all the outboard gear; other times I work “in the box”; and then there are those times when I’ll do a combination of both. It really is all about the project. I usually spend the first hour or so just trying out several different signal paths. I’ll try analog only, digital only, combinations, et cetera, to see what flatters the mixes the best. I can usually tell pretty quickly what will work. Sometimes, just the combination and sequence of the gear can make a big difference before you even start turning any knobs.

Obviously, having an accurate, reliable monitoring setup is the most important thing you can have as a mastering engineer. You can have all the latest bells and whistles in compressors and EQs, but if you can’t hear what’s really happening in the recording before you, then all that other stuff doesn’t really matter. Ultimately, you’re making final decisions on people’s work they’ve spent hours and hours working on up to this point.

Concerning my work methodology, I’m not a guy who’s like, “It has to be all analog through a console!” Now, there’s no argument that a good mix done through a console sounds phenomenal. The front-to-back depth and the height and width of a mix through a console is still pretty hard to beat in the box. But I have heard really good recording and mixing that was done all in the box. I think it really comes down to the people who are doing the recording, using their ears.

Ultimately, your ears are the most important piece of gear you own, and learning to truly listen is the most important thing you can do. It is a disservice to say, “When we do things a certain way, through this or that piece of gear with this method, we always produce great results.” You have to be constantly listening. I sometimes think that with all of computer monitors in front of us, maybe we are looking at the music a little more than we’re listening to it.

I don’t really have a lot to complain about concerning my line of work. After all, I could be carrying bricks up a ladder for a living. That said, I do have a couple of observations about trends in the recording industry that concern me. One is I feel like we may be compromising art in pursuit of convenience. Art shouldn’t necessarily be easy. You shouldn’t just push a button and get art. But I think with the convenience of digital workstations, we are on our way to servicing that delusion. I just hope we can keep things in perspective. Having all these great tools can really be a double-edged sword. I’m not sure that it’s such a great thing that we have the ready facility to make somebody who can’t sing sound like they can sing, or somebody who can’t play an instrument sound like they can play. Fortunately, that sort of stuff usually works itself out in the long run. But, on the other hand, I’m bothered more when I encounter talented artists who actually can play or sing having recordings where every fluctuation in the performance is perfectly straightened out on a grid and every note auto-tuned. Let’s be careful not to trade personality for convenience.