Chapter 16

The Engagement Session

Abstract

PrD consists of two parts, a Creation Session and the Engagement Sessions. An Engagement Session is a conversation. It appears similar to a usability study: The team asks stakeholders to engage with an artifact and perform tasks with it. It appears similar to a design presentation: The team asks stakeholders to reflect on an artifact. But it is neither of those. In an Engagement Session, the team asks external stakeholders to react to its assumptions by using an artifact. Engagement Sessions require expert facilitation (discussed in Chapter 14), the right stakeholders, and knowing when to stop.

Keywords

Engagement Session

artifacts

sampling

maximum variation

hot wash

script

travel

The proper function of a critic is to save the tale from the artist who created it.

—D.H. Lawrence

Overview

The team has completed a Creation Session and has an artifact, ready to engage with external stakeholders. Team members are cautiously hopeful their assumptions will resonate. The relative informality of the Creation Session contrasts sharply with the discipline of the Engagement Session. The external stakeholders—whether customers, clients, employees, or otherwise—have their own time pressures, commitments, and priorities. We schedule Engagement Sessions around their needs.

This chapter covers the following details about running Engagement Sessions:

• Prepping for Engagement Sessions, including sampling, calendaring, and logistics

• Trade-offs between remote and collocated sessions

• Number of stakeholders

• Facilitating the session

• What to do after the session

Simply put, the Engagement Session is a conversation: an intimate, geeky conversation about the meaning of an object. But that description belies the intricacies of the Engagement Session. The simplicity of the Creation Session is opposite to the Engagement Session: The Creation Session is complicated to set up; getting people in the room is relatively easy. Facilitation is at the group level: encouraging, energetic, and task oriented. Contrast this with the Engagement Sessions: Setup is simple; getting the stakeholder in the room is the challenge. Facilitation is intimate, intense, and improvisational.

As we discussed in Chapter 14, this is improvisation at its finest. The Facilitator monitors in real time whether a reaction is leading to new insights or is a distraction. Because the Engagement Session is about a conversation, it looks a lot like other forms of interviews: usability tests, field research, and requirements gathering. The key difference is the artifact. The artifact both initiates and anchors the conversation. As a social object it forges the relationship between the stakeholder and the team’s assumptions.

Throughout the book, we’ve emphasized the need to be in the same room, whether during the Creation Session or during the Engagement Session. As with the Creation Session, it is possible to successfully run remote Engagement Sessions. The trade-offs of running remote Engagement Sessions are significant. With reduced cost comes reduced information. We discuss these trade-offs in this chapter.

Prepping for the Engagement Session

Sampling

PrD is a “small numbers” research effort. There’s nothing remotely interesting about the results in a statistical sense. With only a handful of interviews, perhaps dozens of key insights each, the outcome is a set of stories or themes. The search isn’t for averages, confidence intervals, or the like. The focus is on themes, ideas, turns of phrases, analogies, and metaphors. We analyze the results by steeping ourselves in the reactions from stakeholders: a torrent of words, feelings, and beliefs.

We can’t talk to every potential stakeholder. We’re only going to talk to a few people, altogether. How do we decide whom to talk to? How do we know the stories we’re hearing apply across the entire population? We delve into the principles of sampling to improve our outcomes (Figure 16.1).

Figure 16.1 Sampling: finding only the chocolate coconut–flavored jelly beans

Users

The Engagement Sessions are with people who would use the product or service the internal team intends to build. External stakeholders are actual, intended users, because we’re aiming to learn about the users, not the artifact. The artifact is merely an embodiment of the team’s assumptions. But it is designed to be used, because through its use, the stakeholder reveals her reactions to those assumptions. As The Case of the PowerPoint Play illustrates, the product was a PowerPoint deck, a deck the VP was expected to use. In using it, he revealed his level of discomfort with its content.

Sample Size

Our sample starts with actual, intended users of the product/solution. But how many? It’s natural to want some convenient rule, such as usability’s famous “five-user assumption”1 (a rule that has only limited validity). As of this writing there is no such rule of thumb for PrD. It’s also natural to desire some rigorous quantitative assessment. In inferential statistics there are ways to quantitatively assess the likely sample size needed for certain comparisons. Such measures don’t exist in PrD. “Gut feel” is typically the criterion used.

Such an approach is common. Qualitative researchers explore a problem and understand its context. They dive into meaning and uncover variables of interest.2 The aim is deep understanding, not estimating confidence intervals or calculating statistical significance. Still, sampling is about representativeness and inference: studying a small portion of the population to infer about the larger group. PrD, like any study relying on sampling, makes inferences. Why bother learning about someone’s needs, goals, and frustrations if they have nothing to do with the goals and needs of the larger group? In PrD, the key attribute defining the sample is use: PrD requires us to engage with actual, intended end-users.

Saturation

The problem with representativeness in qualitative methods (e.g., interviewing) is the data from a session speaks to only that particular interaction.3 In qualitative research, representativeness is expressed as data “saturation.” Saturation tells us we keep increasing our sample size, keep interviewing, until we’re not capturing enough new insights to warrant going further. So it is with PrD.

There is no hard and fast rule for when we achieve saturation. It’s a matter of diminishing returns. Diminishing returns applies to insights about a stakeholder’s mental model, goals, and frustrations. It applies to how much an artifact continues to reveal her real work and her real needs. The more Engagement Sessions we run, the less novelty emerges about the problem space. How many sessions are needed to achieve saturation? As few as three are sufficient.

How is that possible? If talking to a few folks sheds light on some ideas, how do we know talking to a few other stakeholders won’t paint a completely different picture? By sampling. We test hypotheses and minimize the risk of unrepresentative sessions via purposive sampling. We select specific external stakeholders based on purposely selected characteristics. The art is in choosing the right characteristics: ones we think are important to our assumptions.

For example, we believe a new offering will resonate more with loyal buyers (people who have been buying from us for over 10 years) than for recent customers (those who just came on board in the past two months). We can create a purposive (or “theoretical”) sample based on longevity of tenure as a customer. We can pick a handful of folks from each length of tenure and have them engage with the artifact in exactly the same way. To prevent confounds, we would carefully conduct ourselves the same with each group, regardless of tenure.

Based on our assumptions, we’d expect to have very different Engagement Sessions. If that was the case, we’d be more confident there was a difference. If there wasn’t any appreciable difference in their engagements, we’d have to rethink our assumptions. By “appreciable difference,” we mean a clear distinction in the way stakeholders approached and worked with the artifact, the questions they raised, and confusions it may have created for them.

The key assumption here—length of customer tenure would affect stakeholder engagement—should be immediately obvious. If the two populations behave similarly, we should feel confident our assumptions were wrong, at least for the two groups in our Engagement Sessions. (By “similarly” we mean so close to the same that a third party reading the transcripts wouldn’t be able to tell the difference.) If the PrD was quick and dirty, the expedient thing to do would be to abandon the assumption and try something else. If this assumption was key to a major project, we’d likely run a quantitative study to be more certain.

We reduce arbitrariness and maximize representativeness by purposely seeking stakeholder qualities in which we’re most interested. We don’t create a sample by picking people arbitrarily (or even pseudorandomly) but instead by an up-front conscious definition of how we’re going to populate the sample. There are several types of purposive samples used in qualitative research:4

• Extreme or Deviant Case: Learning from highly unusual manifestations of the phenomenon of interest, such as outstanding success/notable failures, top of the class/dropouts, exotic events, and crises.

• Intensity: Information-rich cases that manifest the phenomenon intensely, but not extremely, such as good students/poor students and above average/below average.

• Maximum Variation: Purposefully picking a wide range of variation on dimensions of interest. It documents unique or diverse variations that have emerged in adapting to different conditions. Identifies important common patterns that cut across variations.

• Homogeneous: Focuses, reduces variation, simplifies analysis, and facilitates group interviewing.

• Typical Case: Illustrates or highlights what is typical, normal, and average.

• Stratified Purposeful: Illustrates characteristics of particular subgroups of interest; facilitates comparisons.

• Critical Case: Permits logical generalization and maximum application of information to other cases, because if it’s true of this one case, it’s likely to be true of all other cases.

• Snowball or Chain: Identifies cases of interest from people who know people who know people who know what cases are information-rich, that is, good examples for study and good interview subjects.

• Criterion: Picking all cases that meet some criterion, such as all children abused in a treatment facility. Quality assurance.

• Theory-Based or Operational Construct: Finding manifestations of a theoretical construct of interest so as to elaborate and examine the construct.

• Confirming or Disconfirming: Elaborating and deepening initial analysis, seeking exceptions, and testing variation.

• Opportunistic: Following new leads during fieldwork, and taking advantage of the unexpected.

• Random Purposeful (still small sample size): Adds credibility to sample when potential purposeful sample is larger than one can handle. Reduces judgment within a purposeful category. (Not for generalizations or representativeness.)

• Politically Important Cases: Attracts attention to the study (or avoids attracting undesired attention by purposefully eliminating from the sample politically sensitive cases).

• Convenience: Saves time, money, and effort. Poorest rational and lowest credibility. Yields information-poor cases.

• Combination or Mixed Purposeful: Triangulation, flexibility, and meets multiple interests and needs.

Any one of these can be considered a way to select which stakeholders to work with. Typically, however, we work with a maximum variation purposive sample. That is, we try to include individuals with widely varying differences in the attributes of interest. In such a sample, if they all respond identically to the Engagement Sessions, we have increased our confidence those variables don’t really matter by identifying “important common patterns that cut across variations.”

Some of the other extreme purposive samples make sense in particular situations, such as finding only experts in the domain or, obversely, only newbies. It just depends on our assumptions. We avoid a purposive sample of “convenience.” Convenience in this case is only in creating the sample, but the sample wastes time. With such a purposive sample, at the end of the Engagement Sessions we really don’t know whether we’ve learned anything about our population. We just know how the people we could get ahold of easiest reacted to our assumptions.

For us to create a maximum variation purposive sample, we decide what the dimensions are—geography, industry, and type of Web browser—whatever they might be. We decide what specific variables we need within the dimensions (the United States, Japan, France for geography, for example). Then we go about getting at least three individuals for each variable. For example, if we are interested in six different dimensions with three variables each, we’d need to engage with 3 × 3 × 6 = 54 people. In fact, we can reduce the total number of people based on how many characteristics an individual may have. In the most absurdly reductionist case, we might find nine people all of whom share the same variables across the six dimensions. Possible, but highly unlikely.

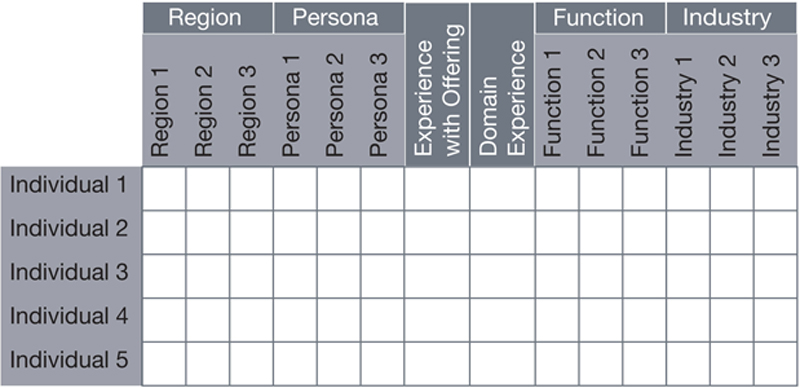

We create a small table of the characteristics and through a quick evaluation of the stakeholders (a simple email, phone call, or perhaps database/log files can tell us the answers we need), we fill in the cells. An example is given in Figure 16.2.

Figure 16.2 Characteristics table

In practice this takes a few hours at most, assuming we have a good handle on our stakeholders. If we don’t, then PrD itself isn’t slowing us down. In fact, any user-centered technique would run into the same hurdle: figuring out who our stakeholders are and how to reach out to them.

Recruitment

Though time consuming, recruiting for PrD is pretty simple, once we’ve figured out who our candidate pool is. The easiest method is to pull from a customer list, usually owned by the sales and marketing group, public relations group, or the product line. Sometimes the list has many of the dimensions the team is already interested in. For those that are missing, we can craft a quick “screener.”5

In the sections that follow we describe situations typical in “B2B” engagements. In some ways the process is easier working from one business to another than working with consumers. Businesses have clear policies for employee engagement; facilities are available, and the stakeholders understand conceptually what the team is trying to do.

Still, everything we discuss in the following sections applies equally well in the consumer context, even if the particulars shift. For example, where a consumer may not require security clearance from the team, she may expect to meet us in a public location for her own peace of mind. Similarly, just as working in factories requires specific preparation, so too does working with minors or at-risk populations.

Using Sales Teams

In general, we rely on our sales people to refer us to potential candidates. When working with sales, we are careful to specify who we are looking to interview, since they may have other reasons for us to talk to customers. When our reasons align, great! But we don’t accept names willy-nilly; we work with them using the purposive sample. The internal team may have names of prospects from prior engagements or relationships they’ve established. Regardless, the team should get approval from the sales teams before talking to customers. Even if we have an established relationship with customers, we let the sales team know we’re intending to reach out to them.

While emailing is easy, it isn’t as effective as a direct phone call. In a few minutes, assuming they’ll take the call at all, we can quickly establish:

• The purpose of the call (no, we’re not selling anything—we’re really and truly trying to make life better).

• Whether this is the right person (based on the purposive sample) and if not, who might be.

• If it is the right person, getting her agreement to work with us. This requires additional effort, best done by phone. (NDAs need to be in place if they aren’t already; we may need to overcome objections about implicit endorsements of products and so forth.)

User Groups

An organization’s sponsored user groups (assuming it has some) or social communities can be another great way to find prospective stakeholders of products and services. Broadcasting a general offer to the group will at least get the word out quickly and efficiently. PrD’s unusual requirements will require more detailed conversations once a prospect responds. Be advised, user groups, or interest groups on social network sites, are populated by all sorts of denizens— some are professional “respondents.” Others may be competition. Broadcasting an invitation to participate has some risk. Wording should be considered carefully.

Panels of Experts

Some companies invite customers to opt-in to ongoing market research efforts. In some cases, these become go-to panels against which marketing bounces key ideas. As long as these individuals fit the purposive sample they should be fine, with one exception. Any customer who has been participating frequently may no longer be representative of the broader population. One of the characteristics we use in our samples is how recently the individual was contacted.

Support Call Center

Another source of recruitment is the support call center. While customers may have explicitly opted out of any marketing contacts, product research participation is often not as carefully articulated. Work with the support center and see if they can offer an opportunity to callers who meet certain criteria (the purposive sample chart) and confirm they’d be okay with a follow-up call from someone on the UX team.

Web or Social Media

Sometimes a pop-up survey on a website or a tweet to a community of interest finds suitable candidates. The annoyance and spam factors need to be balanced against the benefit of breadth.

Third Parties

Recruiting can be tedious, time consuming, and a challenge. But in our experience, outsourcing recruiting to a third party has not been effective. We’ve tried third-party market research recruiters and internal admins, but neither have worked well. From the perspective of market research, PrD is strange. Recruiting companies have amazing technologies to rapidly screen candidates, but they may not have the right characteristics in their call lists. Getting the script right and training the call center staff takes time. Perhaps more time than if we just found a few handfuls of people ourselves.

Internal staff, such as an admin or a project manager, will need to be trained on the process to assist with recruiting. If not properly trained, when the prospective stakeholder says they’re not interested, the assistant may accept the answer without probing further. Perhaps the prospects don’t understand the process; perhaps they think we’re selling them something. Unless the recruiter understands the PrD process, it is difficult for them to overcome objections.

If we are eventually able to work with reluctant stakeholders, they become our greatest “inside salespeople.” After going through a session, they see how valuable and fun the experience is. Whenever possible, we use these recent “believers” to help find others they know in the organization. We balance such “snowball” sampling against our purposive sampling chart.

Calendaring, Communication, Setting Expectations

We don’t expect to schedule our first stakeholders sooner than two weeks after our first contact with them. Naturally this depends on stakeholder availability, so we really can’t predict. If time is of the essence, we don’t wait. Once we know the date for the Creation Session, we schedule Engagement Sessions to follow immediately afterward.

We start with a brief phone call confirming they’re interested and identifying a specific time and date. After we hang up, we send a brief email describing what we’re planning on doing. The email is redundant: It covers everything we discussed in the phone call. People are busy; the process is new to them; some details are important for them to know. It both is courteous and reduces misunderstandings to provide a brief overview of what they can expect during the session.

A day or so before the meeting we confirm they’ve completed any outstanding tasks required of them (such as scheduling a conference room, or having access to a particular area in their workplace). This final reminder primes them for the session, especially helpful if it had been scheduled weeks before. If there is more than one individual participating, whether together or separately, we schedule a collective orientation session. We don’t ask stakeholders to do prework or prepare for the Engagement Session, but this reminder helps if they need to prepare the environment for the sessions.

If the artifact is to be used under “normal” working conditions, we’ll want to make sure the stakeholder has planned for the team’s access to the usual and customary environment in which he works. The stakeholder may need to get special security clearances or may need to notify peers the group is arriving. Of greatest concern is the normal work of interest that is actually going to occur while the team is there. In such situations, PrD begins to share some common characteristics with contextual design.6 Usage is highly affected by context: whether the stakeholder works on the factory floor or in a cubicle, etc. When the stakeholder is distracted by normal interruptions, external validity of the team’s observations is increased.

During our conversations, we stress our interest in seeing the stakeholder doing actual work. Even so, we often arrive and are ushered into a conference room where the stakeholder is happy to engage with us. If the Engagement Session’s success depends on the stakeholder using the artifact under usual circumstances, we may start the session in the conference room. Soon after the orientation is over, we ask to move to the location where the stakeholder would normally perform the desired activity.

Special Preparation

The team may need to prepare for the Engagement Session beyond the artifact and script. The stakeholder may require the team to get security clearances, prepare specific identification documents, don special clothing, or comply with other prerequisites so the team can participate. We have had some embarrassing moments when team members failed to have the proper IDs and had to stay in the lobby while the rest of us proceeded with the session.

Nondisclosure Agreements

One mutual prerequisite most companies require is an NDA. For some organizations this is practically an automated process; for others it is a “one-off” every time. Because the team will be discussing the stakeholder’s work (or play), and the stakeholder will have an opportunity to explore the team’s thinking, everyone must agree to the confidentiality of the conversations. For some stakeholders this requirement cannot be overcome and they may need to defer their participation. For others, they may require additional people in the session with whom they can consult if the conversation enters prohibited territory.

Regardless of the level of restriction, it is up to the Facilitator to continue to reinforce a key point: The team isn’t interested in secret information. In almost all cases, stakeholders can discuss their work, demonstrate how they would use the artifact, or provide use cases without revealing company secrets, trade secrets, specific personal information, or other harmful information. Although PrD expects a certain level of specificity, PrD’s success doesn’t require secret information.

Logistics: Traveling with an Artifact, Traveling with a Herd

The Engagement Sessions require very little infrastructure: a place to meet, preferably where the stakeholder does the activity of interest, and an undisturbed period of time, usually less than an hour.

Traveling with more than a couple of people does create some logistical issues: transportation, lodging, food, and any special needs. In larger organizations, an admin or PM can often take care of these details, but if you are on your own, you’ll need to account for the additional effort of coordinating all of the little details. Sure, each individual can make their own travel plans but that is suboptimal: Much discussion and work is done in airport gates, in the car between meetings, and the like. The group in short, should expect to travel as a group. For some, food is essential. For others, a quick pickup at a convenience store or gas station and a cup of coffee is all they need (Figure 16.3).

Figure 16.3 A PrD fuel stop when the team is on the go

To keep costs down, we schedule multiple stakeholders in the same region. We take the time to know team members’ food preferences and align on meals in advance of the trip. Again, much work is done over meals: conversations, insights, and reviews of the sessions; it’s essential to capture everyone’s viewpoint.

Usually we craft artifacts to fit in the overhead bin of an airplane, but not always. In The Case of the New Case, the boxes were large enough to require special shipping. As the team is crafting the artifact, they’ll need to keep travel in mind; if travel is by air, either the budget needs to address shipping through or the artifact needs to be sized small enough to avoid shipping costs.

Crafting the artifact for travel will be a welcomed challenge for industrial designers or mechanical engineers on the team. We’ve seen artifacts designed to be “knocked down” for easy reassembly after arrival. But, as we discussed in Chapters 5 and 8, we must strike a balance among sophistication, complexity, value, speed, and overall investment. We bias our effort and investment toward the simplest possible artifact to drive the right conversations with stakeholders.

Remote or Collocated

With so much work being done digitally and so many relationships and interactions intermediated by screens, it seems quaint and outdated to actually meet face to face. Quaint, perhaps, but the information gleaned working side by side is substantially more valuable than through a 2D screen. At least three reasons compel us to meet with our stakeholders face to face: nonverbal information, context and simplicity.

Nonverbal

Hearing the nuance of confusion, annoyance, or joy in a stakeholder’s voice is one of the key pieces of information we listen for as he attempts to work with the artifact. Tone of voice, however, can be more difficult to interpret without nonverbal cues to help. A sigh that sounds like frustration on the phone might be a reaction to something we can’t see (Figure 16.4).

Figure 16.4 Working directly with stakeholders improves information capture

Body language, facial expressions, gestures, and other means of communicating are mostly lost through a phone line, whether supplemented with a video camera or not. With multiple Observers in the room, additional points of view help confirm what a single Observer thought she saw.

Context

Expecting stakeholders to work under “normal” circumstances is unlikely if they are working with us by hosting a videoconference call, unless of course that is the context in which the team is interested. Working on the factory floor, walking through the halls from one room to another, or getting interrupted by coworkers as they try to use the artifact, these “distractions” from pristine laboratory conditions are often the data of interest. If the artifact must address the stakeholders’ true context, how can we know we’re getting the right information outside of that context?

PrD provides such a rich stream of information that we’re baffled teams choose to throttle that stream by running the Engagement Sessions remotely. As we discussed in detail in Chapter 9, organizations cite several reasons for hosting sessions remotely, but they all boil down to perceived cost.

Simplicity of Engagement

Although traveling increases the complexity of logistics for the team, it makes life simple for the stakeholder. Asking stakeholders to set up remote technologies to share screens, observe their reactions on video and the like are not tasks they do frequently enough to be easy.

Even in high-tech companies in which employees rely on such technologies, we’ve had to abandon sessions because of system failures. Nothing beats sitting across from a stakeholder in terms of simplicity.

To Record

Recording the Engagement Session is a controversial decision. We are in the camp who believes recording is an essential tool; others think it’s not worth the effort. Whether you record or not depends, once again, on your objectives. Figure 16.5 provides some of the key reasons to record or not.

Figure 16.5 Pros and cons of recording

We discuss each of the advantages to record, along with mitigations should the team decide not to record. Further, we discuss each of the downsides of recording, and appropriate mitigations should the team wish to record.

Capturing Words, Gestures, and Behaviors Literally

When we are trying to identify metaphorical thinking on the part of our stakeholders, we must capture their exact words and phrases. Recording captures everything, whether using a smartphone’s recording capability, a special pen (e.g., Livescribe™), or a video camera. The team can relax and listen to the key things attracting its attention. There is no other way to capture a stakeholder’s gestures, posture, or behaviors without recording them on video. Under certain circumstances, these become crucial data points for design decisions as well as communicating out to sponsors.

When working with no other Observers (a practice we don’t recommend, as we discussed in Chapter 10), recording allows the Facilitator to relax without worrying about capturing every sentence.

If the sessions are not recorded, the team must find a way to capture gestures, literal turns of phrase, and the like. In our teams, one of us acts as the “scribe” (in general, one of the Observers), capturing everything she hears. While this approach gets the words straight, the team relies on everyone’s memories (or notes—ideally more than one person should be taking notes) to reconstruct stakeholder gestures and behaviors. When we rely on taking notes, we:

• Include as many exact quotes as possible.

• Try not to paraphrase.

• Use the stakeholder’s terminology.

• Avoid using the team’s own jargon.

In short, when we take notes, we don’t put words in the stakeholder’s mouth. We clearly distinguish direct quotes and comments.

A master Facilitator can also act as the scribe, capturing stakeholder comments almost word for word. Under such circumstances, the Facilitator/scribe will miss important points in the stream of stakeholder responses. It’s perfectly fine to ask the stakeholder to repeat whatever was missed, as long as such interactions occur infrequently. We block off time immediately following the session (while the interaction and discussion are still fresh) to review the notes and add in missed details and comments. Here again, however, merely transcribing words fails to capture stakeholder emotions, gestures and other non-verbal cues.

Providing Evidence to Skeptics

We need to make a case for Engagement Session results. This is especially true when stakeholder responses differ radically from the HiPPO (highest-paid-person’s opinion). Depending on the level of trust in the team’s organization, a simple report out may suffice. In contrast, for some teams only one thing tells it like it is: hearing the results straight from the stakeholders’ mouths.

The best approach is to bring the HiPP (the highest-paid person behind the HiPPO) with the team! She can hear the stakeholders’ reactions, potentially probe (with the Facilitator’s permission, of course!), and reflect with the team between sessions. Such opportunities are rare. When we need to convince a skeptical sponsor, we show them the evidence. Video tells the story without intermediation.

Replaying stakeholder videos doesn’t guarantee we’ll overcome skeptics. Regardless of what we use to convince skeptical sponsors, there must be enough advocates for the team’s point of view. When a handful of people who’ve observed the results can present during the report out, the sheer numbers of impassioned voices is usually enough to counter the HiPP’s skepticism.

Highlight Reels

When introducing PrD to a group, we like to tell stories about the process’s effectiveness, the information captured, and how it differs from methods with which they may already be familiar. A highlight reel summarizing several Engagement Sessions (and perhaps the Creation Session that spawned them) is a powerful storytelling tool.

The downside is highlight reels take a huge amount of time. We estimate every minute of highlight requires an hour of postprocessing time: seeking, editing, compiling, producing, and finishing. For a team member skilled in the art of video work, it’s just a matter of time. If the team lacks such skill, the effort becomes a major challenge, perhaps insurmountable.

Not to Record

Invasive

We are already asking a lot of our stakeholders: Meet with a handful of us, meet us in your home or workplace, and then use this crazy-ass thing we’ve brought along. Now, on top of all of that, would you mind if we just set this camera up over here and let the “unblinking eye” take everything in?

Oh, and could you sign this form please?

Everything about recording adds layers of invasiveness into the initial part of the session. So, yes, the initial portion of the session (as well as some prework around getting approval for recording) is hampered by the recording requirement. For some stakeholders there is no negotiating: No recording devices are permitted anywhere on the premises. In some cases we’ve even had to leave our cell phones at the security desk.

Now, with all that said, assuming we’ve received approval to record, something interesting happens shortly after the Engagement Session begins: Most stakeholders completely forget about the recording device, even if its red light is staring at them across the desk. The session is aptly named: It’s meant to be engaging. Stakeholders become so engrossed in the work they’re doing, in using the artifact, in the conversation, etc., they will remember the recording device only if they speak passionately about something (curse, emphasize a point with a strident tone, tell a “tale”). If it bothers them, the Facilitator reminds everyone the discussion is completely confidential and the device recedes into the background again.

With respect to security policies, except in extremely rare cases (even in cases where the policy is explicit), we’ve received approval for some kinds of recording, such as audio and photographs. We usually go up the chain of command for proper dispensation and/or we agree to specific restrictions.

In brief, if recording is important enough to do, it is possible to get it approved and the device has minimal impact on the stakeholders’ willingness to share openly.

Postprocessing Time

If the team isn’t prepared to add about an hour of listening for every hour of recording, they shouldn’t bother recording audio. If they’re not prepared to add at least 30 minutes of re-viewing for every hour of captured video, we recommend against videoing. These times assume no transcribing, noting, or other metadata capture, just reexperiencing the sessions. If the team is hoping to use the literal words in every session, consider hiring a transcription service or trying audio-to-text automation tools. Even with these alternatives, though, the team will spend considerable time editing and cleaning up garbled sections.

If the team has the budget and resources, this is an excellent summer intern job. We’ve had great success in getting video and audio snippets postprocessed, indexed, and keyworded by using a dedicated resource for several months. The database this created was useful for many years after the fact to help bring new sponsors up to speed quickly or to help ground new design efforts in the work already comprehended.

Running the Engagement Session

The time has arrived to actually engage with a stakeholder. In this section we dig into the many Engagement Session variables, ranging from how many people are in the room to interviewing techniques.

How Many Stakeholders, How Many Team Members?

As we’ve discussed throughout the book, an Engagement Session involves the internal team working with a single external stakeholder. We discussed how many team members should be included in Chapter 10. Here we discuss reasons to adjust those numbers.

How Many Stakeholders?

The majority of Engagement Sessions involve a single stakeholder working with the team, and for good reason: It is much easier. Keeping a single stakeholder focused on the objectives is challenging enough. With additional stakeholders the situational dynamics become very complex, in many instances too complex to handle. We don’t consider dyads (two stakeholders) or triads (three stakeholders) without expert facilitation and a team disciplined in their behaviors and roles. We never have more than three stakeholders in the room. In The Case of the Reticent Respondent, the team had four stakeholders in the room, a major contributing factor to the key participant’s discomfort. We found ourselves in that position because of miscommunications between the team and the group manager. The session only barely succeeded.

A Case for Two

There is one case in which having two (and rarely three) stakeholders in the Engagement Session makes sense: when the assumptions and objectives require individuals work together. The only way to observe stakeholder reaction to an artifact designed for collaborative work is to have multiple stakeholders perform the collaborative work! (It is possible to simulate the coworkers’ actions through a Wizard of Oz approach. Such an approach requires the Wizard to be intimately familiar with the stakeholders’ work. Alternatively, we’ve imagined cases in which the Wizard acts presumptuously to drive important conversations. That approach is a subcase of a single stakeholder working with a team that is simulating the collaborative behavior.)

Consider the case in which there are two stakeholders, each performing different aspects of collaborative activities. The team has oriented them (together to save time), and the Engagement Session has begun. Each is offered an artifact, or the two are offered a single artifact. In any event, during the Creation Session the team will have designed one or more artifacts to enable stakeholder collaboration. One thing the team likely won’t do is have the two artifacts communicating with each other in real time. This implies the team has fielded an operational prototype. As we suggest throughout, such an engagement may be necessary, but it doesn’t leverage PrD to its best advantage.

The artifacts have likely been designed to work together in some clever way, and they may very well communicate with each other. Think of it as a game of Battleship. The two players can’t see each other’s layout, but through a series of moves each affects the other’s, even if those moves are expressed verbally. Using a Wizard of Oz approach, a team member could act as the “system,” drafting up messages and delivering them between the stakeholders. The system could inject messages or state changes into the artifacts independently, as many systems would in the real world, as a means of moving the simulation forward. In one PrD workshop, teams crafted just such artifacts: When the stakeholder used an intelligent drinking glass, the team-member-as-system behaved autonomously, updating the glass’s state with frequent messages.

Note: We are not suggesting having two or three stakeholders simply opining on the same artifact. That is getting close to focus group behaviors, and PrD has nothing to do with focus groups. If more than one stakeholder shows up for the same session when this was not the intent, the internal team apologizes for the error and reschedules. The results from multiple stakeholder participation (when the artifact was not designed for multistakeholder engagement) are so inferior that such sessions are not worth doing.

The Environment: The Room, the Table, the Proxemics

We prefer to have stakeholders engage with us in their natural habitat. Conversations are often triggered by the context in which they perform the activity of interest. If stakeholders spend their time in conference rooms, we’ll set up the Engagement Session in the conference room; if it’s at a restaurant or coffee shop, we’ll do it there.

We want to experience what happens to stakeholders in their preferred context, the interruptions from others, and the stuff they reference in their cube or on the walls. These all help trigger interesting insights. If the activity is a specialized type of work, such as a process in a manufacturing line, observing it in situ is crucial to the team’s understanding. Of course, the team must be flexible; working with the stakeholder in their native habitat isn’t a hard or fast rule. The room may be too small, there may be security concerns, or the mere presence of the team will negatively affect the way the activity is performed. It is far better to engage than not at all, even if it means going to a lunch room or conference room.

Once we’ve determined the context, we turn our attention to arranging the group. The key relationship is among the stakeholder, the Facilitator, and the operator of the system (if there is one; it could be an Observer or the Designer). The first two must be near one another so the Facilitator maintains the right level of intimacy. The system operator must be close enough to the artifact to manipulate it as needed. If the three are standing, they create a U with the stakeholder at the bottom. If they are sitting at a rectangular conference table, the stakeholder should be at the head (which is generally an honored position anyway), with the Facilitator and operator on either side.

All others should be out of the way, but sufficiently close to observe what is going on (Figure 16.6). The team should consider having a floater who unobtrusively walks around as needed. Avoid having a lot of people standing behind the stakeholder for more than a few heartbeats. It’s just creepy. While team members may be interested in how the stakeholder is manipulating the artifact, her facial expressions and body language are equally important.

Figure 16.6 The team steps back from the stakeholder in Engagement Sessions

The Designer may be situated a little way away, with additional supplies in the event a quick design suggestion is called for. For example, the stakeholder may suggest a radical interpretation of the artifact the team hadn’t imagined. (In fact, this very frequently happens.) If it is interesting enough to explore, and it requires the stakeholder to demonstrate, the Designer will need to mock up something quickly (within a minute) for the stakeholder to tear apart.

The Facilitator sits close enough to the stakeholder to observe what is going on and react accordingly. It is an intimate relationship, almost confidential: The stakeholder is revealing things going on in her head. The Facilitator is offering the social object while establishing a sense of security and camaraderie. The Facilitator needs to create the sense of a confidante who can keep the stakeholder’s innermost thoughts safe and secure.

Facilitating the Session

We discussed specifics of PrD facilitation in Chapter 14. Here we offer vignettes of facilitating the Engagement Session.

The team—maybe an Observer, the Facilitator, and a Designer—sit in front of the external stakeholder, and the session begins (Figure 16.7). The Facilitator hands the artifact to the external stakeholder or sets it out on a table in front of her, simultaneously offering the first task. The Facilitator says, “I’d like you to pretend this piece of cardboard with sticky notes on it is a dashboard. For your first task, please check and see how likely it is you’ll make your quota this quarter. As you do, please be sure to voice whatever is going through your mind. Say out loud what you’re seeing, how you’re interpreting the artifact, what your reactions are, as well as anything you find compelling or confusing.”

Figure 16.7 Position the stakeholder at the head of the table

The stakeholder probably isn’t going to dive right in. It’s a slightly odd ask, given how crude the artifact is. It’s unlikely she’ll see how to perform the task right away. The stakeholder has to collect her thoughts; she needs to craft a narrative about performing a task with a somewhat nebulous artifact. It requires her to play pretend, to fill in gaps using tacit knowledge about her work. She must consider possible ways the artifact plays into her work. All of this takes some time, which the Facilitator knows. He remains quiet, knowing surprises will ensue as the stakeholder meanders through the exercise (Figure 16.8).

Figure 16.8 A stakeholder interacting with an artifact

The stakeholder may be hesitant, possibly requiring the Facilitator to ease her into the engagement. Perhaps the stakeholder points to one of the sticky notes and asks, “What is this meant to be?” The Facilitator, recognizing an opportunity to let the stakeholder answer her own question, mirrors it back. “What do you think it might be?” or, “When you look at it, what do you see?” or even, “You tell me.” Maybe the stakeholder remains reticent, buying some time by being literal. She might say, “It’s just a few lines and lots of little circles.” The Facilitator takes this opportunity to redirect by reminding the stakeholder of the task, “Yes, and how might they help you see how likely it is you’ll make your quota this quarter?”

The Facilitator, in short, must be a pest. He should be polite, respectful, and empathetic—and persistent. Offering good prompts and constantly redirecting the stakeholder means overcoming the urge to help. The Facilitator suppresses the human desire to step in to answer the stakeholder’s questions.

Maybe the stakeholder then says, “Well, it could be some type of graph. What is it showing?” Should the Facilitator answer the question? Of course not! Once again, the Facilitator mirrors the question back. But using the same technique repetitively becomes irritating, so the Facilitator has a few different versions of redirection. He responds, “Play pretend. What might it be showing?” or, “You tell me. How might you use this to track progress toward your quota?” By now, the stakeholder has had enough time to think and sees the team is serious. She may laugh at the ridiculousness of the request, a good sign she is starting to play pretend, to engage in creative, abductive thinking.

She says, “Well … the dots here could represent my projects.” Whether this is what your team was envisioning or not, the Facilitator says, “Ok. Tell me more.” The stakeholder, giving it more thought, says, “Maybe the columns represent status, like pending, lost and cancelled, and then some of the columns let me assign which projects I’ll likely claim as wins this quarter.”

Here’s an opportunity to dig a little deeper into the stakeholder’s usual approach to project forecasting. Depending on the team’s objectives, the Facilitator prompts the stakeholder to consider aspects of the artifact related to forecasting. The session’s direction depends entirely on the objectives. In this case, the Facilitator says, “Ok. I see. You’re seeing the columns as project statuses. How does that help you check on progress toward your quota?” The stakeholder responds, “I can see, at a glance, how many pending projects I have in my funnel. I can also see which I’ve assigned confidence ratings to. I can see how many wins I already have. All that helps me do my forecasting. Actually, if a display like this could be built, that would be really, really great. I would definitely like this.”

These last comments by the stakeholder are valuable only in so far as they reveal something about the team’s assumptions. If the team believed such a chart would be useful for doing forecasting, then the stakeholder has validated its assumption. If the team hadn’t heard about confidence ratings before the session, this would be an excellent time to learn more. In any event, the endorsement or judgment about the artifact is completely irrelevant. It’s not about how great the artifact is—it’s sacrificial.

The Facilitator periodically says, “Ok. And what might be missing here?” The stakeholder states the display would need to show the percentage of projects she closes on, historically, to get a better sense of how many pending projects she needs to keep in her funnel. The stakeholder says the associated value of each project is missing. Here the Facilitator invites the stakeholder to add to it or edit it to provide that information. The stakeholder says, “You know, what would be really awesome is if this wasn’t just a display, but something I could use to actually change my projects’ statuses.”

Once again, this could be an important idea the team hadn’t thought of. Or maybe it was exactly what the team had in mind! Without hearing the team present its intended design, the stakeholder offered it up unprompted. When multiple Engagement Sessions result in similar outcomes, the team is assured they are on the right track. This is an example of how the conversation might go, with appropriate prompts and facilitating, and the insights that could follow, all spawned just from the first task.

PrD, like usability, is task-based testing, but as we’ve seen, the aim is not to refine the design. Unlike usability, we’re really not interested in the stakeholder’s ease of completing each task. In PrD, the artifact is vague and ambiguous; it’s the merest wisp of something. As with the notion of cultural probes,8 the point is to learn about the person. When the stakeholders tell us how we’ve failed, we gain insight into their way of thinking. We listen to the ways in which our team’s assumptions are wrong; we listen to the stories the stakeholders tell and the ways in which the idea might be incorporated into their lives. This is the gold.

When is the Engagement Session Finished?

When the last objective has been met, the Engagement Session is over. The objectives are the guardrails within which the session operates. Even if we’ve achieved all of them in the first five minutes, we’re done.

The objectives are only one measure of when the session is over. Sessions sometimes end before accomplishing all of the objectives. The session could be over sooner if the allotted time has run out. While it is perfectly acceptable to ask the stakeholder if she is available for more time, if the time is up, expect to be done. To minimize the chances of this happening, practice the session in advance, perhaps pilot it with a “friendly” and figure out how to pace it so it will complete in time.

When it comes to timing, Engagement Sessions are not any different from other field research engagements—the stakeholder is always in control. There are all sorts of reasons for the stakeholder to end a session before the objectives are met or the time is up. Perhaps she is being called out on an emergency; perhaps she no longer finds value in the session; perhaps she’s just fatigued; perhaps a higher-up has messaged her and she has to drop what she’s doing. Whatever the reason, if the stakeholder has decided the session is over, it’s over.

After the Engagement Session

Postsession Dynamics

Immediately after the session is over, the team collects the artifact and the recording equipment. The last thing we shut down is the recording equipment, if we’re recording at all. Even after we’ve officially closed the Engagement Session we will keep recording as long as people in the room are conversing. The last point is important: The people in the room are conversing. We don’t follow people outside the room with our recording equipment; we’re not the paparazzi. We don’t risk capturing people who have not agreed to be recorded.

Much useful information is shared as soon as the stakeholder feels released from the session. Framed as casual conversation, the discussion after the “official” session is rich with insights. The stakeholder may review a piece of the session; she may offer her interpretation of what she did, or provide additional dimension to her thinking. Here, as in the official session, the team defers participation to the Facilitator. The Facilitator remains the primary point person unless the stakeholder specifically addresses another team member. In any event, we keep at least the audio recording going until we leave the room.

During an Engagement Session the stakeholder will have asked questions that can’t be addressed during the session. We usually reserve a few minutes at the end to answer those questions, providing closure for the stakeholder. As the session winds down, the Facilitator takes a few minutes to allow the team to answer any outstanding questions.

Hot Wash Critique

We don’t schedule sessions back-to-back. We leave 30 minutes minimum between them, assuming no travel time. During this gap, the team conducts a “hot wash critique”9 of what each person heard. Find a quiet place out of the stakeholder’s way where everyone can voice what they observed and what stood out to them. When there isn’t enough time for a hot wash, we have team members annotate or circle their notes to help them remember top-of-mind points (Figure 16.9).

Figure 16.9 The “hot wash” critique occurs immediately after the Engagement Session closes

Capturing impressions during the hot wash is important, especially if there are multiple sessions per day. Sessions start to blur into one another. As each person presents her top impressions, others listen for things they heard or saw. If there is a conflict, the Facilitator makes a note of it but doesn’t stop the process. The team returns to these points after everyone has had their turn. After the first individual reports out, the next reports only things they witnessed that differed from the first. In the interest of time, repeating the same observations provides no value. Finally, after everyone has had a turn, the Facilitator returns to any points of conflict or controversy. The team discusses, as briefly as possible, nuances or differences of opinion. For Engagement Sessions lasting 30–60 minutes, the hot wash shouldn’t take more than 15 minutes, even with a full contingent of team members.

Changing the Artifact or the Script

Changing the Artifact

After the hot wash, the team needs to decide what, if any, changes need to be made to the artifact and/or the script. There are several reasons why the team would make a change:

1. The stakeholder was so confused by something in the artifact that the session was delayed significantly. Depending on the severity, the team may want to fix the artifact to avoid the same issue in following sessions.

2. The stakeholder made a change to the artifact during the session and it now represents a change to the assumptions. The team has a choice: Keep the change or keep it in mind for future sessions and restore the artifact to its original condition. Some changes open a new line of inquiry, exposing something exciting.

3. Saturation: The stakeholder identified nothing new (compared with any of the prior sessions). In this case, the stakeholder has trod the same ground as others, at least with respect to some aspect of the artifact or script. The team may change the artifact in service of additional assumptions or to approach the same objectives in a different way.

No changes should be made after the first session. The team doesn’t have enough experience to know whether the first stakeholder’s reaction is a common case or idiosyncratic. If after several sessions the same sticking points come up, it is time to consider a change. There’s no value in covering familiar territory.

Changing the Script

If the team feels it hasn’t heard enough consensus from prior stakeholders, there’s no harm in leaving the artifact intact but shifting the script. When the controversial point comes up, we let the stakeholder pursue whatever direction he thinks he should go, and when he’s finished, we offer an alternate consideration based on what we’ve heard others say and do. We frequently say, “Cool. There’s an interesting difference of opinion going on and we’re curious what your thoughts are. You’ve said the skaxis process would result in you knowing more about its operating conditions, but others have said the skaxis process isn’t really the interesting part. For them, it’s the loodoxle process that’s likely to occur here. We don’t know much about what you’re doing, so it all sounds great to us. What do you think these other folks are talking about?” It’s amazing what you learn. The stakeholder may provide all sorts of interpretations that are completely at odds with what he had first offered, which provides even more opportunity for conversation.

The Cold Wash

After all sessions are complete for the day, the team should find a quiet place, perhaps a conference room in the hotel, sit back with a beverage, and go through the salient points of the day. Each team member will remember something slightly differently from the hot washes. Commonalities among the sessions will appear, as will key differences.

As the team collects these thoughts, they need to consider whether to take action on any of them the following day. Are there key points of confusion the next stakeholder could clear up? Should the artifact be changed or returned to its original form? Is the sequence causing a problem? Should the tasks be switched up? It’s better to course correct in the middle than come back from a multiday research effort with impoverished results.

But Really, When is Enough Enough?

As with each individual session, there comes a time when the team needs to decide whether it’s worth proceeding with any more sessions at all. As we’ve said elsewhere, there are three reasons to stop any further Engagement Sessions:

1. The team has run out of time. Obviously, this doesn’t apply if there are still sessions to complete. But if the team has finished a round of sessions and its deadline is looming, they’ll have to stop wherever they are.

2. The team has run out of resources (money, stakeholders). In this case, the team can’t afford to go back out to do further sessions due to budget or people constraints.

3. The team stopped learning new stuff. After the most recent session in a handful of sessions, the team heard nothing even remotely new. It’s time to stop, reconnoiter, and figure out if changing the artifact, script, or types of stakeholders would drive more learning.

When the sample is purposively designed for maximum variation, patterns may not emerge for several iterations. Common themes appear to emerge within the first several sessions, but just as the artifact is presumptuous, so too are these initial thoughts and themes. We shouldn’t believe them quite yet, even though we keep hearing them over and over. Test these thoughts and themes with the next stakeholders (if they don’t mention them spontaneously). As with the conflicting interpretations mentioned in the Section “Changing the Script,” it’s perfectly acceptable to raise a previously heard common theme with a new stakeholder to understand it in her context. After we have heard a pattern three times across our sample, we reduce our skepticism; after five instances, we stop investing time in it and move on.

Summary

PrD comprises two parts: the Creation Session and the Engagement Sessions. Much like any other social science research involving interviewing people, the Engagement Session requires attention to detail.

• Create a “purposive sample;” specifically we recommend a “maximum variation” purposive sample. When the team’s assumptions resonate with stakeholders having a wide variance of attributes, the team increases its confidence those attributes don’t matter.

• Recruit stakeholders from a variety of sources, but remember each has its bias: Sales teams, support call centers, social media, and user groups may not overlap with the purposive sample characteristics.

• Although running sessions remotely sounds attractive, in our experience it is a siren call. The benefits of face-to-face engagements are far greater than the cost of travel.

• Almost all of our Engagement Sessions are with one stakeholder. Under some circumstances, we’ve benefited working with two stakeholders simultaneously.

• The session is over when we’ve achieved our objectives, time has run out, or the stakeholder says it’s over.

• Capture themes, ideas, observations, and insights as soon as possible after the session in a “hot wash” critique. If there are many sessions in a day, allow for time between them to collect thoughts and set up for the next session.

• The artifact and the script are subject to change at any time it benefits the team to do so. If we’ve stopped learning, or we consistently run into trouble in the same place, we change things up to improve the likelihood of success in future sessions.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.