1The Core Elements of Rhetorical Theory

Before going further, it is important to outline the core elements of the contemporary theory of rhetoric and to lay the terminological foundations for the rest of this work. Such fundamental considerations are necessary because the academic study of persuasive communication spans a variety of scholarly disciplines today, each with its own set of research perspectives and terminological lexica.11 As a discipline, rhetoric has largely become a “victim of modern academic differentiation,” and modern rhetorical theory building has been limited to a few influential twentieth century thinkers.12 Such fragmentation has led to a myriad of “rhetorical” concepts, theories, and terminology in adjacent fields, and recent studies have illustrated a number of fallacies regarding the use of the word rhetoric by communications researchers across the globe.13 As a result “the English word rhetoric […] is in no way a rigorous scientific terminus; it is an informal plastic word that can be used to designate just about anything that has to do with language or communication.” Further: “if we want to drag this word out of the colloquial and establish it as a legitimate academic term, then it must refer to something specific.”14 In short, “general rhetoric must now reestablish its position within current systems of knowledge.”15

In addition to a lack of terminological clarity and theoretical focus in the academic world, there is a broad misunderstanding of rhetoric in non-academic circles as well. In general, the word rhetoric in the English language has explicitly negative connotations, often associated with manipulative communication, or as “language that is intended to influence people and that may not be honest or reasonable.”16 The misconception of rhetoric as manipulation is particularly damaging in light of the fact that some rhetorical theorists see

rhetoric as fundamentally different from manipulation. Those who manipulate, we can say, have secret goals, do not act openly, and communicate using tricks. Such communicative action must be excluded from real rhetoric, which is by definition always tied to socially acceptable means.17

While a discussion the origins of this lay conception and its perpetuation in journalistic and popular discourse are outside of the scope of this work, it is important for rhetoric as a scholarly discipline to combat such negative stereotypes and fundamental misunderstandings. Only by rehabilitating the term rhetoric as a colloquial curse word can the academic field of contemporary rhetoric be taken seriously in public and scholarly discourse.

To follow Stefanie Luppold’s suggestion, “in light of the unmanageable variety of conceptions of rhetoric and the associated definitions of rhetoric that have emerged, it seems appropriate to briefly clarify here what is meant by the term rhetoric as an academic discipline.”18 Put briefly, rhetoric is the study and art of persuasive and strategic communication in real-world contexts. This focus was established in ancient antiquity, with foundational works by Plato, Aristotle, Cicero, and Quintilian all focusing on persuasion as the core concern of rhetorical investigation and rhetorical theory.19 Although some may question the utility of integrating such sources directly into the foundation of a modern science, many elements of these ancient theories continue to be applicable to a contemporary theory of rhetoric.20 By defining rhetorical communication as explicitly strategic, contemporary rhetorical theory can confine its analytical focus to cases of intentional and planned communication. From this perspective, there is no such thing as accidental or coincidental rhetoric, and such instances in which unintentional or unplanned communication leads to accidental opinion change do not count as rhetorical.21 As such, contemporary

rhetorical theory excludes a wide array of communicative phenomena that do not meet the requirements of a rhetorical object of investigation […] Rhetoric is to be understood as a social model of interaction in which human actors act in a particular way: they are persuasive. Thus, the rhetorical case comes into existence when one person seeks to persuade another person.22

While the concept and methods of persuasion have become the focus of research in a wide variety of other academic fields, for the purposes of this work, “to persuade someone means to change either their opinion or their attitude: to cause a [voluntary] change from mental position A to a new mental position B.”23 This conception corresponds to the common understanding of persuasion as “changing someone’s mind” (as in from pro to con), but also includes the strengthening or weakening of someone’s opinions or attitudes (as in making someone more strongly or weakly pro or con).

In some cases, persuasion takes place at the moment of performance, as when one person convinces another to agree to a project with an effective presentation. And for the most part, rhetorical theory has focused on producing persuasive communication for individual situations and contexts. Both research and experience have shown, however, that changing a person’s behavior (and above all sustaining such behavior) often takes time and repeated acts of persuasive communication. In this sense, rhetorical communication sets processes of persuasion in motion, or seeks to augment or curtail processes that are already in motion in a given audience.24 This “processuality” of persuasion “surpasses the perspective of the mere situatively limited act of persuasion.” Instead it requires “a persuasive process calculus” that moves away from “the classical, punctually conceived act of one-time persuasion.”25 Whether in advertising campaigns or in politics, a significant portion of strategic communication in public discourse today is the result of a coordinated effort that unfolds over time. As political communications scholar Jarol Manheim has described it:

Given that change is a longitudinal phenomenon […] campaigns must comprise progressions of messages, message effects, and observed changes of the target. They are, then, inherently sequential. It is the case that, on rare occasions, singular events can alter the psychological states or behaviors […] But it does not follow that singular, purposeful bursts of information per se […] can have the same effect.26

As a result, persuasive campaigns

are more or less long-running aggregations of messages […] It is both unduly limiting and counter-productive to think exclusively in terms of more or less singular messages that are delivered under more or less isolated circumstances […] Rather the strategist should think of the campaign as a long-, or at least longer-, running series of opportunities to […] generate the desired movement.27

This longitudinal perspective is critical for the contemporary theory of rhetoric to be able to deal with complex cases in the real-world of political and social discourse. In such cases, the rhetorical strategies planned and translated into texts by communicators lead to longitudinal persuasive (and thus rhetorical) processes that are set in motion both by single events and as the result of coordinated campaigns over time. More explicitly, successful rhetorical strategies trigger rhetorical processes in target audiences. These two theoretical categories are directly connected to one another through the category of text, and all three are important elements of the contemporary theory of rhetoric. In the chapters to come, each of these categories will be used to describe specific aspects of the phenomenon of polarization from a rhetorical perspective. Polarizing strategies refer to the conception, planning, and execution of (both punctual and longitudinal) communication designed to polarize, polarizing texts incorporate specific elements and structures associated with the strategy of polarization, and polarizing processes refer to the effects of such texts on audiences, both in the moment and over time.

To briefly summarize, “in practice, rhetoric is the mastery of success-oriented, strategic processes of communication.”28 In order to successfully use communication to reach their real-world goals, a speaker must determine what they want to persuade their audience of and must then formulate an appropriate text that delivers their persuasive message to their audience.29 Accordingly, both ancient and modern rhetorical theories have focused on three core theoretical categories: the orator (a strategically acting communicator), the text (as the communicative product of the orator), and the context (divided into the situation within which communication takes place and the audience as the target of persuasion). Each of these categories represents an important object of investigation for contemporary rhetorical analysis and an important point of consideration for any would-be persuasively acting individual. For this reason, and to better lay the foundation for the work to come, the following section will briefly discuss each of these three core elements from the perspective of contemporary rhetorical theory.

1.1Orator

In comparison to other scholarly fields that deal with human communication, rhetoric places the strategically active speaker (orator) at the center of its theoretical and analytical focus. Ancient rhetorical theorists ranging from Aristotle to Quintilian and Cicero focused their works on the artifex as an “expert” or “specialist” in the rhetorical arts: how such a person should be defined and how they can act most effectively and morally.30 More recently—and using Shannon and Weaver’s linear model of communication as a starting point—Joachim Knape has asserted that rhetoric

has only one main concern from which everything else is derived: how can the “sender,” which we name the “orator,” strategically and effectively communicate to meet life world goals? This fixed perspective gives all other theoretical considerations a focused direction. We see communication sub specie oratoris, that is to say: completely from the perspective of the orator.31

As briefly mentioned above, in order to act rhetorically (that is, to assume the role of an orator), a speaker must plan and undertake a number of actions. One of the most important is to clearly analyze their real-world goals and explicitly identify how persuasive communication can help them reach their aims. Whether a person wants to sell a product, get elected to public office, or receive a promotion in their workplace, they need others to act in a certain way that is beneficial to their cause. Once a speaker has clearly identified what they want to achieve, they can then begin making mental calculations about what persuasive communication and arguments might most effectively move their audience to do what they need. Should the salesperson highlight the quality of their product, or its low cost? Should the politician make campaign promises to a target constituency, or attack their opponent’s positions? Should the employee undertake direct negotiations with their superior, attempt to secure a letter of reference from a respected coworker, or write a list of successful projects they have completed for the organization?

These questions highlight the central concept of oratorical calculation in rhetorical theory. People acting rhetorically do not seek to persuade others just for fun or for mere exercise; they seek to use their persuasive communication to effect real changes in the real world. As described by E.E. White: “When we see that a situation exists that can or should be modified by communication […] we may respond to it by using symbols in hope of inducing changes in readers/listeners and thereby altering […] the provoking circumstances.”32 In order to meet their real-world goals, rhetorical actors must induce others to act in a specific way. Not only must an orator clearly identify their own goals, they must also strategically assess a wide variety of situational and psychological factors in the communicative instance, and must successfully integrate such assessments into an appropriately formulated text. Within this context, a person seeking to act persuasively must generate a specific plan of action in order to achieve the desired effects in their audience. Such planning results in a rhetorical strategy, according to which they can formulate their communication:

Rhetorical strategies are success oriented, anticipatory plans of action. They are driven by an overarching goal-instrument calculus (Ziel-Mittel-Kalkül) on the part of an orator: certain rhetorical instruments are purposefully selected for communicative use within a concrete setting, because the orator judges them to have a certain potential for influence that seems conducive to their concrete persuasive goals.33

By implementing an appropriate rhetorical strategy, speakers hope to maximize their chances of successful persuasion and to ensure that the effects of such persuasion actually help them meet their real-world goals.

Both ancient and modern theories of rhetoric sought to systematize such oratorical strategizing so that orators could hone their skills at situational assessment and appropriate text formulation. One recent model breaks down the concept of orator into three functional roles that each orator takes in the formulation of their persuasive text: the concepter, the texter, and the performer.34 During conceptual work, the orator acts as a “strategic guide that provides the plan for further text-production and text-emission processes […] The result of a concepter’s work is the strategic masterplan that serves as the guideline for all further stages of production.”35 After conception, the orator shifts roles, becoming “a semiotic Artifex, a craftsman, tool maker, or weaponsmith” who produces a concrete text that successfully integrates the goals and arguments formulated during conception and that is appropriate for the communicative context within which the text will be presented to the target audience.36 Finally, the orator assumes the role of performer, who “has the task of making the coded text [created by] the texter communicatively available for the addressee.”37 In short, the orator shifts from tool maker to tool user, from military commander and weaponsmith to swordsman.

While rhetorical theory has largely conceived of the orator as a single persuasively acting individual, contemporary rhetoric should be able to take a broader view. Situations in which multiple individuals work in tandem to formulate and create persuasive communication require the theoretical category of orator to be expanded. As Luppold notes regarding the threefold model of oratorical roles, “in certain cases with complex actors, these roles can be fulfilled by different persons or groups of people.”38 Indeed, when considering organized, hierarchical groups such as marketing agencies, political campaigns, or mass media outlets, it is clear that the oratorical roles of conception, text formulation, and performance are indeed divided among different individuals and groups. Still, because of the clearly planned and highly coordinated nature of production, we often discuss such communication as coming from a single institutional author. In such situations, contemporary “rhetorical theory cannot avoid dealing with the question of corporate or institutional authorship (institutions or groups that to a certain extent, speak ‘with one voice’ in advertisements, public relations, etc.).”39

In this sense, the concept of the orator refers to “an abstract entity that is analytically derived from the study of myriad discourses and can be observed from different perspectives: as a cognitive calculation, a social role of action, or as a factor of communication and text constructing entity.”40 With regards to institutional authorship, the “collective” strategically communicating actor comprises what is called an orator complex: a group of individuals working together within an organizational structure with a common goal of crafting and delivering a persuasive message to a given audience. The rhetorical analysis of such orator complexes must also include a description of the relationships between, and the productive tasks assigned to, individual actors within a structured institutional hierarchy.

In his 2011 book Strategy in Information and Influence Campaigns, Jarol B. Manheim deals almost exclusively with the persuasive efforts of institutional orator complexes. He begins his work defining such campaigns as “a systematic, sequential, and multifaceted effort by one actor to inform, or to influence the perceptions, preferences, or actions of, some other actor or actors.”41 And although he clearly views communication from the perspective of a strategically acting communicator (who he ultimately names the protagonist), he devotes little space to detailing the necessary level of organizational coordination in the complex entities he has in mind (examples include “governments, international organizations, labor unions, nongovernmental advocacy organizations, corporations or even insurgent groups […]”).42

The vagueness of Manheim’s protagonist mirrors a theoretical problem for the concept of the orator complex as an analytical unit in rhetorical theory: how coordinated does an organization or group have to be in order to be legitimately described as an orator complex? Indeed, the idea of an orator complex immediately raises questions of organizational hierarchies, production processes, and problems of collective action and responsibility. If one department within a company initiates a campaign, is it legitimate to call the entire company the protagonist (or designate it as an orator complex)? If a relatively unorganized group of protesters comes together to chant slogans at a demonstration, can they be called an orator complex?43 Particularly when it comes to more diffuse groups such as political parties and social movements (such as the tea party), what constitutes an orator complex can be difficult to clearly define, and the borders between different orator complexes can quickly become blurred. The situation becomes even more complicated when different orator complexes seek to influence one another as part of a broad political campaign.

Manheim recognizes some of the difficulties in defining what constitutes a protagonist and a campaign, and points to the presence of a shared strategy as the underlying factor that unifies individuals and institutional actors:

It is through the medium of strategy that we will bring together the diversity of campaign decisions, actions, applications, and outcomes into a single, more or less unified argument […] In general, a campaign strategy is an overarching directional framework for action, a concept or idea that integrates the many diverse parts of the campaign into a more or less unified whole.44

This description inverts the classical relationship between orator and strategy: instead of viewing a rhetorical strategy as the mental product of a single orator, the strategy itself becomes the unifying glue that binds disparate individual actors into a coherently acting protagonist.

This idea of a unifying strategy explicitly draws on work by Kenneth Burke and a field known as ‘constitutive’ rhetoric that helpfully reframes the category of orator as a sociological entity. In developing his theory of rhetoric, Burke sought to refocus the discipline around concepts of identification and consubstantiation. As he famously wrote in A Rhetoric of Motives, “You persuade a man only insofar as you can talk his language by speech, gesture, tonality, order, image, attitude, idea, identifying your ways with his.”45 In this formulation, orators must generate identification with their audiences so that they become “identificationtial” with the speaker, and thus become open to changing their opinions and attitudes in the orator’s chosen direction.46 In this sense, orators are restricted in their persuasive action by the social setting they find themselves in: “true, the rhetorician may have to change the audience’s opinion in one respect; but he can succeed only insofar as he yields to that audience’s opinions in other respects.”47

For an orator to successfully generate “consubstantiation”, he must use his communication to create a common narrative identity with his audience. Towards the end of the 20th century, some scholars of rhetoric began to focus on the ways in which such oratory “constituted” a new shared group identity between the audience and the speaker. As James Boyd White wrote about this new conception in 1985:

But ‘rhetoric’ also needs definition, and I think it should be seen not as a failed science, nor as an ignoble art of persuasion (as it often is) but as the central art by which culture and community are established, maintained, and transformed. This kind of rhetoric—I call it ‘constitutive rhetoric’.48

Further,

The study of this process—of constitutive rhetoric—is the study of the ways we constitute ourselves as individuals, as communities, as cultures, whenever we speak.49

[...]

The rhetorician, like the lawyer, is thus engaged in a process of meaning-making and community building of which he or she is part of the subject.50

This idea quickly gained popularity, and scholars began focusing on the identity forming and community building functions of oratory, especially with regards to socio-political movements around the globe.51 Jarol Manheim’s conception of information and influence campaigns—and of his protagonist—are directly derived from such research. 52

By adapting work on the generation of group identity through the shared use of rhetorical strategies, contemporary rhetorical theory can legitimately consider larger and less-coordinated groups as a certain kind of oratorical unit. In a recent analysis of U.S. Senate rhetoric, for instance, Angela McGowan asserted that “constitutive rhetoric creates a collective identity,” and that “constitutive rhetoric helped senators create a collective identity that reconstituted a people,” who “became part of a collective ‘we’ that emerged as a bipartisan group.”53 According to this ‘constitutive’ conception, the category of orator can be conceived of as a group of individuals who utilize common rhetorical strategies and narratives to generate and reinforce a common identity.

Clearly, a constitutive conception of the orator has its own methodological problems: in practice, the heuristic category of “common rhetorical strategies and narratives” may be too general to clearly define a loose affiliation of individuals or institutions as a cohesive rhetorical unit. Still, such an understanding is helpful for the rhetorical analysis of real-world political discourse, particularly as it relates to the highly complex dynamics of information and influence campaigns. By focusing on shared strategies, rhetoricians can analyze situations in which individual actors and institutions do not explicitly coordinate their communication but can still be considered to act as a part of a coherent social movement or group.54

This is best illustrated by a brief example. To use a case that will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 2, consider the environmental movement, which consists of a broad patchwork of different organizations, individuals, and institutions. While it is relatively easy to imagine a single organization as possessing the hierarchical consistency to constitute an orator complex, the idea of highly coordinated and hierarchical decision-making structures among all of the disparate groups involved in the environmental movement is clearly implausible. Although some elements of the movement certainly coordinate their persuasive messaging, others do not, and some actors (organizations, individuals) utilize similar rhetorical strategies (and have similar real-world goals) but would not label themselves as part of the “movement.” Whereas classical rhetorical theory can deal with persuasively acting individuals within the movement, and a more modern rhetorical theory might be able to analyze coordinated institutions as orator complexes within the environmental movement, a constitutive rhetorical conception of the orator can legitimately analyze the rhetoric of the broader environmental movement by focusing on the shared rhetorical strategies employed by a range of individuals and institutions, even those who do not explicitly identify themselves as a part of the movement.

Manheim’s network-based concept of campaigns can be integrated into existing rhetorical theory to address this problem. As he describes it,

while there can certainly be isolated actors and actions within the context of a given campaign, the essential structural form and dynamic is the social network—a connection of inter-connected and/or interacting participants through which […] the protagonist seeks to exercise influence upon the target.55

Manheim asserts that a primary task for the planning or the analysis of a given persuasive campaign is to map out the network of stakeholders and communicators involved by identifying the “nodes—the individuals, groups, organizations or institutions that are members of a given network—and links—the exchanges of money, personnel, programs, and other resources or activities that flow between or among the nodes.”56

In situations such as the environmental movement (or the tea party movement), it is thus more appropriate to speak of an oratorical network: a loose affiliation of individual orators and orator complexes that mirror and match each other’s rhetorical strategies to constitute a broader and less coordinated oratorical unit than an orator complex. Within this framework, the nodes of an oratorical network are specific orators or orator complexes that serve different roles and have distinct agendas within the broader campaign, while the links designate the flow of parallel rhetorical strategies and textual elements between nodes. By mapping an oratorical network, modern rhetorical analysis can identify and isolate the various orators and orator complexes that make up a given social movement or campaign, can separately analyze each individual node’s use of a shared rhetorical strategy, and can describe the links between each node as the mirroring and matching of strategies and textual structures among different orators in the network.

Chapter 3 will illustrate the practical usefulness of this theoretical concept. More specifically, the analysis of polarizing strategies in tea party communication will explicitly map out textual and strategic links between four primary nodes in the tea party network by tracing the use and dissemination of a specific polarizing framework: the “makers” vs. the “takers”. The case study will illustrate how each node in the network pursued polarizing strategies for their own independent reasons and how the parallel and mirrored use of polarizing strategies and texts helped constitute the tea party movement as a coherent and analyzable oratorical network.

1.2Text

If the strategically acting orator is the “Archimedean point” of rhetorical theory, the text is both the product of their strategic calculations and the tool they use to persuade their audience.57 As Luppold has described it, “the communicated text stands at the interface of two mental systems and their operations: on one side is the mental system of the text producing and text emitting orator, on the other side the mental system of the text receiving and re-acting addressee.”58 Because persuasion depends on well-considered and well-formulated texts, a central focus of rhetorical theory since antiquity has been to instruct potential orators how to translate their goals and persuasive message into an effective text. Indeed, from Aristotle’s consideration of rhetorical genres and detailed discussion of rhetorical topoi in “The Art of Rhetoric” to the systematized exercises devoted to text formulation in Quintilian’s “Institutio Oratoria,” classical rhetorical theory focused on “the study of the rules and principles of text formulation.”59 This led to the development of an organized model of text production known as the officia oratoris, which represented a strategic roadmap for ancient orators to generate persuasive texts and effectively deliver them to audiences.60

In addition to formalizing production strategies, ancient rhetoricians also devoted significant efforts to detailing both simple and complex textual structures that could be used as building blocks to formulate persuasive texts for audiences. The categorization and description of compositional elements such as rhetorical figures, tropes, loci, and stylistics played a major role in ancient theory. Such elements provided orators with a set of functional tools that could be used as needed to assemble a “good text” (bona oratio). This focus gave rise to a conception of rhetoric as an ars bene dicendi—as “the art of good speech”—which dominated rhetorical study throughout the middle ages and heavily influenced modern academic and lay conceptions of the field. As Knape wrote:

Over time, rhetoric has come to be seen more and more as purely a theory of text formulation (elocutio) combined with a set of stylistic devices and instructions for the construction of phrases (compositio). This trend has led to a well-known stereotype: that rhetoric is nothing but empty wordplay.61

The twentieth century brought broad diversification in the number of academic fields devoted to communication and textual studies. Academic fields such as linguistics, philosophy of language, literary studies, media studies, and social and cognitive psychology all have their own perspectives on communication, the connections between mental processes and text production, and the effects of specific textual structures on receiver (audience) mental processes. On the one hand, this has led to terminological and theoretical fragmentation; as Robert Craig puts it, “except within these little groups, communications theorists apparently neither agree nor disagree about much of anything.”62 On the other, this diversity of research has produced many insights that have been helpful in updating ancient systems of text production for a modern theory of rhetoric. In particular, the fields of text linguistics and pragmatic speech act theory have provided useful frameworks and insights for a more modern conception of persuasive texts, and the connections between mental goal setting, texts, and their reception by specific audiences.63 Twentieth century theoreticians such as Burke, Genette, Perelman, and de Man all integrated concepts of textuality from other disciplines into their discussions of text while simultaneously adapting ancient ideas and structures for a modern age.64

As previously discussed, the contemporary theory of rhetoric shifts its focus away from an ars bene dicendi and toward persuasive communication (ars persuadendi). While the study of figural structures and compositional elements in specific texts remains an important part of rhetorical analysis, “these figural structures are only interesting […] when they are activated (functionalized) in actual rhetorical cases; that is when they are integrated into acts of persuasive communication.”65 For this reason, much current rhetorical research focuses on the connections between mental rhetorical strategies, specific communicative settings, and concrete figural and argumentative structures to achieve a real-world goal. As Knape has put it, “textual rhetoric concerns itself with one main question: how do the communicative intentions of an orator become text?”66

Despite significant interdisciplinary debate about the definition of a text, in this work a text is considered a “bounded, ordered, complex of signs arranged with communicative intention,” and a “concretely coded structure for communicative use.”67 It is important to note that although a text is concrete in terms of its codality and its arrangement, it is also understood as an “abstraction beyond and independent of any form of medialization.”68 To put it another way, a text emerges once an author has arranged (linguistic) symbols in such a way as to create an understandable sentence, paragraph, or work.69 The medialization of a given text can take on many different forms, and occurs after the process of text formulation. An example provided by Knape vividly illustrates this division:

Let us imagine an advertising agency that is to organize an ad campaign for a brewery. First, the “copywriter” department is activated […] and they come up with the one sentence text, “The King of Beers” […] This text might land in the media department, which then considers how best to medialize this text, whether on coasters, on t-shirts, on billboards, on neckties, on the radio, or on television […] The text is always the same, but the media change.70

In this sense, contemporary rhetoric locates the concept of medium at a different theoretical level than text: a medium is considered “a device used to save and send texts,” and “a platform on which [they] can be displayed, but the text exists at a semiotic level and thus at the higher level of information.”71

This division between text and medium is critical for a contemporary theory of rhetoric to disciplinarily differentiate itself from newer but related fields such as media studies. While rhetorical considerations of medial effects and constraints on texts constitute an interesting and important sub-discipline (media rhetoric), the core focus of rhetorical theory remains on the generation and analysis of persuasive texts, regardless of the medium on which they are saved and presented. This is not to say that the potential persuasive effects of media cannot and should not be a part of rhetorical strategizing and planning; such considerations represent an important paratextual stage of production. To use Knape’s example, the copywriters focus their efforts on coming up with the most persuasive slogan possible before deciding the best vector to deliver their message to their audience(s).

From the perspective of textual analysis, the persuasive message clearly resides in the text. This broadens the range of potential analytical objects to any number of media: as long as a coherent text can be identified and analyzed, the medium on which it is presented (and analytical considerations of media effects) remains secondary. This is particularly relevant in the context of campaigns that unfold over time and across multiple media types. In such situations, orators and orator complexes construct multiple texts, and may deliver them on multiple different media to multiple audiences over the course of the campaign. As Manheim puts it:

Campaigns typically incorporate messaging schemes that are layered and subdivided, employing variations in timing, distribution channels, near- and long-term objectives, and other characteristics that render them complex rather than simple affairs.72

In such situations, the primary text-analytical goal for rhetoricians is to identify the common and persistent persuasive message encoded in each individual text, and to describe the various production processes and rhetorical strategies behind this message. The analysis to come in Chapter 3, for instance, will focus on the polarizing textual structures and a polarizing framework (the makers vs. takers) that can be found in a wide array of texts generated by tea party orators and orator complexes. Analyzing the consistency of this message across multiple texts will help demonstrate the ways in which the tea party acted as a coherent oratorical network—and how the network utilized polarizing strategies to reach its real-world goals.

1.3Context

If the orator generates rhetorical strategies, and the text is the productive result of these strategies, then the context refers to the situations in which these communicative artifacts come into contact with other individuals and groups. Although the contemporary theory of rhetoric considers texts to be separate and independent from media, it is important to emphasize that no real-world text is ever formulated completely independently from its intended communicative context. Luppold puts it this way:

Naturally it is always possible to extract a text from its original setting as a form of thought experiment, and to plant it into other settings within this mental simulation […] but textual rhetoric is, first and foremost, interested in analyses of texts as communicatively embedded semiotic artifacts.73

Indeed, the context in which a text is both delivered and received is incredibly important to its reception by, and ultimate effect on, an audience. No text is delivered in a vacuum, and no communication “mirrors a modified stimulus-response model of classical behaviorism.”74 Accordingly, “orators face many types of resistance that continually obstruct successful communication. Every element in the communicative realm can become an obstacle that stands in the way of his success.”75 To be successful, an orator must take forms of contextual resistance into account in the strategic planning, production, and delivery of their persuasive texts. And within any given context, a speaker is confronted by resistance in the form of both situational and audience-related factors.

A central normative concept of both classic and modern rhetorical theory is appropriateness (aptum, decorum): the idea that persuasive communication should be calibrated to the specific context in which it will be delivered. In ancient times, this principle was considered a part of the theory of style: as Cicero wrote de Oratore, “it is clear that no single kind of style can be adapted to every cause, or every audience, or every person, or every occasion.” Quintilian, for his part, put it this way:

Since the ornaments of style are varied and manifold and suited for different purposes, they will, unless adapted to the matter and the persons concerned, not merely fail to give our style distinction, but will even destroy its effect and produce an effect quite the reverse of that which our matter should produce.76

Contemporary rhetorical theory considers the dictum of appropriateness important in guiding the entire process of rhetorical production: “the projective calculation that an orator makes with respect to his setting, the addressees, and the instruments is subject to the fundamental rule of practical rhetoric; the postulate of appropriateness (aptum).” A footnote at the end of the quote continues:

To put it another way, an orator must attempt to predict how his addressee will react and which stimuli he can use to most effectively meet his goals. He must also calibrate all of the available factors of communication to match the concrete setting.77

At first glance, this seems obvious: no real-world persuasive text is formulated without at least some knowledge of its intended audience and intended communicative context. But the concept of appropriateness codifies the overarching and guiding principle around which concrete persuasive texts should be formulated. For this reason, is important to provide some detail on the variety of different contextual factors and forms of resistance that an orator may be confronted with and will have to take account of if they are to formulate their texts appropriately. As implied by the preceding quote, the theory of rhetoric generally breaks down the analysis of such communicative contexts into two subcategories: the audience that rhetorical communication seeks to influence, and the setting in which such communication takes place.78

1.3.1 Audience

Because textual interpretation takes place in the minds of others, orators cannot completely control reception. Knape recently summarized the importance of audience considerations as follows:

An orator must have a projective calculation in relation to his audience: he must imagine himself in the psyche of his addressees and formulate his rhetorical strategy tailored to the expectations and needs of his audience members […] Above all, such considerations must focus on the communicative instruments that are most appropriate and effective at influencing a given audience.79

It is important to note here that—much like the concepts of orator and text—the theory of rhetoric considers the concept of audience (or addressee) as both a theoretical construct as well as a concrete element of real-world communicative contexts. To put it another way, when producing persuasive texts, an orator may have in mind a specific person or group of people (the boss, the engineering team) and/or they may also consider broader, more generalized mental models of an audience complex (managers or engineers in general). In Luppold’s words: “Even though there is ‘the real addressee’ […] he is only relevant in the form of existing mental representations in the heads of the orator and the textual analyst.”80 This point is particularly relevant (and more obvious) when applied to rhetorical communication produced within broader persuasive campaigns. It is clear, for instance, that an advertising campaign is formulated to reach a target audience made up of an idealized group of individuals that share certain qualities with one another (e.g., economic status, demographics, product interest), as opposed to specific individuals themselves.

Regardless of whether a text is formulated for specific individuals or a broader (idealized) group, it is critically important for orators to base their strategic calculations on their intended audience (or audiences). This requires orators to have prior knowledge about a range of audience characteristics, opinions, attitudes, and beliefs in order to appropriately calibrate their communication. Over the last century, a wide array of disciplines outside of rhetoric have devoted significant efforts toward researching the myriad factors involved in text reception, and such efforts are incredibly useful for rhetorical theory building. The fact is that, “the field of language reception research is huge. It is an almost impossible task to provide anything close to a comprehensive overview given the limited space available here.”81

Indeed, even listing relevant disciplines themselves proves exhausting, with fields ranging from cognitive science, (social) psychology, linguistics and the philosophy of language, to message effects research, market and advertising research, semiotics, neuropsychology, political science, educational theory and cultural studies—to name but a few.82 Without discounting many others, a few models that have been particularly influential to contemporary rhetoric include Austin and Searle’s speech act theory and the concept of illocutionary acts (including further developments such as those by Bach and Harnish, among many others), Grice’s conversational maxims, Sherif and Hovland’s social judgement theory, and Petty and Cacioppo’s elaboration likelihood model (ELM).83 Chapter 2 will provide more detail on specific models from related fields that are important for a theory of polarizing rhetorical strategies.

For the general theory of rhetoric, a central lesson to be drawn from existing research is that orators must account for three audience related elements: the speaker’s own image (ethos) and authority (auctoritas) with their audience, preexisting audience opinions about the topic, and any specific social or individual factors that might influence the effectiveness of persuasive texts.84 Elsewhere, Kramer has identified five “categories of resistance […] to be anticipated” with regards to an audience: 1) their level of interest toward the topic at hand; 2) their prior knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes toward the topic; 3) intrapersonal factors such as fatigue, aversion to new information, or self-identification with a social group that may be opposed to the topic or speaker; 4) credible and understandable argumentation on the part of the speaker; and 5) appropriateness of speaker performance.85

In the mid-to-late twentieth century, considerations of audience psychological makeup and the conflict-oriented nature of classically defined persuasive processes led Kenneth Burke to develop his concept of identification.86 Kramer describes Burke’s theory as developed “against the backdrop of psychological and anthropological theories, according to which human thought, perception, and action is driven by motive structures, and assumes that persuasion can only be successful by influencing such motive structures.”87 Accoring to Burke, the generation of identification between an orator and his audience plays a central role in persuasion. As he famously put it:

You persuade a man only insofar as you can talk his language by speech, gesture, tonality, order, image, attitude, idea, identifying your ways with his [...] True, the rhetorician may have to change an audience’s opinion in one respect; but he can succeed only insofar as he yields to that audience’s opinions in other respects. Some of their opinions are needed to support the fulcrum by which he would move other opinions.88

Thus, in order for an orator to successfully overcome the potential resistance in their audience, they should adopt (or at least seem to adopt) the characteristics, language, arguments, and even values of those they seek to persuade. Doing so opens audience members to modifying their own positions because the orator becomes both more understandable (linguistically and argumentatively) and more credible (as an assumed member of a shared community). The more an orator is able to credibly identify themselves with their audience (and to get their audience to identify with them), the more persuasive leverage they will have with regards to their chosen topic.

Burke’s theory of identification has also been closely associated with the concept of empathy and “perspective taking” in social psychology, in which “the more sensitivity that a communicator has for the thoughts and feelings of his addressees, the greater the chance of successful communication.”89 The practical lessons of both identification theory and research on perspective taking are clear:

To “put yourself in the other person’s shoes” is almost the only rule needed to ensure a good presentation: judge everything you do from the perspective of the listener. In doing so, a presenter can learn how he should formulate his argumentation, how he should organize his presentation, what sort of language he should use, how he should utilize presentation media, and what the appropriate body language is in the performance of his presentation.90

In one-on-one and small group persuasive situations, the projective calculus required to generate identification is relatively simple: an orator only has one or a few potential audience members that they need to consider. In rhetorical situations that contain larger or more diverse audiences, however, the calculus becomes significantly more complicated. Because each individual in an audience has their own opinions, attitudes, and beliefs about both the speaker and the topic at hand, it is not possible for an orator to fully account for the wide range of differences present. In other words, there is no way for an orator to generate identification with everyone in their audience. In situations in which a speaker is giving a presentation to a room full of people, for instance, their best hope is to make some generalizations about their audience and broadly tune their text and performance to the group at hand. The more knowledge that a speaker has about their direct audience, the more they are able to identify with their audience’s preexisting values, beliefs and attitudes, and the better they are able to integrate this insight into their speech and their performance—and thus, the more persuasive they will be.

This situation becomes even more complicated when an orator’s persuasive message is designed to reach multiple audiences, and when this persuasive message is delivered over a period of time. The realm of persuasive campaigns exemplifies such complexity: because the persuasive message is often deliberately distributed in different forms over time, there are a wide array of different individuals, groups, and organizations that the message might target and reach. As Manheim describes it, “the more sophisticated the campaign, the more it employs the differentiation of messages, the segmentation of audiences and other techniques.” In such situations, “different observers, or targets, will quite literally experience the campaign differently.”91

In such cases, the concept of audience splitting illustrates some of the complexity involved in an orator’s strategic calculations regarding their target audience(s).92 To use an example discussed above: when an advertising agency formulates a slogan for a product (e.g., “The King of Beers”), they may consider a single, primary target audience (e.g., middle-class, white males between the ages of 21–50). It is clear that there will be a wide variation of attitudes and opinions within this broad group regarding both the orator (in this case, the specific brand of beer) and the topic itself (beer in general), but the advertising agency can make some generalizations about this target audience and gear its texts and selection of performative contexts appropriately. At the same time, however, the advertising agency must also consider the attitudes and opinions of all of the people who may see their ad but are not in their primary target audience; this might include children under the age of 18, women, people of non-Caucasian ethnicities, or those higher or lower on the socio-economic ladder. Each of these secondary audiences may also see the advertisement, even if it is not directly intended for them. In order to avoid damaging their overall brand image, the advertising agency should seek to minimize negative reactions from such secondary audiences. On the other hand, they might also seek to expand their target audience in subsequent advertisements by incorporating the attitudes, beliefs, and values of a secondary audience complex. Thus the

core message can then be subdivided and differentiated to match the wants and needs of separate audiences or separate subsets of the same audience, so long as the partial messages remain consonant with one another so that differential messaging that overlaps into adjacent spaces does not create the impression that the campaign is inconsistent, saying one thing here, another over there.93

In addition to considerations of multiple audiences, orators acting within persuasive campaigns must consider a wide range of other actors in society that might help or hinder their persuasive efforts on their target audience. Because certain individuals and audience complexes will display resistance to persuasion by the orator, effective campaigns seek to operationalize the wide array of social and institutional networks that surround themselves and their target audience to reduce such resistance. A hypothetical example from the realm of political rhetoric can illustrate this point. An organization devoted to implementing anti-abortion legislation seeks the passage of a particular law currently under consideration by the legislature. The organization may seek to directly convince the legislature to vote for the bill by presenting its case in meetings with lawmakers. These lawmakers represent the primary audience of such messaging because they are the ultimate targets of persuasion (and action). At the same time, the anti-abortion organization may seek to influence other groups and individuals in society to put pressure on the lawmakers to pass the law: they may place a public advertisement in a lawmaker’s home district in the hopes that their constituents will call their representative, they may enlist other institutional groups to help their lobbying efforts (e.g., churches and religious leaders, medical associations and experts, allied anti-abortion organizations), or they may seek to gain media attention to raise public awareness and to build pressure on lawmakers to act. Any or all of these strategies may become a part of the coordinated campaign, and these outside intermediaries can be considered secondary audiences that may become nodes in an oratorical network for the purposes of the campaign.

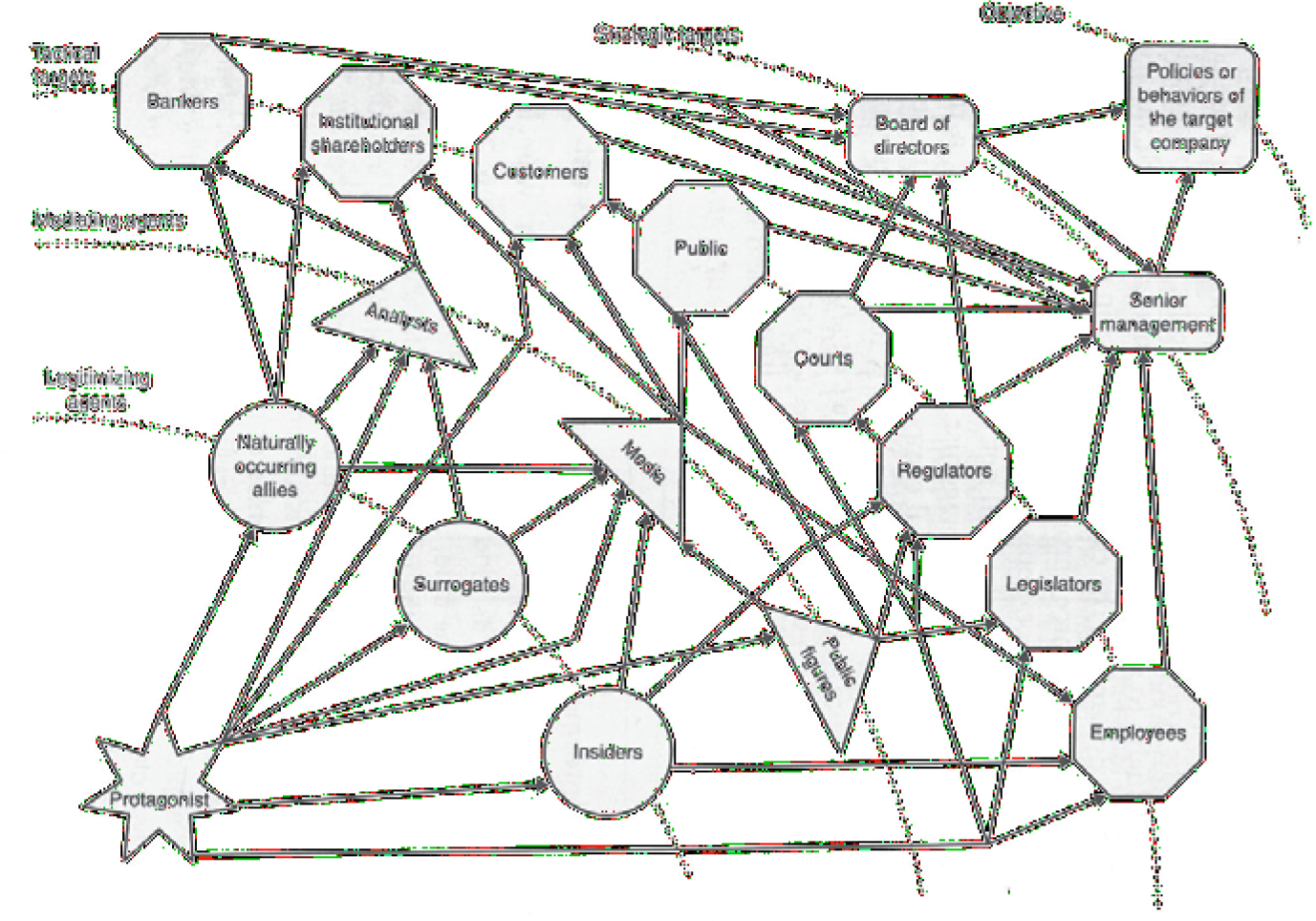

Manheim’s work devotes significant space to describing such networks and intermediaries, and how such elements can be instrumentalized to best influence target audiences. In addition to the protagonist (orator) and the target, Manheim describes “six principle types of intermediaries, any one or more of which may play a vital role.”94 By mapping the social and stakeholder network surrounding analyzing such dependencies, an orator can identify the stakeholders and influencers who may be most effective at delivering their message to their target for them:

The strategic objective is to bring to the support of the protagonist the energies and resources of other actors on whose support the target depends […] and to convert these third parties into de facto agents of the campaign or, if you will, force multipliers.95

In terms introduced above, an orator that seeks to influence a given target may be best served by attempting to form an oratorical network made up of different stakeholders in society that can deliver its message to the target from a variety of different angles.

Visualizing oratorical relationships and network connections can also be extremely helpful for the rhetorical analysis of real-world campaign communication. Doing so can shed light on oratorical goal setting and strategizing as well as help identify primary and secondary (target) audiences for a given persuasive message. Additionally, the analysis of an oratorical network can demonstrate how strategies, messages, and specific textual elements flow from one node to the next, and how each node has a specific function within the campaign. Such diagramming might show, for instance, how a given organization’s persuasive text is deliberately disseminated to supporters, the media, and other political and social institutions, and how this text is passed on (or modified or refuted) by these intermediaries to further audiences (including the ultimate target audience).

Manheim provides multiple ways in which such a network can be visualized and offers sample diagrams for different types of network structures. Figures 1 and 2 below are taken directly from his work and provide a few relevant examples. While Figure 1 diagrams some basic network structures, Figure 2 illustrates the level of complexity that oratorical networks may have: it visualizes a campaign in which a protagonist (bottom left) seeks to influence the policies and behaviors of a target company (top right). Between the protagonist (in rhetorical terminology, the primary orator) and their strategic target are a series of intermediaries that can be used to put pressure on the main target by making them nodes in an oratorical network. The protagonist may seek to influence these intermediaries directly or may seek to get others to indirectly influence them on behalf of the protagonist. Manheim further details the specific functions that certain intermediaries (nodes in the network) may have:

Where the protagonist lacks credibility or legitimacy, it will recruit allies or surrogates to speak on its behalf, thereby lending the effort their own, presumably higher, standing. Where the protagonist lacks access to the public or some other, more specialized audience, it will recruit or find ways to “manage” mediating agents such as prominent politicians, celebrities, or prominent intellectuals […] or various news or other media, to deliver its messages. Where the protagonist lacks access to, or influence with, the target […] it will recruit or find ways to mobilize stakeholders of the target as more direct points of pressure.96

1.3.2Setting

In addition to considerations of audience, rhetorical contexts include a wide variety of setting-based factors that must be taken into account during oratorical planning. In order to better categorize specific setting-related elements, rhetorical theory distinguishes between situative and dimissive settings, each of which brings with it its own types of contextual resistance that require oratorical effort to overcome.97

Situative settings involve in-person situations in which an orator uses their own voice and body as a medium to deliver their persuasive text directly to an audience that is present in the same space. Elements that must be taken into account during rhetorical planning and performance in face-to-face situative settings include the size and shape of the space, the time of day, the ambient temperature, the available assistive media (including microphones, overhead projectors, etc.), and, naturally, the situative audience that the speaker is addressing. Dimissive settings are those in which the orator is not directly present, and where the persuasive text is delivered to the audience through audio or visual channels that require a technical medium (such as television, radio, newspapers, the internet, etc.). In such situations, the orator is not only confronted by medial resistance (as determined by the structural limitations of the chosen medium) but also by a loss of control over the circumstances in which their persuasive text and message is received by a dimissive audience. To return to our example from above, a subway poster that advertises for “The King of Beers” is limited by the constraints of the medium poster, and may be seen by individuals who do not belong to the orator’s planned target audience(s).

Considerations of setting variables—and a recognition of the differences between situative and dimissive settings—are particularly important for the rhetorical strategy of polarization. As will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 2, orators that intend to use polarizing strategies must account for the broad reach of dimissive communication and the dangers that come with delivering polarizing messages across a wide variety of audiences. Similarly, successful polarization depends on clearly defining whether the situative audience or the dimissive audience (or both) should be polarized, and how best to set the process of polarization into motion in both types of settings. To give a brief example that will be explored later: within the context of elections, orators often deliver polarizing texts when giving campaign speeches to a situative audience of political supporters. In such cases, the effects of polarizing language may vary widely between situative and dimissive audiences. As research has shown, politicians have taken advantage of this difference and functionalized their immediate situative audiences and settings to increase the polarizing effect of their dimissive communication.98

In addition to the importance of situativity and dimissivity within the context of the strategy of polarization, these elements are also critical in persuasive campaigns, where multiple instances of communication across multiple different media must be coordinated together to form a cohesive message. In order to meet campaign goals, orators and orator complexes must account for how their persuasive messages will be delivered and received both situatively and dimissively and must consider the formats that will most effectively persuade both their primary target audience and activate the stakeholder network surrounding them. More specifically—and as will be shown in Chapter 3—individual orator complexes within the tea party network implemented polarizing strategies using texts containing the polarizing makers vs. takers framework in both situative settings (e.g., campaign rallies, public demonstrations) as well as dimissive settings (e.g., television and radio interviews, campaign print material, online posting). In the analysis to come, it will be important to identify the situative and dimissive factors that influenced tea party rhetorical strategizing, and to illustrate the ways in which tea party orators functionalized both types of settings to reach their target audiences and the networks surrounding them.

1.4Summary

The purpose of this chapter has been to lay the theoretical foundations for the work to come. Because rhetorical scholarship over the past century has splintered into a diverse array of disciplines and sub-disciplines, it is important to provide a clear terminological and theoretical framework that both establishes rhetoric as an independent discipline and that can be practically utilized in rhetorical analysis and planning. The result of this discussion is clear: contemporary rhetoric deals with persuasive communication that is strategically formulated and performed to influence specific audiences to think (and ultimately act) in a way that is beneficial to the orator. This core idea—that a well-executed rhetorical strategy can result in persuasive texts which set rhetorical processes in motion in an audience—will be especially important in the work to come.

Further, there are three core elements of contemporary rhetorical theory: the orator (as the strategically acting communicator or communicators), the text (as the communicative product of rhetorical efforts), and the context in which communication takes place (including the audience and the situation). These elements form the foundation of both rhetorical practice and the post hoc analysis of real-world persuasive communication, and each will represent an object of analysis in Chapter 3.

Before this analysis can take place, however, we must first turn our attention to polarization as a rhetorical phenomenon. The chapter to come will discuss well-established concepts of polarization in neighboring fields and will provide a detailed overview of existing research on the rhetorical strategy of polarization. By synthesizing this research and identifying the relevant oratorical, textual, and contextual characteristics of rhetorical strategies of polarization, Chapter 2 will show how a successfully executed strategy of polarization results in specially formulated polarizing texts that trigger polarizing processes in target audiences.