Transition, Failure, Resilience

Introduction

Eisenhower once said, “planning is everything, plan is nothing.” There is some sense in this sentence, especially in the current context of high turbulence with different industrial sectors converging and technologies disrupting the operations of companies. We have discussed at length in the previous chapters the era of transitions we are in and how to plan the development of our competences to succeed. But, what if we fail? This is the question we will be dealing with in this chapter.

Failure has always been part of any project, career, and business. The difference now is the potential frequency of failures. As the occurrence of transitions has increased, the same happens with failures, as a transition is, by definition, a very risky context due to its characteristic of radical change.

In this chapter, we will elaborate on the key risks each type of transition generates, how do we learn from previous failures, how do we get over future derailments, how do we work with ourselves if failure appears, and how do we plan our short-term objectives after failing. A key competence we will exercise during the failing process is resilience; therefore, it will appear several times during the chapter.

Leadership Pipeline, Transitions’ Cycle, and Resilience

If we look at the job market in the 1970s and 1980s, we could see that there has been much more stability than in the previous decades. People used to have longer careers in different corporations and professions. This is the reason why transition and resilience have become essential parts in any personal development program.

We have traditionally been talking about the so-called leadership pipeline that represented the changes in responsibility every individual was facing sequentially during their time at a company. The first step was usually as an individual performer, second as manager of other people or small teams of people, then managers of other managers, and the pipeline continues all the way to general manager.

This leadership pipeline used to take a relatively long period of time depending on the sector and the company, and the people had years to get ready for the next step. Though careers today face quicker changes, as we have repeatedly said, and tenure in one specific company might be shorter, the essentials of the leadership pipeline remain. Even freelancers, who are the ultimate individualistic performers, if they succeed, they end up creating their own team, startups, and a small company and then, the leadership pipeline starts. The difference between the current and the past pipelines is that the hierarchical structures have become more elastic and, in some cases, diffused.

The moral is that even in a context of continuous changes and predominance of careers outside large and hierarchical corporations, people end up facing a sort of leadership pipeline with all the consequences in terms of recognition, compensation, and responsibility.

As in any change process, the psychological resistance used to be the main barrier. Resistance to change is the consequence of our desire to stay in our comfort zone. We call it the wall of fear—the resistance to change in career development. The root of the wall of fear is both the rational recognition of my comfort zone and the irrational emotions in front of something that is uncertain. This is the reason why in order to cross it, we need both rational guidance and emotional support.

Coaching is a tool we will touch upon briefly in Chapter 11. Generally, it is one of the most recommended instruments, as it helps to have mental clarity and emotional support. As most individuals cannot afford the cost of professional coaching, companies should start looking at making coaching part of the benefits they offer to their employees.

Any transition generates fear. If we do not cross it or if we do it through the wrong side, we fail. Sometimes, we even cross it, but we derail as we try to continue behaving as we did in previous positions without the awareness that our context had changed.

Identifying Our Derailment Risks—An Exercise

Over time, our success as a leader will depend less on our individual skills and more on our ability to lead others. Unfortunately, leadership is one of the competences most individuals lack when they land in corporate careers.

Generally, our careers go at a fast speed, and the speed is propelled by our strengths. However, as the level of responsibility increases and our leadership impact unfolds, our strengths become metaphorically like the engine of a larger vehicle—a train! It means that those things that keep us on the direction, meaning the rails, at some level of speed might not be able to hold anymore. This is called the phenomenon of a derailment (see figure 9.1).

Figure 9.1 Train derailment

Source: (Aktaş 2018)

You can see next some examples of derailment found among professional managers that lead them to failure in their transitions:

1. People that have been perfectionists on their own tasks. This capacity to make things till the end and without mistakes might become a bottleneck for an organization once they become managers as they tend to be perfectionists not only with their own tasks, but also with responsibilities

2. People who are hard workers and are ready to go the extra mile in every activity they take; they could easily fall into burnout once the level of responsibilities substantially increases

3. People who used to be very creative and who can find new angles and visions for everything they undertake; they might create organizations without the necessary structure

4. People who are extremely result-oriented might be too harsh with their team members, which can really make it difficult their capacity to create organizations around their responsibilities.

These are only a few examples of derailment risks. Identifying this risk early in career and cultivating honesty can help to overcome the wall of fear when the needs of transitions appear.

Now, please turn to the exercise in your personal and career journey Leader’s Journal and start filling in your roadmap the derailment risks table.

Action Plan Contract—An Exercise

This action contract is similar in format to the previous chapter, now applied to a transition, so get ready for it.

1. Based upon our discussion on transitions and derailment risks, which are the 2–3 competencies you realistically think you need to focus to get ready for the next transition? Please, give reasons. For example: customer orientation because there will be a substantial increase of competition.

2. Please, specify 1–2 SMART objectives for each of the competencies you should develop.

For example: answer customers’ phone calls promptly and pleasantly.

“The most important thing to learn right now is to learn from failure. You will fail. Failure is essential for success,” John Riccitiello, CEO of Electronic Arts (Bryant 2011). Failure is part of success. It is something we have to know, and our competence development plan has to include resilience.

A good example is sport, which will help us introduce the need to grow in resilience. If we look at elite athletes, we will realize that they all have failed. That is the reason why we should try to emulate their competences in this regard. According to the research on recovery in sports, there are mainly two extrinsic motivational factors that help athletes to manage failure: the support of a coach and the social circle.

Researchers have also found up to seven motivational strategies that are useful in downturns among sportsmen: setting small goals or outperforming yourself, self-talk, setting priorities, keeping positive perception, self-observing, self-analyses and learning, and perceiving failures as a normal part of the process.

What is resilience? We define resilience as the capacity to avoid adverse mental and physical outcomes following exposure to failure or extreme stress.

There are, in fact, three potential dimensions of a response to resilience:

• Perspective: Once the failure has occurred, you have to get self-distance, realism, and acceptance.

• Search for meaning: It includes things such as looking deeper at what happens, observing an event in the framework of the big picture, focusing your objectives, and rebuilding what is necessary.

• Resources: When a failure occurs, we need to take factual stock of all the resources we have available in order to deal with it. We should care for all of them: physical resources, mental resources, personal competencies, and social relationships.

However, how to build resilience? Resilience is a competence, and, as so, it needs to be practiced. This competence allows us, in case of failure, to get the right perspective, to search for meaning, and to enlist the resources for proper decision making.

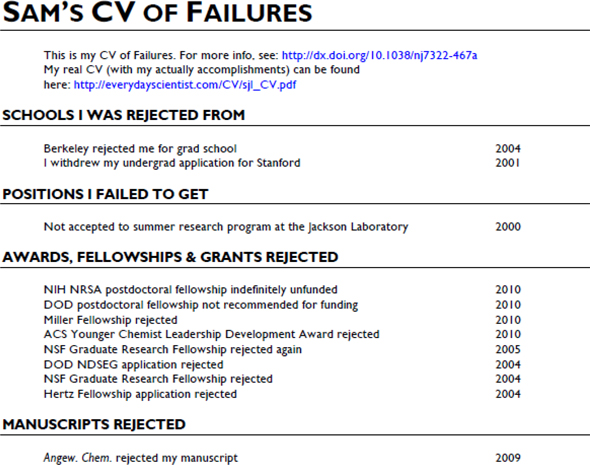

Part of the training in resilience implies a certain familiarization to failure. In simple terms, we need to develop the skin to get along with the emotional drama that comes along with the term failure. One way is to recognize those failures we had in our life, even though we have forgotten about them. The following exercise will help you with this.

Write a resume of failures, meaning those things that we have tried, but we have not achieved. Some organizations working in entrepreneurship used to require their participants to provide a record of the things their startups failed to do because it indicates the resilience, commitment to the project, and the learning capacity for the future. We offer to our students that they actually create the CV of failures. The task is very simple; they have to record failures in different areas of their professional careers. An example is provided as follows (see figure 9.2):

Figure 9.2 Sam’s CV of failures

Source: (Every Day Scientist)

Designing the Critical Event Review

A very effective tool we use in class in order to understand how to learn from failure, but also in general from any event is the so-called critical event review (CER). It is a highly structured essay-type assignment where the reader has to reply to open-ended questions. These questions have the following objectives:

1. Take stock of the different circumstances that surrounded the specific event

2. Analyze the different emotional and nonemotional reactions of the individual phasing the event

3. To think about what was missing in their reactions in order to deal better with similar events in the future

4. To conclude specific objectives for future events

The CER is a very powerful tool because it allows the individual to have more perspective of the event as he or she is self-distancing from it. He or she is taking a realistic perspective upon it, and he or she is embracing both the event and his or her reactions.

Critical Event Review—An Exercise

Please, create a CER of a failure you remember.

A CER should be between 200 and 500 words long; although you may find that you sometimes want to make them longer. The purpose of a CER is to focus on a specific experience and mine it for leadership lessons.

Structure of Each CER

The following framework provides the structure with which to reflect on the specific incident or experience.

Questions to consider

1. When

2. Setting

3. Who did I engage with? What happened?

5. How could others perceive it?

6. How did I feel?

8. What was the issue I was trying to address?

9. What did it remind me of? (Which previous experiences does it remind me of?)

10. What could I have done and said differently?

11. What did I notice during this experience—thoughts, feelings, body symptoms, and so on?

12. What am I resisting?

13. What is new, unfamiliar, or unpleasant?

14. How do I hold others accountable for how I am feeling?

15. What are the lessons in this for me?

You can juggle a lot more balls if you recognize that some balls are made of rubber and others are made of glass. Rubber balls bounce. Glass balls shatter. You can drop the rubber balls and usually recover easily enough. Drop a glass ball and you’re likely done with that one (Eblin 2017).

In this chapter, we have seen that transition and failure will be constant phenomenon in our careers and will eventually lead us to rethink our leadership capacities and will challenge our resilience. We also saw very specific tools in order to reflect on the different events surrounding transition and failure, and we have explained the needs of reviewing our derailment risks. There are three very strong potential derailers that we have to seriously avoid:

(1) Blaming others of our failures, taking the role of a victim

(2) Letting our emotions to take over the whole of our reaction, the CER tool that we have indicated in this chapter is a good instrument to prepare us for the future failures based on our past experiences

(3) Our lack of realism toward our experience that prevents many people from actually learning from their experience, and that could happen partially because sometimes we do not stop to look at what we have done and sometimes because our wall of fear is preventing us from going beyond our limitations