Case Study

Grace Lau

Grace Lau is a photographer working on the uses of photographs of the Chinese in the west.

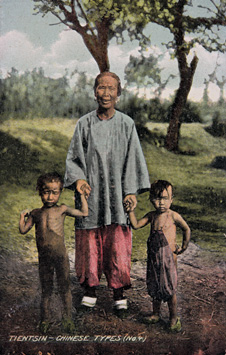

From the postcard collection of Grace Lau

© Grace Lau

FOR ME, THE MAIN IMPORTANCE of research is to provide factual and contextual information around the subject being covered in terms of its historical, cultural and current positioning. I trained as a documentary photographer and at Newport College of Art and Technology (now the University of Wales, Newport) we were encouraged to carry out library research into the issues that informed our projects. This was in pre-internet days so it was mostly based on looking at books, journals, magazines and newspapers; Newport had a lot of photographic monographs, with a big representation of Magnum members and also a lot of major American photographers. So, it mostly involved looking at photographic work and we were also encouraged to visit photography exhibitions and attend public talks and conferences on photography.

From the postcard collection of Grace Lau

© Grace Lau

When I started my career I was documenting contemporary fringe issues in subcultures, feminism and racism. Most of that work needed very little formal or academic research primarily because my personal involvement with the subject matter meant that I knew the issues and context well so could be there and take photographs without needing additional information. For the work on subcultures I went to the clubs, got to know the people, became part of the scene and copied their dress codes—for example, I acquired leather and rubber outfits (but no nipple clamps) and got a tattoo on my thigh at a tattoo convention. So I could, for example, photograph other people being tattooed. Feminist and anti-racist activity were central to the lives of all the people I met then and I was also part of that. At that time Val Williams was researching and writing about women photographers and when I started documenting women body builders Camerawork magazine invited me to write on gender issues and the body. I was also a member of the Steering Committee for Signals, the Festival of Women Photographers, which took place across Britain in the mid-1990s.

However, over the years my interests have developed into working on longer-term projects and looking at historical perspectives—on issues of race, in particular—and that has involved far more in depth research.

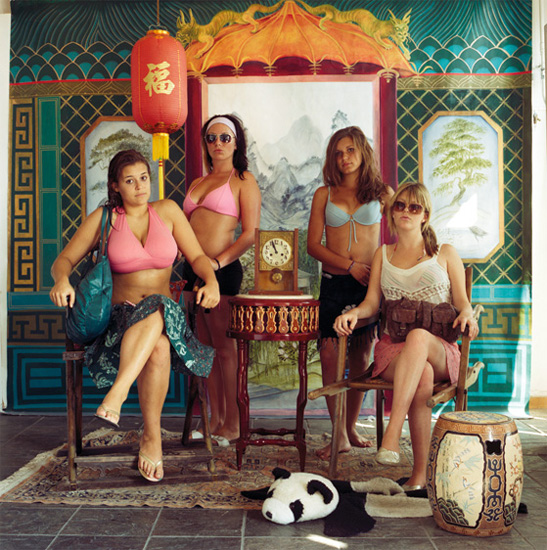

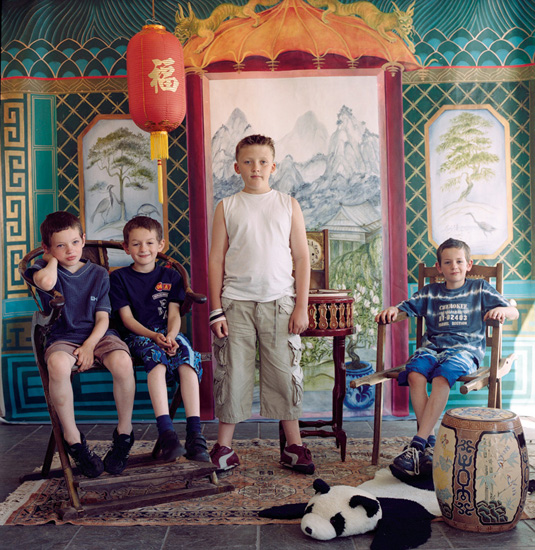

From 21st Century Types

© Grace Lau

When I start a project I look at other artists’ work on the subject, I also check their reference sources and do an online search, which will lead me to libraries and journals, which in turn lead to further reference sources. Funding has sometimes enabled me to take the time for really in-depth research but nowadays I never work on a personal project unless I have time for thorough research. In part, this is also because funders will support work that is backed by solid research.

For the last decade I have been working on the issue of cross-cultural influences between China and Europe since the invention of photography. I started in 2004 when a writer colleague in Shanghai commissioned me to write a book on early western photography in China. Research for the subject was an immense undertaking. Colleagues in London and Shanghai proved to be a generous source of research materials; they included Dr Frances Wood, head of the Chinese Department at the British Library, and Lynn Pan, who is a writer and scholar of Chinese history from Shanghai. I used archives at the British Library, the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), the Wellcome Collection, the Getty Collection, Magnum Photos and missionary libraries. The Wellcome Institute has original glass plates from John Thomson but I spent more time with the missionary societies because they were so very generous with their time and in letting me use their images. I also read a lot of the missionary journals, which were fascinating and detailed things like how they taught children British manners, the hardships and illnesses the missionaries suffered, the food they ate and wonderful details of their daily lives. So, in part my selection of archives was dictated by the levels of helpfulness I met with and their costs for loaning pictures for reproduction.

From 21st Century Types

© Grace Lau

I also accessed private collections including that of Michael Wilson, based in London and San Francisco, whose collection of vintage works includes William Saunders and Felice Beato and that of Régine Thiriez, based in Paris, who has the largest collection of vintage Chinese postcards in the world. Her interest in postcards triggered mine because she pointed out their significance—thousands of cards were printed in black and white or hand tinted and sold as souvenirs to travellers so they form an unique record of the connection between China and Europe and show how ‘orientals’ were viewed by the west.

This led me to a desire to see how the images had originally been used originally in the books that had first published the pictures and I ended up trawling secondhand bookshops, mostly in London, for historical information. I noticed that some books included images that had been published as postcards and that also sent me to scour postcard fairs all over England where I located early twentieth-century postcards, mostly featuring topography, portraits, missionary work and ‘exotic’ punishments. The inherent racism of these became immediately evident, for example Chinese workers were described as beasts of burden on one card, another was captioned ‘Chinese types’.

During this period I was looking at studio portraits of the Chinese by, for instance, English photographers John Thomson and William Saunders, who both set up portrait studios to photograph the diversity of Chinese society, I became aware that the subjects had been selected to typify Chinese types and were, for example, most commonly courtesans, coolies and opium smokers. The photographers all used the conventions of western formal studio backdrops and props such as pot plants and chaise longue and the images fascinated me and stayed with me after I’d finished the book. So, my research for my book Picturing the Chinese1 led directly to my developing the personal photographic project 21st Century Types where my aim was to subvert the Victorian traditions of these portraits by constructing an imagined Chinese portrait studio of the Victorian period in which I could photograph contemporary ‘western types’.

‘Chinese Types’ from the postcard collection of Grace Lau

© Grace Lau

It is essential to get facts right before you start on any body of work addressing issues because, consciously or un consciously, you are going to have a point of view and you need to be able to support and defend it if necessary. I do not believe it is possible to be objective in photography. When you start on a project you have to be very clear about your intended message and this will make it easier to find relevant resources and stop you from researching too widely or without purpose.

So, I’d include researching historical, social and cultural facts but also opposed positions and opinions which form the bedrock from which you develop your own perspective and piece of work. Then I look at other imagery from differing points of view—you need to see how other artists and photographers have dealt with the same issue—so I look in books, magazines, exhibitions and online, which helps me find my own route or shift my position if there’s a danger of duplicating what someone else has done.

My starting point for 21st Century Types, before I undertook the research described in question one, was to read Elizabeth Edward’s Anthropology and Photography because she talks about types and the way Victorian scientists measured up primitive peoples.2 She talks about photography as a political tool and how it was used to dominate and control colonial peoples and show the supremacy of the white race and this influenced my initial ideas on the subject.

So, you need to get all these things clear before you start or the danger is that the work itself will be the route through which you sort your position out and it can end up being quite inconsistent or not holding together well.

I have always relied on film rather than digital and used both 35mm and mediumformat cameras and am familiar with them so I don’t do much in-depth technical research because its not really necessary for what I do. But, for an instance of practical research while exploring Victorian portrait photography, I was reminded that photographers all used heavy cameras set on heavy tripods with slow film so I duplicated this to the best of my ability using my Hasselblad medium format camera set on a tripod with slow film. This also made my subjects more comfortable with being asked to pose in a formal way in a studio setting because I explained that this was an old-fashioned portrait studio and they had to be still, without smiling, and look straight at the camera. They were familiar enough with Victorian portraiture to understand exactly what I meant so it gave them a more participatory role in the tableau. Having researched Victorian portrait studios in England I showed my sitters some of these images, most of which were postcards, and generally they enjoyed the performative aspect of the shoot. They were also pleased and felt involved because they knew I would give them a digital print afterwards.

There are several ways in which the research I do impacts on my work and it is not always predictable. Having looked at how other people address the issue means I sometimes have to shift my approach; it’s important that the work looks visually different even if the message is similar.

From 21st Century Types

© Grace Lau

So, for example, knowing August Sander’s3 work People of the 20th Century helped me shape my thinking about social typology in the twenty-first century but I didn’t want to duplicate his approach and did want to make reference to the Chinese studio portraits of John Thomson and William Saunders, which is why I built an elaborate set rather than using a background relevant to the sitter’s profession, as Sander tends to do. Looking at Sander’s use of quite simple backgrounds inspired me to focus more on how my studio background could reveal more of what I’d learned in my research. And thinking about Sander’s portraits meant that when people wandered into my studio with the tools of their trade, their shopping, sunglasses, mobile phones, ice creams or biker’s helmets I encouraged them to pose with them rather than leaving these things out of the picture as most of my sitters expected me to ask them to do. This helped point up the differences between the nineteenth and twenty-first centuries.

But it’s more than that—the research tells me what to photograph and focuses my interests around what I have to say. The process of making a piece of work would be a lot more random and exploratory without that concentration that the research brings.

Looking at other people’s work and collecting information and ideas inevitably forces one to sharpen and focus one’s own work and ideas. For me, research is almost more exciting than the actual practical work of making images because, after the first level of basic research, which supports and quantifies my project, has been completed, there are almost always other research results that lead me in another direction or enhance my project in some other way. So, the research work leads the practical. For example, researching the Victorian tradition of dressing children in their best for post-mortem photographs led me to asking my subjects in my current project, Ad/dressing Death, to pose wearing their favourite clothing in which they would want to be remembered. Thinking about the children, who were usually posed as if asleep, led me to the idea that I wanted to see if I could show how our contemporary attitude to death has shifted now that the idea of the after-life is less prevalent so I make it plain that these are imagined post-mortem photographs by asking my subjects to pose in a coffin.

I was aware of the problem of the societal taboos about death but reading Photography and Death by Audrey Linkman4 and looking at the ways other artists and photographers, for instance Andreas Serrano, Elizabeth Heyert and the contributors to The Dead exhibition at the Barbican Art Gallery,5 have addressed the issue encouraged me to proceed and freed up my ideas to make my own exploration of what death means today. But the project came to an abrupt halt last year when four close friends died suddenly and unexpectedly. This brought it too close and made it impossible for me to do further research work so, despite the fact that I’d argue that it’s impossible to be objective, I do believe in maintaining a critical distance from the work.

The research and the practical go hand in hand. I don’t stop researching when I start photographing and so that ensures that I am constantly evaluating the work as a project develops. I keep a record in the form of a workbook with notes, references and reading resources and also log comments and critical feedback from colleagues and refer to it from time to time.

I work in the art world so the outcome is almost always going to be a publication or exhibition. 21st Century Types is both an exhibition, which has toured, and a book. The work is on temporary loan and hanging in the High Sheriff’s conference room in Lewes County Hall; this very formal setting was an entirely unexpected venue but I wouldn’t have changed anything had I known the work would end up there.

If I were a commercial photographer I would feel bound to consider audience as a priority but, in fact, I don’t think a great deal about audience because I think it would weaken the work if I tried to tailor it to meet people’s expectations. However, I do show work in progress to colleagues whose feedback I value and that always brings the possibility that I might change some aspect of the work in response to their comment so I consider them as audience although they are both well informed and supportive which is, of course, not going to be true of everyone else who sees the work.

Issues like gender and race are always there in my work because my work is subjective and these are the issues that motivate me most. I take pleasure in subverting the stereotypes that make these issues such rich areas to explore.

I don’t think you can ignore the role that chance plays in research. For instance, when I was mulling over the idea of a painted backdrop for my portraits I visited Brighton Pavilion6 and instantly saw how a version of that could be recreated to provide an appropriate and highly decorative ‘Chinese’ backdrop for my portraits. It was then an easy task to find an artist who worked painting backdrops for the theatre to produce an imagined nineteenth-century Chinese one for my studio.

Additionally, I believe that the wealth of material researched in one particular project can lead to new projects and directions. For example, the varied portraits I made during my first major work7 led me to take a deeper interest in the contemporary genre of portrait photography and in how this could shift from literal representation to artist’s interpretation. My continued reading around the art of portraiture informed the portraits I made for 21st Century Types and Ad/dressing Death.

Interview by Shirley Read

Notes

1 Grace Lau (2008). Picturing the Chinese: Early Western Photographs and Postcards of China. Hong Kong: Joint Publishing (HK) Co. Ltd.

2 Elizabeth Edwards (1994). Anthropology and Photography. New Haven and London: Yale University Press in Association with the Royal Anthropological Institute, London.

3 August Sander (1876–1964), German photographer best known for his portraits of Germans from a wide variety of social and economic backgrounds and for the organising principle behind his (unpublished) book People of the Twentieth Century in which he grouped his subjects into seven types (The Farmer, The Skilled Tradesman, The Woman, Classes and Professions, The Artists, The City and The Last People).

4 Audrey Linkman (2011). Photography and Death. London: Reaktion Books.

5 Andres Serrano, The Morgue, Portfolio, number 21, Edinburgh 1994/5. Elizabeth Heyert, The Travellers: post mortem photographs, Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York June–July 2005. The Dead curated by Greg Hobson and Val Williams, Barbican Art Gallery, London 1995.

6 Brighton Pavillion, built 1789–1823 as a seaside retreat for George, Prince of Wales, is remarkable for its magnificent ‘exotic oriental appearance’ and its collection of chinoiserie.

7 Grace Lau (1997). Adults in Wonderland. London: Serpent’s Tail.