Case Study

Susan Derges

Susan Derges uses camera-less photographic processes—often working in the landscape.

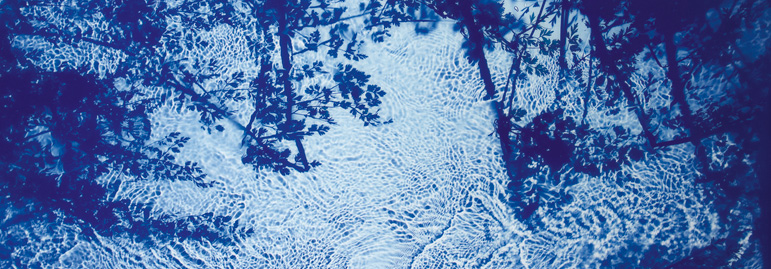

I‘VE NEVER REALLY CONSIDERED myself as doing research. My ideas usually require me to find a very particular way of making that embeds the ideas within it. An example of this was the River Taw photograms.

The ideas behind the project were about becoming close to the element of the river, as a metaphor of immersion and participation. I was looking to be part of it and so the process that I adopted for making that work was to actually immerse the photographic paper in the riverbed, in the flow of the water. This is quite a clear example of the kind of research process that I follow.

To expand a little further, the process of making feeds back into the idea and informs it, usually in surprising ways, so that it’s an ongoing enquiry rather than an idea that first needs to be researched and then manifested.

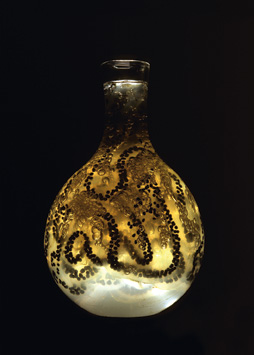

Vessel. 2001 light display transparency 16x12 inches

© Susan Derges

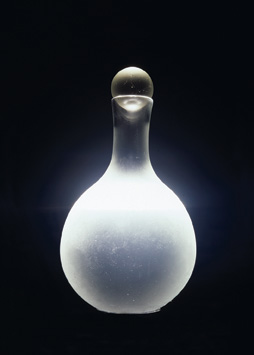

Sublimatio. 2001 light display transparency 16x12 inches

© Susan Derges

For that instance of immersion, I was seeking out a state of immersion in myself, looking for a way of not being a voyeur with a camera gazing at an object through a lens. It was a desire to be more connected with my subject matter. And through this desire for an immersive state the idea came to use paper in that way.

The idea is never clear at the outset. I don’t begin with a totally clarified concept but more of an intuition of something that I’m trying to articulate. It is sensed; the territory of it is defined but not completely distinct. So, the process of researching or investigating an idea, which I use as a method of testing the idea, is the process by which the nature of that idea becomes clearer to me. The research will disprove some of it and back up other parts, fleshing it out in surprising ways. The process of research is part and parcel of an idea coming into full fruition or formation.

Another example is my current body of work Tide Pools, the initial impulse of which was a dream. The dream touched upon themes of impermanence, fragility and change. The rockpools presented themselves to me as supporting those concerns and a whole process of exploring how to work with the pools then unfolded.

I made several series of images in specific locations, which led to my removing subject matter from these places, into the darkroom. Then, with the advice of a marine biologist, I began animating these things in a recreated water environment, which I could study more closely.

This involved exploring how to work with specimens, sea creatures, water-flows, movements and simulations of tidal surges. I was building up a whole picture of this changeable fluid environment; learning how I might work with it to explore that initial idea that I was groping towards articulating to myself.

Aeris. 2001 light display transparency 16x12 inches

© Susan Derges

Quite often, my knowledge isn’t sufficient to encompass what I need to know and rather than learning about it alone, I will seek consultation or sometimes collaboration, as I have with working with a marine biologist on Tide Pools. Neither of us knew at the outset how it was going to unfold. It developed in a very particular way because of our different areas of expertise, and her sense of what I might need to know.

Observer & Observed. 1991 Silver gelatin print 34x28 inches

© Susan Derges

Another element in parallel to this is a contextual search; questioning the frameworks of, for example, the cases that I’m working with. I studied a lot of material relating to the themes, both in historic and contemporary contexts, as well as in science, literature and the work of other artists. I learnt that Jeff Wall had made a huge glass tank that he kept populated with marine creatures in his studio for a period of time—I had no idea that he was doing that! I’m not sure how he had illuminated his but it was interesting that he had covered some of the same ground and had worked with marine biologists to maintain this environment.

Comments from critics have been incredibly helpful leads into some of the other ideas I’ve been dealing with. For a current project regarding boats, David Chandler described how in Sweden, in relation to rituals around mortality, sailing and the sea, ships were suspended from the roofs of churches. These floating talismanic objects were loaded not only with their relationship to water but to death, safety or fragility, either through being on or traversing water. This fed into my thinking about boats being in the sky whilst at the same time on water and in a transitional state; so becoming another metaphor for mortality, vulnerability, change, loss and other similar themes.

There has to be an intuition first, otherwise the research gives you nothing. It has to be led by the intimation of an idea but one must be prepared for the research to take you into the unknown and away from it, in order to bring you back to it again in a stronger more amazing manifestation. That, for me, is the kind of process that seems to go on in making work, when it is functioning well.

I often begin with something that is unknown to me that I have a sense I need to know about. I’m trying to dig into the unconscious and into to the unknown and that, I think, is very different to how a scientist would begin. They would define a hypothesis that needed to be explored through research methods and proved. It would be much more consciously articulated than the way that my work happens. In the past I have called what I do unfolding enquiry and this is now (especially within academia) termed research. I think there’s a difference between academic scientific research and the way that I use research.

River Bovey 2. 2007 Ilfochrome photogram 24×67 inches

© Susan Derges

There are parallels but I am dealing with my unconscious as much as my intellect. In science, research is about contributing to consciously articulated bodies of knowledge, whereas for me it’s a more poetic activity, more to do with the processes of imagination. It’s certainly not conceptually driven. I think many artists are conceptually driven and the term ‘research’ is valid to their whole way of working.

I begin with an intuition or a sense of an area that I want to explore but it’s not fully conscious. At the very end, the way in which I evaluate what I’ve done and how I edit out certain images and include others depends on whether I’m moved and convinced in a quite visceral or intuitive sense. A piece of work might well do the job but if it doesn’t move me I don’t use it; if it doesn’t speak to me on multiple levels then I’m not really interested in it.

It has to be more than just an intellectual statement, it has to have the potential to be very much alive and it’s quite difficult to articulate what those ingredients are that make the difference. I think what often does make the difference is the degree to which one has let go of the known and been open to trusting what’s coming in during the period of the research and development and been led by it.

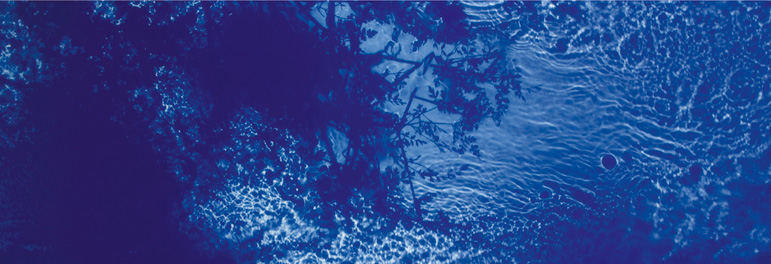

River Bovey. 2007 Ilfochrome photogram 24×67 inches

© Susan Derges

The Observer & the Observed is a good example. I was fascinated by the notion of the observer and the observed as it’s discussed in physics where, in simplified terms, how you set up an experiment to look at an electron will actually determine what you see. If you set it up one way you will see a waveform and set up another way you will see a particle; and both are reality! That paradox absolutely fascinated me because it takes us into a very, very creative relationship with the world.

As a maker, it suggested parallels with photography, which is not a neutral gaze; how you frame, set up and do something photographically is going to determine the result. That inability, the impossibility of making a neutral statement which you can say is the truth, is all relative and I was very interested in that kind of relativity. I decided to find a way to show this phenomenologically and I appropriated this small experiment that I found in an early science book, which took water and a little musical fountain, as an example of a visual paradox.

You take a flowing jet of water and, in the era when this experiment was made, it was vibrated by a tuning fork and illuminated by a magic lantern that had a card spinning in front of it so that it flashed on and off like a strobe. The vibration of the water, when it synchronised with the vibration of the light created the visual illusion of tiny droplets suspended in time and space. Yet when you turned the light on full and constant you just saw a jet of water and the drops disappeared. And then you’d set the strobe up and you could put your fingertips in between two droplets and they’d be wet so there was water that you couldn’t see running in the gaps.

That experiment was such an extra ordinary thing to set up and witness—it was a complete enigma. I did a lot of research, spending days and days making really boring documents of water drops or jets suspended in space. They were so banal; they just looked like quasi-scientific photographs. But then at one point the shutter jammed in my camera, which was behind the jet, and I looked in front of the jet and at the moment when my face came into view, the shutter released and a picture was taken. I didn’t think anything of it at the time but when I went through the negatives my face was blurred in the narrow depth of field of the image but totally focused in the little drops and suddenly the observer was there in the observed. It was a kind of perfect way of making that ambiguity manifest in the image.

The prints operated in the same way; if one stood a long way back one just saw a face but then people had a shock when they moved closer and the face disappeared into a blurred backdrop and suddenly small perfectly focused faces became apparent. I think that’s just maybe the neatest example that I can give of the research process. I couldn’t have calculated how to do that or predicted it. It happened as part of the process of my research.

In terms of projects where research has been less important the River Taw body of work, again, is a good example. I made a very intense initial study of the technical implications e.g. immersing photo-paper in water in the landscape at night, testing exposure times, distance of the light source from the paper, depth and speed of flowing water, speed of the burst of light of the flash and methods of housing and transporting the prints.

Once that was finished then the whole subsequent period (which lasted several years) was all about the making. Further research was made following a course of the River Taw over the period of a year and taking paper to the shoreline and exploring different weather conditions as well as moon cycles and wave, tides—it was making although, yes, it was also research—but I would say I wasn’t so conscious of conducting research, I was just making.

For the project Natural Magic, I was in residence at the Museum for the History of Science in Oxford. I began again with reading, initially into natural philosophy and the work of Giovanni Battista Della Porta (the first person to describe the camera obscura).

The whole process of research on that project was probably the most collaboratively conducted research that I have ever carried out, both in terms of practical, theoretical and literary input and consultation with the curators of the museum.

Following my discovery of alchemical apparatus in the building I worked with a glassblower in the Chemistry Department in Oxford University, who fabricated facsimile vessels, to animate a very early scientific experiment of the distillation process for making aqua vitae.

I then collaborated with an installation consultant who facilitated the placing of light boxes and objects within the scientific displays of the museum, to create the magical atmosphere I wanted to convey. It was a very consultation-heavy research project that gave me a huge amount of material to work with in subsequent projects. I fed off that research for many years after that.

That project was quite different to anything I’d done before. I was working with a large 5 x 4 camera and flashlight, illuminating vessels from within that were bubbling away. I had to learn an awful lot about photography that I hadn’t required before. To deal with ideas of the dark box and luminous, magical objects, in front of it meant developing a whole new idiom for that work.

Themes dealing with fluid processes have run through all my works. Translucency, internally illuminated imagery are common to The Observer & the Observed, the River Taw and the work in Natural Magic, as well as my current work. I think there are ways of looking at the world from a slightly unfamiliar perspective, a non-perspectival space, a translucency of internally illuminated things, which provide a more imaginative reading. The ways in which I might need to work with each project can vary hugely; an awful lot of work and time that gets invested in each body of work isn’t seen.

I think contextual research is less connected with the demands of the discipline and more driven by the nature of the subject. I am always led by the subject in terms of what needs to be done but then also I look at as much work as I can both in historic as well as contemporary contexts.

With my current research project, Tide Pools, I looked at the early prints of Philip Goss and other artists dealing with marine subject matter, natural history illustrations, Victorian nature prints, Anna Atkins’ cyanotypes, all of the early photography recording specimens—there was a huge enquiry into rock pools and shoreline and natural history in the nineteenth century. So I inform myself about that background whilst looking at contemporary artists’ treatments such as that of Jeff Wall and his marine environment.

I look, as well, at some of the ecological connections that resonate within my area of practice. I’m very interested in how the environment, for example, is articulated.

There will probably always be, for me, an area of interest in philosophy whether it be spiritual or more general, to inform the world-view that I have on the things that I am depicting. In terms of social concerns, I’m very aware of an approach that is non-reductive or a non-mechanistic existen tially limited approach to art making.

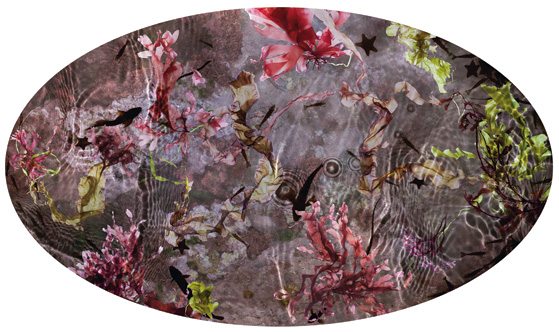

Tide Pool 28 2015 digital c type 48×24 inches

© Susan Derges

I’m trying to contextualise my own experience within a wider understanding of how people experience the world or what their questions are about life or death. I guess there are a number of different contexts that would be relevant. I’m definitely not placing myself within any religious context. That whole area of dogma and religion is not something that I feel comfortable with but there is a non-mechanistic, non-reductive concern that is often expressed well in Eastern thought and I find that helpful in terms of a more profound approach to the things I’m concerned with.

In terms of gender, I am aware there is an element where I am working of a feminine component. I think the preoccupation and ongoing connection with moon, birth or life cycles connotes a kind of womb-like space. That’s a very visceral, felt connection with the natural world and it feels very close to me. It’s not that this kind of territory is privileged to females but it’s likely that someone who has sensed that relationship on a very primal level would explore it in a slightly different way to someone who approaches it rationally.

Sometimes, I wonder about my showing work in contexts with makers who are male. I think there is some slight difference—something to do with a more chaotic rather than a conceptually planned conduction of the making of work. I do think I’m involved with something that’s more fluid and I sense a difference but I haven’t been concerned to articulate just what that is, or to take a stance in terms of the gender of my co exhibitors, usually because it’s not the primary concern or subject of the work. It’s a human thing—just where I come from and where I live and how I live my life everyday and particular to me.

I often find it unhelpful to think about the end result and how it will communicate at an early stage in the formulation of a project. Once the process is progressing and I have tested it against my own response, then, I believe there is a point when I can question it, and only then will I think about presentation; it’s left open for as long as possible.

With the current work, I wanted the pieces to be much more objects in themselves, smaller, unique artefacts in their own right, rather than framed prints that could be any scale. They’re very specific things.

I write a lot at the outset of a project. I keep a notebook recording technical notes and tests that I’m making in my work, so that I can refer back to a particular image and understand how it was arrived at. I keep a second notebook for more open, free writing, a sketchbook of ideas. I keep a lot of images now on the computer whereas I used to keep them in boxes of rolled prints; plenty of rejects set aside to be looked at again later, to inform where I’ve got to with the work and whether anything can be used and pulled out of those failures. These failed images are often highly informative—keeping them is an important part of my process.

Regarding evaluation, the work has to be technically completely resolved but there needs to be something that will hold my attention beyond just the reading of the idea. I think that’s where I really think strongly about the audience; I wouldn’t expect an audience to keep looking at a piece of work if all I was doing was illustrating an idea. One wouldn’t demand that something holds attention for any length of time if that’s all it did. I think of it as being like a trigger; I’m not telling someone how it is, I’m triggering them to open up to their own experience to either remember or grasp and explore a set of imaginative or reflective processes. It has got to catalyse an internal event in the other person. It’s very much about an exchange or communication.

The River Taw project was very intuitive in the way it evolved, I didn’t conduct that period of activity in the ways that I have my other projects where there was more rigour involved. I was continuously making notes but it was also very much led by the process itself. The weather, the tides, the moon cycle, all of these external conditions determined when I would be making the work and at what times, so it was quite different to making an actual research study into something. It was as if something was telling me what to do and I wasn’t in control, whereas with the darkroom work such as The Observer & the Observed and the current work, I’m far more in control of a process that is not governed so much by chance.

With the River Taw I was very interested at that time in all the writings about chaos and living life on the edge of chaos and being a participant in some broader movement rather than an independent author of something. I was reading a lot of work about complexity and chaos and was fully prepared to relinquish control of how the work unfolded. Of course, one can never do that completely but there was a willingness to open it up to the wider forces within which I was working—the environments that I put myself into.

I don’t talk about it as being research. It’s like what I do with my life—it’s a total thing. I’m sure many other people researching in all sorts of fields are equally dominated by their research and the processes that they have to employ for doing it. I don’t think historically that this kind of terminology has been applied to art practice. I don’t think of any of the people I look at as being researchers and I don’t see them publishing papers; I see them being compelled to do something because of their philosophy or their world-view or life experience and going about doing it in ways that only they possibly can. That feels quite different to a delineated kind of activity that I think of as being research. If art practice is currently regarded as research, then yes, in that sense, I suppose everything I do is research.

I think it is important to say that creative research can get really tampered with when it’s made to address certain outcomes. That could be the need to publish within certain periods of time, or the need to show too regularly or produce work for art fairs or publications for example.

I think there’s a lot of compromise, and mediocre work gets turned out in both academic and commercial areas because people are made to address totally inappropriate targets. That’s the same with residencies; they are too often run on the basis of what the outputs are going to be with ridiculously short time spans, so that people feel compelled to jump through too many hoops. It’s just an ill-informed understanding of what’s required to do in-depth research on the part of the people doing the commissioning, because this kind of research is different to just production. I feel that’s very important to make clear and to protect the wider processes of the research component.

Interview by Sian Bonnell