3. Planning Analog

The most important thing you can do in the initial stage of preparing for your presentation is to get away from your computer. A fundamental mistake people make is spending almost the entire time thinking about their talk and preparing their content while sitting in front of a computer screen. Before you design your presentation, you need to see the big picture and identify a single core message or messages. This can be difficult unless you create a stillness of mind for yourself, something that is hard to do while puttering around in slideware on your device or getting distracted by social media.

Although software makers encourage you to plan your presentations with their tools, I don’t recommend it. In fact, the software makers encourage this, but I don’t recommend it. There is something powerful and natural about using paper and pen to sketch out rough ideas in the analog world that leads to more clarity and better, more creative results when we finally get down to representing our ideas digitally. Because your presentation will be accompanied by multimedia, you will be spending plenty of time in front of a computer or other digital device later. I call preparing the presentation away from technology going analog, as opposed to going digital at the computer.

Slowing Down to See

Slowing down is not just good advice for a healthier, happier, more fulfilling life, but it’s also a practice that leads to greater clarity. Your instinct may be to say this is ridiculous—business is all about speed. First to innovate. First to market. First and fast.

What I am talking about here, however, is a state of mind. You have many things on your plate, no doubt. You are busy. But busy is not really the problem. Yes, there never seems to be enough time in the day to do things the way you would prefer to do them, and we all face time constraints. But time constraints can also be a great motivator, bringing a sense of urgency that stimulates creative thinking and the discovery of solutions to problems. The problem today, though, is not “busy” but “busyness.”

Busyness is that uncomfortable feeling you have of being rushed, distracted, and a bit unfocused and preoccupied. Although you may be accomplishing tasks, you wish you could do better. You know you can. But in spite of your best intentions, you find it difficult to create a state of mind that is contemplative rather than reactionary. You try. You take a deep breath. You begin to think about the big presentation next week. So you launch your application and begin to think. Then the office phone rings, but you let it go to voicemail because your boss is calling you on your smartphone at the same time. “Need TPS reports ASAP!” she says. Then your e-mail notifies you that you’ve got new messages, including one from your biggest client with the subject line “Urgent! TPS reports missing!!!” Then your coworker pops his head in the door, “Hey, did you hear about the missing TPS reports?” So you get to work reacting and putting out fires. In this sort of environment, it’s nearly impossible to slow down.

Busyness kills creativity. Busyness leads to the creation and display of a lot of cluttered presentation visuals that substitute for engaging, informative, and provocative meetings, seminars, or keynote speeches where actual conversations could and should be taking place. But people feel rushed, even frantic. So they slap together some slides from past presentations and head off to their next presentation. Communication suffers…the audience suffers. Yes, we’re all insanely busy—professionals and students both—but this is all the more reason we owe it to ourselves and our audiences not to waste time with perfunctory “slideshows from hell.” To do something better takes a different mindset, and it takes time and space away from busyness.

When you think about it, the really great creatives—designers, musicians, even entrepreneurs, programmers, etc.—are the ones who see things differently and who have unique insights, perspectives, and questions. (Answers are important, but first come questions.) For many of us, this special insight and knowledge, as well as plain ol’ gut feeling and intuition, can come about only when we slow down, stop, and see all sides of our particular issue. It does not matter if you are a scientist, engineer, medical doctor, or businessperson. When you prepare a presentation, you are a creative, and you need time away from technology and dealing with digital outlines and slides. And whenever possible, you also need time alone.

One reason many presentations are so ineffective is that people today just do not take—or do not have—enough time to step back and really assess what is important and what is not. They often fail to bring anything unique, creative, or new to the presentation. This is not because they are not smart or creative beings. Often, it is because they did not have the time alone to slow down and contemplate the problem. Seeing the big picture and finding your core message may take some time alone off the grid. There are many ways to find solitude, and you don’t even have to be alone. I find a pleasant form of solitude, for example, at cafés in Osaka, Nara, and Kyoto where the friendly staff know me by name. These are bustling cafés but also cozy and relaxing with loads of overstuffed sofas and chairs and jazz playing softly in the background. And I am left alone.

I’m not suggesting that more time alone is a panacea for a lack of ideas or that it necessarily leads to more creativity or better solutions. But I think you will be pleasantly surprised if you can create more time every day, week, month, and year to experience solitude. For me, solitude helps achieve greater focus and clarity while also allowing me to see the big picture. Clarity and the big picture are the fundamental elements missing from most presentations.

I don’t want to overly romanticize solitude. Too much alone time obviously can be a bad thing as well, yet in today’s busy world, too much solitude is a problem faced by few of us. For most professionals, finding some time alone can be a great struggle indeed.

The Need for Solitude

Many believe solitude is a basic human need, and to deny it is unhealthy for both mind and body. Dr. Ester Buchholz, a psychoanalyst and clinical psychologist who passed away in 2004 at the age of 71, did quite a bit of research on solitude during her career—she called it “alone time.” Dr. Buchholz thought society undervalued solitude and alone time and overvalued attachment. Dr. Buchholz thought periods of solitude were important if we were to tap our creative potential. “Life’s creative solutions require alone time,” she said. “Solitude is required for the unconscious to process and unravel problems.” The second half of Dr. Buchholz’s quote appears in the slide below, a slide I have used in some of my talks on creativity.

(Image in slide from Pearson Asset Library.)

Forest Bathing

We live in an area of Nara, Japan that is surrounded by forests. I have made it a practice to jog or just take long walks in the forests that surround our town. If I’m preparing for a big presentation or another project that I am worried about, I take a tiny digital voice recorder along in my pocket. I don’t try to think on the problem; I just walk among the trees. But when ideas do materialize that I think are worth remembering, I can easily record the thoughts verbally. This device is invaluable and takes the pressure off having to remember my ideas and insights. I could use my smartphone for this, but digital voice recorders are much smaller and lighter, and more importantly, the tiny devices do not have the myriad distractions that a smartphone possesses.

I have always loved time in nature, but it was only since I wrote the first edition of this book in 2008, that I discovered the idea of shinrin-yoku or “forest bathing.” In Chinese characters, shinrin-yoku is written 森林浴, the three characters representing forest, woods, and bath. Forest bathing is sometimes referred to as forest therapy as well, because there are real therapeutic benefits to the act of spending significant periods of time in natural wooded areas.

It is only since the 1980s that the term shinrin-yoku has been in use. Research into the possible connection between forests and human health began in earnest by Dr. Qing Li and others at the Nippon Medical School in Tokyo in the early 2000s. Dr. Qing Li is one of the world’s leading experts on shinrin-yoku and is currently Associate Professor of the Nippon Medical School in Tokyo. Dr. Li has been studying the effects of forest environments on human health and well-being for over 30 years and has published many scientific papers in the field of forest medicine.

I recommend Dr. Li’s book published in April of 2018 called Forest Bathing: How Trees Can Help You Find Health and Happiness (Penguin Life). This book is a good introduction to shinrin-yoku. “Forest-bathing can help you sleep and it can put you in a better mood,” Dr. Li explains. “It lowers your heart rate and your blood pressure and improves cardiovascular and metabolic health. And most importantly, it can boost your immune system.”

Research on the effects of forested environments on mental health and well-being supports the idea that time spent walking in forests helps us clear our minds, think more clearly, as well as improve memory and problem-solving abilities. The literature on forest bathing also supports improved creativity as a consequence of time spent in among trees. Citing research from the universities of Utah and Kansas, Dr. Li says that “spending time in nature can boost problem-solving ability and creativity by 50 percent.”

One of the easiest things you can do to calm your mind, improve your mood, and increase your creativity is to spend time in the forest. This claim is backed up by research, but we know this intuitively and from our own experience. And yet, most professionals, and students too, spend increasing amounts of their time indoors. We should be doing less of that and spending more time in nature. So, if you are stuck on a problem—a presentation or anything else—go for a long walk in the forest. If you do not have a forest, then a city park with an abundance of nature may do the trick.

A Bike or a Car?

Software companies have oversold us on the idea of following templates and wizards, which while sometimes useful, often take us places we do not really want to go. In this sense, visual design expert Edward Tufte is right when he says there is a cognitive style to Microsoft PowerPoint that leads to an oversimplification of our content and obfuscation of our message (The Cognitive Style of PowerPoint, Graphics Press). The same could be said of other presentation apps as well. Presentation software applications are wonderful for displaying media in support of our talks, but if we are not careful, these applications also lead us down a path adorned with bells and whistles that may distract more than they help.

More than 35 years ago, Steve Jobs and others in Silicon Valley were talking about the remarkable potential of personal computers and how these tools should be designed and used in a way that enhanced the great potential that exists within each of us. Here’s what Steve Jobs said back then in a documentary called Memory and Imagination (Michael Lawrence Films):

“What a computer is to me is that it’s the most remarkable tool that we’ve ever come up with, and it’s the equivalent of a bicycle for our minds.”

—Steve Jobs

When it comes to locomotion, humans are not as efficient as other animals, Jobs said. But a human on a bicycle is the most efficient animal on the planet. The bicycle amplifies our input in an enormously productive way. Isn’t this what a computer—the most magnificent tool of our time—should do?

During the planning stages of a presentation, does your computer function as a bicycle for your mind, amplifying your own capabilities and ideas? Or is it more like a car for your mind with prepackaged formulas that make your ideas soft? Your mind benefits when you use the computer like a bike, but it loses out when you rely on technology’s power the way you rely on your car’s power.

It’s important to understand the principles of presentation creation and design, and not merely follow software applications’ rules. The best software does not so much point the way as it gets out of the way, helping us to amplify our own ideas and abilities. One way to ensure that your technology and your software applications remain great tools of amplification for your ideas and your presentation is to first turn off the tech and walk away from it. You’ll be back soon enough.

Paper, a Whiteboard, Post-it Notes, or a Stick in the Sand

My favorite tools for preparing a presentation (or any other project for that matter) usually consist of a large notebook or storyboard journal and a few colored pens. If I am in my office, then the whiteboard is my tool of choice. As wonderful as digital technology is, I don’t think anything is as quick, easy, and immediate as a simple pad and pencil, and nothing gives me space to jot down ideas quite like a large whiteboard.

Too many people do all the work on their presentations in slideware. In this regard, we can learn a lot from professional designers. Most professional designers—even young, new media designers who’ve grown up on computers—usually do much of their planning and brainstorming on paper or a whiteboard.

This became very clear to me many years ago when I was still working at Apple Computer, Inc. One day, I visited a senior director on one of the creative teams across the Apple campus to get his input on a project. He said he had sketched out a lot of ideas to show me, ideas he’d shared already with Steve Jobs days before. I assumed that he had prepared some slides or a movie or, at least, had printed out some color images in Adobe Illustrator or Adobe Photoshop to show me. But when I arrived at his office, I found that the beautiful Apple Cinema Display on his desk was off. (I learned later that this talented creative director worked for days without ever turning on his Mac.) Instead, he had sketched out his ideas on a scroll of white paper that stretched about five meters across his office wall. This large scroll was a combination of hand-drawn images and text resembling a large comic strip. The creative director started at one end of the strip and walked me through his ideas, stopping occasionally to add a word or graphic element. After our meeting, he rolled up his sketches and said “take ’em with you.” Later, I would incorporate his ideas into our internal presentation.

“If you have the ideas, you can do a lot without machinery. Once you have those ideas, the machinery starts working for you…. Most ideas you can do pretty darn well with a stick in the sand.”

—Alan Kay

(Interview in Electronic Learning, April 1994)

Pen and Paper

I spend a lot of time working outside my office in coffee shops, in parks, and while riding on the Japanese Bullet Train (Shinkansen) on my trips to Tokyo. And although I have a MacBook Air or iPad with me at virtually all times, it is pen and paper that I use to privately brainstorm, explore possibilities, make lists, and generally sketch out my ideas. I could use the computer, but I find—as many do—that the act of holding a pen in my hand to sketch out thoughts seems to create a more immediate, more natural connection to my so-called right brain and encourages a more spontaneous flow and rhythm for visualizing and recording ideas. Compared to working with a keyboard, the act of using paper and pen to explore ideas and to make those ideas visible seems far more powerful. It’s certainly simple.

Whiteboards

I often use a large whiteboard in my office or at my home to sketch out my ideas. The whiteboard works for me because I feel uninhibited and free to brainstorm and sketch ideas on a bigger scale. I can also step back (literally) and imagine how my presentation might flow logically when slides are added later. The advantage of a whiteboard is that you can use it with small groups to record concepts and directions. As I write down key points and assemble an outline and structure, I can draw quick ideas for visuals, such as charts or photos that will later appear in the slides. I draw sample images that I can use to support a particular point, say, a pie chart here, a photo there, perhaps a line graph in this section, and so on.

You may be thinking that this is a waste of time: Why not just go into software and create your images there so you do not have to do it twice? Well, the fact is, if I tried to create a storyboard first on the computer, it would actually take longer, as I would constantly have to go from normal view to slide sorter view to see the whole picture. The analog approach (paper or whiteboard) to sketching out my ideas and creating a rough storyboard really helps solidify and simplify my message in my own head. I then have a far easier time laying out those ideas in one of the many presentation applications that are available, including PowerPoint. I usually do not even have to look at the whiteboard or legal pad when I am on the computer because the analog process itself gave me a clear image of how I want the content to flow. I glance at my notes for reminders about the visuals I thought of using at certain points and then go to one of the stock image websites or to my own library of photos to find the perfect image.

Post-it Notes

Large sheets of paper and marking pens—as old school as they may seem—can be wonderful, simple tools for initially sketching out your ideas and recording the ideas of others. Back in my Silicon Valley days, I sometimes led brainstorming sessions by sticking large Post-its on the wall. I wrote ideas down or others stepped up to the front and sketched out their ideas the old-fashioned way while arguing their point or elaborating on others’ thoughts. It was messy, but it was a good mess. By the end of the session, the walls were filled with large Post-its, which I then took back to my office and stuck on my own walls. As we developed the structure and visuals for the presentation, we often referred to the sheets on the walls, which were on display for days or weeks. Having the content on the walls made it easier to see the big picture. It also made it easier to see what items could be cut and which were clearly essential to the core message.

Although you may be using digital technology to create your visuals and display them when you deliver your presentation, the act of speaking and connecting to an audience—to persuade, sell, or inform—is very much analog. For this reason, it seems only natural to go analog while preparing and clarifying your presentation’s content, purpose, and goals.

Today, all my presentations—and the presentations of my students and corporate clients—will first appear in some form or another as a structured grouping of Post-it notes in a journal, or on a whiteboard...or even on a window.

In order to be open to creativity, one must have the capacity for constructive use of solitude. One must overcome the fear of being alone.

—Rollo May

Asking the Right Questions

It is said that Buddha described the human condition as much like that of a man who has been shot with an arrow. The situation is both painful and urgent. But imagine that instead of asking for immediate medical assistance for his predicament, the man asks for details about the bow that shot the arrow. He asks about the manufacturer of the arrow. He wonders about the background of the people who made the bow and arrow, how they arrived at the color choice, what kind of string they used, and so on. The man asks many inconsequential questions, overlooking the immediate problem.

Our lives are a bit like this. We often do not see the reality right in front of us because we chase ephemeral things—larger salaries, the perfect job, a bigger house, more status—and we worry about losing what we have. The Buddhist would say life is filled with dukkha (suffering, pain, loss, a feeling of dissatisfaction), and we need only to open our eyes to see this. In a similar way, the current state of business and academic presentation brings about a fair amount of a kind of suffering in the form of ineffectiveness, wasted time, and general dissatisfaction, both for the presenter and the audience.

There is much discussion today among professionals on the issue of how to make presentations and presenters better. For them, the situation is both painful and urgent in a sense. It’s important. Yet much of the discussion focuses on software and techniques. What application should I get? Should I get a Mac or a PC? Can I use a smartphone? What animations and transitions are best? What is the best remote control? This is not completely inconsequential, but it often dominates discussions on presentation effectiveness. The focus on technique and software often distracts us from what we should be examining. Many of us spend too much time fidgeting with and worrying about bullets and images on slides during the preparation stage instead of thinking about how to craft the story that is the most effective, memorable, and appropriate for our audience.

The Wrong Questions

In obsessing on technique and tricks and effects, we are a bit like the man who has an arrow stuck in him: Our situation is urgent and painful, yet we are asking the wrong questions and focusing on that which is relatively inconsequential.

Two of the more inconsequential questions I get—and I get these a lot—are “How many bullets should I use per slide?” and “How many slides per presentation?” My answer? “It depends on a great many things…how about zero?” This gets people’s attention, but it’s not the most popular answer. I’ll deal with the bullet points question in the chapter on slide design (Chapter 6). As for how many slides are best, that really is the wrong question. There are too many variables involved to make a concrete rule. I have seen long, dull presentations from presenters who used only five slides and content-rich, engaging presentations from presenters who used more than 200 slides (and vice versa). The number of slides is not the point. If your presentation is successful, the audience will have no idea how many slides you used, nor will they care.

Questions We Should Be Asking

OK, so you’re alone. You’ve got a pad and a pen. You’re relaxed, and your mind is still. Now imagine that presentation you get to give (notice I did not say “have to give”) next month…or next week or (gulp!) tomorrow. Jot down the answers to these questions:

How much time do I have?

What’s the venue like?

What time of the day will I be speaking?

Who is the audience?

What is their background?

What do they expect of me?

Why was I asked to speak?

What do I want them to do?

Which visual medium is most appropriate for this particular situation and audience?

What is the fundamental purpose of my talk?

What’s the big picture here?

And this is the most fundamental question of all, stripped down to its essence:

What is my core point?

Or put it this way: If the audience remembers only one thing from your presentation (and you’ll be lucky if they do), what do you want that to be?

Two Questions: What’s Your Point? & Why Does It Matter?

A lot of the presentations I attend feature a person from a specialized field giving a talk—usually with the help of multimedia—to an audience of business people who are not specialists in the presenter’s technical field.

This is a common presentation situation. For example, an expert in the area of biofuel technology may be invited to give a presentation to a local chamber of commerce about the topic and about what his company does. Recently, I attended such an event, and after the hour-long talk was over, I realized the presentation was a miracle of sorts: Until that day, I didn’t think it was possible to listen to someone make a presentation with slides in my native language of English and still not understand a single point that was made. Not one. Nada. I wanted my hour back.

The wasted hour was not the fault of the software or bad slides, however. The presentation would have been greatly improved if the presenter had simply kept two questions in mind while preparing for the talk:

What is my point?

Why does it matter?

It’s hard enough for presenters to find their core message and express it in a way that is unambiguously understood. But why does it matter? This is where people really stumble. Often, the presenter is so close to his material that the question of why it should matter simply seems too obvious to make explicit. Yet, that is what audiences are hoping you’ll tell them. “Why should we care?” That’s going to take persuasion, emotion, and empathy in addition to logical argument. Empathy comes into play in the sense that the presenter must understand not everyone will see what to him is obvious, and others may understand well but not see why it should matter to them. When preparing material for a talk, good presenters try to put themselves in the shoes of their audience members.

To get back to my wasted hour, the presenter, who was smart, accomplished, and professional, failed before he even started. The slides looked as if they were the same ones used in previous presentations to more technical audiences, an indication that he had not thought first and foremost about his audience that day. He failed to answer the important question: “Why does it matter?” In the preparation stage, he also failed to remember that presentation opportunities such as this one are about leaving something important behind for the audience.

Dakara Nani? (So What?)

In Japanese, I often say to myself, “Dakara nani?” which translates roughly as “So what?” or “What’s your point?” I say this often while I am preparing or helping others prepare their material.

When building the content of your presentation, you should always put yourself in the mind of the audience and ask, “So what?” Ask yourself the really tough questions throughout the planning process. For example, is your point relevant? It may be cool, but is it important to further your story or to support your lesson. Or, is it included only because it seems impressive to you? Surely you have been in an audience and wondered how the presenter’s information was relevant or supported her core point. If you can’t answer that question, then cut that bit of content out of your talk.

Can You Pass the Elevator Test?

If Dakara nani does not work for you, then check the clarity of your presentation’s core message with the elevator test. This exercise forces you to sell your message in 30–45 seconds. Imagine this situation: You are scheduled to pitch a new idea to the head of product marketing at your company, one of the leading technology manufacturers in the world. Both schedules and budgets are tight; this is an extremely important opportunity if you succeed in getting the OK from the executive team. When you arrive at the admin desk outside the vice president’s office, he comes out with his suitcase and briefcase in hand and says, “Sorry, something’s come up. Give me your idea as we walk down to my car.” Could you sell your idea in the elevator ride and the walk to the parking lot? Sure, the scenario is unlikely, but it’s possible. What is more likely, however, is for you to be asked to shorten your talk down from, say, 20 minutes to 5 minutes or from a scheduled hour to 30 minutes on short notice. Could you do it? You may never have to, but practicing what you would do in such a case forces you to get your message down and make your overall content tighter and clearer.

(Image in slide from Pearson Asset Library.)

(Image in slide from Pearson Asset Library.)

Handouts Can Set You Free

If you create a proper handout for your presentation during the preparation phase, then you will not feel compelled to say everything about your topic in your talk. Preparing a proper document—with as much detail as you think necessary—frees you to focus on what is most important for your particular audience on that particular day. If you create a proper handout, you will also not worry about the exclusion of charts, figures, or related points. Many presenters include everything under the sun in their slides “just in case” or to show they are “serious people.” It is common to create slides with lots of text, detailed charts, and so on, because the slides will also serve as a leave-behind document. This is a big mistake (see the upcoming sidebar, “Create a Document, Not a Slideument”). Instead, prepare a detailed handout, and keep the slides simple. Each case is different, of course, but generally speaking, try to avoid the practice of distributing a printed version of your slides as a handout. Why? David Rose, expert presenter and one of New York City’s most successful technology entrepreneurs, puts it this way:

“Never, ever hand out copies of your slides, and certainly not before your presentation. That is the kiss of death. By definition, since slides are speaker support material, they are there in support of the speaker…YOU. As such, they should be completely incapable of standing by themselves, and are thus useless to give to your audience, where they will be guaranteed to be a distraction. The flip side of this is that if the slides can stand by themselves, why the heck are you up there in front of them?”

—David S. Rose

Slides, Notes, Handouts

If you remember that there are three components to your presentation—the visuals (slides), your notes, and the handout—then you will not feel the need to place so much information in your slides or other multimedia. Instead, you can place that information in your notes (for the purpose of rehearsing or as a backup) or in the handout. This point has been made by presentation experts such as Cliff Atkinson, yet most people still fill their slides with volumes of text and hard-to-see data and simply print out their slides instead of creating a separate leave-behind document. (I have used the four slides on this page below while making this point during my live talks on presentation design.)

Create a Document, Not a Slideument

Slides are slides. Documents are documents. They aren’t the same thing. Attempts to merge them result in what I call the “slideument.” The creation of the slideument stems from a desire to save time. People think they are being efficient—a kind of kill-two-birds-with-one-stone approach or iiseki ni cho in Japanese. Unfortunately (unless you’re a bird), the only thing “killed” is effective communication. Intentions are good, but results are bad. This attempt to save time reminds me of a more fitting Japanese proverb: Nito o oumono wa itto mo ezu or “Chase two hares and get none.”

Projected slides should be as visual as possible and support your points quickly, efficiently, and powerfully. The verbal content, the verbal proof, evidence, and appeal/emotion come mostly from your spoken word. But your handouts are completely different. With those, you aren’t there to supply the verbal content and answer questions, so you must write in a way that provides at least as much depth and scope as your live presentation. Often, however, even more depth and background information are appropriate because people can read much faster than you can speak. Sometimes, a presentation is on material found in a speaker’s book or a long journal article. In that case, the handout can be quite concise; the book or research paper is where people can go to learn more.

Do Conferences Encourage Slideumentation?

As proof that we live in a world dominated by bad presentations, many conferences today require speakers to follow uniform slide guidelines and submit their files far in advance. The conference then prints these “standardized slide decks” and places them in a large conference binder or includes them on the conference DVD for attendees to take home. Conference organizers are implying that a cryptic series of slides with bullet points and titles makes for both good visual support in your live presentation and credible documentation of your presentation content long after your talk has ended. This forces the speaker into a catch-22 situation. The presenter must say to herself, “Do I design visuals that clearly support my live talk, or do I create slides that more resemble a document to be read later?” Most presenters compromise and shoot for the middle, resulting in poor supporting visuals for the live talk and a series of bad document-like slides filled with text and other data that do not read well (and, therefore, are not read). A series of small boxes with text and images on sheets of paper do not a document make.

The slideument isn’t effective, it isn’t efficient, and it isn’t pretty. Attempting to have slides serve both as projected visuals and as stand-alone handouts makes for bad visuals and bad documentation. Yet this is a typical approach. PowerPoint and other digital presentation tools are effective for displaying visual information that helps tell your story, make your case, prove your point, and engage your audience. Presentation software tools are not good, however, for making written documents.

So why don’t conference organizers request that speakers send a written document (with a specified maximum page length) that covers the main points of their presentation with appropriate detail and depth? A Microsoft Word or PDF document written in a concise and readable fashion with a bibliography and links to even more details for those who are interested would be far more effective. When I get home from a conference, do organizers really think I’m going to attempt to read pages of printed slides? One does not read a printout of a two-month-old slide deck. Rather, one guesses, decodes, and attempts to glean meaning from the series of low-resolution titles, bullets, charts, and clip art—at least they do that for a while…until they give up. With a written document, however, there is no reason for shallowness or ambiguity (assuming one writes well).

To be different and effective, use a well-written, detailed document for your handout and well-designed, simple, intelligent graphics for your visuals. And while it may require more effort on your part, the quality of your visuals and takeaway documents will be dramatically improved. It’s not about making things easier for us, it’s about making things easier for them, the audience.

Avoiding the Slideument

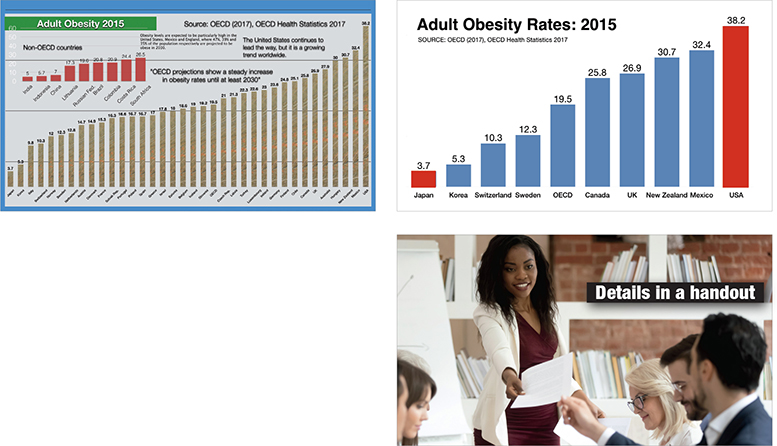

The slide below on the left displays obesity rates for 45 countries in two bar charts. The bar graphs were made in Microsoft Excel and pasted into slideware. It’s common for people to take detailed data such as this from Excel or Word documents and paste them into display slides for a presentation. But it’s rarely necessary to include all this data in an on-screen visual for a short live talk. If it is necessary to examine so much data during the presentation, it would be better to put the charts in a handout. The low resolution and limited real estate of display screens makes it difficult to read labels at such small sizes anyway. It’s usually better to use only the data that truthfully and accurately support your point. In this example, the point is to show how the U.S. obesity rate is much higher than the rate in Japan. It is not necessary to show the rates for so many other countries; this information is better included in a handout. Moreover, if you simplify the charts that you display in the actual presentation, you’ll never have to utter the dreaded line, “Sorry, I know you can’t really see this but...”

Instead of using a detailed chart that will appear cluttered and difficult to read, try creating a simpler visual for the slide and place the detailed charts and tables in a leave-behind handout where you have more space to present the details in a proper layout.

The Benefit of Planning Well

If you prepare well, and get your story down pat—well enough to pass the elevator test—then you can sell your core message well in any situation. A friend of mine, Jim in Singapore, sent me an e-mail sharing a good example of what can happen when you do this work in the preparation stage.

Dear Garr…got this new prospect and have been trying to get in front of the guy for months. Finally get the word he’ll see me next week. I know he is a super short attention span guy, so I used a simple approach and agonized over the content and the key message and then the graphics. We get to the office and begin with the usual small talk that starts a meeting, and suddenly I realize we’ve gone over the points of the presentation in our conversation and he has agreed to move forward. Then he looks at his watch and says great to see you thanks for coming in. As we walk out of the building the two guys that work for me say, “Hey, you never even pulled out the presentation and he still bought the deal—that was great!”

Meanwhile I’m in a complete funk: “What about all my preparation time? He never even saw my presentation. What a waste of time putting the whole thing together!” Then the light went on. Presentation preparation is about organizing thoughts and focusing the storytelling so it’s all clear to your audience. I was able to articulate the points because I had worked those through in the preparation of the presentation. Even the graphics had made me think the presentation through and became a part of the presentation even though the audience never saw them.

Jim makes an excellent point here. If you prepare well, the process itself should help you thoroughly know your story. With proper preparation, you should be able to still tell your story even if the projector breaks or if the client says, “To heck with the slides, just give it to me straight.”

The planning stage should be the time when your mind is most clear with all barriers removed. I love technology, and I think slideware can be very effective in many situations. But for planning, go analog: Use a paper and pen, whiteboards, a notepad in your pocket as you walk down the beach with your dog…whatever works for you. Peter Drucker said it best: “The computer is a moron.” You and your ideas (and your audience) are all that matter. So try getting away from the computer in the early stages when your creativity is needed most. For me, clarity of thinking and the generation of ideas come when my computer and I are far apart.

The purpose behind getting off the grid, slowing down, and using paper or whiteboards during the preparation stage is to better identify, clarify, and crystallize your core message. Again, if your audience remembers only one thing, what should that be? And why? By getting your ideas down and your key message absolutely clear in your mind and on paper first, you’ll be able to organize and design slides and other multimedia that support and magnify your content.

In Sum

Slow down your busy mind to see your problem and goals more clearly.

Find time alone to see the big picture. Take a “forest bath.”

For greater focus, try turning off the computer and going analog.

Use paper and pens or a whiteboard to record and sketch out your ideas.

Key questions: What’s your main (core) point? Why does it matter?

If your audience remembers only one thing, what should it be?

Preparing a detailed handout keeps you from feeling compelled to cram everything into your visuals.