Appendix A

The Cases

Challenging Research Protocols/Social Innovation

PrD can be used to explore problem spaces in a wide variety of contexts and settings beyond product or service development. The cases in this section illustrate PrD’s use for a wide range of goals: from social innovation in Englewood, Illinois, to rapidly capturing rich anthropological insights in Ghana. Two additional cases highlight PrD’s flexibility: the design of a game to learn about Chicago residents and the design of workshops for teaching PrD.

The Case of Constricted Collective Conversation

The Resident Association of Greater Englewood (R.A.G.E.) had a challenge. The residents of this south Chicago neighborhood were not coming together as a community in ways that enabled them to tackle complex social problems as a whole: Crime rates were high, civic engagement was low, and neighbors didn’t trust the city establishment (and oftentimes each other). R.A.G.E., a group of hypermotivated residents determined to change the dynamics of the neighborhood from the inside out, partnered with a team of six graduate student designers from the Institute of Design at the Illinois Institute of Technology to find more sustainable ways of reaching out to their neighbors and improving resident engagement. For six months, Maggee Bond, Diego Bernardo, Amanda Geppert, Alisa Weinstein, Helen Wills, and Janice Wong worked closely with Asiaha Butler and Latesha Dickerson of R.A.G.E. and other local organizations and businesses to explore opportunities.

R.A.G.E.’s process for convincing people to attend meetings—knocking on doors and putting out fliers—didn’t scale. Meeting attendance remained confined to a small number of familiar faces and motivated neighbors. Together, the designers and their community partners posed the question, “Could design be used to engage a broader cross-section of the community?” How might design provide a more expansive set of tools or methods to improve R.A.G.E.’s outreach and engagement goals?

Adding to Englewood’s intrinsic challenges of low engagement is its reputation for being one of the most dangerous neighborhoods in Chicago. As a high-profile community, it attracts a lot of well-intentioned offers of help. But historically such projects fail. This is because they fail to take the broader context into account.

The team wanted to stay contextual to the problem space. They figured if they and R.A.G.E. understood the problem space in a broader way, together they could identify better ways of improving neighborhood engagement. They also had a constricted time frame and decided PrD was right tool for the job. The team understood PrD (or “provotyping,”1 as they had come to know the process) was a key method for staying in and rapidly exploring the problem space of the design challenge at hand.

PrD made sense in another way: The team was under time pressure with its academic schedule; they had to move fast. As Alisa said, “People spend their entire academic careers studying communities like Englewood. We couldn’t do that. We just had to start.” One of their initial ideas centered on this question: How can we create good news and spread that instead of always having bad news and negative rumors circulating about Englewood?

After collecting information and best known practices from a variety of sources, the team got started, forming their first assumption: People in Englewood weren’t talking to each other. Because it was a highly territorial neighborhood (defined by the block on which one lived), neighbors had little trust of others. Although there were many platforms for information sharing in the community, it seemed these were not the best channels to facilitate engagement.

The team established a second assumption: Their approach had to be “real world,” not digital. Only half of the residents had access to the Internet. This came with its own challenge. Englewood also had few physical spaces at the time, such as coffee shops or sit-down restaurants, to use to engage with people face-to-face in an everyday context.

These two operating assumptions, a lack of trust and a lack of physical space to bring people together, drove the first provotype. The team considered what sorts of artifacts they could introduce into Englewood to increase their understanding of neighbor’s concerns and to learn more about the community.

Several other assumptions drove the team’s consideration. They wanted to avoid the insider–outsider dynamics often present in an interview setting. Historically, previous researchers had used one-on-one or group interviews, but residents might have viewed those negatively. Such engagements might set up a power dynamic that could skew conversation. Recruiting participants through community groups or letting people self-select would likely run into the same problems R.A.G.E. had run into: The same activists would show up.

Their objectives were simple but challenging: What do the residents of Englewood consider positive engagement to be? What forms of engagement would they be interested in and willing to undertake?

The team relied on PrD’s principles of Iterate, Iterate, Iterate! and The Faster We Go, the Sooner We Know. Alisa comments, “We got out there and started trying things. We deployed the artifacts in three phases.” In the first phase, educators, students, parents, and residents were offered a “message board” on which they could leave anonymous sentiments. The sentiments shared on the walls and boards reflected optimism and hope. The team wondered, after analyzing the data, whether the context of the event affected the tone of the responses. How might a more public environment affect such sentiments?

For the second phase the team offered residents two types of artifacts. The first was a large Candy Chang–inspired prompt wall2 they installed on a street corner at a busy intersection. At the top of the board it said, “I’d like others in Englewood to know …” (Figure A.1).

Figure A.1 Community member of Englewood using a presumptive chalkboard to engage in conversation

The second artifact was a set of paper books with the same statement on the cover, placed with local store owners and community spaces (Figure A.2).

Figure A.2 A page from the paper book distributed throughout the community to elicit community conversation

While these two artifacts were, in many ways, Participatory Design elements, they became PrD by how they affected the team’s understanding of the problem space. Each artifact generated very different responses. The chalkboard solicited bolder, less filtered statements, pleas to stop the violence, distrust of police, etc. The books elicited stories. People shared stories from their past, their hopes, and their dreams. But the key reason these artifacts became PrD was how they affected the team’s understanding of the community, merely through the artifacts themselves (not just from the content each elicited).

In the case of the chalkboard, each side was filled by the end of each day, requiring it be cleaned off nightly. While erasing the board afforded the team an opportunity to interact with curious neighbors who might have not participated, it generated significant negative reactions as well. Twice, a concerned resident rushed over demanding to know why the team was erasing what people had written. This demonstrated the community felt a sense of ownership over the board (one of the team’s initial goals) and confirmed one key assumption: the community’s distrust of researchers.

Alisa confesses, “While we had photographed the board before erasing, we hadn’t posted the photographs immediately, ultimately posting them after the chalkboard had been torn down (perhaps by someone disenfranchised by the process). This lag was an oversight and significant failure of our protocol. While unintentional, the lag time shined a light on the community’s deep concern about ownership and lack of transparency from outsiders.”

In the case of the prompt books, a very different dynamic emerged. The store owners liked the books. One owner, seeing the book had been filled with writing, asked for another to replace it. The mere presence of the book began to drive a very different dynamic (albeit small) within the places it was located.

Phase three was a Participatory Design workshop in which the team shared the results of the prior PrDs and a potential engagement framework for the attendees to use.

Alisa states the team couldn’t have learned as much as they did about Englewood using another method. R.A.G.E. continues to use some of these tools today, suggesting they made a real difference in helping neighborhood activists expand their outreach efforts, certainly a key goal of the effort. The artifacts, or provotypes, gave the team insights into the community that would have been awkward to tease out by simply talking with people. An artifact, after all, is not a set of eyes sitting across a room judging you.

Alisa concludes: “PrD is useful for social innovation in that these can be very sensitive projects that could easily go wrong. You could easily alienate people and lose their trust. Once that happens, that’s pretty much the end of the project. PrD gave us a way to test our assumptions about citizen engagement and helped surface implicit attitudes and belief systems in a way direct conversation could not. With each iteration, the landscape of what we needed to understand to build the right set of tools became more and more clear. It also provided a means of involving a much larger cross-section of the community.”

The Case of the Black-Magic Batman

When Evan Hanover and Anne Schorr, as part of Conifer Research, went to Ghana on behalf of their client, they had two goals: contribute to the global fight against malaria and understand sub-Saharan market economics. Essentially they had one key question their client was keen to answer: What does a person need to know to build a sustainable business there?

Conifer discovered children, through schools and their older siblings, along with their early participation in work, are important conduits in the community. As a result, Conifer decided to do a session just with kids. They had no idea what they were going to learn.

Conifer focused on the kids’ chores and responsibilities, such as hauling water. In some cases they have to travel a kilometer or so just to get water for their families. What did they think about these responsibilities? Conifer had them draw and talk about their favorite parts of the village. Because the researchers were a novelty, the kids were excited to talk to them. They were excited because Evan and Anne wanted to talk to them, to listen to them. The kids, Evan told us, were superengaged, happy and having fun with the exercises.

In the next part of its engagement, Conifer reflected with the kids about the things they do. “You go to school, fetch water, help with the food, help make bread, gather firewood, harvest grains and so on,” Evan recalls. The researchers separated the kids into groups of four or five, turning their desks to face each other, and they handed out action figures to each of the groups. Evan continued, “We said, ‘You guys do all this stuff and some of it’s really hard, so let’s imagine you’re a super hero and you have a super power to change all that.’ ”

There was general confusion and discomfort. The feeling in the room shifted drastically. Where it had been fun and the kids were fully engaged with the notebooks and the drawing, there was now silence and avoidance. Not only was the American notion of superheroes completely foreign to these children they understood “super power” to mean black magic.

Naturally the kids shut down when faced with the prospect of wielding evil. Eventually, after the team realized their error, they reframed the exercise, asking instead, “What if you were President” or “What if you were the village chief?” When the kids heard these revised prompts, Evan said, “They were like, ‘Oh, yeah, water should just be brought to people’s houses.’”

Evan and the team had made some assumptions about the protocol they were using to work with the village children. Those assumptions were wrong in ways they couldn’t begin to predict. But the key point is that in spite of a massively erroneous assumption, or perhaps because of it, the team learned wonderful things. As Evan put it, “We learned that, as much as modernization is taking place in West Africa—you know everyone has relatives making profits off the natural gas boom or has seen international brands making it into the village—there are these traditional ideas that are still so ingrained in the children.

“It really drove home for us how much we needed to gauge the combination of tradition with the influx of the modern world. It helped frame up how to talk about aspirations and the future. What are the agents of change? Traditional healers and witches are possible loci of change. That was one of our big learnings and tenets that had been brought out by this failure, something that really wasn’t exposed by speaking with the adults. Adult members of the community we had spent time with for two or three days never really addressed the spiritual side of things. There seemed to be a sensibility that Westerners wouldn’t appreciate it, so we only got that insight from the kids. This was really important since we were wanting to influence their beliefs and practices having to do with healthcare. It changed how we looked for pitfalls.”

This key failure with the team’s research protocol led to deep insights into the way change is accommodated by village culture. It opened up pathways for establishing trust and authority. The deep integration of the supernatural in village life (exposed by the team’s gaffe) gave the team ideas about how to introduce innovation and unfamiliar Western notions. Without acting on their assumption, and quickly identifying the results of their failure (i.e., without employing PrD), Conifer is convinced they would have missed key understandings, or taken much longer to realize them.

The Case of the Preoccupied Passersby

The city of Chicago was looking for help from its citizens to plan for the future of the city’s arts and culture. Enter Jaime Rivera and his team (Lauren Braun, Kareem Hindi, Lee Lin, and Jose Mello), five graduate student designers from the Institute of Design at the Illinois Institute of Technology. Having learned about provotyping from professor Anijo Mathew, they were ready to offer the method to the Chicago team. They began by building participatory games to capture people’s behaviors and preferences for arts and culture (Figure A.3).

Figure A.3 Examples of participatory games designed to uncover time frames for engagement with Chicago residents

Within a week of fielding the low-fidelity games at Chicago City Hall, the team had learned that Chicago residents could be expected to spend only an average of 10 seconds at the installation before moving on. They also learned that participants liked to see the contributions of others before contributing themselves and that they preferred games requiring and rewarding self-expression. The primary benefit of running these quick provotypes was how rapidly the team gained these insights, all without building a complete installation. This enabled them to quickly set up the real installation, better positioned to succeed.

The outcome was “SkyWords,” an interactive, dual-screen game set up in Chicago City Hall (Figure A.4). On one screen, passersby answered questions related to Chicago music, food, art, and community. For example, “Do you prefer Chicago have more hip hop, jazz or rock-and-roll?” Residents answered questions by inflating the digital balloon that contained the desired answer. To inflate the balloons they used a physical bicycle pump, pinwheel, or bellows. Once inflated, the digital balloon with the selected answer floated up and off the first screen. It would then drift down on the opposing screen, where other stakeholders could take aim and pop the balloons to reveal fellow Chicagoans’ answers and preferences.

Figure A.4 SkyWords installation in Chicago City Hall

The SkyWords installation engaged more than 2000 people who answered nearly 2500 questions in 10 days. The game was a complete success, creating awareness of and generating data for the 2012 Chicago Cultural Plan. The plan will direct the city’s development of arts and culture for the next 10 to 20 years. By using PrD (in the form of provotypes) the team was able to quickly identify the key design criteria for the actual installation, greatly improving its chance for success.

The Case of the Pushy Pillboxes

On two related occasions, the CHI2004|ICSID Forum3 and SEC05 (an in-house technical conference at Sun the following year), Leo first tested the notions of PrD.4 In collaboration with his sister, Nancy Frishberg, and others, Leo explored a key question: To what extent would designers rely on PrD as a means of user engagement and research?

In the first instance, the team fielded a two-day workshop with 40 participants from different countries, industries, and roles: from human factors engineers to usability engineers to makers. The second instance was a single day, with attendees from outside of the usability or design professions. The overarching intention of both was to bring together professionals of all stripes to explore collaboration across disciplines. PrD was a method to ensure the attendees’ engagement.

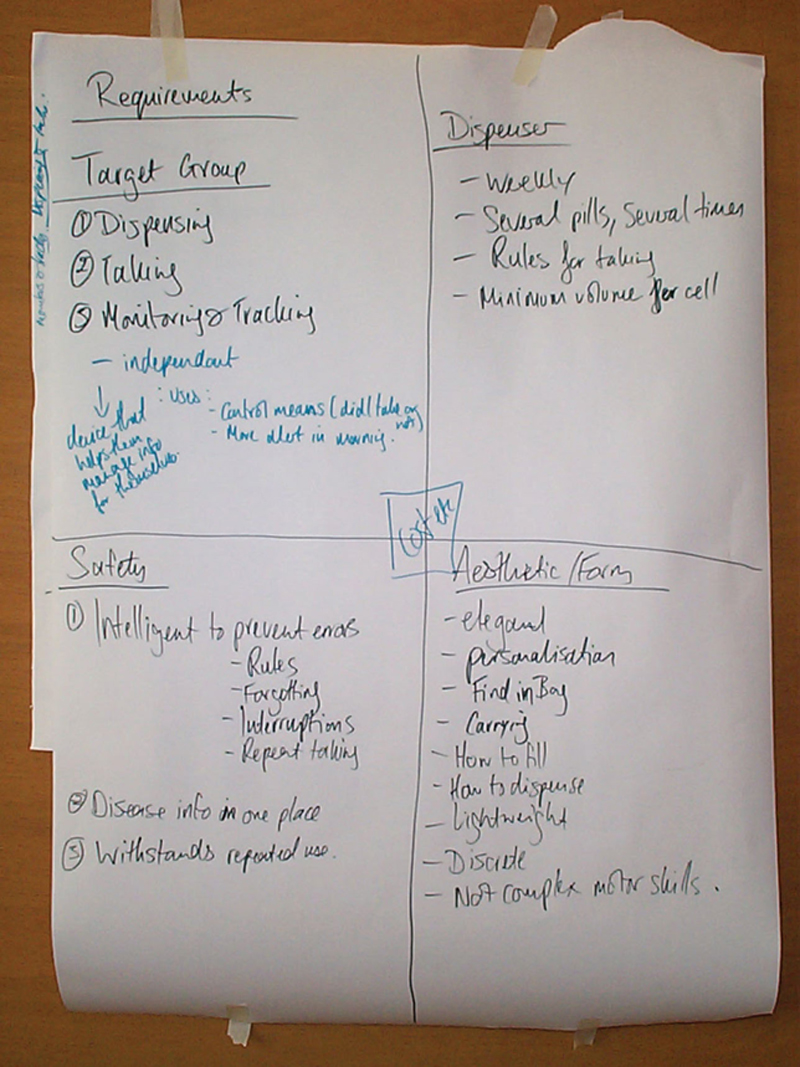

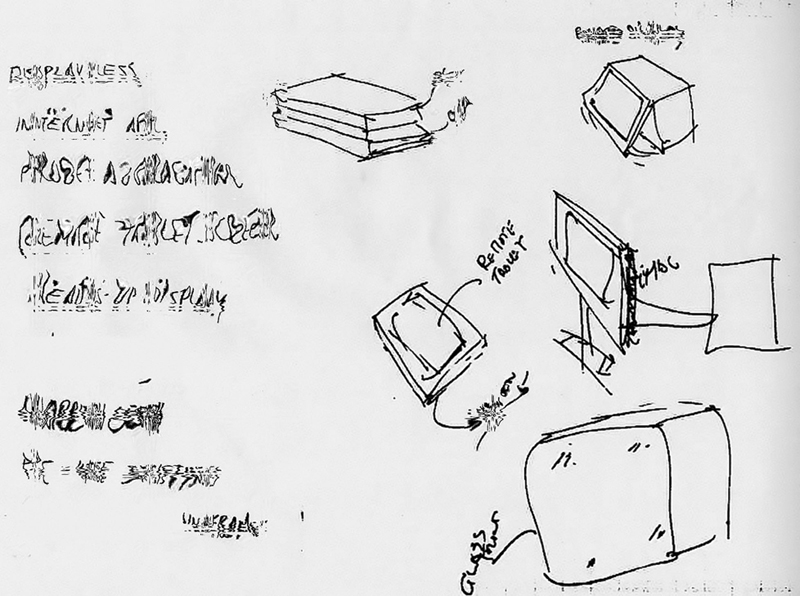

Both workshops were structured identically, becoming themselves prototypes for PrD as Leo fielded it in subsequent years: a Creation Session and an Engagement Session with real users. In both cases, the real users were elders in assisted living situations and the design problem was an “intelligent pill dispenser.”

In the first occasion, PrD was not a requirement. Leo’s hope was that the teams would get the hint: As they were crafting prototypes in advance of their user engagements, he had hoped they would take the prototypes along. He made no effort to force the issue, letting the situation act as a natural laboratory. What he and his collaborators observed was a fascinating difference among the attendees in their approach to solving the problem. The designers immediately began crafting artifacts, sketching, and exploring potential solutions to the brief (Figures A.5 and A.7). The usability professionals focused on decomposing the problem through whiteboarding, crafting matrices of attributes, and other analytic work products (Figure A.6). By the time all of the teams were loaded onto the bus to visit the assisted living facility (“Vienna Haus”), only one team had a physical artifact to offer the end-users.

Figure A.5 Industrial designer crafting intelligent pillbox prototype from clay and sketches

Figure A.6 Usability Researchers identifying qualities of the desired experience for an intelligent pillbox

Figure A.7 Sketch ultimately leading to a physical prototype for a pillbox

In the second occasion, teams were required to use an artifact to elicit user reaction. Leo’s intention was to learn to what extent teams would benefit from using the PrD process. In service of that objective, the organizers presented the process as part of the introductory material and facilitated the crafting of artifacts during the Creation Session.

The lessons learned from both engagements were strikingly similar: Even when they had an object to offer end-users, teams failed to offer it for use. Instead, teams treated the object as a prop for demonstration, explanation, or presentation. In fairness, the objective of the workshops was to build collaboration among the participants, not to focus on PrD as a method. As a result, teams relied on the processes they knew well, such as user interviews or the presenting of artifacts, in service of discovering users’ needs.

Vienna Haus was striking in several ways. Imagine 40 professionals, of whom only a handful spoke German, arriving at an assisted living facility in which very few people spoke English. Imagine joining the residents (all women, none of the men wanted to play) in their community room—two of them with eight team members—and no one quite certain how to proceed. Almost all of the teams fell into typical user interview protocols, asking questions about the women’s approach to medication, frequency of taking pills, and so on. Even in the case of the team with an artifact, they offered it for presentation. Imagine the teams’ surprise and shock when the women dismissed most of their attempts and instead suggested everyone just get up and see for themselves what they did with their medication. Within 30 minutes, they were demonstrating their own pillboxes, explaining their comfort (or perceived comfort) with them and the attributes they held dear (Figure A.8). The session transitioned into a more ethnographic engagement: Residents told stories, demonstrated their artifacts, and offered tours of their context.

Figure A.8 Vienna Haus resident offering her pillbox (with remarkably similar attributes to prototype in Figure A.7)

In the SEC05 engagement, the results were more complicated. Because the teams weren’t comfortable offering their artifacts for use, the end-users acted as clients responding to a design pitch. Since the end-users hadn’t asked for a design pitch, they treated the engagement as an opportunity to critique the artifacts. The teams experienced several of PrD’s risks that day: focus on the artifact instead of the assumptions, the need for expert facilitation, and, most importantly, a need for deeper interpretation of the users’ critique.

In both cases, team members reacted differently to the end-user responses based on their profession. In general, designers were dispirited by what they heard while the usability professionals were delighted.

Because of the nature of the workshop format, teams were focused on designing a solution (as opposed to understanding the problem). They were on a mission to craft a design by the end of the second day, and the designers felt they had to start over. The usability folks were elated by capturing real-world needs and in-context data, but they too were concerned about how little time the teams would have to actually use the data in the design.

In the second case the designers focused on the critique of the artifact, using that feedback to reconsider their design, whereas the usability professionals interpreted the critique as insights into residents’ needs.

For Leo, the results were revelationary: Nobody made the leap of crafting an artifact in service of their research! PrD was neither a commonly understood approach (as evidenced by the first case) nor intuitively obvious (or successfully applied), even when it was explicitly required (as evidenced by the second case). With the exception of the SEC05 results, in which usability professionals gleaned useful data from the residents’ critique, none of the teams experienced PrD’s primary advantages: using artifacts to provoke responses to their assumptions, teasing out end-user mental models, or inspiring visions of disruptive innovation through cocreation and engagement.

Indirect Artifacts

PrD relies on artifacts to elicit reactions from our stakeholders. But the artifacts do not need to be concrete expressions of a product or service, as several of the cases illustrate. This section includes two additional cases along these lines: artifacts that have nothing to do with a product or service per se. In the first of the two cases, the artifact is a series of provocative statements in a PowerPoint presentation. In the second, the artifact is a carton of plastic eggs!

The Case of the PowerPoint Play

From 2005 to 2008, when Steve Sato was part of HP’s corporate design organization, he and his team were responsible for building the experience design capability across the company. In part, his mission was to help the Vice President of Corporate Design develop presentations to other executives.

The team utilized the presentations to perform PrD, using them to learn about the VP’s attitudes and mental model of design, designers, and the role of design within the organization. In turn, through the VP’s feedback, the team learned about other executives to whom the VP was presenting.

The process was straightforward and simple: They threw together draft presentations and worked with the VP in a weekly meeting. The team’s objective was to assess how well their vision and aspiration for design would resonate with both the VP and the other executives he presented to. The specific “artifacts” were exploratory statements purposefully and strategically placed in presentations to gauge the VP’s reaction to the slide. Through this ongoing process of provocation, the team learned how far the VP was willing to commit or what he was willing to show management.

No matter his reaction, the team would always ask him “Why?” Through this conscious process the team gained considerable understanding about his thinking on the positioning of design in the organization. By testing their assumptions first with the VP, Sato’s team was able to reduce the risk of their vision being too outlandish for the rest of the company. They discovered, for example, the VP was uncomfortable suggesting to the Chief Marketing Officer (CMO) that they take over similar work previously done by other design teams in different business units. Instead, the VP thought it better to show executives what the issue was with the three design teams doing similar work, suggesting to them it was wasteful. If the VP got pushback when pitching the example to other executives, he could leave it at that. If they were receptive, he could go on to disclose more about his strategy for having corporate design take on the work.

Working with the VP in this way, the process revealed important information about the CMO’s concerns and thinking. He was interested in the strategy but concerned the corporate design team’s charter was becoming too broad too quickly, suggesting the CMO did not want to support further expansion of corporate design at the moment.

The team extended its use of PrD to almost all its engagements with executives to gauge attitudes and positions. For any specific initiative, the team would offer facts and a recommendation (as a provocation), keeping alternatives ready in their back pocket. If an executive pushed back, they would ask “Why?” and then bring out the alternatives.

The team used this provocative approach methodically. After each session, they plotted their understanding of key individuals’ thinking using stakeholder position charts. By provoking their responses in methodical ways, the team was able to predict future interactions, improving their presentations and positioning with each subsequent iteration. As Steve says, “We were advancing design as one would in a political campaign. Say you have 40 people you need to influence. You need to know where in three to four different groups with similar needs each person stood. In our case, this PrD approach really helped with organization change.”

The Case of the Hard-Boiled Eggs

In 2013, Leo and his team of designers were asked to improve collaborative work models for their employer’s engineering teams. A major part of the effort was identifying and agreeing on the term “collaboration.” Another significant part of the effort was understanding the current work models used by various teams. Once the basic workflows were captured and the team had an agreed-upon definition of collaboration, they turned their sights on designing potential solutions. For several weeks, team members engaged in several rounds of PrD with end-users, teasing out assumptions, testing their understanding from the initial research, and trying to validate key concepts around collaboration.

At around this stage in the project, the system architects revealed where they were heading: The collaboration capabilities would be available as separate functions or components. Although this made a lot of sense from a system design perspective, it didn’t necessarily align with the team’s understanding of the work models, the results of the PrD engagements, or the working definition of collaboration that had been forming.

Still, the team was able to rapidly sketch several concepts, each assuming some kind of component-based collaboration framework—essentially diagrams with titles. But Leo could sense the team was getting ready to do a deep dive into design development. He estimated the effort would take at least a couple of weeks before they would have enough definition to really understand the differences among the initial concepts. He expressed his concerns to the team lead: “Why are you going to take any more time with design development, especially since we don’t really understand what users would expect of such a componentized experience?”

“Well,” the lead explained, “how are we going to get them to give us feedback if we don’t have wireframes or some kind of design?”

“With a PrD,” Leo recalls stating with a certain amount of smugness.

“Right,” the lead retorted. “That’s what we’re trying to do. But we’ll need to get wireframes together.”

Leo threw down the gauntlet: “I could do that test with a carton of hardboiled eggs” (Figure A.9).

Figure A.9 A carton of plastic eggs used to elicit reaction to a componentized experience

The lead recoiled in surprise, uncertain if Leo was pulling his leg or serious. “But…” he sputtered, realizing Leo was dead serious, “but won’t they look at us as if we’ve grown a second head?”

It was at this point Leo figured out he might need to write a book, since the team lead hadn’t really comprehended PrD, even after fielding several sessions in the prior few weeks.

Leo went on: “The key thing here is we have a very strong operating assumption coming from our architects: that somehow componentized collaboration is a good thing. Are you convinced it’s a good thing? Can you predict how our users will react to it? Will they even understand such a thing? Why bother crafting anything with a screen if we can’t be confident in their grasp of such an approach?”

The team lead couldn’t imagine how to proceed without further design effort. At this point the team’s UX Researcher called Charles, who (unbeknownst to her) had already spoken with Leo about the exchange he’d had with the team.

After explaining the research problem she asked, “How would you research this?”

“I’d use hardboiled eggs,” he said on the phone.

The researcher laughed and said, “Yeah, funny, but that’s really not funny.”

She was, however, intrigued by the seemingly absurd suggestion and took the challenge. Oddly, another of her team members had a whole box of plastic Easter eggs in his cubicle that he immediately offered her. (Leo denies knowing his team members kept such artifacts handy.)

Within three days the researcher returned with results, many of which were surprising.

As external stakeholders (users) played with the labeled plastic eggs (Figure A.10), some amazing things happened. The users clustered their components naturally, that is, without any prompting. The users gathered up the capabilities and began grouping them in the carton. Every one of the participants did this. In reviewing the protocol, including the script, there was nothing apparent that would have suggested the users were being asked to cluster the capabilities. They all just did it. The researcher hadn’t predicted that would have been a desired or expected outcome when she went in. The team was focused on how a user would interpret an isolated, componentized capability.

Figure A.10 An Engagement Session with the eggs. Note how the individual selects specific eggs and sets them aside on the plate

Users also expected their cluster to behave, in sum, with greater capability than the individual components. In all cases, after participants put their clusters together, they spoke about them as if they were part of one application. Work done in one capability was expected to feed into, show up, or somehow be a part of another capability.

The point here is that with a minimum of preparation and artifacts, a single team member was able to complete the pilot the same day and complete six external stakeholder engagements within a couple of days. The results, some profound and others less so, had significant implications for the design of the experience (the team made several adjustments to their concepts as a result of the findings).

Further, the team was able to help prepare the architects for several elements in the system they may not have anticipated but which would be required for users to accept the solution. If they hadn’t learned about the user expectation to interoperate among the capabilities or the need to cluster them in defined ways, the system may not have been robust enough to deliver on the users’ expectations.

PrD Serving Business Results

The fundamental aim with PrD is to expose and vet team assumptions to explore a project’s problem space. In addition to several cases already offered, in which the problem space was ill-defined, the case in this section focuses on exposing and vetting business assumptions. This case reveals the benefits of PrD to align internal stakeholders on their assumptions about a business opportunity. Although it uses a direct artifact for a proposed service, the findings from the PrD sessions assisted the business team in understanding their intended market. Perhaps most dramatically, the process revealed deep divides in the team’s operating assumptions, in spite of working together on the project for over a year.

The Case of the Business Case

With the help of a market research firm, Leo’s client had identified a compelling market ripe for a disruptive new business model. Part of the solution the team had sketched out included a technology “stack” involving cloud storage, data analytics, and a browser-based front end. At the point Leo engaged with them, the team had developed a “proof of concept” of the lower levels of the stack and was hoping to develop a prototype for the user interface.

Their intention was to continue exploring the business value of the idea by shopping the concept with prospective customers and partners at tradeshows. Time and money were short. After a couple of meetings with the team, Leo suggested they could make better use of their funds in the time they had to pursue a PrD rather than craft a UI prototype.

Leo offered three reasons to go with PrD:

• The team had dozens of assumptions about the business plan they hadn’t had a chance to vet. Building a UI prototype would do little to address their business assumptions.

• The team had identified (but not developed in any detail) at least eight personas who would be key to their success. PrD could help the team build their personas, whereas building a UI would do nothing to better understand any of those personas’ needs or influence on the business idea.

• They already had a PrD artifact: The market research team had crafted a PowerPoint deck illustrating the business concept. It was just a matter of getting it in front of the right stakeholders.

The entire process from the moment Leo first met with the team to the final report took less than three months. Leo facilitated a mini-Creation Session, bringing in designers to supplement the team. Because the client already had an artifact, Leo focused the team’s attention on their objectives and tasks for the Engagement Sessions. They decided on two basic tasks: the persona’s use of an out-of-box functionality and the persona’s selection process for the equivalent of an “app store.”

The PowerPoint deck was not appropriate for the team’s purposes: It didn’t permit users to actually work with the concept. Instead, the group crafted a paper prototype with an “out-of-box” display (Figure A.11) and an “app-store” display to support the two tasks. Within two weeks of the Creation Session, several team members (Leo, a Facilitator, the product manager, and the technical lead) were in front of end-users with the artifact.

Figure A.11 One of the artifacts used to test the business case for a new service

The results astounded the team. Within a few hours, after working with only a few end-users, patterns began to emerge:

• The solution had to have an out-of-box experience that differed dramatically from what the team had assumed during the Creation Session. User expectations for that experience had significant impact on the technical stack. Additional systems and data needed to be integrated.

• The business idea was indeed revolutionary. Although this finding may have been trivial given the market research, it served to validate the direction the team was heading. But of greater consequence was the negative prospect of such a revolutionary idea. Users were completely befuddled by the business value proposition! The elements that made the idea revolutionary were so fundamentally foreign to the prospects that if the team expected to deliver it in its current form, the venture would struggle.

• Users revealed key requirements the team would need to satisfy in the sales process itself. Even if the disruptive business model could be communicated to the end-users’ satisfaction, the ecosystem in which they operated demanded the team engage with many other players before the solution could be purchased and installed.

But one of the most profound insights came after the team returned from the Engagement Sessions during a “cold wash” debrief. There, with the Facilitator, lead technologist, product manager, and Leo, the group reflected on what they’d learned the prior week. The product manager discussed how unusual it was for the users to not recognize an “app store” as an experience, given how pervasive app stores were. He also noted the users were unwilling to accept the apps’ price points, which he assumed was based on their unfamiliarity with the proposed business model. It was at that point the lead technologist stepped in and expressed his own concerns about the business model, suggesting he had never intended to price or size the applications as the PrD had proposed!

What makes this so surprising and profound is that these two individuals had been working on this project, together, for almost a year. In addition, both were present and engaged at the Creation Session, in which these assumptions were clearly articulated and discussed. PrD revealed an unresolved tension between the product manager and the technologist. It was as if the process accelerated the time frame of product development, forcing them to confront a key business decision much earlier in the venture than they would have otherwise.

Although they had both been aware of the differences of opinion about the pricing model, PrD brought it to the table as a fundamental issue they needed to resolve.

Using Real Products as Artifacts

As discussed in Chapter 8, while iterating in the problem space of a project it’s generally best to stay with low-fidelity, low-investment (in terms of time, effort, and money) artifacts, speeding time to insight and minimizing insight overhead. One of the least expensive artifacts is to use the stakeholders’ existing products or services, illustrated in The Case of the Pushy Pillboxes (mentioned earlier in this Appendix). The cases in this section go the other route: crafting highly resolved prototypes. As these cases show, a high-fidelity, working system provides substantial benefits to the team beyond exploring end-user needs (e.g., understanding the system components or technical challenges). But these cases illustrate the basic tenet of PrD: Is the team’s approach satisfying key issues in the problem space? In both cases, the teams realized the artifacts were far more resolved than required to uncover key problems faced by their stakeholders. In spite of this, one of the cases demonstrates that offering up a high-fidelity artifact can lead to rich insights of the problem space.

The Case of the Rx Reminder

Working with a large software vendor, Janna Kimel and her team focused on the problem of how best to remind seniors to take their medications. Twice as many people die each year due to nonadherence to prescription medications than die in car accidents. The key question her team intended to address was what could industry and technology do to help?

The team focused on the notion of “contextual reminders.” They recruited 10 individuals in their 60s and 70s who agreed to try three different form factors, each for a week. The order of the form factors was counterbalanced. One was a smart pillbox with a visual reminder. It was magnetized so stakeholders could place it anywhere in their home or car. Another was a smart pillbox with a mobile audio reminder. The third was a smartwatch with audio and visual reminders (Figure A.12).

Figure A.12 A smartwatch as Rx reminder system

Aspects of this study were very much PrD, in that the team was testing their assumptions about these users’ needs for medication reminders, the underlying drivers for why people fail to take their medication, and specific beliefs about technological approaches to the problem. The study, however, diverged from PrD in two key ways: The artifacts were functioning prototypes and the data collection protocol included indirect methods (personal diaries and data logs from the devices themselves).

The reliance on actual, functioning technology introduced significant complexity into the study. One of the first things the team learned was it couldn’t expect the participants to understand all of the technology involved in the solution. The smart pillbox, for example, had to communicate to a laptop that was also placed in participants’ homes. In one case, a participant loaned the laptop out to her son and the team stopped getting data. In another case involving the smart pillbox, one person didn’t like how the activity beacon (used to track when the participant was moving around) looked on her wall. She hung a puzzle box cover over it so she could look at that instead, rendering the motion sensor useless for a period of time.

One of the biggest assumptions the team had made involved the seniors’ mobility: They were much more mobile than the team had assumed. With the smart pillboxes, for example, the reminder was mobile but the pillbox itself wasn’t. Just because stakeholders had the reminder with them didn’t mean they were near the pillbox! One participant reported she’d completely forgotten to take her meds because she and her daughter had decided to take a long walk. Another apologized for missing an interview, saying, “I was on a raft.” The team’s big assumption was that the seniors would be sedentary enough to always be near a stationary pillbox. They weren’t. The reminder and the pills needed to be together, as these people were highly mobile.

As the study was conducted in stakeholder’s homes, it revealed much about their current practices for reminding themselves to take their pills.

One man had his pill bottles in a row. He would turn them all upside down. When he’d take a pill he’d turn that bottle right-side up, providing himself a visual indicator of which medications he’d already taken that day (Figure A.13). One stakeholder said, “At 11:00 we play Yahtzee. After Yahtzee I take my pills.”

Figure A.13 Stakeholder demonstrating his system of remembering which pills he’s taken

There was a woman who was taking care of her sister, trying to keep her in independent living. Her pills were arranged like an altar in front of a picture of her grandchild. Whether done consciously or not, the arrangement created an emotional connection: It’s important to take this medication so she can be around to see her grandkid grow up.

Janna’s team completed the study with a Participatory Design exercise in which participants were asked to craft their own vision of a reminder using Play-Doh. Even though they created artifacts looking like a much simplified version of the watch, it wasn’t the form factor that mattered as much as the underlying assumptions it embodied. As Janna tells it, “When they described what they’d fashioned out of Play-Doh, it became apparent they’d only fashioned a watch because that’s what they knew, what they were familiar with. They’d just had a smart watch in the study, but they hadn’t really liked it. It was obtrusive and clunky. When they described what they were wanting it was clear it didn’t need to be a watch, just something highly mobile, wearable and very easy to use.”

The team’s biggest takeaways dispelled their initial assumptions about a technological solution. The ultimate form factor would have to address the participants’ needs for simplicity. No fancy buttons, settings, or the like. It just needed to work. In addition, it had to be highly mobile, maybe a button or pin that could be worn on a lapel, shirt, or blouse. Finally, it had to be unobtrusive and private. None of these were apparent going into the study, and while many of them may have been discoverable without functioning technology, the team’s insights all resulted from real users using real artifacts.

The Case of the Star Trek Holodeck

Renowned ethnographer Steve Portigal and his team were working with a client on a futuristic smart TV. As Steve put it, “To call it a smart TV doesn’t do it justice. It was a smart TV on steroids.” At first blush, the engagement seemed straightforward: help the client through a feature prioritization exercise with consumers. But fairly soon after the team began, it realized its client may not have thought through their assumptions behind the device.

The complexity of the project added its own challenges. The client’s concern about security and confidentiality prevented research team members from really understanding the technology, its features, capabilities, and intended experience before they were to engage with consumers. The client had created two very elaborate prototypes. The first, a high-fidelity simulation, required 12 hours for the client’s team to unpack, install, and set up. “This was like something you’d normally only see at a tradeshow. It reminded me of the holodeck on Star Trek: The Next Generation,” Steve remarked. “We really didn’t know what was ‘real’ and what was scripted.” The second artifact was two full-sized mock-ups of screen displays mounted on foam core.

The research was split into two parts as well. In the first part, consumers would interact with the high-resolution simulation in the client’s facility, with the expectation they would prioritize features. In the second part, a subset of these participants were enrolled to help understand how the device would fit in the context of their homes.

The client’s goals for feature prioritization began to unravel during the engagement with the high-fidelity simulation. Users were confused by the mishmash of features. There was no perceivable narrative for the product, no underlying reason why it could it do all of these things. The users started offering up use cases the client had never thought of. “Oh, this is something that brings people together” or, “Oh, maybe this would be tabletop-like and we’d sit around it, interact digitally and share an experience.”

After having seen and experienced the high-fidelity simulation, these participants were primed to consider the foam-core artifacts with a deeper understanding than simply, “Could it fit in this room?” The lower-fidelity mock-ups provoked rich conversations about the underlying value proposition of the product itself. Rather than focusing on the simpler aspects of how the device might fit in the users’ homes, the team was able to probe into more interesting questions such as, “Now we’ve got this on your wall, let’s talk about you owning one of these and how you’d live with it. What do you expect it to do?” When Steve and the team witnessed the challenges users were having and understood it was due to a lack of narrative, they took the research in a completely different direction. This was a surprise to both the team and the client, but exploring the narratives behind the device opened up a richer understanding of these users’ needs, desires, and points of view. The responses enabled insights the client hadn’t given much thought to or even realized were important to understand.

For example, users would hold up the low-fidelity mockups to their wall and say, “Oh, yeah, I’d walk up to it and do this ….” The client thought they were testing the solution, but the users’ reactions made it clear to the team they were revealing the problem space. Because the screen was in their homes, users began to ponder how it might work with existing screens they already had, and what sorts of engagements it would enable based on its location, say, in the kitchen versus another room. The participants were reflecting back an experience: the bringing of friends and family together. For Steve and the team, that was huge. The client didn’t have that kind of narrative; they had features. In looking for something to grab onto because the device hadn’t been designed with a narrative in mind, users were offering up their own!

As discussed in Chapter 8, it’s generally not a good idea to go high-fidelity, high-investment while in the problem space. Teams that end up here usually do so by accident, such as this team. It thought it knew what the solution was. The client’s users informed it otherwise by asking, “Solution to what?” Still, as Portigal shared with us, the fact the client had produced such high-fidelity artifacts shifted the research in fascinating ways. It may not have been cost-effective, but it was still beneficial: If the client had followed conventional wisdom (starting with low fidelity and moving to higher fidelity only later), users would not have offered up as many insights or such rich understandings of the low-fidelity mockups in their homes. Without having experienced the touchscreen, moving data between devices using gestures, and other Star Trek–like behaviors, these users wouldn’t have suspended their disbelief about the foam-core artifacts.

The client recognized business value in the results of the research team’s effort, but Steve believed the process revealed a more valuable contribution: an opportunity to improve the client’s product development process. The team suggested the client first establish a compelling narrative, test that, and then build features supporting the tested narrative. Without such a narrative, users provided one; when the client offered an ambiguous artifact (high-resolution but without a compelling narrative), the users were compelled to make one up.

This last point underscores the power of PrD: We will work hard to overcome gaps in our understanding of an artifact. The stories these people told illuminated their underlying values, desires, and, ultimately, the business value for the client’s device.

Direct Artifacts

Most of the time, the artifacts we create in PrD sessions are a direct expression of a new product or service offering. The three cases in this section are a sample of the wide range of possibilities: a new form factor for a high-tech test instrument, a bicycle accessory, and a new approach to therapy.

The Case of the New Case

Leo was working for a product group with a serious problem: The entire product category it had originally created and subsequently been building, iterating, and engineering for over 15 years was under attack on numerous fronts. Competitors were shifting the focus away from the company’s core competency, customers were grumbling about the product’s usability, and key engineering advantages based on unique hardware designs were being eroded by ever-improving software. Of several initiatives launched to counteract the erosion, one was a simple refresh of the product packaging, updating it to a more contemporary look and feel. None of the features or functions (other than front panel knobs, ports, and other superficial physical attributes) would be touched.

This initiative was in flight when Leo came onto the scene. The group hoped to get feedback from sales teams about the proposed new look at an upcoming sales conference. The plan was to move some knobs and input ports from the back to the side of the box, and change its envelope dimensions as well as the color of its plastic housing. The engineering team had settled on an incremental shift in the current design. A newcomer (like Leo) looking at the old and new designs would have difficulty distinguishing much of a difference. The product manager explained the proposed changes were a response to several years of complaints about those specific issues. For the upcoming sales meeting, the team had decided to mock up three variations of these elements using foam-core models.

Leo realized that if ever there was an opportunity for PrD, this was it. He gathered together the core team of engineers for an hour, asking them to brainstorm all of the possible ways they could address the customer complaints—without building a box (Figure A.14). As Leo put it, “Once the constraint of incrementalism was removed, amazing things happened. Entire parts of the design were eliminated, functional elements such as the power supply or the disk drive, long considered ‘anchors,’ were reconsidered with completely different form factors. Even the screen, a key hot button for their users, became a target for reconsideration. At the end of a single hour we had generated four substantively different proposals, all of which we knew were problematic (both engineering- and usability-wise) (Figure A.15).”

Figure A.14 The results of a brief Creation Session with key engineers

Figure A.15 The initial sketches of what would become high-res Photoshop images

The team crafted quick Photoshop mockups to use as artifacts. Given the enormous risk of the proposed designs, even creating 3D foam-core mockups of the ideas seemed an unnecessary level of investment. The team had gone in with the assumption that the product’s form factor would remain unchanged. Leo prompted them to call out and question this assumption. What if they did change the form factor? Perhaps more importantly, what if changing the form factor didn’t address the perceived customer pain points? Would a radical change in form factor reveal true customer needs that might not need a changed form factor at all? Photoshopped screens as artifacts were more than adequate to test these notions.

Stakeholder reactions to the more radical proposals revealed important unaddressed needs, such as keeping certain parts together (little bits and pieces evaporate quickly in labs) while at the same time making the solution easily transportable. The team learned about leveraging the compute power already existing at customer sites, whenever possible, while providing the top-notch accuracy afforded by the client’s specially built hardware. In short, through PrD, the team gained a much richer understanding of the client’s customers and of sales teams’ needs, leading to a much broader set of possible offerings. These offerings were made possible only by calling out form factor as an assumption and directly questioning it.

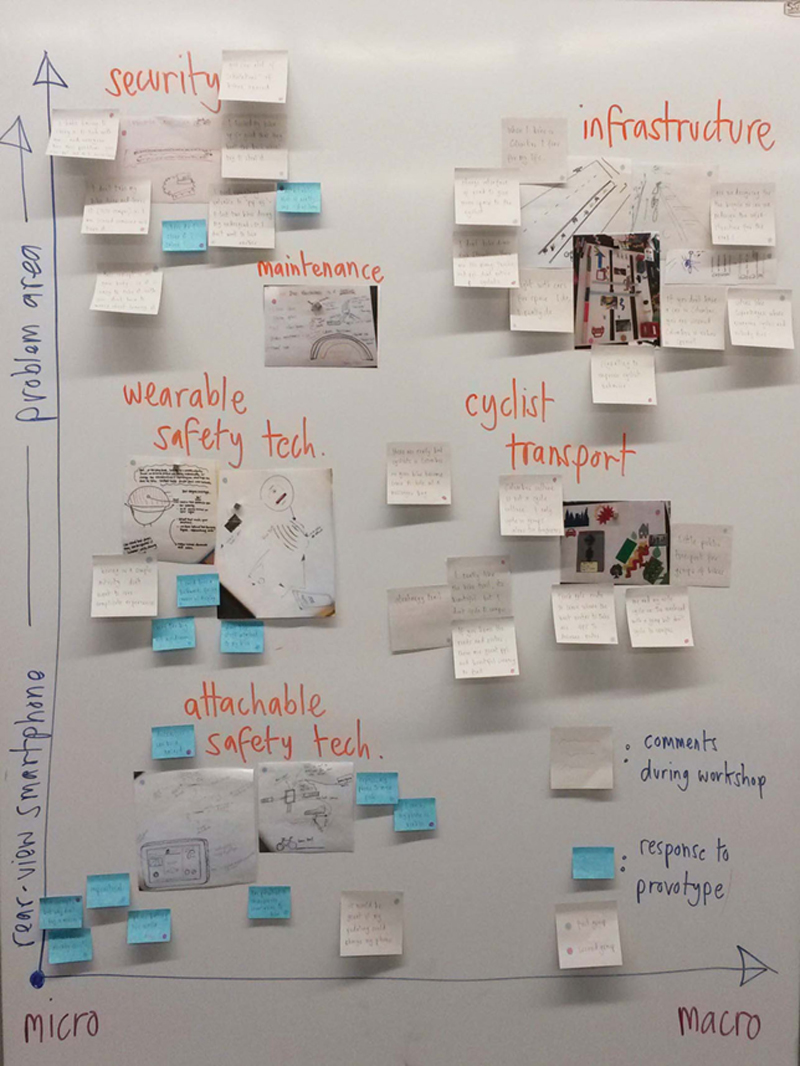

The Case of the Balking Bicyclists

Ohio State University graduate student David McKenzie had been drawn to the work of Liz Sanders, specifically in the area of research through making. As he began exploring the process of PrD he decided to focus on cyclists on campus and where their needs weren’t being met.

True to the principle of Create, Discover, Analyze, David and his team generated concepts based on an initial idea but without much supporting data. He and his team created a bicycle attachment allowing riders to use their smartphone as a rearview mirror (Figure A.16).

Figure A.16 The initial artifact: a 3D printed accessory

Once created, David introduced the design to a group of stakeholders for their reaction. David put it succinctly, “They completely trashed it.” Recognizing the stakeholders might have other ideas for what made more sense, David engaged them in Participatory Design sessions in which they could craft their own artifact using a variety of materials and tools (Figures A.17 and A.18).

Figure A.17 A Participatory Design session with stakeholders in response to the initial artifact

Figure A.18 Participatory Design session generating stakeholder notions of a needed accessory

In spite of the stakeholders’ reaction to the initial concept, David and his team captured excellent information: what cyclists really wanted and the problems they have on or around campus and the Greater Columbus, Ohio, area. Out of several sessions, David created a “stakeholder map,” a whiteboard with sticky notes (Figure A.19).

Figure A.19 Stakeholder map. Sticky notes placed in a two-dimensional graph. X is the scale of the problem and Y is the problem area of abstraction

The results of this initial round revealed two areas completely different from the one assumed by his team at the start: security and infrastructure. Where his team had assumed cyclists would be concerned about lack of bicycle lanes and a desire for improved understanding of their surroundings, the underlying reactions to their artifact suggested a deep concern for security. For example, the more hardcore cyclists completely rejected the idea of using a smartphone as a resource. Although they complained about the clunkiness of the prototype, they also mentioned the risk of having their phone being exposed to theft.

The artifact generated stories about lights and even bikes being stolen on campus. Even their assumption about Columbus’ lack of proper bicycle infrastructure was revealed to be unfounded. The team learned Columbus actually has a good cycling route and most cyclists don’t use roads to move through the city.

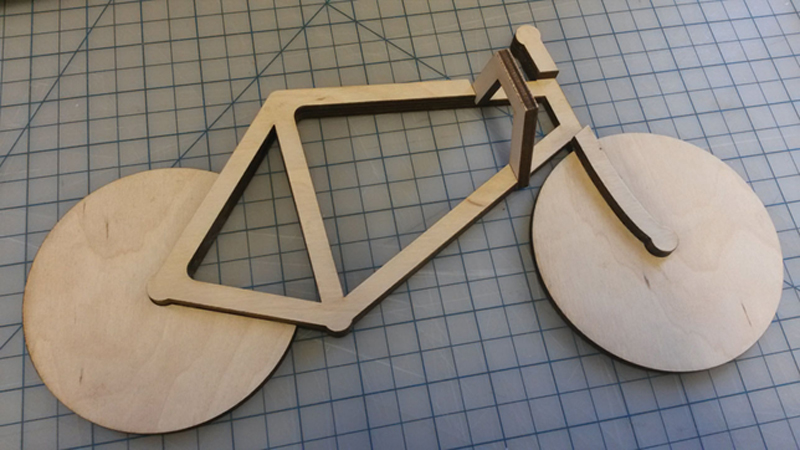

With this new understanding, David and his design team considered a completely different artifact—a locking mechanism integrated into the bike itself (Figure A.20).

Figure A.20 An artifact revealing the need for security built into the bike

In a subsequent set of Engagement Sessions, David validated the need for security: Stakeholders were unconvinced this solution would be enough! As with the prior session, he welcomed the participants to craft their own ideas in response to the second iteration.

David knew, in spite of the ongoing criticism of his ideas, that he was making forward progress. Using a process he calls “Trash and Praise” (in which respondents rate offerings on a scale of 0 to 10, with Trash being 0 and Praise being 10), David had moved from low scores in the first iteration to middling scores in the second.

Shifting gears, so to speak, David’s design team turned to social stigma as a way of reducing theft: Could the bike signal to a prospective thief a sense of shame? In the third round of Engagement Sessions they offered an artifact relying on this principle, to little fanfare. Security remained an important issue, but the group was unconvinced that stigma would be as effective a deterrent to theft as brute force (i.e., a strong lock).

David’s case illustrates another principle of PrD: The Faster We Go, the Sooner We Know. All six sessions—three Creation Sessions and three Engagement Sessions—took only about two weeks of work to complete. In fact, David suggests, “It would have taken half the time if recruiting hadn’t been such a stumbling block.” He goes on, “The artifacts themselves take less than an hour to make. The turnaround of analysis and discussion are done in a single afternoon.”

David has discovered many of the principles of PrD in the short engagement he’s had with it. He told us some of his takeaways include the realization there’s a big difference between sacrificial artifacts and refined prototypes. The creation of crude artifacts is a quick turnaround. In his first attempt, he used 3D printing; by the last he was using cardboard. The artifacts, he told us, create discussion entirely different from the purpose of the artifact. When these objects are in front of people, they project onto them. This led to valuable surprises and discoveries. That the artifact doesn’t actually work, he told us, changes the dynamic with participants, generating a wider range of discussion. Steering the conversation toward the problem space by using the artifact led David to more interesting discussions with stakeholders, less about refining the artifact and more about the underlying problem it’s trying to address.

And finally, David told us, getting going immediately has great value—even if you’re dead wrong. Offering something that will be trashed, as David did in his first iteration, generated a strong reaction and response from stakeholders, revealing their passions around the real problems they faced.

The Case of the Transformed Treatment

Christopher Stapleton, with over 25 years under his belt in developing experiences and environments for companies such as Disney, Universal Studios, and Nickelodeon, had been sitting in on therapy sessions with People with Aphasia (PWAs). It occurred to him the work he’d become an expert in (immersive entertainment) would be a spectacular way to enable these patients and improve their lives.

He had a hunch his years of experience with alternative storytelling techniques could be a useful form of therapy. As Christopher told us, “I’m an entertainment story guy coming into a science world and working in their problem space. I’m a novice in their problem space. But I am an expert in what I do. They need help thinking outside the box. PrD is important because we have different perceptions of problem spaces and different solutions and processes. People with different backgrounds and expertise will see the problem spaces differently. They need to be able to play well together in order to come together and think outside the box.

“PWAs find their therapy emotionally overwhelming. They still have the cognitive abilities of all they’ve learned, their expertise. It’s just that now they can’t communicate it. It’s like they’re prisoners in their own minds. Traditional, evidence-based therapy for PWAs teaches language through drill and practice. Therapists focus on this relearning of language, and it can make therapy excruciating. It reminded me of having to go back to preschool as a 50-some-year old. Well, I thought, what if we question this approach? What if they don’t focus on the language impairment but on something else? What if they focus on storytelling? PWAs have lost their ability to tell stories with words, but they can still imagine stories.”

At Simiosys Real World Labs, Christopher and his research partner, Dr. Janet Whiteside (executive director), began with this assumption and started their work for the University of Central Florida’s Aphasia House. UCF’s Aphasia House follows the Life Participation Approach to Aphasia (LPAA), whose therapists want to improve communication through creatively building relationships. They are very open to trying new things, Christopher told us, which made this effort possible.

They offered clients an artifact they call the “Story Trove.” “It’s sort of like evidence to a detective or a hope chest. It’s a box that tells a story by what’s in it and how it’s layered and how you unpackage it. It makes you jump to conclusions, intentionally. You use these objects to paint with your imagination. You put objects together as a story. Objects divert attention from being focused directly on the client. This depressurizes the situation and facilitates discovery. It pushes and challenges clients without making them want to give up.”

Christopher is referring to the Story Trove as a social object, a key aspect of PrD (Figure A.21).

Figure A.21 Story Troves reveal many stories beyond words through the juxtaposition of artifacts that paint with the audience’s imagination

By introducing the Story Trove, Christopher and his team were able to change the traditional therapist–client dynamic. With the Story Trove, everyone comes to the table: the client, the therapist, and the caregiver (Figure A.22). His operating assumption rested on the question, “Why should the PWAs have to do all the work?” By bringing everyone to the Story Trove, they introduced a notion of a “lifetime of therapy.” The caregiver started to model the therapist and the therapist started to train the caregiver.

Figure A.22 Through “Conversational Storytelling,” group engagement with Therapist, Caregivers and PWAs rediscover the rich exchange of communication while using story to rediscover language skills

One day, due to events outside the team’s control, client schedules got mashed up and two clients showed up for the same appointment. Much in the PrD spirit of improv, Christopher believes in leaving room for mistakes to happen, finding great value in the breakthroughs that can result. Rather than rescheduling one of the clients the team decided to proceed with both, to eye-opening results. Including both PWAs in the same appointment, the team discovered the two clients did much better talking to each other than talking to the others present. This was quite a discovery, suggesting another way to improve therapy with PWAs.

Simiosys Real World Labs has demonstrated a completely new way of thinking about therapy for PWAs, all through artifact building and experimentation. Their discoveries have made Christopher passionate about PrD.

In a recent keynote to the Aphasia Access Leadership Summit, Christopher presented his PrD research on Conversational Storytelling. He told us: “We’re transforming their approach, giving a keynote at their conference and I’m not even a scientist! I’m not an expert! We just saw something and within six months were showing results, transforming the entire industry. We turned it upside down, starting with story, not language.

“We also realized we need to apply PrD in therapy to design the treatment, a new product solution, for each client. There’s innovation in the field, yes, but we need innovation for each particular client. The field is so preoccupied with evidence-based data. When I’m asked ‘Where’s the data to support that?’ now I say, ‘This is PrD. I’m being presumptive. This is the stage before evidence-based data.’ I use the term ‘PrD’ quite a bit now. Its whole basis is working with your hunches. PrD allows one to get very far very fast.”

The Art of Facilitation

Sometimes stakeholders are not keen on the notion of participating in PrD. In such circumstances it’s typically up to the Facilitator to manage the situation. And, often, the best way to move people past their misgivings and hesitancies is to simply get the process moving. Once they experience it, the resistance tends to melt away. We include this case, not to illustrate a particular artifact, but to underscore the need for mastery in running the Engagement Sessions.

The Case of the Reticent Respondent

Leo was on the road with a team doing early concept testing for a completely new product category. The challenge of researching new product categories is that there is only analogous information to go on. The thing is sort of like this and sort of like that, but in fact it is completely new and can’t be described in terms of existing products. The product manager was having a tough time putting a case together because he couldn’t find market data that really applied. So, he gathered a team: a hardware engineer, a software architect, himself, and Leo as the UX guy, and took it on the road.

The protocol was in two stages: The first asked users to tell the team about a recent experience using the related products by walking through a typical use case. The second stage asked them to “design” the new product using a prefixed set of elements that covered all of the related products’ functionality. The hope was that users would naturally design the hybrid product representing the new category. There were several assumptions in this PrD:

• Users needed the new product category.

• Users would put the new product together based on component parts.

• Having users perform a walkthrough first would prime them for the design effort.

The team arrived at a computer components manufacturer, one of the company’s best customers. The meeting had been set up with what the team hoped was a perfect candidate to test its assumptions. After the team took its seats in the conference room, the customer team came in: the team manager along with three of his team members, Mike, Ivan, and Josef.5

After getting the pleasantries out of the way, Leo turned to the manager and asked who on his team was going to help out that morning. He, in turn, turned to his team and asked them. It was clearly the first time any of them had heard Leo and his team were going to be there or what the session was going to be about. Seeing a catastrophe in the making, Leo jumped in and said, “Before you all raise your hands at once, let me explain a little about what we’re hoping to do today.” After hearing a quick description, the research team was heartened to see Mike shrug his shoulders and agree to be the sacrificial lamb. At that point, the research team expected the rest of the customer team to leave, allowing Mike to speak openly and directly.

Sadly, that wasn’t going to be the case. Mike as it turned out was the junior guy on the team; he had the least domain knowledge and obviously had lowest status in the group. Add to that a strong dose of performance anxiety and the research team was beginning to sense the session was going to be nightmare. Because the warm-up exercise was both entertaining and something he could do, Mike loosened up a bit. Not so for Ivan. Ivan sat behind and off to the side of Mike, his arms crossed with his face in a permanent scowl. He gave the research team the warm feelings of a government intelligence handler, uttering single-syllable grunts if he said anything at all.

An hour later and Mike was through his ordeal. The research team knew it wasn’t getting the best information from him, but it was good enough to not stop early. And then Leo turned to Ivan: “So, I noticed you seemed to have some opinions about what Mike was doing. We appreciate that you didn’t interrupt him when he was trying to work with us, but I’m interested in hearing what you have to say.”

Ivan’s eyes narrowed slightly and then his arms unfolded and he sat a little straighter in the chair. “It’s obvious,” he said with a thick accent, only adding to the atmosphere, “vat you are trying to do.” And with a small self-satisfied smile, for the next 30 minutes he laid out the team’s entire strategy. Even more importantly, he endorsed it. “Eff you could make zhat happen, vell, I’ve never zeen anyting like it, and it vould be a uzeful device.” Without the team’s knowledge or prompting, a senior engineer, who would likely be the target candidate for the new concept, not only had understood what the team was doing but also saw great value in it.

So, you never know. Sometimes you just forge ahead and hope for the best, facilitating your way through a bad situation, and if you’re lucky get pleasantly surprising results.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.