9. Connecting with an Audience

Most of what I have learned about communication and connection did not come from my speech and communication classes in school. My approach to public speaking has been shaped from my experience as a performer and from years of closely watching others perform. I worked my way through college playing drums in various jazz groups, beginning when I was 17. No matter how technically good the music was, I never saw a great live performance that lacked a solid connection between the performer(s) and the audience.

Playing music is a performance and also a presentation. Good presentations, like musical performances, are about sharing ideas and connecting on an intellectual and emotional level in an honest and sincere way.

The lesson I’ve learned from watching great live musical performances is that the music plus the artist’s ability to convey the (musical) message and connect with the audience is what it’s all about. If done well, the end result is far more than just the notes played. A true performance transcends the simple act of artists playing music and people listening. There are no politics and no walls. The music may touch the audience or it may not, but there is never even a hint of insincerity, questionable motives, or pretense of being anything other than what people see before them at that moment. The smiles, the heads nodding in agreement, and the feet tapping under the tables tell me that there is a connection, and that connection is no less than communication. It’s a fantastic feeling.

The art of musical performance and the art of presentation share the same essence in that the aim is about bridging the distance between the artist and audience to make a genuine connection. If there’s no connection, there can be no conversation. This is true whether you’re pitching a new technology, explaining a new medical treatment, or playing at Carnegie Hall.

A good tip to always remember: It’s not about us, it’s about them. And about the message.

Jazz, Zen, and the Art of Connection

There is a line of thinking that says if I tell you the meaning of Zen, then it wouldn’t really be Zen. The same could be said concerning the meaning of jazz. Of course, we can talk about them and label them. With our verbalization, we get close to the meanings—and the discussion may be interesting, helpful, and even inspiring. Yet we never experience the thing itself by talking about it. Zen is concerned with the thing itself. Zen is about the now—right here, right now. The essence of jazz expression is like this, too. It’s about this moment. No artificiality, no pretending to be anything you’re not. No acting. No wishing at this moment to be anywhere or with anyone except where you are.

While there are many forms of jazz, if you want to at least get close to the essence of the art, then listen to the 1959 album Kind of Blue by Miles Davis (Columbia). The liner notes for this classic album were written by the legendary Bill Evans, who plays piano on the recording. In these notes, Bill makes a direct reference to one of the Zen arts, sumi-e.

I always thought there was a sort of aesthetic to this album that expressed the tenets of restraint, simplicity, and naturalness—principles that are at the heart of the Presentation Zen approach as well. In the music you hear a free yet structured spontaneity, an idea that seems oxymoronic until you study one of the Zen arts—or jazz. A free yet structured spontaneity is exactly the kind of state we want to be in with an audience during a presentation.

You can establish better connections with an audience by bringing the spirit of jazz to your talk. By “spirit of jazz,” I mean the complete opposite of how people usually use the term jazz—as in “jazz it up,” that is, decorate it or add something on the surface. The spirit of jazz is about honest intention. If the intent is pure and the message clear, then that is all you can do. Jazz means removing the barriers and making it accessible, helping people to get your expression (your message, story, point). This does not necessarily mean you will always be direct, although this is often the clearest path. Hint and suggestion are powerful, too. The difference is that hint and suggestion with intent have a purpose and are done with the audience in mind. Hint and suggestion without intent or sincerity may result in simplistic, ineffective ramblings or obfuscation.

Jazz makes the complex simple through profound expressions of clarity and sincerity. It has structure and rules but also great freedom. Above all, jazz is natural. It is not about putting on a façade of sophistication or seriousness. In fact, humor and playfulness are also at the core of jazz. You may be a dedicated, serious musician or you may be an appreciative fan, but either way you also understand that to be human is to laugh and to play—play is natural to us and natural to the creative process. It’s only through our formal education that we begin to doubt the seriousness of play. When this happens, we begin to lose a bit of ourselves, including our confidence and a bit of our humanity. I’ve found through my parallel studies of jazz and the Zen arts that both have structure and practice at their core along with a strong component of playfulness and laughter—all elements we would like to bring to our presentations as well.

In most situations, you don’t need the latest technology or the best equipment in the world. Showing that you are well prepared and ready to present naked, with or without technology is far more important. Sincerity, honesty, and respect for the audience matter far more than technology and technique.

The Perfectly Imperfect Human Connection

To be human is to be imperfect. Today computers can generate music that sounds indistinguishable from music created by actual musicians, and studios have long been able to clean up even the tiniest imperfections in timing or pitch from recordings of actual musicians. What makes a live performance great is not the perfection of the music, however, but the humanity of the connection between musicians and audience.

Dave Grohl, the former drummer for Nirvana, is the founder, lead singer, and guitarist for the rock group Foo Fighters, a band with 11 Grammy Awards to date. Grohl often speaks about the power of the imperfect human element in good music. His words ring true for musical performance, and they apply to other arts such as public speaking and presentation. Here’s a bit of what he said when receiving a Grammy Award for Best Rock Performance in 2012:

“To me this award means a lot because it shows that the human element of making music is what’s most important. Singing into a microphone and learning to play an instrument and learning to do your craft, that’s the most important thing for people to do…. It’s not about being perfect, it’s not about sounding absolutely correct, it’s not about what goes on in a computer. It’s about what goes on in here [your heart] and what goes on in here [your head].”

Later Grohl clarified things in a press release stating that he is not anti-digital, but that his point is that the music is all about the imperfectly human element. “That thing that happens when a song speeds up slightly, or a vocal goes a little sharp,” Grohl says. “That thing that makes people sound like people. Somewhere along the line those things became ‘bad’ things, and with the great advances in digital recording technology over the years they became easily ‘fixed.’ The end result? In my humble opinion…a lot of music that sounds perfect, but lacks personality. The one thing that makes music so exciting in the first place.” In a sense, people are not attracted to the music because it’s perfect, their attracted to it because it’s not. People are attracted to you and your personality not because you are perfect, but because you are not.

All this talk of imperfection is not to suggest that you wing it or that you take a cavalier approach to presentation delivery. Yes, we prepare well and we aim for perfection as best we can in the moment, knowing full well that real perfection is not attainable. But if we strive for that which we may call perfect, we may just be able to achieve excellence. Salvador Dalí apparently used to say “Don’t be afraid of perfection. You’ll never attain it.” We will not attain it, but by aspiring toward it we may just attain a level of excellence that is a worthy contribution to the audience before us. And knowing that perfection is not actually possible helps us to relax a bit, which in fact helps us to be in the moment and that much closer to something approaching a perfectly imperfect but real human connection.

Opposite page: Dave Grohl performing live on stage with Foo Fighters.

Start Strong to Make a Connection

To establish a connection with an audience, we must grab their attention right from the start. Granville N. Toogood, author of The Articulate Executive, also emphasizes starting off quickly and beginning with punch. “To make sure you don’t get off on the wrong foot, plunge right in,” he says. “To galvanize the mind of the audience, you’ve got to strike quickly.” I always urge people not to waste time with formalities, such as long introductions or filler that is not related to the presentation’s goal. The beginning is the most important part. You need an opening that grabs people and brings them in. If you fail to hook them at the start, the rest of your presentation may be for naught.

The primacy effect in the context of presentations suggests that we remember more strongly what happens at the beginning of a presentation. There are many ways to strike quickly and start with punch to make a strong initial connection. In my book The Naked Presenter (New Riders), I introduced the idea of making a strong connection by incorporating into your opening content that which is personal, unexpected, novel, challenging, or humorous. Not coincidentally, these elements comprise the acronym PUNCH to help you remember. Most of the best presentations contain at least one of these elements. Let’s take a look at PUNCH in more detail.

Personal

Make it personal. Personal in this case does not mean a long self-introduction about your background complete with organizational charts or why you are qualified to speak. A personal and relevant story, however, can be a very effective opening so long as it illustrates a key engaging point or sets the theme in a memorable way.

Unexpected

Reveal something unexpected. Do or say something that goes against what people expect to get their attention, and taps into the emotion of surprise. This emotion increases alertness and gets people to focus. “There must be surprise…some key facts that are not commonly known or are counterintuitive,” says management guru Tom Peters. “No reason to do the presentation in the first place if there are no surprises.”

Novel

Show or tell something novel. Get people’s attention by introducing something new. Start with a powerful image that’s never been seen, reveal a relevant short story that’s never been heard, or show a statistic from a brand-new study that gives new insights into a problem. Chances are your audience is filled with natural-born explorers who crave discovery and are attracted to the new and the unknown. Novelty is threatening for some people, but assuming the environment is safe and there is not an overabundance of novelty in the environment, your audience will be seeking the novel and new.

Challenging

Challenge conventional wisdom or the audience’s assumptions. Consider challenging people’s imaginations, too: “How would you like to fly from New York to Tokyo in two hours? Impossible? Well, some experts think it’s possible!” Challenge people intellectually by asking provocative questions that make them think. Many presentations fail because they simply attempt to transfer information from speaker to listener as if the listeners were not active participants.

Humorous

Use humor to connect with the audience through a shared laugh. There are many benefits to laughter. Laughter is contagious. An audience that shares a laugh becomes more connected with each other and with you, creating a positive vibe in the room. Laughter releases endorphins, relaxes the whole body, and can even change one’s perspective. The old adage is “if they are laughing, they are listening.” This is true, although it does not necessarily mean they are learning. It is critical, however, that the humor be directly relevant to the topic at hand or otherwise fit harmoniously into the flow of the narrative without distracting you from the objective of your talk.

The concept of recommending humor in a presentation gets a bad rap because of the tired practice of opening a speech with a joke, almost always a lame one. But I’m not talking about telling jokes. I’m suggesting that an observation of irony, an anecdote, or a short humorous story that makes a relevant point or introduces the topic and sets the theme are the kinds of openings that can work.

There are many ways to start a presentation, but no matter how you choose to start, do not waste those initial valuable two or three minutes “warming up” the audience with filler material or formalities. Start strong. The five elements comprising PUNCH are not the only options to consider, but if your opening contains at least one of these approaches, then you are on your way to opening with impact and making a strong connection.

The Honeymoon Period

Getting and keeping an audience’s attention can be a tricky thing. Generally, audiences want you to succeed, but they will still only give you one or two minutes of a “honeymoon period” for you to make a good impression. Even famous, well-established presenters, including celebrities, will only get about a minute before audiences grow tired of a presenter’s inability to make a good impression and grab their attention. There is no excuse for a weak start. If your technology lets you down just as your presentation starts, you cannot stop. As they say in show business: “The show must go on.” People form impressions of you and the presentation in the first few moments. You never want those first few moments to be a memory of you trying to get the technology to work.

Never Start with an Apology

Do not apologize or imply that you have not prepared enough for a given audience. It may be true, and your apology may be sincere and honest (rather than just being an excuse), but it never comes across well to an audience. The audience does not need to know that we have not prepared as much as we would have liked, so why mention it and get it in their head? You actually may be prepared enough and doing well, but now the audiences is saying to themselves “Man, he’s right—he didn’t prepare enough.” The same goes for telling people you’re nervous. “You didn’t look nervous, but now that you mention it….”

A confession that you are nervous may seem honest and transparent, but it is too self-focused at a time when you are supposed to be focused on the audience and their needs and their feelings. An admission about being nervous is not said to make the audience feel better, only to make yourself feel better. If you admit that you are nervous, you may actually feel better since labeling and acknowledging your emotion is better than suppressing it. This is why people say it—because saying it out loud does make you feel a little better. However, the presentation is about the audience, and telling them how nervous you are does not serve their interest. Acknowledge to yourself that you are nervous. Being nervous is normal and saying it to yourself will help you feel better. But you do not need to share this information with the audience.

Do You Need to Show the Structure?

Usually—unless you’re leading a long seminar—you do not need to display a visual agenda for your presentation. But remember, during the preparation stage, you built your presentation on a simple structure. The audience need not be aware of your structure, but without it you could not have crafted a compelling narrative that takes your audience someplace. In the book Conversations with the Great Moviemakers of Hollywood’s Golden Age at the American Film Institute (Vintage, 2007) by George Stevens Jr., the legendary filmmaker Billy Wilder stresses the importance of structure while describing the plot points in the classic film Some Like it Hot (shown in slide below).

Project Yourself

To make a connection you cannot be timid—you must project yourself. There are three things to consider when evaluating your ability to project yourself to an audience aside from the content of the talk: The way you look, the way you move, and the way you sound. The audience members, whether they know it or not, are judging you and your message based on these elements. All these factors influence your ability to make a strong connection.

Look the Part

How you dress matters. A rule of thumb is to dress at least a little more formally than your audience. It’s important to dress appropriate to the organization and the occasion, of course, but it’s better to be a bit overdressed than underdressed. You want to project an image of professionalism, but you do not want to seem out of touch with your audience either. In Silicon Valley, for example, the dress code can be quite casual and even a well-groomed person in jeans with a quality shirt and a good pair of shoes may look professional. (When we occasionally saw people in business suits on the Apple campus, we could tell they were from out of town.) In Tokyo, both men and women cannot go wrong with a dark business suit virtually anywhere. You can always bring your formality down a notch by removing your jacket, removing the tie, and rolling up the sleeves, but it’s difficult to dress up a look that is too casual. To be safe, and to show respect for your audience, err on the side of dressing up.

Move with Purpose

If you can avoid it, do not stand in one place during the entire presentation. It’s far better to walk to different parts of the stage or room, which allows you to engage with more people. You should not, however, pace back and forth or wander around the area near the screen without purpose. This kind of movement is distracting and projects a nervous energy rather than a confident, open energy. When you walk from one area to another, do so slowly and while standing tall. Stop to make your point or tell a story, then move slowly to another part of the stage before stopping again to elaborate on a different point. When someone asks a question from the opposite side of the room, walk slowly in their direction, acknowledging their presence while listening and approaching their side of the room. When you stand, do so with your feet comfortably but firmly planted about shoulder-width apart. You should not stand like a cowboy about ready to draw his guns, but neither should you stand with your feet together as if standing at attention. Standing at attention or with your legs crossed demonstrates a closed, defensive, or uncertain attitude. These positions, which are unnatural ways to stand when we are relaxed, make you a bit unstable and project weakness to others. About the only thing worse than standing on a stage with your legs crossed is doing so while leaning against the lectern. At best, it looks sloppy. At worst, it projects an image of weakness.

When we get nervous, most of us tend to speed up our movements, including hand gestures. If you want to project a more calm, relaxed, and natural image to the audience, remind yourself to slow everything down.

Face the Audience

If you are projecting visuals behind you, there is little need to turn your head to look back. Even if you gesture toward the screen, stand so that your shoulders are facing in the direction of the audience. If you keep your shoulders pointed toward the front, you will naturally turn your head back toward the audience without thinking about it after you glance or point at the screen. Turning slightly and briefly toward the screen to point out a detail is acceptable. However, continually looking at the screen as a reminder of where you are is very distracting and unnecessary. Except in rare incidents, if you use a computer to project visuals, you can place the computer down low in front of you—as I did for this college lecture pictured below—so there is little reason to turn around.

Connect with Eye Contact

Related to the importance of facing the audience is establishing good eye contact. Maintaining natural eye contact with the audience is crucial, which is one of the reasons I advise against reading a script or relying on notes—it’s hard to look into people’s eyes when your eyes are looking down at notes. Your eye contact should appear natural, and you achieve this by looking at actual people in the room. If you instead gaze out at the back of the room or to a point on either side of the room, your audience will detect this at some level and the connection will be weakened.

If your audience is relatively small, say, under 50 or so, it may be possible to actually look everyone in the eye at some point during your talk as you move deliberately to different parts of the room. For larger audiences in a typical keynote-style presentation, it is still useful to pick out actual people to lock eyes with as you speak—even people who are sitting toward the back. By looking at one person, others near that person will feel as if you are looking at them as well. It is important not to just glance at or scan general areas of a room but rather to briefly establish actual eye contact with people in different parts of the room. We certainly do not want to have our eyes looking down at the computer or have our eyes fixed on the screen, as demonstrated in the first two photos below.

The first two images above show exactly what not to do to maintain good eye contact. Two of the most common mistakes inexperienced presenters make are (1) hiding behind their computer and looking down at the screen, or (2) if they do get close to their projected screen, they glue their eyes in the direction of the slides instead of the audience. The example on the lower left is more like it. The audience can see the speaker and the visuals in the same field of view and the presenter can create a better connection with the audience.

(1) It is acceptable to briefly turn your head toward the screen as you point to a particular element in the slide, while keeping your body facing toward the audience for the most part.

(2) However, you should not allow your gaze to linger on the slide but instead re-establish eye contact with the audience even as your hand continues pointing.

(3) Because you did not turn your entire body in the direction of the screen, when you drop your hand, you will once again be facing the audience naturally.

Looking down at your smartphone has virtually become the international gesture for “I am somewhere else at the moment.” Presenters usually don’t like it when audience members look repeatedly at their phones, and it is not a good look for presenters either. Sometimes notes are necessary, though we try to avoid it if possible. Still, the small screen makes a smartphone awkward to use and even less scannable than a simple piece of paper. But I am old school, so maybe I’m just out of touch. So, I asked about 100 of my college students, and the overwhelming majority said that they do not like to see speakers using smartphones for notes while presenting.

Put Energy in Your Voice

It’s true that the best presentations seem more like good conversations, but there is a difference between speaking with two or three people over coffee and standing to present to an auditorium of 500 people after lunch. Your tone should be conversational, but your energy must be cranked up several notches. If you are enthusiastic, the energy will help project your voice. Mumbling is absolutely not permitted, and neither is shouting. Shouting is usually not sustainable, and it’s very unpleasant for the audience. When you shout, the volume may go up but the richness of your voice, the peaks and valleys of your unique intonation, are lost. So stand tall, speak up, and articulate clearly, but be careful not to let your speaking evolve into shouting as you speak with energy and project your voice.

Should you use a microphone? If your room is a regular-sized classroom or conference room with space for only 10 to 30 people, then a mic may not be necessary. But in almost every other case, a mic is a good idea. Remember, it is not about you, it is about them. Giving the audience even just a slight bump in your volume through the use of a mic will make it easier for them to hear you. Many presenters, especially men, eschew a microphone and decide to shout instead. It’s as if declining a mic and choosing to shout is somehow more manly and assertive. But unless you are a head coach delivering an inspiring halftime speech for your football team, shouting is a very bad idea. You are not addressing your troops, remember, you are trying to present in a natural, conversational manner. The microphone, far from being a barrier to connection, can actually be a great enabler of intimacy as it allows you to project in your best and most engaging natural voice.

Only use a handheld mic, however, for very short speeches and announcements. A better option than a handheld mic is a wireless lavalier mic, also called a clip-on or lapel mic. The lavalier is good because it frees up a hand, which is especially important if your other hand is holding a remote control device. The downside of a lavalier is that if you turn your head to the side, some mics will not pick up your voice as well. Whenever possible, the best type of microphone to use is the headband or headset variety used for conferences such as TED. This type of wireless mic places the tiny tip of the mic just to the side of your mouth or your cheek and is virtually invisible to the audience. The advantage of this mic, besides eliminating the possibility of ruffling noises from your shirt, is that no matter how you move your head, the mic stays in the same position and always picks up your voice clearly.

Founder and Executive Producer for TEDxKyoto Professor Jay Klaphake addresses the crowd at TEDxKyoto, 2018. The nearly invisible wireless headset mic picks up his voice well and allows for freedom of movement. (Photo by Neil Murphy, courtesy of TEDxKyoto.)

Avoid Reading a Speech

Communications guru Bert Decker urges speakers to avoid reading a speech whenever possible. In his book You’ve Got to Be Believed to Be Heard (St. Martin’s Press), Decker advises against reading speeches. “Reading is boring,” he says. “Worse, reading a speech makes the speaker look inauthentic and unenthusiastic.” This goes for reading slides as well. Many years ago, the typical use of slideware involved people actually reading lines of text right from the slides behind them—and believe it or not, it still happens today. But don’t do it. Putting lots of text on a slide and then reading that text is a great way to alienate your audience and ruin any hope you have of making a connection.

Guy Kawasaki, a venture capitalist and former chief evangelist at Apple, urges people to use large type on slides that the audience can actually see. “This forces you,” he says, “to actually know your presentation and just put the core of the text on your slide.” This is what the outspoken Kawasaki had to say about reading text off slides in a speech he gave to a room full of entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley in 2006:

“If you need to put eight-point or ten-point fonts up there, it’s because you do not know your material. If you start reading your material because you do not know your material, the audience is very quickly going to think that you are a bozo. They are going to say to themselves ‘This bozo is reading his slides. I can read faster than this bozo can speak. I will just read ahead.’”

Guy’s comments got a lot of laughs, but he’s right. If you plan on reading slides, you might as well call off the presentation now, because your ability to connect with, persuade, or teach the audience anything will approach zero. Reading slides is no way to show presence, make a connection, or even transfer information in a memorable way. In many cases, reading a deck of slides is, however, a good way to put the room to sleep.

If Your Idea is Worth Spreading…

The TED website is a great resource. All of the presentations available on the site have subtitles available for each video in many different languages. Transcripts in several different languages are also available.

There are many fantastic TEDx events all over the world, and TED hosts the videos from those events on the TED website.

The annual TED (Technology, Entertainment, Design) conference brings together the world’s most fascinating thinkers and doers, who are invited to give talks on stage in 18 minutes or less. The time limit usually results in very concise, tight, and focused talks. If you have ideas worth talking about, then you’ve got to be able to stand, deliver, and make your case. As the presenters at TED demonstrate every year, presentation skill is critically important.

What’s great about TED is that their amazing presentations are not limited to an elite few. Instead, they “give it away” by uploading tons of their best presentations to the Web and making the videos available in many different formats for online viewing and downloading. Hundreds of quality short-form presentations from the TED archives are available online, and more are added each week. The production quality is excellent and so is the content. TED truly exemplifies the spirit of the conceptual age—share, give it away, make it easy—because the more people who know your idea, the more powerful it becomes. Because of the high-quality free videos, the reach and impact of TED is huge. The TED website is a great resource for content and for those interested in watching good presentations, often with good use of multimedia.

Hans Rosling: Doctor, Professor, and Presenter Extraordinaire

Hans Rosling was a professor of global health at Sweden’s Karolinska Institute, and the Zen master of presenting statistics that have meaning and tell a story. Dr. Rosling co-developed the software behind his visualizations through his nonprofit Gapminder. Using U.N. statistics, Rosling showed that the world has seen transformative changes in recent years—it is indeed a different world. Several presentations on the TED website showcase Rosling’s talents. Conventional wisdom says to never stand between the screen and the projector, which is generally good advice. But as you can see from the photo here, Rosling at times defied conventional wisdom and got involved with the data in an energetic way that engaged his audience with the data, its meaning, and the big picture.

Sadly, Professor Rosling died on September 7, 2017 in Uppsala, Sweden. He was just 68. Professor Rosling’s passing was a profoundly mournful day for his family and anyone who knew him, obviously. But it was also a sad day for all of us in the greater TED community and the data visualization/business intelligence communities as well. Dr. Rosling’s work had been seen by millions and will continue to be seen by millions more worldwide. It is incalculable just how many professionals Dr. Rosling inspired over the years. His presentations, always delivered with honesty, integrity, and clarity, were aided by clear visuals of both the digital and analog variety. He was a master statistician, physician, and academic, but also a superb presenter and storyteller.

Dr. Rosling’s vision lives on through the work of his son, Ola Rosling, and Ola’s wife Anna R. Rönnlund, who continue to keep the dream of a more fact-based, rational worldview alive at Gapminder.org. Gapminder is an incredible resource.

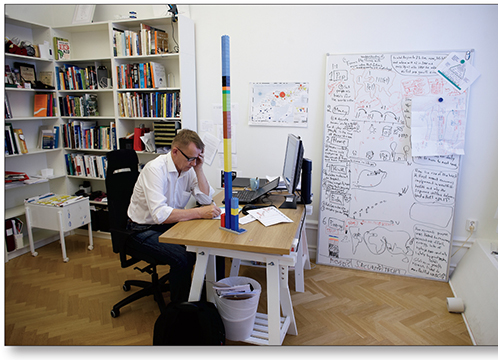

Dr. Hans Rosling’s passionate, unconventional relationship with data enlivened his presentations. (Photo by Stefan Nilsson.)

Dr. Hans Rosling was equally at home using analog and digital visuals in preparing his talks. (Photo by Jörgen Hildebrandt.)

Hara Hachi Bu: Why Length Matters

A consequence of Zen practice is increased attentiveness to the present, a calmness, and an ability to focus on the here and now. However, for your average audience member, it is a safe bet that he or she is not completely calm or present in the here and now. Instead, your audience member is processing many emotional opinions and juggling several issues at the moment—both professional and personal—while doing his or her best to listen to you. We all struggle with this. It is virtually impossible for our audiences to concentrate completely on what we are saying, even for shorter presentations. Many studies show that concentration really takes a hit after 15 to 20 minutes. My experience tells me it’s less than that. For example, CEOs have notoriously short attention spans while listening to a presentation. So the length of your presentation matters.

Every case is different, but generally, shorter is better. But why then do so many presenters go past their allotted time—or, worse, milk a presentation to stretch it out to the allotted time, even when it seems that the points have pretty much been made? This is probably a result of much of our formal education. I can still hear my college philosophy professor saying before the two-hour in-class written exam: “Remember, more is better.” As students, we grow up in an atmosphere that perpetuates the idea that a 20-page paper will likely get a higher grade than a 10-page paper, and a one-hour presentation with 25 presentation slides filled with 12-point lines of text shows more hard work than a 30-minute presentation with 50 highly visual slides. This old-school thinking does not take into account the creativity, intellect, and forethought that it takes to achieve a clarity of ideas. We take this “more is better” thinking with us into our professional lives.

One Secret to a Healthy Life (and a Great Presentation)

The Japanese have a great expression concerning healthy eating habits: hara hachi bu, which means “eat until 80 percent full.” This is excellent advice, and it’s pretty easy to follow this principle in Japan because portions are generally much smaller than in such places as the United States. Using chopsticks also makes it easier to avoid shoveling food in and encourages a bit slower pace. In Japan and Asia in general, we usually order as a group and then take only what we need from the shared bounty. I have found—ironically, perhaps—that if I stop eating before getting full, I am more satisfied with the meal. I’m not sleepy after lunch or dinner, and I generally feel much better.

The principle of hara hachi bu also applies to the length of speeches, presentations, and even meetings. My advice is this: No matter how much time you are given, never ever go over your allotted time; in fact, finish a bit before your time is up. How long you talk will depend on your unique situation at the time, but try to shoot for 90 to 95 percent of your allotted time. No one will complain if you finish with a few minutes to spare. The problem with most presentations is that they are too long, not that they are too short.

Leave Them Just a Little Hungry (for More)

Professional entertainers know that you want to end on a high note and leave the audience yearning for more from you. We want to leave our audiences satisfied—motivated, inspired, more knowledgeable—not feeling that they could have done with just a little less.

We can apply this spirit to the length and amount of material we put into presentations as well. Give them high quality, but do not give them so much quantity that you leave them with their heads spinning and guts aching.

This slide shows the contents of a typical ekiben (a special boxed meal sold at train stations) from one of my trips to Tokyo. Simple. Appealing. Economic in scale. Nothing superfluous. Made with the honorable passenger in mind. After spending 20 or 30 minutes savoring the contents of the ekiben, I’m left happy, nourished, and satisfied, but not full. I could eat more—another perhaps—but I do not need to. Indeed, I do not want to. I am satisfied with the experience. Eating to the point of becoming full would only destroy the quality of the experience.

Every word that is unnecessary only pours over the side of a brimming mind.

—Cicero

In Sum

You need solid content and logical structure, but you also have to make a connection with the audience. You must appeal to both the logical and the emotional sides of your audience members.

If your content is worth talking about, then bring energy and passion to your delivery. Every situation is different, but there is never an excuse to be dull.

Don’t hold back. If you have a passion for your topic, then let people know it.

Make a strong start with PUNCH. Include content that is personal, unexpected, novel, challenging, or humorous to make a connection from the beginning.

Project yourself well by dressing the part, moving with confidence and purpose, maintaining good eye contact, and speaking in a conversational style but with elevated energy.

Try not to read a presentation or rely on notes.

Remember the concept of hara hachi bu. It is better to leave your audience satisfied yet yearning for a bit more, than to leave them stuffed and feeling that they have had more than enough.