14

Theory of Political Culture

Introduction

England is a parliamentary democracy, so is India. There are Members of Parliament, political parties, interest and pressure groups, and electorates in both countries. This means there should not be any fundamental differences in the functioning of the two democracies. However, political parties, pressure and interest groups, electorates and their representatives behave differently in the two countries. Electorates and political leaders belonging to different regions even within India behave differently. When the institutional arrangements and democratic set-up are more or less the same, what are the factors that make the functioning of the English democracy different from the Indian democracy? What are the factors that make political process and functioning of democracy vary across regions even within India? Behaviour of voters, sympathizers, protestors, interest and demand groups, political leaders and political parties may not be the same in Delhi, Chennai, Kolkata and Patna. What factors will explain the difference in the behaviours, attitudes, beliefs, orientations and values of the voters, leaders, groups, etc. In short, what is ‘the socio-psychological environment of the political system’1 as Higgott says? Students of political studies and political sociologists, explore the sociological and psychological dimensions of political system. How do the psychological and social aspects of human beings influence the political aspect? Almond and Powell describe political culture as ‘psychological dimension of the political system’.2 Similar to the social behaviour of people with reference to culture or economic behaviour with respect to economic culture, we understand the political behaviour of the voters and citizens with the help of political culture.

Various factors may influence development of people's socio-psychological attitude towards the political system and its other components. Alan R. Ball talks of historical, social, economic, ethnic and colonial factors.3 Historical factors influence development of political attitudes of people. In England, the co-existence of subject or traditional elements with that of the democratic or participant elements, provide an example. In fact, the Conservative and Labour parties present two different options and political sub-cultures. Thus, British political culture is an example of historical continuity where the traditional and participant coexist. On the other hand, France presents a historically contrasting example. The French Revolution introduced new values of ‘liberty, equality and fraternity’ and democratic participant structures.

Transformation from feudal economy to capitalist-industrial or socialist–industrial also affects the attitude of the people towards the political system. In socialist countries, the political system itself seeks to regulate political orientation. There is limited or no scope for political orientation to input objects or self as active participant. This is because there is regulation of demands and interests as well as participation. The type of economy—capitalist, socialist or mixed—will also influence the development of political culture. This will influence absence or presence of demand and interest groups, their capability to assert and expectations from the system. Economic factors such as industrialization, urbanization and large working population, on the one hand, and agrarian, farming and large peasant population, on the other, contribute differently to the development of the political culture. Ball maintains that while the first will support a liberal democratic attitude, the second will present a conservative situation. It is generally held that agrarian rural economy is prone to parochial and subject orientation, while industrial urban economy tends to support participant culture.

Ethnic composition of a society also influences the development and nature of political culture. In most of the European countries, development of the nation-states has been on the lines of mono-ethnic character—French, German, English, Polish, Serb, etc. However, due to geographical migration, these countries have also accommodated immigrant ethnic groups. As such, a homogenous political culture requires consensus amongst all groups. The issue of ethnic adjustment in USA and Canada has different aspects. While USA has adopted the ‘melting pot’ model for assimilating ethnic groups, Canada has strong ethnic manifestations, at least, from the French. In many European countries, ethnic sub-cultures are manifest. The Irish and the Basque (Spain) problems are such examples. Ethnic differences have been a factor in the democratic instability in developing countries. Observers have pointed out that ethnic differences result in sharp social cleavages and fragmented political culture in many of the African and Asian countries. In fact, it has been argued that the introduction of a multi-party democratic set-up in societies with fragmented political culture has led to further aggravation of division. This is because multi-party competition needs to draw its social infrastructure and social bases from society and in many cases this reinforces the existing divisions. In India, for example, mobilization of castes in multi-party competition, particularly after the late 1960s, provides such an example. It appears that coalitional instability in India after the 1967 elections, both at the State and the Union level, is a reflection of mobilization of ‘middle castes’ and ‘lower caste’ as separate from the Congress model of ‘patron-client’ mobilization.

In developing countries, the legacy of the colonial past leaves its mark on the development of political culture. It is said that colonial administration created ethnic and social differences for administrative conveniences, which have revisited to disturb the development of a homogenous or, at least, a coherent political culture. Secondly, depth and intervention of the colonial administration also differed from region to region. In India, for example, in economic terms, the British introduced or reinforced three types of land relations—zamindari (right of land and revenue collection of an area to a feudal chief), mahalwari (revenue collection on the basis of collective grant) and ryotwari (village based revenue collection) in different areas. Politically, the British followed the policy of segregating regions and areas under their own direct control from those, which were princely states. The implication was that while British direct intervention could not influence the princely states, the latter followed their own policies. Arguably, if British rule in India is taken as an instrument of modernization and reform through social legislation, then there were areas in which these changes did not apply. Further, gradual introduction of self-government in India by the colonial rule was slow to sip in the princely states. Political participation and political socialization must have been restricted in princely states compared to the directly governed areas. Theoretically, it can be said that areas affected by the system of zamindari are more suited to patron–client orientation and parochial political culture, while areas under a princely state must have been prone to subject political culture.

On the other hand, the legacy, which became part of the anti-colonial struggle in India, gave a lasting thread to evolution of political culture in post-independent India. Particularly, two aspects are important: (i) Gandhian legacy of protest and antipathy to the political system as alien, and (ii) mass mobilization of people and their politicization. The first still renders its duty and we see our polity full of protests. The second has rendered people in many parts of the country to a participant political culture. The first creates an affective orientation of rejection of the political system opposed to people's interests, the second, helps people actively participate in the system. A combined effect of British policy and administration and nature of our anti-colonial struggle has been a fragmented political culture, either in terms of co-existence of traditional and modern political cultures or elite and mass political culture as Myron Weiner says. A national, centralized and dominant political culture, which is modernizing co-exists and competes with a traditional sub-culture. Myron Weiner has characterized India's political culture in two parts—Elite and Mass Political Culture, which we will discuss in the following sections.

Political Culture and Public Opinion

Traditionally, we have been appreciating the Aristotelian notion that a large middle class with a balanced socio-economic position is crucial for stable democracy. Similarly, the Lockean notion that majoritarian consensus is important for democratic consent and decision-making, has been an integral element of our political thought. J. S. Mill and Alex de Tocqueville, however, introduced an element of doubt and cautioned us to guard against ‘majoritarian tyranny’. What are the implications of the presence of a balanced middle class, majoritarian consensus or majoritarian tyranny for the functioning of democracy? Do they refer to presence of a public opinion that is behind the institutional and formal mechanism that democracy represents? Rousseau had talked about General Will and wanted it to be the potent-all force behind the civil society. When we talk about public opinion or Rousseau's general will, what do we mean by it? Is it a mix of emotional and rational, sentimental and logical, consensual and fragmented and individual and collective feelings, thoughts, attitudes and orientations? Relationship between democracy and public opinion has always been a crucial matter of debate in political theory. Healthy public opinion has been considered essential for the functioning of a democracy. Contrarily, elitist theorists argue that there is no possibility of a public opinion as it is always manufactured. Schumpeter, Sartori and other supporters of the elitist theory of democracy hold this view of ‘manufactured’ public opinion in a democratic set-up. Notwithstanding contrary views, public opinion can be treated as the operating system on which democracy as the application software works. Democracy requires supportive and healthy public opinion for its functioning and stability.

Political culture as an analytical concept can be understood with respect to what traditionally has been regarded as public opinion. At times, however, we also refer to the behaviour of the people of a nation in terms of national character referring to the collective psychology of the people as if they have a common feeling, thought, behaviour and attitude. However, while public opinion is taken as a short-term and amorphous opinion not always grounded in values or social reality, political culture seeks a long-term and value-based explanation of people's behaviour, attitudes, beliefs and orientation. The concept of national character is somewhat superficial, as it does not take into account the internal class and other divisions or for that matter, the exclusion of subdued minority.

Political culture refers to the social, psychological and behavioural environment within which citizens and voters act, react, conduct and express their political behaviour and orientation towards the political system and political issues. Whether people see authority of the state with allegiance and are participative in the political process or whether they are passive, protesting and apathetic towards the political system and its processes. Whether there is consensus or conflict amongst the public regarding policies, programmes and political aspects. Political culture implies emotional and attitudinal environment within which the political system operates. How beliefs, values, attitudes, inclinations, socio-psychological orientations of the people or a section of them define their relationship with political system and institutions. Whether people stand up and sing the national anthem when it is played or salute the national flag in deference when unfurled is a matter of orientation to the political system. Almond, Powell, Strom and Dalton in their Comparative Politics Today (2005) have described a nation's political culture as ‘public attitudes towards politics and their role within the political system.’4

It may appear that political culture is similar to public opinion. However, political culture differs from public opinion in that the latter is more a reaction to certain policies and issues and that too of temporary nature. Political culture, on the other hand, is based on long-term values. For example, there may be public opinion on desirability of a uniform civil code in India and enthusiasts may claim to prescribe a uniform civil code legally for all communities irrespective of their religion. However, public opinion may not provide a long-term basis for a rational and secular attitude amongst the whole populace. While the public opinion may be in favour of a uniform civil code, this may not be based on a long term secularized attitude. In fact, demand for a uniform civil code maybe a demand of sub-culture. Similarly, public opinion may be against unstable coalition governments but widespread support to a competitive multi-party system can be found in the orientation of the people.

How do people view the political process, what importance do they attach to institutions such as election, political parties, parliament, representatives, etc.? Are voters inclined to vote on caste lines or are they individual decision-makers? Do they like regional issues to be given importance or do they prefer issues of national importance? Are people enthusiastic about elections or are they apathetic? Are people sharply divided in their preference on parliamentary versus presidential democracy? Is there consensus amongst the people, or at least a majority of them, on major political issues, or are they divided in their value preferences? All these questions are related to the socio-psychological aspects of individual political behaviour. People have different attitudes, orientation and ways of relating to political institutions, processes and events. Allan R. Ball defines political culture as ‘composed of the attitudes, beliefs, emotions and values of society that relate to the political system and political issues.5 Whether people's orientation is supportive and cooperative towards the political processes and institutions or whether they are conflictual and resisting; whether there is consensus or division. Political culture as an analytical unit helps us understand these issues. Why do we say that some voters have behaved as ‘vote bank’ and some others have voted as per individual decisions. This may happen because different groups of people may relate themselves in a different way towards the political system.

Political culture as a unit of analysis emerged out of the behavioural revolution and is related to the discipline of political sociology. Study of political culture helps in knowing how individuals, groups and society relate to the political system, processes and various institutions. Political culture locates factors and processes that lead to stability, consensus, cooperation, acceptance of authority and obedience to the laws of the state. In a way, it aims at exploring consensus in the society and those conditions which are needed for a liberal democratic stability and order in the capitalist-industrial state. Political culture helps in understanding how different political systems work in different socio-psychological and behavioural environment. It provides a useful conceptual tool to compare different democracies by comparing how different political cultures produce different democratic experiences.

Political culture reflects conscious or sub-conscious, explicit or implicit attitudinal and behavioural aspects of public. Creation and sustenance of political culture is a long-term process. It is said that political culture reflects orientations, inclinations and tendencies of the public, which have its base in long-term values. For example, Gandhian means of protest may be more acceptable than a violent means because they were employed against the mighty British Empire successfully. Respect for authority, for example, is not manipulated in one day, rather it emerges right from the school days or childhood in the family in the form of discipline, queuing, obeying, etc. People may carry an attitude of respect for authority implicitly when they relate to political aspects also. This process of making people imbibe certain attitudes and behaviour is called political socialization about which we will deal later.

As a conceptual tool or analytical unit for understanding the political system, many political theorists have carried out studies of political culture. Gabriel Almond, Sidney Verba, G. Bingham Powell Jr, Lucian W. Pye, James Coleman and others have been pioneers in this area. Almond and Coleman (eds) The Politics of Developing Areas used the concept of political culture for comparative studies. In the introduction of the book, Almond explained the behavioural approach and introduced new concepts such as political system instead of ‘state’. He further explains, ‘instead of ‘public opinion’ and ‘citizenship training’, formal and rational in meaning, we prefer’ political culture’ and ‘political socialization’.’6 This means political culture is a behavioural concept and includes an informal socio-psychological process. Unlike public opinion, which is a currently held opinion, political culture refers to value-based orientation of the public.

Political Culture as ‘Civic Culture’

Gabriel A. Almond and Sidney Verba's The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations (1963) presented a study of political cultures of five democracies—Britain, Germany, Italy, Mexico and the United States. The study seeks to locate the attitudinal and behavioural aspects of the people, their orientation towards authority, political objects and political system, reconciliation of their differences and consensus building as suitable to democratic polity. The hypothesis that ‘the civic culture appears to be particularly appropriate for democratic political system’7 is a reflection of this attempt. It is an attempt to explain or understand the ‘characteristics and preconditions of culture of democracy’. In their study of civic culture, as Almond and Verba says, ‘rather than deriving the social-psychological preconditions of democracy from psychological theory, we have sought to determine whether and to what extent these relations actually exist in functioning democratic systems.’8 In studying five democracies, they have sought to find out how stability and successful functioning of democracy is correlated with social and psychological preconditions.

Based on this correlation, they have asked as to what are the specific characteristics that political culture must possess to be called civic culture and be suitable for successful democratic experience? In Chapter 1, ‘An Approach to Political Culture’, Almond and Verba have characterized ‘civic culture’ as ‘third culture, neither traditional nor modern, but partaking of both; pluralistic culture based on communication and persuasion, a culture of consensus and diversity, a culture that permitted change but moderated it. This was civic culture.’9 It appears that ‘civic culture’ is characterized as a particular type of political culture, which is considered suitable for democratic functioning. Logically, for Almond and Verba, political culture becomes ‘civic culture’ and civic culture is ‘democratic culture. It includes characteristics of:

- Pluralistic culture that entertains diversity

- Consensus and persuasion

- Change with moderation

- A mixed political culture—mix of traditional and rational elements

- Parliamentary representation

- Political party that co-ordinates and convert demands and interests into policy perspectives and realizable programmes

- Neutral and responsible bureaucracy

- Bargaining interest groups

- Autonomous and neutral media of communication

- Allegiant participant culture in which political culture and political structure are congruent

A political culture with the characteristics mentioned at (i) to (x) is considered appropriate for stability of democracy and its proper functioning. Civic culture is not considered as ‘a modern culture, but a mixed modernizing traditional one’. According to Almond and Verba, in England, which they consider as one of the important examples of civic culture, secularization took place due to separation of church and toleration of religious diversity, but on the other hand, the traditional aristocratic and monarchic forces also were assimilated.10 A mix of rationalism and traditionalism characterizes civic culture.

Civic culture focuses on the psychological insights of individual orientation to political objects. What factors influence the way people participate in the political process. Active citizens participation in the civic affairs and sense of civic responsibility were celebrated by the Greeks as reflected in Athenian democracy; it was cherished and insisted by John Stuart Mill as required for individual intellectual and moral self-development and was found to be one of the favourable conditions for democracy by James Bryce. Rational and active participation is considered as an important factor in classical democratic theory. With its emphasis on rational participation, Almond and Verba calls the classical model, as ‘rationality-activist’ model of political culture. They explain civic culture as rationality—activist plus something else.11 ‘Something else’ comes from the fact that people are not only oriented towards inputs, structures and process but are positively oriented. In other words, the political structure and orientation of the people match with each other or they are congruent. As such, ‘the civic culture is a participant political culture in which the political culture and political structure are congruent’.12 Aspects of congruency and incongruency between political culture and political structure have been dealt with later in this chapter. The way people participate in the political process reflects their orientation towards the political objects. Further, nature of orientation towards political objects determines the types of political culture that obtains. Almond and Verba define political culture as referring to ‘specifically political orientations—attitudes towards political the system and its various parts and attitudes toward the role of the self in the system’. To appreciate the orientation of citizens to the political system, we may have to understand some concepts such as ‘political orientation’ and its dimensions, and ‘political objects’. Almond and Verba deal with them to classify the types of political culture that can prevail based on orientation of the people.

‘Orientation’ has been explained as ‘the internalized aspects of objects and relationships’. In other words, it is inclination towards certain things or certain relationships that emerges not from temporary reaction or opinion but as a matter of socialization and value-based attachment. For example, we respect our national flag not merely because it has three beautiful colours, or that it is unfurled by the President and the Prime Minister, but primarily because it is a symbol of national collective unity, sovereignty and pledge of national freedom. Unfurling of the national flag reconfirms the values of the Constitution of India. In a different way, this orientation has been beautifully captured in a popular promotional snippet where an old cobbler sitting on the roadside along with young cobblers amidst rain, unfortunate to have lost his one leg, stands up on the playing of the national anthem of India on radio. His instant standing and paying respect is a reflection of internalized values towards the national anthem.

Almond and Verba, following Talcott Parsons and Edward Shills who have suggested three classes of orientation in individual's actions, classify political orientations13 as: (i) cognitive orientation, (ii) affective orientation, and (iii) evaluative orientation. Cognitive orientation, coming from cognition, refers to knowledge of and belief about the political system, roles and those who play the role, inputs and outputs, etc. Affective orientation implies emotional and sentimental aspects of individuals towards political objects. It refers to the feeling of attachment, involvement or rejection. Evaluative orientation is related to judgmental aspect and refers to judgements and opinions about political objects. Evaluative orientation combines value standards and criteria with feeling and information. It means evaluative orientation is based on cognitive and affective orientation. The significance of the three classes of orientation is that to be an active participant in the political process, a citizen needs to be aware of the political system and its various aspects, must feel related to the political objects and must evaluate its performance and functioning.

Political objects are the political system and its component parts such as roles and structures such as legislature, executives, bureaucracy, etc. incumbents of roles such as legislators and administrators, etc., and policies, decisions or enforcements towards which political orientation is related. Political orientation is also related to ‘self’ as political actor in terms of political obligation and personal competence. Orientation towards the political system (roles, structures, incumbents and policies, decisions etc.) can also be in terms of inputs and outputs.

As Almond and Powell14 say, an individual may have a high degree of knowledge about the working of the political system, the leading figures and current problems and policies. Alternatively, one may have very low knowledge of the same. This relates to cognitive dimension. On the affective dimension side, one may be supportive of the system and its policies and have a feeling of attachment. Alternatively, one may have a feeling of alienation and apathy towards the system and may not respond with support when the system demands. Thirdly, one's democratic norms may make him/her evaluate the responsiveness of the system to the democratic demands or may make him/her evaluate ethically the level of corruption or nepotism in the system. This relates to evaluative orientation. The implication of nature of orientations is that it will influence the working of the political system.

It appears that Almond and Verba's study, The Civic Culture, provides two parallels, one of Weber's ideal type and the other of Bryce's Modern Democracies. Almond and Verba have sought to create an ideal type of such a political culture that provides a ‘fit’ between democracy and socio-psychological orientation of people. In other words, the socio-cultural orientations of the people should be congruent to the requirements of the political structures and roles. This study also reminds us of the study of James Bryce's Modern Democracies (1921) in which he compared six democratic governments—Australia, Canada, France, New Zealand, Switzerland and the United States. While Bryce focuses on formal-institutional aspects of these democracies, Almond and Verba look into the socio-psychological environment and informal aspects of the functioning of democracies. Bryce in Chapter 67 ‘Comparison of the Six Democratic Governments Examined’ of his book, while discussing the presence or absence of conditions favouring democracy, mentions about ‘sense of civic duty’, ‘sentiment of national unity’, etc., as requisite conditions. They are behavioural orientations and Bryce treats their presence or absence as credit or discredit to democratic institutions.15 On the other hand, Almond and Verba's study adopts the behavioural approach. Compared with each other, both Modern Democracies and The Civic Culture are studies of democratic systems. The former focuses on formal-institutional aspects, the latter studies behavioural aspects. Comparison of the two studies shows a shift in political studies from the formal-institutional approach in the first quarter of the twentieth century to the behavioural approach in second-half of the twentieth century.

At times, it appears that civic culture is a product of historical factors including secularization and a democratic government, on the other hand it appears to be an ideal typical goal to be followed if countries of the third world were to achieve democratic stability. Either way, evolution of the concept of political culture as civic culture has its euro-centric or Anglo-American bias. Almond and Verba evolve ‘civic culture’ as an ideal type based on the characteristics of evolution of democracies in five countries—Britain, Germany, Italy, Mexico and the United States. The ideal type tends to become prescriptive for democratic stability in developing countries as civic culture is taken as an ideal typical creation from the experience of political culture of ‘stable and successful democracies (of) Great Britain and the United States.16

Almond and Verba revisited the political systems in Germany, Great Britain, Italy, Mexico and the United States to study and compare their political cultures and have presented their conclusions in The Civic Culture Revisited (1980).

Types of Political Culture

Degree and nature of political orientation in terms of cognitive, affective and evaluative can become the basis of classifying political cultures. These include level of knowledge (cognitive), nature of feeling (affective) and opinion and judgment (evaluative) about:

- The system in general and the political system

- Constitutional characteristics and power

- Inputs (policy proposals)

- Roles of political elite, leadership and groups

- Structures (parties, legislature, executive, bureaucracy, judiciary and other incumbents)

- Outputs (policies and decisions)

Further, orientation towards ‘self’ as an active political actor and participant also becomes an important factor in classifying political cultures. Whether participants have knowledge of their rights, obligations and power and influence that they can exercise and what do they feel about their capabilities or lack of it. How do they evaluate and judge the performance of the political system? Does one evaluate it as less democratic and less responsive to demands of the people? Almond and Verba seek to map political orientation towards political system in general, input and output aspects and the self as a political actor.

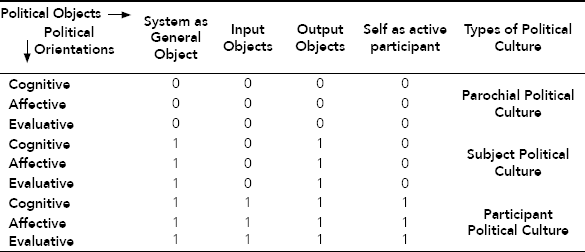

Based on dimensions of political orientation (cognitive, affective and evaluative) of the individuals towards political objects (system as a general object, input objects, output objects and self as active participant), Almond and Verba have classified types of political culture.17 They classify political cultures in three categories: (i) Parochial Political Culture, (ii) Subject Political Culture, and (iii) Participant Political Culture. Each of them are characterized by degree of presence or absence of the level of knowledge, feeling and opinion and judgements about the political system, in general and its elements—inputs and outputs, and self as participant. Almond and Verba have graded the degree of presence or absence of cognitive orientation, nature of affective and evaluative political orientations to assign characteristics to a particular political culture (see Table 14.1).

Table 14.1 Types of Political Culture18

Parochial political culture is related to political orientation that is characterized by little or no awareness amongst the people about the political system in general, its inputs, outputs and even their role as political actors. Almond and Verba assign zero (minimal or low or absent) to all dimensions of political orientation. This happens due to lack of clear division between political aspects from that of the social and community aspects. The roles and structures are diffused and not differentiated. Lack of awareness also results in absence or little expectation from the political system. Absence or little knowledge of political system and its elements, less or no expectation from the political system and no standards or criteria of judging the political system lies at one extreme, which Almond and Verba designate as parochial political culture. In this, participation of the self is not considered as relevant for the political system.

However, this represents a pure parochial political culture in which there is little or no awareness of political objects, no feeling or uncertain feeling towards the political objects and no standard or criteria of evaluating the system and little or no political specialization. Further, the role of the self as an active participant is minimal or considered irrelevant. Nevertheless, there is a possibility of the individual being aware of political authority but is affectively uncertain or negative and has no norms of regulating relationship with it. This would represent variation from pure parochial political culture. However, the relationship between the political objects and the individual remains parochial, i.e., uncertain, diffused, distant and non-expecting.

Subject political culture is characterized by high frequency of political orientation towards a differentiated political system and towards the output objects of the political system. This means people are aware about the political system and authority and the impact of the outputs and policy decisions that flow downward. However, there is absence of political orientation towards input objects and towards the self as an active participant. Here the individual is aware of government authority and is attached to it either by taking pride in it or disliking it. There is also evaluation of the system either as legitimate or otherwise. The orientation, however, is restricted towards the system at a general level and aspects of output objects such as policies and decisions flowing downward. On the other hand, there is absence of orientation towards input objects and how demands and policy proposals are put upward.

However, this represents a pure subject political culture in which there is awareness of select political objects such the system and the outputs and their impacts. There is no feeling or uncertain feeling towards the other political objects such as inputs and how they are put forward. There is no standard or criteria of evaluating the system or relating oneself to it. This pure subject political culture is relevant where there is no differentiated input structure. In cases where there is developed democratic institution, it would be limited to affective and evaluative orientations rather than to cognitive orientation. However, the relationship between the individual (subject) and the political objects remain passive.

Participant political culture is characterized by high frequency of political orientation towards a differentiated political system, the input and output objects and role of the self as active participant. This means people are aware about the political system and authority and administrative structures and the requirements and impact of the inputs and policy proposals that flow upward and outputs and policy decisions that flow downward. However, there is active and explicit political orientation towards the self as an active participant. Here the individual is aware of government authority, administrative structures, structures of inputs and outputs and is attached to them either by taking pride in it or being a critical evaluator of the system either as legitimate or otherwise. The orientation is also explicit in terms of participation in the political process and articulation of demands and in outputs and making decisions. The role of the self as participant in the polity is ‘activist’ though participation may be in terms of support or rejection, i.e., favourable or unfavourable participation.

The three-fold classification of political culture by Almond and Verba does not mean each type eliminates or replaces the other. Subject orientation does not replace the parochial orientation or participant replaces the subject and parochial. Subject orientation adds to the existing diffused orientations, specialized orientation to government institutions. Similarly, participant political orientation is added as a layer to the existing parochial and subject orientations. However, Almond and Verba are of the opinion that adding successive orientations onto the existing ones do not mean the earlier ones remain unchanged.19 This leads to adaptation by old orientations to the newly introduced orientations. Nevertheless, there is a mix of participant, subject and parochial orientations and individual may display this mix of orientation. Almond and Verba term this as ‘citizen’. Civic culture is treated as a particular mix of citizens, subjects and parochials. Thus, three types of participants—citizens, subjects and parochials—are identified. Civic culture is supposed to include all the three types.

These three types of political cultures may generally be associated with three types of political structures. Generally, parochial political culture may be congruent with traditional political structure; subject political culture with authoritarian political structure and participant with democratic. This also implies that in case there is change in the political system and structures but no corresponding or proportionate change in the political culture, it would result in an incongruent relationship between the political structure and political culture. Almond and Verba present a position where there can be congruency or incongruency between the political culture and political structure. Implication of congruency between political culture and political structure is that attitudes and institutions match, while incongruency means attitudes reject political institutions and structures. Probably, this will explain, how many democratic institutions fail to function successfully in many developing countries. For example, Almond and Powell in their Comparative Politics (1966) have pointed out about examples of ‘lag between structural and cultural changes’.20 Introduction of adult suffrage brings a new institution as part of democratic set-up and requires that the voter's attitude should reflect individual rational decision-making. However, it may happen that voting may be done as per traditional norms. In India, for example, psephologists and political analysts have pointed out that in the aftermath of independence, voting in India has been characterized by ‘patron-client’ relationship. In this, mobilization for voting is not as per individual choice but by a socially determined relationship between somebody dominant and others as clients. This gap between requirement of a political institution (adult suffrage and rational choice-making) and attitudinal orientation (voting as per socially determined relationship) is incongruency between political culture and political institutions.

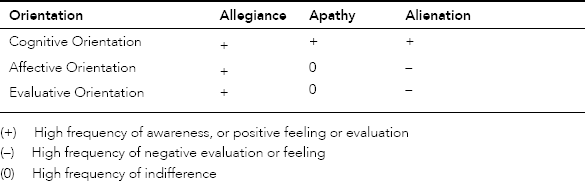

Almond and Verba have presented the relationship between political culture and political structure in terms of congruency (fit) and incongruency (gap) in the Table 14.2.

Table 14.2 Congruency/Incongruency between Political Culture and Political Structure21

Allegiant political culture is one in which cognitive, affective and participant political orientations reach a high frequency of awareness, positive feeling and evaluation. Here political culture and political structure fit each other or match and become congruent with each other. In fact, Almond and Verba have explained civic culture as one which shows allegiant characteristics and where political culture and political structure become congruent. This provides an essential condition for successful, stable and participant democracy. In a situation of high frequency of awareness but high frequency of indifference in feeling and evaluation, apathy prevails. In this, congruency between political culture and political structure is very weak. A third situation relates to one of high frequency of negative evaluation or feeling. In this, political culture and attitudes reject the political structures. This presents a situation of instability. As such, allegiance, apathy and alienation also stand for a spectrum of stable, weak and unstable democracies. For Almond and Verba, while stable democracies provide instances of civic culture, instability is found in most of the developing countries. With the help of concept of civic culture, democratic experiences and experiments of different countries can be analysed and classified as allegiant, apathetic and alienated in terms of congruency between political culture and political structure. However, it may be noted that all political cultures are mixed cultures and there are individuals with subject and parochial orientations. Almond and Verba's civic culture is also a mixed culture.

Since all political cultures, except the parochial political culture, are mixed, Almond and Verba present a combination of different political cultures as: (i) The Parochial-Subject Culture, (ii) The Subject-Participant Culture, and (iii) The Parochial–Participant Culture.

In the Parochial-Subject Culture, people have a mix of parochial and subject orientation. A large number of people may not accept only diffuse authority of the tribal, village or feudal chief. Contrarily, they are oriented towards a more complex political system with specialized and centralized authority such as a king, or a ruler. Almond and Verba cite the examples of African kingdoms22 and the Ottoman Empire (read Usmaniya or Uthmaniya from which the English version ‘Ottoman’ comes) as examples of mixed subject-parochial culture. Similarly, culture might have existed in many of the oriental empires in China, Egypt and India. However, the main feature of the centralized authority is its extractive nature. It may be mentioned here that Karl Marx while discussing about the Asiatic mode of production characterizes oriental despotism chiefly with extractive nature. Parochial–subject culture combines parochial orientation and subject orientation. Though the parochial orientation survives as sub-culture, its character changes over a period of time because of interaction with subject sub-culture.

The Subject-Participant Culture combines subject as well as participant orientations. England presents such an example where subject culture was supplemented by participant culture. A specific feature of this culture is that a substantial part of the population has acquired specialized input orientations and an activist set of self-orientation. This means people are aware of policy proposals that flow upward and they seek active participation in the inputs. However, input functions at times are based on available democratic infrastructures such as local authorities, local communities, municipal affiliations etc. Almond and Verba point out that if parochial and local autonomies survive, they may contribute to the development of a democratic infrastructure. They further suggest that in Britain these groups become first of the interest groups. In this, subject culture survives as sub-culture. Though the subject orientation survives as subculture, its character changes over a time period because of interaction with participant and democratic sub-culture.

The Parochial–Participant Culture is peculiarly identified with democratic participant structures and roles with parochial political cultures. In most of the third world or developing countries, though participant democratic structures have been introduced, the political culture remains predominantly parochial. We have mentioned above about what Almond and Verba say ‘incongruency’ and Almond and Powell say, ‘gap’ between political culture and political structure. Parochial-participant culture is characterized by such a gap or incongruency. This gap or incongruency explains the reason why democratic institutions functions differently, say in England and in India. While in England, voter's participation may be largely according to individual choices, in India it may be in the patron-client framework or as a vote bank. A participant democratic structure requires a participant political culture, absence of which leads to gap and persisting instability. A parochial political sub-culture will generally resist participant structures. Almond and Verba feel that to bridge the gap, parochial systems can be transformed into input democratic infrastructures such as demand and interest groups.

We may recall, Rajni Kothari's thesis of ‘politicization of caste and casteism in politics’ presented in the early 1970s in his Politics in India (1970). Caste as a traditional system presented parochial structure, which is now operating within a democratic participant environment. If we take caste as an element of parochial sub-culture and democratic polity as participant structure, Kothari feels that the two must work together to remove the incongruency that Almond and Verba talk about. Castes as parochial sub-culture needed to orient itself as interest or demand groups or may be as politically active participants in place of the self that Almond and Verba talk about. Thus, caste becomes part of democratic infrastructure and oriented to inputs, and democratic politics requires them as participants. Kothari's conclusion that ‘the alleged casteism in politics is thus no more and no less than politicisation of caste’23 point to the need of a participant democratic polity to search for its participant political culture. Democratic polity required its participants and caste groups needed a political process for asserting their identity and interests. Politics provides castes a platform to organize and express, caste groups provide politics democratic infrastructure.

Political Sub-culture

The discussion above suggests that the population as a whole may not display one type of political orientation. Political sociologists generally agree that diverse political orientations exist in society in different groups towards political objects. It means political culture is not homogenous but heterogeneous. Political sub-culture refers to existence of particular type of orientations, propensities or inclinations found in particular group of people as different from the other. Almond and Verba have demonstrated the co-existence of parochial and subject sub-cultures in their analysis of a combination of political cultures. They stress the fact that ‘even the most fully developed participant cultures will contain strata of subjects and parochials.’24 For example, a Subject-Participant Culture will contain a Subject sub-culture while a Parochial-Subject Culture will have Parochials as sub-culture. Thus, political sub-culture refers to political orientation located in a particular group and that c-oexists and competes with the dominant or competing political culture that has acquired centralized and national character. Almond and Powell suggest existence of ‘special propensities and patterns found within separate parts of the population’ and these special propensities or tendencies located in particular groups is called sub-cultures. All political cultures are mixed and heterogeneous. In Subject culture, Parochial sub-culture exists; in Participant culture, Subject and at times, Parochial sub-cultures exist.

Almond and Verba differentiate between two types of political sub-cultures: (i) policy sub-culture, and (ii) structure sub-culture.25 The first refers to policy differences that persist, e. g. between the Republicans and the Democrats in America, or between the supporters of monarchy (conservatives) and it opponents (socialist and labour) in England. In this there is agreement on the fundamental political structure. The second refers to heterogeneous political culture where different sub-cultures, that represent fundamental differences on the issue of form of political structure, exist. For example, Almond and Verba cite the example of post-French Revolution, where Republican versus subject-parochial sub-cultures existed.

A political sub-culture may arise due to differences on caste, class, ethnic, tribal and linguistic lines. In fact, many developing societies have socially fragmented orientation amongst the people. Due to these differences, social and economic factors, a highly fragmented society prevails. It contains sub-cultures and poses a problem of creating a common, centralized and nationalistic authority that could rally all the sub-cultures. A common symbol of centralized authority is lacking in many developing countries. This implies lack of a stable democratic set up and absence of a nationalistic and centralized authority. Many observers maintain that developing countries are characterized by the co-existence of modern and traditional political cultures. It is assumed that traditional political culture will subsequently give way to modern political culture. In fact, the criteria of ‘political development’ such as political secularization, sub-system autonomy and structural differentiations, imply emergence of a non-traditional political culture by replacing a traditional one.

Myron Weiner has differentiated between mass and elite political cultures and suggests that India's political culture is characterized by these two political cultures. We will discuss this separately.

Theorists of political culture have also discussed about traditional versus modern sub-cultures, at times dichotomous and at times co-existing. Division between traditional and modern subcultures are considered sharp in countries, which were under colonial rule and are experimenting with democratic regimes after independence. Post-colonial and developing countries, analysts and theorists of comparative politics point out, are characterized by a small educated elite with ‘universalistic and pragmatic orientations which typify ‘modern’ culture—while the vast majority remains tied to the rigid, diffuse, and ascriptive patterns of tradition.’26 At times, this dichotomy is generally associated with urban-rural dichotomy and at times with tradition-modernity dichotomy or co-existence. Focus on developing countries to study political culture in terms of modernization has led to the conclusion of presence and co-existence of modern and traditional subcultures. Studies on India in 1960s also focused on the tradition-modernity sub-cultural dichotomy/co-existence. Educated elite, industrial and urban economy, democratic political system, universal adult suffrage, autonomous associational and demand groups and secularization of polity were marked as elements of a modern political process. On the other hand, regional and parochial affiliations, caste and communal factors, patron-client relationship for electoral mobilization, etc., were considered as elements of tradition. These were presented as two subcultures implying thereby that as modern political sub-culture proceeds, the traditional sub-culture might recede. Myron Weiner, in an article in 1960 (‘Some Hypotheses on the Politics of Modernization in India’),27 has supported this view of political sub-cultures in India. Lloyd I. Rudolph and Susanne H. Rudolph, in their study The Modernity of Tradition: Political Development in India (1967), presented the view that traditional elements such as the caste system assisted in the development of modern, representative politics in India. They found modern elements in the traditional institutions that were appropriate for democratic politics. They also pointed out how caste groups formed horizontal associations and acted as demand and pressure groups besides acting as an organizing factor in electoral democracy. They called various caste groups and their Sabhas/Mahasabhas as ‘para-communities. Rajni Kothari's thesis of Politicisation of Caste and Casteism in Politics (Politics in India, 1970) also indicates sub-cultural coexistence in India.

Political Socialization and Its Agencies

In classical democracy, political training of citizens has been considered as an important condition for its success. Through political training, citizens are made aware of the requirements of a democratic government and process, expectations from them as participants and their rights and obligations. People form certain opinions and collectively manifest it as part of public opinion. How public opinion is formed and manifested, how different agencies in society such as family, peer group and other social relations, schools and educational institutions, mass media, political parties, political intermediaries and power brokers, religious institutions, etc. shape and change public opinion. Similar to this, political socialization means political recruitment of citizens in a particular political culture. Political socialization is political training and political recruitment of citizens to play a political role as activists and participants. What are the aspects of political socialization? How does political socialization influence political attitudes and behaviours of the citizens as participants or passive agents?

The agencies mentioned above a play crucial role in making citizens imbibe attitudes, beliefs, feelings and orientations about the political system, policies, programmes, symbols and various political aspects. What role the agencies of political socialization play and whether the democratic state or a non-democratic state can influence the political socialization of the citizens. Alan. R Ball explains political socialization as ‘the establishment and development of attitudes to and beliefs about the political system.’28 It is obvious that generally agencies of societies do not inculcate attitudes or feelings, which are inimical or disloyal. The objective of political socialization is to help citizens imbibe a feeling of loyalty towards the nation, obedience to the political system, positive values towards authority of the political system and encourage values that help establish a stable democratic government. We shall discuss what role political socialization plays in democratic stability.

However, the emphasis on stability, obedience and values favourable to the existing set-up also has a bias towards status quo. Many observers have pointed out that emphasis on stability in the study of political socialization is a reflection of concern to maintain stability and order in the capitalist-liberal democratic societies. We shall discuss these issues and analyse whether political socialization is meant to foster non-coercive dominance and hegemony in favour of an established system.

Political socialization has been understood earlier as a citizen's training in civic participation. Almond and Powell define political socialization as ‘the process by which political cultures are maintained and changed.’29 This means an individual's opinions, attitudes, orientations and beliefs are formed, shaped or inculcated in relation to political aspects. Political socialization inculcates orientations (knowledge, awareness, feeling, emotions, evaluation and judgements) towards political objects (nation or system in general, political system, inputs of policy proposals, demands and pressures and support, outputs of policy and programmes and self as an active participant).

If we read Almond and Powells explanation with that of Alan R. Balls definition given above, it appears that political socialization is not only helpful in establishment and development of attitudes to and beliefs about the political system, it also encourages changes in the pattern of political culture. As such, political socialization can be a means of maintaining the current political attitudes or inculcating new ones suited for the existing political system and political culture as well as changing it by introducing new elements. For example, it is generally agreed that the British colonial educational system and administrative set-up in India was geared to support the requirements of a colonial political system. English and liberal education was to create an educated middle class elite suited to colonial requirements. However, this very element also helped inculcation of national consciousness. Dual role of the educational system as agency of political socialization, on the one hand, to provide administrative, professional and business support to the colonial political system and on the other to foster national consciousness, is a case in point. A second example can be cited in the present Indian scenario. We have come across instances when governments seek to bring change in the history textbooks. By reinterpreting history or certain perceived facts in history, an attempt is made to revive an account of history that supports a particular socio-political orientation. It is meant to imbibe those attitudes and feelings that would help establish a particular political culture suited to a specific notion of a nation, state, political process and the role of the individual as self.

Political socialization as a process can be both status quoist as well as change-oriented. In fact, there has been an all-out effort in post-colonial and developing countries to inculcate a political culture that helps in nation-building and establishment of stable and centralized political authority. This is considered important because of the presence of fragmented political culture, divisive sub-cultures and parochial political affiliations and orientations. Political socialization is aimed at bringing consensus, or at least, a reconciled attitude. Political socialization in developing countries has a dual role—one, to inculcate emotional loyalty to a centralized authority by transferring from parochial and local loyalties which is important for nation-building, and two, to imbibe a democratic-participant attitude which is relevant for democratic stability. As such, political socialization in developing countries is more of a state-driven agenda to create a harmonious political culture suitable for democracy and nation building.

Political socialization is a continuous process and goes on through out the life of an individual. From early family experiences to school and peer group influences to direct political participation, political socialization takes place. Two significant aspects of such a continuous process of political socialization are: (i) changes in the attitudes and behaviours over a period due to changed experiences and rejection of one type of political orientation in favour of the other; and (ii) political socialization in the form of political learning and non-political learning. Political learning has a manifest objective of political socialization but non-political learning, e.g. obedience to authority of the teacher or the father leading to respect to political authority, helps in latent transmission of political culture. Thus, political socialization can take the form of both manifest as well as latent transmission. Political socialization takes place through political as well as non-political learning. Political learning implies explicit and direct communication aimed at transmitting information, values or feelings towards political objects. This is manifest political socialization. An example of such political socialization is teaching the subject of civics in schools.30 On the other hand, non-political learning may also be transmitted to the political realm that will affect attitudes towards similar political things. For example, familial or peer group attitude of tolerance or conflict and cooperation or competition may affect, in the long run, one's behaviour towards fellow citizens, political leaders and policy makers or politics as a whole. Based on non-political socialization, an analogous view of politics can be a mere struggle for power or struggle for dominance or alternatively, a means of attaining legitimate goals or as a means for equitable resource-allocation.

Viewed in terms of political and non-political socialization, political socialization can be looked at from both a narrow and a broader perspective. Narrowly, political socialization aims at deliberate inculcation of values, attitudes and orientations about the political system and objects and that is done by formal institutions. Political parties, for example, mobilize and train people in a particular way. Similarly, publicly or state-owned media disseminate and spread specific political messages and trainings that are directed in favour of the political system. Contrasted to narrow political socialization, there can be broad political socialization. In it, formal and informal agencies of socialization work and both political and non-political socialization with analogous behaviour are relevant. All learning, formal and informal that has a bearing on political behaviour, in a latent or manifest way, becomes part of broad political socialization. Instead of dichotomizing narrow versus broad political socialization, it appears that political socialization can take place directly or indirectly. After all, a liberal democratic political system cannot imagine separating itself from the value of individual freedom including that of private property rights. In a liberal-capitalist society, institutions of the society, family, schools, religious institutions, etc. are geared to support and safeguard these values. Citizens brought up in such contexts would bring their behavioural and attitu-dinal orientations to bear on the political system. Sociologists like Talcott Parsons have maintained that industrial society requires a nuclear family or industrialization necessarily forces a family to become nuclear. This being the case, a nuclear family suited to industrialization and competitive urban environment would necessarily take a view of politics that is most appropriate to its vision of life style—competitive and individual-based. Schools also disseminate a culture of competition, gradation and values that are helpful to the capitalist economic system.

Agencies of Political Socialization

This brings us to the role of agencies of political socialization. If we take a broader view of political socialization, we see it takes place directly as well indirectly. Formal institutions of the state such as the state-owned or controlled media, school texts, legislators, executive and bureaucratic institutions, police and other order establishing agencies, political elites and political parties and informal agencies such as pressure, demand and protest groups, are involved in imparting various political information and direct political socialization.

Apart from communication and interaction with agencies of political socialization, some non-political agencies such as family and schools also impart direct political socialization. For example, familial attitude or disposition towards the political system, political parties and representatives can largely influence the orientation during childhood. Almond and Powell cite the example of Laurence Wylie's study, Village in the Vaucluse of a French town where he has shown how general attitude of contempt against the political system dominates children's attitudes.31 This is despite schools teaching on the contrary. Family can be a strong agency of imparting political attitudes directly. In fact, it can be argued that familial political disposition or orientation could serve as a strong means for continuity in party affiliations. Familial loyalty to a particular political party, to the Congress party or the Bhartiya Janata Party or a communist party amongst generations are not uncommon. V. O. Key, Jr in his study, Public Opinion and American Democracy explored the possibility of children disposed to consider themselves according to parental loyalty to Democrats and Republicans.32

The role of educational institutions in shaping political ideas and political orientation is obvious. At the direct level, there can be a course of civics telling students about political systems, their benefits and which political system to prefer and why. At various levels, students are exposed to simulated performance as legislators, bureaucrats, judges and such participants. At the latent level, values of competition, obedience, rigour of discipline, etc., influence political behaviour. Educational qualifications invariably affect the cognitive, affective and evaluative orientations. Education affects orientation of self as an active participant. An educated person may be more aware, more critical or attached and more evaluative or judgemental. An enlightened and educated middle class is considered as an important component of a successful democratic experience.

Experiences and behaviour learnt within peer and other in-groups (close social groups) also influence political views. Peer and intermediary influences on shaping of political views are also important in countries where citizenry includes those who are uneducated, peasantry and remotely settled. Shaping of public views and political opinion through third party political narration and information is a relevant in Indian villages. Though adio, newspapers and television are present, most of the political views and orientation in villages are shaped through third-party political narration. Third-party political narration implies discussion or communication about political issues and policies, programmes and leaders by relatively educated, informed and politically active persons or persons who are intermediaries between the people and the parties to those who are less informed, less educated and discerning and less connected with the media and politically active towns. Third-party political narration takes place at village tea shops, grocery and vegetable shops, weekly bazaars, marriage parties, muffasil towns, caste meetings, post-pooja or post-namaz sessions, or during the cultivation and irrigation. If one looks at the dynamics of village and rural political socialization in India, besides other agencies, the third-party political narration, provides a significant means.

Political socialization also takes place at the work place and in associational and professional interest groups. For example, trade unions are considered as an important agency of imparting political training to its members especially for demand and pressure orientation. Mass media influences the cognitive orientation by imparting information. It also provides a basis for affective and evaluative orientation. Open or controlled, mass media influences political beliefs and orientations.

Political Socialization or Hegemony and Cultural Reproduction

The role of various agencies of political socializsation is viewed in terms of their imparting a supportive political culture. However, some New Left theorists, Gramsci and Althusser view agencies of political socialization in a capitalist society necessarily as apparatuses of non-coercive domination and means of creating conditions favourable for maintenance of the capitalist system. In this, political socialization becomes a process of imbibing dominant culture and values, values and ideology that creates hegemony. Gramsci suggests that the domination in the capitalist system is maintained not only by force and coercion but also by hegemony. Hegemony is ideological domination created by various social, religious, educational and civil society institutions. Values, attitudes, orientations and feelings that agencies such as family, schools, mass media and religious institutions inculcate amongst the people are meant to reproduce the conditions that are necessary for maintenance of the capitalist system. These agencies in a way reproduce the conditions of capitalist production. Marx and Engels in The German Ideology have discussed about ‘bourgeois ideology’ that disguises and mystifies the class divisions and contradictions in a capitalist system. They called the ideas of ruling class as ruling ideas. Gramsci analyses how hegemony is generated by using ruling class ideas. Political socialization becomes an exercise in inculcation of ruling class ideas.

Civil society creates a context of hegemony with the help of educational, religious, intellectual and moral agencies—structures of legitimation. Organizations and institutions like family, schools, church, etc. provide the basic rules of behaviour, respect and moral deference to authority. With the help of educational, religious, familial and cultural means, hegemony is achieved. Hegemony stands for ‘intellectual, moral and political leadership and not merely economic domination.’33 Gramsci uses hegemony to define ‘the ability of a dominant class to exercise power by winning the consent of those it subjugates as an alternative to the use of coercion.’34 This can be achieved by inculcating dominant values and ideas, behaviour and political institutions as the values and ideas of all. Political socialization by helping individuals acquire, retain or change attitudes and behaviours that are appropriate to the interests of the dominant economic class is a process of reproducing dominance.

Pierre Bourdieu, a French sociologist and J. C. Passeron have applied the concept of cultural reproduction to analyse how dominant class imposes its cultural values as general values. Cultural reproduction refers to imposition of culture of the dominant class on society as legitimate. Pierre Bourdieu and J. C. Passeron in their study Reproduction: In Education, Society and Culture have analysed the phenomenon of cultural reproduction as a contrast to the process of political socialization. Legitimacy, hegemony, political socialization and cultural reproduction draw attention to the non-coercive elements in any system of domination.35 They help in maintaining and sustaining a system. On the other hand, it has been argued that in the erstwhile socialist societies of the USSR and the Eastern Europe with controlled media, institutions of education, communication and political participation, political socialization was carried out coercively and rigidly. One may also argue that during the socialist system, socialist values, feelings and attitudes were not internalized by the people but were only followed due to coercive fear. The proof of this is change in orientation and political behaviour in the aftermath of breakdown of the socialist system. It may be appropriate to note that Mao has given the theory of ‘permanent revolution’ meaning that there was a need for a continuous revolution to deal with ever-present contradictions in society.

Political socialization is a contested concept and has been associated with theorists who support the liberal–capitalist order. It has been criticized as means of reproducing domination. It is however, considered necessary for successful functioning of democracy through political training of the citizens to become active participants.

Political Culture as a Framework of Comparative Study

Political culture is understood, as subjective aspect of politics. Subjective aspect means beliefs, symbols and values, which people express towards political objects, institutions, process, etc. It defines the situation in which political action takes place.36 This means nature of the political process in different countries can be explained and understood with reference to how people think about politics, how and what demands they raise? Are they are supportive to the political system and structures and that too, whether in an individual capacity or as ethnic, tribal, religious and caste groups? While understanding the functioning of the political system and political process, political culture helps us understand the people's attitudes and orientation to political system. This is important because one gets to know the kinds of demands being made by the people, the way they are expressed and organized by the associational and interest groups, and coordinated and formulated in terms of policies and programmes by political parties or any such institution. If we look at the input-output flow of the political system, nature of inputs (demands, pressures, supports) would be crucial for the political system to decide on outputs (allocation, welfare, taxation, policies and programmes, etc.). Nature of inputs, both demands and supports, depends on what kind of political culture prevails. If we recall Weber's description of sources of legitimacy, support is based on traditional, charismatic and rational bases. In political culture also, nature of support will depend whether the political culture is characterized as parochial, subject or participant.

To study political systems in a comparative manner, political theorists have discussed about the scale of political development. While analysing roles, structures, input and output functions and political process, elements of differentiation, autonomy and secularization are applied. Almond and Powell's Comparative Politics: A Developmental Approach uses the criteria of sub-system autonomy and role specificity, structural and role differentiation and cultural secularization for comparing political systems. They call these ‘developmental variables. Absence or presence of these variables can be scaled and level of political development can be determined. Political culture provides a relevant entry point for such a study as relationship between structures, roles and orientations are relevant for comparing political systems. With the help of political culture, the nature of political process, roles, structures, demands and upward support flow and outputs and downward policy flow and nature of political participation can be known. Lucian Pye and Sidney Verba's study Political Culture and Political Development uses political culture for analysing political systems.

How political culture is geared to different types of roles and structures become relevant for comparative analysis. In some political systems, head of a tribal community may also officiate as chief in political matters. It may also happen that those who are head in tribal or social organization also become political representatives. Almond and Verba, citing James Coleman, says that this type of political culture is present amongst the African tribal societies and autonomous local communities.37 Due to intermixing of political, socio-religious and economic roles, it is said that the political aspect does not appear separate from the rest of the aspects of society. This is referred to as a lack of differentiation in roles and structures, or structural differentiation. This means there are no specialized roles for a legislator different from an executive or a judge and between interest and pressure groups from political parties. Further, there may not be separation between the religious head from that of a political head and decision on political and economic aspects are mixed with religious and social aspects. People are not oriented in terms of rational and empirical calculation and option analysis rather behave as per traditional or parochial relations. This indicates lack of cultural secularization. Neither are there autonomous structures for specialized functions. For example, in developed countries with a stable democratic set-up, the role of a political party is different from the role of a pressure group and the legislature from the judiciary. They also enjoy relative autonomy from each other. However, in parochial political culture there is lack of subsystem autonomy.

A developmental approach aims at comparing how different political systems progress on a graph of certain parameters such as sub-system autonomy, structural differentiation (e.g. pressure groups and political parties different, executive different from judiciary, etc.) and cultural secularization. Higher autonomy, differentiation and secularization mean the political system is highly developed. In their analysis, they have used political culture, political socialization, subcultures, lag between structural and cultural changes (e.g. introduction of adult suffrage on the basis of rational individual decision-maker as structural change but people still voting as caste, religious and ethnic groups), etc.

The concept of political culture as tool of analysis has been used by a host of theorists and analysts. Gabriel Almond and James Coleman's (eds) The Politics of Developing Areas, Gabriel Almond and Sidney Verba's The Civic Culture, Gabriel Almond and G. B. Powell's Comparative Politics: A Developmental Approach, Lucian Pye and Sidney Verba's (eds), Political Culture and Political Development, Gabriel Almond and Sidney Verba's (eds) The Civic Culture Revisited and Almond, Powell, Strom and Dalton's Comparative Politics Today apply the concept of political culture to the study of countries and functioning of political system. While Almond and Verba studied Britain, France, Germany, Mexico and USA; Almond, Powell, Strom and Dalton have analysed England, France, Germany, Japan, Russia, China, Mexico, Brazil, Egypt, India, Nigeria and the United States.

Applying the classification of political culture in terms of parochial, subject and participant or a combination of them, we can understand the nature and level of the following:

Sub-system autonomy