Case Study

Mandy Barker

Mandy Barker’s work explores the impact of marine pollution.

THE MOTIVATION FOR MY WORK is to raise awareness of plastic pollution in the world’s oceans and the harmful effect this has on marine life. Because the ideas for my work are drawn from quantitative scientific data, it is important that I have a sound understanding of the facts; so, knowledge gathering prior to developing a body of work forms an essential part of my practice.

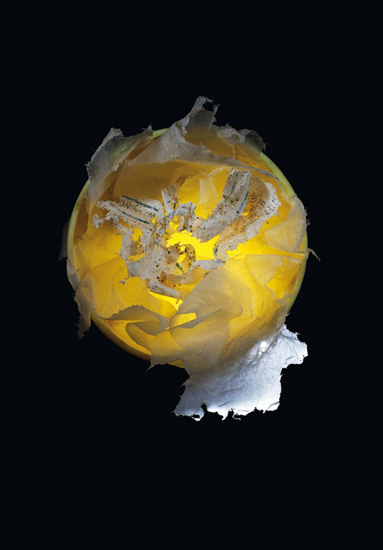

Plastic Bag: 1–3 Years. From the series: Indefinite.

A person uses a plastic bag for an average of 12 minutes before disposal. When a bag enters the sea suffocation or entanglement may occur but ingestion is the main issue. Sea turtles often mistake bags for their favourite food of jellyfish and squid when seen floating in the water column.

Photograph by Mandy Barker, 2010.

There is, of course, a considerable amount of information available in the literature (scientific journals and online), but working directly with oceanographers and ecologists who are studying the problem first hand is a key aspect of the research process for me. Developing such relationships has extended my knowledge of biodiversity around the world and allowed me to understand the extent of the problem in detail. For instance, I would never have known that hermit crabs in Taiwan use bottle tops to make their homes unless the experts had alerted me to these facts and explained them to me. It is this level of detail that informs my work.

But dealing with factual information also brings with it a keen sense of responsibility. The work I make has to be accurate and align with the scientific evidence if it is going to fulfil its purpose. So, for example, representing something that wasn’t happening or real would be out of the question. Being alert to my ethical responsibilities is essential to the integrity of my work and something I feel very strongly about.

And part of my role is to reciprocate the trust shown to me by the scientists who have supported me. I have an obligation to ensure that I do not to distort information purely for the sake of making an interesting or aesthetically pleasing image. Although aesthetics are important to the work I create, it has to do something more than simply look good; it has to be grounded in facts.

I see myself first and foremost as a photographer not an environmentalist, and my commitment as an artist is to transform the science into something visual and create artwork that is accessible and relevant. My interest in the environment stems from my childhood when I used to wander the beach collecting driftwood and other natural objects. Over time I noticed that there were fewer natural objects and more plastics and other manmade items washed up on the shore, which was shocking to me and this was something that I wanted to make other people aware of. To make that happen it is crucial that my work reaches as broad an audience as possible.

Initially, my early work began by my simply taking photographs of objects on the beach where the tide had left them. But because we are all so familiar with that type of image they failed to have any impact, and people by and large ignored them.

Plastics: 400 Years. From the series: Indefinite.

Plastic never biodegrades, it merely breaks down into smaller fragments. These micro plastic particles and fibres are found in filter-feeding barnacles, lugworms and amphipods, which are in turn eaten by larger sea creatures including fish, and ultimately humans.

Photography by Mandy Barker, 2010.

My challenge was to find a way of holding people’s attention by creating images that encouraged them to think or to engage with the work more actively rather than simply to look. Finding a way to do this came about through a lot of practical research and experimentation, and crucially through looking at the work of other photographers to identify what I was attracted to or what made me think and why it did so. The way that the photograph can transform the way we see and understand things became a crucial part of the contextual research that informed the early development of my work. I had always admired the photographs of Edward Weston and Irving Penn, and the way that a simple pepper or a discarded cigarette could become something sensuous or sublime held a great fascination for me.

From the series: SOUP: 135°–155° W 35°–45°N. SOUP: Ruinous Remembrance.

Ingredients; plastic flowers, leaves, stems and fishing line. Additives; bones, skulls feathers and fish.

Photography by Mandy Barker, 2011

It was the isolation of the subject that became important, and the idea that if you remove the subject from its context you might see things very differently.

The series Indefinite grew out of the idea of decontextualising and reframing the debris found along the shore. I took the unwashed and unaltered objects back to the studio and, concentrating purely on single objects, carefully lit them against a black background to avoid any unnecessary distraction within the image. The enveloping black space became a metaphor to evoke a sense of the deep sea and the objects became strange sea creatures emerging from the deep ocean. The paradox of transforming a discarded and harmful object into something aesthetically interesting became an important characteristic of the work, something that might hook people in and introduce them to this vast global problem.

However, it needed something else, something that would convey a message about pollution in the marine environment, something that would provide information about the detrimental effect that this plastics debris has. Text was an obvious choice, but I needed to create a balance between drawing people in to the images through the visual qualities and form of the photograph, and then hitting them with the scientific facts and the dangerous nature of these seemingly beautiful objects. I remembered coming across the work of Cornelia Parker, who had created a photogram of a single feather, and the first impression was of a simple yet stunningly beautiful image. But alongside the image text added another interesting dimension. The text stated that this feather had been to the top of Everest and that just brought so many different questions to my mind—How did it get to the top of Everest? Did she take it? It was the fact that I wasn’t just looking anymore, but I was thinking, and it was the text that had altered my experience and understanding of the image. It was not that the image illustrated the text or that the text described what was seen, but that together they created something far more engaging and opened my mind up to other possibilities, and that individual connection made it personally relevant.

Another key influence was Simon Norfolk. He had made a series called The Hebrides: A slight disturbance in the sea. The work was concerned with military activities in this remote and beautiful part of the world. I remember one image of a tranquil sea at sunrise. It was a seemingly straightforward and again beautiful image, but the caption revealed that a nuclear submarine had accidentally sunk a fishing trawler here and drowned the fishermen working on it, and this information was very unsettling and destabilising.

The way the addition of text can change the way we understand what we are looking at became a fundamental aspect of my working method for this series, and has continued subsequently in all my work. I feel that short captions that get straight to the point in a few words can be far more compelling than a whole paragraph written about an issue. The text I eventually used for Indefinite states simply the number of years it takes each plastic material to decompose in the sea. These simple statements juxtaposed with images of different types of plastic, presented a narrative in time culminating with an image of a piece of polystyrene, which stays in the seas indefinitely and gives the series its title. In addition, at the end of the series I provided a thumbnail of each image with statistical information about the particular type of plastic in the photograph.

Getting ideas or vague thoughts I have for images out of my head and onto paper is something that I have always done, as I feel it makes it easier to see how I am thinking about things. I record all my ideas and activities in journals, a process I describe as thinking out loud, which forms a key role in my research strategy. It enables me to reflect and allows me to see how different aspects of my research connect and very often how elements that I may have initially put to one side become relevant again or take on new meaning. It is a process that fuels my imagination and keeps my ideas moving forward, which is imperative in terms of artistic growth.

When I actually get down to constructing the images I may have to change things, for example, compositionally to make the image work. The way the sea currents bring different elements together in the ocean is unpredictable, so the working methods I adopt need to reflect that randomness. The sketches I make enable me to think in broad terms about an idea, but it might look very different when it comes to creating the work, and so I keep an open mind and am happy for chance to play a part. For example, in laying out a range of elements to photograph I noticed the word ‘sea’ written on the end of a commercial plastic bag, and the word ‘hazardous’ that had come from the side of an inflammable oil carton, and also the word ‘waste’. All of which had come together quite accidentally but became an essential part of the work.

The more research I carry out about plastic debris in the oceans the more it feeds my imagination and my determination to try and raise awareness through my work. Having become familiar with the various organisations that research and campaign about the issues of plastic in the sea, and identifying and speaking with the scientists and environmentalists who study the movement of plastics across the world’s oceans, I became aware of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. This is the name given to the mass accumulation of plastics in the North Pacific Ocean and has been described as ‘plastic soup’. Due to the sheer scale of this problem and the way that waves and the light reflects and distorts, it is impossible to represent this phenomenon accurately or in detail in situ. Constructing images that represent what is out in the oceans is the only way to achieve the desired results.

The starting point for this new work was to create something that related to the depth and extensiveness of the way that the ocean currents bring together plastics on such a vast scale. I made many practical experiments initially using a large format studio camera and film and trying many different ways of floating plastics on water, hanging pieces of debris from fishing wires and using layers of glass. But it just wasn’t possible to achieve the depth or scale necessary to duplicate the random way that plastics come together in the sea and create the feeling of floating rather than being static in one fixed position.

One of the main influences, which led me to think about how I could tackle the problem, came again from my contextual research and in particular the work of Andreas Gursky. Gursky’s work tackles issues around consumerism, which has resonances for me, and the way he manipulates foreground, middle ground and background in linear layers was

Marine Debris balloons collected from around the world. Ingredients: Silver Wedding Anniversary, Now I am 3, Age 5, 60, plain: red, blue, yellow, green, pink, orange, silver, white, Ruby Wedding, It’s a Girl, Thomas the Tank Engine, Barclays, ghost face, unidentified motifs ×15, balloon stick, balloon inflation stoppers, Happy Birthday, Happy Retirement, Happy Birthday, Happy Meal, HAPPY?

Photography by Mandy Barker, 2012.

something that I found interesting and valuable, and this fed into the way I began to approach my work. Digital technologies gave me much more control in terms of the kinds of images I could make. For example, through montage I could combine different images together rather than trying to create something in one single image.

It was also important to me that the plastics I photographed were salvaged from beaches around the world, to replicate the way that plastics become dispersed naturally through the oceans’ currents. For example, the oceanographer Curtis Ebbesmeyer sent me four samples of children’s bath toys from Alaska. The toys had gone into the sea off the coast of Hong Kong following a container spill in 1992. Ebbesmeyer’s research showed that these toys had been in the sea for sixteen years, having been around the North Pacific Gyre1 three times since the original spillage before finally being deposited and becoming frozen in ice on the shoreline of Alaska.

Following a similar principle of captioning my earlier work, each of the new composite images was given the main title of SOUP, with a sub-title that detailed the particular subject of the image, such as Turtles or Fragmented Cups. But this time, inspired by the ‘plastic soup’ description, I added a list of ingredients, which I felt was important in providing the viewer with the facts of what exists in the sea, and the disturbing reality that plastics can travel anywhere the current will take them.

The connections built up through my research led to an invitation by Dr Marcus Eriksen of the 5GYRES marine research organisation, and the Algalita Marine Research Foundation in the USA to join an expedition. These are two non-profit groups that campaign against plastic pollution and had organised an expedition to sail through the Japanese tsunami debris field. In March 2011 the most powerful earthquake to hit Japan triggered a major tsunami causing destruction along the Pacific coastline of Japan’s northern islands. The month-long expedition from Japan to Hawaii was made possible for me through an environmental bursary from the Royal Photographic Society, which was a competitive process and I had written a proposal for consideration; it was a life-changing experience for me and a privilege to work alongside an international crew with different specialisms. But most importantly I was able to see firsthand exactly what plastics look like in the sea, and as a primary source of information this became significant to the way I responded creatively.

Being connected to the reality of the devastation that I witnessed firsthand in Japan before the voyage shifted my perspective. Staring down into the ocean and seeing unmistakable objects pass by such as a laced boot or a pair of children’s shoes, cups, caps and a coat hanger, was a constant reminder of the lives lost to this natural disaster, and it changed the way I began to think about the kind of work I could make. I began to see similarities in the plastics collected;

‘EVERY … snowflake is different’

Ingredients: white marine plastic debris collected in two single visits to the shoreline at Spurn Point Nature Reserve England 2011. Includes added shards from other countries. (Snow flurry ingredients; draught piece, padlock, industrial mask, bread tie, cake decoration pillar, paracetamol packaging, plunger, fire alarm casing, aerosol nozzle, egg holder …

Photography by Mandy Barker, 2011.

a shred of bag that looked like a face or a piece of Styrofoam that looked like a bone.

33.15N, 151.15E. From the series: SHOAL.

Included with trawl: tatami mat, part of the floor of a Japanese home, fishing related plastics; buoys, nylon rope, buckets, fish trays, polystyrene floats shampoo bottle, caps, balloon with holder and petrol container.

Photography by Mandy Barker, 2012.

Because of the demands of their disciplines scientists have to remain detached and there is no room in scientific study for personal responses to the subject. I feel it’s important for artists to be involved with issues such as this as art can connect with people in different ways and offer a new perspective. The series SHOAL was developed from trawls and net samples at various points on the voyage between Japan and Hawaii, and also from the tsunami-affected shoreline in Fukushima Prefecture. Each image included a different trawl sample and is captioned with the grid reference of where each sample was collected, a marker to pinpoint a specific location.

Recently, I visited Hong Kong to speak at the inaugural conference for a charity called Plastic Free Seas. I was shocked by the statistics and to discover that over 50 tonnes of polystyrene was going into landfill in Hong Kong everyday just from takeaway cartons, and the beaches are piled high with it. I visited some of the beaches and was taken to one of the islands that is particularly affected and I collected samples and photographed the debris. This led to the creation of a new project specifically about Hong Kong.

I wanted to create an opportunity to connect the people of Hong Kong with the problem of plastic pollution, and therefore included elements in the design of the images that would be of specific cultural relevance. For example, in 2012 they had a container spill of plastic pellets or nurdles,2 and that’s one image. There are also plastic lotus flowers, which are linked to notions of beauty in Hong Kong. Tea packaging was another key element and a cigarette lighter with an image of a panda, the national animal of China, printed on the side. The final series Hong Kong Soup was nominated in the WYNG Masters Award3 and was series winner in the Lens Culture EARTH Awards.4 But I would never have thought about doing that if those links that my research had created hadn’t added another dimension to my thinking about waste in different parts of the world.

Keeping my work fresh is something that I need to be aware of if I am to connect more people to the problems of marine pollution. This means that as part of my research process I have to think and plan ahead, so being alert to the possibilities and looking for potential new ideas is an essential activity. 2014 was the year of the football World Cup and this became the catalyst for the series Penalty. Rather than concentrating on different types of plastic I decided to focus attention on one single plastic object, the football, as a global symbol and one that would potentially reach a global audience. I put a call out via social media for people to collect and post footballs or pieces of footballs that had washed ashore on beaches around the world; and I have to say I was surprised by the response.

Lotus Garden. From the series: Hong Kong Soup: 1826.

A collection of different species of discarded artificial flowers (that would not exist at the same flowering time in nature) should not be found in the ocean. The flowers were recovered from various beaches in Hong Kong over the past three years (includes; lotus flowers, leaves and petals, peony, carnation, rose, blossom, holly, ferns, castor and ivy leaves).

Photography by Mandy Barker, 2014.

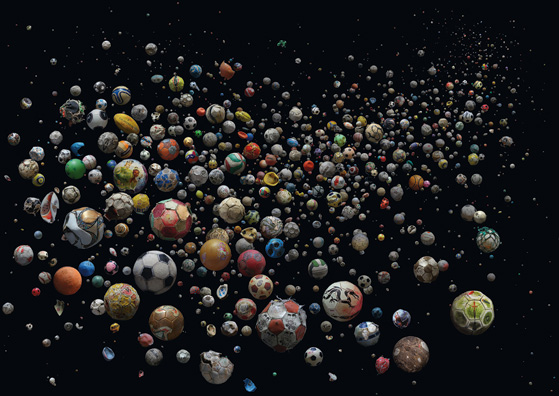

The World. From the series: Penalty.

Photography by Mandy Barker, 2014.

In total, 89 members of the public collected 769 footballs and pieces of footballs, with the addition of more than 223 other types of balls from 41 different countries and islands and 144 different beaches in just 4 months. The recovered footballs were incorporated into a series of 4 images—The World, Europe, United Kingdom and One Person. The Guardian newspaper in the UK did a double page spread for their ‘Eyewitness’ section and there were several other publications around the world that covered the story, along with interviews with CNN in the USA. So, the idea really took off and found the global audience I set out to reach.

The project that I am working on at the moment takes the idea of plastic pollution in the sea to a different level. I was Artist-in-Residence in Cork, Ireland recently and worked with a researcher from the University of Cork looking into micro-plastics. At the time laboratory studies at Plymouth University had found plastics in plankton and very recently new research was published5 revealing that studies have found that plankton are ingesting plastic in the natural environment. Plankton represents the bottom of the food chain and ultimately this will have consequences for us all.

I see my role as an interpreter, to be aware of the facts about the harmful effects of marine plastics and to understand the science and to present it in an accessible way through my work and help to connect this global problem to a wider audience and hopefully in some way change things for the better.

Interview by Mike Simmons

Notes

1 The term gyre refers to a large system of rotating currents in the ocean and there are five major gyres across the globe. In the North Pacific, South Pacific, the South Atlantic, the North Atlantic and the Indian Ocean.

2 Nurdles is the term given to small (microplastic) resin pellets usually between 1 and 5 cm in diameter that form the raw manufacturing material for a range of plastic products.

3 The WYNG Masters is a non-profit photography initiative designed to stimulate the development of photography as an art form in Hong Kong and seeks to create awareness on different themes of social importance for Hong Kong. The award encourages proposals internationally and offers substantial cash prizes. More details can be found at: www.wyngmastersaward.hk/index.php/en/master-about-en/commission-en.

4 The LensCulture EARTH Award is an annual international photography competition whose theme is the natural world and how we live on our planet. More information can be found here: www.lensculture.com/earth-awards-2015.

5 The paper Ingestion of Microplastics by Zooplankton in the Northeast Pacific Ocean by Jean-Pierre W. Desforges, Moira Galbraith and Peter S. Ross is published in the Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, Volume 69: Issue 3. October 2015. Available from Springer Link: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00244–015–0172–5#/page-2.