CHAPTER 2

The Five Immutable Principles of Project Success

Project failure starts when we can’t tell what “done” looks like in any meaningful way. Without some agreement on our vision of “done”, we’ll never recognize it when it arrives, except when we’ve run out of time or money or both.

We’ve all seen the project failure numbers before.1 We’ve all been told how bad things are. We’ve all heard that large numbers of projects fail because of poor planning or poor project management. Whether this is true or not, how can we increase the probability of our own project’s success?

First, we must recognize that without a clear and concise description of done, the only measures of progress are the passage of time, consumption of resources, and production of technical features. These measures of progress fail to describe what business capabilities our project needs to produce or what mission we are trying to accomplish. In Chapter 1, we examined the ten drivers of project success, the first of which is that capabilities drive requirements. Therefore, without first identifying the needed capabilities, we cannot deliver a successful project, and we will end up a statistic like all the other failed projects.

With capabilities as our starting point, we’re now going to look at the Five Immutable Principles of project success as they apply to any project, in any domain, using any project management method and any project management tool.

As we’ve seen, the Five Immutable Principles are best stated in the form of five questions. When we have the answers to these questions, we will have insight into the activities required for the project to succeed in ways not found using the traditional process group’s checklist, knowledge areas, or canned project templates.

Before proceeding to the principles, let’s remind ourselves of the attributes of projects. First, projects are one-off events. Projects are not operations. They are not repeatable processes—although the processes that manage projects are repeatable. A project is a one-time occurrence. This is important because projects are a “one chance to get it right” type of endeavor. Operations have several chances to get it right—maybe a lot of chances, sometimes only a few, but never just one. To increase a project’s chances of success, the ten drivers, Five Immutable Principles, and Five Practices must all be followed.

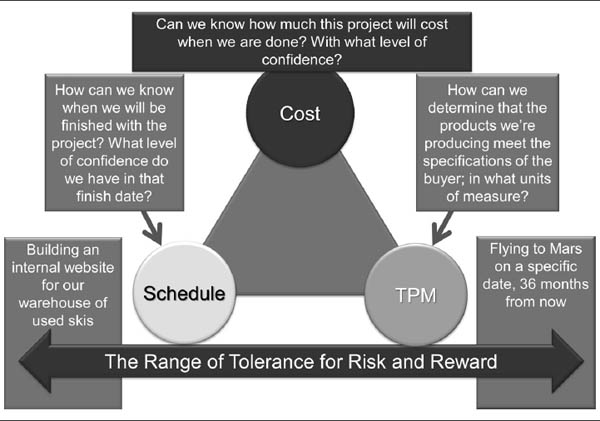

Second, projects have many variables: some dependent, some independent, some we can control, and some we can’t control. Three fundamental variables found in all projects are shown in Figure 2.1. These three variables interact in ways that are not easily discernible; however, we can ask three questions about them:

1. When will we be done?

2. How much will the project cost when it is done?

3. Will the deliverables from the project work when they arrive?

FIGURE 2.1 The three fundamental variables of projects.

A word used in all project work is probability. Projects have statistical behaviors that drive how likely it is that they will succeed. There is no guarantee of success, of course. All projects’ variables (cost, schedule, and technical performance) have associated uncertainties. As project managers, we’d like the probability of success to be as high as possible, and for some projects the probability of success is high—close to 100 percent. For some projects the probability of success, while acceptable, is actually low. The Five Immutable Principles focus on improving the Probability of Project Success (PoPS). The tradeoffs between risk and reward along the bottom of Figure 2.1 can now be seen in units of measure of cost, schedule, and technical performance. Risk becomes the common element between these three variables.

Another attribute common to all projects was suggested by Mr. Blaise Durante, Deputy Assistant Secretary (Acquisition and Integration) U.S. Air Force: There are only two phases of any project . . . (1) Too early to tell, and (2) Too late to stop.2

All project managers want to have other choices. To do so, we need to answer the three questions in ways that provide actionable information to the decision makers, both project management and stakeholders. The Five Immutable Principles help us do that.

Implementing the Five Immutable Principles

The Five Immutable Principles of project success are short and sweet. They are obvious, they are simple, and they are easily recognized. At the same time, they are hard to implement if we don’t consciously and intentionally take the time and effort to do so.

1. What does “done” look like? We need to know where we are going by defining “done” for some point in the future. This may be far in the future—months or years—or closer—days or weeks from now.

2. How can we get to “done” on time and on budget and achieve acceptable outcomes? We need a plan to get to where we are going, to reach done. This plan can be simple or complex. The fidelity of the plan depends on our tolerance for risk. The complexity of the plan has to match the complexity of the project.

3. Do we have enough of the right resources to successfully complete the project? We have to understand what resources are needed to execute the plan. We need to know how much time and money are required to reach the destination. This can be fixed or it can be variable. If money is limited, the project may be possible if more time is available and vice versa. What technologies are needed? What information must be discovered that we don’t know now?

4. What impediments will we encounter along the way and what work is needed to remove them? We need a means of removing, avoiding, handling, or ignoring these impediments. Most important, we need to ask and answer the question, “How long are we willing to wait before we find out we are late?”

5. How can we measure our progress to plan? We need to measure planned progress, not just progress. Progress to plan is best measured in units of physical percent complete, which provides tangible evidence not just opinion. This evidence must be in “usable” outcomes that the buyer recognizes as the things they requested from the project.

When we hear the word principles, we might think about the principles of playing baseball.3 Or the principles of garden design.4 Principles are guidelines and must be put into practice with some reasonable hope of success. The principles must be based on practices that have been shown to work in the domain in which they are being applied. The Five Immutable Principles can be applied in all domains, where projects are the means of producing results. In Chapter 5, there are examples of practices—based on these principles—applied to actual projects in a variety of domains.

The Role of Risk in Project Management

This is an idea that is not considered enough when we think about processes and principles. The amount of risk a project can tolerate is directly related to the business domain and the context of the project within that domain. Understanding the tolerance for these risk levels is critical, for example, to choosing and applying any software development method. The risk tolerance for schedule slippage is defined as the ability to still produce value for the customer in the presence of a late or slipping schedule; the Boeing 787 Dreamliner is but one example. The risk tolerance for cost means the customer can handle an overrun and still consider the project a success; the Sydney Opera House is a case in point. The risk tolerance for technical performance shortfall means the customer is willing to accept technical capabilities that are less than planned—the original Windows 7 release exemplifies this. With this risk informed background, we can look at the Five Immutable Principles.

What “Done” Looks Like

Let’s answer the first question from the point of view of the customer or the recipient of the outcomes of the project. For our purposes, the units of measure used to answer this question are the capabilities needed to meet the business mission goals. To reach “done,” we need a plan and a schedule.

Our first step is to separate the plan from the schedule. The plan is a procedure used to achieve an objective. It is a set of intended actions through which one expects to achieve a goal. The schedule is the sequence of the intended actions needed to implement the plan.

The plan is a strategy for the successful completion of the project. In the strategic planning domain, a plan is a hypothesis that needs to be tested along the way to confirm we’re headed in the right direction and will reach our goal.

The schedule is the order of the work that is needed to execute the plan. In project management, we need both. Plans without schedules are not executable. Schedules without plans lack a stated mission, vision, or description of success. All it says is that the work will be done.

Customers Buy Capabilities

Customers don’t buy development methods. They don’t buy requirements documents. They buy the plan because the answer to knowing what “done” looks like is described in the plan, and the customer is interested only in the final product. For that reason, the plan needs to answer the following questions:

![]() What capabilities are we seeking to deliver?

What capabilities are we seeking to deliver?

![]() What will the end user do with these capabilities that will create value for the business or fulfill a mission?

What will the end user do with these capabilities that will create value for the business or fulfill a mission?

![]() What are the Measures of Effectiveness of these capabilities in units meaningful to the decision makers?5

What are the Measures of Effectiveness of these capabilities in units meaningful to the decision makers?5

![]() What is the sequence for the delivery of each capability and what are the incremental increases in the maturity of each capability needed to deliver value to the customer?

What is the sequence for the delivery of each capability and what are the incremental increases in the maturity of each capability needed to deliver value to the customer?

When we ask, “What does ‘done’look like?” we should be referring to physical outcomes—the deliverables. By deliverables, we mean those things that enable the capabilities that fulfill the customer’s requirements.

Frederick P. Brooks Jr. in his 1987 essay “No Silver Bullet: Essence and Accident in Software Engineering,” said, “The hardest single part of building a system is deciding precisely what to build.”6

No matter what method we use to decide what to build—from the agilest of methods to the most formal—the requirements need to be stated in a form that is testable, verifiable, and traceable to the plan and schedule and the needed capabilities.

Capabilities Produce Measurable Value

“Done” is defined by the Measures of Effectiveness—the operational measures of success that are closely related to the achievements of the mission or its operational objectives evaluated in the operational environment, under a specific set of conditions as determined by the buyer. They answer these questions:

![]() Does the outcome of the project meet the needs of the customer?

Does the outcome of the project meet the needs of the customer?

![]() What capability does the customer now have that wasn’t there before?

What capability does the customer now have that wasn’t there before?

![]() Does this new capability provide measurable value?

Does this new capability provide measurable value?

![]() If so, what is the evidence that this value was derived from the delivered products or services?

If so, what is the evidence that this value was derived from the delivered products or services?

To be effective, a solution must address the user’s Critical Operational Issues (COI), which are associated with “mission success.” The COIs are the emergent properties of the solution that must be delivered to the customer for it to serve its function. If the solution does not have these characteristics, then it has not addressed the user’s needs and is therefore unacceptable. COIs are “show stoppers” in the real sense of the term, as they are the emergent properties that a solution to a need must possess in order to meet the need.

The Plan Shows the Capabilities’ Increasing Maturity

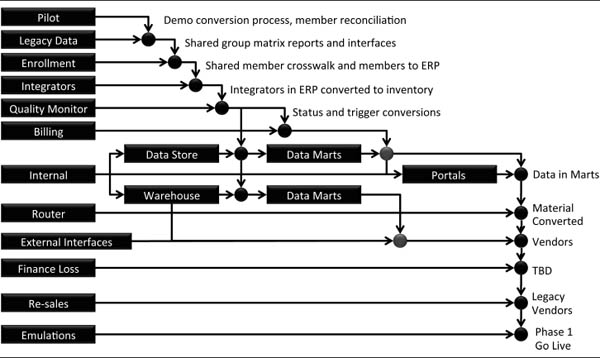

Figure 2.2 is an actual project’s master plan. This plan is for a healthcare insurance firm that is deploying a new provider network system. It begins with the development of a pilot system that integrates some test data and demonstrates that the conversion process for member reconciliation can be done as planned.

![]() This plan includes several concepts not usually found in a traditional project management approach, the first of which is that it starts with the requirements. A master plan is developed up front to provide the needed business capabilities before moving on to anything else in the project. In this case, it allows us to confirm that the pilot system can convert the data contained in the previous application to the new system.

This plan includes several concepts not usually found in a traditional project management approach, the first of which is that it starts with the requirements. A master plan is developed up front to provide the needed business capabilities before moving on to anything else in the project. In this case, it allows us to confirm that the pilot system can convert the data contained in the previous application to the new system.

![]() This work verifies the increasing “maturity” of the project’s deliverables; that is, the technical requirements are present, and we have a capability, possibly a small capability—that we can perform the conversion—which moves the maturity of the project one step higher.

This work verifies the increasing “maturity” of the project’s deliverables; that is, the technical requirements are present, and we have a capability, possibly a small capability—that we can perform the conversion—which moves the maturity of the project one step higher.

![]() The master plan contains all the steps needed to increase the maturity of the project as defined at the project’s outset. This does not mean we know all the details of “how” we are going to get to “done,” but it does show what “done” looks like at the end of the project. In Figure 2.2, this is labeled Phase 1 Go Live.

The master plan contains all the steps needed to increase the maturity of the project as defined at the project’s outset. This does not mean we know all the details of “how” we are going to get to “done,” but it does show what “done” looks like at the end of the project. In Figure 2.2, this is labeled Phase 1 Go Live.

The next step in the master plan after Phase 1, Go Live, is to integrate the enrollment subsystem. With this capability, using the pilot system and the legacy data, new providers can be enrolled. Add the integrators, the quality monitor, and the billing components and the first set of capabilities can be put to work.

Some might say this is just like Agile. That’s true, but the plan doesn’t say anything about developing software, features, stories, a schedule, or anything about developing products. It states in clear and concise terms what capabilities are needed in what order, and what the dependencies are among those capabilities. Notice the focus on “capabilities.” It’s the capability that the customer bought, not the development method, the code, or even the processes wrapped around most software or product development methods. These are all necessary but far from sufficient for project success.

FIGURE 2.2 This master plan lays out needed business capabilities for an insurance provider network system.

![]() Customers buy capabilities. These capabilities are implemented by products or services, but it is the capabilities that deliver the business value.

Customers buy capabilities. These capabilities are implemented by products or services, but it is the capabilities that deliver the business value.

![]() To find out what capabilities are needed, an elicitation process must be conducted before anything else is done on the project. Without knowing what capabilities are needed, we cannot know what “done” looks like.

To find out what capabilities are needed, an elicitation process must be conducted before anything else is done on the project. Without knowing what capabilities are needed, we cannot know what “done” looks like.

![]() For each capability, we need a Measure of Effectiveness. We’ll get to the details of MoEs in Chapter 3, but, for now, the MoE is the tangible evidence that the project is delivering the business or mission value the customer needs to call the project a success.

For each capability, we need a Measure of Effectiveness. We’ll get to the details of MoEs in Chapter 3, but, for now, the MoE is the tangible evidence that the project is delivering the business or mission value the customer needs to call the project a success.

How to Get to “Done” on Time and on Budget with Acceptable Outcomes

Once we know what capabilities need to be provided to the customer, in what order these capabilities are provided, and what the dependencies are among the capabilities, we will know what “done” looks like, as shown in Figure 2.2.

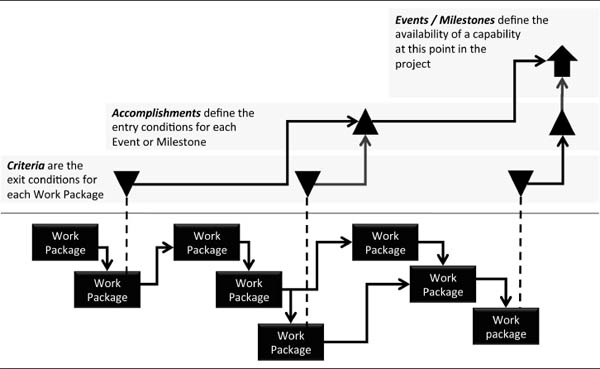

Figure 2.3 will be referred to in the following chapters. Along with Figure 2.2, it is the basis for managing any project. Together they describe two critical processes needed for any project’s success. Each planned capability in Figure 2.2 can be represented as a milestone or event in Figure 2.3. The integration of the enrollment processes with the Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) system can be a milestone. So can the conversion of all the legacy materials. We can define any usable deliverable as a milestone. The milestone or event represents the ability to do something useful with the deliverables of the project. The best useful thing is to put them to work. Process orders, make a product, fly to some destination without passengers in our new vehicle, but fly just the same. There needs to be some tangible evidence that the project is capable of producing value for the customer on the planned day for the planned cost.

For the milestone to be met, we need to accomplish something that produces the value. These accomplishments are the entry criteria for delivering the capability. They are what enables the capability to exist. For each accomplishment, one or more “criteria” is used to assess the “done-ness” of the work performed to produce a product or a service.

The actual work that takes place on the project is contained in work packages, which hold the work activities, the resources needed to perform the work, and the measures used to assess the progress of the work as it is performed.

All three elements—milestones, accomplishment, and criteria—need to be in place before we can talk about the success of the project. If we leave one out, we will also be leaving out a critical piece of information needed to assess each of the Five Immutable Principles and our Five Practices will be weakened.

Implementing the Work

The next step is to perform the work defined in the work packages shown in Figure 2.3. The work packages are where the project team defines its activities. Whether it is writing code, bending metal, shoveling dirt, developing a drug, or teaching a class, they are all implemented through “work packages.”

The work packages contain the scheduled activities needed to reach “done.” This is where the actual work takes place to produce products or services. Figure 2.3 shows how these work packages are connected to another important element of our Five Immutable Principles—the work breakdown structure. We’ll examine the WBS further in Chapter 3, but for now, it is important to note that the WBS is a deconstruction of all the products and services needed to produce the deliverables for the project. The terminal nodes of this WBS are work packages that produce the project’s deliverables. In turn, these deliverables implement the capabilities for the stakeholders.

FIGURE 2.3 Work packages define specific activities leading to a capability.

While building a plan that delivers the needed capabilities, we also need to build a credible WBS. There are numerous books and resources that explain how to build a good work breakdown structure, but there are underlying principles that guide the development of a WBS. The WBS is a necessary project element and is defined, developed, and maintained throughout the system life cycle based on the disciplined application of a systems engineering process.

Some important attributes of a WBS are that it:

![]() Is a product-oriented family tree composed of hardware, software, services, data, and facilities

Is a product-oriented family tree composed of hardware, software, services, data, and facilities

![]() Displays and defines the product(s) to be developed and/or produced

Displays and defines the product(s) to be developed and/or produced

![]() Illustrates the elements of work to be accomplished and relates them to each other and to the end product

Illustrates the elements of work to be accomplished and relates them to each other and to the end product

Another critical attribute of a WBS is the MECE (mutually exclusive, collectively exhaustive) principle:

![]() Mutually Exclusive (ME). No subcategory should represent any other subcategory (“no overlaps”). In the WBS, this means the deliverables are unique so we can assign cost to them and determine who is going to develop them.

Mutually Exclusive (ME). No subcategory should represent any other subcategory (“no overlaps”). In the WBS, this means the deliverables are unique so we can assign cost to them and determine who is going to develop them.

![]() Collectively Exhaustive (CE). All subcategories, taken together, should fully characterize the larger category of which the data are part (“no gaps”). The WBS represents the “all-in” work. If it’s not in the WBS, it is not going to get done.

Collectively Exhaustive (CE). All subcategories, taken together, should fully characterize the larger category of which the data are part (“no gaps”). The WBS represents the “all-in” work. If it’s not in the WBS, it is not going to get done.

Building a good WBS does not start with defining the level of the WBS. It starts with the MECE principle and the resulting product (or service) architecture.

WBS building is systems architecture, in the same way technical design is systems architecture, for several reasons:

![]() We need to know which of the system’s components are mutually exclusive.

We need to know which of the system’s components are mutually exclusive.

![]() The subcategories of these components must be collectively exhaustive. Parts can be shared in the WBS, if the work for those parts can be shared, but they need to be assigned different WBS numbers, so it is clear that they are ME at the same time as they are CE.

The subcategories of these components must be collectively exhaustive. Parts can be shared in the WBS, if the work for those parts can be shared, but they need to be assigned different WBS numbers, so it is clear that they are ME at the same time as they are CE.

![]() The WBS can then be used to collect costs and answer the questions, “What does this part, subassembly, assembly, or system cost, and where does it fit in the overall project?”

The WBS can then be used to collect costs and answer the questions, “What does this part, subassembly, assembly, or system cost, and where does it fit in the overall project?”

![]() The resources (one of the Five Immutable Principles) are then assigned (not named by categories—names change when control changes; names of categories don’t change) and the Responsibility Assignment Matrix (RAM) built to see who is working on what, and at what cost.

The resources (one of the Five Immutable Principles) are then assigned (not named by categories—names change when control changes; names of categories don’t change) and the Responsibility Assignment Matrix (RAM) built to see who is working on what, and at what cost.

How to Assess Resources

Now that we know where we want to go, the next question is how to get there. How do we build the products or provide the services needed to reach the end of our project? There are numerous choices, depending on the domain and the context of the project in that domain.

All resources—internal and external, their dependencies, and any other items needed to produce the deliverables—are defined in the work packages. The work package manager is accountable for managing all these resources. If resources are not under the control of the work package manager, the risk to the success of the deliverables is increased because accountability is no longer traceable to a single person—violating the principles of the Responsibility Assignment Matrix. The RAM assigns accountability for each deliverable to a single person. In some development paradigms, there is shared accountability, but this is trouble waiting to happen. A single point of integrative responsibility is a critical success factor. That person can certainly “share” responsibility, but accountability is singular.

Planning for Resources

Planning the resources for a project starts with a Resource Management Plan. This is a written plan, driven by the work packages, stating the types of resources, number needed, and their need date.

This plan needs to address:

![]() The Demand Forecast. With the work package “owners” in the room, a full-time equivalent (FTE) demand model must be built. How many hours of work are planned for the work package? In the workweek plan, how many full-time staff does this translate into? This approach does not address (yet) productivity, specialty skills, availability of these skills, facilities, tools, or any other item needed for success.

The Demand Forecast. With the work package “owners” in the room, a full-time equivalent (FTE) demand model must be built. How many hours of work are planned for the work package? In the workweek plan, how many full-time staff does this translate into? This approach does not address (yet) productivity, specialty skills, availability of these skills, facilities, tools, or any other item needed for success.

![]() Existing or Proposed Resources. There needs to be an assessment of the on-hand resources, their availability, and their “effectiveness.” This is the first time we consider how effective the current resources are and how that effectiveness affects our project.

Existing or Proposed Resources. There needs to be an assessment of the on-hand resources, their availability, and their “effectiveness.” This is the first time we consider how effective the current resources are and how that effectiveness affects our project.

![]() Planning Assumptions. This stage of the plan is the start of risk management. Assumptions are those things that may or may not come true, those things that need to come true for the project to be a success, and those things that can’t happen if the project is going to be a success. Thus, Assumption-Based Planning asks questions about what the future might look like.7

Planning Assumptions. This stage of the plan is the start of risk management. Assumptions are those things that may or may not come true, those things that need to come true for the project to be a success, and those things that can’t happen if the project is going to be a success. Thus, Assumption-Based Planning asks questions about what the future might look like.7

![]() Future Resources. A forecast of future resource needs can be made in conjunction with the demand for resources in the form of an FTE model, the currently available resources, and the assumptions about the future demands for not only resources, but all aspects of the project. This is a probabilistic forecast indicating a confidence level for the needed resources. We’ll talk more about probabilistic forecasting, risk, and performance measures in Chapter 5 when we discuss Continuous Risk Management processes.

Future Resources. A forecast of future resource needs can be made in conjunction with the demand for resources in the form of an FTE model, the currently available resources, and the assumptions about the future demands for not only resources, but all aspects of the project. This is a probabilistic forecast indicating a confidence level for the needed resources. We’ll talk more about probabilistic forecasting, risk, and performance measures in Chapter 5 when we discuss Continuous Risk Management processes.

![]() An Integrated Resource Plan. Now we can start to build the Resource Management Plan. There are many templates on the web for this. Minimally, the plan contains a list of resources needed once you have assessed your demand, the availability of current resources, and the assumptions around those needs. Once you have assessed these, the equipment, facilities, and all the other nonpersonnel resources are assessed and planned.

An Integrated Resource Plan. Now we can start to build the Resource Management Plan. There are many templates on the web for this. Minimally, the plan contains a list of resources needed once you have assessed your demand, the availability of current resources, and the assumptions around those needs. Once you have assessed these, the equipment, facilities, and all the other nonpersonnel resources are assessed and planned.

![]() Short-Term “Call to Action” Plan. With the Resource Management Plan in hand, it is time to execute the plan.

Short-Term “Call to Action” Plan. With the Resource Management Plan in hand, it is time to execute the plan.

How to Handle Impediments and Assess Risk

Project managers constantly seek ways to eliminate or control risk, variance, and uncertainty. This is a hopeless pursuit. Managing “in the presence” of risk, variance, and uncertainty is the key to success. Some projects have few uncertainties—only the complexity of tasks and relationships is important—but most projects are characterized by several types of uncertainty. Although each uncertainty in our project domain is distinct, a single project may encounter some combination of the four classes of uncertainty:8

1. Natural Variation. These uncertainties come from many small influences and yield a range of values on a particular activity. Attempting to control these variances outside their natural boundaries is a waste. This type of uncertainty is labeled aleatory (variance-based risk) and is “naturally” occurring. It is part of the process, the culture. It’s just “in the air.” The key here is that it is not possible to reduce aleatory uncertainty. The only protection is to have cost, schedule, and technical “margin” to absorb these variances.

2. Foreseen Uncertainty. These uncertainties are identifiable and understood influences that the team cannot be sure will occur. There must be a mitigation plan for them. This type of uncertainty is labeled epistemic (event-based risk). The probability that a specific risk will occur can be created. This type of uncertainty and resulting risk can be “handled” in two ways. First, the risk can be “bought down,” or “retired,” by spending money to learn more information or doing work to remove the uncertainty and therefore the risk. Second, management reserve can be provided to protect the project should this risk occur. Management reserve (MR) is the amount of the total budget withheld for management control purposes, rather than assigned for the accomplishment of work. MR is held and applied through a disciplined process to any additional work that is to be accomplished within the authorized work scope.

3. Unforeseen Uncertainty. These are uncertainties that can’t be identified during project planning. When they occur, a new plan is needed to deal with the uncertainty and the resulting risk created by the unforeseen uncertainty.

4. Chaos. These uncertainties appear in the presence of “unknown unknowns” (UNK UNK). The concept of UNK UNK is overused and even abused. “We didn’t see it coming” is a common response. In fact, we were just too lazy to look for the risk. Our mortgage crisis, our lack of understanding of international politics, and our failure to adequately talk to the stakeholders are all examples of the misapplication of UNK UNKs.

Both of these uncertainties are related to three aspects of our project management domain:

1. The External World. These are the activities of the project that are impacted by events and processes outside the project (e.g., the weather, vendor performance, prices of materials, politics, and business cycles).

2. Our Knowledge of This World. These are the planned and actual behaviors of the project as we can detect them from observations, research, and analysis.

3. Our Perception of This World. These are the data and information we receive about these behaviors and how we interpret the data when making decisions about the risk created by the uncertainty.

There are consistent themes that contribute to the “less than acceptable” outcomes for projects that must be addressed by risk management:9

![]() Significant gaps in the risk management practices employed by programs and organizations

Significant gaps in the risk management practices employed by programs and organizations

![]() Uneven and inconsistent application of risk management practices within and across organizations

Uneven and inconsistent application of risk management practices within and across organizations

![]() Ineffective integration of risk management with program and organizational management

Ineffective integration of risk management with program and organizational management

![]() Increasingly complex management environment

Increasingly complex management environment

Each of these can be found on projects that got into trouble. The solutions are obvious in principle but hard in practice because the foundation for success was not laid in the beginning. Correcting troubled projects—triage—is difficult. It is much easier to start the project correctly by applying the Five Immutable Principles than to add them later to a troubled project.

Plans for Handling Risk

For the project to increase its probability of success, both uncertainty types—aleatory and epistemic—must be “handled.” The risk resulting from the uncertainties are first recorded in a Risk Register, along with the plans for handling them, the variances for the naturally occurring uncertainties, and probability of occurrence for the foreseen risks. The Risk Register is then assessed for its impact on cost and schedule. We need to determine the management reserve we are willing to commit to cover the known uncertainties and the resulting risk. We also need to determine how much schedule and cost margin we want to carry in the Integrated Master Schedule (IMS). The IMS is a term used on large complex projects. It contains all the work to be performed, the specific deliverables, and the planned budget to produce those deliverables. In Chapter 3, we’ll take a deeper dive into building the IMS. With these numbers, we then need to determine any residual risks and if there is sufficient budget and time to handle them should they also occur.

How to Measure Progress to Plan

Measuring progress is difficult on many projects. Some start by measuring how much was spent on the work performed. This, of course, just tells us if we’re on budget at any given point in the project. Sometimes, progress is measured by the passage of time. The current duration of the project divided by the total duration gives us the “percent complete.” These are all necessary measures of progress, but they are far from sufficient in support of the Five Immutable Principles. None of these measurements speak to what was actually done on the project in terms of our movement toward “done.” We know from earlier in this chapter that “done” is defined by the capabilities delivered by the project, whose units are MoEs. With the information from the four immutable principles already discussed, we now need to confirm that we are making actual progress, not just spending money and passing time with our fifth principle.

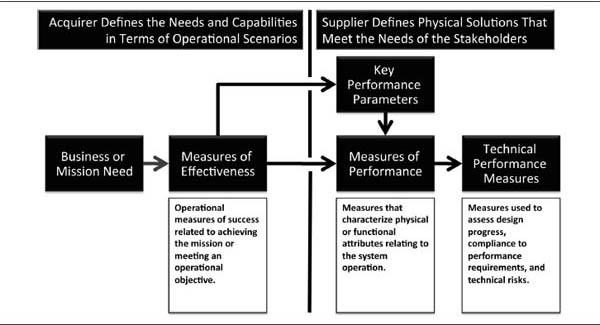

The key principle here is “planned progress.” We must predefine what progress we need to make at any specific point in the project, otherwise all we can determine is how much time has passed and how much money has been consumed. Preplanning progress is the basis of “performance-based” measurement for both project processes and technical products. As Kent Beck said, “Optimism is the disease of development, feedback is the cure.”10 We need tangible evidence through feedback on our progress. There is only one kind of feedback for projects—measures of physical percent complete. No soft touchyfeely measures of progress. No hand-waving measures. We need physical, tangible evidence of progress. Something we can actually show to the customer. Something that is compliant with the planned technical outcomes at this point in the plan. Figure 2.4 shows the connections between the measures needed for these principles.

These measures are independent of any product development methodology. For our measures of progress to plan on any project, we need to have the following:

![]() “Tangible evidentiary materials,” which means that there is proof of progress, not just someone stating that progress has been made.

“Tangible evidentiary materials,” which means that there is proof of progress, not just someone stating that progress has been made.

FIGURE 2.4 The work breakdown structure shows how progress is measured.

![]() Predefined existence of this evidence in meaningful units of measure established before work began. For example, if we wanted to use the weight of a bridge design as a measure of performance, we’d have our CAD model tell us the ranges of weights from the 3D solid structures model to be used to assess the final design weight.

Predefined existence of this evidence in meaningful units of measure established before work began. For example, if we wanted to use the weight of a bridge design as a measure of performance, we’d have our CAD model tell us the ranges of weights from the 3D solid structures model to be used to assess the final design weight.

![]() Progress defined in these same units of measure.

Progress defined in these same units of measure.

We’ll see in Chapter 5 how to put the measures in Figure 2.4 to work. Here, we will look a little closer at each measure.

![]() Business or Mission Need. This measure is a description of what capabilities the business needs to possess in order for the project to be successful. These capabilities state what “done” looks like in some form that is meaningful to the customer. For example, if we wanted to replace a transaction processing system with a cheaper one, we would define the target transaction costs before we started the development to ensure that everyone knows what “done” looks like.

Business or Mission Need. This measure is a description of what capabilities the business needs to possess in order for the project to be successful. These capabilities state what “done” looks like in some form that is meaningful to the customer. For example, if we wanted to replace a transaction processing system with a cheaper one, we would define the target transaction costs before we started the development to ensure that everyone knows what “done” looks like.

![]() Measures of Effectiveness. These are the operational measures of success that are closely related to the achievements of the mission or operational objectives evaluated in the operational environment, under a specific set of conditions.

Measures of Effectiveness. These are the operational measures of success that are closely related to the achievements of the mission or operational objectives evaluated in the operational environment, under a specific set of conditions.

![]() Measures of Performance. These measures characterize physical or functional attributes relating to the system operation, measured or estimated under specific conditions.

Measures of Performance. These measures characterize physical or functional attributes relating to the system operation, measured or estimated under specific conditions.

![]() Key Performance Parameters. These measures represent the capabilities and characteristics so significant that failure to meet them can be cause for reevaluation, reassessment, or termination of the program.

Key Performance Parameters. These measures represent the capabilities and characteristics so significant that failure to meet them can be cause for reevaluation, reassessment, or termination of the program.

![]() Technical Performance Measures. These measures are attributes that determine how well a system or element of a system is satisfying or expected to satisfy a technical requirement or goal.

Technical Performance Measures. These measures are attributes that determine how well a system or element of a system is satisfying or expected to satisfy a technical requirement or goal.

Measuring Planned Progress

Measuring progress alone is not sufficient to increase the probability of success. We need to measure progress made against planned progress. To do this, we must have defined what progress we should have made, using the measures in Figure 2.4, on a defined day or for a defined period of performance. This means that before the project can be successful, we need to know what “done” looks like in these four measures—Effectiveness, Performance, Key Performance Parameters, and Technical Performance. Without these, we will return to measuring progress to plan using the passage of time and consumption of resources.

Like our uncertainty and risk assessment, these measures of progress are probabilistic. They are driven by the underlying statistical process, and the margin of error should be indicated. It is not to correct to say we want to decrease the cost of process transactions; we need to say what the tolerance on the target value is. Is it $0.07 exactly, or $0.07 ± 5 percent?

Then we need to speak about these measures in confidence intervals. How confident are we that we can reduce the transaction cost to $0.07? Is it 90 percent confidence, 80 percent confidence? It cannot be 100 percent since projects are probabilistic “beasts” and no variable is deterministic.

A critical point here is that when someone provides you with a single point estimate, and doesn’t provide the margin of error or the level of confidence, then by default, it can’t be right.

Looking Back

In Chapter 1, we looked at the drivers of project success—the activities and the artifacts or the elements that pushed the project along its path to completion. In this chapter, we developed the notion of Five Immutable Principles based on those drivers. These principles are the foundation of successful projects in any domain, using any project management method, and any product development process. The project can test if the principles are being applied by asking five questions. Without credible answers to the five questions, the probability of success for the project is reduced.

Let’s ask the questions for the Five Immutable Principles again in slightly expanded form and examine what credible answers might be:

1. Do we know what “done” looks like in units of measure meaningful to the decision makers?

![]() Done needs to be measured as the capabilities provided to the buyer. These capabilities are derived from the business or mission needs. The capabilities provide the business or organization with the “ability” to do something new, something in support of its strategy.

Done needs to be measured as the capabilities provided to the buyer. These capabilities are derived from the business or mission needs. The capabilities provide the business or organization with the “ability” to do something new, something in support of its strategy.

• In our new insurance claims management system we need the capability to pre-process insurance claims at $0.07 per transaction rather than the current $0.11 per transaction.

• On our service mission to the Hubble Space Telescope, we need the capability to change the Wide Field Camera and the internal nickel hydride batteries, while doing no harm to the telescope.

• We need the capability to comply with new procurement regulations for selling to the federal government using the current ERP system and the supporting work processes in ways we have not done before.

![]() These capabilities are measured by their effectiveness to meet the needs of the buyer, either in terms of business effectiveness or mission effectiveness.

These capabilities are measured by their effectiveness to meet the needs of the buyer, either in terms of business effectiveness or mission effectiveness.

• The target of $0.07 per transaction will have lower bound of $0.06 and upper bound of $0.08 in a probability distribution. No transaction cost processed by the business rules will exceed $0.09 without manual intervention.

• After installation of the Wide Field Camera during Service Mission 4, the UVIS Field of Vision will be restored to <0.00014 e-/pix/s.

• Starting with our old procurement system (Catalog Sales), migrate all baseline cost of goods to the new procurement system (Engineer to Order) with 100 percent accuracy, within one accounting period, and provide customers access to the data at the start of the next business month.

![]() Successful project managers have a list of what capabilities are needed from the project for the customer, the units of measure of these capabilities, and where in the sequence of work each of these capabilities will be delivered and ready to use.

Successful project managers have a list of what capabilities are needed from the project for the customer, the units of measure of these capabilities, and where in the sequence of work each of these capabilities will be delivered and ready to use.

• Using an approach similar to that shown in Figure 2.2, document each milestone and support deliverables in a Concept of Operations or similar document.11

2. Do we have a plan to reach “done” on time and on budget?

![]() Our plan has to describe how we are going to deliver each capability and how we are going to measure the increasing maturity of that capability as it emerges from our work effort.

Our plan has to describe how we are going to deliver each capability and how we are going to measure the increasing maturity of that capability as it emerges from our work effort.

• A step-by-step migration plan at the top-level deliverables starts with a pilot that imports provider data and applies the new enrollment process. This will demonstrate that the legacy system data have integrity in the new system.

• Using the Wide Field Camera 3 Instrument Mini-Handbook Cycle 16 operations plan, define the integration and test data target results in work packages for each test suite.

• Define a product capability roadmap, describing the user interface for procurement and warehouse material pull processes that match the “engineer to order” guidance in FAR 15.

![]() Our plan is connected to the sequence of work activities that will produce the outcomes from the project. This work sequence is usually called a “schedule,” but it can also be called other things, as long as it states the order of work and the evidence that the work is producing an outcome.

Our plan is connected to the sequence of work activities that will produce the outcomes from the project. This work sequence is usually called a “schedule,” but it can also be called other things, as long as it states the order of work and the evidence that the work is producing an outcome.

• Using the structure of the plan in Figure 2.1 and Figure 2.2, construct a sequence of properly linked work packages to define the master schedule, with durations, resources, and risk retirement activities. Budget and resources are assigned to the work packages, making this a candidate to start the project. Changes always occur and, if accepted, are reflected in the schedule.

![]() Successful project managers have a plan and a schedule for producing the deliverables on the planned date, for the planned cost, with planned technical compliance to the specifications.

Successful project managers have a plan and a schedule for producing the deliverables on the planned date, for the planned cost, with planned technical compliance to the specifications.

3. Do we know what resources we need to reach “done”?

![]() Resources mean anything that we use during the project—people, facilities, consumables, external items.

Resources mean anything that we use during the project—people, facilities, consumables, external items.

• Resource assignment starts at the work package level and any conflicts resolve before starting the initial work. The work package manager initiates the resource-loading plan by identifying how many full-time equivalents (FTEs) are needed.

![]() The timing, location, quality, capabilities, capacity, and other attributes of these resources must be aligned with the need for them. This means there must be a plan for these resources similar to a plan for the project outcomes.

The timing, location, quality, capabilities, capacity, and other attributes of these resources must be aligned with the need for them. This means there must be a plan for these resources similar to a plan for the project outcomes.

• With the rough head count, skills and availability can be planned. This is an iterative process and cannot be skipped.

4. Do we know what impediments we’ll encounter along the way to “done,” and how we are going to handle them?

![]() Uncertainty is part of all projects. Managing in the presence of uncertainty is what project managers do.

Uncertainty is part of all projects. Managing in the presence of uncertainty is what project managers do.

• Managing risk starts and ends with the Risk Register, which contains the risk name, the probability of occurrence (for event-based risks), the cost impact if the risk “come true,” the cost of handling, the residual risk after handling, the probability of occurrence for the residual risk, the cost of handling the residual risk, and the impacts on work packages and deliverables.

![]() Uncertainty creates risk. Managing in the presence of risk means having a plan for how to handle both the uncertainty and the resulting risk.

Uncertainty creates risk. Managing in the presence of risk means having a plan for how to handle both the uncertainty and the resulting risk.

• Along with event-based risk (epistemic uncertainty), there is variance-based risk (aleatory uncertainty). Aleatory uncertainty creates schedule slippage and cost growth due to naturally occurring processes. No actual work ever takes “exactly” the planned duration. Materials, labor, and equipment have cost variances that must be considered. Aleatory uncertainty and risk are handled with margin or management reserve; for example schedule margin, cost margin, management reserve for “in scope” but unplanned outcomes.

5. Do we know how we are going to measure progress to plan in terms of physical percent complete?

![]() Measuring progress to plan requires tangible evidence. These provide measures of physical percent complete.

Measuring progress to plan requires tangible evidence. These provide measures of physical percent complete.

• The number of providers migrated from the legacy systems to the new provider system along with the data and the ability to enroll clients.

• The passing of the Built-in Testing of the camera’s on-board data processing systems that create JPEG images for return to Earth.

• Verification that product orders can be passed through the system and compliance with business rules verified for a statistically sampled set of parts.

![]() Opinion, professional judgment, the passage of time, or consumption of resources are not measures of progress.

Opinion, professional judgment, the passage of time, or consumption of resources are not measures of progress.

• Physically observing the claims processing system work on a “test suite” of data in the new system.

• Physically testing the camera’s capabilities and reporting the results on the test for the engineering staff to assess.

• Physical evidence of purchase orders and warehouse “pulls” for the sample data set.

![]() Only measures of physical percent complete against the planned physical percent complete at the planned time in the project are measures of progress.

Only measures of physical percent complete against the planned physical percent complete at the planned time in the project are measures of progress.

What’s Ahead?

With the Five Immutable Principles in place, let’s move on to the Five Practices needed to increase the probability of project success:

1. Identify the capabilities needed to achieve the project objectives.

2. Elicit technical and operational requirements needed for system capabilities to be fulfilled.

3. Establish a Performance Measurement Baseline for the time-phased network of activities needed to produce the project’s outcomes.

4. Execute the Performance Measurement Baseline, while ensuring that technical performance is met, risks are retired, and the needed capabilities are delivered.

5. Apply Continuous Risk Management to each work activity to ensure that the identified uncertainties and resulting risks are properly handled.