From classical ballet to tango, in many different styles of dancing, the bodily aesthetic plays an important role. A slim, well-proportioned physique seems to be the embodiment of dance. This also has practical reasons, since lifts, acrobatic steps, and partnering all call for lightness in weight, as well as flexibility and good technique. Problems arise when physical attributes, such as slim and well-proportioned, start to be mistaken for being successful and happy. Such attitudes can be detected in modern society, and also in dance.

Our appearance – height, figure, weight – is determined by our genetic predispositions, our metabolism, as well as our eating habits, level of physical activity, and general lifestyle. While nutrition and amount of exercise can be adjusted, genes still play a major role, especially in determining height, proportions, and the muscularity. The statistics paint a gloomy picture: in Central Europe, about two thirds of men and women are unhappy with their figures, and in dance, the percentage is even higher. The high expectations of what the ‘ideal’ dancer should look like, frequent glances into the mirror, tight, form-hugging dancewear and an atmosphere of constant competition all contribute to an increased focus on the body and make it easy to forget that being thin does not automatically mean being a better dancer. For many dancers, it is a balancing act to maintain a slim figure, while also eating enough to have the necessary energy and strength for trainings, rehearsals, and performances.

How Many Calories Does a Dancer Need?

In order to estimate caloric needs, a dancer’s energy balance must be examined more closely. It depends on age, sex, body structure, lifestyle, and training.

The amount of energy a body needs to maintain its basic functioning when resting is called the resting or basal metabolic rate. Even when we lie flat without moving, the body needs energy, for example, to fuel the heart and circulatory system as well as the kidneys, intestines, and activities of the brain. This basal metabolic rate is measured in standardized conditions when one is lying in a relaxed position, 12 hours after having eaten and in an environment of 20°C. It depends on age, sex, and the bodily surface area, among other things. Intensive training, growth, or stress cause the basal metabolic rate to rise; long-term fasting and extremely reduced caloric intake, on the other hand, cause it to drop.

Table 6.1:Influencing factors for the basal metabolic rate (BMR)

| Age | The older one is, the lower the BMR | |

| Sex | Men have a higher BMR than women | |

| Height | The taller one is, the higher the BMR | |

| Weight | The heavier one is, the higher the BMR | A thin dancer has a low BMR. |

| Amount of muscles | The higher the percentage of muscles, the higher the BMR | A dancer with well-developed muscles has a higher BMR. |

| Calorie consumption | Long-term fasting with a caloric intake below that of the BMR lowers the BMR even further. | A dancer who regularly eats fewer calories than their BMR will reduce their BMR even further. |

My basal metabolic rate:

My basal metabolic rate:

Women:

655 + (9.5 × ______ weight in kg)

+ (1.8 × ______ height in cm)

– (4.7 × ______ age) = _________ kcal

Men:

66 + (13.7 × ______ weight in kg)

+ (5 × ______ height in cm)

– (6.8 × ______ age) = ________ kcal

According to Harris/Benedict, 1919; modified by McNeill, 1993.

Your Total Energy Needs – Movement Is the Key

The total metabolic rate is made up of the basal metabolic rate and the amount of daily physical activity. This is classified according to the so-called PAL-value (Physical Activity Level): the higher one’s daily physical activity, the higher the PAL-value. Multiplying your basal metabolic rate with the corresponding PAL-value gives your total metabolic rate, hence your daily requirement for calories.

Table 6.2:PAL-value

| Amount of training | PAL |

| No training | 1.4 |

| Easy training load (about 5 hrs/week) | 1.6 |

| Medium training load (about 10 hrs/week) | 1.8 |

| High training load (>15 hrs/week) | 2.0 |

My total metabolic rate:

My total metabolic rate:

______ basal metabolic rate × _____ PAL-value = _____ kcal

Table 6.3:Total metabolic rate in dance, two examples

| Female dancer, 55 kg, 167 cm, age 22 | Male dancer, 67 kg, 176 cm, age 21 |

| Basal metabolic rate:

655 + (9.5 × 55) + (1.8 × 167) – (4.7 × 22) = 1375 kcal |

Basal metabolic rate:

66 + (13.7 × 67) + (5 × 176) – (6.8 × 21) = 1721 kcal |

| Total metabolic rate with medium training load:

BMR × PAL 1.8 = 2475 kcal/day |

Total metabolic rate with medium training load:

BMR × PAL 1.8 = 3098 kcal/day |

| Total metabolic rate without training:

BMR × PAL 1.4 = 1925 kcal/day |

Total metabolic rate without training:

BMR × PAL 1.4 = 2409 kcal/day |

| Needs 550 kcal more per day when training | Needs 689 kcal more per day when training |

Many dancers are surprised when looking at the amount of calories used in training. In spite of their body’s intuition, the number is regarded as being pretty small. This is due to the type of exercise dance involves. Usually a dance class is characterized by short intensive exercises, intermittent, with breaks for corrections, or explanations of the choreography, or waiting times while other dancers have their turn. Thus, the ‘net time’ of training is often considerably lower than its ‘gross time,’ which becomes noticeable when looking at the energy expenditure.

The basal metabolic rate declines with age. Thus, the total metabolic rate also declines even if the level of physical activity remains the same.

An individual’s daily calorie needs are not only dependent on length and intensity of training but also on their level of fitness. Trained dancers need less energy for the same work than untrained dancers. Due to their better muscular co-ordination and dance technique, their bodies learn to economize their movements. Muscular dancers need a higher intake of calories because bigger muscles use more energy. This is why, in general, male dancers need more calories than female dancers, even when performing with similar levels of intensity.

Table 6.4:Energy expenditure (kcal) in dance per hour

| Training intensity | Kcal/h |

| Easy | 180 |

| Medium | 290 |

| High | 360 |

Modified according to Beck et al., 2015. Since the use of energy during dancing is dependent on many different factors, the general rates of calories burned can only be given as an approximation.

Every training session changes the body. Depending on what the training focuses on, it can build muscles, reduce body fat or make the fascial tissue more elastic. Yet, these changes have their limits. Genes play an important role when it comes to the body’s figure. Every person has their individual proportions and individual ideal weight, which can only be altered permanently with great difficulty – in spite of intensive training and optimal diet.

Without reference to a person’s height, their weight does not convey much information about their body. Therefore, the so-called body mass index (BMI) is used as a tool to evaluate the relationship between one’s weight and height.

My BMI

My BMI

__________ weight in kg

_________________ = ___________

(__________ height in m)²

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Example: female dancer, weight: 55 kg, height: 1.67 m

55 kg

_________________ = 19.7

(1.67)²

The BMI allows for an assessment of whether someone’s weight is normal, underweight, or overweight. Those who are overweight have a higher risk of so-called ‘diseases of civilization’, such as high blood pressure or diabetes, while people who are underweight face the risk of being malnourished. If malnutrition is combined with the serious physical strain of dancing, it can be very dangerous to your health (see p. 123).

Table 6.5:BMI assessment for adults

| Severely underweight | <17 |

| Underweight | 17–18.5 |

| Normal weight | 18.5–25 |

| Overweight | >25 |

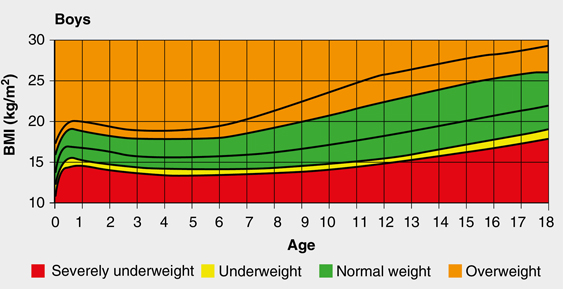

For children and adolescents under the age of 18, the BMI is scaled according to so-called growth curves. These curves differ for girls and boys. By comparing the BMI to the corresponding age, one can assess the child’s weight category.

Diagram 6.1a and 6.1b:BMI growth curves for children and adolescents up to the age of 18 with regard to age and sex.

Modified according to Kromeyer-Hauschild, 2001 and Kromeyer-Hauschild, 2015.

Body Fat – an Unpopular Necessity

From the outside, it is hard to determine what a body looks like on the inside. Even the BMI does not tell us what the relationship of muscles to fat, or of connective tissues to bodily fluids, may be. Thus, the bodies of two female dancers with the same BMI can look very different depending on their percentage of body fat.

Diagram 6.2:Two dancers of the same height and weight, but with different body fat percentages. Female dancer A: 55 kg, 1.67 m, 22% body fat; female dancer B: 55 kg, 1.67 m, 17% body fat.

Modified according to Mastin, 2009.

Determining the percentage of body fat gives us an insight into the body composition and an assessment of possible health risks. This is especially important in professional dance, where being slim often takes highest priority. A dancer’s health needs body fat (see Chapter 1, p. 20), and a sufficient amount of body fat is essential for optimizing performance. Fat performs two main functions in the body. As a structural component, fat takes on important protective functions in the body. The heel cushion, for example, serves as a padding and shock absorber for the foot; structural fat around the kidneys holds them in place and protects them from bangs and knocks. On the other hand, fat serves as a storage for energy. Adipose tissue or fat mass is found in the layers underneath the skin and in other selected parts of the body. Fat is stored in fat cells; having thin elastic walls, these cells can stretch to accommodate a larger amount of stored fat. These walls can stretch to accommodate larger amount of stored fat. The number and location of the fat cells in our body is genetically determined and there is little we can do about our individual paddings. What we can alter, however, is to what extent these cells are filled.

The relationship between muscle tissue and body fat is crucial for one’s metabolism and energy balance. Every muscle uses energy, meaning that a muscular build increases one’s need for energy. Fat tissue, however, is hardly relevant for the metabolism.

Age, sex, and level of fitness determine an individual’s normal percentage of body fat. In general, women have a higher percentage of body fat than men, and for good reason: fat is involved in the production and storage of the female hormone oestrogen. If the amount of body fat drops below a critical level, the level of oestrogen also drops, which can have grave consequences for a woman’s health (see p. 123).

Having a good level of physical fitness usually means having a lower percentage of body fat. Working out promotes the growth of muscles and causes fat reserves to recede. As one gets older an increase in body fat percentage is common, since muscle tissue is lost, even if one continues the same amount of physical activity.

Table 6.6:Body fat percentage related to the amount of training

| Training amount | Men | Women |

| Professional dancer | 5–10% | 12–15% |

| Amateur dancer | 11–14% | 16–23% |

| No dancing, little-to-moderate movement | 15–20% | 24–30% |

Modified according to Lohman/Going, 1993.

There are several methods for measuring a person’s body fat, yet their precision varies greatly. While determining one’s percentage of body fat is theoretically a helpful method for estimating the composition of the body, practical implementation can be difficult.

The most reliable measurements for body fat are those using the so-called volume – or radiation measurement method. Since they can only be carried out in certain laboratories, they are not practical for everyday use. One commonly used method is the skinfold measurement. A calliper is used to measure the thickness of subcutaneous fatty tissue in certain places of the body, then those figures are extrapolated to calculate the total body fat percentage.The reliability of these measurements is dependent on the experience of the examiner, and results, therefore, vary greatly from one examiner to the next. Another frequently used method involves body fat scales, which use measurements of electrical resistance in the body to determine its fat contents. This is possible because fat and muscle have different electrical resistances. However, these scales lack precision. Usually they only measure the body fat contents of the lower part of the body, as they only have pads for the feet. Only if the scales have additional hand sensors can the whole body be taken into account. Nonetheless, the results can still vary greatly, as wet feet, body lotion on the skin, hydration status, or a full bladder all have an effect on the measurements.

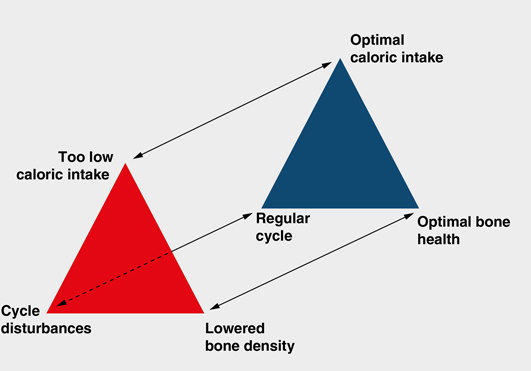

Maintaining Body Fat for Health

Low weight and a low percentage of body fat should raise red flags, especially if it occurs in female dancers. This constellation can lead to serious health problems often not noticeable until years later. The so-called Female Athlete Triad demonstrates the relationship between malnutrition and potential diseases. Reduced calorie consumption during high levels of physical activity is associated with irregularities in the menstrual cycle and reduced bone density. Restricting calorie intake over an extended period of time will lead to a shortage of important nutrients, vitamins, and minerals. A deficiency of calcium and vitamin D (see Table 1.10, p. 31) to stimulate bone formation, and of calories to maintain the body fat, will lead to serious health problems.

Diagram 6.3:The Female Athlete Triad – an overview of bone health

Modified according to Nattiv et al. (American College of Sports Nutrition Position Stand, 2007).

Fat is also important for the female hormone levels. If body fat sinks below a critical level, symptoms of oestrogen deficiency appear quickly. Menstruation becomes irregular or ceases completely. The statistics show that a concerning percentage of female professional dancers, between 30 and 55%, suffer from irregular menstrual cycles. Since many hormonal imbalances can only be detected via specialist medical examinations, we do not know the full extent of dancers’ hormonal imbalances, so the total number of female dancers being affected by hormone deficiency might even be higher. Although some women may think of their absent periods as ‘practical’, this absence of oestrogen causes health problems in the long run. Oestrogen regulates the rebuilding of bones. A deficiency weakens the walls of the bones, making them porous and fragile. Osteoporosis, which most people associate with elderly women, is a serious problem even for many young female dancers. The loss of density, and the changes in the bones’ microscopic architecture and mineralization, affects their stability and strength. The general bone quality deteriorates and, when this happens, even low levels of strain can break the bone, which is why stress fractures are not rare among female dancers.

The development of maximal bone density, the ‘peak bone mass’, is completed around age 25. After that, bone density slowly decreases. The higher your initial ‘peak bone mass’, the better prepared you are for ageing. Childhood and adolescence, in particular, are sensitive phases for preventing osteoporosis, as this is when the foundations for long-term bone stability are laid.

Tip

Vitamin D plays an important role in bones and muscles alike. If you frequently experience muscular injuries or weakness, see your doctor to have your vitamin D level tested. Vitamin D deficiencies are very common – also among dancers!

Table 6.7:Prevention of osteoporosis

| Ideal weight | If the body mass index of an adult woman is under 18.5, an especially balanced nutrition, rich in calcium, is recommended. |

| Oestrogen | Oestrogen is the key hormone for building bones. A late onset of menstruation as well as irregular or absent periods are signs of oestrogen deficiencies. Be sure to discuss this with your general practitioner/gynaecologist. |

| Calcium-rich nutrition | Calcium improves bone density and reduces the dismantling of the bones. Adequate calcium intake supports the bone density. |

| Vitamin D | Vitamin D is essential for calcium absorption into the bones. With the assistance of sunlight, the body can create its own vitamin D in the skin. Spending an average of 20 minutes a day outside can support the mineralization of the bones. Even short breaks should be used to stock up on sunlight. |

| Stop smoking! | Nicotine has negative effects on the metabolism of the bones and can promote osteoporosis. |

For some dancers, weighing seems to be a daily morning ritual, and even small variations in weight can cause intense mood swings. This is not a good way to start the day, as it is hard to enjoy your food and have a healthy attitude towards eating if your thoughts are constantly revolving around your weight. Few people realize that most bathrooms scales lack accuracy, and measurements can vary by several kilograms from scale to scale.

Tip

Do not be a slave to your scales!

Occasional weighing can make sense for self-monitoring – as long as you use the same scales. Yet, just as helpful is your own body perception, as one can feel changes in the body even without the control of scales.

Some people spend years trying to maintain their dream weight. When letting go of this dream and focusing on eating according to one’s needs, often the weight increases just a few kilos, but energy, fitness, and enjoyment of food will improve greatly.

Weight fluctuations of up to 2 kg are completely normal in female dancers. They can be caused through fluid retention during the menstrual cycle and will even out on their own.

Your weight is influenced by multiple factors. Stress or lack of sleep, for example, can strongly influence one’s weight. While they make some people lose weight, they seem to cause others to store every single calorie, and therefore to gain weight. Changes in your dance training – a new teacher, a more advanced level, or an unfamiliar dance technique – can have an effect as well. Often we misinterpret what is really a restructuring of our muscles as a change in weight, just from the way our body looks. Weight changes in puberty are especially dramatic, yet completely normal. If the bodies of young dancers start maturing, changes in proportions, figure and bodily composition will occur regularly. As it is all too easy to interpret these changes as ‘getting too fat’, particular attention and care is required to help guide young dancers through these natural changes. Keep calm and be patient. Often, the body will regulate and adapt to these changes on its own.

Dancing Influences One’s Weight

Regular dancing influences not only one’s figure and bodily composition, but also one’s weight. Yet, when the intensity of training increases, this does not automatically lead to a loss in body weight. On the contrary, increased training can result in muscle growth, which may cause your weight to go up. More training contributes to your muscles being provided with energy more quickly and in greater quantities. This also has an effect on weight: along with more glycogen, the carbohydrate reserves (see Chapter 1, p. 18), more water will be stored in your muscles; for every gram of glycogen, three times the amount of fluid is retained in the muscle. This can cause an increase in weight. Only when the bodily composition changes, after some time, and the percentage of muscular tissue increases due to the reduction of body fat, does this show on the scales. Yet this can take weeks, or even months, according to the individual metabolism and constitution.

Storing glycogen in the muscles causes fluid retention. If muscles are built up through training, this can lead to weight gain.

How Much Time Does It Take to Build Muscles?

Building muscles always requires both exercise and nutrition. It is only the combination of specific training with a nutritionally adequate diet that allows muscle growth. Since the metabolism of protein is rather slow, it can take weeks before you see any change. In order to build muscle, you have to consume more calories than you burn, ideally in the form of good quality, high-protein foods.

Is it Possible to Reduce the Size of Specific Muscles?

If the body is supplied with fewer calories than it needs for its total metabolic rate, it burns its reserves, causing a decrease in lean mass. This will affect the whole body and cannot be directed to muscles in a desired spot. Specific changes of muscle size can only be achieved through deliberate muscle training; by strengthening the ‘antagonists’ (opposing muscles) and the ‘synergists’ (supporting muscles) of a specific muscle group, the muscle work becomes more efficient – and the muscle smaller in size. Specific training of the hip flexors, along with the deep external rotators of the hips, for example, can counteract the excessive growth of the gluteus maximus (buttocks).

Is it Possible to Get Rid of Undesirable Fat Mass?

Dance training changes the composition of the body. Yet, when it comes to burning body fat, dancing is, in fact, not the most efficient workout. The way training is structured puts specific strain on the anaerobic system (see Chapter 1, p. 6), which does not usually affect fat reserves. Furthermore, the distribution of fat in the body is determined genetically. Which areas of fat will be increased or decreased is set in our genes and cannot be controlled by simply observing a healthy diet.

Everyone reacts differently to intensive training. Some people cannot eat a single bite after training, while others constantly crave chocolate. Some people even change their diet completely. Physical training can turn our nutritional habits upside-down, causing us to develop an appetite for different foods, combinations and portion sizes.

Increasing the amount of training increases the body’s energy needs. That can fuel one’s appetite. Cravings for sweets or fatty foods during the day or after training is usually the sign of an unbalanced diet. You are either not eating enough, causing your body’s energy to plummet and making your body crave a quick resolution, or the things you eat don’t provide you with the necessary nutrients. As a dancer, if instead of eating nutritious food, you try to satisfy your body’s high energy demands through sugar, fat, or ‘empty calories’, your body will soon ask for replenishment. This only increases the frequency of meals and the amounts eaten, but will not make the feeling of hunger disappear for substantial periods of time. Even bad timing of meals during the day can lead to hunger attacks. Make sure you time your meals right (see Chapter 4, p. 84). Ideally, begin the day with a healthy breakfast and have a sufficient supply of nutritious snacks on hand throughout the day. Make sure your main nutrients are well proportioned (see Chapter 3, p. 52). Some dancers need more carbohydrates, while others need more fat or protein to feel satisfied.

Tip

Dancing regularly can change your food preferences and your appetite. Pay attention to your body’s signals.

Some dancers are less inclined to eat something during short breaks or directly after class. The high level of physical activity has put the digestive tract on the back burner, and you feel neither hunger nor appetite. The longer and more intensive training is, the more likely you are to lose your appetite. Allow yourself time for the hunger to reappear, but be careful not to wait too long. After training, there is only a narrow window to resupply the glycogen energy stores in your muscles (see Chapter 1, p. 18). If it is not used, then the body loses its chance to regenerate and improve its performance capacity. If your appetite is low throughout the whole day, you run the risk of not supplying your body with enough calories. Pay attention to the times you do feel hunger and plan your meals accordingly.

A New Living Situation May Alter One’s Diet

A dancer’s life is marked by frequent changes. Already at the beginning of one’s professional career, it is often necessary to change cities or even countries in order to get a good education. Such changes are likely to intensify during your professional life. Job changes often involve starting in completely new surroundings. Most people know from going on vacation what a change of surroundings can do to your body; dietary habits get mixed up, one can experience feelings of fullness, problems with digestion or even changes in weight. New surroundings can stress the body and confuse the systems, and people experience these changes differently; some more, some less.

Tips

✓Give your metabolism time, it can take several months until it has adjusted to a new situation. Fluctuations in weight are not unusual in this period.

✓Find your own eating schedule in accordance with your training.

✓Bear in mind that you may now be working more intensively and may need more energy to keep up (see Chapter 6, p. 115).

✓Develop your own tastes; use cookbooks, the internet, recommendations from family and friends to find new recipes and to expand your repertoire.

✓When eating in a boarding school or cafeteria, pay attention to the quality and quantity. Changes in weight can depend upon ingredients and/or portion sizes (see Diagram 3.2, p. 74).

Getting Started – Dance Schools and Dance Education

Getting started at a professional dance school is a challenge in many ways, not least in terms of healthy eating. Different training times, schedules, and higher training intensities can put demands on the body and disrupt one’s habits. If this means also leaving your parents’ house then you must face the additional challenge of suddenly being in charge of your own diet. Either you are responsible for your own meals, or else must learn to deal with pre-set meal times in the boarding school cafeteria. Such stress factors can cause your weight to change.

In foreign countries, the food one is accustomed to may not be available or can only be found with difficulty. Unknown foods and new spices can cause havoc with the digestive tract and hence can also influence one’s weight. Language barriers and foreign surroundings can make it doubly difficult to find familiar foods.

Tips

✓Check around to see if and where you can find your familiar foods in the new environment.

✓Gradually begin to mix the things you know and love with local foods. Pay attention to the way your body reacts. Large amounts of unfamiliar foods can lead to irritations of the digestive system and even to food intolerance.

✓Take time to plan your grocery shopping and translate the names of the desired foods into the local language.

During longer training breaks, such as on vacations or in the summer interim, changes in weight are not unusual. During those times, your daily routine is altered, the lack of intensive training generally means you have more time to relax and be less stressed. If the break from training includes a home visit, comfort foods and favourite dishes are often part of the visit. This kind of security and feeling of getting to be spoiled for a bit is important, and is what makes family visits so comfortable. This can cause weight changes but should not be cause for concern.

Tips

✓Gaining a bit of weight on vacation is no reason to be alarmed. On the contrary, adding a few more calories can often help your regeneration.

✓Not training regularly or only attending less physically demanding workouts reduces your total metabolic rate (see p. 115). Over a longer period of time, this would require adjustments to your diet.

Injuries – Forced Interruptions in Training

During phases of injury it is necessary to maintain the balance between two very different demands: the sudden change in training intensity decreases the total metabolic rate. On the other hand, the body needs nutrients and building blocks and, above all, protein and antioxidants, to repair the injured tissues as quickly as possible. In this case, individualized nutritional counselling can be supportive.

Tips

✓As far as your injury allows, keep yourself fit and your metabolism active with an easy, adjusted training.

✓Make sure you eat enough protein! Several portions of protein every day support the reconstruction of your bodily tissues.

✓Antioxidants and high-quality unsaturated fats restrict the effects of waste products and aid regeneration (see Diagram 1.5, p. 29).

✓For injured bones, a high-calcium diet and time spent outdoors to build vitamin D aid in bone healing (see p. 123).

✓Make sure to drink enough liquids! This ensures a good circulation and a quick removal of waste products. This supports the healing process.

Most people associate ‘dieting’ with losing weight quickly and getting a lean figure in just a few weeks. Advertising promises tasty recipes and the chance to reduce one’s intake of calories without experiencing any hunger. Diets are popular, not only among dancers. Many women in Central Europe want to lose weight or are not happy with their figures; around half of all adolescents under 18 have already tried dieting. There are innumerable diets and often they give contradictory recommendations. From blood-type diets to leap-day diets, to detoxing; the long-term results of most of these dieting trends are disappointing and there is seldom an objective, scientific evaluation of them.

Many diets involve special products, specific food combinations, or prescribed recipes and strictly set meal times. They are complicated and need time. Not only must the shopping and preparation of the meals be integrated into the daily schedule according to the dietary regulations but also the ingestion itself. It is important to realize that precisely following a dieting plan takes your attention away from your own needs and leads you to ignore significant signals from your body. Instead of promoting individual changes to one’s diet, this method of dieting follows a ‘one-plan-fits-all rule’, and this rarely works out.

Strictly speaking, the word ‘diet’ does not refer to a practice of losing weight quickly, but covers a broad spectrum of various styles of nutritional intake. You might adopt a type of diet for health reasons, due to religious rules, based on medical recommendations, or out of your own choice. The variations of different diets are enormous. Whether vegetarian or vegan, gluten free, or low in histamines, all diets are based on a selective form of nutrition, which prescribes and limits the specific types of food to eat. If a dancer decides to take on any of these lifestyles, extra caution is needed. Dancing demands a broad repertoire of macro- and micronutrients. The body can only take the strain dancing puts on it when it is provided with sufficient amounts of these vital nutrients.

Dropping Weight Too Quickly – the Body’s Emergency Plan

‘Before opening night, you should lose a few more kilos.’ Comments like these from trainers, choreographers, or colleagues cause a lot of pressure. Often, they cause dancers to try to lose weight in extreme ways. To eat as little as possible or to skip meals completely seems quicker and easier than investigating your eating habits more broadly. Drinking very little water, excessive sauna programmes, or overdosing on laxatives all achieve just one thing: they put unnecessary strain on the heart and circulatory system, as well as on the digestive tract, and they put the body into a state of alarm.

The more rigorously calories are reduced and food intake is limited, the more drastic the effects are on the body. The result is that the body goes into energy-saving mode: metabolism and basal metabolic rate are reduced (see p. 114). At the same time, the body’s own reserves are mobilized. First, it turns to the glycogen reserves. This might be noticeable on the scales, but this quick reduction in weight is not due to the desired elimination of body fat. Together with glycogen, water reserves in the muscles are also released, and the body loses fluids. Once the glycogen reserves are empty, the body’s performance falters. The muscles get tired and heavy, and cognitive functions, like co-ordination, suffer. Now, the body starts using other energy reserves: fats and proteins. As burning fats for energy is slow in getting going when it comes to an emergency, the body begins to attack its own protein. The destruction of proteins causes the muscles to dwindle and worsens one’s physical ability even further. While one might have achieved the ‘perfect figure’ for opening night, it comes at huge costs to the body and severely affects one’s ability to perform.

Low-carb diets:

As a dancer, one should think twice about drastically reducing one’s intake of carbohydrates. Carbohydrates are the most important source of energy for the work of your muscles, and they help to reduce the body’s fat reserves. It is important to realize that carbohydrates do not make you gain weight, but too many calories, in whatever form, do!

Once the dieting stops, it is obvious what will happen next. Sliding back into old eating habits means one’s weight will soon be back to what it was before. The body has adjusted to the deficiency: if the intake of calories is reduced below the basal metabolic rate, the BMR will be decreased even further. Then, if you start eating again as before, the so-called yo-yo effect occurs: you might even put on more weight than you had before the diet.

Low-fat diets:

If the amount of fat in the diet is low, one quickly becomes hungry again. Thus, low-fat diets can lead to hunger attacks, during which one eats even more than normal. In addition, the lack of fat weakens the immune system, makes one prone to infections, and delays the healing of injuries (see Chapter 1, p. 20).

How to Lose Weight the Healthy Way

If you are unhappy with your weight, if your figure changes, or you gain weight inadvertently, no short-term turbo-diet will help. It is better to take a closer look and adjust a few crucial factors: everyday movement, dance training, additional stamina training and a balanced diet all play key roles in losing weight in a healthy way. Breaking old habits and bringing fresh ideas into one’s diet is not a simple matter. Eating patterns cannot be changed overnight. Be patient! Slowly, step by step, try different tastes, new products and adjusted meal times.

Eating fewer carbohydrates in the evening can help to reduce weight. Carbohydrates stimulate the insulin level in the blood, and insulin restricts the burning of fats. If the ingestion of carbohydrates is missing in the evenings, the body can burn fat through the night; but be careful: if you tend to be in a bad mood in the evening and you crave something sweet, then carbohydrate reduction might not be very sensible.

The right timing is an important key: don’t try to reconfigure your eating habits when experiencing stressful situations like an exam, an audition, or a performance, nor when you are experiencing phases of psychological stress or lack of sleep. Ideally, you should seek professional support: have a registered dietitian who understands dancers help you compile and analyze an eating protocol, which will be the basis to draw up a personal dieting plan. Self-observation is also needed: your energy levels, sleeping patterns, moods and, of course, your feelings of hunger and appetite are important indicators on your way to an individual, healthy diet.

Dieting, especially unhealthy dieting, can be a door opener to disordered eating.

Tips

✓Be careful you don’t eat too little. Eating too little will make your basal metabolic rate drop, which makes losing weight even more difficult. Healthy dieting means losing not more than 0.5 kg per week! This is about 500 calories a day or, at most, 20% of your daily total metabolic rate. Do not let your daily calorie intake fall below your basal metabolic rate.

✓Adjust the size of your meals to accommodate the main focus of your training sessions and alter the amounts of the macronutrients accordingly. But be careful: every macronutrient fulfils important tasks. Therefore, you should never eliminate carbohydrates, fat, or protein from your diet completely.

✓If possible, avoid ‘empty calories’ (see Chapter 3, p. 55). Numerous foods have been intensely processed. They supply you with calories, but hardly any vitamins, minerals or phytonutrients.

✓Replace snack foods with fruits and vegetables. These stimulate digestion and provide you with important antioxidants.

✓Eat sufficient amounts during the daytime and reduce your calorie intake in the evening. But watch out: if you lack the time to eat during the day, do not skip dinner.

Eating Disorders – Awareness Is the Key

If you lose pleasure in food, or if food or weight preoccupation becomes burdensome, it is time to pay attention – to yourself or to others. If your whole life and mental energy is spent contemplating food, this can be a sign of an eating disorder. Your daily schedule, your emotional state, and the decisions you make – all seem to depend on the question of eating or not eating. Happiness or unhappiness becomes dependent on your figure, and your weight becomes responsible for whether you feel well or not. At this point, dance training may no longer be viewed as a means to improve one’s technique but simply becomes another opportunity to burn calories or lose weight.

The numbers are shocking; around one third of professional dancers have a body mass index of under 17 kg/m²; more than half of female dancers do not have regular periods; two thirds are concerned about their weight. Almost half of all dance trainees and professional dancers either currently have or have had some degree of eating pathology; more than 10% suffer from an eating disorder. These numbers are considerably higher than those found in the general population, and women are more frequently affected than men.

People who do not let the thought of food dominate their lives and feel comfortable in their own skin, are much less likely to develop an eating disorder.

The high demands for bodily perfection seem to put more pressures on female dancers than on their male colleagues. Competition among women is considerably higher and the physical changes, especially during puberty, are more drastic. While young male dancers profit from their muscular growth and from being perceived as more masculine, young female dancers often struggle to adjust to their new feminine forms. They are at risk of growing uncomfortable in their own skin. If external pressure is added, this might cause some girls to change their eating habits or restrict calorie intake for gaining control over their figures. This is a dangerous behaviour because the risk of developing an eating disorder is greatest during puberty.

One speaks of ‘disordered eating’ if the person affected begins to obsess about their weight and diet. Providing information and instruction about healthy eating can help them find a path back to enjoyable and intuitively eating. But be careful: a disordered eating behaviour can lead to a full eating disorder!

An eating disorder can have severe health consequences. Other than the psychological strain, the lack of energy, building blocks and nutrients makes up an enormous strain for the body. All metabolic processes are minimized, and the body starts a process of breaking down tissue. Energy and performance abilities will significantly drop. Even after a successful therapy, eating disorders can have serious health consequences years later.

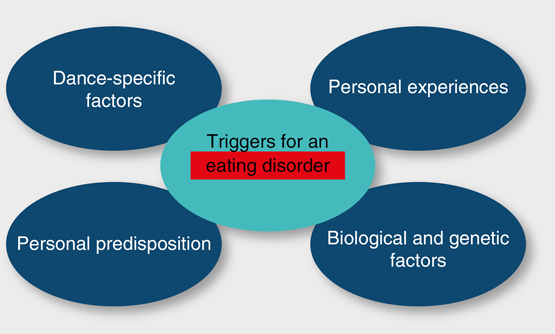

Causes, Risk Factors, Triggers

Multiple factors are at work that may encourage a dancer to develop an eating disorder: extreme slimness as a beauty ideal, high level of perfectionism, low self-esteem, and tension and competition in their professional world. These are just some of the reasons why those affected begin to reject their bodies. Eating no longer serves physical health, but rather becomes a tool for manipulation and an exercise in self-control.

Eating disorders begin in the mind! Even very slim dancers still often feel too fat or are afraid of gaining weight.

A slim, well-proportioned body may be considered the ideal in the minds of many dancers. Often, being slim is regarded as equivalent to being attractive, happy, and successful, as well as with having the perfect dance technique. Comparing oneself to role models and other dancers while constantly checking one’s own image in the mirror makes it difficult to be happy with one’s body. Young female dancers in particular tend to go for different diets, and, in extreme cases, even drastically restrict caloric intake in order to attain their ideal body image. This can go very wrong, as a constant concern for eating can take on its own momentum. Diets become more and more controlled and restricted, and eating loses its natural quality.

Comments about one’s figure, such as criticism from a teacher, choreographer, or colleague, can become triggers. ‘Your bottom is too big’ will be translated as ‘your body doesn’t fit in; you don’t fit in here.’ Such thoughts can amplify the urge for weight control, satisfying the need to have a sense of command over one’s own body. The inner argument is: ‘If I cannot improve my dance technique to the extent I would like, I will, at least, gain control of my weight and my body.’ Little by little, the dancer may get thinner and thinner…

Today we know that, aside from the external factors, genetic predispositions can also play a role in the development of an eating disorder, as do someone’s personality and temperament. People developing eating disorders are often very ambitious, perfectionists, tough, and determined. They are very productive and want to be the best. These are qualities widely celebrated in the dance world and which are further encouraged in professional dance education.

Diagram 6.4:Many factors contribute to eating disorders

A model modified according to Wunderer/Schnebel, 2008.

The obvious question is, why are there so many eating disorders present in the world of dance? Is it that dance attracts and accommodates people with a higher risk for eating disorders or does the dance world and its competitive atmosphere create psychological stress which promotes the development of eating disorders? A question that needs to be further investigated for the wellbeing of all dancers.

Is This Still Normal? Warning Signs of an Eating Disorder

Eating disorders do not appear overnight. They develop gradually and the transition from unusual eating habits to an eating disorder is often subtle. The most important thing is not to ignore it! Eating disorders can be life-threatening. The sooner they are recognized, the sooner professional help can be found.

Table 6.8:The following warning signals can point to an eating disorder

| Eating habits |

•Eating very little |

•Having lists of ‘forbidden’ foods, frequent dieting |

•Eating very slowly and cutting up foods |

•Chewing gum frequently |

•Taking nutrient supplements, laxatives or appetite suppressants |

•Smoking to suppress hunger |

•Avoiding eating with others |

•Disappearing after meals |

•Encouraging others to eat, but not actually eating |

•Frequent visits to the toilet |

| During training |

•Not enjoying dancing |

•Low energy, tiredness (empty gaze) |

•Reduced ability to perform, and lack of concentration |

•Difficulties orientating oneself and slow reactions |

•Always more hardworking than others |

•Extreme physical activities in addition to dancing (running, gym, etc.) |

•Hiding the body with multiple layers of clothing or wide-fitting garments |

| Bodily indications |

•Body mass index (BMI) <17.5 |

•No periods |

•Frequent injuries (attention: stress fractures, see p. 125) |

•Regularly feeling cold |

•Bluish hands and feet |

•Circulatory problems and dizziness |

•Stomach pains and digestive problems |

•Dry skin |

•Loss of hair |

| The more of these criteria that you say ‘yes’ to, the higher your risk for eating disorders: | ||

| I almost exclusively think about eating, about my figure, and about my weight | ❏Yes | ❏No |

| I have the feeling that almost everyone around me is thinner than I am | ❏Yes | ❏No |

| I know the amount of calories in almost any meal or drink | ❏Yes | ❏No |

| What and how much I eat is one of the few things I can determine myself | ❏Yes | ❏No |

| I am constantly afraid of eating too much and getting fat | ❏Yes | ❏No |

| My most important goal is a perfect figure | ❏Yes | ❏No |

| I am convinced that I will be happy once I am thin | ❏Yes | ❏No |

| My weight determines whether or not I feel well | ❏Yes | ❏No |

| I never feel hungry | ❏Yes | ❏No |

| When I feel full after a meal, I feel bad | ❏Yes | ❏No |

| I associate eating with fear and a guilty conscience | ❏Yes | ❏No |

| After eating, I frequently throw up | ❏Yes | ❏No |

| I feel uncomfortable when eating around others | ❏Yes | ❏No |

| I often feel sad and am afraid I will never find a way out of this | ❏Yes | ❏No |

| I feel like I constantly have to meet high demands | ❏Yes | ❏No |

Modified according to Mikyskova, 2013.

No form of eating disorder is compatible with a healthy career in dance. Eating disorders can lead to significant health problems and even be life-threatening. Dividing eating disorders into different categories serves our better understanding, yet the borders are fluid.

Anorexia in High-Intensity Sports – Anorexia Athletica

Anorexia athletica is regarded as a special form of restrictive eating behaviour among athletes in sport with a strong emphasis on aesthetics and weight, which includes dance. The reduction of weight is pursued with the goal of improving one’s physical performance or in order to increase one’s chances in the job market or during one’s schooling. In spite of having low body weight, people with this condition maintain, or even improve, their abilities to perform. Yet, anorexia athletica is a balancing act between a restricted diet and an eating disorder. Trainers, teachers, and parents should be especially aware of signs that could indicate a shift towards an eating disorder.

Pathological healthy eating – Orthorexia Nervosa:

Those affected strictly divide foods into ‘good’ and ‘bad’. Only ‘good’ foods are eaten and ‘unhealthy’ foods rigorously avoided. Going out to dinner quickly becomes very complicated, thus social isolation is a common symptom. Often, there is a high missionary desire to convert others to their own ‘healthy’ way of eating.

The typical sign of anorexia is an extreme loss of weight effected by the person, themselves. The word ‘anorexia’ comes from the Greek word ‘anorektein’, which means ‘without appetite’. Yet, those affected do not lack appetite, but intentionally suppress their appetite. Anorexic dancers weigh too little for their age and height or do not gain enough weight, in spite of growing older and taller. Their body fat percentage drops (see p. 120), and often individual bones and tendons become visible. By those suffering from anorexia this is often viewed as a sign of success – a dangerous perspective. Anorexia occurs often in adolescence, and is around three times as frequent among dancers as it is in the general population. This illness is life-threatening, and even lethal for 6% of all anorectic patients!

Table 6.9:Signs of anorexia

•Body mass index <17.5 kg/m² (in adults), or being in the ‘severely underweight’ section on the growth curve (among children and adolescents, see p. 118). |

•Intentional weight loss |

•Pathological perception of self: in spite of being extremely thin, one regards one’s own body as fat |

•Absence of monthly period |

•Growth disturbances |

The word ‘bulimia’ comes from two Greek words, ‘bous’ for ox, and ‘limos’ for hunger. This ‘ox-hunger’ is associated with the primary symptom of bulimia: eating attacks. Those affected suffer from eating attacks several times a week, which means they eat large amounts of food in short periods of time. In order to ‘undo’ the high amount of calories ingested and to prevent weight gain, they regurgitate the food or take laxatives in an attempt to eliminate food from the body. Those suffering from bulimia invest a lot of time and money in buying enough groceries for their hunger attacks; eating attacks and the counteractive methods taken must be kept secret, which can lead to social isolation. Unlike those suffering from anorexia, people with bulimia are rarely underweight, making it doubly difficult to recognize this eating disorder. Most cases occur between the ages of 18 and 25. It is estimated that up to 10% of dancers suffer from this disorder.

Table 6.10:Signs of bulimia

•Constant preoccupation with food. Regular eating attacks, where large amounts of food are ingested in short periods of time |

•Actions taken to counteract the large amounts of calories ingested include intentional regurgitation, taking laxatives, appetite suppressants, and other medication |

•Pathological fear of getting fat and having a clearly defined, very low maximum weight limit |

When There Is Cause for Concern – Dealing with Eating Disorders

Dance teachers and colleagues are often the first to notice when a dancer is getting too thin. It is important not to wait too long, and take the first steps quickly. An eating disorder is not a ‘bad phase in life’, it is a disease that can be life-threatening. It cannot be controlled by a few dietary tips, but requires professional treatment.

The earlier treatment begins, the better the chances of healing!

Tips

✓Read up on inpatient and outpatient centres and individual practitioners licensed to address eating disorders, whose contact details you can pass on.

✓In order to consolidate your impressions and suspicions, it is advisable to share your concerns with others. Ask the opinions of your colleagues and/or other dancers. This can help to verify your suspicions.

✓If the suspicions seem justified, a trusted person should speak individually and privately to the dancer. Do not give a diagnosis, nor any tips on nutrition. Do not try to assume the role of the therapist, but communicate that you have observed changes and are concerned.

✓Do not be afraid of reactions. The dancer might negate or harshly dispute your suspicions. Be prepared for this so you can deal with the situation more easily. Follow your intuition.

✓Offer information about eating disorder counselling services. Even if it is rejected at first, it can still be the first step to treatment.

✓If the dancer is underage, contact the parents, but not without first informing the child of your intentions. Offer the parents the contact information of counselling services.

Avoiding Eating Disorders – Tips for the Dance World

The frequent rate of eating disorders among dancers is not only due to dance. Yet, there are some habits and procedures in the dance world which should be critically examined as they are seen to encourage unhealthy eating behaviour and can trigger the development of eating disorders.

Whether being a dance teacher, a professional dancer or an older dance student, role models play an important role in the development of young dancers. Dance teachers should, therefore, be aware of their function as a role model for healthy attitudes towards weight and body image. They should think about the following questions:

•How do I see my own body and figure?

•What is my ideal of the perfect dancer’s body?

•What do I think about dancers who do not comply with this ideal figure?

•To what extent do I allow or even encourage competitiveness among the dancers?

•Do I comment on my students’ bodies, weights, and figures in front of others?

Daily training in front of the mirror promotes a critical look at one’s own body. It is necessary to learn healthy ways of working with a mirror. It can be frustrating if one’s mirror image does not correspond to one’s own ideal. For that reason, every dancer should ask themselves:

•Do I use the mirror deliberately?

•How intensively do I use my inner perception of my body and my movements, and how much do I rely on the image in the mirror?

Assessing Dance Technique, Not Body Figure

Be careful about comments on figure and weight! Whether it is meant as praise or criticism, every comment can strike a sore point and, thus, become a trigger for exaggerated weight loss and unhealthy eating habits. Inapt comments or thoughtless remarks can trigger the fear of getting fat, even in slim dancers; comments about changes in figure or weight should only take place in private. Be careful when choosing your words! Assessing somebody’s figure in a dance examination by assigning a grade is no longer acceptable. One should evaluate a dancer based on their technical and artistic progress, not based on their figure.

No public control of weight, such as weighing in front of the group! If there is a weight problem, this should be discussed in a one-to-one meeting. If necessary, a registered dietitian should be consulted to provide supportive strategies. There should not be any threats of sanctions for too much weight gain, such as taking away a dancer’s role in a performance.

We can no longer afford eating disorders to be a taboo in dance! If there is a suspicion that someone is suffering from an eating disorder, then a quick reaction can save a life. Every professional school and every company should develop strategies for dealing with eating disorders.