![]()

CHAPTER SEVEN

DESIGN YOUR JOB TO FIND YOUR MEANING

Remember how I called my college cross-country coach, Coach Phemister, to help me deal with my boss, George, who called my husband to find out if I left work early because I was sick? As you may recall, this conversation inspired me to reframe my job selling booth space for a home and garden show as a place to develop and refine my sales skills. This worked for a while, and I was even promoted. However, the work continued to feel transactional and sterile. Something was still missing. Where was the value and meaning in my work? Was it even possible for a sales job to have a purpose beyond making money? And did it really matter if my job had meaning? What, if anything, would change for me if my job had significance beyond a paycheck?

On my way to work one cold, dark February morning, I heard an economics professor on National Public Radio say that all work had meaning. He said that all businesses create and provide products and services that provide real benefits; otherwise people would not buy them. I remember thinking that was a logical argument. The exposition company I worked for that produced home and garden shows could not have been in business for over 40 years if no one bought what it sold.

For the rest of the drive, I thought about Tammy, who sold “squirrel-proof” bird feeders. On the large TV in the center of her booth space she showed videos of squirrels trying, unsuccessfully, to fit their paws into the small crevices of her bird feeder. And I thought about Cheryl’s booth walls adorned with gorgeous pictures of backyard ponds filled with goldfish and water lilies and small waterfalls cascading over gray craggy rocks that she had installed in her customers’ yards. I thought about the benefits of the booth space I sold. However, as soon as I pulled into the company parking lot, thoughts of my mile-long to-do list jolted me from my existential reflection. It was back to the unfulfilling grind.

A few weeks later, as I reviewed my sales to date and my warm prospect list, I realized that more than 90 percent of my customers and prospects were small business owners in their first or second year of business who operated without a storefront. And most of them were women. I recognized, for the first time, the value I provided.

An inexpensive physical space with consistent, high-volume traffic enabled these new entrepreneurs to market, sell, and test their products and services. In that moment, I reframed and redefined how I thought about and experienced my work. I shifted from thinking about my work as a transactional telemarketer of 10×10 booth space to an enabler of small business growth and innovation. I helped and supported women, women like my Mom who also was a small business owner, achieve their business dreams. This was a purpose beyond my paycheck. I had defined the meaning in my work.

![]()

The value and importance of your work is defined by you. Meaning is not controlled by what happens in your life. It is made by your interpretation of the events in your life. Your inner self-talk shapes, constructs, and defines it. Since we all view the world through a different lens, it is impossible to provide a universal, one-size-fits-all definition of meaningful work. It is too subjective. Meaning is what you bring to the table. It is uniquely yours. No one can define it for you.

You can find meaning in any job because you define it. No jobs are exempt from significance. To identify the value in your work, think about the context of work in your life. For example, work is a paycheck, or it’s a higher calling, or it’s a form of creative expression. You can find worth in your work through your interactions with other people by being on a team united around a common purpose or expressing common values and beliefs. Substance can be found in the context or nature of the work, the tasks you perform, the organization’s mission or commitment to the environment, sustainability, or community service.

When you change how you frame your work’s purpose, you change the meaning of your work and transform how you define yourself as a doer of the work.1 Once I no longer saw myself as a transactional telemarketer, my work experience radically changed. To be an enabler of small business growth inspired, energized, and motivated me. My job was no longer a grind. When my alarm went off on Monday mornings, I did not hit snooze five times. I wanted to get out of bed and go to work. I needed to be at my desk because my work mattered to the small business owners I served.

You spend more than one-third of your waking life at work. Whether work has the starring role, is a small player, or is the hero or villain in your life completely depends on you and your relationship to your work. Now is the time for you to step powerfully and confidently into the deeper why of your work. The final step in your journey to own, love, and make your job work for you is to design your job to find your meaning.

IS YOUR WORK A JOB, A CAREER, OR A CALLING?

Almost once a week, for the past 10 years, I have taught a corporate training class. During this time, I’ve observed that there are three types of people who attend my workshops: prisoners, participants, and students.

The prisoners make it known that they are only in the workshop because it is a mandatory requirement. Prisoners do what is minimally required to receive “credit” for the class, while they check their smartphones and count down the minutes to the next break or the end of the day.

The participants are in the workshop because they need the knowledge, skills, or experience to advance their career. They often sit near their manager or a person with higher status or power to develop or strengthen a connection with them. Participants thoughtfully answer my questions and are careful to ensure that their workshop engagement elevates their brand and reputation.

The students are in the workshop because they want to grow. They want to learn a new skill and/or explore an alternative perspective, approach, or idea that may help them in their career.

A few months ago, after coaching three people who were the same age and gender and also held the same position and occupation, I recognized that people who do the same work can and do experience that work differently. Just as there are three different types of people and experiences in my training classes, people relate to their work in three distinct ways. Isn’t it liberating to realize that you have control over your experiences?

You have the power and can design your job to derive more significance from it. In order to make that happen for you, let’s start with an awareness of where you are right now. Why? Because all change starts with an awareness of your current connection to your work.

Read the paragraphs below and decide if any of them describe your current affiliation to work. You might read one paragraph and find that it explains exactly how you connect to your work. Or you might read them all and realize that you relate to your work as a combination of two or three. That is fine. Stay focused on the goal and identify how you relate to your work today.

If you connect to your work as a job, it is a necessity of life. It is how you pay the bills. Your job is how you support your life, hobbies, and interests outside of work.2 You do not seek or receive any other reward from it. You live for 5 p.m., the weekend, and your next vacation. And if you were asked if you would enter this profession again, or encourage your family or friends to enter this profession, you say no, probably “Hell no!”

If you relate to your work as a career, the focus is on achievement and advancement. For example, if you meet a person who relates to their work as a career at a networking event and ask them what they do, they might tell you what they do in the context of their accomplishments. “I lead Talent for my company and report to the board of directors on our progress. I also lead HR for our corporate office, and report to our general counsel (chief legal officer) but take most of my direction directly from our CEO. I am the most senior person in HR now, and really enjoy my role.” If your work is a career, you probably don’t expect to be in your current job in a few years because you plan to move on to a better, higher-level job. A promotion is a recognition that you have outperformed your coworkers.3

If you relate to your work as a calling, work is not for financial gain or career advancement. Work is a source of fulfillment. It is one of the most important parts of your life and a vital part of who you are. At parties your work is one of the first things you tell people about yourself. If you won the lottery today, you would still do your work. You probably dread the thought of retirement and have encouraged friends and family members to join this profession. You love your work and believe it makes the world a better place.4

It is probably not a surprise to you that people who relate to their work as a calling experience greater life, better health, and job satisfaction.5 You might be thinking that only people in “passion” professions can and do experience work as a calling. You must be an artist, writer, teacher, nurse, minister, etc., to relate to your work as a calling. I hear you. However, I have seen with our clients, in my own company, and with my colleagues and friends that this simply isn’t true. You can relate to your job as a calling regardless of occupation, age, income, and education.

You define how you experience your work. If you want your job to be more than a transactional necessity, it can be. If you want your career to have purpose beyond your next promotion, it can. If you want your calling to have deeper, richer meaning, it can. However, in order to make that happen, you have to acknowledge that you have the power to create a professional life that aligns with who you are and how you choose to make an impact in and for the world.

DESIGN YOUR WORK FOR MORE MEANING

Celia is the unit secretary in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit in one of the largest hospital systems in the country. She answers the phone, coordinates physician and therapeutic consultations, and ensures that deliveries go to the correct nurse, patient, or family member. The work she performs is transactional and administrative. However, that is not how Celia experiences her work.

“I am the Mother Hen of this floor. All the people I work with are my children. I care for them so they can care for our patients. I am the concierge for our patients’ families. If they need anything, I will get it for them. I also help care for our patients. I make sure that medications get to the nurses from our pharmacy system,” Celia told me when I interviewed her for this book.

Celia views her job as a valuable whole that positively impacts other people, not a collection of separate tasks. She proactively and intentionally designed her work to derive meaning from it. How? She modified and extended the scope and nature of a unit secretary’s responsibilities to support a broader purpose in her work. She even took on additional duties that align with how she experiences and relates to her work as the “Mother Hen” of the floor.

“I asked the medical director if I could be responsible for stocking the refrigerator and snacks in the breakroom. Food services doesn’t know what my nurses, physicians, and team members like and need. I do. I take care of them so they can take care of our patients. Twice a month, I do an inventory and ask the members of the team what they need or if they want anything special. I shop on my way home from work and bring the drinks and food in the next morning,” Celia said.

To do significant work requires that you take action to make your job requirements feed a broader purpose. You must be an active designer and creator of your professional experience. You can shape your vocation to fit your own unique orientation and bond with it. You have the power to structure your job differently to create value in your work.

It’s time for you to take the reins, and in order to do so, you must make behavioral, relational, and/or psychological changes to how you work and/or to how you relate to your work.

There are three areas where you can shape your work: task, relational, and cognitive,6 and each one involves specific types of modifications you can make to how you work.

• Task. You make behavioral changes to how you perform your set of assigned job activities. Either you adjust the scope or nature of assignments involved in your job, or you take on additional responsibilities.

• Relational. You make changes to your professional relationships. Either you alter the extent or nature of your affiliation with the people you currently work with, or you develop and build new associations.

• Cognitive. You make proactive psychological changes to your perceptions of your job. You redefine what you see as the type or nature of the duties or relationships involved in your job. And you reframe your job to see it as a meaningful whole that positively impacts others rather than a collection of separate responsibilities.7

So, what does it look like to make task, relational, and cognitive changes at work? Let’s dive deeper into each area to find out.

Task Changes

You have two options to adjust the tasks in your job.

The first option is to modify either their scope or their nature. For example, Ava is the project manager at a national construction supply company, and one of her responsibilities is to ensure that the construction team uses high-quality products on its projects. While researching innovative building supply materials, she would explore and brainstorm marketing opportunities for the company, which was not part of her job. However, because she was interested in it, she used this as an opportunity to modify the scope and nature of her job.

The second option to alter your tasks at work is to take on one or more additional responsibilities. For example, in her meetings with the sales team, the owner of the company, or the project site supervisors, Ava now shares a promotional idea for how to use the product selections to differentiate the company from its competition.

In Chapter Four you excavated your strengths and used them to shape your work to meet your personal and professional goals. Now go one step further and use your strengths to make your work have more value. Refer to your list of strengths from Chapter Four and answer the questions below for each strength:

1. What job duty could I modify so that I can more fully use my strengths to add more meaning to my job?

2. What strength am I not using that I want to use to unlock more significance in my work? What task could I add to use this strength and find more value in my work?

Review your answers to each question and find the job responsibility that you can modify without the approval of your manager. Then, just do it! How good does that feel? For other assignments that need input from your manager, schedule a meeting to discuss what you want to do and how it will benefit both you and the company.

Relational Changes

Now let’s explore how you can alter your professional relationships.

Your first option is to change the extent or nature of an existing relationship. For example, Joe, an associate at an insurance company, adjusted his relationship with his manager, Susan. “I’ve limited some of my interactions with Susan because she will spend hours in meetings going over and over quote details. For example, we’ve had meetings that last two or three hours on a quote that we could have discussed in just one hour. So now, if there is a meeting scheduled to review a quote, I know I should schedule another meeting to start one hour after my meeting with Susan. This ensures that our meeting ends on time and that the quote review is complete. This has saved me hours, and I don’t think Susan has really noticed because all my quotes have been completed correctly and submitted on time.”

You can also develop new connections to derive more meaning from your work. For example, Jill is the second highest ranking woman in a global manufacturing firm. She has achieved extraordinary success and is three years away from retirement. At our last executive coaching session, she said to me, “We have been discussing my career, my legacy, and the imprint I want to leave on this company. I decided I want to support, develop, and advocate for women. Of course, it is outside of my day-to-day responsibilities; however, this is important, significant work to me. Once I made this decision, I met with Nicole, who leads our Women’s Connect group, and now I am helping her plan the group’s upcoming networking event in March. I also worked with my HR generalist and identified the top 15 high-potential women in my business. Now, when I am in a city where one of them works, I take them out to lunch or to dinner to get to know them better and learn how I can help them advance in their careers. I’ve never felt more engaged and alive!”

Now, it’s your turn to brainstorm how you might modify a professional relationship.

1. Identify the five to seven people with whom you interact the most frequently in your job. You want to focus on these people, because if you change one of these relationships, it can make a significant, positive impact on your experience at work. This could be your manager, your coworker who sits next to you, or a person from a different department who is on a project team with you.

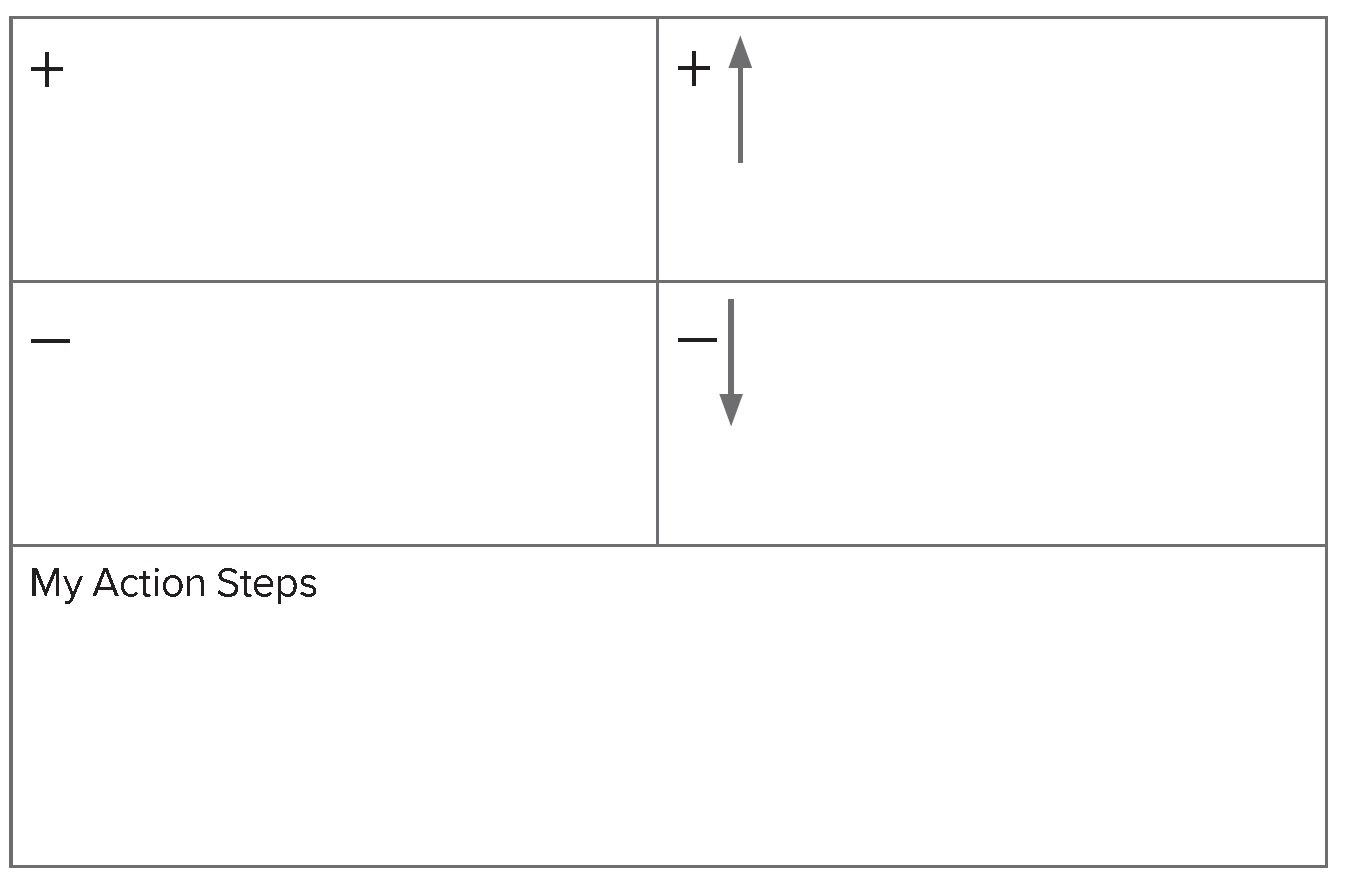

2. At the top of a sheet of paper, write the name of one of the people you’ve just identified. Draw two lines horizontally to divide the paper into thirds. Then draw a line to divide the paper vertically, stopping at the second horizonal line on the paper. Do not draw a line through the second horizontal line. You now have four square quadrants and a rectangle below them. In the upper-left quadrant, draw a plus sign (+). In the upper-right quadrant, draw a plus sign and an up arrow. In the lower-left quadrant, draw a minus sign (–). In the lower-right quadrant, draw a minus sign and a down arrow. You can see an example of what your page should look like in the figure.

Sally Wells, Manager

3. The upper-left quadrant represents the positive aspects of your relationship with this person. In this box list all the positive benefits and value you encounter when you interact with this person.

4. The upper-right quadrant represents the positive aspects of your relationship that you want to experience more often. In this box list what you want more of in this relationship.

5. The lower-left quadrant represents the negative aspects of the affiliation with this person. In this box list the negative interactions that have undermined your fulfillment and joy at work. You might not have any undesirable experiences with this person. If so, skip this box.

6. The lower-right quadrant represents the unconstructive aspects of the relationship you want to have less often. In this box list what you want less of in your interactions with this person. This can be something you want to stop completely, or just minimize.

7. Now, in the horizontal box at the bottom of the page, write down two action steps you will take to change your rapport with this person. I suggest that one action step enable what you want more of in this relationship and the other action step support what you want less of. For example, remember how Joe limited his interactions with Susan? He intentionally scheduled a meeting to start one hour after the start time of his meetings with Susan. This was a small, simple modification. Don’t underestimate the power of incremental adjustments. Small changes quickly add up. They can fundamentally shift relationships without radical, jarring change, which makes them feel and be less risky. An example of the completed exercise is below.

8. Complete the steps above for each person you identified to modify your current relationship.

Sally Wells, Manager

You now have a road map to modify a professional relationship.

The second option to alter your professional relationships is to develop new professional connections. Your first step is to identify a passion you want to pursue, a special interest you have, an experience you want to have, or a new skill you want to develop that will help you derive more significance from your work. Then find the person or people who can help you. You may have to do some research on the company’s intranet site, talk to a coworker, or search LinkedIn to identify the right person. Once you know who can help you, reach out to that person and ask for the person’s support.

Now, it might seem awkward, politically risky, or just extremely uncomfortable to reach out to people you don’t know or who are in a more senior position than you. I get it. However, when our clients reach out to people they don’t know in their company, they consistently receive enthusiastic support and encouragement. Still on the fence? Think about it this way. If you reach out to people because of a passion and interest to join, support, or advocate on behalf of a project or a cause, why would they turn you away? They need and want your participation. Your interest in their project or cause also validates its importance. When you reach out to others to learn more about their work, skills, or career, you reinforce their worth and contributions to the company.

Cognitive Changes

The final place you can design your work is cognitively, which is how you define and relate to your work. When you do this, you reframe your job to see it as an important whole that positively impacts others rather than a collection of separate to-dos.

How? Expand the lens through which you observe your work. You want to zoom out so you can look at your responsibilities as a collection of tasks, not a set of individual duties. Don’t focus on just one aspect of your work, and don’t look at a single to-do task in isolation. Each task is part of a greater whole. It is the composite of them all that has the value and purpose for you.

To see the collective whole of your work, list all your job accountabilities. For each one, ask yourself the question, “So what?” This question acts as a way for you to identify the importance or significance of each duty. For example, when I sold booth space at home and garden shows, my job description stated “Make a minimum of 50 outbound sales calls a week.” So what? My answer to that was “To market our trade show to as many business owners as possible and to introduce business owners to trade shows as an option to sell their products and services.” That’s a lot more inspiring than “Make 50 outbound sales calls.”

After you have answered the “So what?” question for each of your tasks, look at your answers. Is there a theme or a common link among them all? Is there a primary objective or goal of your work? In my work, the objective or goal was to produce a trade show where business owners could sell their products and services to a targeted group of people who had an interest in and/or need for them. How would you describe the central objective of your work?

With this information in mind, you are now ready to uncover the meaning in your work and identify how your work positively impacts other people. Below are a few questions to consider. You might want to write down your answers or think about them and then discuss them with a friend, a coworker, or your spouse or partner.

• Why do people buy your product or service?

• What is the benefit your customers receive from using your product or service?

• What would happen if your product or service did not exist? For your customer? For your community?

• “How do you positively affect people?

Your final step is to write a meaning statement for your work. For example, the meaning statement in my sales job was “I help small business owners achieve their business dreams.” I encourage you to write your meaning statement down and post it where you can see it. Why? Because we all have bad days. There will still be something you don’t like. Your manager may “check in” on you for the third time in an hour, or the scent of your cubemate’s lunch may still permeate the cubicle you share the next day. Or you may still have to complete the long, detailed report no one reads. It is in these moments that a visual reminder of why you and your work matter is important.

When I was still working for George selling booth space for home and garden shows, I found myself in a two-month stretch where people hung up on me almost every other cold sales call, I actively disliked what was on my to-do list, and George was being even more of a micromanager jerk. I had reached my limit, so I wrote my meaning statement on a Post-it Note and taped it to my computer. I realized that when I disconnected from the meaning of my work or let it slip to the back of my mind, this note helped me avoid the dreaded “Take this job and shove it” spiral.

Maybe this sounds a little woo-woo or touchy-feely. Or it appears too simple. Just use a mental trick, and poof, your work has significance and is no longer a slog. I get it. However, your mind is incredibly powerful. Your thoughts impact how you experience your work. You can choose to experience your work positively or negatively because your beliefs and feelings are uniquely yours. No one can take them away from you, and no one can force or dictate what you must think and feel. This is your power. You can decide to perceive and experience your work as a source of meaning.

Task, relational, and cognitive changes are all interrelated and can influence each other. For example, Celia, the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit secretary, shaped both the cognitive and task aspects of her work. She thought of herself as the “Mother Hen” of the unit and took on the additional task of purchasing drinks and snacks for the unit breakroom to support her perception of her job.

YOU TRIED TO DESIGN YOUR JOB AND HIT A ROADBLOCK—NOW WHAT?

You took a powerful step forward to experience your work as meaningful. Then you hit a roadblock. Maybe you don’t have the formal power to design your job, or your supervisor put a pin in your efforts. Maybe you do have the autonomy to make these shifts, but your own expectations of how you use your time hold you back. Or maybe you are constrained because you don’t want to encroach on other team members. So, what can you do? Focus on the aspects of your work where you do have efficacy and control. Then be creative and adaptive.

If your position in the company affords you autonomy and formal power, this means you have influence over others. It also means you are likely responsible for the roadblocks you may experience. The first step is to own your power and responsibility. Then change your own expectations and behaviors.

For example, a director at a nonprofit, Daksh, wanted to do more student outreach, but he did not have the time to take on any additional projects. As he thought about his work, he realized while he might not be able to control all aspects of his job, he does have the power to define and guide the strategic direction of the organization. Daksh could reprioritize his team’s focus areas so he and his team could spend more time on student outreach. He also recognized that everything he does each day is because he chooses to do it. The amount of time he spends on certain tasks and the prioritization of his work is decided by him. If you think about your work this way, it can help you be content with the time constraints that limit your ability to design your work and help you overcome feeling limited by your own beliefs of how you should spend your time and energy at work.

If you have limited time to design your job during your work hours, you can use your time outside of the workday. Which is what Jill did when she decided to volunteer with the Women’s Connect committee in order to support, develop, and advocate for women. She is on the committee and participates in events that typically occur outside of her normal business day, either early in the morning or in the evening. There is one networking event a month and two quarterly two-day events a year. The time commitment is appropriate for her current schedule. Any more time would be prohibitive.

Now, what can you do if you work in a job where you are required to complete an assigned set of duties in a prescribed way? Maybe you are a database manager, or work in a customer call center, or do data entry. Your challenge is that you do not have the autonomy and formal power to design your job. So you focus your efforts outward. You adapt by changing others’ expectations and behaviors so you can design your work. There are three ways you can do this: leverage your strengths to create opportunities, identify and reach out to people who can help you create opportunities to design your work , and/or build trust with people to create an opening to design your work.

Leverage your strengths to create opportunities. You identified your strengths in Chapter Four in order to support the accomplishment of your company’s goals. This gave you the autonomy to shape your work in a way that met both your professional and personal needs and goals. Now you can use those same strengths to provide value to your coworkers to change their opinion of you so you can create opportunities to design your work. For example, Avery, a customer service representative at a telecommunications company, studied information systems in college. She has a computer background and enjoys technology. There were technical elements of the customer service representative job that required the support of the IT department. Avery identified what she could do herself instead of the IT department and has become the go-to person to solve minor IT issues on the team. Avery proactively added tasks she enjoys, and is good at, to her job.

Reach out to people who can help. Another strategy you can use to change others’ expectations and behaviors so you can shape your work is to identify and reach out to people who can help you create opportunities to design your work. For example, Henry, a maintenance technician at a manufacturing company, wanted to improve procedures to reduce bottle cap production time. He identified a coworker in the engineering department, Jose, who could train him on the machines in the plant. Henry asked Jose about the mechanical aspects of the machines and shared with him what he observed worked and did not work on the plant floor. As a result of his association with Jose and the training he received, Henry modified the bottle cap application process and reduced production time by two minutes. He proactively added value to the company and shaped his job for more gratification.

Build trust to create an opportunity. An additional approach you can use to change others’ expectations and behaviors so you can design your work is to build trust with people to create an opening to design your work. This option will take more time, energy, and patience; however, it is very effective. For example, when Kiaan started his job at a university in the fundraising department, his job involved data entry, systems management, record keeping, email correspondence, and scheduling meetings. Kiaan wanted to help prospect and cultivate donors. He did not want to attend meetings and only take notes. Kiaan began to anticipate his manager’s needs and build rapport with current donors, and demonstrated through his high-quality work that he could take on additional responsibility. His manager began to trust him and see that he was able to develop relationships and that his peers and other people in the organization trusted him. As a result, Kiaan spends most of his time now on donor cultivation, prospecting, and stewardship. He is more content and invested in his work.

Do not allow yourself to hold you back. Focus your time and energy where you do have control and efficiency. Then get creative and adapt. You can design your job and have more satisfaction, joy, and success.

YOU HAD A CONVERSATION AND NOTHING HAPPENED—NOW WHAT?

Tuesday afternoon you met with your boss and discussed modifications to two of your job responsibilities. Thursday you had coffee with a team member and asked to volunteer at the after-school girls’ coding program she started three months ago. Empowered and energized, you looked forward to Monday morning. That was six weeks ago. Sound familiar?

Frustrated, disappointed, angry, or perhaps nervous that you may have damaged your career, you create a story about your boss’s and team member’s silence and inaction. They got busy and forgot about the conversation. It’s bad news so they are avoiding the conversation. They don’t like change and the status quo works fine for them. It’s a political quagmire that requires extra energy, time, documentation, and/or political capital. They are lazy and do not want to go to the effort to advocate on your behalf. It could be any, all, or a combination of these reasons. The problem is that you don’t know. You are caught in a vicious and unproductive cycle of conjecture, fabrication, and fantasy.

To get what you asked for, you must know the specific cause of the unresponsiveness. And the only way to find out is to have a follow-up conversation. Before you schedule the conversation, you need to be clear on why your request matters to you.

• What was the catalyst for your ask? What’s at stake if you don’t receive what you asked for?

• How will what you asked for constructively impact you, your career, your team, and the company?

• What is the feeling that drove your ask?

• “What do you really want?

I want to give you examples to help you brainstorm your answers to these questions. However, sometimes my clients get stuck on my suggestions or ideas and think that these are the only way to solve a challenge. Then they try to fit their life and their unique situation to my example. So I am not going to give you examples. I don’t want you to take other people’s stories and make them fit your situation. Why? Because this is personal. You are on Chapter Seven. If you have been doing the exercises and reflection activities in this book, you’ve got this. I know you can do it. I am cheering you on.

Invest the time to answer each question. Your answers help you move through any residual negativity, anger, or frustration back to the confident, positive, empowered person who asked for what you needed and wanted. Now you are ready to have the follow-up conversation.

The follow-up conversation will include three parts: state the facts of the situation, share your story about the facts, and ask for your manager’s perspective.

Start the Conversation with the Facts

You start the conversation with the facts, because if you begin by sharing your feelings or stories, the other person may not understand what you’re talking about or may become defensive or angry and withdraw from the conversation. For example, if you tell a friend that she can’t be trusted (your story) and offer no further explanation, she isn’t sure why you drew this undesirable conclusion. Then, since she’s been accused of being untrustworthy, she will become defensive and get angry. The original facts may never even make it into the conversation.

Feelings and stories often keep you from the facts. Facts clarify the topic of conversation, and they are more persuasive and less controversial than stories. When you need to have a difficult conversation or share something that the other person might resist, it is more effective to share the facts behind the story before you share your story.

However, when we are emotionally charged, it can be easy to confuse facts with stories. A fact is an actual occurrence. It is something that can be proved through observation or measurement. Facts are what you saw and heard. For example, you met with Selena, your manager, on Tuesday, June 2. It is now Tuesday, July 7, five weeks since your conversation. You have not received an email or a phone call or had the in-person conversation you were promised about the two modifications to your job responsibilities. Based on these facts you would begin the conversation, “Selena, we met on Tuesday, June 2, and I asked you to modify two of my job responsibilities. It has been five weeks since that meeting, and I have not received any additional information or communication from you.”

Here are a few additional phrases you can use to make your points.

• “I saw . . .”

• “I noticed that . . .”

• “The last three times we talked about this . . .”

• “I was expecting you to be here at 7:00 a.m., and it’s now 7:30 a.m. . . .”

Sometimes the stories we tell ourselves about our boss’s inaction hinder our progress. Again, a story is a judgment, conclusion, or attribution you make from the facts. A judgment is used to determine whether facts are good or bad. You draw conclusions to fit elements of your story together. And you use attributions to explain why people do what they do. For example, you conclude that you have not heard from your boss Selena because she is lazy. She does not want to spend the time or the effort to advocate on your behalf. The problem with our stories is that they can be insulting or harsh or can include unattractive assumptions about another person’s behavior. If you shared these suppositions with other person, it’s only natural that the person would feel hurt or insulted. In contrast, when you share only what you’ve seen and heard, others are less likely to be offended. Start your conversation with the facts.

Share Your Story About the Facts

Of course, facts by themselves don’t always show the whole picture, which is why the second part of the conversation is where you share your story about the facts. Your story addresses why the facts matter to you. It describes your experience of the facts. When you share your story, it is imperative that you carefully choose your words and phrases. Avoid absolutes such as “must,” “have to,” or “the fact of the matter is . . .” You do not want to jeopardize the goal of the conversation, which is to understand the reason why no action was taken on your request.

Use one of the phrases below to avoid triggering an angry or defensive response:

• “I’m starting to think . . . ”

• “The story I’m telling myself is . . .”8

• “It seems to me that . . . ”

• “I’m wondering if . . . ”

For example, “I’m starting to think that it requires a lot of your time and energy to navigate human resources and the politics of modifying two of my job responsibilities.”

Sometimes when I do this exercise with my clients, they are concerned they will do all the talking and the conversation will last too long. Don’t worry. This is a quick process. It takes approximately three to four minutes to state the facts and share your story. These are succinct statements that establish the context of the conversation.

Use an open-ended question or one of the following questions:

• “What am I missing?”

• “Can you help me better understand what happened?”

• “How do you see it?”

• “What’s your perspective?”

Invite Your Manager’s Perspective

Now you are ready for the final step in the process, to invite your manager into the conversation and ask for their perspective. Once you’ve delivered the facts and your story, pause and listen carefully to your manager’s response. When you know the specific reason why no action has been taken on your request, you can look for and find a mutually beneficial solution with your manager.

However, what do you do if your manager does not offer their perspective or provide any additional information? What if they become angry or withdraw from the conversation? When someone has a reaction like this, it’s not because of what you are saying; it’s because of why they think you’re having the conversation.9 If they think your purpose is to blame, shame, or win, then they are going to either get angry or withdraw and avoid any additional interaction with you. For example, if Selena assumes the intent of your conversation is to tell her that you believe she is a lazy, ineffective, self-centered manager who does not care about you or your professional fulfillment, she will feel threatened and inadequate and exit the conversation.

If a conversation moves in this direction, restart it by first clarifying any misunderstandings that may have led your manager to confuse why you are having this conversation. When your manager knows that your intent is positive, they don’t worry that you are trying to force a solution, and they will be more willing to listen and hear your potentially negative or painful content. Explain your intent. Use a phrase that begins with “What,” such as “What I was trying to say” or “What I meant was.” Or “Selena, what I was trying to say is that working with human resources right now to approve modifying my job responsibilities is probably a challenge because of the time and energy required to launch our new product. I know you are committed to both me and the success of our new product.”

Once your manager realizes the conversation is not a personal attack and your intent is positive, the next step is to establish a shared goal that benefits both of you. You might say to Selena, “Let’s look at what is preventing us from moving forward and brainstorm ideas that will work for both of us.” Be open, receptive, and creative. And if you and your manager have different goals, think about how you can combine them so that you both get what you want and need. For example, if Selena needs to focus her time on the new product launch and you want to modify your job responsibilities, you could offer to meet with human resources and collect the required documentation and then help Selena complete the process. In this instance you both get what you want and need.

It may make you feel frustrated, demoralized, or upset to ask for what you want and need and be met with silence and inaction. When this occurs, don’t languish in silence and wish, hope, or pray for something to change. You are not helpless. Step up again and ask for a follow-up conversation. Uncover the reason for the inaction, and then work together to find a mutually beneficial resolution.

Remember, the meaning, value, and purpose of work is defined by you. It is uniquely yours. You can design your work to derive more value and fulfillment when you modify the task, relational, and cognitive aspects of your job. And when you hit a roadblock, you have the power to step up and have a conversation to uncover what is actually standing between you and your professional dreams.

You did it! You have turned your job into your dream job. Congratulations!

Now, it’s time for us to celebrate you and your new life.