7. The Law of Social Advertising

All social media advertising, regardless of platform, is governed by the same laws, policies, and ethics which govern the advertising industry as a whole. Practitioners who engage in social media promotions and advertising, therefore, need to be aware of, and operate within these legal constraints.

Despite the wide range of social media advertising techniques, common threads bind them together. First, they are all designed to capture leads (that is, to acquire friends, followers, subscribers, email addresses, and the like), convert them into sales (that is, to migrate audiences from social platforms into, and through the conversion funnel), and cultivate a cadre of brand evangelists. Further, all social media advertising, regardless of platform, is governed by the same laws, policies, and ethics which govern the advertising industry as a whole. Practitioners who engage in social media promotions and advertising, therefore, need to be aware of, and operate within these legal constraints.

In addition to the rules governing online sweepstakes and promotions (discussed in Chapter 1), online endorsements and testimonials (discussed in Chapter 2), web host immunity under the Communications Decency Act (CDA) (discussed in Chapter 6), and data privacy and security (discussed in Chapter 10), this chapter highlights a few more key laws impacting social media advertising, and provides best practice tips for businesses using social media advertisements. In particular, this chapter examines the FTC Act (regarding false advertising vis-à-vis consumers); section 43 of the Lanham Act (regarding false advertising vis-à-vis business competitors); the CAN-SPAM Act of 2003 (regarding electronic solicitations); and the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) (regarding advertising and other business practices directed toward children).

This chapter does not discuss all the laws and regulations impacting social media advertising, as such a discussion would be beyond the intended scope of this book. The reader should note, however, that there are many laws and regulations with are potentially implicated in this space, including those relating to pricing, use of the terms “free” and “rebate,” guarantees and warranties, “Made in the U.S.A.” labels, telemarketing, mail orders, group-specific target marketing (for example, senior citizens, Hispanic citizens), advertising in specific industries (for example, food, alcohol, medical products, funeral, jewelry, motor vehicles, retail food stores, and drugs), and labeling (for example, clothing, appliances, cosmetics, drugs, food, furs, hazardous materials, and tires).

The FTC Act

As discussed in Chapter 2, advertisements are principally governed by Section 5 of the FTC Act1 (and the associated regulations promulgated under FTC’s authority) (and the corresponding state “mini-FTC Acts”2), which generally requires that advertisements be truthful, non-deceptive, adequately substantiated, and not be unfair.

Section 5 of the FTC Act prohibits “unfair or deceptive acts or practices” affecting commerce. “Unfair” practices are those that cause or are “likely to cause substantial injury to consumers which [are] not reasonably avoidable by consumers themselves and not outweighed by countervailing benefits to consumers or to competition.”3

In determining whether a particular advertisement (or other business practice) is unfair or deceptive for Section 5 purposes, courts generally consider the following factors:

• Whether the representation or omission is likely to mislead the consumer

• The reasonableness of the consumer’s reaction to the representation or omission, determined from the total impression the advertisement creates in the mind of the consumer, not by isolating words or phrases within the advertisement

• The materiality of the representation or omission in terms of whether it is “likely to affect the consumer’s conduct or decision with regard to a product or service.” If inaccurate or omitted information is material, consumer injury is likely (and in many instances presumed), because consumers are likely to have chosen differently but for the deception.

Best Practices for Social Media Advertising

At a minimum, businesses advertising via social media should therefore observe the following required (and best) practices:

• Be truthful in your social media advertising—Any claims that you make, through social media or otherwise, must be truthful. A false ad for purposes of Section 5 is one which is “misleading in a material respect.”4 Businesses should be mindful not only of the honesty of their own practices, but of the practices of those whom they rely on to spread their advertising message on their behalf—including outside ad agencies, PR and marketing firms, affiliate marketers, and so on.

• Make sure your social media advertising claims aren’t unfair or deceptive—To comply with the FTC Act, advertisements also need to be fair and non-deceptive. Examples of misleading or deceptive practices include “false oral or written representations, misleading price claims, sales of hazardous or systematically defective products or services without adequate disclosures, failure to disclose information regarding pyramid sales, use of bait and switch techniques, failure to perform promised services, and failure to meet warranty obligations.”5

Similarly, the FTC considers the following factors in assessing whether an advertisement is unfair:

• Whether the practice injures consumers

• Whether it violates established public policy

• Whether it’s unethical or unscrupulous6

Examples of unfair practices include withholding or failing to generate critical price or performance data, for example, leaving buyers with insufficient information for informed comparisons; and exercising undue influence over highly susceptible classes of purchasers, as by promoting fraudulent “cures” to seriously ill cancer patients.7

• Substantiate your social media advertising claims (and those made on your behalf)—For social media advertisements (like advertisements in traditional media), it is incumbent upon the advertiser to have adequate substantiation of all claims (both expressed and implied) depicted in the ad—that is, advertisers must have a reasonable basis for advertising claims before they are disseminated.8 It is important to note that companies may face liability not only for the unsubstantiated claims they make, but also for claims made on their behalf, including by sponsored endorsers, such as the blogger in the following example (even though she was not paid for her review):

Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act

While the FCT Act governs advertiser liability to consumers for false or misleading advertising, advertisers may equally face liability to business competitors under Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act10 for such conduct. The Lanham Act—a piece of federal legislation that governs trademark law in the U.S., and which prohibits trademark infringement, trademark dilution, and false advertising—defines false advertising as “any false designation of origin, false or misleading description of fact, or false or misleading representation of fact, which...in commercial advertising or promotion, misrepresents the nature, characteristics, qualities, or geographic origin of his or her or another person’s goods, services, or commercial activities.”

In order to establish a claim of false or misleading advertising under the Lanham Act, a plaintiff must prove that:

• The defendant made a false or misleading statement of fact about its or plaintiff’s products or services

• The false or misleading statement actually deceived or tended to deceive a substantial portion of the intended audience

• The statement is material in that it will likely influence the deceived customer’s purchasing decision

• The defendant has been or is likely to be injured as a result of the false statement, either by direct diversion of sales from itself to defendant or by a loss of goodwill associated with its products or services.

• The advertisements were introduced into interstate commerce.

![]() Note

Note

With literally false statements, the plaintiff need not prove that the audience is actually deceived or is likely to be deceived by the literally false representation. The law presumes that a literally false advertisement deceives the intended audience. In the case of claims that are literally true but misleading (that is, claims that prove misleading, in the overall context of the advertisement, because they convey a false impression or fail to disclose important qualifying information), the plaintiff is required to prove that the challenged statement actually deceived (or tends to deceive) the intended audience.

Doctor’s Assocs., Inc. v. QIP Holders, LLC.11 is one of the first cases brought under the Lanham Act relating to social media and user-generated content (UGC) comparative advertisement marketing campaigns. In 2006, the operators of the Subway sandwich chain sued the operators of the Quiznos sandwich chain over certain UGC advertisements created as part of a nationwide contest called “Quiznos v. Subway TV Ad Challenge.” In this contest, Quiznos encouraged contestants to upload videos to a dedicated site comparing a Subway sandwich to the Quiznos Prime Rib Cheesesteak sandwich using the theme “meat, no meat.” Predictably, videos unfavorable to Subway were submitted.

Subway sued Quiznos, claiming that the contestant-created entries contained false and misleading advertising in violation of the Lanham Act, among other laws.

Although the videos at issue were not directly created by Subway, the court denied Quiznos’ motion for summary judgment, finding that Quiznos could be found to have actively participated in the creation or development of the submitted UGC.12 The case shortly settled after this ruling. (The implications of this case on the scope of immunity under the Communications Decency Act—which generally protects hosts from liability for the content that others post on their site—are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 6.)

Although the settlement prevented further development of the law relating to false advertising claims and UGC marketing messages, the case underscores the fact that advertisers could potentially face liability from competitors if false or misleading advertising claims are distributed through social media channels.

Indeed, on August 2, 2010, Ocean Spray Cranberries, Inc. filed a lawsuit against, amongst others, Decas Cranberry Products, Inc., alleging that Decas orchestrated “an unlawful and malicious campaign” against Ocean Spray designed to harm the company’s reputation, frustrate its relationships with its customers, and undermine its dealings with grower-owners and other cranberry growers in the industry.13

The complaint alleged violations of the Agricultural Fair Practices Act, Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act, and the Massachusetts Unfair and Deceptive Trade Practices Act.

According to Ocean Spray’s complaint, Decas used a variety of methods to disseminate its “smear campaign,” including widely distributed letters and emails, internet blogs and websites, Facebook accounts, YouTube videos and Twitter postings, which falsely accused Ocean Spray of the following:

• Creating “a significant oversupply of cranberries” in the industry and contributing to that surplus by reducing the amount of cranberries in its products

• Mislabeling its Choice® sweetened dried cranberry product, a lower-cost alternative for industrial customers, and harming the cranberry industry by selling a product that takes fewer barrels of cranberries to create

• Harming the industry and “abandoning the cranberry,” and of introducing Choice solely for “corporate greed” and with a “blind focus on profits.”

• Producing the Choice product for its own corporate profit, and that the “favorable return” relating to Choice is only for Ocean Spray, and not for its “growers”

Allegedly, these same representations were variously repeated on a YouTube video called “The Scamberry” (see Figure 7.1), as well as on a Twitter account called @Scamberry and a Facebook page called Scamberry (allegedly created by “Michele Young,” who posed as a “consumer advocate”).

Figure 7.1 A YouTube video on “Scamberry” channel discussing Ocean Spray.

The case settled on December 12, 2011. Although the settlement denied us an important legal precedent regarding the interplay between social media and Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act, the case further highlights the need for companies to tread carefully when making claims about their competitors in any medium.

Northern Star Industries, Inc., v. Douglas Dynamics LLC14 is another new media case involving false advertising, and apparently provides the first instance in which a party was ordered to use social media to remedy a social media advertising “wrong.”

In 2011, Northern Star, the manufacturer of “Boss” brand snow plows, filed suit against its direct competitor, Douglas Dynamics, the manufacturer of “Fisher” and “Western” brand snowplows. According to the complaint, Douglas Dynamics conducted an advertising campaign (via print, video, web, and social media) which made false comparisons between the two company’s products, including:

• A print ad (appearing in stand-alone and print-based media) showing a photograph of a man with a bloody face holding a piece of raw meat against an eye, and another of a shattered windshield, both stating, “IF YOUR V-PLOW DOESN’T COME WITH A TRIP EDGE, IT BETTER COME WITH A CRASH HELMET.”

• Another ad containing a large headline stating, “IF YOUR V-PLOW ISN’T A WESTERN, YOU MAY NEED TO GET YOUR HEAD EXAMINED,” combined with a picture of a doctor reviewing two skull x-rays (one with a fracture and with “Boss” written on it in stylized letters), a statement that with [Northern Star’s] V-plow trip blades “you’ll experience bone-jarring windshield-banging, steering wheel smacking wake up calls with every obstacle you encounter,” and a statement that the Western snow plow is “just what the doctor ordered.”

• A video link page stating “If your V-plow has a trip blade, you know the story. There you are, plowing along, feeling good, saving the rest of the world from the storm, when BAM you’re in the crash zone wondering what the #@!* you hit. That’s because when a trip blade hits a hidden obstacle in vee or scoop, it can’t trip. And the results aren’t pretty. Good thing FISHER® XtremeV™ V-plow comes with a trip edge, which trips over hidden obstacles in any configuration. It can save you a lot of headaches.”

Douglas Dynamics published these allegedly false and misleading print ads (and links) on its Fisher and Western Facebook pages.

On January 26, 2012, the court granted Northern’s Star request for a preliminary injunction, preliminarily finding that, amongst other matters, Douglas Dynamics’ claims—implying and/or stating that users of Northern Star’s blade-trip plows will be physically injured but users of Fisher/Western edge-trip plows will not—were not true.15

After giving the parties a chance to agree upon a proposed order, on February 15, 2012 the court ordered Douglas Dynamics to publicly withdraw such claims. Of particular interest, Douglas Dynamics was ordered to post a retraction notice on its Fisher/Western Facebook pages and various industry blogs, for one year. See Figure 7.2.

Figure 7.2 Retraction posted by Douglas Dynamics on its Fisher Facebook page, as ordered by the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Wisconsin.

The Northern Star decision reminds advertisers that, while the legal standards expressly governing social media marketing are relatively in their infancy, advertisers using social media must still comply with existing laws governing traditional models of advertising. As the law catches up with the technology, it is safe to say that existing legal framework will continue to be asked to absorb, accommodate, and proscribe new methods of advertising.

The CAN-SPAM Act of 2003

The Controlling the Assault of Non-Solicited Pornography and Marketing Act of 2003 (CAN-SPAM Act)16 establishes the United States’ first national standards for the sending of commercial email, provides recipients the right to opt out of future emails, and imposes tough penalties for violations.

The CAN-SPAM Act makes it “unlawful for any person to initiate the transmission, to a protected computer, of a commercial electronic mail message, or a transaction or relationship message, that contains, or is accompanied by, header information that is materially false or materially misleading.”17 An electronic mail message is defined as “a message that is sent to a unique electronic mail address,”18 and an electronic mail address means a “destination, commonly expressed as a string of characters, consisting of a unique user name or mailbox and a reference to an Internet domain (commonly referred to as a ‘domain part’), whether or not displayed, to which an electronic mail message can be sent or delivered.”19

Despite its name, the CAN-SPAM Act does not apply only to bulk email; it also covers all commercial electronic messages, which the law defines as “any electronic mail message the primary purpose of which is the commercial advertisement or promotion of a commercial product or service (including content on an Internet website operated for a commercial purpose).”20 Both business-to-business and business-to-consumer email must comply with the law, as must commercial solicitations transmitted through social media sites.

On March 28, 2011, in Facebook, Inc. v. MaxBounty, Inc.,21 the Ninth Circuit District Court held that unwanted commercial solicitations transmitted through Facebook to friends’ walls, news feeds, inboxes, or external email addresses registered with Facebook are electronic messages subject to the requirements of the CAN-SPAM Act. In this case, Facebook alleged that MaxBounty created fake Facebook pages intended to redirect unsuspecting Facebook users to third-party commercial sites through a registration process that required a Facebook user to become a fan of the page and to invite all of his or her Facebook friends to join the page. The invitations were then routed to the user’s wall, the news feeds, or home pages of the user’s friends, Facebook inboxes of the user’s friends, or external email addresses. Adopting an expansive interpretation of the scope of the CAN-SPAM Act, the court concluded that these communications were electronic messages and, therefore, subject to the Act’s restrictions.

![]() Note

Note

In a subsequent motion to dismiss filed in the case,22 the court held that a user who violates Facebook’s terms of service may thereby violate the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA),23 on the theory that the user exceeded his or her “authorized access” to the site. By the same logic, therefore, a CFAA violation (and the resulting civil and criminal penalties) may be triggered anytime a user violates any website’s terms of service, not just Facebook’s, and obtains anything of value.

The Ninth Circuit’s holding in Facebook, Inc. v. MaxBounty is consistent with the rulings of other courts refusing to limit the reach of the CAN-SPAM Act to traditional email messages.24 In MySpace v. The Globe.Com, Inc.,25 for example, a California District Court observed that the “overarching intent of this legislation is to safeguard the convenience and efficiency of the electronic messaging system, and to curtail overburdening of the system’s infrastructure.” The court concluded that limiting “the protection to only electronic mail that falls within the narrow confines set forth by Defendant does little to promote the Congress’s overarching intent in enacting CAN-SPAM.”26

To be safe, particularly in light of the severe civil and criminal penalties for violations of the statute,27 all social network messages that are commercial in nature, whether submitted by an advertiser or by a consumer who has been induced by the advertiser to send a message, should be considered electronic communications subject to the CAN-SPAM Act.

In determining whether an online message is subject to the CAN-SPAM Act, regard must be paid to the primary purpose of the message. If the message contains only commercial content, its primary purpose is commercial, and it must comply with the requirements of the CAN-SPAM Act. If it contains only transactional or relationship28 content (for instance, content that facilitates an already agreed-upon transaction or updates a customer about an ongoing transaction), its primary purpose is transactional or relationship. In that case, it is exempt from most provisions of the CAN-SPAM Act, although it may not contain false or misleading routing information.

![]() Note

Note

If the message combines commercial content and transactional or relationship content, the primary purpose of the message is decided by a reasonableness test. If a recipient reasonably interpreting the subject line would likely conclude that the message contains an advertisement or promotion for a commercial product or service, the primary purpose of the message is commercial. Likewise, if the majority of the transactional or relationship part of the message does not appear at the beginning of the message, it is a commercial message under the CAN-SPAM Act.

Commercial electronic messages must adhere to the following CAN-SPAM Act requirements:

• The message cannot contain header information that is materially false or misleading. Your From, To, Reply-To, and routing information—including the originating email address, domain name, or IP address—must be accurate and identify the person or business who initiated the message.29

• The message cannot contain deceptive subject headings. The subject heading must accurately reflect the contents or subject matter of the message.30

• The message must clearly and conspicuously identify that the message is an advertisement or solicitation.31

• The message must provide a valid physical postal address of the sender.32

• The message must include a clear and conspicuous explanation of how the recipient can opt out of getting future emails from the sender.33

• The sender must be able to process opt-out requests for at least 30 days after it sends the message,34 and it must honor the opt-out requests within 10 business days.35

Although the Facebook, Inc. v. MaxBounty court did not give any guidance as how to achieve compliance with CAN-SPAM Act with respect to Facebook transmissions like wall postings, messages, and news feed updates, best practices include, at a minimum, identifying the communication as an advertisement and providing an opt-out option for future messages. In light of the Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) increased enforcement actions against violators of the CAN-SPAM Act, those who use social media to send what have now been defined as electronic mail messages without complying with the Act’s requirements do so at their own peril.

The Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA)

Companies using social media in advertising campaigns (or for other business purposes) should also be aware of legal restrictions on their privacy and data security practices as regards to minors.

The COPPA Rule,36 issued pursuant to the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA),37 imposes certain requirements on operators of websites or online services directed to children under 13 years of age, and on operators of other websites or online services that have actual knowledge that they are collecting personal information online from a child under 13 (collectively, operators). The Rule became effective on April 21, 2000.

![]() Note

Note

Some sites obviously target children (for example, games, cartoons, school-age educational material). Nonetheless, operators of websites publishing content that may attract children also need to observe COPPA. Whether a website is directed to children under 13 is determined objectively based on whether the site’s subject matter and language are child-oriented, whether advertising appearing on the site targets children, or whether the site uses animated characters, famous teen idols, or other similar kid-friendly devices. Simply stating that your site is not directed to children under 13 is insufficient to achieve COPPA immunity.

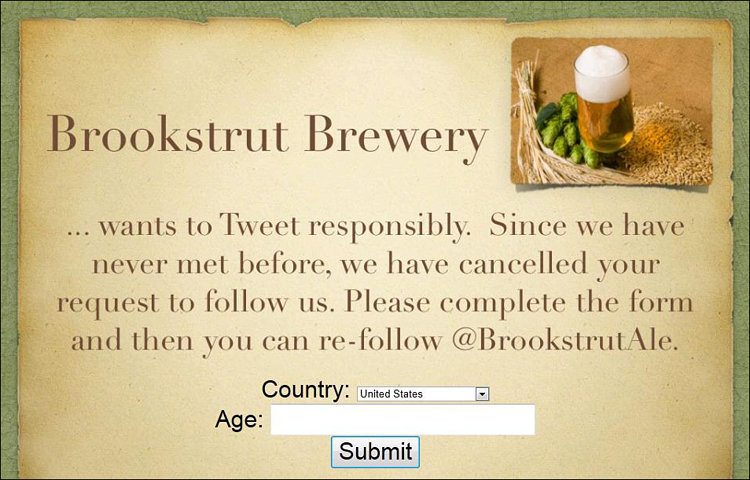

Further, while not necessarily required by COPPA, companies which sell products not suitable for or legally available to minors (for example, alcohol or tobacco) have a separate set of legal obligations regarding restricting access to their web (and social media) sites. Various service providers are beginning to offer products to allow companies to restrict their marketing messages (and followers) to consumers above a certain age. For example, social relationship management platform company, Vitrue, created a fictitious Twitter account (@BrookstrutAle) to showcase its new “Twitter Gate” feature to screen followers (see Figure 7.3). After attempting to follow a brand, Twitter Gate sends a direct message to the would-be follower: “We only allow people who are of legal drinking age to follow us. Please click this link to verify your age: pub.vitrue.com/kFH.” The link in turn brings you to a page where the consumer’s age can be verified.

Figure 7.3 A fictitious Twitter account designed to showcase Vitrue’s “Twitter Gate.”

Among other things, the Rule requires operators to meet specific requirements prior to collecting, using, or disclosing personal information from children, including, but not limited to, the following:

• Post a privacy policy on the home page of its website or online service and a link to the privacy policy everywhere personal information from children is collected.38

• Provide notice to parents about the site’s information collection practices and, with some exceptions, obtain verifiable parental consent before collecting, using or disclosing personal information from children.39

• Give parents the choice to consent to the collection and use of a child’s personal information for internal use by the website or online service, and give them the chance to choose not to have that personal information disclosed to third parties.40

• Provide parents with reasonable access to their child’s information and the opportunity to delete the information and opt out of the future collection or use of the information.41

• Not condition a child’s participation in a game, the offering of a prize, or another activity on the disclosure of more personal information than is reasonably necessary to participate in the activity.42

• Establish and maintain reasonable procedures to protect the confidentiality, security and integrity of the personal information collected from children.43

Take care to design your age-collection input screen in a manner that does not encourage children to provide a false age to gain access to your site. Visitors should be asked to enter their age in a neutral, nonsuggestive manner. In particular, visitors should not be informed of adverse consequences prior to inputting their age (that is, that visitors under 13 cannot participate or need parental consent in order to participate), because this might simply result in untruthful entries. Cookies should also be used to prevent children from back-arrowing to enter a false age when they discover they do not qualify.

Neither COPPA nor the Rule defines online service, but it has been interpreted broadly to include any service available over the Internet or that connects to the Internet or a wide area network, including mobile applications that allow children to

• Play network connected games

• Engage in social networking activities

• Purchase goods or services online

• Receive behaviorally targeted advertisements

• Interact with other content or services44

Likewise, Internet-enabled gaming platforms, Voice over IP (VoIP) services, and Internet-enabled location-based services, are also online services covered by COPPA and the Rule.45 In addition, retailers’ premium texting and coupon texting programs that register users online and send text messages from the Internet to users’ mobile phone numbers are online services.46

COPPA Enforcement

The FTC has brought a number of cases alleging violations of COPPA in connection with social networking services, including the following:

• U.S. v. Sony BMG Music Entertainment:47 In this case, the FTC alleged that, through its music fan websites, Sony BMG Music Entertainment enabled children to create personal fan pages, review artists’ albums, upload photos or videos, post comments on message boards and in online forums, and engage in private messaging, in violation of COPPA. Sony BMG was fined $1 million in civil penalties.

• U.S. v. Industrious Kid, Inc.:48 In this case, Industrious Kid, Inc. was fined $130,000 for operating a web and blog-hosting service that permitted children to message, blog, and share pictures without first obtaining verifiable parental consent prior to collecting, using, or disclosing personal information from children online.

• U.S. v. Godwin (d/b/a skidekids.com):49 Skidekids, operator of self-proclaimed “Facebook and Myspace for Kids,” was fined $100,000 for obtaining children’s birth date, gender, username, password, and email without prior parental consent.

• U.S. v. Xanga.com, Inc.:50 Xanga.com, which provides free or premium log template software to its registered members and publishes the members’ blogs on the Internet, was fined $1 million in civil penalties for collecting date-of-birth information from users who indicated that they were under the age of 13.

On August 12, 2011, in its first case (U.S. v. W3 Innovations, LLC51) involving the applicability of COPPA to child-directed mobile apps (specifically games for the iPhone and iPod touch), the FTC filed a complaint against W3 Innovations, LLC. The FTC said W3 Innovations, a mobile app developer and owner, violated the COPPA Rule by illegally collecting and disclosing information from children under the age of 13 without their parents’ prior verifiable consent.

In its complaint, the FTC alleged that the defendants—owner Justin Maples and W3 Innovations, doing business as Broken Thumbs Apps—collected and permanently maintained more than 30,000 email addresses from users of their Emily’s Girl World and Emily’s Dress-Up apps. The apps also included features such as a blog, which invites users to post “shout-outs” to friends and family members, ask advice, share embarrassing “blush” stories, submit art and pet photographs, and write comments on blog entries that provided users the chance to freely post personal information.

According to the FTC, the defendants failed to provide notice of their information-collection practices and did not obtain verifiable consent from parents prior to collecting, using, or disclosing their children’s personal information, all in violation of the COPPA Rule.

The defendants agreed to pay a $50,000 civil penalty to settle the charges. The defendants further agreed to refrain from future violations of COPPA, agreed to delete all personal information collected and maintained in violation of the Rule, and consented to compliance monitoring for a 3-year period.

Best practices dictate that all websites post privacy policies regarding the website operator’s information practices. This is a requirement as it relates to collecting personally identifiable information from children under 13 years old. For such companies, their privacy policy should include the name, address, telephone number, and email address of each operator collecting or maintaining personal information from children through their sites; the types of personal information collected from children; and how that information is collected (for example, directly inputted, cookies, GUIDs, IP addresses).

The privacy policy also should detail how such personal information is or might be used, and it should explain whether such personal information is disclosed to third parties, providing parents the option to deny consent to disclosure of the collected information to third parties.

Finally, the policy should also state that the operator cannot condition a child’s participation in an activity on the disclosure of more information than is reasonably necessary to participate; that parents can access their child’s personal information to review or have the information deleted; and that parents have the opportunity to refuse to permit further use or collection of the child’s information.

Proposed Changes to COPPA

On September 15, 2011, in the face of rapid technological and marketing developments and the growing popularity of social networking and interactive gaming with children, the FTC announced proposed amendments to the COPPA Rule.52 The proposed changes, if adopted by the FTC, will profoundly impact websites and other online services, including mobile applications, that collect information from children under 13 years old, even if the operator merely prompts or encourages (versus requires) a child to provide such information.53

Definition Changes

The proposed amendment changes key definitions to information from children. The most important definitional changes are examined here:

• Personal information: The proposed amendment expands the definition of personal information to include IP addresses, geolocation information, screen names, instant messenger names, video chat names, and other usernames (even when not linked to an email address), and additional types of persistent identifiers (that is, codes and cookies that recognize specific IP addresses)—other than those collected solely for the purpose of internal operations—such as tracking cookies used for behavioral advertising. Accordingly, personal information includes not just personally identifiable information provided by a consumer, but information that identifies the user’s computer or mobile device. As an additional measure to avoid tracking children, and which would have far-reaching impact for many companies using social media contests and marketing, photographs, videos and audio files that contain a child’s image or voice may also be added to the definition of personal information because of the metadata (in particular, location data) that they store.

• Collection: The FTC proposes broadening its definition of collection to include circumstances both where an operator requires the personal information and when the operator merely prompts or encourages a child to provide such information. The revised definition also enables children to participate in interactive communities, without parental consent, provided that the operator takes reasonable measures to delete “all or virtually all” children’s personal information from a child’s postings before they are made public, and to delete it from its records.

• Online contact information: The FTC proposes expanding the definition of online contact information to encompass all identifiers that permit direct contact with a person online, including instant messaging user identifiers, VoIP identifiers, and video chat user identifiers.

![]() Legal Insight

Legal Insight

In its initial Request for Public Comment, the FTC noted that it sought public input on the implications for COPPA enforcement raised by technologies such as mobile communications, interactive television, interactive gaming, and other evolving media. In this regard, the FTC specifically requested comments on the terms website, website located on the Internet, and online services, which are used, but not defined, in COPPA and the Rule.

Following the initial comment period, the FTC found participant consensus that COPPA and the Rule are “written broadly enough to encompass many new technologies without the need for new statutory language.”54 Accordingly, the FTC concluded that online service is broad enough to “cover any service available over the Internet, or that connects to the Internet or a wide-area network.”55 The FTC further concluded that the term website located on the Internet, covers “content that users can access through a browser on an ordinary computer or mobile device.”56

In the FTC’s view, COPPA and the Rule apply to “mobile applications that allow children to play network-connected games, engage in social networking activities, purchase goods or services online, receive behaviorally targeted advertisements, or interact with other content or services.”57 Further, “Internet-enabled gaming platforms, voice-over–Internet protocol services, and Internet-enabled location-based services also are online services covered by COPPA and the Rule.”58

Parental Notice

COPPA currently requires that parents be notified via online notice and direct notice of an operator’s information-collection and information-use practices. The FTC proposes changes to both kinds of notice:

• On the operator’s website or online service (the online notice, usually in the form of a posted privacy policy): For online notice, the FTC would require that parental notification take place in “a succinct ‘just-in-time’ notice, and not just a privacy policy.” In other words, key information about an operator’s information practices would have to be presented in a link placed on the website’s home page and in close proximity to any requests for information.

• In a notice delivered directly to the parent whose child seeks to register on the site or service (the direct notice): For direct notice, the FTC would require operators to provide more detail about the personal information already collected from the child (for example, the parent’s online contact information either alone or together with the child’s online contact information); the purpose of the notification; action that the parents must or may take; and what use, if any, the operator will make of the personal information collected.

Parental Consent Mechanisms

The proposed Rule would also significantly change the mechanisms for obtaining verifiable parental consent before collecting children’s information. One such change eliminates the less-reliable “email plus” method of consent, which currently allows operators to obtain consent through an email to the parent, provided an additional verification step is taken, such as sending a delayed email confirmation to the parent after receiving consent. Instead, the proposed Rule provides for new measures to obtain verifiable parental consent, including consent by video conference, scanned signed parental consent forms, and use of government-issued identification, provided that the identification information is deleted immediately after consent is verified.

Confidentiality and Security Requirements

The FTC also proposes tightening the Rule’s current security and confidentiality requirements. In particular, operators of sites that collect children’s information would be required to ensure that:

• Any third parties receiving user information have reasonable security measures in place

• Collected information is retained for only as long as is reasonably necessary

• The information is properly and promptly deleted to guard against unauthorized access to, or use in connection with, its disposal.

![]() Note

Note

In February 2012, the FTC released a staff report—Mobile Apps for Kids Current Privacy Disclosures are DisAPPointing59—detailing its concerns regarding the privacy failures in many mobile apps directed towards children and with the lack of information available to parents prior to downloading such apps. According to the FTC, “[p]arents should be able to learn what information an app collects, how the information will be used, and with whom the information will be shared”—prior to download. The study recommends, among other steps, that App developers provide this information through simple and short disclosures or icons that are easy to find and understand on the small screen of a mobile device, and alert parents if the app connects with any social media, or allows targeted advertising to occur through the app. Connection to social media sites could pose a problem, because the terms of most social media sites, including Facebook, specifically prohibit access if the user is under 13. The report indicates that, in the coming months following the report’s release, the FTC “will conduct an additional review to determine whether there are COPPA violations and whether enforcement is appropriate.” In light of the FTC’s vigorous enforcement of COPPA and the Rule, app developers and other businesses which target children are reminded to have compliance measures in place prior to collecting personal information from children.

Safe Harbor Programs

The COPPA Rule encourages industry groups to create their own COPPA programs, seek FTC approval, and help website operators to comply with the Rule by using the programs (known as safe harbor programs). The FTC proposes strengthening its oversight of self-regulatory safe harbor programs by incorporating initial audits and annual reviews. Under the revised Rule, the FTC would also require industry groups seeking to create programs to verify their competence to create and oversee such programs, and it would require groups that run safe harbor programs to oversee their members.

The FTC’s proposed revisions are a means to catch the COPPA Rule up with evolving technologies. All entities operating websites or mobile games directed to children or websites or mobile games that are used by (or attract) children should be aware of the COPPA Rule and the FTC’s proposed changes. Noncompliance carries with it a very high price tag—up to $1,000 per violation (that is, per child), an amount that can rapidly balloon into hundreds of thousands of dollars (or more) for even a moderately popular website, mobile game, or app.

As of the date of publication, there are five safe harbor programs approved by the FTC. Generally speaking, operators that participate in a COPPA safe harbor program will be subject to the review and disciplinary procedures provided in the safe harbor’s guidelines in lieu of formal FTC investigation and law enforcement.

Currently, to be approved by the FTC, self-regulatory guidelines must: (1) require that participants in the safe harbor program implement substantially similar requirements that provide the same or greater protections for children as those contained in the Rule; (2) set forth an effective, mandatory mechanism for the independent assessment of safe harbor program participants’ compliance with the guidelines; and (3) provide effective incentives for safe harbor program participants’ compliance with such guidelines.60

On February 24, 2012, Aristotle International, Inc. became the fifth FTC-approved safe harbor program.61 Embracing new and evolving technologies, Aristotle’s safe harbor program allows participants to obtain parental consent throughhe “use of electronic real-time face-to-face verification”62 via Skype and similar video-conferencing technologies, and by e-mailing an electronically signed consent form along with a scanned copy of a government-issued identification document.

Summation

Ignoring the legal issues and lessons surrounding social media advertising is fraught with peril and can expose advertisers (and they brands they represent) to significant penalties. Businesses and their advertisers using social media would do well to heed the legal tips outlined in this chapter, and summarized in Figure 7.4.

Figure 7.4 Social Media Legal Tips for Advertising.

Chapter 7 Endnotes

1 15 U.S.C. §§ 45 and 52

2 A number of states have modeled their consumer protection statutes on the FTC Act. See, for example, California Unfair Competition Act, CAL. BUS. & PROF. CODE. § 17200; Connecticut Unfair Trade Practices Act, CONN. GEN. STAT. § 42-110b; Florida Deceptive and Unfair Trade Practices Act, FLA. STAT. § 501.204; Georgia Fair Business Practices Act, GA. CODE ANN. § 10-1-391; Hawaii’s Antitrust and Consumer Protection Laws, HAW. REV. STAT. § 480-2; Louisiana Unfair Trade Practices and Consumer Protection Law, LA. REV. STAT. ANN. §§ 51:1401-1426; Maine Unfair Trade Practices Act, ME. REV. STAT. tit. 5, §§ 207-214; Massachusetts Consumer Protection Act, MASS. GEN. LAWS ch. 93A § 2; Montana Unfair Trade Practices and Consumer Protection Act, MONT. CODE ANN. §§ 30-14-103 to -104; Nebraska Consumer Protection Act, NEB. REV. STAT. §§ 59-1601 to -1623; New York Consumer Protection Act, N.Y. GEN. BUS. LAW § 349; North Carolina Monopolies, Trusts and Consumer Protection Act, N.C. GEN. STAT. § 75-1.1; Ohio Consumer Sales Practices Act, OHIO REV. CODE ANN. § 1345.02; Rhode Island Deceptive Trade Practices Act, R.I. GEN. LAWS §§ 6-13.1-2 to .1-3; South Carolina Unfair Trade Practices Act, S.C. CODE ANN. § 39-5-20; Vermont Consumer Fraud Statute, VT. STAT. ANN. tit. 9, §§ 2451-2453; and Washington Consumer Protection Act, WASH. REV. CODE § 19.86.920.

3 15 U.S.C. § 45(n)

4 15 U.S.C. § 55(a)(1)

5 See FTC’s Policy Statement on Deception (Oct. 14, 1983), appended to Cliffdale Associates, Inc., 103 F.T.C. 110, 174 (1984), available at http://www.ftc.gov/bcp/policystmt/ad-decept.htm

6 See FTC’s FTC Policy Statement on Unfairness (Dec. 17, 1980), appended to International Harvester Co., 104 F.T.C. 949, 1070 (1984), available at http://www.ftc.gov/bcp/policystmt/ad-unfair.htm

7 Id.

8 See FTC’s Policy Statement Regarding Advertising Substantiation (Aug. 2, 1984), appended to Thompson Medical Co., 104 F.T.C. 648, 839 (1984), aff’d, 791 F.2d 189 (D.C. Cir. 1986), cert. denied, 479 U.S. 1086 (1987), available at http://www.ftc.gov/bcp/guides/ad3subst.htm

9 16 C.F.R. § 255.1 (Example 5)

10 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a)

11 Doctor’s Associates, Inc. v. QIP Holder LLC, et al., Case No. 3:06-CV-1710 (D. Conn.) (Oct. 27, 2006)

12 Doctor’s Associates, Inc. v. QIP Holder LLC, et al., Case No. 3:06-CV-1710 (D. Conn.) (Oct. 27, 2006) (Document 271) (Order denying defendants’ Motion for Summary Judgment entered Feb. 19, 2010)

13 Ocean Spray Cranberries, Inc. v. Decas Cranberry Prods., Inc., Case No. 1:10-CV-11288-RWZ. Mass.) (Aug. 2, 2010)

14 Northern Star Industries, Inc., V. Douglas Dynamics, LLC, Case No. 2:11-CV-1103-RTR (E.D. Wis.) (Dec. 5, 2011)

15 Northern Star Industries, Inc., V. Douglas Dynamics, LLC, Case No. 2:11-CV-1103-RTR (E.D. Wis.) (Jan. 26, 2012)(Document 38) (Decision and Order)

16 15 U.S.C. § 7701 et seq.

17 15 U.S.C § 7704(a)(1)

18 15 U.S.C. § 7702(6)

19 15 U.S.C. § 7702(5); MySpace v. Wallace, 498 F.Supp.2d 1293, 1300 (C.D. Cal. 2007)

20 15 U.S.C. § 7702(2)(A)

21 Facebook, Inc. v. MaxBounty, Inc., Case No. 5:10-CV-4712-JF, Order Granting in Part and Denying in Part Motion to Dismiss (Docket No. 35) (Mar. 28, 2011)

22 Facebook, Inc. v. MaxBounty, Inc., Case No. 5:10-CV-4712-JF, Order Denying Motion to Dismiss (Docket No. 46) (Sept. 14, 2011)

23 18 U.S.C. § 1030. See, in particular, § 1030(a)(4), which provides that “Whoever knowingly and with intent to defraud, accesses a protected computer without authorization, or exceeds authorized access, and by means of such conduct furthers the intended fraud and obtains anything of value, unless the object of the fraud and the thing obtained consists only of the use of the computer and the value of such use is not more than $5,000 in any 1 year period ... shall be punished as provided in subsection (c) of this section.”

24 See, for example, MySpace v. Wallace, 498 F.Supp.2d 1293, 1300 (C.D. Cal. 2007); see also MySpace v. The Globe.Com, Inc., 2007 WL 168696, at *4 (C.D. Cal. Feb. 27, 2007)

25 MySpace v. The Globe.Com, Inc., 2007 WL 168696 (C.D. Cal. Feb. 27, 2007)

26 Id., at *4

27 Each separate electronic message sent in violation of the CAN-SPAM Act is subject to penalties of up to $16,000. Further, the CAN-SPAM Act has certain aggravated violations that may give rise to additional civil and criminal penalties, including imprisonment.

28 The primary purpose of an email is transactional or relationship if it consists only of content that:

(i) Facilitates, completes, or confirms a commercial transaction that the recipient already has agreed to enter into with the sender

(ii) Provides warranty, product recall, safety, or security information about a product or service used or purchased by the recipient

(iii) Provides information about a change in terms or features or account balance information regarding a membership, subscription, account, loan or other ongoing commercial relationship

(iv) Provides information directly related to an employment relationship or employee benefit plan in which the recipient is currently participating or enrolled

or

(v) Delivers goods or services as part of a transaction that the recipient is entitled to receive under the terms of a preexisting agreement with the sender.

See 15 U.S.C. § 7702(17)(A)

29 15 U.S.C. § 7704(a)(1)

30 15 U.S.C. § 7704(a)(2)

31 15 U.S.C. § 7704(a)(5)(A)(i)

32 15 U.S.C. § 7704(a)(5)(A)(iii)

33 15 U.S.C. § 7704(a)(5)(A)(ii)

34 15 U.S.C. § 7704(a)(3)(A)(ii)

35 15 U.S.C. § 7704(a)(4)(A)

36 16 C.F.R. Part 312

37 15 U.S.C. § 6501 et seq.

38 16 C.F.R. §§ 312.4(b)

39 16 C.F.R. §§ 312.4(b) and 312.5

40 16 C.F.R. § 312.5

41 16 C.F.R. § 312.6

42 16 C.F.R. § 312.7

43 16 C.F.R. § 312.8

44 See the FTC’s Request for Public Comment to Its Proposed Amendments to COPPA, “COPPA Rule Review, 16 CFR Part 312, Project No. P-104503,” available at http://www.ftc.gov/os/2011/09/110915coppa.pdf

45 Id.

46 Id. (wherein the FTC stated, by way of example, that text alert coupon and notification services offered by retailers such as Target and JC Penney are online services)

47 U.S. v. Sony BMG Music Entertainment, Case No. 1:08-CV-10730 (S.D.N.Y, filed Dec. 10, 2008). You can find a copy of the consent decree and order at http://www.ftc.gov/os/caselist/0823071/081211consentp0823071.pdf.

48 U.S. v. Industrious Kid, Inc., Case No. 3:08-CV-0639 (N.D. Cal., filed Jan. 28, 2008). You can find a copy of the consent decree and order at http://www.ftc.gov/os/caselist/0723082/080730cons.pdf.

49 U.S. v. Godwin (d/b/a skidekids.com), Case No. 1:11-CV-03846-JOF (N.D. Ga., filed Nov. 8, 2011). You can find a copy of the consent decree and order at http://www.ftc.gov/os/caselist/1123033/111108skidekidsorder.pdf.

50 U.S. v. Xanga.com, Inc., Case No. 1:06-CV-6853-SH (S.D.N.Y., filed Sept. 7, 2006). You can find a copy of the consent decree and order at http://www.ftc.gov/os/caselist/0623073/xangaconsentdecree_image.pdf.

51 U.S. v. W3 Innovations LLC, Case No. CV-11-03958 (N.D. Cal., filed Aug. 12, 2011). You can find a copy of the consent decree and order at http://www.ftc.gov/os/caselist/1023251/110815w3order.pdf.

52 See Request for Public Comment to the Federal Trade Commission’s Proposed Amendments to COPPA, 76 FR 59804 (“COPPA Rule Review”) (Sept. 27, 2011), available at http://www.ftc.gov/os/2011/09/110915coppa.pdf.

53 The FTC accepted comments on the proposed amendments to the COPPA Rule until December 23, 2011.

54 See Request for Public Comment to the Federal Trade Commission’s Proposed Amendments to COPPA, 76 FR 59804, at 59807 (“COPPA Rule Review”) (Sept. 27, 2011), available at http://www.ftc.gov/os/2011/09/110915coppa.pdf.

55 Id.

56 Id.

57 Id.

58 Id.

59 See FTC’s Mobile Apps for Kids: Current Privacy Disclosures are DisAPPointing (Feb. 2012), available at http://www.ftc.gov/os/2012/02/120216mobile_apps_kids.pdf.

60 16 C.F.R. § 312.10(b)

61 See FTC’s Letter Approving Aristotle, Inc.’s Safe Harbor Program Application Under the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Rule (Feb. 24, 2012), available at http://www.ftc.gov/os/2012/02/120224aristotlecoppa.pdf.

62 See Revised Request for Safe Harbor Approval by the Federal Trade Commission for Aristotle International, Inc.’s Integrity Safe Harbor Compliance Program Under Section 312.10 of the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Rule, available at http://www.ftc.gov/os/2012/02/120224aristotleapplication.pdf.