The NetBeans IDE offers a highly customizeable environment through wizards and options that can be serialized. In this chapter you will learn how to customize your IDE environment. We will look at the following areas of customization:

Setup Wizard

Toolbars

Menus

Editors

Modules

The Setup Wizards allows you to quickly configure your IDE with some general settings required for everyday use. It is especially useful after an initial install of the IDE and is usually launched the first time you run NetBeans. To use the Setup Wizard any time after the initial launch select ToolsSetup Wizard from the menu bar.

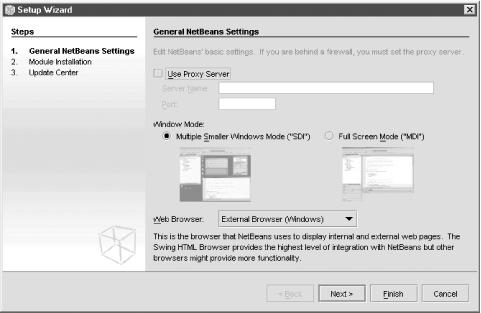

The first pane of the Setup Wizard, shown in Figure 6-1, allows you to configure a proxy server, a window mode, and an HTML browser.

The proxy server settings will be used for all the network and Internet needs of the IDE such as acquiring information for AutoUpdate from a remote Update Center. Your network administrator should be able to supply you with the server and port information of your proxy server. You will generally only need these settings if you are using the IDE behind a firewall.

The window mode setting is used to determine the type of windowing interface NetBeans should use. There are generally two types of interfaces: SDI and MDI. The main difference between the two interfaces is that in SDI mode, the IDE has no main window, and each workspace has its own window, whereas in MDI mode, all the windows are managed by a single window known as the main frame. Your choice of a window mode depends on your taste. They both have their advantages. In SDI mode the proliferation of windows for every document and workspace can be quite messy and annoying. The one benefit is that screen size per window can be maximized. In MDI mode there is one window and everything else is a child of that window. This makes window management very easy and agreeable for the programmer who already has 12 other applications opened. The one caveat is that because MDI child windows share space with a parent window, they cannot be maximized to take advantage of the entire screen area. This can be especially annoying with an editor window displaying Java source. It’s often convenient to minimize scrolling by showing as much text as possible. Microsoft Windows users may favor MDI mode because many Windows applications are MDI, including the DevStudio IDE.

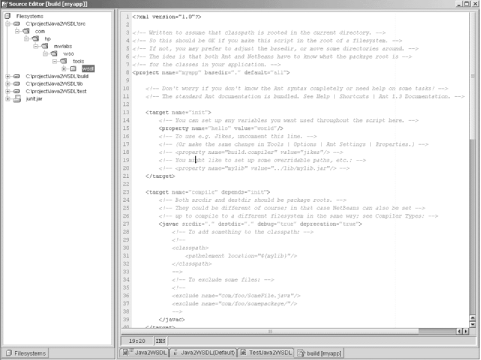

The differences between the two modes do not necessarily form a fork in the road, and neither of them can be considered “the road less traveled.” This is because the IDE lets you have the best of both worlds. In NetBeans, windows can be docked into one another. Windows—also referred to as frames—can also be made into separate windows, regardless of the mode you chose. This is an advanced level of customization for the NetBeans IDE, but it remains simple to accomplish. For example, if you chose MDI mode from the Setup Wizard, but would like your editor to be displayed as a separate window so that you could take advantage of more screen real estate, simply open a Java file; once the editor is opened select Window → Frame Resides → As Separate Window from the menu bar. You should now see the editor in a separate window. Conversely, if you preferred to dock the editor window and back Window → Frame Resides → As Separate Window into the main frame, you would select Window → Frame Resides → In IDE Desktop. You can also chose to combine multiple windows via docking. For example, to add the filesystem explorer to the left side of an editor window, set the focus to the filesystem explorer, select Window → Dock View Into → Source Editor → Left. Figure 6-2 shows an editor window with a filesystem explorer docked on the left.

The Web Browser selection is used for all the IDE’s browsing needs such as javadoc searching and JavaServer Pages (JSP) previewing. NetBeans comes with the ICE Browser embedded. This will usually be sufficient for all your needs and provides the tightest integration with the IDE; however, it lacks the feature-rich capabilities of some commercial browsers, and in that case you may wish to select an external browser for default HTML browsing. If you choose an external browser, you will have to configure it later by selecting Tools → Options and then expand the Web Browser’s node.

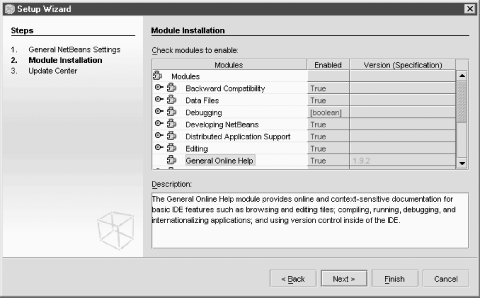

The second pane of the Setup Wizard (see Figure 6-3) allows you to configure which modules will be used by the IDE at runtime. The modules are shown in a table along with their enabled status (truefalse), version number, and description. Upon start-up, the IDE will attempt to load each of the enabled modules. This process becomes slower with the number and complexity of the installed modules. Memory usage is also a consideration because all modules are issued their own classloader and run simultaneously in memory. For these reasons it may not be desirable to enable every possible module. To disable a module, simply select false under the enabled column of that module’s entry.

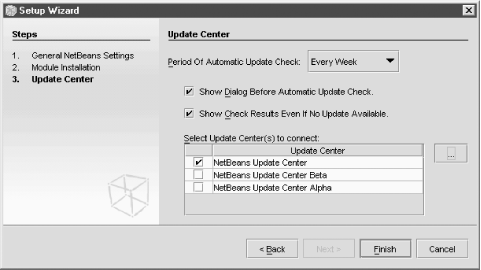

The third pane of the Setup Wizard, shown in Figure 6-4, allows you to configure the Update Center connection for the IDE’s Auto Update tool. The Auto Update tool connects to an Update Center to acquire modules and core components for installation. You can configure Auto Update to be automatically invoked on a recurring schedule, or you can manually invoke it any time by selecting Tools → Update Center... from the menu bar.

Most NetBeans global or project-level settings can be managed in the dialog invoked when you pull down Tools → Options dialog. The components in this dialog represent the vast array of configurable settings in the IDE. The components are organized in the left pane of this dialog in a tree of nodes. Each node represents a specific configuration component, and the folders represent categories by which the components are grouped.

When you select a component, its properties will appear in the left pane in a table that is known as the property sheet. Property sheets consist of two cells, a property name cell and a property value cell. Typically the property value cell is to the right of the property name cell. You can change a component’s settings by changing the data in its property value cell.

Some property value cells allow you to enter plain text. Others, such as true/false properties, will have a combo box of valid entries. Some value cells may require data that is not easily entered as text and will prompt you to use a special property editor. When the option to use a property editor is available, an ellipsis (...) will appear in the rightmost end of the cell when you click on it. Clicking on this ellipsis will launch the property editor for that cell. Cells that require Color values frequently provide property editors that allow you to choose colors from a palette.

You may want to change some settings globally. You may want to apply only other settings changes to the project you have open. Fortunately, NetBeans provides a means to specify the scope of a Tools → Options setting.

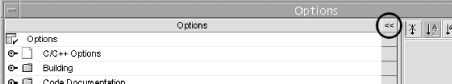

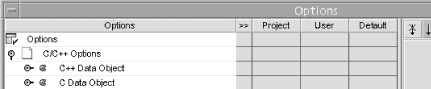

In Figure 6-5, we have circled a very small and important button. This button, which bears two left angle brackets, or “arrows” (<<) as its emblem, is called the Show Levels button. If you click it, a new panel “unfolds” into the options listing, and you are offered three choices for the level of settings persistence that can be applied on a per-setting basis, as shown in Figure 6-6.

The three choices for settings persistence are as follows:

- Default

Keeps the default settings shipped with NetBeans; doesn’t allow the user to apply any changes. Of course, if you change your mind, you can always remove this persistence to change the given setting. It’s just a safety net.

- Project

Settings changes are applied to the current project only. Any other project will retain the settings it was left with until they are changed while that project is open.

- User

All changes apply to all projects for that user.

You can click the Show Levels button again to fold back this settings persistence panel so that it’s out of your way.

Toolbars are similar to menus. They are panels consisting of image buttons that are mapped to a specific task. Each button on a toolbar will usually have a brief text description, commonly called a tooltip , and there may also be a sequence of keys associated with a button known as its shortcut key. The IDE comes preconfigured with several toolbars that would most likely be sufficient for everyday development tasks. If the preconfigured toolbars do not meet your needs, you can always modify them or create entirely new ones to perform your custom tasks.

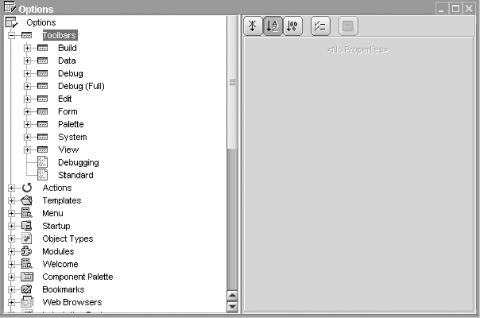

In the NetBeans IDE, each toolbar button is tied to an action. You may think of an action as a task. For example Cut, Paste, and Copy are all actions. Most of the IDE’s actions are prepackaged; others are provided by third-party modules. To begin configuring toolbars select Tools → Options and then go to IDE Configuration → Look and Feel → Toolbars. Figure 6-7 shows the toolbar options.

These options allow you to edit and delete existing toolbars or create your own. You can add new buttons to an existing toolbar by copying and pasting actions. For example, to add a new button to the Build toolbar for compiling, you would perform the following steps:

Expand the Build toolbar node.

Expand Actions → Build, right-click on the Compile node, and select Copy from the context menu.

Right-click on the Build toolbar node and select Paste → Copy from the context menu.

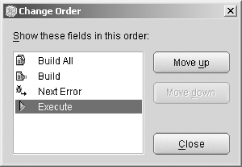

You can also rearrange the ordering of toolbar buttons. To change the button order on a particular toolbar, right-click on its node and select Change Order from the context menu. You will be presented with the dialog box shown in Figure 6-8. Use the Move Up and Move Down buttons to reorder each toolbar button’s position. The toolbar button at the top of the list will appear first from the left on the toolbar.

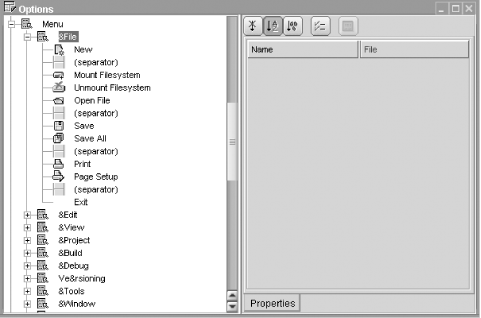

The IDE also allows you to edit and create menus in the same way you edit and create toolbars. To begin editing and creating menus open the options dialog box (Tools → Options) and go to IDE Configuration → Look and Feel → Menu Bar. You should see a list of nodes similar to the ones shown in Figure 6-9 that represent your current menu bar. By expanding each menu, you will see a list of menu items. An item can be either an action or a separator. Menus can also contain submenus.

To add a submenu to a menu, right-click on the menu node and select New → Menu from the context menu. The new menu is immediately viewable under the menu where you created it. Adding a menu item requires steps similar to the aforementioned toolbar button steps. After copying an action, right-click on the destination menu node and select Paste → Copy from the context menu. The reordering of menu items within menus is done exactly the same way toolbar buttons are reordered (right-click a menu node and select Change Order... from the context menu). You can also delete and rename menu items and menus in much the same way you would any node in the IDE. There is also an easy way for mapping shortcuts to menus. When supplying a name for the menu, type an ampersand (&) in front of the letter you want to map. For example, “&File” will be mapped to the shortcut Alt-F.

Of all the components in the IDE, the editor will most likely be the one involved in your day-to-day programming use. Therefore it makes sense that it is one of the most configurable of all the components in the IDE. Although it may seem that you are always working with one editor, there are in fact different editors for different types of files. A file type is identified by its extension. The mapping of editor to file type is a one-to-many relationship. Although the content they handle may be different, editors share a common set of configurable attributes. Some editors may choose to disable some of these attributes because of the irrelevance to the particular implementation—for example, the Auto Popup Code Completion feature is disabled in the Plain editor. Editors for some object types may have multiple views; in such cases special menu items are provided for switching between views. For example, there is a specialized editor for modifying Properties files. That editor has two views: one provides a table for editing properties and values, and the other provides a plain text view. Selecting Open from the context menu for a Properties file results in the default view, which is the table view. To access the alternate plain text view, select Edit from the context menu.

As previously mentioned, editors are mapped to file and MIME types. In the IDE, a file is basically a type of object. The IDE uses Object Types to identify files based on their extensions. Object Types do not always map to files. Some are used internally as objects by modules. You can map several file extensions to a single Object Type, thereby associating the files with those extensions to a particular file type in the IDE. For example, adding java as an extension to the Java Source Object Type would make all files ending in .java recognized as Java file types in the IDE. The real power of Object Types comes in when you associate actions with an Object Type. Actions are objects in the IDE that are mapped to menu items and used to carry out a specific task on a target object. Compile is one example of an IDE action. The Compile action can be used on Java Object types to invoke a configured Compiler Service with a Java file as its target. Nothing stops you from adding the Compile action to an Image Object Type. If for example you had a special Compiler Service that converted GIF to JPEG, it would be useful to be able to right-click on a .gif file, select Compile from the menu, and have your file converted. Configuring Object Types makes all this possible. Usually Object Types come with preconfigured actions and extensions. You would only need to change these to add custom behavior.

Table 6-1 shows some common Object Types and their descriptions.

Table 6-1. Object Types

|

Object Type |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Form |

Objects that refer to Java source files that have IDE-managed GUI code in them |

|

NBM |

Objects that refer to NetBeans Modules files that can be used to install modules |

|

HTML |

Objects that refer to HTML files |

|

JSP |

Objects that refer to JSP files |

|

XML |

Objects that refer to XML files |

|

Java Source |

Objects that refer to Java source files |

|

Properties |

Objects that refer to Properties files, which usually contain name/value pairs |

|

Image |

Objects that refer to IDE-supported images (ex. gif, jpeg) |

|

Class |

Objects that refer to compiled Java classes |

|

Text |

Objects that refer to arbitrary text files |

Usually the only property of an Object Type you would configure would be the extensions. This is useful if you would like to add a new extension so that it is recognized by the IDE. For example, if you want the IDE to recognize files with the jad extensions as Java Source files, simply go to the Java Source Objects node and in the property sheet click on the pane to edit the Extensions and Mime Types. Click on the ellipsis that appears and you should see a dialog box like the one shown in Figure 6-10. Enter “jad” (you enter extensions without the dot prefix) in the input box and then click add. Close the dialog box. Any files in your mounted filesystems that have a jad extension should now appear with the icon denoted for Java source files. When you double-click the file, you should see the source code in the Java editor.

At the heart of Editor configuration is the Editor Settings. The Editor Settings node can be found in the Options Dialog under Editing → Editor Settings. When you expand this node, you will see all the various editors in the IDE. Usually an editor’s name will give you a good idea of the types of files it supports. Most of the editors have the same configuration parameters; however, you will be able to configure them separately and maintain your changes.

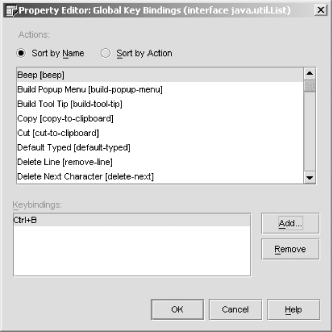

Key bindings are the mapping of keys to predefined IDE actions. For example, the mapping of the Control key and the C key combination is to the Copy action. Many combinations can be mapped to a single action. Each mapping is known as a binding because the sequence of key strokes is bound to the particular action. Global Key Bindings are inherited by all the editors. Each editor also has its own specific bindings that can override global key bindings or provide their own mapping. Global key bindings are configured by selecting the Editor Settings node, clicking on the Key Bindings cell in the property sheet, and then clicking on the ellipsis (...) that appears. You should see a dialog box similar to the one shown in Figure 6-10. The predefined actions are shown in the List box and can be sorted by name or action (the internal action name). To add a new binding, first select an action from the list and then click on the Add... button. In the dialog box that appears, enter the key sequence that will cause the IDE to invoke the action. For meta keys such as Control and Alt, you will need to hold on the key while typing. So for binding the beep action to the Control key and B key combination, you would hold on the Control key while typing B in this dialog box. After clicking OK to close the dialog box, the new key binding should appear in the Keybindings list box.

You can modify an editor’s local key bindings by selecting that editor from the list of nodes under Editor Settings and editing its Key Binding property. This behaves exactly like the global options except that these local options override any existing global key bindings for the specific editor with which the binding is associated.

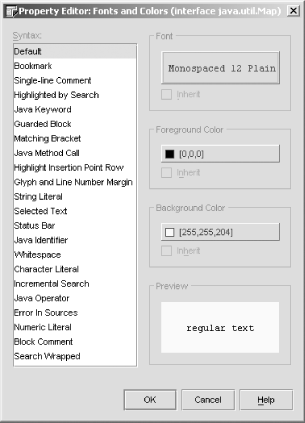

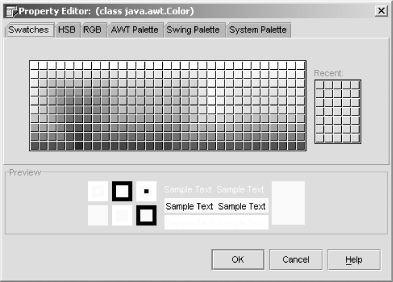

Each editor has its own properties for fonts and colors. Color is divided into foreground and background and is individually configured for each syntax element of an editor. For example in the Java Editor, Java Keyword is a syntax element and it has its own foreground and background color properties. So for a keyword such as if the foreground and background color properties selected would be shown whenever it is typed. There is a default syntax element whose properties the other syntax elements can inherit or override. This allows you to set a consistent background color, for instance, and only chose different foreground colors for various elements. Fonts are also chosen independently for each syntax element and may be inherited from the default. To modify fonts or colors for a particular editor, select that editor from the nodes under Editor Settings, click the Colors and Fonts cell in the property sheet, and then click on the ellipsis that appears. You should see a dialog box that looks like Figure 6-11. Syntax elements are listed in the list box to the right. Click on an element to modify its font and color properties. The Default element should be at the top of the list. To change the background from the white default to a light yellow (the color of a sticky pad for instance), select the default syntax element, click on the button in the Background Color box, and then click on the ellipsis that appears. You should see a dialog box like the one shown in Figure 6-12. This is the color picker dialog box. Each tab shows a pallete from which you can chose colors. Use the first pallette to select the light shade of yellow. As an alternative, instead of clicking on the ellipsis and using the color picker, you could type in the RGB color code in the edit box. The RGB color code for this shade of yellow is 255,255,204.

Your default background color should now be set; however, some of the syntax elements may not choose to inherit this property. You will need to go through the elements and click the Inherit check box in the Background Color. This causes the background color chosen for the default syntax element to be applied to the current syntax element.

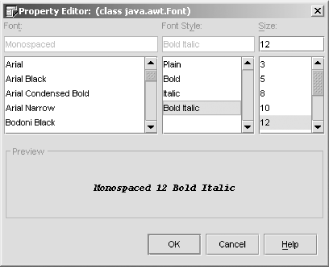

Choosing a font is just as easy as choosing colors. To modify the font for single-line comments in the Java Editor, changing it from plain italics to bold italics, click on the button in the Font box and then click on the ellipsis that appears. You should see a dialog box similar to the one shown in Figure 6-13. In the first list you select the Font name. The second list allows you to configure the syle of the font. For this example you would select Bold Italic from that list. The third list allows you to select the font size. Once you have configured the font settings, click OK to close the dialog box. The settings in this example should only affect single-line comments (comments that begin with //). Now every time you type a single-line comment, it will appear as a font with a bold-italic style.

In Chapter 2 you learned about macros in templates that were used for string expansion. In this section you will learn about a different macro used to execute a task on a particular editor. You can refer to these as editor macros. Editor macros can be recorded, saved, and executed. An editor macro can only be executed in the editor in which it was recorded and saved. Finally an editor macro is mapped to a shortcut key so that it can be easily invoked through convenient keystrokes.

Let’s say you were using a logging class that would emit messages to a log file when the log method was called with the classname and log message as parameters. The static method signature is:

Logger.logMessage(this.getClass( ),"message");

Instead of having to type that every time you want to log a message, an editor macro can be created to type the entire method signature and then position the caret between the quotation marks so that a message can be typed.

To begin recording your macro, open a Java source file. This macro will be available for all source files opened with the Java editor. Start the macro recorder by typing Control-J and then S (hold Control key, type J, release Control key, type S). You should see the message “Recording” appear in the editor’s status bar (the message goes away once you begin typing). Every keystroke beyond this point is recorded as part of the macro. Type the following code snippet:

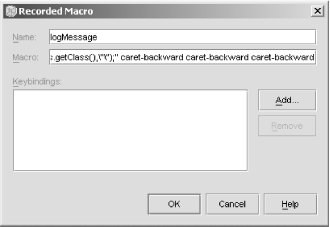

Logger.logMessage(this.getClass( ),"");

When finished typing, use the back arrow key to move the caret between the two quotation marks. Type Control-J and then E to end the macro recorder. A dialog box like the one shown in Figure 6-14 should appear. Type in a canonical name for the macro in the Name edit box and then click the Add... button. Another dialog should pop up, prompting you to enter a key binding for this macro. Type in a key sequence that you find convenient, for example Alt-Shift-0 (do not type in the plus sign or hyphen and remember to keep holding meta keys such as Alt while you type). Click OK and your new macro should be saved.

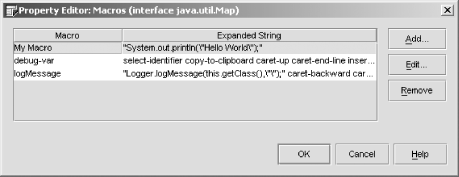

After a macro is saved, it becomes one of the properties of the editor in which it was recorded. The macro we wrote in the previous section will be available to any source file opened with the Java editor. To modify the macro we can edit it through the macro property found in the property sheet for the particular editor. Click on the Macros cell to edit the property and click on the ellipsis. You should see a dialog box similar to that shown in Figure 6-15. Select the macro you want to edit from the table and click on the Edit... button to change the name or macro expansion.

To execute the macro, type the keyboard shortcut anywhere in the editor. For this example we used Control-Alt-0, so typing that will execute the macro and we should see the code with our caret positioned between the quotation marks.

The IDE uses the concept of an indentation engine to format code in the Source Editor. Setting the width of tab spaces, adding a leading asterisk to comment lines, and placing spaces before parentheses are some examples of its use. You can create two types of engines, a Java Indentation Engine or a Simple Indentation Engine. The Java Indentation Engine has more options and is specific to formatting Java source code. Simple Indentation only allows you to configure the number of spaces for tab. Table 6-2 shows the properties of the Java Indentation Engine.

Table 6-2. Java Indentation Engine properties

|

Property |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Add Leading Star In Comment |

If this property is set to true, the IDE will automatically add an asterisk (*) to the beginning of every line in a multiline comment (a comment starting with /* or /**). |

|

Add Newline Before Brace |

If this property is set to true, the IDE will start the brace for functions, classes, and other scopes, on the next line. |

|

Add Space Before Parenthesis |

If this property is set to true, the IDE will add a single space before each opening parenthesis. |

|

Expands Tab To Spaces |

If this property is set to true, the IDE will add spaces (equal to the number of spaces per tab property) each time the tab key is pressed. Otherwise the IDE will advance the caret to the position necessary for the tab and insert the tab character ( ) into the file. |

|

Number of Spaces Per Tab |

This property sets the number of spaces that the caret should advance when the tab key is pressed. |

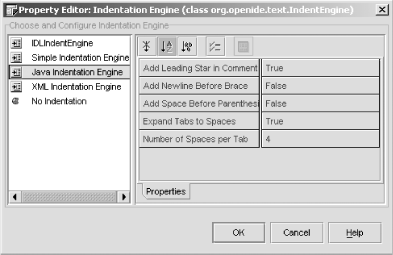

You can associate an engine with any of the editors by selecting the editor from the list of nodes under Editor Settings, clicking on the Indentation Engine cell in the property editor, and then clicking on the ellipsis. You should see a dialog similar to the one shown in Figure 6-16, allowing you to select an Indentation Engine and configure it. Many editors can use the same engine. Changing the engine’s settings will affect all the editors that reference it.

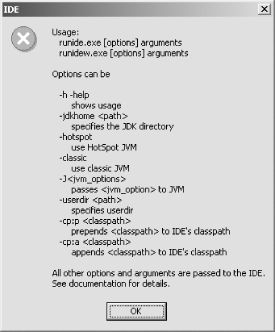

The IDE can be run from the command line with arguments. At the command line type runide.exe -help (runide.sh on UNIX systems) and you will see a dialog box like the one shown in Figure 6-17 with the command line options.

These options are shown and described in Table 6-3.

Table 6-3. IDE command line arguments

|

Argument |

Description |

|---|---|

|

-h or -help |

This argument displays the help dialog. |

|

-jdkhome |

This argument sets the directory where the IDE is to find the installed JDK. |

|

-hotspot |

If this argument is supplied, the IDE will use the hotspot JVM as opposed to classic. |

|

-classic |

If this argument is supplied, the IDE will use the classic JVM as opposed to hotspot. |

|

-J<jvm_options> |

This argument allows jvm options to be passed to the underlying JVM (i.e., the parameter is not used by the IDE). For example, setting the JVM stack size to 96 MB can be specified with -J-Xss96m. |

|

-userdir |

This argument specifies the user directory that the IDE will use to store project settings and user-specific information. |

|

-cp:p <classpath> |

This argument prepends the specified <classpath> to the IDE’s classpath. |

|

-cp:a <classpath> |

This argument appends the specified <classpath> to the IDE’s classpath. |

Instead of typing the arguments at the command line each time you run the IDE, you can save your settings to a file that is read into the IDE as command line parameters. Your arguments need to be in the ide.cfg file found in the bin directory of your installation. For example, if you wanted to specify xerces.jar ahead of the IDE’s classpath and set the maximum heap size to 256MB, your ide.cfg file will consist of a single line that looks like this:

-cp:pc:xerceslibxerces.jar -J-Xmx256m

Modules are what make the NetBeans IDE extensible. The IDE consists of a thin layer known as the core on top of which are modules that provide most of the features you use. In the second part of this book you will learn how to create modules and build the IDE sources with minimal modules. This section gives you an introduction to modules and shows you how to install, uninstall and configure them in the IDE.

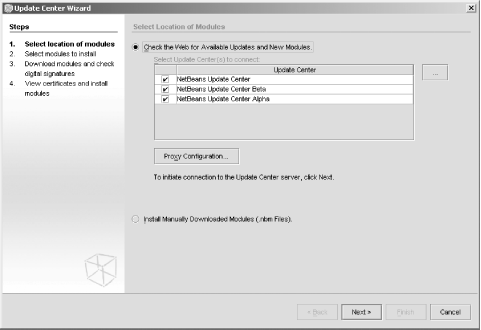

The IDE allows you to install modules from NetBeans Update Centers (available through the web) or manually downloaded NBM files. Both of these methods are accomplished using the Auto Update Tool. To use Auto Update select Tools → UpdateCenter. You will see a dialog box like the one shown in Figure 6-18.

If you are installing modules from the web, select the Update Centers you want to connect to from the list provided and click next. If you are behind a firewall, you will need to click on the Proxy Configuration button and supply the proxy server and port.

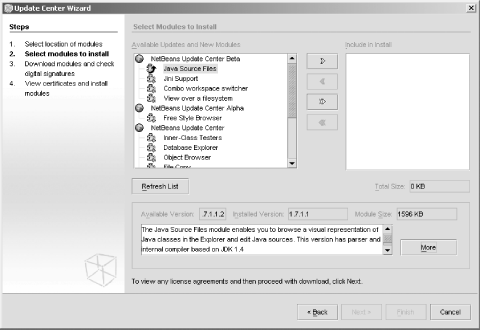

If you chose to install from the web and clicked the next button, you should see the next pane of the wizard as shown in Figure 6-19. If you do not see this pane, there may be something wrong with your Internet connection, or the Update Centers you chose were invalid or experiencing network problems. Another cause for problems could be your proxy settings. Check your settings, or consult with a systems administrator if you’re using your company network, and try to connect again.

The modules are listed under each Update Center you selected in the first pane. When you select a module, the dialog displays the module’s version information compared to what you currently have installed. The text box gives a description of the module and what it does. A web page giving more information about the module can be viewed by clicking on the More button. To select a module to be installed, select the module’s node in the left list box and then click on the arrow pointing to the right or to the Include To Install list box. You can select multiple modules by holding the Control key while selecting and use the same arrow to chose those modules for installation. The other arrow button pointing to the right allows you to select all the modules for installation. Click the next button and you might see a license agreement. If you chose many modules, you might have to click Accept on each of the license agreement dialogs that pop up. After accepting the license agreement, the IDE will attempt to download the modules and check for any digital signatures. When the downloading is complete, click Next for the last pane.

This is the final pane. You should see a list of modules that were downloaded. If the module is digitally signed and has a valid certificate, it will appear with the word “Trusted” under it. You can select a module and click the View Certificate button to view its digital signature certificate. The checkbox to the left of a module indicates whether you want this module installed when you click the Finish button. Checking it means you would like it installed. The IDE must be restarted for a module to be utilized. You can choose to have the IDE restart immediately (don’t worry, your files will be automatically saved first) or install immediately and restart later at your own convenience. Once you click the Finish button, the module will be installed.

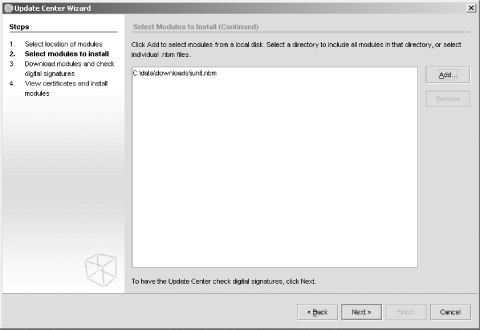

If you chose to install manually, you should see a dialog box like the one shown in Figure 6-20 after clicking Next on the first pane. This pane allows you to add .nbm files. You can use the Browse button to find .nbm files on your local system or on the network. Once you click the Next button, the wizard will be the same as the previously explained web module installation.

By default, when a module is installed, it is enabled. To improve performance and startup time you might want to run with a minimum set of modules. In this case you need to disable the modules you won’t be using. To disable a module, select Tools → Options under IDE Configurations → System → Modules and find the module category for your module. Usually third-party modules will create their own module category. You can chose to disable an entire module by selecting the category and chosing false for the enabled property in the property sheet. Under the category’s node are the specific module features. These can be disabled as well by chosing false in the enabled property of the feature. By disabling the category, all module features are instantly removed from the IDE until the category is enabled by chosing true for the enabled property.