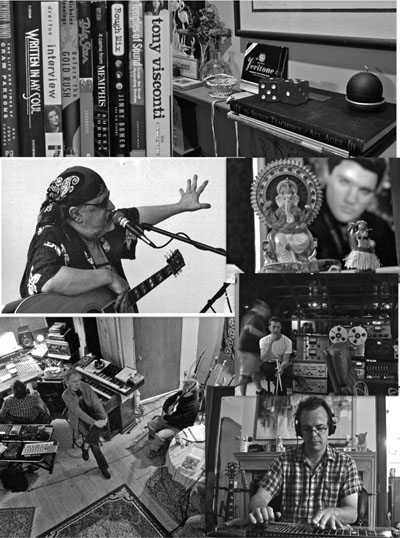

Left column top to bottom: Inspirational music books (photo by Rick Clark) / Jim Dickinson (photo courtesy of Mary Lindsay Dickinson) / Marty Stuart’s American Odyssey, XM/Sirius Satellite Radio at Eastwood Studios (left to right) Eric Fritsch (owner, chief engineer), Rick Clark (producer), Marty Stuart (chief visualizer) (photo by Tzuriel Fenigshtein). Right column top to bottom: 5.1 and The Secret Teachings of All Ages (photo by Rick Clark) / Studio charms at Jim Scott’s PLYRZ Studios (photo by Jimmy Stratton) / Calexico’s John Convertino - Los Super 7 sessions (photo by Rick Clark) / Calexico’s Paul Niehaus - Los Super 7 sessions (photo by Rick Clark).

There is nothing quite like the sound of a great string section or orchestra. A magic performance of a great symphony, concerto, or chamber piece is arguably every bit as powerful as any inspired rock, R&B, or jazz performance. Since the advent of popular recorded music, orchestras and string sections have been appropriated to elevate the emotional delivery of a recording or live performance. In some cases, the integration of symphonic or chamber elements to a band track have been nothing more than sweetening. In other cases, such as the Beatles’ “A Day in the Life,” it has been an essential part of the composition’s integrity.

For this chapter, I talked to experts who have recorded orchestras and chamber groups for serious classical music projects, as well as those who have primarily worked within the popular music contexts. I’ve given them some space to share some important ideas on how to do it right. I would like to thank Milan Bogdan, Richard Dodd, Ellen Fitton, Bud Graham, Mark Evans, and Tony Visconti for their generous gift of time and insight for this subject.

Credits: Tom Petty, Dixie Chicks, Wilco, Boz Scaggs, George Harrison, Traveling Wilburys, Roy Orbison, Clannad, Francis Dunnery, Sheryl Crow, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Green Day. See the Appendix for Richard Dodd’s full bio.

There are so many factors, other than the technical side, that make for a good string sound or recording. To focus on the method of recording strings and just to talk about microphones and that sort of stuff would be very remiss. If there’s an art for me, it’s in encouraging the people to be at their best, which gives me an opportunity to be at mine. That’s the only art involved, really. The rest of it is a series of choices, very few of them wrong. The microphone is almost irrelevant. In fact, if mics were invisible, it would be the best thing in the world.

Nevertheless, if you have a pretty good quality microphone, used in a pretty conventional, orthodox manner, it is hard to mess things up if all the other factors are right. Sometimes people can drop into a session while you are recording a big 60-piece orchestra, and it will sound amazing, and they think you are great; but truthfully, it is sometimes easier to record an orchestra than to record a solo guitar and voice. It really is.

You have 30-odd string players out there, and it doesn’t matter if three of them don’t play at their peak all of the time. The spectacle and what they produce can be quite amazing.

It really comes down to the caliber of musician—I can’t emphasize that enough— and that musician having something worth playing, and the person next to him doing his job, too. If they respect the leader and the arranger, and they don’t mind the music—it’s very rare they are going to like it in a pop commercial world—then you’re onto a good thing. Give them some fun and compliment them. Everybody likes that. After all, they’re human, and there are a lot of them in an orchestra.

Here’s one little tip to make things better. I used to go around the studio—especially in the summer in England, when it was dry—and spray the room with a spray gun (the kind used for plants) before the musicians would arrive. I would go around and soak the cloth walls, and the humidity would gradually leak into the room. It just made things better. I found that I preferred the sound of a wet, humid environment to a dry environment. I think it makes the sound more sonorous. I observed that when it was raining, it sounded better than when it wasn’t. Not having air conditioning helped the sound—but not the players—because it wasn’t de-humidifying.

I also think it adds more of a psychological effect than anything. If you see someone taking care, it tends to impress you. There is a comfort factor as well. If someone isn’t comfortable, then he isn’t going to play well, so imposing the humidity was a good thing. It made people think that you cared and in turn would give you an edge.

You know, you can have the best players in the world, but if they don’t like the arranger, the engineer, the studio, or the person sitting next to them, they are not going to play their best. Even though they might try, it just won’t happen. Yet, if they have a smile on their face, it comes through. You should try to make them comfortable, and try not to take advantage of them, and treat them with respect. It’s the best thing you can do. They deserve your respect, because they have trained very hard to be where they are. If you do that, you can have some great days with them.

There are numerous recording strings tips, in terms of indoctrination, that I could share. My first session around string players happened when I had been assisting maybe about two weeks. Unbeknownst to me, the engineer had arranged for the lead violinist to teach me a lesson that I wouldn’t forget. He told me that I must walk carefully when I walked around the players and the instruments. Make my presence felt. Speak firmly and clearly so people would know I was there. And don’t creep up on anyone, because some of the instruments they are holding are worth thousands and thousands of dollars. You don’t want to have an accident. So the engineer set me up to adjust a mic on the first fiddle, at the leader’s desk, and I had done everything he had told me to do. As I stepped back to make my final tweak on the microphone, he slipped an empty wooden matchbox under my foot. The sound of crushing wood under your foot is something you never forget. [Laughs] It was very clever and a good education. You can tell people all you like about being careful, but there is nothing like that adrenaline rush of “Oh my God, there went my career before it’s even started.” You remember things like that.

Credits: Wynton Marsalis, Firehouse, Dionne Warwick, Bee Gees, Chaka Khan, Jessye Norman, Yo-Yo Ma, Kathleen Battle, Chicago Symphony, Philadelphia Orchestra, New York Philharmonic. See the Appendix for Ellen Fitton’s full bio.

Classic music is all editing. It involves hundreds of takes and hundreds of splices. That’s how classical records get made. You usually are talking about maybe 200 takes for the average record, but we did 15 Christmas songs for a Kathleen Battle record, and there were 2,000 takes. When I say take, it’s not complete start-to-finish recordings of all of the material. It’s little inserts and sections. There might only be several complete takes. Then they record a section at a time or a movement at a time, or there might be a series of bars that they play eight or nine times until they get it right. It’s that sort of thing.

The function of the producer in a classical record is kind of different than in a pop record, because they’re really sitting with the score, listening to each take, and making sure that each bar is covered completely by the end of the session or series of sessions. They have to make sure they have all the right notes that they need, and then they have to come up with an edit plan to put it all together. There’s no drum machine or sequencers. So that’s how classical gets it right.

The producer has to keep track of tempo, pitch, and how loudly or softly the orchestra played each section. The producer also has to know that if the orchestra plays the piece with a different intensity, then the hall reacts differently. When that happens, the takes don’t match.

It is important to familiarize oneself with the piece of music being recorded, so you will know instrumentation-wise what you have, how much percussion there is, and whether there are any little solo bits by the principals in the orchestra. Then you start laying out microphones. We prepare a whole mic list before we go wherever we’re going. We take specific microphones, specific mic preamps out with us when we go. All of the recording is done on location, in whatever hall we choose, and we take all of our own gear with us. Tape machines, patch bays, consoles— everything gets put in a case and packed up and taken with us.

For the most part, you want a fairly reverberant hall, but you don’t want it so reverberant that it starts to become mush. A good hall should have at least a couple of seconds of reverb time.

Normally what we have is a main pickup, which is usually what we call a tree. It contains three microphones set up in sort of a triangular form, and they are usually just behind the conductor, about 10 feet up in the air. Some are 8 feet, some are 12; it depends on the hall. We use B&K’s 4006s or 4009s because they’re really nice omnis that are really clear and clean. They have a nice high end and give you a good blend.

The goal with classical recording is to try to get it with that main pickup, and the input from all the other mics is just icing on the cake. If you end up in a really bad hall or a hall you don’t know, then you end up using much more of the other mics.

Credits: New York Philharmonic, Philadelphia Orchestra, Boston Philharmonic, Cleveland Symphony. See the Appendix for Bud Graham’s full bio.

My feeling of string miking is quite different than normal pop miking. I like to mike from much more of a distance. It is a question of taste. My feeling is that if everything is miked close, the strings are kind of piercing and sharp. I prefer a mellower string sound, and that is the way I like to do it. It is my style. Again, it is a classical sound, as opposed to a pop sound, where everything is close miked, and people desire a more biting sound.

I like the natural room ambiance, but I am more constrained by a good or bad hall. If you are miking close, and it is not a good hall, you are not really hurt by it. If I am miking at a distance, and it is a bad hall, it is going to sound bad. It has to be a good hall for my type of miking to work. It has to have ambiance, and it has to have a high ceiling.

Some of the great halls—Carnegie, the Princeton University Hall, the Concertgebouw in Holland—are hard to get because they are booked well in advance. You have to book many months in advance to get a good hall.

I favor B&K 4006s for violins to cellos. For bass, tympani, French horns, tuba, and other brass, I like Neumann TLM 170s, which are great mics for darker-sounding instruments. For vocal choruses and harp, I choose Schoeps MK 4s. Neumann KM 140s work well for percussion.

While I’ve done many projects that involved a combination of many close and distant mics, I feel that the proper application of a minimal number—like a couple of omni-directional mics placed out front—can achieve some of the most ideal results.

On occasion, it works very well to work with two microphones, usually placed at 7 or 8 feet behind the conductor with the two microphones placed at 7 or 8 feet apart. Depending on the hall, though, it might be 12 to 15 feet high.

The placement and focusing of the microphones is important. At one time, an engineer said to me, “What difference does it make, because you are using omnidirectional microphones?” I said, “Well yeah, but it may be only omni-directional at certain frequencies.” The focusing is extremely important. It isn’t just something that you put up and aim in the general direction of the orchestra. It has to be properly focused, or you will get too dark of a sound.

In order to focus, I would focus between where the first and second violins meet on the left side. I would try to aim it down so it was kind of cutting the strings in half, between the first and second violins. The one on the right side would be doing the same thing, aimed where the violas and cellos would come together. The leakage from the brass would come in and give it distance and provide a nice depth view. If I aimed too far back, then the strings would get dull, and they would lose their clarity. It may also get more brass than you wanted. By focusing the mics at the strings, with the brass coming in, it gives the recording a lovely depth of field.

I found that when the two mics worked, and you listened to it, you could hear the difference between the first horn and the second and the third, with the first one being slightly left of center. The second one would be left of that, and the third one would be left of the second. It gives a wonderful depth and spread.

I once heard a CD where the horns sounded like they were not playing together at all with the orchestra. It was a recording where all these multiple microphones were used. Every one of them came at a different time factor, so that what actually happened was that it sounded like a badly performing orchestra. Actually, it was because of the lack of clarity that was created by all of this leakage. You were hearing the instruments coming to the picture all at different times. The problem wasn’t the orchestra; it was the miking process.

While many engineers still favor analog for recording, I feel that digital is more than fine and just requires a little rethinking, as it concerns mic placement to achieve that warm sound.

Digital is a cleaner medium than analog, and now that we are using 20-bit, there is a noticeable difference. Analog is like a window that has a little bit of haze on it. When you put it to digital, you clean up that window, and it gets to be a little too crisp and sharp. We then learned that we had to change our techniques a little bit. What we had to do, when we started moving in from analog to digital, was to not mike as close. As a result, the air did some of the softening or mellowing that analog would do.

Credits: David Bowie, Morrissey, T. Rex, the Moody Blues, the Strawbs, Gentle Giant, the Move, Sparks, Thin Lizzy, Caravan, Boomtown Rats, Dexy’s Midnight Runners, U2, Adam Ant. See the Appendix for Tony Visconti’s full bio.

Recording strings is a huge subject. It must be looked at as both a recording technique and a writing technique. I’ve heard a string quintet sound enormous at Lansdowne Studios in London in the late ’60s. I asked Harry, the engineer, how he managed to make them sound so big, and he humbly replied, “It’s in the writing, mate!” That was probably the biggest lesson I’ve ever learned about recording and writing for strings. I’ve also heard big-budget string sections sound small and MIDI-like due to the unimaginative writing of the novice arranger. I also must stay with strings in the pop/rock context because there are certain things that apply here only and not in the classical world, with which I have very little experience.

The violin family is several hundred years old, more powerful descendants of the viol family, which used gut strings and not the more powerful metal strings we’re used to today. The violin family [which includes the viola, cello, and bass] have a rich cluster of overtones that make them sound the way they do, and there are many ways of enhancing these overtones in recording. When used in a pop context, the huge hall and sparse mike technique of the classical world won’t work with the tight precision of a rock track. Especially nowadays, when we are getting fanatical if our MIDI strings are two ticks off center. The reverberation of a huge room is often anti-tightness. Recently, I did some live recording in a large London room with a singer, also playing piano, accompanied by a 40-piece scaled-down symphony orchestra. When I counted in, I had to leave off the number four because the reverberation of my voice leaked onto the first beat of the song. I know—it’s every engineer’s dream to record strings in a huge room, but no matter how huge the room is, artificial reverb is added in the mix anyway. Recording pop or rock is not reality! You could never record a loud rock band and a moderate-size string section in the same room anyway.

Ideally, I like to work with a small section consisting of minimally 12 violins, four violas, three celli, and one double bass. I like them to be in a room that would fit about double that amount of players, with a ceiling no lower than 12 feet. I have worked with the same size ensemble in smaller rooms with great results too, because the reverb is always added in the mix anyway. But the dimensions of the room help round out the lower frequencies of the instruments. I like to close mike to get the sound of the bow on the string. If a string section is playing to a rock track, you must hear that resin! So I will have one mic per two players for violins and violas, always top-quality condenser mics! For the celli and bass, I prefer one mic each, aimed at one f-hole and where the bow touches the strings. Then I place a stereo pair above the entire ensemble to catch the warmth of the ensemble, and I use these mics about 50 percent and the spot mics 50 percent in the mix. If I record a smaller group, I use more or less the same mics. A string quartet gets one mic each, plus the stereo pair for the ensemble sound. If I had a larger section, I’d use one mic per four violins, et cetera. Of course, with lots of mics, a phase check should be carefully made—it’s the same problem as when you are miking a large drum kit.

In a perfect world, I love to record each section on a separate track, dividing the violins into two sections and the ambiance on separate tracks too. Often I have fewer tracks than that, and sometimes only two tracks are left for the entire string section. Then it’s a careful balancing act with more lower strings in the balance than what appears to be normal. When using strings with a rock track, there is a lot of competition in the low end, and the low strings seem to disappear.

I don’t approach strings as something from another, more aesthetic world. If strings are to go over a tough rock track, then they must be recorded tough. I’ve seen many a cool rock engineer intimidated by the sight of a room full of middle-aged players and $30,000,000 worth of Stradivarius. If the track is loud and raucous, then the strings should be recorded likewise. It’s also quite appropriate to record with a fair amount of compression so that the energy matches that of the guitars and bass [also stringed instruments].

Headphones also changed the way strings are recorded. When I first started writing for strings in London, the players refused headphones. I had to wear them and conduct furiously to keep them in time. Often we had to play the backing track in the room through a speaker for them, which would lead to leakage problems. That was sometimes a blessing on the mix, but often not! In the early ’70s, the younger string players knew that their elders were always chronically behind the beat, and so they “invented” the technique of listening to half a headphone—the right ear is listening to the track, and the left ear to the fiddle. Remember, those things don’t have frets!

As for writing, my Cecil Forsythe book on orchestration—my bible—has over 60 pages devoted to the violin alone. I won’t go into this deeply here, but the writing of some classical composers is worth examining when writing for a rock track. Beethoven comes to mind. Because the violin family doesn’t have frets, you must have the minimum of one or three players per part. Otherwise, the tuning will be abominable! It is impossible for two players to play in tune for any length of time. One player can only be in tune with himself. But with three, according to the law of averages, one will be in tune, one will be sharp, and the other one will be flat. This will temper the tuning of the part. With a small section, I don’t write in the very high registers—a few instruments will sound squeaky up there. With very high writing, I almost always have half the violins playing the same part an octave lower.

There are so many ways of playing a violin. For more warmth, they can clip a small lead weight on the bridge, and this is called a mute, or sordino in Italian. This works well against acoustic guitar-based tracks. For pizzicato [plucking the strings with a finger], the volume often drops considerably. This can be addressed two ways. Warn the engineer so that he can push up the faders on pizzicato passages or ask the players to stand up and play, putting them closer to the mics. For col legno, in a concert the players tap the strings with the wood side of the bow; in the studio, a pencil sounds much better. Try col legno sometimes instead of pizzicato— you’ll be surprised.

A final word on professionalism when recording strings: A room full of string players is very, very expensive. Each player is being paid hundreds for three hours of work. You should set up and test all mics and headphones the night before or at least two hours before the session. [String players start arriving an hour before the session time.] You don’t want to be setting up with 20 temperamental musicians underfoot— not to mention the odd violin, which is very easy to step on. With mic stands, allow room for bowing [the right elbow]. Give each two players one mic stand to share. Check for squeaky chairs and replace them! Because you have to get a sound very quickly on such an expensive section, ask every section to play the loudest section of the arrangement several times. In other words, if you are using three mics for six first violins, have each pair of players play separately from the other four. When your mic levels and EQ are achieved [EQ the first mic and match the other two with the same settings], ask them all to play at once to check that the three mics are truly capturing six musicians equally. These are mixed to one track, so get it right, dude! Then do the same with the rest of the players. This should take about 10 minutes tops, and then you can get on with the pleasures of recording 20 highly trained experts!

Credits: Marvin Gaye, KC and the Sunshine Band, Funkadelic, Merle Haggard, Barbara Mandrell. See the Appendix for Milan Bogdan’s full bio.

There is a lot to cutting strings. It isn’t just setting up the microphones. If you want to do it right, it takes a lot of time, and the setup is all-critical. You have to know the room you are in and what its characteristics are. Is it heavy at 400 cycles, and should you turn that down? If so, then you don’t want to put the lower strings in that area of the room, because it will muddy up the whole thing. It is the technique of listening to the whole room and then knowing where to stick the microphones and the instruments in that room.

Sometimes, we will dampen the room down. We might put carpet down on the floor, if it is too live. My preference, however, is for a more live kind of room.

Even though I like a live room, phasing can be more of a problem. You may encounter reflections coming back from a wall that may be almost as loud as the original source signal. You can get an echo effect that causes the strings to lose their presence. That now comes into the microphone technique of where and how far away it is from the instrument.

Omni microphones are always the flattest and the best sounding and more preferable than a cardioid pattern. In some instances, I have to switch to a cardioid pattern to knock out some of the reflections in the back, if they get too loud.

To me, the high-voltage mics always sound better than just the phantom-powered mics. That is why I like the Neumanns—the 47s, 67s, and 87s—and the high-voltage B&K and Schoeps mics with the power supply on the floor. The 4000 Series high-voltage B&Ks, especially for violins, are magnificent. They are mind-boggling. They are probably my favorite for miking the room and miking the strings.

For smaller sections, it obviously is a smaller, more intimate sound right away. Usually, I will mike each instrument by itself and get a closer, more up-front, present kind of sound. I will usually use a couple of B&Ks in the room. I am paying more attention to each individual instrument than I am to the overall room sound. When there is less of a phasing problem, then it is easier to make the whole thing work.

For solo cello, I like to use an Audio-Technica 4041A. I would mike it fairly close, but that would depend on the room and how live it is. I would mike it fairly close to the large part of the body of the instrument, because that mic is so bright.

For bass fiddle, I would use a 47 tube and put it toward the body in front of the instrument, either slightly below or slightly above where the bow is actually touching the strings.

For violin, I usually mike overhead, but here is also certain amount of sound that comes from under the instrument itself. It depends on what you are trying to get. You get a fuller sound underneath. If you are miking from both sides, the producer might say, “I don’t like [the bow side sound]. That is too scratchy.” A lot of times, it isn’t that it is too scratchy. You are just getting too much of the bow. So I just turn that mic down and bring the other one up. All of a sudden, the producer likes it, and I didn’t change the EQ, and I didn’t have to change the mic.

I very seldom EQ strings as I record. There is no way to duplicate that. I would rather put some on later. I am so busy dealing with the mix and the blend and the phasing that I don’t have time to mess with the EQ. That is why I pick good mics and just do it right that way.

The following contribution by Mark Evans pertains to his specific approach to recording the Prague Symphony Orchestra for Kevin Kiner’s score for the George Lucas movie, Star Wars: The Clone Wars. See the Appendix for Mark Evans’s full bio.

I’m a close-mike guy. It’s a little annoying to record an orchestra and not have at least some kind of real control in the mix. I don’t like the sound of an orchestra with the cellos and basses just kind of spread everywhere and when there’s just no focus.

When you hear soundtracks like The Bourne Identity, there is a lot of edge and impact in the orchestral sound. You can’t get that without close miking the instruments. Of course, samples might be employed to get some of that sound, but whenever you can, it is nice when you can get that impact with the real instruments. I will usually put 10 mics on 10 cellos and six mics on the six basses and basically just bus them to a stereo panning array.

For recording Kevin Kiner’s score for George Lucas’ Clone Wars, we used a 100-piece orchestra in Prague. I had 50 mics in, plus a Decca Tree,[*] as well as a set of U 87s as surround mikes set in the middle of the room. I have two sets of custom cardioid mics built by a good friend of mine, Howard Gale of Zentec. I always use them in an ORTF array on the front of the Decca Tree (these are the most important mics in the room) and the U 87s in omni on the left-rights.

I used the Earthworks QTC50 mics as overheads on the violins. They are incredible microphones. There is a certain warmth and silkiness these microphones possess that works out great on the violins. It’s not so much you hear it as you can feel it.

I wound up using KM 84s all the way across the basses and the cellos, and it gave the sound the kind of urgency I was looking for, and it ended up sounding great.

I’ve seen so many guys mike French horns from the front [the bells are facing the other way], or I’ve seen guys mike them really high, from the back. One of the big qualities Kevin Kiner wanted with the French horns on the Clone Wars score was for them to be really in your face. We had eight French horns in the section, and I close miked them from the rear, about 3 feet away. I had two A-B stereo arrays behind them. I used four TLM-103s, which I like to use on the brass. It’s a very good-sounding mic. It’s bright, and it really can stand some high sound pressure. There actually wasn’t much room to mike them from the rear. I was really taking a chance, but I just had to do it. The Studio in Prague had a baffle around the French horns and was just relying on the reflection of the sound, which in the end made the horns sound behind the beat to me. I also miked them from the front with the RØDE X/Y stereo microphone. This is because we used Wagner horns on some of the cues. They are actually played with the bells facing forward. The combination of X/Y microphone and the close mics sounded great on the French horns. It really worked very well.

When you’re miking an orchestra, you don’t really have a chance to say, “Hey, hold it there guys! It’s not working, sorry. We’re gonna have to stop!” [Laughs]

I know Kevin Kiner’s writing really well. I knew what he was going to go for; he wants things to be rocking! We call it “The Rock and Roll Orchestra Sound.”

It’s always a challenge to make the percussion sound as good as a sample library. The sample libraries that are out there now are incredible because they have so much definition. It’s just in your face, and you can’t really do that with a bunch live guys in one room. We had six percussionists in the orchestra; with all those wide-open microphones, it was really hard to get the definition on any of the percussion, but I think I was able to do it. It’s always a challenge when you have everyone playing live in one room.

I usually like to give the soundstage mixers enough stems so they’ll have options and can actually do something with the orchestral elements. Close miking the strings really helps the stems. As a result, they actually had control over the urgency of the strings; although in the case of Clone Wars, not one thing was touched on the orchestral score mix. When I went to hear the playback of the final mix, the mixers told me they wound up not doing anything to my mix. That felt good.

[*] The Decca Tree mike technique employs three usually omni-directional microphones placed in a triangle, with one microphone in front, closer to the sound source. Decca Tree is most popular for orchestral and large string section recordings in large acoustically designed rooms or halls and is commonly used in Hollywood film soundtracks. The advantages of the Decca Tree are similar to the M-S mike technique over AB in the fact that you have the ability to adjust the center microphone, thus adjusting the power and central pull of the sound. AB Stereo Microphone Technique is sometimes criticized for lacking a central pull and being too wide a stereo image when placed close to a sound source. The Decca Tree began as a modified AB, adding the center forward spaced microphone. Original size of the T or Triangle was 2 meters wide and 1.5 meters deep. (Definition courtesy of WikiRecording.)