CHAPTER 5

Motivating Elements: Course Policies, Communications, Assessments, and More

The more that instruction supports a positive attitude and maintains student interest and utility value for course goals and student self-efficacy for the course by convincing students that they are capable of achieving the learning and performance goals of the course, the more students will persist when environmental events distract them.

—R. E. Clark (2004)

MOTIVATION, EFFORT, AND ACHIEVEMENT

MOTIVATION, EFFORT, AND ACHIEVEMENT

Recall that one of the seven learning principles that Ambrose, Bridges, DiPietro, Lovett, and Norman (2010) proposed focuses on student motivation, specifically on how it determines how much effort and perseverance students will invest in their learning. The online learning literature emphasizes motivation just as much for its impact on course completion and outcomes achievement (Clark, 1999, 2004; Noesgaard & Ørngreen, 2015; Stöter, Bullen, Zawacki-Richter, & Prümmer, 2011). After all, instructional materials make no difference if the student is not motivated to use them and learn (Ally, 2004). Unmotivated students are more likely to drop out, but you can change their attitudes by using intentional motivation strategies (Hartnett, St. George, & Dron, 2011; Woodley & Simpson, 2014). Do not assume you will not have to motivate your online students just because they are more mature than traditional-age classroom students. We have no evidence that online students have greater self-motivation.

The impact of motivation in online learning has remained strong over many years. In fact, in a web-based learning study by Shih and Gamon (2001), students’ motivation explains more than 25 percent of their achievement. Many other studies show how motivation factors into success (or failure), as well as persistence, in online courses. For example, Lee and Choi’s (2011) meta-analysis of the research from 1999 through 2009 reveals that covariants of motivation—including self-efficacy, goal commitment, and satisfaction—affect online course completion. Hart’s (2012) review of twenty studies published between 2001 and 2011 finds that motivated students persist in online courses in spite of obstacles. The mediating variables she identifies include student satisfaction and a sense of belonging to the learning community. Many studies confirm that faculty can enhance student motivation and improve student performance by adding particular motivation strategies to online courses (Chang & Chen, 2015; Chang & Lehman, 2002; Chyung, Winiecki, and Fenner, 1999; Hu, 2008; Keller & Suzuki, 2004; Kim & Keller, 2007; Marguerite, 2007; Park & Choi, 2014; Robb & Sutton, 2014; Visser, Plomp, & Kuiper, 1999; Zammit, Martindale, Meiners-Lovell, & Irwin, 2013; additional studies cited by Keller, 2016).

Mediating between motivation and academic success are the choices students make and the effort they exert in pursuing a goal (Hu, 2008). In predicting success, Firmin et al. (2014) find that “measures of student effort eclipse all other variables examined, including student demographic descriptions, course subject matter, and student use of support services” (p. 189). Fortunately, most of the motivators overlap with some of the principles of learning that the previous chapter addressed and the quality of student-content, student-instructor, and student-student interactions that we address in the next chapter. Thus, many facets of good teaching serve both to motivate and facilitate cognitive processing and memory.

This chapter examines the research on how course policies, communications, activities, assignments, assessments, feedback, and grading can enhance student motivation (Hoskins & Newstead, 2009; Nilson, 2016). Furthermore, it links the motivating factors to various theories of motivation:

- Behaviorist; goal setting (Locke & Latham, 1990)

- Goal expectancy (Wigfield & Eccles, 2000)

- Self-determination (Deci & Ryan, 1985, 2002)

- Social belonging (see chapter 6)

- ARCS—Attention, Relevance, Confidence, and Satisfaction (Keller, 2000, 2008a, 2008b, 2010, 2011, 2016)

ARCS incorporates elements of other theories, such as Bandura’s self-efficacy (1977a, 1977b), Berlyne’s curiosity and arousal (1960, 1965, 1978), Maslow’s needs hierarchy (1954), McClelland’s achievement motivation (McClelland & Burnham, 1976), Rotter’s locus of control (1975), and Seligman’s learned helplessness (1975). We will mention relevant causes of persistence in online courses because it is a by-product of motivation.

TOO MUCH OF A GOOD THING?

TOO MUCH OF A GOOD THING?

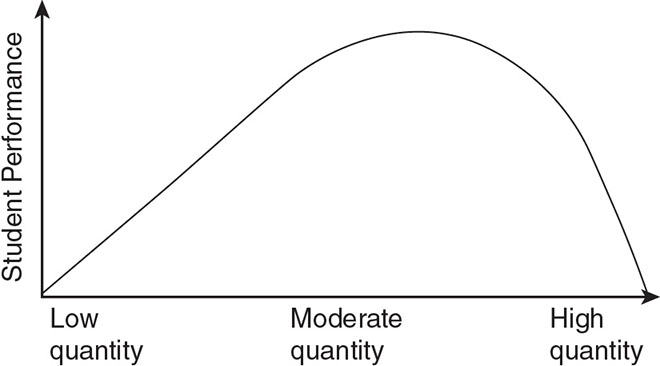

According to the research we have already cited, learning requires ongoing motivation, and deliberately adding motivational strategies improves students’ motivation to learn and their pass rate in online courses. But a qualification is in order: you can overdo such strategies and both fail to motivate disinterested students and distract the already motivated ones (Huett, Kalinowski, Moller, & Huett, 2008; Keller, 2010). You must strike a balance to avoid too much of a good thing and select the types and quantity of motivational strategies that will work best with your online students. For instance, sending out multiple motivational messages every week numbs students to your message and may even annoy them. The same holds true with your interactions with your students. Figure 5.1 illustrates the curvilinear relationship showing that motivational strategies and interactions with your students enhance student learning and performance only up to a point.

Figure 5.1 Impact of Quantity of Instructor-Initiated Motivational Contacts on Student Performance

CATEGORIES OF MOTIVATORS: INTRINSIC AND EXTRINSIC

CATEGORIES OF MOTIVATORS: INTRINSIC AND EXTRINSIC

First, we distinguish between intrinsic and extrinsic motivators and review the research on their relationship to each other. Intrinsic motivation is based on one’s interest in the task or subject matter. The driving force behind it is enjoyment, curiosity, fascination, creative outlet, satisfaction, or a sense that the task or subject matter is relevant. Extrinsic motivation is anchored in the expectations of a reward outside of the task and subject matter—earning a good grade, getting money, pleasing or impressing someone else, getting out of unwanted responsibilities, and the like.

After conducting research on children, Kohn (1993) made headlines claiming that extrinsic rewards like grades reduce intrinsic motivation. However, additional evidence supports other conclusions. According to Svinicki (2004), a person has to be intrinsically motivated before extrinsic motivators can have an impact. But consider this: Does the fact that you get paid for teaching make it less appealing to you? No, and probably the contrary. Confirming our personal experience, other researchers find that extrinsic rewards have either no effect or a positive effect on intrinsic motivation (Cameron & Pierce, 1994; Eisenberger & Cameron, 1996). Still others forward evidence that the two types of motivators have an interactive curvilinear relationship in which moderate extrinsic motivation coupled with high intrinsic creates the optimal motivation (Lin, McKeachie, & Kim, 2001). Other positions argue that autonomy of action overrides intrinsic-extrinsic distinctions (Rigby, Deci, Patrick, & Ryan, 1992; Ryan & Deci, 2000) and that intrinsic motivation simply does not exist (“Intrinsic Motivation Doesn’t Exist, Researcher Says,” 2005).

Related studies have tested the effects of performance goals—that is, the desire to appear competent to others. While performance-avoidance goals (to avoid looking incompetent) do seem to undermine motivation, research yields mixed results on the effects of performance-approach goals (to look competent) on both motivation and performance (Urdan, 2003).

In summary, the literature on intrinsic and extrinsic motivation comes to no clear conclusions.

REINFORCING AND PUNISHING

REINFORCING AND PUNISHING

Behaviorism classifies the motivators differently. While the theory applies to complex animals including humans in all contexts, we explain it here in a human learning context (Lysakowski & Walberg, 1981; Schunk, 2012). Behavioral psychology proposes two types of reinforcement as powerful shapers of behavior. In the positive variety, students’ behaviors reward them with something they want, and in the negative type, their behaviors help them avoid something they do not want. The reinforcement, whether positive (getting something good) or negative (avoiding something bad), makes them more likely to repeat the behavior. Punishment has the opposite effect: it makes students less likely to repeat the punished behaviors. In one type of punishment, students get something they do not want, and in the other type, they are deprived of something they do want. Punishment may teach students what not to do, but it tells them nothing about what they should do.

Reinforcement and punishment generally pertain to extrinsic motivators and demotivators. Except by terrible teaching, how could we remove a student’s enjoyment, curiosity, fascination, creative outlet, satisfaction, or a sense of relevance from a task or subject matter? And why would we? Applying behaviorism rests on determining what extrinsic results students do and do not want. All around the world, the educational system regards grades as the universal student currency, but even they do not always motivate and often are not sufficient. For example, some students’ reasons for taking online courses may have little to do with learning or grades. Clearly, establishing reinforcement depends on correctly identifying what students really want or really want to avoid, and not always what we guess would be a reinforcement. The same applies to punishment.

This is not to say that were it not for our institutional obligation to give grades, we should abandon behaviorism in teaching. Lewes has applied it very effectively in her face-to-face English classes using token amounts of money to reward—in effect, positively reinforce—her students for class participation (Lewes & Stiklus, 2007). Her success teaches us that giving students extrinsic rewards and positive reinforcement may be necessary to get them to interact with the material. Once they do, they may find intrinsic value or positive reinforcement in learning the subject matter. If they do discover value in the material or find learning it enjoyable, then learning becomes its own reward and intrinsic motivator.

Recent psychological research has moved away from studying behaviorism and the relationship between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Both psychology and instructional design have been cutting the pie differently and focusing more on factors related to interest, goals, self-efficacy, choice, autonomy, achievement, and social needs.

CAPTURING ATTENTION

CAPTURING ATTENTION

In online courses, gaining and sustaining attention ranks as the top priority (Ally, 2004; Keller, 2000; Liao & Wang, 2008). Student attention precedes motivation, engagement, and learning. A primary attention-getting strategy, one well known in the classroom context, is your demonstration of enthusiasm, animation, energy, and dynamism (Nilson, 2016). For simple survival, the human mind is well adapted to shift its attention to movement, change, intensity, and the human face. Online, you can display these emotions in recorded lectures using a variety of nonverbal communication techniques: constant eye contact with the audience, vocal variety in pitch and speaking pace, dramatic pauses around important statements, changes in facial expression, smiling, gesturing, and moving around the recording area as much as the technology allows. The most effective recording software can display both the instructor speaking and other visuals (e.g., pictures, presentation slides, animations) at the same time, and you can add visual close-ups when detail matters, such as when demonstrating procedures or showing parts of a larger whole.

You can begin expressing your enthusiasm from the beginning of the course. For example, in introducing yourself and your course, your words and images can convey your passion and enthusiasm for the value of what you teach and your teaching process (Hew, 2015). You set the tone and climate at the outset with those “opening moments” (Dennen & Bonk, 2007). You can share your own past efforts, struggles, and successes in mastering the same material you are now teaching (Anderson, 2004). (Alternatively, you might reserve such sharing until your students experience similar difficulties.) You can start conveying your enthusiasm even before the semester starts. As soon as your course site is accessible to students, you might receive e-mail inquiries from them. In such cases, you can build the rhetoric of social presence when you respond by opening with a personal greeting, thanking the students for initiating contact, and expressing concern for their learning (Ley & Gannon-Cook, 2014). Your active presence is itself a major motivating factor for your students (Funk, 2007; Moore, 2014). It shows you care, and when students know you care, they are more likely to want to persist in your course (Robb & Sutton, 2014).

Of course, establishing your enthusiastic presence goes beyond the initial introduction. You can communicate it in your virtual online office, your announcements, and the motivational e-mails you can send out (we will say more about such e-mails in a later section), as well as in everyday e-mails, text messages, tweets, and Facebook notifications (Woodley & Simpson, 2014).

Aside from projecting an enthusiastic, dynamic persona, you can attract and maintain class attention by arousing students’ curiosity and integrating plenty of variety into your lessons. In fact, you can do both at the same time using these techniques (Keller, 2000, 2008a, 2008b, 2010, 2011, 2016):

- Introducing facts and insights that are surprising, intriguing, novel, or unexpected

- Drawing students into an inquiry with interesting puzzles, paradoxes, challenges, questions, problems, incongruities, and dilemmas

- Offering diverse examples and models

- Incorporating a wide range of activities (e.g., worksheets, cases, academic games, role plays, simulations, discussions, debates)

- Varying presentation modalities (audio, graphics, video, animation, text, and multimedia)

This last technique deserves elaboration. We know that students appreciate media beyond text and discussion (Bolliger, Supanakorn, & Boggs, 2010). Hearing your voice on a podcast, for example, helps students feel more connected to you as long as your podcasts are short enough to keep their interest. Bringing in guest speakers in synchronous or asynchronous sessions can also gain students’ attention, as well as offer them diverse perspectives and foster their curiosity. Just displaying appealing materials activates student attention. Whatever their medium, they can stimulate interest, attract the eye, and facilitate listening (Fahy, 2004; Mayer, 2014).

Presentations typically give you your first opportunities to direct student attention to the course itself, and we know that attractive features give rise to positive feelings. These feelings include students’ perceptions that attractive online instructors have greater expertise (Liu & Tomasi, 2015; Norman, 2005), so try to look your best in your videos. In one study (Hu, 2008), student motivation increased when the course site interface was visually improved with different background colors, a more professional look and layout, and better graphic design elements (larger headings, Arial font, and color coding). (See also Clark & Lyons, 2011.) In addition, introducing a new lesson with an advance organizer and an engaging title makes a favorable impression on students (Lidwell, Holden, & Butler, 2010; Norman, 2005; Sankey, 2002; Tomita, 2015).

As part of her strategy to gain and keep student attention, Linda Lolkus put substantial effort into developing clever titles and colorful, uplifting images she used in her summer online nutrition course. She put these on the covers of the weekly course folders, supplementing the high expectations she expressed for her students and the overview of the topics she provided for the week (Goodson, 2016b).

- Week 1. Get Real! Get Ready! Chapters 1 and 2—happy woman with grocery bag of fresh colorful vegetables

- Week 2. Stacking Up! Chapters 3 and 4 and Exam 1—slices of bright fruits stacked on top of each other

- Week 3. With Body in Mind! Chapters 5 and 6, Exam 2—fit and trim body doing a sit up while holding an apple in one hand

- Week 4. Inside Insights Chapters 7, 8, 10, and 11—colorful foods arranged over a front-facing silhouette in the shape of internal organs

- Week 5. Seize the Day! Exam 3 and Chapters 9 and 15—young fit parents holding a healthy happy baby

- Week 6. The Time of Your Life! Chapter 16 and Exam 4—clock with old-fashioned round brass alarm bells.

Attracting and maintaining attention opens your students’ minds to your course material, an essential first step toward motivating students to learn. We turn now to other motivators and strategies that achieve the same goal.

ENSURING RELEVANCE

ENSURING RELEVANCE

Even if you attract your students’ attention, you will not be able to maintain it if they fail to see the relevance of your material to their lives. To bother to engage with the online content, they have to perceive value in it (Hart, 2012; Keller, 2000; Liao & Wang, 2008; Park & Choi, 2009), so you have to ensure that students connect the material to their past and current experiences, their personal goals, and their visions of their future. Keller suggests three approaches to ensuring relevance—making connections, setting meaningful goals, and using student interests—and we consider these first (2000, 2008a, 2008b, 2010, 2011, 2016).

Making Connections

Use metaphors, examples, stories, comparisons, and contrasts to link the subject matter to something students already know, whether through their earlier experiences or their prior learning. In addition to supplying students with these connections, ask students for examples and for ways they anticipate using the new skills and knowledge. Help them see how they can transfer their skills to other courses and work situations. Paraphrase the content in everyday, concrete language and different communication modalities (audio, graphics, video, animation, text, and multimedia). Explain how your field fits into the big picture and how it contributes to society.

Setting Meaningful Goals

A second approach is to help students identify or select useful and meaningful goals. Some of your students will not have goals, and you may have to help them focus their attention on their future, identify a goal, organize their effort toward it, and develop and follow strategies to reach it (Koballa & Glynn, 2007). You can offer examples of goals and explain their value to students’ lives in the real world. Having students set a goal increases their motivation to attain it, according to goal-setting theory (Locke & Latham, 1990). Certainly, mastering some definable body of material and earning a good grade qualify as possible goals for students. This motivation in turn increases the energy, work, persistence, and thought they will give toward achieving their goals.

For this motivational approach to work, a few conditions must hold:

- Students must believe that they have freely chosen the goal, and they might not always think they have in what they perceive to be required courses. However, you can incorporate choices into your courses, such as different ways to satisfy course requirements and choices among assignments, topics, media used, and the like. Giving students options cultivates that sense of free will. We know that volition (self-regulation) helps students persist with goal-driven behaviors, like studying and completing course activities (Zammit, Martindale, Meiners-Lovell, & Irwin, 2013).

- They have to see the goal as specific and measurable; these are the qualities typically found in a good assessment, rubric, or a grade.

- They must get feedback about their progress toward the goal and ways they improve in their course work.

- Students must size up the goal as challenging, but achievable. Difficulty does not necessarily discourage; in fact, the higher the difficulty (up to a reasonable point), the more effort a student will put toward the goal.

The research on online learning upholds the value of goal-driven activities in increasing student motivation. For example, in their study of preservice teachers in online distance learning, Hartnett, St. George, and Dron (2011) found it most important to help students clearly see the relevance and value of the learning activities and the connections between those activities and both the learning outcomes and students’ personal goals and aspirations in the short- and long-term.

When students have group goals, as they do in problem-based learning, they are more motivated to work with each other to turn out a good product. When the group completes its project, it can post its results in a whole-class forum, which also motivates high-quality work (Dennen & Bonk, 2007). Of course, such motivation depends on the students’ degree of preparation and your design of the group and discussion assignments. In any case, developing goal-oriented activities makes it less likely that other things competing for their attention will distract students.

Using Student Interests

A third strategy is to adapt the course topics, course policies, content organization, and assessments to student preferences, interests, and needs as much as possible. This increases students’ sense of free choice over their goals. People want to pursue their interests and use their capabilities (Koballa & Glynn, 2010). This preference ties in with their desire for self-determination—that is, the ability to have choice and some control in what they do and how they do it (Dennen & Bonk, 2007; Koballa & Glynn, 2010).

Therefore, let students select how to organize what they learn—for instance, to use concepts maps, diagrams, flowcharts, or outlines—and how they want to be assessed—by a paper, report, treatment plan, business plan, portfolio, website, a video, audio presentation, or something else. What would be most useful to individual students? The student’s control over the sequence of learning is also known to increase persistence (Chyung, Winiecki, & Fenner, 1999; Hu, 2008).

Several course examples illustrate this strategy:

- With motivation in mind, Anna Gibson gives her students in her online organizational leadership course the opportunity to choose the topic of the weekly discussion they will lead based on their interests (Goodson, 2016a). Using this approach might seem like an obvious strategy because of her subject matter, but you can apply it broadly whenever students can assume responsibility for leading a discussion (Anderson, 2004).

- InSook Ahn gives her students topical choices each week of her aesthetics of fashion design online course. For each discussion, she provides links to resources illustrating distinctively different types of art and fashion design. Students can choose one type as the focal point of the discussion (Goodson & Ahn, 2014). In later offerings of this course, Ahn can change the names of the artists and the links while keeping the same discussion structure and directions. In another learning activity, she lets her students find any fashion designs they like, analyze their choices, and determine the sources of their inspirations.

- In art history, Debbie Morrison offers students choices in an assignment that uses social media (Online Learning Insights, 2016). Her directions allow students to take and post photos of any art form that represents any one of seven art movements (Renaissance, Baroque, Romanticism, Realism, Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, or Modernism) from any location in their everyday lives, and she lets them post their images however they choose (such as Instagram, for which she provides instructions). She asks students to describe what movements their images represent and challenges them to post partial images with enough information that other students can identify the movements they represent.

- Integrating students’ photos into a course activity also has worked well in John LaMaster’s online math course at Purdue University Fort Wayne. He has his students find and photograph local examples of mathematical concepts as one of their online learning activities. LaMaster receives the photos by e-mail to make sure the examples are correct before adding them to the course site for all to view (Goodson, 2016c).

Explaining Your Methods

A fourth and final way to enhance the relevance of your course is to explain why you designed, organized, and developed the course the way you did. Tell students why you chose or designed the activities, readings, videos, podcasts, assignments, teaching methods, policies, and assessment strategies that you did. Students do not assume that everything you do is well considered or for their own good (Nilson, 2016), and they have no idea of the research behind your choices. In fact, their perceptions of course quality and utility have an impact on their motivation and entire online experience (Sun, Tsai, Finger, Chen, & Yeh, 2008).

Veronika Ospina-Kammerer’s course on psychopathology illustrates the power of explanation (Goodson, 2016d). After her students complained about the heavy workload, she acknowledged it and explained her reasons for the depth of work on the course topics each week and the need for students to practice high-level analysis and judgment in this field. Without missing a beat, the students continued with their hard work and fully participated in the online discussions. Their final course evaluations revealed that they had developed such a high degree of community that they had exchanged names and contact information in the student lounge area and planned to stay in touch after the semester ended.

ENCOURAGING GOAL EXPECTANCY AND SELF-EFFICACY

ENCOURAGING GOAL EXPECTANCY AND SELF-EFFICACY

Helping students set goals gives them a good start, but they also must have the self-confidence to achieve them. Expectancy theory rests on a pragmatic premise: Why aspire to achieve something you know you cannot achieve? Students will not even try to learn something that seems impossibly difficult. To set and pursue a goal, they need to believe that they have the agency and the capability. Agency depends on their sense of self-efficacy and their beliefs about the malleability of their intelligence and their locus of control. Students with low self-confidence, the fixed mind-set that their intelligence is determined by heredity, or the fatalist belief in an external locus of control have a weak sense of agency and a low expectancy of challenging goal achievement. They may also not understand what they are expected to do—a condition you change by providing clear learning outcomes, directions, and models of what you expect (Keller, 2000).

Students feel capable, confident, and self-efficacious when they view the learning task as doable within the scope of their abilities, academic background, and resources, such as time, encouragement, and assistance (Wigfield & Eccles, 2000)—that is, when they can expect success (Keller, 2000; Liao & Wang, 2008). In one study, self-efficacy, along with good time management and study strategies, distinguished students who persisted beyond three courses from those who did not persist (Holder, 2007).

The following strategies will contribute to your students’ sense of self-efficacy and their expectations for success:

- Explicitly fostering self-efficacy

- Making the path for success visible

- Providing multiple opportunities for success

- Sending motivational messages

- Sharing strategies for success

- Explaining the value of errors

Explicitly Fostering Self-Efficacy

You can explicitly foster students’ beliefs that they have the agency and capabilities to achieve. While many of today’s students have high self-esteem, they still may have a weak sense of self-efficacy. Some sailed through the K–12 system and never had to meet an academic challenge before coming to college (Ripley, 2013). They may even sabotage their own success by not studying in order to protect their self-esteem because if they do poorly, they can blame their lack of studying rather than their lack of ability. Such students may also believe that they cannot increase their intelligence.

Others may doubt that they have any real control over their academic fate. In their experience, studying and working hard seem to make little difference in their grades. They feel that they just get lucky when they encounter readings they can understand, test questions they can answer, and assignments they can handle. In their view, most of the control resides in you. They do not perceive themselves earning a letter grade; rather, they believe that you give it to them on some basis that they do not fully understand.

Moreover, students often underestimate the effort and time that a high-quality product or performance requires. Because attributing one’s success to effort is associated with high achievement, you should give praise for effort (Ley & Gannon-Cook, 2014) and encourage a growth mind-set (Dweck, 2007). A growth mind-set endorses an internal locus of control, a sense of personal responsibility for one’s own success or failure, and a belief that one’s effort and perseverance determine one’s success. Furthermore, telling students the learning outcomes of the lesson, encouraging their success, and giving them the option to use different strategies to complete it can help build student confidence (Ally, 2004).

Online students typically report their own limitations, such as getting behind in a course and not being able to get caught up, running into scheduling and time problems, and having poor computer skills or low confidence in using technology (Fetzner, 2013; Ilgaz & Gülbahar, 2015; Lee & Choi, 2011; Sun et al., 2008). For these students, you may find that motivation improves with clear start and due dates for activities and assignments, encouragement and reminders between those dates, clear directions and guidelines, and technology training and support, such as just-in-time online tutorials and access to a campus help desk.

Making the Path for Success Visible

Students must be able to see that the learning path is achievable and meaningful (Ally, 2004). You help them see their progress or lack thereof and evaluate their success when you do the following:

- Set clear goals, standards, requirements, and evaluative criteria for the assigned tasks

- Provide explicit, assessable, measurable learning outcomes (see chapter 3)

- Make assignments that ask students to reflect on their progress

You can encourage reflection by using these strategies:

- Having students write a learning analysis of their first test in which they appraise how they studied and can improve their studying

- Giving them second chances by letting them drop the lowest quiz or test score, earn back some of their lost points, or write explanations for their wrong answers to objective quiz or test items

- Telling your students about their peers from prior course offerings who have succeeded

- Preparing students for tests with practice tests containing the same types of items that will appear on the actual test and by giving them a list of the learning outcomes that they will have to perform on the test

- Designing rubrics with specific descriptions of different quality levels of the work and distributing these along with the assignments

- Providing constructive feedback emphasizing how to improve—that is, giving confirmatory, corrective, informative, or analytical feedback rather than social praise

- Specifying the criteria for success in future performance (Chyung et al., 1999)

Providing Multiple Opportunities for Success

Create plenty of opportunities for students to experience some measure of success and achievement, especially early in the course. As Benjamin S. Bloom once recalled, all of the great teachers have distinguished assessment for learning from assessment for evaluation (Brandt, 1979). After all, learning is a process. Strategies to support this approach include these (Nilson, 2016):

- Sequence your course outcomes, content, and skills from simple to complex or from known to unknown.

- Assign activities and tasks that build in some challenge and desirable difficulty—not too easy but not overwhelming—adjusted to the experience and aptitude of the class. Finding the right balance can be challenging, but experience will help a great deal.

- Give students the chance to reflect on their success at a challenging task to foster their self-confidence and a growth mind-set (Müller, 2008).

- Pace the course to accommodate students’ needs to help ensure their persistence (Müller, 2008).

- Give students multiple chances to practice performing your learning outcomes before you grade them on their performance.

- Use criterion-referenced grading instead of norm-referenced grading; the former system gives all the students in a course the opportunity to earn high grades.

- Provide many and varied opportunities for graded assessment so that no single assessment counts too much toward the final grade.

- Test early and often.

Sending Motivational Messages

Research on online courses shows that your strategic encouragement increases motivation, persistence, and completion rates (Chyung et al., 1999; Kim & Keller, 2008; Visser, 1998; Robb, 2010; Robb & Sutton, 2014). In an early online learning study, students’ motivation scores improved when each module ended with positive language, each correct answer yielded a congratulatory message, and each test closed with encouraging words (Chyung et al., 1999). Another study reported a variety of tactics that significantly improved student confidence, satisfaction, performance, and perception of the relevance of the material: an introductory letter expressing a personal interest in and expectation of the students’ success; shared personal information to build community and lower anxiety; clear learning requirements; reminders of success opportunities; and the assignment to design a study plan, which instills a sense of personal control and responsibility (Huett, Young, Huett, Moller, & Bray, 2008).

A related study (Huett et al., 2008) obtained similar results when the instructor sent students motivational e-mails with the following features (pp. 167–168):

Introduction.The beginning of the message contained a brief paragraph with an enthusiastic tone of introduction. For instance, “I hope you are doing great! I sent a letter out last week introducing myself and reminding you of what is expected in this class. If you are anything like me, you might have a tendency to procrastinate or a tough time getting started. Don’t worry—there is still time.” The intent of the opening paragraph was to get the learners’ attention and convey assurances of the instructor’s personal interest in learner success.

Goal Reminders.The intent of the next few paragraphs was to offer goal reminders. For instance, “Ideally, by the end of these first few weeks, you will have completed at least three or four of the SAM Office 2003 assignments” and “Don’t forget the deadline for. . .”

Words of Encouragement.The next paragraph was devoted to general words of encouragement. For instance, “As you complete the assignments this week, I would like to extend hearty congratulations to all of you for your hard work” and “You are almost done with this section of the class, so run for the finish. I have great faith in your continued success. You can do it!”

Multiple Points of Contact.The final paragraph served to assure learners and offer multiple contact points for feedback opportunities. For instance, “I am very sure you will be successful. If you ever need my help or have any questions or concerns, please do not hesitate to contact me via e-mail at [email protected]. If it is an emergency, I can be reached on my cell at 555–1234.”

In this study, the same course was taught on campus and online, with one online section receiving the motivational messages (treatment class) every two weeks and the other online section and the campus class not receiving them. In the online treatment class, students attained motivation scores equal to those of the on-campus class and significantly higher than those of the other online class. Relatedly, the failure rate in the online treatment class matched up with the campus class at about 6 percent, whereas that in the other online class approached 19 percent. The withdrawal rate in the treatment class was nearly 5 percent versus 16 percent in the other online class. These statistics show the power of simple, biweekly motivational e-mails.

In another study, Robb and Sutton (2014) used five motivational e-mail messages based on the ARCS model. These messages boosted students’ motivation to continue with the course, their perception of the instructor as caring about their success, their comfort in communicating and asking questions, and the course completion rate. Robb and Sutton sent out the first message ten days into the course with the title “Class Success” and an embedded graphic relating a goal to success. After the fourth week, they sent an online greeting card that had animation, humor, music, and a text message with advice for students who might be struggling. They sent the third message after the sixth week with an embedded graphic and text telling students how important it was for them to review the instructor’s comments on their work. Targeting the midterm date for the fourth message, they congratulated students for reaching the halfway point and added a motivational quote and a colorful graphic. Finally, they sent a fifth message after the eleventh week containing a variety of photos, congratulating students for making it so far through the course, encouraging them to work hard to finish, and reminding them of the final date for submitting their work. Here is a description of the fourth-week message:

Image on the left side: monkey with a thumbs-up signal, broad smile, holding a bunch of bananas, under a tall tree with broad green leaves.

Text next to image: Life’s detours are never easy… But hang in there… Your efforts will surely lead you to SUCCESS!

Message on right: Are you experiencing roadblocks with the assignments? If so, keep going… Don’t give up. Take time to review the posted course instructions and syllabus to overcome any detours and to get on the right track.

Cook, Bingham, Reid, and Wang (2015, p. 7) provide other examples of brief motivational messages:

Welcome: “Welcome! Taking part in this course is a great way to improve your already impressive English language skills and to share your thoughts and ideas about academic integrity with others. We hope you find the course useful and the community of learners supportive.”

Recognize and encourage: “Thank you everyone for sharing your tips and techniques for time management. Some fantastic ideas coming through here. They will be really beneficial to others on the course.”

Give further information: “You may also find the following helpful: http://www.aquinas.edu/library/pdf /ParaphrasingQuotingSummarizing.pdf.”

Clarify confusion: “The term ‘academic integrity’ is one that some people find confusing, especially if they’ve grown up hearing about ‘plagiarism’ or ‘cheating.’ The move from those phrases to a more comprehensive term such as ‘academic integrity’ is born out of a desire to describe the subject in a more positive way.”

Summarize key points: “I’ve noticed that the thing that most people are neutral or not confident about are the values that underpin academic integrity. This isn’t surprising and is one of the reasons we created this course!”

Make connections: “… and you will learn more in Week 3 about how to acknowledge sources you use in your work.”

Troubleshoot: “Sorry to hear you can’t play the video. There is a link underneath the video where you can report any problems.”

Do not underestimate the influence of your expressing confidence in your students’ abilities and efforts. In addition, you can urge students along by sending out reminders of upcoming due dates and situated prompts to encourage their timely progress on major assignments.

Sharing Strategies for Success

Share strategies and tips on the most effective and efficient ways to learn your material, including reading, studying, problem solving, time management, metacognitive, and self-regulated learning strategies (McGuire, 2015; Nilson, 2013, 2016). Many students lack basic skills such as how to focus, read carefully, take decent notes, approach problems, think critically, study effectively, and write clearly. They also underestimate the effort, concentration, and perseverance that learning and higher-level thinking involve. Without knowledge of cognitive psychology, they have little familiarity with how their minds learn, and they will tend to rely on the ineffective techniques they learned in their K–12 schooling (e.g., memorizing, practicing in one block of time, rereading text over and over, and cramming). You might wait until after the first test or graded homework assignment to bring up these learning strategies because the disappointed students will be amenable to changing their habits.

For study habits, Inkelaar and Simpson (2015) reported success using an early study tip system. After introducing the system in the first e-mail, they issued a dozen more motivational tips every week or two on topics such as how to learn, get organized, manage time, and catch up. This system, grounded in the style of Keller’s ARCS motivation model, not only helped students but also increased retention rates enough to give the campus a “positive financial return” (p. 152).

At the very least, point students to some websites that give solid, research-based advice on academic reading, note taking, studying, writing, and other college skills, such as these:

- Getting Ready, Taking In, Remembering, Output, and How to Study by Discipline: http://www.howtostudy.org

- Study Skills Guide from Education Atlas: http://www.bestfreetraining.net/?p=1309

- How to Study.com: http://www.how-to-study.com/

- Mind Tools: https://www.mindtools.com/

- Study Guides and Strategies: http://www.studygs.net/

- Study Skills Information (Checklist and Strategies): https://ucc.vt.edu/academic_support/study _skills_information.html

- How to Get the Most Out of Studying (videos from Samford University): http://www.samford.edu /departments/academic-success-center/how-to-study

Students who put the recommended strategies into practice are likely to see the positive results quickly.

Explaining the Value of Errors

Finally, explain the value of errors in learning, and try to help students overcome their mistaken view of errors as failures. Not only are errors a natural part of learning, but students tend to remember what they learn through correcting their mistakes (see chapter 4).

CREATING SATISFACTION

CREATING SATISFACTION

Satisfaction encompasses several related motivators: a sense of achievement, perceived autonomy, felt competency, and being rewarded. Research tells us that students’ satisfaction with an online course increases their learning and their likelihood of completing the course (Hart, 2012; Ivankova & Stick, 2007; Kuo, Walker, Belland, & Schroder, 2013; Levy, 2003, 2007; Müller, 2008; Park & Choi, 2009). This makes sense. Apart from circumstances beyond anyone’s control, why wouldn’t a student stay with a course that gives him or her a sense of satisfaction?

As a motivating factor, satisfaction has roots in self-determination theory, which posits a set of built-in human needs that motivate action and achievement (Deci & Ryan, 1985, 2002). People have an innate need to grow, develop, and attain fulfillment as a person. But in order to grow and be fulfilled, they must believe they have these three qualities:

- Competence, which requires that they master new knowledge and skills and live through new experiences

- Relatedness, which means feeling attached to others, valued by them, and integrated into a social group

- Autonomy, which is the sense that they can freely choose and are in control of their own goals, outcomes, and behavior

Therefore, the conditions that help students meet these needs should foster motivation. The many course characteristics and instructor behaviors described in the rest of this section help create these favorable conditions (Keller, 2000, 2008a, 2008b, 2010, 2011, 2016; Nilson, 2016).

Let us consider now all of the factors that we know increase student satisfaction with an online course. Students must feel that the work they have invested in the course is appropriate and worthwhile, which is more likely when the course gives them opportunities to apply what they learn in real-life situations, offers significant learning (see chapter 2), and is coherently aligned (see chapter 3) (Ally, 2004; Kauffman, 2014). The relevance of the content and skills they are learning contributes to their sense of competency and achievement. Therefore, you should do the same things that ensure the relevance of your content (see the previous section):

- Explain the hidden value of learning tasks that are not obviously interesting, useful, and worth the effort.

- Bring learning into the real world with practical examples, simulations, and activities that focus on application and real problem solving.

- Design authentic, useful assignments and activities that give students practice in their future occupational and citizenship activities, such as conducting research, crafting business-related plans and reports, constructing a persuasive argument, and developing a new product.

- Encourage students to share practical ideas and real-life examples, and provide testimonials from previous students about the value of your course.

- Offer options and choices, which both foster your students’ sense of autonomy and increase the relevance of the material. Consider allowing a choice of activities, assignments, and content organization and even some input into course content and policies.

- Request and pay attention to their feedback about the course and your teaching.

Other factors that contribute to student satisfaction include these:

- The quality of the content, the course design, and the use of a variety of assessment methods (Barbera, Clara, & Linder-Vanberschot, 2013; Ilgaz & Gülbahar, 2015; Park & Choi, 2009; Sun, Tsai, Finger, Chen, & Yeh, 2008), all of which augment students’ feelings of competence

- Instructor-generated video content (Draus, Curran, & Trempus, 2014), which builds relatedness

- The quantity and quality of communication and the variety of interaction tools and activities (Ilgaz & Gülbahar, 2015), which also foster relatedness

- The instructor’s attitude toward online learning and the flexibility built into the course (Sun et al., 2008), which enhance a sense of competence

- Student comfort and perceived efficacy with the technology (Alshare, Freeze, Lane, & Wen, 2011; Chang et al., 2014; Henson, 2014; Liaw, 2008; Sun et al., 2008), which also increase feelings of competence

In addition, students are more likely to experience satisfaction under these conditions:

- When they receive recognition (positive feedback) from their instructor and peers, which enhances their sense of competence and relatedness

- When they feel that they have been treated fairly, which increases their sense of autonomy

- When they have evidence of their success, which makes them feel competent

Not surprisingly, some of the opposite conditions are known to undermine satisfaction: poor computer skills, poor time management strategies, and family stressors (Park & Choi, 2009; Willging & Johnson, 2009), as well as a lack of access to the instructor, insufficient feedback, and the instructor’s low expectations of students (Hawkins, Graham, Sudweeks, & Barbour, 2013; Herbert, 2006; Müller, 2008). Clearly, some factors under the instructor’s control can mitigate against these satisfaction detractors, including explicit, just-in-time directions; a week-by-week organization of topical units and modules; posting of due dates and reminders about activities and assignments; and situated prompts to encourage students’ timely progress on major assignments (Park & Choi, 2009; Willging & Johnson, 2009). All of these make students feel more competent. We explore relatedness in the next section on social belonging and do so in much greater detail in the next chapter.

FOSTERING SOCIAL BELONGING

FOSTERING SOCIAL BELONGING

Online learning can be lonely. Students can feel isolated when they spend hours studying all alone and interacting only with a computer (Kauffman, 2015). We must help them overcome these feelings by integrating well-designed, meaningful interactions with us and other students. Social belonging, relating to others, and feeling part of a community are so critical to student success and persistence (Croxton, 2014) that most of the next chapter recommends ways to build social interaction and community into a course. Therefore, we touch only briefly on the topic here.

At the start of the online learning process, student-instructor interactions correlate with higher learner satisfaction, and students with weak skills need more individual attention (Funk, 2005). Virtual online office hours, where the entire class can post questions and comments, also help students feel more connected (Major, 2015). Deliberately designed cohort- and team-based learning experiences foster a sense of belonging to a learning community (Bocchi, Eastman, & Swift, 2004). The positive effects of social support have proven particularly strong among ethnic minorities and first-generation students (Cox, 2011; Dennis, Phinney, & Chuateco, 2005; Jackson, Smith, & Hill, 2003).

However, students must be able to perceive this support for the benefits to accrue, so you must be explicit in expressing it (Dennis et al., 2005). When they don’t perceive this support or when the interactions seem forced rather than meaningful, such as when an instructor requires an arbitrary number of discussion board postings, they feel a loss of community and are more likely to drop out of the course (Biesenbach-Lucas, 2003; Grandzol & Grandzol, 2013).

One of the most powerful strategies for building your students’ sense of social belonging and their relationship with you is to personalize your course as much as you can. Make an effort to get to know your students by asking them about their majors, interests, and backgrounds. This information will help you tailor the material to their concerns and professional goals, which in turn will make them feel a part of a learning community (Müller, 2008). In large classes, you can foster this kind of sharing in small groups.

Let your students get to know you. Share some professional and personal information about yourself. Foster open lines of communication in both directions. Explain your expectations and assessments, but also invite your students’ feedback on ways you can help them learn more effectively. Monitor your students’ participation in discussion boards and chats and their submission of assignments. Contact those who have been missing from course-related activities, expressing your concern and encouragement. Finally, help your students get to know each other by planning online icebreakers at the beginning of the course and some group activities throughout. Chapter 6 contains many more strategies.

MOTIVATING AS OUR MAJOR TASK

MOTIVATING AS OUR MAJOR TASK

While we can place students in situations and offer them experiences that foster learning, the actual process of learning ultimately goes on inside their minds. Students have to make themselves focus and reflect on these situations and experiences, sometimes for long, effortful periods of time. From this perspective, motivating students to do this is our primary job and one just as critical as creating engaging learning situations and experiences. We have clear evidence of what works to motivate online students, we know to make a balanced use of our motivational strategies, and we have models and resources to support our choices. Here are some additional resources that may help your course planning:

- (My) Three Principles of Effective Online Pedagogy, Bill Pelz (2004), a Sloan-C award for Excellence in Online Teaching recipient: https://www.ccri.edu/distancefaculty/pdfs/Online-Pedagogy-Pelz.pdf

- Speaking to Students with Audio Feedback in Online Courses, Debbie Morrison: https://onlinelearning insights.wordpress.com/2013/04/06/speaking-to-students-with-audio-feedback-in-online-courses/

- Learning to Teach Online Episodes, University of New South Wales (short, topic-focused videos): http://online.cofa.unsw.edu.au/learning-to-teach-online/ltto-episodes.

REFERENCES

REFERENCES

- Ally, M. (2004). Foundations of educational theory for online learning. In T. Anderson & F. Elloumi (Eds.), Theory and practice of online learning (pp. 3–31). Edmonton, Alberta, Canada: Athabasca University Press.

- Alshare, K. A., Freeze, R. D., Lane, P. L., & Wen, H. J. (2011). The impacts of system and human factors on online learning systems use and learner satisfaction. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 9(3), 437–461. doi:10.1111/j.1540–4609.2011.00321.x

- Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M. C., & Norman, M. K. (2010). How learning works: Seven research-based principles for smart teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Anderson, T. (2004). Teaching in an online context. In T. Anderson & F. Elloumi (Eds.), Theory and practice of online learning (pp. 273–294). Edmonton, Alberta, Canada: Athabasca University.

- Bandura, A. (1977a). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. doi:10.1016/0146–6402(78)90002–4

- Bandura, A. (1977b). Social learning theory. New York, NY: General Learning Press.

- Barbera, E., Clara, M., & Linder-Vanberschot, J. A. (2013, September). Factors influencing student satisfaction and perceived learning in online courses. E-Learning and Digital Media, 10(3), 226–235. doi:10.2304/elea.2013.10.3.226

- Berlyne, D. E. (1960). Conflict, arousal, and curiosity. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Berlyne, D. E. (1965). Structure and direction in thinking. New York, NY: Wiley.

- Berlyne, D. E. (1978). Curiosity and learning. Motivation and Emotion, 2(2), 97–175.

- Biesenbach-Lucas, S. (2003). Asynchronous discussion groups in teacher training classes: Perceptions of native and non-native students. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 7(3), 24–46.

- Bocchi, J., Eastman, J., & Swift, C. (2004). Retaining the online learner: Profile of students in an online MBA program and implications for teaching them. Journal of Education for Business, 79(4), 245–253.

- Bolliger, D. U., Supanakorn, S., & Boggs, C. (2010). Impact of podcasting on student motivation in the online learning environment. Computers and Education, 55, 714–722.

- Brandt, R. (1979, November). A conversation with Benjamin S. Bloom. Educational Leadership, 37(2), 157–161.

- Cameron, J., & Pierce, W. D. (1994). Reinforcement, reward, and intrinsic motivation: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 64, 363–423.

- Chang, C-S., Liu, E. Z., Sung H-Y., Lin, C-H., Chen, N-S., & Cheng, S-S. (2014). Effects of online college students’ Internet self-efficacy on learning motivation and performance. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 51(4), 366–377.

- Chang, M. M., & Lehman, J. (2002). Learning foreign language through an interactive multimedia program: An experimental study on the effects of the relevance component of the ARCS model. CALICO Journal, 20(1), 81–98.

- Chang, N., & Chen, H. (2015). A motivational analysis of the ARCS model for information literacy courses in a blended learning environment. International Journal of Libraries and Information Services, 65(2), 129–142. doi:10.1515/libri-2015–0010

- Chyung, Y., Winiecki, D., & Fenner, J. A. (1998, August). A case study: Increase enrollment by reducing dropout rates in adult distance education. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Distance Teaching and Learning, 97–101. ERIC (ED 422 848).

- Clark, R. C., & Lyons, C. (2011). Graphics for learning: Proven guidelines for planning, designing, and evaluating visuals in training materials. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Clark, R. E. (1999). Yin and yang cognitive motivational processes operating in multimedia learning environments. In J. van Merriënboer (Ed.), Cognition and multimedia design (pp. 73–107). Herleen, Netherlands: Open University Press.

- Clark, R. E. (2004). What works in distance learning: Motivation strategies. In H. O’Neil (Ed.), What works in distance learning: Guidelines (pp. 89–110). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishers.

- Cook, S., Bingham, T., Reid, S., & Wang, L. (2015). Going massive: Learner engagement in a MOOC environment. Higher Education Technology Agenda. Retrieved from https://www.caudit.edu.au/system/files/Media%20library/Resources%20and%20Files/Presentations/THETA%202015%20Learner%20engagement%20in%20a%20MOOC%20environment%20-%20S%20Cook%20T%20Bingham%20S%20Reid%20and%20L%20Wang%20-%20Full%20Paper.pdf

- Cox, R. D. (2011). The college fear factor: How students and professors misunderstand one another. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Croxton, R. A. (2014, June). The role of interactivity in student satisfaction and persistence in online learning. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 10(2), 314–325.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York, NY: Plenum.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (Eds.). (2002). Handbook of self-determination research. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

- Dennen, V. P., & Bonk, C. J. (2007). We’ll leave the light on for you: Keeping learners motivated in online courses. In B. H. Khan (Ed.), Flexible learning in an information society (pp. 64–76). Calgary, Alberta, Canada: Idea Group.

- Dennis, J. M., Phinney, J. S., & Chuateco, L. I. (2005). The role of motivation, parental support, and peer support in the academic success of ethnic minority first-generation college students. Journal of College Student Development, 46, 223–236.

- Draus, P. J., Curan, M. J., & Trempus, M. S. (2014). The influence of instructor-generated video content on student satisfaction with and engagement in asynchronous online classes. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 10(2), 240.

- Dweck, C. S. (2007). Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York, NY: Random House.

- Eisenberger, R., & Cameron, J. (1996). Detrimental effects of reward: Reality or myth? American Psychologist, 51, 1153–1166.

- Fahy, P. J. (2004). Media characteristics and online learning technology. In T. Anderson & F. Elloumi (Eds.), Theory and practice of online learning (pp. 137–171). Edmonton, Alberta, Canada: Athabasca University Press.

- Fetzner, M. (2013). What do unsuccessful online students want us to know? Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 17(1), 13–27. Retrieved fromhttp://sloanconsortium.org/publications/jaln_main

- Firmin, R., Schiorring, E., Whitmer, J., Willett, T., Collins, E. D., & Sujitparapitaya, S. (2014). Case study: Using MOOCs for conventional college coursework. Distance Education, 35(2), 178–201. doi:10.1080/01587919.2014.917707

- Funk, J. T. (2005). At-risk online learners: Reducing barriers to success. eLearning Magazine. Retrieved from http://elearnmag.acm.org/featured.cfm?aid=1082221

- Funk, J. T. (2007). A descriptive study of retention of adult online learners: A model of interventions to prevent attrition (Order No. 3249896). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global (304723480. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/openview/e6183a94ca54e333bab714da3b8d6870/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

- Goodson, L. A. (2016a). Course review: BUS W430 Organizations and Organizational Change: Leadership and Group Dynamics. Instructor: A. Gibson, Indiana University-Purdue University Fort Wayne.

- Goodson, L. A. (2016b). Course review: FNN 30300 Essentials of Nutrition. Instructor: L. L. Lolkus, Indiana University-Purdue University Fort Wayne.

- Goodson, L. A. (2016c). Course review: MA 15300 Algebra and Trigonometry I. Instructor: J. LaMaster, Indiana University-Purdue University Fort Wayne.

- Goodson, L. A. (2016d). Course review: SOW 5125 Psychopathology. Instructor: V. Ospina-Kammerer, Florida State University.

- Goodson, L. A., & Ahn, I. S. (2014). Consulting and designing in the fast lane. In A. P. Mizell & A. A. Piña (Eds.), Real-life distance learning: Case studies in research and practice (pp. 197–220). Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

- Grandzol, C. J., & Grandzol, J. R. (2010). Interaction in online courses: More is not always better. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 13(2), 1–18.

- Hart, C. (2012). Factors associated with student persistence in an online program of study: A review of the literature. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 11(1). Retrieved from http://www.ncolr.org/jiol/issues/pdf/11.1.2.pdf

- Hartnett, M., St. George, A., & Dron, J. (2011, October). Examining motivation in online distance learning environments: Complex, multifaceted, and situation-dependent. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 12(6). Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/1030/1954

- Hawkins, A., Graham, C., Sudweeks, R., & Barbour, M. K. (2013). Course completion rates and student perceptions of the quality and frequency of interaction in a virtual high school. Distance Education, 34(1), 64–83.

- Henson, A. R. (2014). The success of nontraditional college students in an IT world. Research in Higher Education Journal, 25. Retrieved from http://www.aabri.com/manuscripts/141911.pdf

- Herbert, M. (2006). Staying the course: A study in online student satisfaction and retention. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 9(4). Retrieved from http://www.westga.edu/~distance/ojdla/winter94/herbert94.htm

- Hew, K. F. (2015). Promoting engagement in online courses: What strategies can we learn from three highly rated MOOCs? British Journal of Educational Technology, 47(2), 320–341. doi:10.1111/bjet.12235

- Holder, B. (2007). An investigation of hope, academics, environment, and motivation as predictors of persistence in higher education online programs. Internet and Higher Education, 10(4), 245–260.

- Hoskins, S. L., & Newstead, S. E. (2009). Encouraging student motivation. In H. Fry, S. Ketteridge, & S. Marshall (Eds.), A handbook for teaching and learning in higher education: Enhancing academic practice (3rd ed., pp. 27–39). London, UK: Routledge.

- Hu, Y. (2008). Motivation, usability and their interrelationships in a self-paced online learning environment. (Order No. DP19570). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global (1030135967). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.library.ipfw.edu/docview/1030135967?accountid=11649

- Huett, J., Kalinowski, K., Moller, L., & Huett, K. (2008). Improving the motivation and retention of online students through the use of ARCS-based emails. American Journal of Distance Education, 22(3), 159–176.

- Huett, J. B., Young, J., Huett, K. C., Moller, L., & Bray, M. (2008). Supporting the distant student: The effect of ARCS-based strategies on confidence and performance. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 9(2), 113–126.

- Ilgaz, H., & Gülbahar, Y. (2015). A snapshot of online learners: E-readiness, e-satisfaction, and expectations. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 16(2), 171–187.

- Inkelaar, T., & Simpson, O. (2015). Challenging the “distance education deficit” through “motivational emails.” Open Learning, 30(2), 152–163.

- Intrinsic motivation doesn’t exist, researcher says. (2005, May 17). PhysOrg.com. Retrieved from http://www.physorg.com/news4126.html

- Ivankova, N. V., & Stick, S. L. (2005). Collegiality and community-building as a means for sustaining student persistence in the computer-mediated asynchronous learning environment. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 8(3). Retrieved from http://www.westga.edu/~distance/ojdla/fall83/ivankova83.htm

- Jackson, A. P., Smith, S. A., & Hill, C. L. (2003). Academic persistence among Native American college students. Journal of College Student Development, 44, 548–565.

- Kauffman, H. (2015). A review of predictive factors of student success in and satisfaction with online learning. Research in Learning Technology, 23. Retrieved from http://www.researchinlearningtechnology.net/index.php/rlt /article/view/26507

- Keller, J. M. (2000). How to integrate learner motivation planning into lesson planning: The ARCS model approach. Paper presented at VII Semanario, Santiago, Chile. Retrieved from http://apps.fischlerschool.nova.edu/toolbox /instructionalproducts/ITDE_8005/weeklys/2000-Keller-ARCSLessonPlanning.pdf

- Keller, J. M. (2008a). An integrative theory of motivation, volition, and performance. Technology, Instruction, Cognition and Learning, 6, 79–104. Retrieved from http://www.oldcitypublishing.com/FullText/TICLfulltext/TICL6.2fulltext /TICLv6n2p79–104Keller.pdf

- Keller, J. M. (2008b). First principles of motivation to learn and e-learning. Distance Education, 29(2), 175–185.

- Keller, J. M. (2010). Motivational design for learning and performance: The ARCS model approach. New York, NY: Springer Science and Business Media.

- Keller, J. M. (2011). Five fundamental requirements for motivation and volition in technology-assisted distributed learning environments. doi:10.5216/ia.v35i2.12668.

- Keller, J. M. (2016). ARCS design process. [website]. Retrieved from http://www.arcsmodel.com/?utm _campaign=elearningindustry.com&utm_medium=link&utm_source=%2Farcs-model-of-motivation

- Keller, J. M., & Suzuki, K. (2004). Learner motivation and e-learning design: A multinationally validated process. Journal of Educational Media, 29(3), 229–239. doi:10.1080/1358t65042000283084

- Kim, C., & Keller, J. M. (2007). Effects of motivational and volitional email messages (MVEM) with personal messages on undergraduate students’ motivation, study habits and achievement. British Journal of Educational Technology, 39(1), 36–51. doi:10.1111/j.1467–8535.2007.00701.x

- Koballa, T. R., & Glynn, S. M. (2007). Attitudinal and motivational constructs in science learning. In S. K. Abell & N. G. Lederman (Eds.), Handbook for research in science education (pp. 75–102). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Kohn, A. (1993). Punished by rewards. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

- Kuo, Y., Walter, A. E., Belland, B. R., & Schroder, K. E. (2013). A predictive study of student satisfaction in online education programs. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 14(1). Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/1338/2416

- Lee, Y., & Choi, J. (2011). A review of online course dropout research: implications for practice and future research. Educational Technology Research and Development, 59(5), 593–618. doi:10.1007/s11423–010–9177-y

- Levy, Y. (2003). A study of learners’ perceived value and satisfaction for implied effectiveness of online learning systems. (Doctoral dissertation). Arizona State University. Dissertation Abstracts International, 65(3), 1014A.

- Levy, Y. (2007). Comparing dropouts and persistence in e-learning courses. Computers and Education, 48(2), 185–204.

- Lewes, D., & Stiklus, B. (2007). Portrait of a student as a young wolf: Motivating undergraduates (3rd ed.). Pennsdale, PA: Folly Hill Press.

- Ley, K., & Gannon-Cook, R. (2014). Learner-valued interactions: Research into practice. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 15(1), 23–32. Retrieved from http://www.aect.org/pdf/proceedings13/2013/13_16.pdf

- Liaw, S-S. (2008). Investigating students’ perceived satisfaction, behavioral intention, and effectiveness of e-learning: A case study of the Blackboard system. Computers and Education, 51, 864–873.

- Liao, H., & Wang, Y. (2008). Applying the ARCS motivation model in technological and vocational education. Contemporary Issues in Education Research, 1(2), 53–58.

- Lidwell, W., Holden, K., & Butler, J. (2010). Universal principles of design. Beverly, MA: Rockport Publishers.

- Lin, Y., McKeachie, W. J., & Kim, Y. C. (2001). College student intrinsic and/or extrinsic motivation and learning. Learning and Individual Differences, 13(3), 251–258.

- Liu, J., & Tomasi, S. D. (2015). The effect of professor’s attractiveness on distance learning students. Journal of Educators Online, 12(2), 142–165.

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1990). A theory of goal setting and task performance. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Lysakowski, R. S., & Walberg, H. J. (1981). Classroom reinforcement and learning: A quantitative synthesis. Journal of Educational Research, 75(2), 69–77.

- Major, C. H. (2015). Teaching online: A guide to theory, research, and practice. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Marguerite, D. (2007). Improving learner motivation through enhanced instructional design. (Master’s thesis). Athabasca University Governing Council, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

- Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and personality. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

- Mayer, R. E. (2014). Incorporating motivation into multimedia learning. Learning and Instruction, 29, 171–173.

- McClelland, D. C., & Burnham, D. H. (1976). Power is the great motivator. Harvard Business Review, 54(2), 100.

- McGuire, S. Y., with McGuire, S. (2015). Teach students how to learn: Strategies you can incorporate into any course to improve student metacognition, study skills, and motivation. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

- Moore, J. (2014). Effects of online interaction and instructor presence on students’ satisfaction and success with online undergraduate public relations courses. Journalism and Mass Communication Educator, 69(3), 271–288.

- Müller, T. (2008). Persistence of women in online degree-completion programs. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 9(2), 1–18.

- Norman, D. A. (2005). Emotional design: Why we love (or hate) everyday things. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Nilson, L. B. (2013). Creating self-regulated learners: Strategies to strengthen students’ self-awareness and learning skills. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

- Nilson, L. B. (2016). Teaching at its best: A research-based resource for college instructors (4th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Noesgaard, S. S., & Ørngreen, R. (2015). The effectiveness of e-learning: An explorative and integrative review of the definitions, methodologies, and factors that promote e-learning effectiveness. Electronic Journal of E-Learning, 13(4), 278–290.

- Online Learning Insights. (2016, July 23). How and why to use social media to create meaningful learning assignments [web log]. Retrieved from https://onlinelearninginsights.wordpress.com/

- Park, J-H., & Choi, H. J. (2009). Factors influencing adult learners’ decision to drop out or persist in online learning. Educational Technology and Society, 12(4), 207–217.

- Pelz, B. (2004, June). (My) three principles of effective online pedagogy. Journal of Asynchronous Online Learning Networks, 8(3). Retrieved from https://www.ccri.edu/distancefaculty/pdfs/Online-Pedagogy-Pelz.pdf

- Rigby, C. S., Deci, E. L., Patrick, B. C., & Ryan, R. M. (1992). Beyond the intrinsic-extrinsic dichotomy: Self- determination in motivation and learning. Motivation and Emotion, 16(3), 165–185.

- Ripley, A. (2013). The smartest kids in the world and how they got that way. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

- Robb, C. (2010). The impact of motivational messages on student performance in community college online courses.(Order No. 3430898). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global (778224030). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/openview/5f95506841cb3ccf43d440986d2af02e/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

- Robb, C. A., & Sutton, J. (2014). The importance of social presence and motivation in distance learning. Journal of Technology, Management, and Applied Engineering, 31(2), 2–10.

- Rotter, J. B. (1975). Some problems and misconceptions related to the construct of internal versus external control of reinforcement. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 43, 56–67.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Class definition and new directions. Contemporary Education Psychology, 25(1), 54–67.

- Sankey, M. D. (2002). Considering visual literacy when designing instruction. e-Journal of Instructional Science and Technology, 5(2). Retrieved from http://ascilite.org/archived-journals/e-jist/docs/Vol5_No2/Sankey-final.pdf

- Schunk, D. H. (2012). Learning theories: An educational perspective (6th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

- Seligman, M.E.P. (1975). Helplessness: On depression, development, and death. New York, NY: Freeman.

- Shih, C., & Gamon, J. (2001). Web-based learning: Relationships among student motivation, attitude, learning styles, and achievement. Journal of Agricultural Education, 42(4), 12–20. (ERIC EJ638591.)

- Stöter, J., Bullen, M., Zawacki-Richter, & Prümmer, C. (2011). From the back door into the mainstream: The characteristics of lifelong learners. In O. Zawacki-Richter & T. Anderson (Eds.), Online distance education: Towards a research agenda (pp. 421–457). Edmonton, Alberta, Canada: Athabasca University Press.

- Sun, P., Tsai, R. J., Finger, G., Chen, Y., & Yeh, D. (2008). What drives a successful e-learning? An empirical investigation of the critical factors influencing learner satisfaction. Computers and Education, 50(4), 1183–1202.

- Svinicki, M. (2004). Learning and motivation in the postsecondary classroom. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass/Anker.

- Tomita, K. (2015). Principles and elements of visual design: A review of the literature on visual design studies of instructional materials. Educational Studies, 56, 165–173.

- Urdan, T. (2003). Intrinsic motivation, extrinsic rewards, and divergent views of reality. [Review of the book Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: The search for optimal motivation and performance]. Educational Psychology Review, 15(3), 311–325.

- Visser, L. (1998). The development of motivational communication in distance education support. Retrieved from http://www.learndev.org/People/LyaVisser/DevMotCommInDE.pdf

- Visser, L., Plomp, T., & Kuiper, W. (1999). Development research applied to improve motivation in distance education. In Annual Proceedings of Selected Research and Development Papers Presented at the National Convention of the Association for Educational Communications and Technology. Houston, TX. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED436169.pdf

- Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. (2000). Expectancy-value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 68–81.

- Willging, P. A., & Johnson, S. D. (2009). Factors that influence students’ decision to drop out of online courses. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 13(3), 115–127.

- Woodley, A., & Simpson, O. (2014). Student dropout: The elephant in the room. In O. Zawacki-Richter & T. Anderson (Eds.), Online distance education: Towards a research agenda (pp. 459–484). Edmonton, Alberta, Canada: Athabasca University Press.

- Zammit, J. B., Martindale, T., Meiners-Lovell, L., & Irwin, R. (2013). Strategies for increasing engagement and information seeking in a multi-section online course: Scaffolding student success through the ARCS-V model. In Proceedings of Selected Research and Development Papers Presented at the Annual Convention of the Association for Educational Communications and Technology, 1. Anaheim, CA. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED546877