9. Balancing Gamification Legal Risks and Business Opportunities

Nike has also successfully embraced gamification to attract and retain new customers. In 2010, Nike developed an app called Nike+ which allows runners to track their runs and monitor their results over time. In addition to tracking their steps, calorie burn, distances, and duration, users can compare themselves against their friends, and stay motivated with virtual competitions, mid-run cheers, trophies, medals, “attaboys,” and congratulatory messages from sporting icons like Lance Armstrong. Players can also participate in a game of Nike+ Tag. Runners compete against each other, and whoever runs the slowest or the shortest distance is designated as “it.” Here, gamification is a win-win: for the user, it encourages exercise and a healthy lifestyle; for the company, it creates customer loyalty and more sales of sneakers, accessories and the $1.99 app itself.

Gamification strategies have garnered considerable (and growing) interest across industries—and for good reason. Indeed, according to a recent Gartner report, by 2015, more than 50 percent of organizations that manage innovation processes will gamify those processes.1 Further, by 2014, “a gamified service for consumer goods marketing and customer retention will become as important as Facebook, eBay or Amazon, and more than 70 percent of Global 2000 organizations will have at least one gamified application.”2 Some reports also indicate that by 2016, worldwide corporate spending on gamification projects will grow to as much as $2.8 billion, from $100 million in 2011.3

The fundamental principles behind why gamification works so well to influence user behavior are hardly a recent phenomenon. Consider frequent flyer points, for example. Applying the dynamics and mechanics of gamification to social media interactions (on web and mobile sites) might very well revolutionize how business is conducted. Like all business applications of new technologies, although this explosion in gamification may be heralded as a good thing, there are nevertheless important legal risks to consider.

Although this explosion in gamification may be heralded as a good thing, there are nevertheless important legal risks to consider.

By no means intended as an exhaustive study of the topic, this chapter will discuss several unique legal issues encountered when gamification is employed as a marketing technique. In particular, the FTC Act and Endorsement Guides (regarding deceptive advertisement and “expert”-badge endorsements), the legal status (and regulation) of virtual goods and currencies, and federal privacy regulations (regarding collection and use of precise geolocation data collected) are examined. Prudence dictates carefully identifying and weighing potential legal risks and striking a balance between them and the gains which gamification can win for your business.

Unfair and Deceptive Marketing Practices

Like all marketing campaigns, those employing gamification techniques must avoid running afoul of Section 5 of the FTC Act, which prohibits deceptive acts and practices in advertising.4 To be found deceptive, three elements must be shown:

• There must be a representation, omission, or practice that is likely to mislead the consumer.

• The act or practice must be evaluated from the perspective of a reasonable consumer (which, in the case of communications targeted to children, means from the standpoint of an ordinary child or teenager).

• The representation, omission, or practice must be material—that is, likely to affect the consumer’s purchasing decision.5

The recent Complaint and Request for FTC investigation brought against PepsiCo and Frito-Lay by a consumer advocacy group illustrates the unique dangers involved when gamification techniques are employed in a company’s marketing initiatives.6

Beginning in 2008, PepsiCo’s subsidiary Frito-Lay, through its alias Snack Strong Productions (SSP), developed innovative marketing campaigns to sell more Doritos chips, including through its Hotel 626 and Asylum 626 online promotional games. In Hotel 626, players were trapped inside a haunted hotel, and could escape only by successfully completing 10 challenges, “each of which involves its own creepy, unique task or puzzle.”7 Players were encouraged to use their webcams, microphones, and mobile phones to make their escape. To increase the scare factor, the hotel was only open at dark, from 6 p.m. to 6 a.m. Players were allowed to explore the hotel in full motion 3D graphics, similar to first-person shooter games. Players had to maneuver through creepy hallways, dodge a serial killer’s lair, and even sing a demon baby to sleep to reach safety.

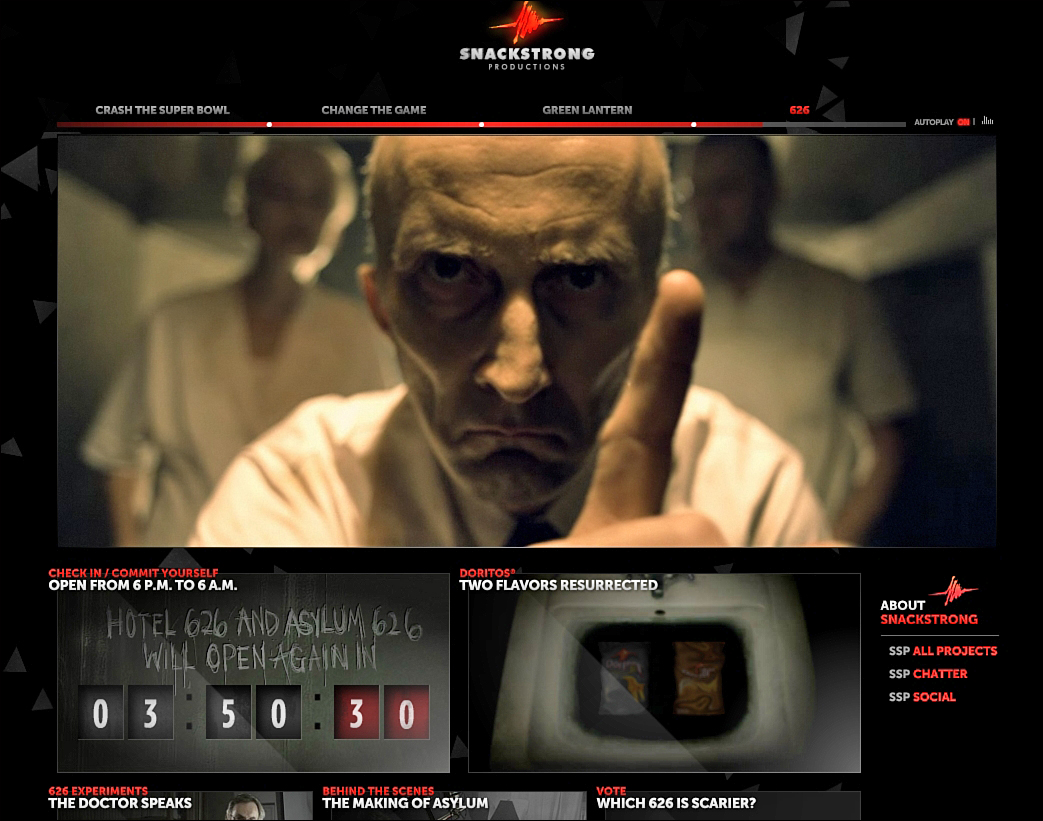

Remarkably, without showing a single corn chip or naming Doritos beyond the first screen, Hotel 626 had a major affect on sales, with more than two million bags sold in just 3 weeks after its launch in 2008.8 The success of Hotel 626 led to an even more terrifying campaign the following year, called Asylum 626 (see Figure 9.1)

Figure 9.1 The mad doctor examines you in the insane asylum.

Like its predecessor, Asylum 626 was only open at dark, between the hours of 6 p.m. and 6 a.m. This time, players “awaken to find themselves strapped to a bed in an insane asylum, held hostage at the mercy of a mad doctor.”9 To escape from the asylum, players had to “dodge lobotomy tools, electroshock therapy and crazed patients.”10

Asylum 626 also employed head-tracking technology, which allowed viewers to control the action using their webcams (by literally moving their heads to avoid an attack or waiving their hands to dodge a chainsaw, for example). The player’s webcam was used to project his or her image into the game. For example, players may see a reflection of their face in some water and the murderer standing behind them.

Players of Asylum 626 were also encouraged to allow access to their Facebook and Twitter accounts. The game generated tweets and Facebook posts designed to appear as if they come directly from the player, asking the player’s followers and friends to participate. The player’s Facebook friends were invited to save the player by screaming into their microphones or hitting as many keys on their keyboards as possible to distract the assailant.11 Players were also presented with photos of two of their Facebook friends and forced to “sacrifice one of these people to the murderer.”12 Facebook updates were also sent “to let the world know your choice.”13

The game abruptly stopped just as it reached its climactic final scene. To continue, players were told that they must buy a bag of Doritos Black Pepper Jack or Smoking Cheddar BBQ (the two flavors “brought back from the dead”) and use the infrared marker on the bag to unlock the ending.14 If players did not make the purchase, they were unable to complete the game.

It is reported that in the first four months following the release of Asylum 626, Frito-Lay had 850,000 visitors to the Asylum 626 website, received 18,000 Twitter mentions, and sold approximately five million bags of Doritos.15

Despite the tremendous success of these SSP campaigns, Pepsi Co and Frito-Lay became the target of an FTC complaint for unfair and deceptive marketing practices based on a report that found teens uniquely susceptible to the techniques employed by SSP, such as the following:

• “Augmented reality, online gaming, virtual environments, and other immersive techniques that can induce ‘flow,’ reduce conscious attention to marketing techniques, and foster impulsive behaviors”

• “Social media techniques that include surveillance of users’ online behaviors without notification, as well as viral brand promotion”

• “Data collection and behavioral profiling designed to deliver personalized marketing to individuals without sufficient user knowledge or control”

• “Location targeting and mobile marketing, techniques that follow young peoples’ movements and are able to link point of influence to point of purchase”

• “Neuromarketing, which employs neuroscience methods to develop digital marketing techniques designed to trigger subconscious, emotional arousal.”16

The complaint alleges that Pepsi Company’s Frito-Lay’s SSP promotions are deceptive acts or practices in violation of the Section 5 of the FTC Act in at least three ways:

• Disguising its marketing campaigns as entertaining video games and other “immersive” experiences, thus making it more difficult for teens to recognize such content as advertising

• Claiming to protect teens’ privacy while collecting and using various forms of personal information without meaningful notice and consent

• Using viral marketing techniques that violate the FTC Endorsement Guidelines

It is important to note that the underlying complaint is not a lawsuit, but a request for investigation (albeit the first of its kind filed with the FTC regarding digital marketing to teens). Whether the FTC will find Frito-Lay’s techniques deceptive is still an open question. Nevertheless, companies should take note to avoid the following:

• Disguising advertisements as entertainment, including using fake media and immersive marketing (and other forms of augmented reality) to promote campaigns, particularly those targeting children

• Engaging in viral marketing where recommendations and other communications appear to be from friends when they are not (for example, Facebook postings made without the explicit knowledge or consent of the sender by definition do not honestly reflect the views of the game player, and should therefore be avoided)

• Requesting contact information without adequately disclosing that it will be used for marketing purposes, or otherwise acting inconsistently with your company’s privacy policy.

![]() Note

Note

Whenever marketing to children is involved, companies should also take care to observe COPPA (as discussed in Chapter 7, “The Law of Social Advertising”)—or risk significant penalties. In United States v. Playdom, Inc.,17 for example, the operators of 20 online virtual worlds agreed to pay $3 million as part of settlement that they illegally collected and disclosed children’s information, in violation of COPPA.

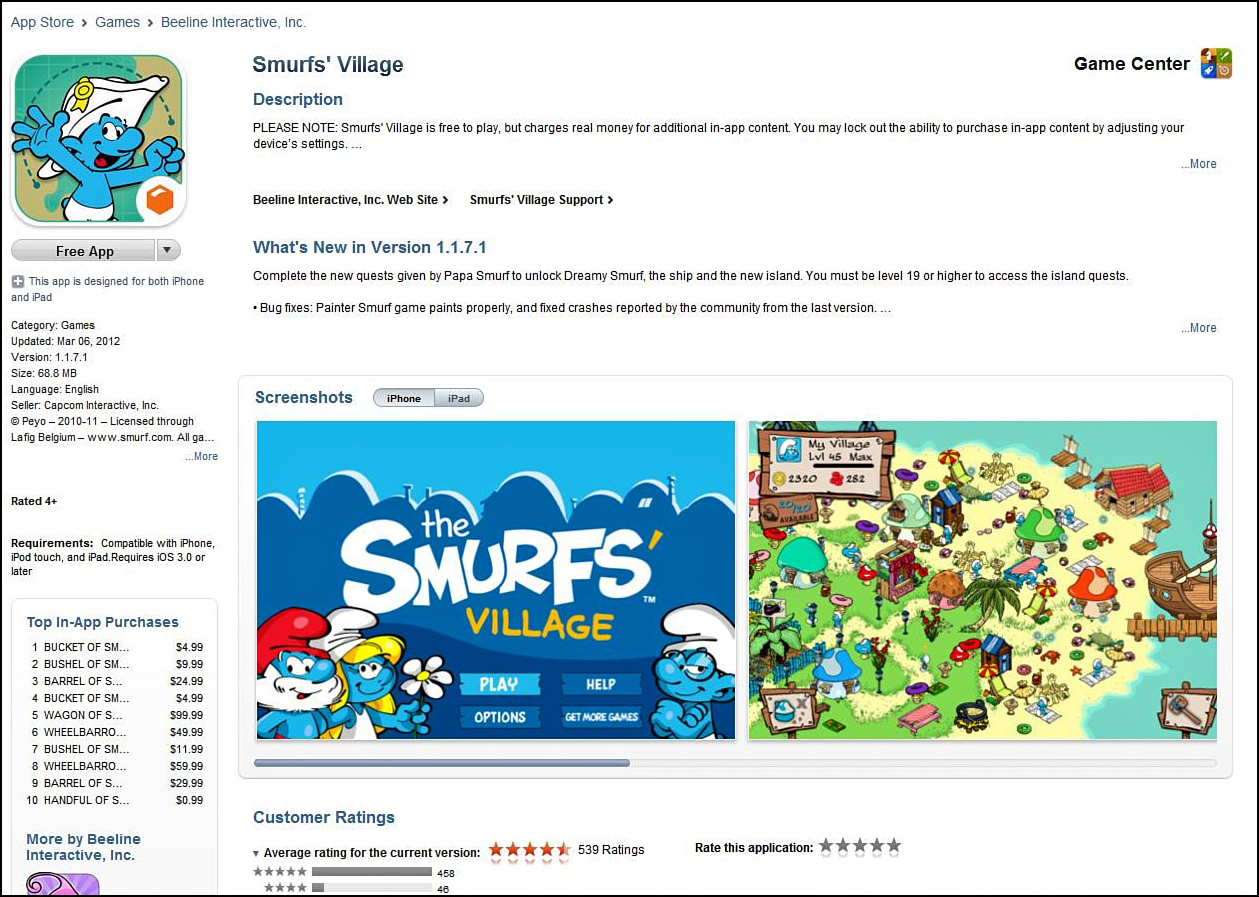

The consolidated class-action suit against Apple, In re Apple In-App Purchase Litigation,18 offers additional cautionary guidance when employing gamification techniques directed toward children. In this case, the class-action plaintiffs sued Apple for selling In-App Purchases (that is, virtual supplies, ammunition, fruits and vegetables, cash, and other fake “game currency”) within the game to advance or speed up game play, without the parents’ knowledge or consent. In the app Smurfs’ Village, for example, players are encouraged to buy Smurfberries to expedite the construction of the village. Smurfberries are sold in units of 50 (for $4.99) and 1,000 (for $59), generating (according to the complaint) approximately $4 million per month in sales. One 8-year-old reportedly racked up $1,400 in in-app purchased Smurfberries.

(In light of numerous public complaints and an FTC investigation, Smurfs’ Village has apparently updated its download screen to provide an in-app purchase warning—see Figure 9.2.)

Figure 9.2 Smurfs’ Village app warns that it charges “real money for additional in-app content” and provides instructions regarding how to “lock out” this ability on your device.

Whether Apple’s alleged bait-and-switch tactics will result in liability has yet to be established. (As of this writing, the cases are still pending.) Nonetheless, whenever virtual currencies are offered for sale, companies should take care to make prominent disclosures, both at the time of purchase and upon download of the “free” app, and should require affirmative consent (via password reentry, for example) for all individual sales transactions.

FTC Guidelines on Endorsements

As discussed in Chapter 2 (“Online Endorsements and Testimonials: What Companies and Their Employees Can and Cannot Tweet, Blog, or Say”), the 2009 Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Endorsement Guides19 cover consumer testimonials, such as reviews or recommendations endorsing a product, on any social media site. Under the FTC Endorsement Guides, the endorser needs to disclose the connection between the endorser and the advertiser, if the endorser is given anything of value for the endorsement. In other words, promotional strategies inducing third-parties to say positive things (via free goods, points, badges, and so on) should be disclosed by the endorser and through the companies’ promotional policies and literature.

For example, if a blogger gets a free video game in exchange for evaluating and reviewing the game, he must clearly and conspicuously disclose that he received the game free of charge.20 Likewise, if someone receives redeemable points each time he or she tells friends about a product, this fact needs to be clearly and conspicuously disclosed.21

![]() Note

Note

In one recent case,22 the FTC charged a PR firm with a violation of the FTC Act after its employees took to the iTunes store and other social media sites to promote video games developed by companies it represented. The employees’ posts, such as “Amazing new game” and “Really Cool Game,” failed to disclose that the posters were employed by the PR firm. According to the FTC, such tactics constituted unfair or deceptive acts or practices and unfair methods of competition in violation of the FTC Act.

There are additional considerations to be aware of in the case of experts. Social media strategies increasingly award “expert” badges as an incentive for consumers to frequently write positive reviews of a company’s products and service. However, if an advertisement portrays an endorser as an expert, the endorser’s qualifications must in fact give the endorser the expertise that he or she is represented as possessing.23 Leaderboards, badges, and expert labels all implicate truth-in-advertisement issues (and FTC enforcement actions) to the extent that such labels imply an expert status that the user does not actually possess with respect to the endorsed product.

Legal Status of Virtual Goods

Gamification relies heavily upon “virtual goods,” which generally refers to both “virtual items” and “virtual currencies.”

Like all “virtual goods,” virtual items are intangible objects purchased for use in online communities and games, mobile applications, and social networks. Virtual items can take on many forms, including: points, tokens, badges, rewards, mayorships, discounts, credits, golden tickets, avatars, and even “Smurfberries.”

Virtual currency is used for a variety of reasons, including as a mechanism for exchange (in the case of virtual worlds), for purchase of in-game virtual goods that enhance game play (in the case of gaming), and for the purchase of points that enhance status and prestige (for social networking sites).

As a business model, virtual goods enjoy several distinct advantages:

• Direct Monetization—Revenue comes directly from users, and not from ads, customer data, or other indirect sources.

• Profitability—As the costs to make virtual goods are low, the profit margins associated with the sale of virtual goods are relatively high.

• Engagement—Users who purchase virtual goods are invested. They have a reason to return to your site, and to encourage others to visit your site as well. This creates customer loyalty and brand virality.

In light of these benefits, it is little wonder that the sale of virtual goods is a highly lucrative industry. Indeed, PlaySpan, the Visa-owned Monetization-as-a-Service provider released a report in early 2012 that found, among other things, that consumer spending on virtual goods has almost doubled in two years, from $1.8 billion in 2009 to $2.3 billion in 2011.24

Despite the ubiquity of virtual goods, their exact legal status is not precisely defined. (As usual, the law lags behind the technological times.) The key debate is whether virtual goods are ‘goods’ (that is, property) or whether they are services (like entertainment) or something else. If virtual goods are property, then who owns them? Are they to be taxed? Are they subject to revenue-recognition reporting obligations? Can they be transferred? Can they be redeemed for the equivalent real monetary value in real cash? Can they be sold to third-parties?

If virtual goods are services, however, then presumably contract law—that is, th operator’s Terms of Service (TOS) or End-User License Agreement (EULA)—controls the relationship between the parties, and not property law.

While no court has yet provided a definitive answer to these questions (let alone one that can serve as precedent for jurisdictions outside from where it sits), there have been a rising number of cases in which such questions are implicated, from which guidance can be sought.

![]() Legal Insight

Legal Insight

A spotlight is put on the precarious legal status of “virtual goods” whenever a game using virtual goods announces that it is being discontinued, as users, who spent considerable money in purchasing these items, are being effectively told such goods will be of no use (value) anymore. Consider the example of ZipZapPlay, which discontinued its popular Facebook game “Baking Life” in early 2012 (see Figure 9.3).

Figure 9.3 Baking Life closes shop. Players’ “cash” no longer accepted at this “store.”

Baking Life, which allowed players to run a virtual bakery and make virtual “dough” (“money”) in the process, reportedly once attracted 6.7 million users per month, but closed shop in January 2012, despite having close to 760,000 average monthly customers.25

And what was to happen after closing day to any virtual goods and virtual currency (Zip Cash) that players had accumulated in the game? That was to be lost. (Although ZipZapPlay may accept the currency for use in its other games, it does not appear that it is legally required to do so.)

Baking Life’s Terms of Services26 provides that:

• All virtual currency and virtual items are the property of ZipZapPlay

• All virtual currency and virtual items are for the user’s personal and non-commercial use

• All virtual currency and virtual items are for use in the Baking Life app only and they are not transferable between or among different ZipZapPlay games and applications

• All purchases of virtual items and virtual currency are final and non-refundable

• All virtual currency and virtual items are not transferable or redeemable for any sum of money or monetary value from ZipZapPlay or any third party

• The user has no right or title to or interest in any virtual currency or virtual items earned or purchased by him or her

In the event that virtual goods are deemed not to be property (such that the TOS controls), players buying virtual goods in games that are later discontinued may simply be out of luck (and legal recourse).

For example, in 2006, Marc Bragg brought a lawsuit27 against Linden Labs, the developer of Second Life (the popular, massively multiplayer online role-playing game) (MMOG) for terminating his Second Life account, and seizing all of his in-game assets, including virtual land and other items (valued at between $4,000 and $6,000) and approximately $2,000 in real-world money on account. Linden Labs disabled Bragg’s account when it discovered that he had allegedly purchased virtual land at lower than market prices through a loophole in an auction system, in violation of Linden Labs’ Terms of Service. (The case ultimately settled.)

On April 15, 2010, Linden Labs found itself again the target of a lawsuit—Evans et al. v. Linden Research, Inc., et al.28—with the issue of virtual goods in play. According to the complaint, the defendants made false representations as part of a national campaign to induce individuals to visit the Second Life website and purchase virtual property. In particular, users were repeatedly told that they retained/obtained ownership rights to the land they purchased and retained all intellectual property right for any virtual items or content they created. Despite these representations, the defendants unilaterally changed the terms of its service agreement to state that these land and property owners no longer owned what they had created, bought, and paid for, but instead merely had a limited license to use them. Further, the plaintiffs’ accounts were terminated, and their virtual property was taken from them without compensation by the defendants.

![]() Note

Note

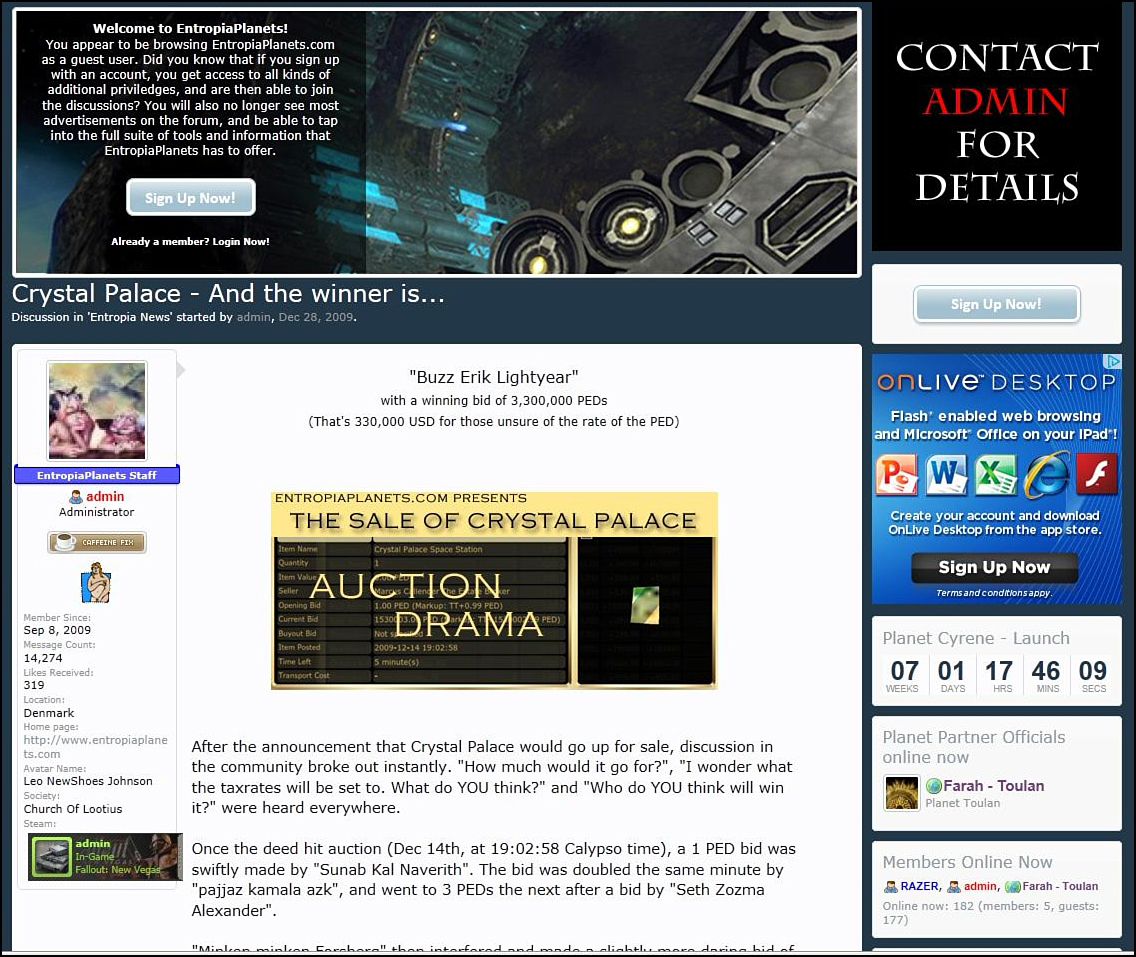

Although a Second Life participant’s goods are virtual, they are valuable property in the real world, which can be sold, licensed, or transferred both directly online and through third-party sites (such as eBay.com). The worldwide market for virtual properties, both virtual land and goods, is estimated in the billions.29 Indeed, MMOG Entropia Universe entered the Guinness Book of World Records in 2009 for the most expensive virtual world objects ever sold—a virtual space station (called Crystal Palace), for which the “owner” paid $330,000 real U.S. dollars. (See Figure 9.4.) Fast forward a few years later, and the record for the most expensive virtual property ever bought now belongs to SEE Virtual Worlds, which reportedly paid $6 million U.S. in order to acquire the virtual property Planet Calypso within Entropia Universe.

Figure 9.4 This dedicated player paid 3,300,000 PEDs—or $330,000 real U.S. dollars—to own a virtual Crystal Palace.

As of this writing, Evans et al. v. Linden Research, Inc., et al. is still pending in a federal district court in California. While it’s possible that the court may decide the case on different grounds (or that the case may settle), a court decision firmly addressing the legal status of virtual goods would have a profound impact on the gaming and gamification industry. Rather than relying upon their Terms of Service and End-User License Agreements to regulate their relationship with their users, businesses offering virtual goods may be required to honor greater property rights that users may have in these goods (particularly if they make representations elsewhere regarding the “rights” users have in these goods). Until courts provide a definitive resolution of this issue, businesses must operate with a certain degree of legal uncertainty. To hedge their bets, however, businesses that sell or interact with virtual goods should avoid making any representations that in-game goods are “property” that “belong” to their users.

The Credit CARD Act of 2009

As noted earlier, virtual currency is a gaming and gamification staple, and comes in the form of points, coins, redeemable coupons, store credit, and so forth. Because these forms of virtual currencies often operate like gift certificates (in that they are issued to be redeemed at a later date), they may be subject to both state and federal gift card regulations.

On the federal law front, the Credit Card Accountability Responsibility and Disclosure Act of 2009 (Credit CARD Act of 2009)30 protects consumers from unfair credit card billing practices. This Act also establishes guidelines for gift certificates, store gift cards, and general-use prepaid cards, which are collectively defined to include cards, electronic promises, payment codes and other devices, and include virtual currencies.31

Title 4 of the Credit CARD Act (which amends the Electronic Funds Transfer Act [EFTA]) prohibits retailers from:

• Setting expiration dates less than 5 years after the card, code, or device is sold or issued.32

• Charging dormancy, inactivity, and service fees unless the card, code or device has not been used for at least 12 months.33 If fees are charged after this period, retailers cannot assess more than one fee per month under any circumstances.34 Clear and conspicuous disclosures are required before purchase if card, code, or device is assessed fees or if they expire.35

The majority of states have also enacted their own laws applicable to gift cards.37 Such laws either restrict the circumstances under which dormancy, inactivity, or service fees may be charged or restrict the circumstances under which the card or funds underlying the card may expire. Other states simply require the disclosure of fees or expiration dates.

Perhaps as a precursor to an impending wave of gamification-based lawsuits, the first CARD Act litigation (Ferreira v. Groupon Inc., Nordstrom, Inc.38) was filed on January 21, 2011, against Groupon, a web-based company that offers discounted deals to consumers if they agree to purchase a specified number of groupons for a particular Daily Deal (the product or service that is being offered for sale that day).

This class-action lawsuit includes all consumers nationwide who purchased or acquired gift certificates (groupons) for products and services with expiration dates of less than 5 years from the date of purchase. The defendant retail class comprises all persons or entities that contract and/or participate with Groupon to promote their products and/or services using Groupon gift certificates with expiration dates. According to the complaint, groupons are gift certificates as defined under the CARD Act, and selling them with expiration dates is prohibited under the Act.

![]() Note

Note

Even apparently small matters can have large consequences. In Ferreira v. Groupon, the individually named plaintiff allegedly paid $25 to Groupon on November 21, 2010, in exchange for a $50 Groupon gift certificate redeemable at Nordstrom. The gift certificate expired on December 31, 2010, before Mr. Ferreira could redeem it.

Other Little-Known Laws Relating to Virtual Currencies

Virtual currencies are potentially subject to a wide variety of laws that prudent businesses transacting in virtual goods would be wise to consider.

For example, in certain circumstances, the offering of virtual currencies may trigger state money transmitter laws. These laws, typically enforced by a state’s department of financial institutions, generally regulate businesses that provide money transfer services or payment instruments, such as those offered by Western Union or PayPal.

Most money transmitter laws require that the money transmitter maintain a state license, post a surety bond (ranging from $25,000 to more than $1 million), and maintain a minimum net worth (ranging from $5,000 to $100,000).

In the case of virtual currencies, these laws may be most applicable when the virtual currency can be redeemed for real cash through third parties or transferred between users. Failure to comply with money transmitter laws can result in both civil and criminal penalties.

Further, many states have applied unclaimed property or escheat laws (that is, laws which require merchants to pay the value of any unused gift cards to the state if the card owner dies without heirs) to funds remaining on gift cards. Some states also require that consumers have the option of receiving cash back when the underlying balance falls below a certain amount. Whenever virtual currency is involved, therefore, these specific state law variables will need to be factored in, as well.

Finally, conversion between in-game and real-world currency may constitute virtual winnings, subject to federal and state gambling laws. In circumstances where real-world transactions for in-game assets are not permitted, but there is an unofficial secondary market, care must be taken to ensure that the rewards given do not have monetary value, perhaps by demonstrating enforcement of a company’s terms of service prohibiting secondary markets.

Location-Based Services

By leveraging social media technologies (such as tweeting and blogging) with geolocation data and game dynamics/mechanics, business can promote their products like never before. Given the technological advances over the past few years, behavioral targeting is expected to explode. Behavioral targeting is defined as the leveraging of social history data (where you are and what you are doing at any given time).

Despite the significant business value of leveraging real-time consumer data, companies need to be mindful of privacy issues regarding recording, storing, handling, and transferring geolocation data without the owner’s consent or knowledge.

Indeed, a wave of class-action lawsuits have been filed against Apple and many makers of popular mobile apps for allegedly unlawfully tracking users and sending their geolocation data history to advertisers.

For example, in In re iPhone/iPad Application Consumer Privacy Litigation,39 the class action plaintiffs allege that Apple’s unique device IDs (UDIDs)—the globally unique number assigned to each user’s iPhone, iPod touch, or iPad—capture users’ location and usage patterns (such as when and how long apps are used). The suit alleges that the UDID also captures other identifying information (such as the users’ real name or user ID and the time-stamped IP address and GPS coordinates). The suit further claims that such information is being shared with third-party ad networks without the users’ knowledge or consent.

According to the complaint, most users are unaware of the UDIDs on their iPhones and other Apple devices and cannot disable the UDID or prevent UDID information from being transferred. In addition, the complaint alleges that some app makers are selling additional information to ad networks, including user location, age, gender, income, sexual orientation, ethnicity, and political affiliation, without the users’ prior knowledge or consent. The plaintiffs sought an injunction against future unauthorized tracking, as well as damages under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act,40 the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986,41 and state consumer protection laws.

On September 20, 2011, the case was dismissed42 (without prejudice to re-file) because the plaintiffs were found to lack Article III standing—that is, the legal right to bring a claim based on a concrete (actual, not hypothetical) and particularized (personal and individual) injury.43 Finding that the plaintiffs’ failed to demonstrate how the defendants’ alleged conduct harmed them, the court rejected the plaintiffs’ argument that personal data has economic value that is somehow lost or diminished when shared for advertising or analytics purposes.

![]() Note

Note

Following the district court’s ruling in In re iPhone/iPad Application Consumer Privacy Litigation, several other courts similarly ruled that the unauthorized collection of personal information is not by itself sufficient to confer Article III standing. For example, in Del Vecchio v. Amazon.com Inc.,44 a federal district court in Washington rejected plaintiffs’ claim that Amazon’s harvesting of user data without their consent (which allegedly deprived them of “the opportunity to exchange their valuable information”), constituted Article III standing. The court found this theory to be “entirely speculative” because, “[w]hile it may be theoretically possible that Plaintiffs’ information could lose value as a result of its collection and use by Defendant, Plaintiffs do not plead any facts from which the Court can reasonably infer that such devaluation occurred in this case.”45

Similarly, in Low v. LinkedIn Corp.,46 a California district court held that allegations that LinkedIn permitted third parties to track plaintiffs’ online browsing history “without the compensation to which [plaintiff] was due” were “too abstract and hypothetical to support Article III standing.”47

On November 22, 2011, in a bid to cure these deficiencies, the plaintiffs filed an amended complaint, alleging the following harm (and presumed standing):

• The alleged collection of data “consumed portions” of the “memory on their devices,” and the iPhones’ bandwidth and battery life were also diminished as a result of Apple storing their location information without permission.

• Plaintiffs would have paid less for an iPhone had they known of its true nature.

• Plaintiffs “lost and have not been compensated for the value” of their data.

• The data had inherent value that the plaintiffs were entitled to exploit.

On January 10, 2012, the defendants filed another motion to dismiss, which (as of the time of this writing) is still pending before the court. Whether plaintiffs’ reformulation of harm will be sufficient to confer standing remains to be seen.

Regardless of the outcome, the case is still highly instructive. First, it reminds plaintiffs of their need to show specific injuries arising from specific acts caused by specific defendants; it is not enough to simply allege harm to consumers at large. Further, In re iPhone/iPad Application Consumer Privacy Litigation serves as a clarion call to companies that their data collection and privacy practices are under increasingly aggressive legal scrutiny.

Designing a Precise Geolocation Data Security Plan

Section 5 of the FTC Act grants the FTC broad enforcement authority to protect consumers from unfair trade practices, including in how companies handle consumers’ personal data. Companies handling consumers’ geolocation data are not exempt from the FTC’s reach, and should therefore adopt and enforce a comprehensive security plan to protect such data and to notify consumers when such data is lost or stolen.

Given that the tracking, storage, and sharing of precise geolocation information is becoming increasingly subject to legal and regulatory challenge, companies should establish compliance frameworks regarding how they will handle precise geolocation (PGL) data. At a minimum, the comprehensive PGL data security plan should include the following provisions:

• Program implementation and oversight: Companies should designate one or more senior-level employees to maintain and enforce a comprehensive PGL data security plan. The company’s plan should be in writing.

• Notice and choice: Companies should clearly and conspicuously provide consumers a choice as to whether they want their PGL data collected. With respect to social media services, if consumer information will be conveyed to a third-party app developer, the notice-and-choice mechanism should appear at the time the consumer is deciding whether to use the application and, in any event, before the application obtains the consumer’s PGL information. Companies involved in information collection and sharing on mobile devices (for example, carriers, operating system vendors, applications, and advertisers) should provide meaningful choice mechanisms for consumers and clearly and conspicuously inform consumers that their PGL data is being shared with advertisers or other third parties.

• Security policies: Companies should create policies governing whether and how employees keep, access, and transport records containing PGL data. Companies should also impose disciplinary measures for violations of its comprehensive PGL data security plan.

• Limited access: Companies should impose reasonable restrictions upon physical and electronic access to records containing PGL information. Terminated employees’ physical and electronic access to records containing PGL data should be immediately blocked, including deactivating their passwords and usernames.

• Disposal procedures: Companies should retain personal information no longer than reasonably necessary. Companies should have in place disposal procedures to properly delete or destroy PGL data after it is no longer necessary (from a legal and business perspective) to maintain.

• Monitoring and updating: Companies should regularly monitor and update the PGL data security plan to ensure its proper operation and effectiveness, particularly in light of ever changing security threats and technology.

• Security breaches: Companies should document responsive actions taken in connection with any incident involving a security breach. The plan should address what happens if PGL data is lost, stolen, or misused, and should detail who is to be alerted and what steps are to be taken to mitigate further damage.

• Employee training: Companies should educate and train their employees on the proper use of and the importance of PGL data information security. Employee access to PGL data of the employee’s customers should be limited to on a need to know basis.

The laws governing gamification are still relatively in their infancy (at least as applied to this new technology). Nonetheless, there are practical steps business can take to mitigate their legal exposure. To balance the business gains of gamification against the corresponding business risks, companies should observe the best practices summarized in Figure 9.5.

Figure 9.5 Legal Tips for Social Media Gamification.

Chapter 9 Endnotes

1 http://www.gartner.com/it/page.jsp?id=1629214

2 Id.

3 See Gamification Vendor Survey Results - Fall 2011(M2 Research), available at http://www.m2research.com/.

4 15 U.S.C. §45

5 Cliffdale Associates, Inc., 103 F.T.C. 110, 170–71 (1984)

6 Complaint and Request for Investigation of PepsiCo’s and Frito-Lay’s Deceptive Practices in Marketing Doritos to Adolescents (filed on Oct. 19, 2011), available at http://case-studies.digitalads.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/complaint.pdf

7 Hotel 626: The Online Haunted House, Facebook, http://www.facebook.com/pages/Hotel-626-The-Online-Haunted-House/179823455397906?sk=info

8 Kevin Ritchie, “Doritos Continues Interactive Horror Franchise with Asylum 626,” Boards Magazine (Sept. 22, 2009), available at http://www.boardsmag.com/articles/online/20090922/asylum626.html

9 Id.

10 “Doritos / Hotel 626,” Contagious, available at http://www.contagiousmagazine.com/2009/09/doritos_5.php

11 Kevin Ritchie, “Doritos Continues Interactive Horror Franchise with Asylum 626,” Boards Magazine (Sept. 22, 2009), available at http://www.boardsmag.com/articles/online/20090922/asylum626.html

12 The BuzzBubble Interviews Jeff Goodby, available at http://case-studies.digitalads.org/ftc-complaint/

13 Asylum 626 Case Study Video, available at http://case-studies.digitalads.org/ftc-complaint/

14 Kevin Ritchie, “Doritos Continues Interactive Horror Franchise with Asylum 626,” Boards Magazine (Sept. 22, 2009), available at http://www.boardsmag.com/articles/online/20090922/asylum626.html

15 Asylum 626 Case Study Video, available at http://case-studies.digitalads.org/ftc-complaint/

16 Complaint and Request for Investigation of PepsiCo’s and Frito-Lay’s Deceptive Practices in Marketing Doritos to Adolescents (filed on Oct. 19, 2011), available at http://case-studies.digitalads.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/complaint.pdf

17 United States v. Playdom, Inc., Case No. 8:11-CV-00724-AG-AN (C.D. Cal., filed May 11, 2011). You can find a copy of the consent decree and order at http://www.ftc.gov/os/caselist/1023036/110512playdomconsentorder.pdf.

18 In Re Apple In-App Purchase Litigation, Case No. 5:11-CV-1758 JF (N.D. Cal. Jun. 16, 2011)

19 16 C.F.R. § 255 et seq., Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising

20 16 C.F.R. § 255.5 (Example 7)

21 16 C.F.R. § 255.5 (Example 9)

22 In the Matter of Reverb Communications, Inc. et al., FTC File No. 092 3199 (Nov. 26, 2010). A copy of complaint is available at http://www.ftc.gov/os/caselist/0923199/101126reverbcmpt.pdf.

23 16 C.F.R. § 255.3

24 See PlaySpan’s Virtual Goods Trends Report (Feb. 29, 2012), available at http://www.slideshare.net/robblewis/playspan-magid-virtual-goods-report

25 http://www.eurogamer.net/articles/2012-01-20-popcap-to-shut-down-baking-life

26 http://www.zipzapplay.com/terms.html

27 Bragg v. Linden Research, Inc. et al., Case No. 2:06-CV-04925-ER (E.D. Penn. 2006), removed from Pennsylvania state court (Civil Action No. 06-08711) (Ct. Com. Pl. Chester County Pa. Oct. 4, 2006) in October 2006

28 Evans et al v. Linden Research, Inc., et al., Case No. 2:10-CV-1679-ER (E.D. Penn. Apr. 15, 2010); case subsequently transferred to U.S. District Court, Northern District of California, Case No. 4:11-CV-01078-DMR (N.D. Cal. Mar. 8, 2011)

29 http://mashable.com/2011/10/14/social-gaming-economics-infographic/

30 The Credit Card Accountability Responsibility and Disclosure Act of 2009, Public Law 111-24, 123 Stat. 1734 (2009)

31 15 U.S.C. § 1693l–1(a)(2)(A)-(C)

32 15 U.S.C. § 1693l–1(c)

33 15 U.S.C. § 1693l–1(b)

34 15 U.S.C. § 1693l–1(b)(2)(C)

35 15 U.S.C. §§ 1693l–1(b)(2)(B) and 1693l–1(c)(2)

36 15 U.S.C. § 1693l–1(a)(2)(D)

37 For a representative list of state gift card consumer protection laws, see http://www.consumersunion.org/pub/core_financial_services/003889.html.

38 Ferreira v. Groupon Inc., Nordstrom, Inc., Case No. 3:11-CV-0132-DMS-RBB (S.D. Cal. Jan. 21, 2011)

39 In re iPhone/iPad Application Consumer Privacy Litigation, Case No. 5:11-MD-02250-LHK (N.D. Cal. Aug. 25, 2011) (consolidated cases)

40 18 U.S.C. § 1030, which makes it unlawful to intentionally accesses a computer used for interstate commerce or communication without authorization, or in excess of authorization, and thereby obtain information

41 18 U.S.C. § 2520, which provides a civil cause of action to “any person whose wire, oral, or electronic communications is intercepted, disclosed, or intentional used” in violation of the ECPA

42 Order Granting Defendants’ Motions to Dismiss for Lack of Article III Standing with Leave to Amend (Document No. 8) (Sept. 20, 2011) in In Re iPhone/iPad Application Consumer Privacy Litigation, Case No. 5:11-MD-02250-LHK (N.D. Cal. Aug. 25, 2011)

43 A plaintiff must meet a number of requirements to have his/her case heard in federal court, including Article III of the United States Constitution which provides, among other matters, that “The Judicial Power shall extend to all Cases ...[and] to Controversies....” To satisfy Article III, a plaintiff “must show that (1) it has suffered an ‘injury in fact’ that is (a) concrete and particularized and (b) actual or imminent, not conjectural or hypothetical; (2) the injury is fairly traceable to the challenged action of the defendant; and (3) it is likely, as opposed to merely speculative, that the injury will be redressed by a favorable decision.” Friends of the Earth, Inc. v. Laidlaw Envtl. Sys. (TOC), Inc., 528 U.S. 167, 180-81 (2000).

44 Del Vecchio et al. v. Amazon.com Inc., Case No. 2:11-CV-00366-RSL (W.D. Wash. Mar. 2, 2011)

45 See Order Granting Defendant’s Motion to Dismiss (Document No. 58) (Dec. 1, 2011), in Del Vecchio et al. v. Amazon.com Inc., Case No. 2:11-CV-00366-RSL (W.D. Wash. Mar. 2, 2011).

46 Low v. LinkedIn Corp., Case No. 5:11-CV-01468-LHK (N.D. Mar. 25, 2011) (N.D. Cal. Nov. 11, 2011)

47 See Order Granting Defendant’s Motion to Dismiss (Document No. 28) (Nov. 11, 2011), in Low v. LinkedIn Corp., Case No. 5:11-CV-01468-LHK (N.D. Mar. 25, 2011)