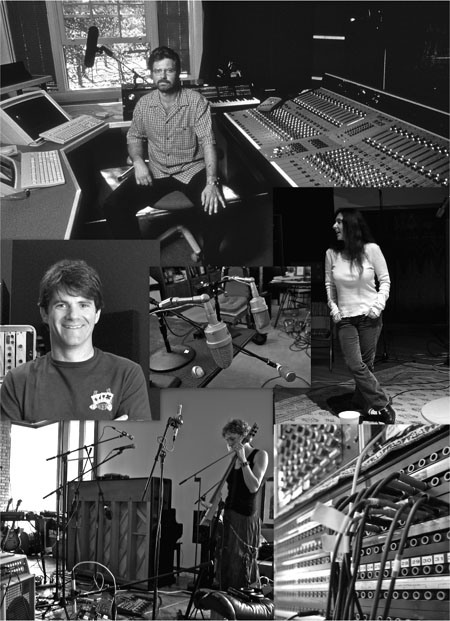

Christopher Boyes, Skywalker Sound (photo by Steve Jennings, Skywalker Sound). Row 2: Jacquire King (photo by Rick Clark) / Neumann M 50s (photo by Rick Clark) / Cookie Marenco (photo by Rick Clark). Row 3: Cregan Montague of Osaka Pearl (photo by Rick Clark) / Plug-ins (photo by Jimmy Stratton).

You’ve worked seemingly endless hours in the studio trying the produce the ultimate single that you think has a real shot to make a splash at the top of the charts. You are thinking that this is the pop music shot in the arm that will cause a zillion listeners to go into an appreciative trance and head over to the nearest music store.

It all comes crashing down the first time you hear your local nationally consulted radio outlet squash the life out of your pop opus, right as the first chorus makes its big entrance. Even that magical moment where the singer delivered the heartbreaking hook was lost in a sea of swimmy effects. What happened?

While it is a good bet that many of the most formative musical moments in our lives arrived courtesy of tiny transistor boxes, single-dashboard-speaker car radios, and other less than ideal audio setups, none of us as kids realized the degree of processed sonic mangling stations employed to deliver those magical sounds.

I knew I hit a hot topic when producers, engineers, and mastering engineers lined up to speak their minds. The following are a number of those very folks—names most of you know quite well—taking their turn with solid advice, horror stories, and the occasional dig at those broadcast mediums that have caused us as professionals to pull our hair out with frustration, while having to admit that our lives would be very different without them.

I would like to thank John Agnello, Michael Brauer, Greg Calbi, Richard Dodd, Don Gehman, Brian Lee, and Benny Quinn for their generous gift of time and insight for this chapter.

Credits include: The Breeders, Dinosaur Jr., Redd Kross, Screaming Trees, the Grither, Dish, Buffalo Tom, Triple Fast Action, Bivouac, Lemonheads, Tad, Gigolo Aunts. See the Appendix for John Agnello’s full bio.

Obviously, before music television, a lot of people mixed for radio, and a lot of those records were mixed for radio compression. There are a couple of different schools of thought. One is that you make it sound slamming on the radio, and when people buy it and bring it home, they get what they get. Another school of thought is to not really concern yourself with the radio. Then there is the guy in the middle, which is what I think I try to do. At least back when I was really concerned with radio, I tried to make a record sound kind of punchy on the radio, but not like a whole different record when you brought it home and listened to it on a regular system without the heavy radio compression.

For me, I just like the sound of bus compression on the mix anyway. I am a big fan of that stuff. When I was mixing more for radio, I would have the whole mix up and basically sit there with this really hard line compressor that was cranked at 20 to 1. I would check vocals and work on the mix, so I could tell what the radio might do, while monitoring through the compressor. This would help you tell how much of the “suck” you would get from the radio.

In fact, I would go to tape with the compressor, but not at 20 to 1. I would go back to more of a normal setting. MTV is here, but most people still listen to TV on a little mono speaker. Phasing is a main concern. If your snare drum is out of phase and it comes out on MTV, there is not going to be any snare in that mix. Phase cancellation is the correct term of what has taken place.

I use the Phase button more than I use the EQ button, especially on drums and things like that. Also, check the phase if you have a bass DI and a microphone, or if you are running a bunch of different mics on a guitar amp. You should always check the phase on those. If you are really careful about that kind of stuff, you can actually mix for maximum rock, as opposed to constantly EQing something that is screwed up on a different level.

I think that it is really important to regularly reference your mix in mono, if you are really concerned that your records really slam on MTV or any kind of music television. You can really tell how well your vocals are going to come out if you work in mono at lower volumes, and referencing on different speakers is also a good way to get a sense of your mix.

Credits include: The Rolling Stones, Bruce Springsteen, Jackson Browne, Billy Joel, Luther Vandross, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Michael Jackson, Jeff Buckley, Tony Bennett, Eric Clapton, David Byrne, Coldplay. See the Appendix for Michael Brauer’s full bio.

Over the past few years, the approaches to mixing for radio and for albums have become almost the same. This is because of the need for the recorded signal to be printed on tape or digital as loud as possible, with the possible exclusion of classical and jazz music, because those musical forms are so pure, and compression would be heard immediately. No compressors of any kind were used for my Tony Bennett Unplugged mixes.

The mixer accomplishes this task by using an array of compressors to keep the audio dynamic range down to 2 to 3 dB. The mastering engineer takes over and has his own custom-made toys of A/D converters and secret weapons to make the CD as loud as those little 0s and 1s can stand.

Radio stations have their own limiters and EQs with which to process their own output signal, in order to make things as loud as possible. The less you do to activate those signal processors, the better your song will retain its original sound. The potential problem is that you can end up with a mix that has no dynamic excitement left to it. It’s been squeezed to the point of being loud, but small.

Over the years, I’ve found ways to get the most dynamic breathing room possible within the 2- to 3-dB window. I break down my mix into two or three parts instead of putting my mix through one processor. The bottom part of the record (A) includes bass, drums, percussion. The top part of the record (B) includes guitars, keys, synth, vocals, et cetera. The third part (C) is sometimes used for vocals or solos only. I assign my reverbs to A or B, depending on their source.

The dynamics of the bottom end (A) of the record are no longer affected by the dynamics of the top part (B) of the mix. Once this concept is understood and executed, you then experiment by getting A to effect B, B to A, or C, et cetera. When done properly, the bottom of the record pumps on its own, independent of the top end of the music.

The problems I used to have with just using a stereo compressor became a vicious cycle. If I wanted a lot more bottom, the compression would be triggered and work harder, causing the vocals to get quieter. If I wanted more vocals or more solo instrument, my drums and bass suffered. By the second or third chorus of a song, the dynamics need to be coming to a peak. You don’t want the compressor holding you back. Ten years ago, the use of a stereo compressor was less of a problem, because the dynamic audio range was smaller. TR-808s and Aphex changed all that.

My mix of Dionne Farris’s “I Know” is typical of this style of mixing. The bottom end just keeps pumping along as the vocals and guitars have their own dynamic breathing room, all within that little dynamic window. The complete album, video, and radio mixes are all the same.

Credits include: Paul Simon, John Lennon, David Bowie, Bruce Springsteen, Norah Jones, Beastie Boys, Bob Dylan, John Mayer, the Ramones, Talking Heads, Patti Smith, Pavement, Dinosaur Jr., Brian Eno. See the Appendix for Greg Calbi’s full bio.

In a very petty sense, people are very conscious of their records being louder than everybody else’s records. Everyone wants their mastering to be louder. We are having a lot of problems with that, because people are cutting these CDs so hot that they are not really playing back well on cheaper equipment, and a lot of people have cheaper equipment.

Many mastering guys have gotten disgusted because it has really gotten to a point of diminishing returns. Why are we making them as loud as this? It is because musicians and producers all want a more muscular sound, but if they were all taken down a couple of dB, they might sound a little cleaner.

This is an example of almost like a lack of confidence. Everybody wants that little extra edge. If they feel volume is one of those edges, then that is something that I can give them, because all I do is turn the 0 to +1, and it is all of a sudden louder. The fact of the matter is, if you give radio something, and their compressors hit it the right way, and you have it tweaked up right, it is going to sound loud anyway. If your record is bright and clean, it will cut through a small speaker on a car. If it is really busy and dense, you will get that muffled quality.

Someone recently talked to a guy on radio who said that he likes to get stuff that is real low level off the CDs, so his compressors at the station can kind of do their thing. He felt it made stuff sound better than stuff that was really hot. We always thought that the hotter you cut it, the hotter it was going to sound on the radio. Well, suddenly, here was another twist on that debate. I thought, “Now this really takes the cake, because I’ve heard everything.”

I have a feeling that things sound great on the radio, more on how the parts are played and the whole thing is thought out from the get-go. The other day, I heard a Springsteen song, “Tunnel of Love,” on the radio. It sounded great, and it was so simple. The bass was down there playing the part. Guys like Springsteen and Bryan Adams write and arrange songs that are in the range that are made for radio. They give you one thing to digest at a time. There aren’t all these layered parts conflicting with each other. These are some basic tenets of arranging that kind of hold up on a little speaker. In my opinion, I think it comes more from the conceptual stage.

Credits include: Tom Petty (solo and with the Heartbreakers), Dixie Chicks, Boz Scaggs, the Traveling Wilburys, Wilco, Robert Plant, the Connells, Clannad, Green Day. See the Appendix for Richard Dodd’s full bio.

Here’s an analogy. We have a pint glass to fill, and with reference to mixing to radio, the broadcast processing makes it a point to always keep that glass full. If we under-fill it, their system will fill it. If you overfill it, or attempt to, it will chop it off. That only leaves us with control over the content of that glass. It can be filled with a few thousand grains of sand, a few small rocks, or a mix of both. Those are the parameters we have to work with. We make those decisions.

The stronger the song, the stronger the performance, the less we need. If the song or performance is perhaps lacking, we tend to go for the denser, thicker (more sand) approach. That is the control we have, but basically, there is still only so much that can fit in the glass. That is just the way it is.

If you want a voice and guitar at the front of the song to be X6, and when the band kicks in to be at least 0, you are never going to hear it like that on the radio. The nature of the compressor is to bring the quiet things up and the loud things down. But, if you use that facility correctly, then you can get the radio compression to remix the song for you.

I’m not going to make music for the type of processing radio thinks sounds right today, because tomorrow they are going to think something else is right. Then every piece of music that I made today is wrong. So I don’t mix for the radio, but I do mix with the radio in mind.

Even though you can’t have the dynamic, there are ways to create that sense of dynamic on the radio. I take things out. I turn the band down. It is under-mixing. Otherwise, without witnessing what happens through a second set of limiters, you don’t stand a chance.

A slower-tempo song can be apparently louder than an up-tempo song. If you have a drummer bashing away at 100 miles an hour, it is going to eat up all the space, and there won’t be room for anything. Remember that whatever is bad about a mix, the radio is going to emphasize it and make it worse. If you have something that is really laid back, with all the space in the world, that allows time for the effects of radio to recover before they act again, that can also be an effective dynamic, which you otherwise wouldn’t have gotten with the fast, busy track.

By extracting from the content, you can compensate for the lack of dynamic in a song. Less is more, basically, and extraction is part of the trick. It is in taking away, even if it is just using the facility to bring what you took out back again.

We all want to fill the glass to the top, but the only facility we can affect is content density.

Producer credits include: Tracy Chapman, R.E.M., John Mellencamp, Hootie & the Blowfish. See the Appendix for Don Gehman’s full bio.

I think the key to a great-sounding radio mix is to get your balances correct. I’m not just referring to the correct balance of basic core elements, like snare, vocal, bass, and guitar, but the frequencies within them are what have to be balanced as well. That way, everything hits the compressor with equal power.

I used to always use bus limiting, like on an SSL or this little Neve stereo compressor I have. For many years, I just let that thing fly with 8 to 10 dB of compression and just flatten everything out. When it went into mastering, I would have people sometimes complain that it was a little over-compressed, but they could work with it. They might say they couldn’t bend it into the frequency ranges that they needed.

I have been working with Eddy Schreyer over at Future Disc Systems, and he has encouraged me to use less limiting and more individual limiting and get my balances right. It has taught me a valuable lesson.

What we are doing now is I’ll try and contain that bus limiting to 2 to 4 dB, just enough to give me a hint of what things are hitting at. It is kind of a meter of which things are too dynamic. I’ll then go back and individually limit things in a softer way, so that the bus limiter stops working. Then I can take it in and put it on this digital limiter, which is this Harmonia Mundi that Eddy’s got, which is invisible. It doesn’t make any sounds that are like bus limiters that I know. We just tighten it up just a little bit more to give it some more level to the disc. That results in something that doesn’t sound compressed. It is very natural.

You can hit a radio limiter and have something that is very wide-open sounding, if the frequencies, like from 50 cycles to a thousand cycles, are all balanced out, so that they hit the limiter equally and your relationships aren’t going to move. They are all going to stay the same, but you’ve got to get that all sorted out before it goes into that broadcast limiter.

The way you do that is by using some example of it, to kind of test out. I use a bus limiter to kind of show me where I am hitting too hard, and then I take it away and get rid of it and let the mix breathe. That is the trick that I am finding more and more in helping get your balances just right.

With the whole practice of frequency balancing, I know you can have tracks that seem dynamic on radio. Green Day’s “Longview” is a great example. That chorus slams in, but it is balanced out well enough that when the chorus hits the limiter, it just adjusts the level and doesn’t gulp anything else up.

If you have bass frequencies that come in too loud and aren’t balanced in the midrange, the limiter “sees” whatever is loudest and puts that on top. If the low end is too loud, then everything will come out muddy when it hits. If all the frequencies are balanced, the limiter will equally turn down the balances, with them all staying intact, and life goes on just as you intended.

Credits include: Janet Jackson, Pearl Jam, Ozzy Osbourne, Gypsy Kings, Lou Reed, Gloria Estefan, Charlie Daniels, Cachao. See the Appendix for Brian Lee’s full bio.

It is very important to check for phase problems by referencing to mono regularly in the mix stage.

When you mix, you should definitely be listening in mono every now and then, so you know that when it goes to mono, it will still sound just as good and in phase. I believe that the fullness of the overall sound when you are in stereo can cause you to pay more attention to the instruments and effects than to the vocal.

Interestingly, a lot of people use phase for weird effects. We have done heavy metal albums that are really out of phase. They especially like to put a lot of effects on the vocal. Maybe they just didn’t think it was going to get played on the radio, but some stuff was totally out of phase, and if you pushed the mono button, everything just went away. We could’ve put everything back in phase, but I think they would think it would ruin the effect that they wanted.

It is important for producers and mixers to print mixes with vocals and other desired elements with higher and then lower settings, so as to allow the mastering engineer more flexibility in attaining the ideal presentation.

We do suggest that you get a mix the way you think it should sound and get a few different passes, like vocal up and vocal down. Mixing is very expensive, and you should get as much out of it as you can. If you are going to the Hit Factory or some studio like that, that is a lot of money a day. You don’t want to have to go back and rebook time and remix the whole thing just to get the vocal right. When you are mixing, you should also do your instrumental TV track and versions with lead and background vocals up and down.

If you have the time and patience to do that, you will be in great shape, because when you get to this stage of mastering, you can actually sit back and reflect and say, “I need more vocal on this particular section,” or, “I think this particular vocal is overshadowing this part of the song. I think it needs to be brought down.” Then you can do edits at that point.

When you are traveling around from studio to studio, listening and mixing, you may think a mix sounds great until you hear it on another system, and for some reason things sound like garbage. You may find yourself going, “What is going on here?” Usually, mastering is a third party’s subjective opinion about the whole process. That is one thing that the whole mastering process is about. We know our speakers very well, and when you bring your work in here, hopefully we will have some frame of reference for you to get it right.

Credits include: Eric Clapton, Elvis Presley, Aaron Copland, dc Talk, Johnny Cash, Isaac Hayes, Alabama, Dixie Dregs, Indigo Girls, Bela Fleck, Bob Seger, Cracker, Widespread Panic, Amy Grant, Boston Pops Orchestra, Willie Nelson, Nanci Griffith, Shirley Caesar, Lyle Lovett, Reba McEntire. See the Appendix for Benny Quinn’s full bio.

Mastering for radio is like a dog chasing its tail. It’s really a losing proposition in that you’ll never get there. Each radio station is different and processes their station differently than the one next door in the same building that’s playing the same music.

What most engineers—especially new mastering engineers—are not aware of is the fact that in FM broadcast, the FM standard requires an HF boost on the order of 15 dB at 15 kHz, and a complementary roll off in the receiver at the other end. What does that mean? It means that as we push more high frequencies onto the discs, the more the broadcast processors limit and roll that off.

Also, as we push the levels harder, with more clipping and smash limiting, we end up with more distortion that the processors interpret as high-frequency energy and roll it off even further.

The sequence is sort of like this: The processors measure the HF content and apply the pre-emphasis curve to see how far over 100-percent modulation the signal would be. Then, the overall level is turned down to allow that to fit in the station’s allowed transmission bandwidth. [100 percent is the legal limit.]

So, let’s say that the CD is mastered such that there needs to be a 5-dB level drop for everything to fit. Then the multiband processing is added, then transmitted. At the radio end, there is no information that says, “Oh, by the way, this song has been turned down 5 dB.” It just sounds duller, maybe smaller, and not like the record you mastered. The producer hears this on the radio and says, “Hey, it’s not bright enough or loud enough. Next time I’m really going to pour on the highs and limit and compress it.” Guess what happens? The next record sounds even worse.

What’s the answer? Well, if you listen to an oldies station that plays music from before the mastering level wars started, those songs sound great. If you listen at home to those same recordings, they have life, sound natural, have dynamic range, and are easy to listen to. Mastering for radio should be mastering for great sound. That’s what works for me.

Here are some more specific pointers to consider. Everything has got to be very clear sounding. You have to make sure that everything is distinguishable, as far as the instrumentation is concerned, and that can be done with a combination of EQ and limiting.

The low end is what will normally grab and kick a compressor or limiter at a station. If you have too much low end, and it is too cloudy and big, then all you will hear are the station’s compressors grabbing the low end and moving everything up and down with it.

While I typically don’t cut off the bottom end, I do try to make sure that the bottom end is clean and present. Normally, you will find frequencies in the low end that are rather cloudy. This changes from song to song and mix to mix.

You can often find one or two frequencies that may create more cloud than distinction. You may be rolling off at that frequency, using a really broad bandwidth and then possibly even adding back a very similar close frequency, maybe even the same one, using a very narrow bandwidth. What you do is take that cloud and that woof out of the low end. That usually helps significantly, as far as radio processing is concerned. The top end doesn’t seem to hit the station’s signal processing as hard as the bottom end, and radio compression doesn’t seem to hurt the top end as much as it does the bottom end.

Most rock stations compress more heavily than other station formats do. When something is out of phase, it causes very strange sounds in the reverbs. You will hear more reverb on the track, while played on the radio, if the phasing problem is with the original signal and not with the reverbs on the tracks themselves. The original signal will want to cancel, and the reverbs won’t, making things sound even more swimmy.