3. The [Mis]Use of Social Media in Pre-Employment Screening

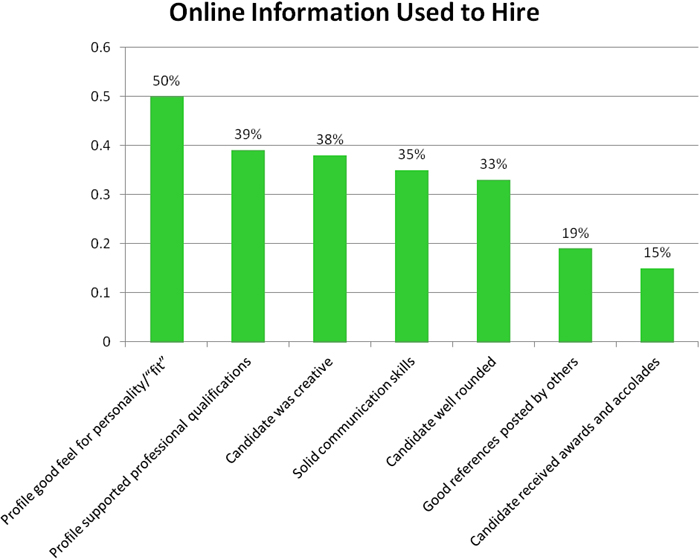

Likewise, according to a 2009 CareerBuilder Survey2 of more than 2,600 hiring managers:

• 18% surveyed reported that information online encouraged them to hire candidates (see Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1 Information found on social media sites sometimes leads employers to make job offers.

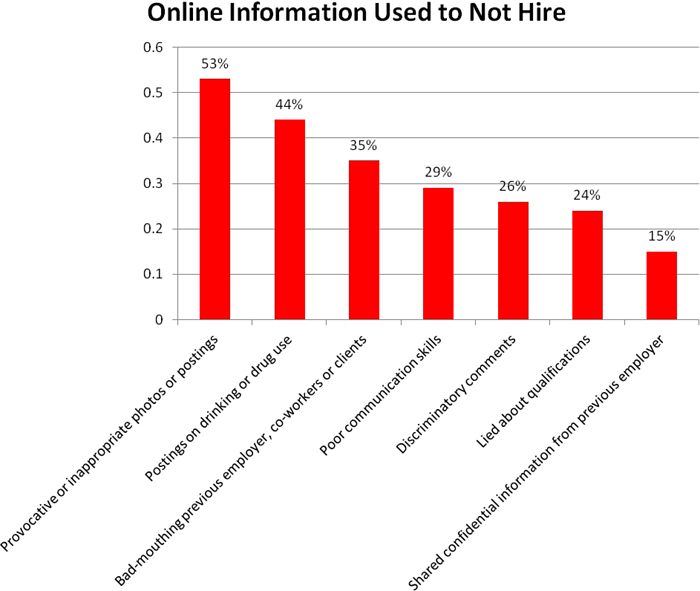

• 35% reported that information online led them to not hire candidates (see Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2 Conversely, information found online often leads to an applicant not getting hired.

For example, a prospective Cisco employee tweeted, “Cisco just offered me a job! Now I have to weigh the utility of a fatty paycheck against the daily commute to San Jose and hating the work.” Reportedly, a self-described Cisco “channel partner advocate” saw the tweet and responded, “Who is the hiring manager. I’m sure they would love to know that you will hate the work. We here at Cisco are versed in the web.” Clearly, this applicant failed to appreciate the not-so-“social” nature of her social media communications. Whether it was this tweet or something else that cost her the job, we may never know.

Clearly, this applicant failed to appreciate the not-so-“social” nature of her social media communications.

Although there are ample bona fide business reasons for the use of social media in pre-employment screening, potential pitfalls exist for such screening as well. These pitfalls include obtaining information that is unlawful to consider in any employment decision, such as the applicant’s race, religion, national origin, age, pregnancy status, marital status, disability, sexual orientation (some state and local jurisdictions), gender expression or identity (some state and local jurisdictions), and genetic information. Because this information is often prominently displayed on social networking profiles, even the most cautious employer may find itself an unwitting defendant in a lawsuit.

To minimize the likelihood of a charge of discrimination, employers should consider assigning a person not involved in the hiring process to review social media sites (pursuant to a standard written search policy), to filter out any information about membership in a protected class (that is, race, religion, and so on), and to only forward information that may be lawfully considered in the hiring process. Employers should keep records of information reviewed and used in any employment decision, and be sure that any information learned from social media sites in the employment decision process is used consistently.

![]() Note

Note

An employer who circumvents an applicant’s privacy settings on social media sites—by having a colleague “friend” the applicant for purposes of obtaining information they otherwise would not have access to, for example—might be exposing itself to a claim for invasion of privacy. To avoid this potential liability, employers should only view information that is readily accessible and intended for public viewing.

Employers should also familiarize themselves with the “off-duty” laws in each state where their employees are located and refrain from considering any protected activities in their hiring decisions. More than half of the states prohibit employers from taking an adverse employment action based on an employee’s lawful conduct on their own time (that is, off the job), even if (in many cases) the employee is only a prospective employee. In Minnesota, for example, it is unlawful for an employer to prohibit a prospective employee from using lawful consumable products, such as alcohol and tobacco, during nonworking hours.3 Further, New York protects all lawful recreational activities, including political activities, during nonworking hours.4

While employers can continue to use social media for recruiting purposes, they should take care not to violate existing laws in the hiring process (and be mindful of the various laws developing in this area as well).

The Fair Credit Reporting Act

Employers should also be alerted to the fact that pre-employment social media background checks—if not conducted correctly—might also give rise to liability under the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA),5 a federal law that protects the privacy and accuracy of the information in consumers’ credit reports.

Employment background checks routinely include information from a variety of sources: credit reports, employment and salary history, criminal records, and (with increasing frequency) social media. Companies providing background reports to employers—and employers using such reports—must comply with the FCRA. The FCRA delineates consumers’ rights as job applicants and employers’ responsibilities when using credit reports and other background information to assess an employment application. Although the FCRA might not come immediately to mind when considering social media background checks, the FRCA does govern consumer reports “used for the purpose of evaluating a consumer for employment, promotion, reassignment, or retention as an employee.”6

![]() Note

Note

The FCRA—and similar state consumer protections laws (for example, California Investigative Consumer Reporting Agencies Act)—needs to be observed whenever social media content is used as part of a company’s background check process. If your company uses a third party to collect information and provide it to you in a report, the FCRA is triggered. However, the FCRA does not apply if the company conducts the background screening entirely internally.

Before the FCRA was passed, little or no protection existed for job applicants who were denied employment or who were later fired because of false, inaccurate, incomplete, or irrelevant information contained in their consumers’ reports, which were (then lawfully) obtained without the employee’s knowledge or consent from private consumer reporting agencies. Congress enacted the FCRA to ensure that employment decisions, together with other matters (like extension of credit), are based on fair, accurate, and relevant consumer information.7

Under the FCRA, a consumer report is defined as any written, oral, or other communication of information provided by a consumer reporting agency bearing on a consumer’s creditworthiness (and other credit-related) matters and/or his or her “character, general reputation, personal characteristics, or mode of living which is used or expected to be used or collected in whole or in part for the purpose of serving as a factor in establishing the consumer’s eligibility for ... employment purposes.”8

A subclass of consumer reports, called investigative consumer reports, contains information obtained through personal interviews with friends, neighbors, associates, and acquaintances of the consumer concerning the consumer’s character, general reputation, personal characteristics, or mode of living.9

Both types of reports must be obtained through a consumer reporting agency (“CRA”), which is defined as “any person who regularly engages in whole or in part in the practice of assembling or evaluating consumer credit information or other information on consumers for the purpose of furnishing consumer reports to third parties.”10 To ensure the accountability of employers who use background information about their employees in making hiring, firing, or promotion decisions, employers must:

• Provide the applicant/employee with notice that a consumer report may be obtained, generally via a clear and conspicuous written disclosure to the consumer, found in a stand-alone document that consists solely of the disclosure,

• Obtain written authorization from the applicant/employee for the employer to obtain a consumer report for employment purposes, and

• Provide certain notices and certifications (detailed below) regarding the basis of any adverse employment decision.11

Although no court has yet squarely ruled on the issue, given the FCRA’s broad scope, and the expansive definitions of consumer reporting agency, consumer report, and investigative consumer report, it is almost inevitable that background checks utilizing profiles and information stored with social networking services will be held to fall within FCRA’s reach.

For companies that assemble reports about applicants based on social media content and regularly disseminate such reports to third parties (including affiliates), therefore, both the reporting company and the user of the report must ensure compliance with the FCRA, including the following provisions:

• Notice and authorization—An employer must get the applicant’s written permission before asking for a report about him/her from a CRA or any other company that provides background information. The employer has no further obligation to review the application if permission is withheld.12

It is almost inevitable that background checks utilizing profiles and information stored with social networking services will be held to fall within FCRA’s reach.

If an employer intends to use an investigative consumer report (that is, a consumer report based on personal interviews by the CRA) for employment purposes, the employer must disclose to the applicant that an investigative consumer report may be obtained, and the disclosure must be provided in a written notice that is mailed, or otherwise delivered, to the applicant no later than three days after the date on which the employer first requests the investigative consumer report.13 Further, the disclosure must also include a statement informing the applicant of his or her right to request additional disclosures of the “nature and scope” of the investigation.14 In this regard, the disclosure “must include a complete and accurate description of the types of questions asked, the types of persons interviewed, and the name and address of the investigating agency.”15

• Due diligence—The CRA or other company providing the background information must take reasonable steps to ensure the maximum possible accuracy of what’s reported (from social network sites or otherwise) and that it relates to the correct person.

• Pre-adverse action procedures—If an employer might use information from a credit or other background report to take an adverse action (for example, to deny your application for employment), the employer must give the applicant a copy of the report and a document called A Summary of Your Rights Under the Fair Credit Reporting Act before taking the adverse action.16 If any inaccurate or incomplete information is found in the report (for example, the report is for the wrong “John Smith”, contains a false driving or criminal record, or inaccurately lists salary, job titles, or employers), the job applicant is advised to contact the company that issued the report and dispute the information. Following an investigation, the CRA or other company providing background information must send an updated report to the employer if the applicant asks them to.

• Adverse action procedures—If an employer takes an adverse action against an applicant based on information in a report, it must provide the applicant with notice, which can be in writing or delivered orally or by electronic means.17 The notice must include the name, address, and phone number of the company that supplied the credit report or background information; a statement that the company that supplied the information did not make the decision to take the adverse action and cannot give the applicant any specific reasons for it; and a notice of the applicant’s right to dispute the accuracy or completeness of any information in the report and to get an additional free report from the company that supplied the credit or other background information if the applicant asks for it within 60 days after receipt of the notice.18

Under the FCRA, companies selling background reports for employment must require that employers certify to the CRA that the report will not be used in a way that would violate federal or state equal employment opportunity laws or regulations. In an effort to reduce the risk of inadvertent discrimination or allegations of discrimination, employers should also require that companies conducting social media background checks remove protected class information (for example, race, religion, disability) from any reports they generate.

Real-World Examples

There is a growing rise in legal and regulatory scrutiny regarding social media background checks. A few illustrative cases are discussed here.

FTC v. Social Intelligence Corp.

On May 9, 2011, the FTC’s Division of Privacy and Identity Protection sent a “no action” letter to Social Intelligence Corporation (“Social Intelligence”), “an Internet and social media background screening service used by employers in pre-employment background screening.”19 The FTC found that Social Intelligence is a consumer reporting agency “because it assembles or evaluates consumer report information that is furnished to third parties that use such information as a factor in establishing a consumer’s eligibility for employment.”20 The FTC stated that the same rules that apply to consumer reporting agencies—including, notably, the FCRA—apply equally in the context of social networking sites.

The FTC completed its investigation and found that no further action was warranted at that time, but that its decision should “not to be construed as a determination that a violation may not have occurred,” and that it “reserves the right to take further action as the public interest may require.”21

In a letter dated September 19, 2011, Senators Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn) and Al Franken (D-Minn) wrote to Social Intelligence expressing concern that the company’s “collection of online and social media information about job applicants and distribution of that information to potential employers may contain inaccurate information, invade consumers’ right to privacy online, violate the terms of service agreements of the websites from which your company culls data, and infringe upon intellectual property rights.” 22

The letter raises a series of questions, which should be considered by all businesses that provide, or request, social media background checks, including:

• “How does your company determine the accuracy of the information it provides to employers?”

• “Is your company able to determine whether information it finds on a website is parody, defamatory, or otherwise false?”

• “Is your company able to differentiate among applicants with common names?”

• “Search engines like Google often provide archived versions of websites; these cached web pages may contain false information that was later updated. Search engines also provide “mirrors” of websites, like Wikipedia or blog articles; these mirrored pages may be archives of inaccurate information that has since been corrected. Is your company able to determine whether information it is providing is derived from an archived version of an inaccurate website?”

• “Does your company specify to employers and/or job applicants where it searches for information—e.g., Facebook, Google, Twitter?”

• “Is the information that your company collects from social media websites like Facebook limited to information that can be seen by everyone, or does your company endeavor to access restricted information?”

• “There appears to be significant violations of user’s intellectual property rights to control the use of the content that your company collects and sells. .... These pictures [of the users], taken from sites like Flickr and Picasa, are often licensed by the owner for a narrow set of uses, such as noncommercial use only or a prohibition on derivative works. Does your company obtain permission from the owners of these pictures to use, sell, or modify them?”

FTC v. the Marketers of 6 Mobile Background Screening Apps

On January 25, 2012, the FTC sent warning letters to the providers of six mobile applications that can be used to obtain background screening information about individuals, allegedly including criminal history information.23 The letters raised concern that such information could be used to make decisions about an individual’s eligibility for employment, housing, or credit, in violation of the FCRA.

The companies that received the letters are Everify, Inc., marketer of the Police Records app, InfoPay, Inc., marketer of the Criminal Pages app, and Intelligator, Inc., marketer of Background Checks, Criminal Records Search, Investigate and Locate Anyone, and People Search and Investigator apps.

According to the letters, each company had at least one mobile app that involves background screening reports that include criminal histories, which are likely to be used by employers when screening job applicants. The letters explain that, in providing such histories to a consumer’s current or prospective employer, the companies are providing “consumer reports” and therefore are acting as a “consumer reporting agency” (CRA) under the FCRA. The FTC reminded the companies of their obligations – and their apps users’ obligations – to comply with the FCRA if they had reason to believe their reports were being used for employment or other FCRA purposes. According to the FTC, “[t]his is true even if you have a disclaimer on your website indicating that your reports should not be used for employment or other FCRA purposes,” noting that the FTC “would evaluate many factors to determine if you had a reason to believe that a product is used for employment or other FCRA purposes, such as advertising placement and customer lists.”24

Although the FTC made no determination that the companies were in fact violating the FCRA, it encouraged them to review their apps and their policies and procedures to ensure that they comply with the law, reminding them that a violation of the FCRA may result in legal action by the FTC, in which it is entitled to seek monetary penalties of up to $3,500 per violation.

If you use mobile applications, social media, or any other form of new media and technology to conduct background checks on your current or prospective employees, be aware that such activity will most likely be covered by the FCRA, especially if such information is being used for employment or other FCRA-restricted purposes.

Robins v. Spokeo, Inc.

The case of Robins v. Spokeo, Inc.25 further illustrates the broad scope of the FCRA and how it applies to online entities and scenarios. In this case, Thomas Robins (the plaintiff), on behalf of himself and others similarly situated (a bit of legalese required in class-action lawsuits to include all eligible plaintiffs), initiated a class-action lawsuit under the FCRA against a search engine operator for collecting and disseminating false (and unflattering) information about him.

The defendant’s website (Spokeo) enables users to connect with family, friends, and business contacts by searching for a name, email address, or phone number. Spokeo provides an in-depth report that displays the searched party’s name, phone number, marital status, age, occupation, names of siblings and parents, education, ethnicity, property value, and wealth level.

Further, according to Robins in the complaint initiating the lawsuit, Spokeo markets itself to “human resource professionals, law enforcement agencies, persons and entities performing background checks, and publishes individual consumer ‘economic health’ assessments,” previously referred to by the defendant as “credit estimates.”

The court initially dismissed the case because Robins failed to plead actual or imminent harm or injury, which is necessary to achieve standing—that is, a personal stake in the outcome of the controversy sufficient to entitle a party to bring the lawsuit.26 (For purposes of standing, the harm must be “actual” or “imminent”, as opposed to conjectural or hypothetical. Allegations of possible future injury are generally insufficient to confer standing.)

Robins (who was unemployed) subsequently filed an amended complaint, wherein he alleged that he suffered actual harm in the form of anxiety, stress, concern and/or worry about his diminished employment prospects due to the incorrect information posted about him by Spokeo, including his age, marital status, “economic health” and “wealth level.” The court found that the amended complaint contained sufficient allegations of harm for standing: “Plaintiff has alleged an injury in fact—the ‘marketing of inaccurate consumer reporting information about Plaintiff’—that is fairly traceable to Defendant’s conduct—alleged FCRA violations—and that is likely to be redressed by a favorable decision from this Court.”27

Surprisingly, after Spokeo sought approval to appeal the district court’s finding that Robins had standing, the district court reinstated its initial order (finding that the plaintiff lacked standing) and dismissed the case. The court held that:

It is important to note that the case was not dismissed on the alternative basis advanced by Spokeo denying that it was a consumer reporting agency under the FCRA. In dismissing the case on standing grounds, the court left open the issue as to what types of online content aggregators fall within FCRA’s purview. Prudence dictates, however, that whenever a company assembles and analyzes consumer credit information (including a consumer’s character, general reputation, personal characteristics, or mode of living—for example, wealth, credit, lifestyle, home, education, and political persuasion) and markets it to third parties for a fee via the Internet, the company should heed the provisions of FCRA.

Employers who do not fully comply with the FCRA face significant legal consequences.

Employers who do not fully comply with the FCRA face significant legal consequences—for example, if they fail to get an applicant’s authorization before getting a copy of their credit or other background report, fail to provide the appropriate disclosures in a timely manner, or fail to provide adverse action notices to unsuccessful job applicants. In addition to civil remedies for those injured by an employer’s noncompliance with FCRA—which includes recovery of either actual damages or up to $1,000 plus punitive damages for willful noncompliance,29 an employer who knowingly or willfully procures a consumer report under false pretenses may also be criminally fined and incarcerated for up to 2 years.30

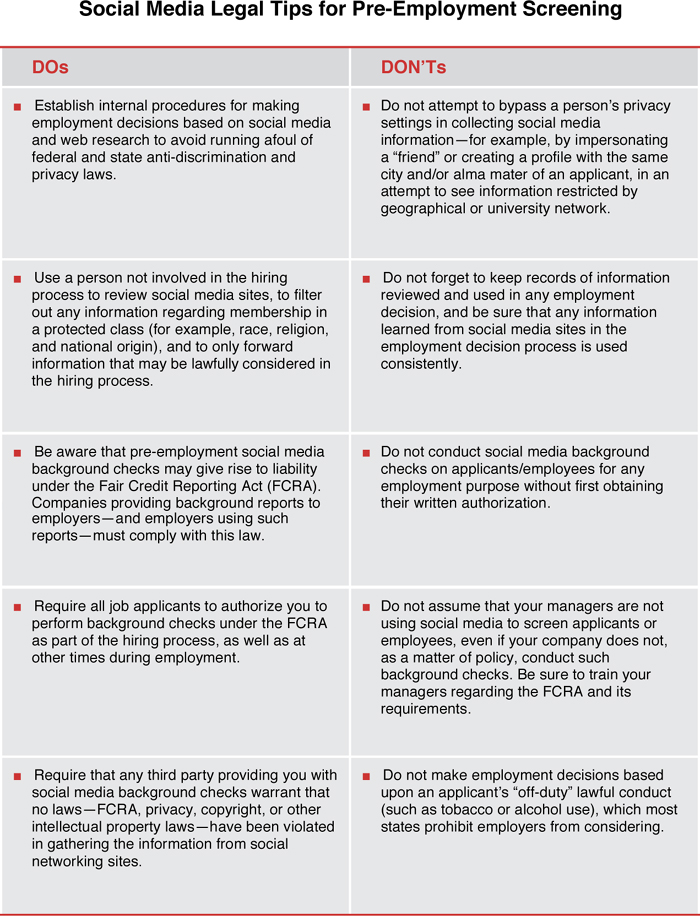

Bottom line: Like traditional consumer reports, when social media consumer reports are used in connection with making employment-related decisions, employers must ensure that the reporting and decision-making were performed in compliance with the FCRA. People involved in the screening and hiring process would be wise to adhere to the best practices summarized in Figure 3.3 in order to stay on the right side of the law.

Figure 3.3 Social Media Legal Tips for Pre-Employment Screening.

Chapter 3 Endnotes

1 http://recruiting.jobvite.com/resources/social-recruiting-survey.php

2 http://www.careerbuilder.com/share/aboutus/pressreleasesdetail.aspx?id=pr519&sd=8%2F19%2F2009&ed=12%2F31%2F2009

3 Minn. Stat. Ann. § 181.938

4 N.Y. Lab. Code § 201-d.

5 15 U.S.C. § 1681 et seq.

6 15 U.S.C. § 1681a(h)

7 15 U.S.C. §1681(b)

8 15 U.S.C. § 1681a(d)(1)

9 15 U.S.C. § 1681a(e)

10 15 U.S.C. § 1681a(f)

11 15 U.S.C. §§ 1681a(f) and 1681b(b)

12 15 U.S.C. § 1681b(b)

13 15 U.S.C. § 1681d

14 Id.

15 See 40 Years of Experience with the Fair Credit Reporting Act: An FTC Staff Report with Summary of Interpretations (July 2011), available at http://www.ftc.gov/os/2011/07/110720fcrareport.pdf

16 15 U.S.C. § 1681b(b)

17 15 U.S.C. § 1681m(a)

18 Id.

19 See FTC’s 5/9/11 Letter to Renee Jackson, Esq., counsel for Social Intelligence Corporation, available at http://ftc.gov/os/closings/110509socialintelligenceletter.pdf

20 Id.

21 Id.

22 See http://blumenthal.senate.gov/newsroom/press/release/blumenthal-franken-call-on-social-intelligence-corp-to-clarify-privacy-practice

23 See FTC Press Release (2/7/12), FTC Warns Marketers That Mobile Apps May Violate Fair Credit Reporting Act, available at http://www.ftc.gov/opa/2012/02/mobileapps.shtm

24 See, for example, FTC Warning Letter to Everify, Inc. (1/25/12), available at http://www.ftc.gov/os/2012/02/120207everifyletter.pdf

25 Robins v. Spokeo, Inc., Case 2:10-CV-5306 ODW (AGR) (C.D. Cal. Jul. 20, 2010)

26 Robins v. Spokeo, Inc., Case 2:10-CV-5306 ODW (AGR), slip op. at 2-3 (C.D. Cal. Jan. 27, 2011) (Order Granting Defendant’s Motion to Dismiss)

27 Robins v. Spokeo, Inc., Case 2:10-CV-5306 ODW (AGR), slip op. at 3 (C.D. Cal. May 11, 2011) (Order Granting in Part and Denying in Party Defendant’s Motion to Dismiss Plaintiff’s First Amended Complaint)

28 Robins v. Spokeo, Inc., Case 2:10-CV-5306 ODW (AGR) (C.D. Cal. Sept. 19, 2011) (Order Correcting Prior Ruling and Finding Moot Motion for Certification)

29 15 U.S.C. § 1681n-o

30 15 U.S.C. § 1681q

![3. The [Mis]Use of Social Media in Pre-Employment Screening](https://imgdetail.ebookreading.net/cover/cover/business/EB9780133033656.jpg)