Chapter 15

Mindset

Over time, the technical execution of a mix becomes dead simple. I discovered this when I lost three mixing projects due to a broken hard drive. I had saved the stereo mixes on a different drive, but because I still needed to make some adjustments, there was no other option than to mix the three songs again. Disheartened, I started over, thinking that I’d need another day and a half to get everything back to the same point as before. But to my surprise, after a Saturday morning of mixing, the three songs were done. It felt like I already knew the solution to the puzzle and the way to get there, which allowed me to perform all the necessary actions on autopilot. When I compared my later mixes to my earlier work, I could only conclude that I had done even better on the new versions. Ever since, I have never been afraid to close all the faders and start over when a mix doesn’t work. The time is never lost. Because you’ve learned a lot about the music in the process, you can get back to the same mixing stage in no time.

Up till now, this book has mostly discussed the technical execution of mixing. But technique alone is not enough for a good mix. It can only help you to execute your ideas with more speed and focus. The essence of mixing is about how you form and develop ideas. It’s about how you keep track of them, or sometimes let them go. This chapter deals with that side of mixing. It’s about the mindset you need to get through the endless puzzle and still be excited to get back to work the next day.

15.1 Doubt Is Fatal for a Mix

Nobody who works on a music production can be certain about everything, as it’s impossible to predict the outcome of all the variables beforehand. This unpredictability creates room for chance and experimentation, and that’s exactly what makes working on music so much fun. The way you make use of the room you’re given—and the uncertainty that goes with it—is inextricably linked to mixing. Uncertainty goes hand in hand with doubt, and that’s where the danger lies. However, this doesn’t mean that doubt has no part to play in the mixing process. On the contrary: calling your decisions into question is essential if you want to make good choices.

While exploring the material, brainstorming with the artist and producer, shaping your own vision and quickly trying it out, there is room for doubt. During this exploratory phase, doubt is the engine that drives experimentation. It keeps you sharp and stops you from doing the same thing over and over again. You’re looking for an approach that feels good from the get-go, which also means turning down the options that don’t immediately feel good. This might sound shortsighted, but it’s necessary, as there are simply way too many possibilities to thoroughly consider. It’s better to trust your intuition and go for something that feels good right away.

Once you’ve decided to go with a particular approach, the exploratory phase is over and—at least temporarily—there is no way back. From this moment on, doubt is dangerous. You are now entering the execution phase of the mix, which requires complete focus. You work quickly, decisively, and without looking back. It’s okay to still have doubts during this phase (after all, you’re only human), but only about the execution of the plan. These doubts are very welcome as well, as they force you to be precise and fully optimize the plan. But as soon as the doubts start to spread to the plan itself, you’re lost. Mixing is pointless if you don’t know what you’re going for. If you change the original plan, you throw away almost all the work you’ve done up till that point. To avoid this, you’ll need to let go of your doubts while working on your mix, and take off the training wheels of external input, reference tracks and rough mixes. You’ll have to fully trust your own ability and the material you’ve been given. But what if it turns out that your plan doesn’t work? Well, I guess you’ll have to cross that bridge when you get there. It’s pointless to reflect on half-finished products—do something with conviction and see it through or don’t do it at all.

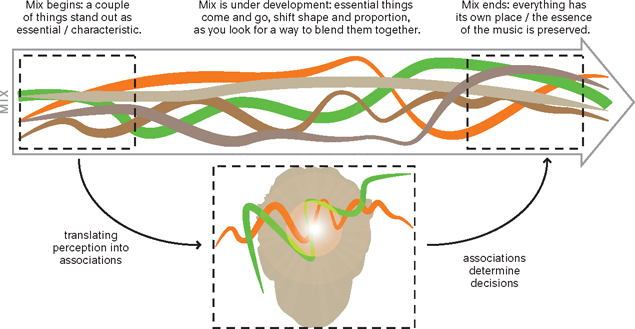

Figure 15.1Doubt is often useful, except if you have to decide on the direction of the mix.

It sounds quite rigid to approach a creative process like mixing in this way. But if you want to get anything done at all, and get around to the choices that will really make a difference in a piece of music, you can’t get stuck too long on choosing a direction. Each time you have to go back to the drawing board to adjust the original concept is actually one too many. If necessary, just take the rest of the day off and try again later. Or start working on another song instead. I would even go as far as to say that making a less ideal choice is better than looking for the perfect one for too long. After all, you have no idea what the implications of your choice will be at the end of the ride.

Sometimes you just have to start and don’t look back to see if you had it right. If you beat around the bush for too long, you’re wasting all your enthusiasm and objectivity on a concept that may or may not work. So it’s always a gamble, no matter how much time you put in. This is exactly what separates experienced mixers from beginners: they don’t necessarily make better mixes, but during the formative phase they’re quicker and more focused in making choices based on gut feeling.

Decisive Action

Mixing has nothing to do with unlimited creativity. It’s creativity within a context, and you’re expected to deliver instant results. In a way, it’s a lot like playing improvised music. The context is clear, the agreements have been made, you know your instrument, and the rest will become clear within a few hours. If you want to mix on a regular basis, your mixing process should be reliable first and foremost. You have to be sure that there will be something useful at the end of the session, even if it’s not your most brilliant performance. Therefore, experienced mixers are good at making decisions: at a certain point in the process they choose a direction and follow it through to the end. There are two challenges when it comes to this: first of all, your choice shouldn’t be based on a wild guess. The more you know about the music, production and artist, the more certain you can be of your choice. And second, you want to choose as quickly as possible, because this means more time for the execution of the mix, plus your focus and objectivity won’t be so low that your work becomes unreliable. You’ve probably noticed that these two challenges contradict each other. You want your choice to be as informed as possible, but if you postpone it too long, you won’t complete the mix successfully before your ears get tired.

Figure 15.2There are a few moments for reflection and discussion with your client, but during the execution of the plan there’s no room for distraction or looking back. For live mixers, it’s self-evident that there can only be discussion during the sound check and after the concert, as it requires their full focus to successfully complete the execution. Ideally, it should work the same in the studio, but don’t expect all parties involved to also realize this. If you don’t pay attention, the execution phase will be used for feedback as well, which is disastrous for your focus. Therefore, after the preparatory phase is over, you’ll have to consciously create room for the execution.

Live

If you have a hard time making pragmatic choices, it can be very inspiring to mix live concerts. The feeling that you only get one chance to make it work will dispel your doubts in no time—there’s simply no time for doubt—and help you to let go of the idea of perfection. A mistake is not a disaster, as long as the big picture is still convincing. However, you shouldn’t think that a studio mix is the same as a live mix, as a studio production requires a more precise execution. But during the early stages of the mixing process, perfection is a ball and chain—and meaningless at that. If you first make a sketch like a live mixer, the time you spend perfecting the sound won’t be wasted. You need to put all the important things in place first, otherwise you won’t know what you want to perfect.

The solution is to learn to sketch as quickly as possible. After all, the only way to know which ideas have potential and which ones can be written off is by trying them out. The setup of your studio and mix template has a huge influence on your working pace, and so has your repertoire of ‘universal solutions’ for common mixing problems. Your sketches won’t just help you to make decisions, but also serve as a means of communication. An audio example will tell your client more than a thousand words. Through efficient sketching, you can get to a mixing vision faster, while reducing the risk that it falls short, or that it clashes with the producer’s vision (see Figure 15.3).

Figure 15.3The time during which you can stay objective, focused and creative is limited. That’s why it’s so important to structure the first part of the mixing process well. Executing and refining the mix can still be done after you’ve lost your focus a bit, but devising and testing new concepts is no longer possible at the end of a session. Complex mixes are a challenge, because when you call it a night and continue working the next day, there’s a greater risk of questioning your original concept. The earlier and clearer you define your vision for the mix, the more reliable the process will be.

Be Nice to Yourself

No mix is perfect, and no mix is ever ‘done.’ You could keep working on a mix forever, but at some point you have to decide that it’s finished, if only due to a deadline or a limited budget. I wish it were different, but that’s the reality of mixing. Live, this is much easier to accept, as you simply can’t control everything. But in the studio, it can be frustrating: you’ll always hear aspects in the music that could still be improved.

Your perception can be a burden, because in reality there is a point when the mix is really done. It’s just that this point isn’t defined by the moment when everything is perfect, because that doesn’t exist. The mix is done when the essence of the music comes across to the listener, when all parts in the arrangement fulfill their role, and when the objectivity of the mix engineer has reached its end. If you can’t tell anymore if something helps the music or not, you really need to stop.

The latter isn’t always easy. Some productions contain contradictions, which means you have to make huge compromises in the mix to still make it work. For me, it’s always hard to hear these mixes again later. Even though the mix might have turned out okay, and though it works in the sense that the music comes across, I only hear the compromises I had to make. I’ll keep wondering if there couldn’t have been a better solution. If I have to make objective decisions about such a mix again (for instance, because the producer still wants to change things), I make sure to protect myself. From that moment on, I use my main monitors as little as possible, and make as many adjustments as I can on small speakers. This way, I’ll mainly hear the essence of the music, and not so much the details. It makes it easier for me to preserve the essence of the mix without questioning all my previous decisions. The worst thing you can do during this minor adjustment phase is to smooth out your original approach too much. After all, this is the very approach that convinced yourself, the artist and the producer that it’s time for minor adjustments.

As you can tell, we’re reaching the point where mixing can be a fight against yourself. The final stage of a mix is the perfect opportunity to start doubting your own abilities, to be intimidated by the way (already mastered) reference tracks compare with your mix, to wonder if your speakers are playing tricks on you, and so on. Add to this the assignments that are called off because clients aren’t satisfied with your approach (this happens to the biggest names in the business—mixing is still a matter of taste), and you have a recipe for getting seriously depressed about what you’re doing. It’s not a bad thing at all to be critical of your work—I don’t think I’ve ever delivered a mix I was one hundred percent satisfied with—but there’s a point where it ceases to be constructive. Fear leads to gutless mixes. If you don’t dare to push on with your vision for the mix, the result will be reduced to a boring avoidance of anything that could potentially disturb anyone. In the end, not too much of this and not too much of that means very little of anything.

It helps to think like a musician on a stage. Above all, mixing should be fun: you should be able to lose yourself in it and make decisions without fear of falling flat on your face or being judged. If you don’t feel this freedom, your decisions will never be convincing. And what if you’re all out of ideas for the moment? Then don’t be too hard on yourself, and simply trust the people around you. Every day, my clients help me to be a better mixer, by pointing me to things I had overlooked, or by proposing alternative approaches. It’s nonsense that you can instantly understand everything about a song. If you want to do your job well and with conviction, you need to give yourself some space. Sometimes you just have to try your luck to hear how an idea turns out, and laugh about it if it fails. Sometimes you have to be brave enough to hold on to your first impulse without getting thrown off by the drawbacks that are bound to come with it. Sometimes you have to admit that the artist and producer are right when they say your mix isn’t working yet, and other times you have to trust them when they say your mix is awesome, even though you’re not so sure about it yourself.

One thing can never be called into question during mixing: your process. You will need an almost religious belief in it, because whoever said that it’s better to turn back halfway than to get lost altogether was definitely not a mix engineer. It’s only after the mix is finished that you can afford to think about methodology, and preferably not more than a few times a year. Being biased about the effectiveness of your own way of doing things—and the gear you use—will help you to reach the finish line with a sense of conviction. If you start wondering halfway if the compressor you’re using is really the best compressor ever, you could easily end up with a remix. This is why only your mixing decisions can be the subject of debate: whether you use the compressor, and how much. Don’t question the fact that you always use the same compressor for a certain purpose. ‘You can’t change the rules of the game while you’re still playing’ would be a good slogan for any mixer to frame and hang on the wall.

15.2 Imposed Limitations: Working in a Context

It’s tempting to try and emulate the sound of your favorite productions with your mix. But while it’s always good to be inspired, it really shouldn’t go any further than that. Before you know it, your ideal is defined by the technical execution of another production. When you close your eyes while mixing, you think about your great example and try to approximate it. But what a hopeless undertaking that would be! If there’s anything that doesn’t work, it’s trying to apply the production and mix of one song to another. The guiding principle should always be music that comes across well, and if it sounds good on top of that, you’ve done even better. The music dictates the technique.

So music that comes across well is not the same as music that sounds good? For average listeners, it is the same: when they enjoy a piece of music, they look at you, blissfully nodding, and say: ‘Sounds good, huh?’ Meanwhile you, on the other hand, are still annoyed by excessive distortion and dominant bass. This is an extremely important thing to realize: the only people in the world to whom music that comes across well doesn’t mean the same thing as music that sounds good are sound engineers. To a lesser extent, this also goes for producers, labels and some artists. You could say that mixers carry the weight of an insider’s knowledge about how sound works, and how you can solve problems to make the sound more defined, balanced and spacious. But what if the music needs something else? The question should always come from the music, and shouldn’t be prompted by technology.

The best way to prevent yourself from making everything as polished as possible is to deny yourself that possibility. Your best clients—those who push you to your greatest creative achievements—will do this for you. For example, because they have already recorded all the vocals through the PA of a local house of prayer, the production might sound a bit distant and messy, but it’s a huge statement. Now you can put all your effort in giving the sound a bit more focus, but it will never be polished. Things would be very different if these clients were to give you all the raw vocals as well. After all, these tracks do sound close and full and warm and nice and technically oh so good. But as you start blending them with the manipulated recording, you stop noticing how meaningless the raw vocals are in this musical context. And that’s what it’s all about.

Mix engineers deliver their best work when they’re severely restricted in terms of artistic direction, because otherwise they will use all the space they get (see Figure 15.4). This means that if the producer doesn’t make any decisions to set these boundaries, the mixer will have to. However, this turns you into a kind of eleventh-hour producer, plus you won’t get around to the finesse of your mix. Your entire role as a translator of an idea has been shifted to being the co-author of the idea. So now you have to run those damned vocals through the PA of the house of prayer yourself.

It takes time and objectivity to map out (part of) the artistic direction. Afterwards, your ear for what the vocals need in the mix won’t be sharp enough for you to still be independent as a mixer. Your qualities as a mix engineer will go down, simply because you’ve bitten off more than you can chew, and it can be a thankless job to do more than what’s in your ‘job description’ as a mixer. It’s for this reason that I would negotiate such an expansion of my employment separately, especially since it could mean running into things that can only be solved by going back to the recording process. On top of this, you’ll need to take more time if you still want to be able to approach your mix as an individual project, because a producer is not a mixer, even if he or she is the mixer. If you perform both tasks yourself, it’s advisable to keep them separated: first delineate the concept (production) and then translate it (mix).

This scenario happens a lot in electronic music, where the producer is often the composer and mixer as well. This seems like a very simple situation in which you don’t have to answer to anyone, but at the same time I can’t think of a more difficult way to convincingly get a creative concept off the ground. If no external restrictions are imposed and no frameworks are given, it’s very hard to stay on course. With nothing to hold on to, you can keep trying different directions, which can make the production process inefficient and frustrating.

Figure 15.4Contrary to what you might expect, mixers don’t like having a lot of options at all. The lines that spread out from the source material represent the directions you could take with the material. If enough of these directions have been blocked during the production stage, before the start of the mix (the red Xs), your mission as a mixer is clear (A). Deferred choices that are meant to give you more freedom actually frustrate the mixing process (B), as the latter should be about translating a concept, not about creating a concept for music that has already been recorded.

If no one imposes restrictions on you, you’ll have to do it yourself. Whether you have to blend eighty middle-of-the-road tracks into a whole that will still sound fresh and different, or build a dance track all by yourself with your computer, the sooner you choose a direction, the better. Choosing also means blocking the possibility of changing your mind. You found a cool sound? Just record it and never look back. You’re stuck on a transition that fails to impress? Then remove some parts from the previous section to make it work. You found a sound that can determine the character of the song? Turn it all the way up, so the other instruments will simply have to make room for it.

Do hard and irreversible choices always lead to success? No, sometimes you run into restrictions that turn out different in the mix than previously expected. Some problems won’t emerge until you really get into the details of the mix. Then it’s time for consultation, and hopefully the problematic parts can be re-recorded or musically adjusted to make the mix work. This method is still very targeted, and it’s better if the direction of the production is completely clear and some things still have to be changed later, than having to sort through a myriad of deferred choices, which initially seems very flexible.

15.3 A Guide for Your Mix

It’s already pretty hard to choose a direction for your mix, but holding on to it is at least as tough a challenge. A mix is an awfully fluid thing: you change two things, and your entire basis seems to have shifted. That’s dangerous, because before you know it, you’ve forgotten what it was that made the music so special when you first heard it. But changing nothing isn’t an option either, as your mix definitely won’t get anywhere that way. So you need a way to keep your balance, in spite of the transformations your mix is going through.

Initially, the direction you choose is purely conceptual, and you won’t make this concept concrete until the execution phase. In order to do this well—executing a mix without losing sight of your concept—you need a way to capture a conceptual plan. Insofar as the plan contains concrete actions or references, this won’t be a problem, but usually the main part of the plan is a feeling or a set of associations that you have formed— mostly as a result of listening to the source material and talking to the artist and producer. This first impression of the music is hard to describe, but it’s of vital importance to the success of your mix. It’s no surprise that a mix with a concept that’s based on how it felt when you first heard the music will work better than a mix that’s based on a meticulous analysis of all the details in all the parts. This poses a big challenge, as you have to come up with a way to preserve the feeling you had during the initial phase of your mix, so you can still base your decisions on it at the end of the day.

Be Open

If you want to use your initial feeling as a tool, first of all you have to be open to it. This might sound like something you’d rather expect from a woolly self-help book, but it’s necessary. However, this doesn’t mean you have to take a Zen Buddhism course, but you do need an empty head, calmness and attention.

The first time you listen to a piece of music should be a conscious experience, so the music will have the chance to settle into your mind. This is why I never play a project in the background while I’m still busy preparing the mix setup. I prepare what I can without hearing the music (routing, naming, sorting and grouping of the tracks, arranging the mixing board, and so on). When that’s done, I grab a fresh cup of coffee and quietly listen to the entire production. I prefer to start with a rough mix that clearly conveys the idea. But if this isn’t available, I simply open all the faders, and if things annoy me, I quickly turn them down while I keep listening. This is the closest thing to walking into a venue and hearing a band play without prior knowledge, or hearing a song for the first time at a party or on the car radio. If it’s a live mix, you could start by having the artists play together on stage without using the PA. This way, you’ll notice how they react to each other and who fulfills which role, before you start manipulating this with your mix.

Figure 15.5Consciously registering your first impressions of a mix in the form of associations makes it easier during the final stage to still distinguish between the main elements (which make the music and mix unique) and the secondary ones (which support the main elements).

Sometimes I take notes, but usually I absorb the music mentally and start free-associating. You can see this as consciously creating connections between your feelings and concrete references. These connections help you to remember your feelings, just like it’s easier to remember all the names of a group of new people if you consciously connect them to a physical feature or to someone you know who has the same name. In Figure 15.5, the principle of this way of working is visualized.

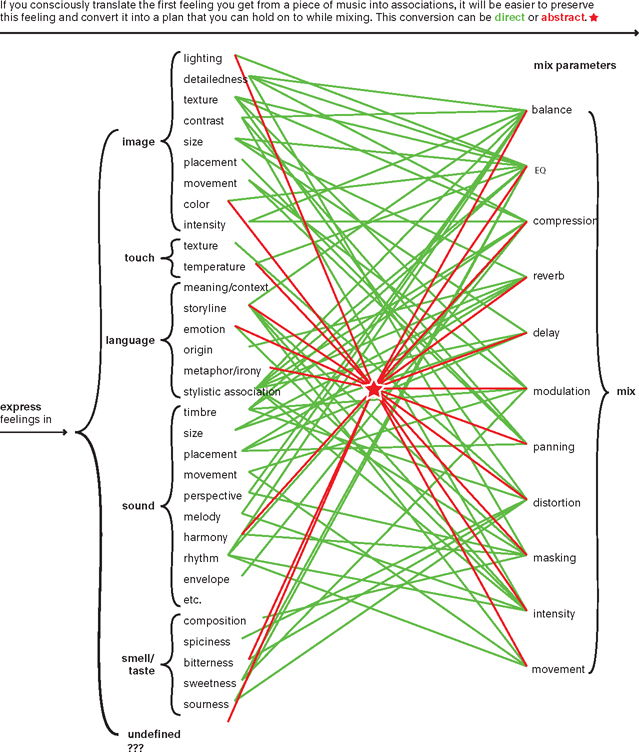

Translate

Preserving your feelings is the starting point, but you won’t be able to use them as a tool until you can convert these feelings into concrete mixing decisions. In order to visualize how this process works, you could draw a huge diagram in which you would have to display the complete histories of the composer, musicians, producer and mixer. Their fears, loves, influences, origins, upbringing, experiences, character, everything. All of these things converge at a certain point in the diagram and start to affect one another, which eventually leads to all kinds of decisions. Such a diagram would be infinitely complex and almost by definition incomplete. This is why, in the art world, this process is often simply referred to as ‘magic,’ ‘inspiration’ or ‘creativity.’ Great, all these vague concepts for the most crucial part of the creative process. Sadly, it’s hard to make these things more concrete, because the translation of your feelings into practice is exactly where the greatest artistic freedom lies. This conversion works differently for everyone, and therefore, by definition, music sounds different when it’s mixed by someone else. In that sense, imitating someone else’s mix is like trying to fall in love with the same type of person as someone you admire, which is never going to work. Still, there is more to be said about how this magic can come about, as a significant part of it is actually not so magical—it’s mainly about estimating what’s important for the music, and then drawing on your knowledge of how you could accentuate this in your mix. In these cases, there’s a relatively direct connection between your perception, associations and mixing decisions. Another part of it is in fact more abstract, and if you want you can use the word ‘magic’ for that. Or call it ‘chance,’ ‘revelation from above,’ or whatever floats your boat (see Figure 15.6).

Storyline

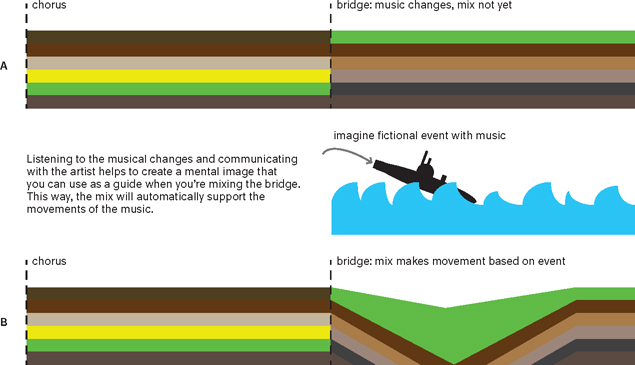

If all of this is getting a bit too vague for you, or if it’s already in your system so you don’t have to consciously think about it, there’s another concrete and easy-to-implement principle you can use to direct your mixing decisions: all music has a story. It takes you from one point to another, and things happen on the way. These musical events keep the music interesting to listen to, and therefore it’s important to emphasize them in the mix. This is a lot like mixing music and sound for a film, except that the events on the screen are prompted by the scenario, not by the music. Since these cinematic events are much more concrete than when you work with music alone, it’s easier to make distinct mixing decisions. When I mix music for movies or live performances, I always find myself having fewer questions than when I only hear the music. The images dictate when what is important; they determine the course of the mix.

Figure 15.6The method I use to hold on to the feeling I get from a piece of music when I hear it for the first time. By consciously registering my associations, I create a memory that I can call up later in the process, and then translate it into mixing decisions. Often, a large part of my feeling has little to do with how others perceive the same piece of music. Therefore, it’s not my intention to translate it literally so you can recognize it in the music—the conversion is usually much more abstract. I mainly use these concrete associations as a memory aid, to bring me back to the moment when I first heard the music.

If there is no (visual) story, you can also create one yourself. You can come up with a music video to go with the song you’re mixing, or play a movie in the background with a mood that matches the music. In an interview with mix engineer Tom Elmhirst (by sonicscoop.com), I read that he regularly plays movies in the studio while mixing, to keep having images to connect with the music. For me, it often works well to create scenarios for transitions that aren’t powerful enough yet. This is also a very effective way to communicate with artists and producers about where a mix should go. A songwriter once made it clear to me what had to happen in the transition to the bridge by telling this story: ‘You’re at a party among friends, but you start to feel more and more alienated from them. Eventually, you take a big jump and dive into the swimming pool to close yourself off from the outside world. Underwater, you become completely self-absorbed.’

Images Are Just like Sounds

Many visual features have a sonic equivalent, and connecting these two can help you to get a better grip on the meaning that you give to a sound. For example, it’s very tempting to make everything big and impressive, until you ‘see’ that a certain element should fulfill a much smaller role in the image, and be anything but prominent. Personally, I find it a lot easier to render the various roles and spatial parameters in a production visible and tangible than audible. Equalizing something very brightly is the same as overexposing a photo, and using compression is the same as adding a lot of extra detail. Many principles from the visual arts about composition apply directly to mixing, and vice versa. The visual connection can also be much more abstract, and take place at an emotional level rather than through very concrete associations.

Figure 15.7Mixing a song based on a (made-up) story motivates you to create powerful, unambiguous movements. A single image of a submarine going underwater can lead to dozens of mixing decisions, in a very intuitive way.

A concrete storyline like this can be a stimulus for hundreds of mixing decisions, all of which serve the same purpose. The result of such a connection is a mix that makes a powerful statement: your goal is to create an event that’s told by all the instruments, not a random balance in which the instruments just happen to sound good together (see Figure 15.7).

Your audience usually won’t have any idea of the underlying ideas that brought you to a particular mix. Which is good, because if you communicate these ideas too literally, your listeners can’t develop their own feelings with the music. Therefore, the goal is not to convey your own associations, but to use them to give your mix a certain structure. The audience can feel the difference between a structured mix and one that results from arbitrariness. A structure can really give a mix a distinct character and a narrative quality, which is more likely to evoke feelings in the listener than something that only sounds nice but that’s pretty randomly put together. You can compare this principle to an abstract painting: you can give the viewer too much, but also too little structure to hold on to.

15.4 Ways to Stay Fresh

Take Breaks

The longer you can stay objective about your own work, the greater the amount of reliable work you can get done in a single day. In this case, ‘reliable’ means that you and your clients will still be satisfied with it the following day. Besides training your ability to concentrate (by mixing a lot), taking breaks is the best way to expand this window of objectivity. But it’s not as easy as spending twenty minutes at the coffee machine every two hours, like they do at the office. An ill-timed break can also make you lose your grip on a project. Simply taking a hike in the middle of a process or a train of thought is not an option, as this sometimes means you have to do the whole thing again after you come back from your break. A break can help you to take some distance from already completed subprocesses, so you can evaluate them with fresh ears. For example, your first mix balance won’t mean anything until it’s done. It’s pointless to reflect on it halfway, as this will only allow the doubt that rears its ugly head after each break to sneak into your process. It’s for this reason that I always have lunch at different times, depending on where I am in the process. I should add that to me, a break means no music, so no reference tracks by other artists either. I don’t let the artist have another listen to the mix while I’m taking a break, and I don’t perform minor edits that are still on the wish list. Preferably, I spend some time outside the studio, in different acoustics with different ambient noise. I would almost consider picking up smoking . . .

Distraction

One of the reasons to take breaks is that your ears get used to the sound they have to cope with (see Chapter 2). This is what makes a piercing guitar pop out of the mix the first couple of times you hear it, while later it seems to blend in just fine, even though you haven’t changed a thing. This kind of habituation creeps in when you listen to the same sound for an extended period of time. So even if you don’t take breaks, it’s a good idea to not constantly play music. All the work I can do without sound coming from the speakers, I do in this way. For naming, cleaning up tracks and routing you don’t need any sound. For editing you do, but you don’t always have to hear the entire mix. So this is one of those rare cases where the solo button does come in handy: when you’re removing noises or clicks from an individual part, it’s fine (or even better) to do this by isolating the track.

Switching to a different type of speakers can also help you get a fresh perspective on your mix, although it can also be confusing if you don’t know exactly what to expect from a particular speaker. A less drastic solution that will still work very well is briefly switching the left and right channels. This way, many instruments are temporarily located somewhere else, so it will be more like hearing them for the first time. If the piercing guitar from the example was originally panned slightly to the right, its shrillness will stand out more when it suddenly comes from the left. It’s important to be alert when you listen to the result, because after you’ve heard your mix twice with an inverted stereo image, the novelty has already worn off.

You can also try to reset your ears with other sounds. And I don’t mean intimidatingly good-sounding reference tracks that have everything you’d want your own mix to have, but a completely different sound. This won’t keep your ears from getting tired, but it can rebalance your reference of the frequency spectrum. After you’ve watched some random nonsense on YouTube, maybe you’ll suddenly hear how piercing that guitar really is.

Let Your Mind Wander

As much as I value silence when I’m not consciously working on the mix, sometimes listening with half an ear is the best way to signal problems. If you let your attention wander to your inbox, a television show or another source of distraction, you can suddenly notice a huge problem that was right under your nose all this time. All-important realizations such as: ‘If I turn the vocals down, the entire mix will fall into place,’ will sometimes only come to you after you create some mental distance from the mix. There’s a fine line between half-attentive listening and not listening at all, so it’s important to find a way that works for you. Personally, I become too absorbed in email and messaging to keep my thoughts open enough for the music. But checking a website or watching sports with one eye (and without sound) works perfectly for me.

Pragmatism and Deadlines

Creativity isn’t bound by time, or at least according to people who obviously aren’t mix engineers. It’s true that good ideas are difficult to force, but what you can do is leave as little as possible to chance. The day that I don’t finish a mix because I’m passively waiting for a good idea is the day that I’m replaced by another mixer. A large part of the mixing process consists of structuring and executing ideas that have already been conceived by others, or that are already part of your own repertoire. You can always fall back on these if you’re all out of ideas. Because you work so methodically, with tools and concepts you’re extremely familiar with, this creates a pleasant state of peace that allows you to be creative. The almost autistic nature you need to have as a mixer—and the desire to leave nothing to chance and always structure everything the same way—makes you confident enough to explore new creative directions. Meanwhile, your method helps you to suppress the fear that the mix won’t be finished or that it won’t work.

Pros and Cons of Mixing in the Box

Total recall, restoring all the settings of the equipment used to create a mix, was a time-consuming job in the analog era, something you preferred to avoid. Mix engineers tended to finish something in one go and live with it. Clients knew that adjustments were often expensive, and only asked for one if it was so relevant that it was worth the money. This balance is completely different now, since total recall is a matter of seconds on a digital mixing system. The advantage of this is that you can still work on another song after you’ve reached the end of your objectivity. I’ve found that this freedom requires a lot of self-discipline. For me, moving on to another mix when you get stuck and trying again tomorrow is not the way to go. It feels like you’re deferring choices and interrupting the research process that’s inherent to mixing. I want to struggle my way through it first, and only take some distance when my idea for a mix has been realized. That’s when the computer really proves its use. The artist, producer and I can then listen to the mix again at home, and after a week we’ll dot the i’s with a couple of tweaks. If you get stuck halfway, it’s pointless to evaluate the provisional result on your car stereo—you need a sufficiently developed idea.

Part of this method is setting deadlines. Not allowing yourself to try yet another idea, forcing yourself to move on to the next element and recording an effect (so you can’t change it anymore) can all be seen as deadlines. Deadlines force you to make choices, which in turn forces you to be pragmatic. An example would be if you can’t get the lead vocals and piano to work together. The vocals are more important, so if there’s still no convincing solution after twenty minutes of trying, the piano will have to make room by being turned down a bit. You might think that this kind of pragmatism is the enemy of perfectionism, and that it leads to carelessness. In some cases this could be true, but more often pragmatic choices keep the mixing process from stagnating, plus they make sure that there’s at least something to reflect on at a certain point. After all, it’s pointless to refine half-finished products—something has to be finished first, otherwise you can’t hear where you are.

Some insights require more time than available in a mixing process. It’s highly possible that, after mixing the first three tracks of an album, I suddenly discover the method that makes the vocals and piano work together. I can then go back to my previous mixes and make them work even better with some minor adjustments. On the other hand, if I had refused to turn down the piano during the first mix, I would have embarked on a frustrating course in which I could have spent hours looking for a liberating epiphany, completely losing sight of my objectivity. As a result, I wouldn’t be able to make any meaningful choices about the other instruments anymore, because I had already grown tired of the music. Pragmatism is necessary to protect yourself from such pointless exercises. The more experience you have, the easier it gets to be pragmatic. You can already predict the hopelessness of a particular search beforehand, and then decisively break it off.

By the time you’ve attentively listened to a song fifty times, small details will become more and more important to you. It can even go so far that you lose sight of the essence of the mix in favor of the details. When this happens to me, I switch to my small speakers and listen to the ‘bare-bones’ version of the mix, stripped of everything that makes it sound nice. Usually, that’s when I hear the essence again. And if I notice that my tinkering is only making this essence weaker, it’s time to call it quits and live with the remaining ‘imperfections.’ The mix is done.