C H A P T E R 1

Overview of HTML5

This book is about HTML5 Programming. Before you can understand HTML5 programming, however, you need to take a step back and understand what HTML5 is, a bit of the history behind it, and the differences between HTML 4 and HTML5.

In this chapter, we get right to the practical questions to which everyone wants answers. Why HTML5, and why all the excitement just now? What are the new design principles that make HTML5 truly revolutionary—but also highly accommodating? What are the implications of a plugin-free paradigm; what’s in and what’s out? What’s new in HTML, and how does this kick off a whole new era for web developers? Let’s get to it.

The Story So Far—The History of HTML5

HTML goes back a long way. It was first published as an Internet draft in 1993. The ’90s saw an enormous amount of activity around HTML, with version 2.0, versions 3.2, and 4.0 (in the same year!), and finally, in 1999, version 4.01. In the course of its development, the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) assumed control of the specification.

After the rapid delivery of these four versions though, HTML was widely considered a dead-end; the focus of web standards shifted to XML and XHTML, and HTML was put on the back burner. In the meantime, HTML refused to die, and the majority of content on the web continued to be served as HTML. To enable new web applications and address HTML’s shortcomings, new features and specifications were needed for HTML.

Wanting to take the web platform to a new level, a small group of people started the Web Hypertext Application Working Group (WHATWG) in 2004. They created the HTML5 specification. They also began working on new features specifically geared to web applications—the area they felt was most lacking. It was around this time that the term Web 2.0 was coined. And it really was like a second new web, as static web sites gave way to more dynamic and social sites that required more features—a lot more features.

The W3C became involved with HTML again in 2006 and published the first working draft for HTML5 in 2008, and the XHTML 2 working group stopped in 2009. Another two years passed, and that is where we stand today. Because HTML5 solves very practical problems (as you will see later), browser vendors are feverishly implementing its new features, even though the specification has not been completely locked down. Experimentation by the browsers feeds back into and improves the specification. HTML5 is rapidly evolving to address real and practical improvements to the web platform.

MOMENTS IN HTML

The Myth of 2022 and Why It Doesn’t Matter

The HTML5 specification that we see today has been published as a working draft—it is not yet final. So when does it get cast in stone? Here are the key dates that you need to know. The first is 2012, which is the target date for the candidate recommendation. The second date is 2022, which is the proposed recommendation. Wait! Not so fast! Don’t close this book to set it aside for ten years before you consider what these two dates actually mean.

The first and nearest date is arguably the most important one, because once we reach that stage, HTML5 will be complete. That’s just around the corner. The significance of the proposed recommendation (which we can all agree is a bit distant) is that there will then be two interoperable implementations. In other words, two browsers equipped with completely interoperable implementations of the entire specifications—a lofty goal that actually makes the 2022 deadline seem ambitious. After all, we haven’t even achieved that in HTML4 and only recently for CSS2!

What is important, right now, is that browser vendors are actively adding support for many very cool new features, and some of those are already in the Final Call for comments phase. Depending on your audience, you can start using many of these features today. Sure, any number of minor changes will need to be made down the road, but that’s a small price to pay for enjoying the benefits of living on the cutting edge. Of course, if your audience uses Internet Explorer 6.0, many of the new features won’t work and will require emulation—but that’s still not a good reason to dismiss HTML5. After all, those users, too, will eventually be jumping to a later version. Many of them will probably move to Internet Explorer 9.0 right away, and that version of IE supports many more HTML5 features. In practice, the combination of new browsers and improving emulation techniques means you can use many HTML5 features today or in the very near future.

Who Is Developing HTML5?

We all know that a certain degree of structure is needed, and somebody clearly needs to be in charge of the specification of HTML5. That challenge is the job of three important organizations:

- Web Hypertext Application Technology Working Group (WHATWG): Founded in 2004 by individuals working for browser vendors Apple, Mozilla, Google, and Opera, WHATWG develops HTML and APIs for web application development and provides open collaboration of browser vendors and other interested parties.

- World Wide Web Consortium (W3C): The W3C contains the HTML working group that is currently charged with delivering their HTML5 specification.

- Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF): This task force contains the groups responsible for Internet protocols such as HTTP. HTML5 defines a new WebSocket API that relies on a new WebSocket protocol, which is under development in an IETF working group.

A New Vision

HTML5 is based on various design principles, spelled out in the WHATWG specification, that truly embody a new vision of possibility and practicality.

- Compatibility

- Utility

- Interoperability

- Universal access

Compatibility and Paving the Cow Paths

Don’t worry; HTML5 is not an upsetting kind of revolution. In fact, one of its core principles is to keep everything working smoothly. If HTML5 features are not supported, the behavior must degrade gracefully. In addition, since there is about 20 years of HTML content out there, supporting all that existing content is important.

A lot of effort has been put into researching common behavior. For example, Google analyzed millions of pages to discover the common ID and Class names for DIV tags and found a huge amount of repetition. For example, many people used DIV id="header" to mark up header content. HTML5 is all about solving real problems, right? So why not simply create a <header> element?

Although some features of the HTML5 standard are quite revolutionary, the name of the game is evolution not revolution. After all, why reinvent the wheel? (Or, if you must, then at least make a better one!)

Utility and the Priority of Constituencies

The HTML5 specification is written based upon a definite Priority of Constituencies. And as priorities go, “the user is king.” This means, when in doubt, the specification values users over authors, over implementers (browsers), over specifiers (W3C/WHATWG), and over theoretical purity. As a result, HTML5 is overwhelmingly practical, though in some cases, less than perfect.

Consider this example. The following code snippets are all equally valid in HTML5:

id="prohtml5"

id=prohtml5

ID="prohtml5"

Sure, some will object to this relaxed syntax, but the bottom line is that the end user doesn’t really care. We’re not suggesting that you start writing sloppy code, but ultimately, it’s the end user who suffers when any of the preceding examples generates errors and doesn’t render the rest of the page.

HTML5 has also spawned the creation of XHTML5 to enable XML tool chains to generate valid HTML5 code. The serializations of the HTML or the XHTML version should produce the same DOM trees with minimal differences. Obviously, the XHTML syntax is a lot stricter, and the code in the last two examples would not be valid.

Secure by Design

A lot of emphasis has been given to making HTML5 secure right out of the starting gate. Each part of the specification has sections on security considerations, and security has been considered up front. HTML5 introduces a new origin-based security model that is not only easy to use but is also used consistently by different APIs. This security model allows us to do things in ways that used to be impossible. For example, it allows us to communicate securely across domains without having to revert to all kinds of clever, creative, but ultimately Non-secure hacks. In that respect, we definitely will not be looking back to the good old days.

Separation of Presentation and Content

HTML5 takes a giant step toward the clean separation of presentation and content. HTML5 strives to create this separation wherever possible, and it does so using CSS. In fact, most of the presentational features of earlier versions of HTML are no longer supported, but will still work, thanks to the compatibility design principle mentioned earlier. This idea is not entirely new, though; it was already in the works in HTML4 Transitional and XHTML1.1. Web designers have been using this as a best practice for a long time, but now, it is even more important to cleanly separate the two. The problems with presentational markup are:

- Poor accessibility

- Unnecessary complexity (it’s harder to read your code with all the inline styling)

- Larger document size (due to repetition of style content), which translates into slower-loading pages

Interoperability Simplification

HTML5 is all about simplification and avoiding needless complexity. The HTML5 mantra? “Simple is better. Simplify wherever possible.” Here are some examples of this:

- Native browser ability instead of complex JavaScript code

- A new, simplified

DOCTYPE - A new, simplified character set declaration

- Powerful yet simple HTML5 APIs

We’ll say more about some of these later.

To achieve all this simplicity, the specification has become much bigger, because it needs to be much more precise—far more precise, in fact, than any previous version of the HTML specification. It specifies a legion of well-defined behaviors in an effort to achieve true browser interoperability by 2022. Vagueness simply will not make that happen.

The HTML5 specification is also more detailed than previous ones to prevent misinterpretation. It aims to define things thoroughly, especially web applications. Small wonder, then, that the specification is over 900 pages long!

HTML5 is also designed to handle errors well, with a variety of improved and ambitious error-handling plans. Quite practically, it prefers graceful error recovery to hard failure, again giving A-1 top priority to the interest of the end user. For example, errors in documents will not result in catastrophic failures in which pages do not display. Instead, error recovery is precisely defined so browsers can display “broken” markup in a standard way.

Universal Access

This principle is divided into three concepts:

- Accessibility: To support users with disabilities, HTML5 works closely with a related standard called Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) Accessible Rich Internet Applications (ARIA). WAI-ARIA roles, which are supported by screen readers, can be already be added to your HTML elements.

- Media Independence: HTML5 functionality should work across all different devices and platforms if at all possible.

- Support for all world languages: For example, the new

<ruby>element supports the Ruby annotations that are used in East Asian typography.

A Plugin–Free Paradigm

HTML5 provides native support for many features that used to be possible only with plugins or complex hacks (a native drawing API, native video, native sockets, and so on).

Plugins, of course, present many problems:

- Plugins cannot always be installed.

- Plugins can be disabled or blocked (for example, the Apple iPad does not ship with a Flash plugin).

- Plugins are a separate attack vector.

- Plugins are difficult to integrate with the rest of an HTML document (because of plugin boundaries, clipping, and transparency issues).

Although some plugins have high install rates (Adobe Flash, for example), they are often blocked in controlled corporate environments. In addition, some users choose to disable these plugins due to the unwelcome advertising displays that they empower. However, if users disable your plugin, they also disable the very program you’re relying on to display your content.

Plugins also often have difficulty integrating their displays with the rest of the browser content, which causes clipping or transparency issues with certain site designs. Because plugins use a self-contained rendering model that is different from that of the base web page, developers face difficulties if pop-up menus or other visual elements need to cross the plugin boundaries on a page. This is where HTML5 comes on the scene, smiles, and waves its magic wand of native functionality. You can style elements with CSS and script with JavaScript. In fact, this is where HTML5 flexes its biggest muscle, showing us a power that just didn’t exist in previous versions of HTML. It’s not just that the new elements provide new functionality. It’s also the added native interaction with scripting and styling that enables us to do much more than we could ever do before.

Take the new canvas element, for example. It enables us to do some pretty fundamental things that were not possible before (try drawing a diagonal line in a web page in HTML 4). However, what’s most interesting is the power that we can unlock with the APIs and the styling we can apply with just a few lines of CSS code. Like well-behaved children, the HTML5 elements also play nicely together. For example, you can grab a frame from a video element and display it on a canvas, and the user can just click the canvas to play back the video from the frame you just showed. This is just one example of what a native code has to offer over a plugin. In fact, virtually everything becomes easier when you’re not working with a black box. What this all adds up to is a truly powerful new medium, which is why we decided to write a book about HTML5 programming, and not just about the new elements!

What’s In and What’s Out?

So, what really is part of HTML5? If you read the specification carefully, you might not find all of the features we describe in this book. For example, you will not find Geolocation and Web Workers in there. So are we just making this stuff up? Is it all hype? No, not at all!

Many pieces of the HTML5 effort were originally part of the HTML5 specification and were then moved to separate standards documents to keep the specification focused. It was considered smarter to discuss and edit some of these features on a separate track before making them into official specifications. This way, one small contentious markup issue wouldn’t hold up the show of the entire specification.

Experts in specific areas can come together on mailing lists to discuss a given feature without the crossfire of too much chatter. The industry still refers to the original set of features, including Geolocation, and so on as HTML5. Think of HTML5, then, as an umbrella term that covers the core markup, as well as many cool new APIs. At the time of this writing, these features are part of HTML5:

- Canvas (2D and 3D)

- Cross-document messaging

- Geolocation

- Audio and Video

- Forms

- MathML

- Microdata

- Server-Sent events

- Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG)

- WebSocket API and protocol

- Web origin concept

- Web storage

- Indexed database

- Application Cache (Offline Web Apps)

- Web Workers

- Drag and Drop

- XMLHttpRequest Level 2

As you can see, a lot of the APIs we cover in this book are on this list. How did we choose which APIs to cover? We chose to cover features that were at least somewhat baked. Translation? They’re available in some form in more than one browser. Other (less-baked) features may only work in one special beta version of a browser, while others are still just ideas at this point.

As far as browser support goes, there are some excellent online resources that you can use to check current (and future) browser support. The site www.caniuse.com provides an exhaustive list of features and browser support broken down by browser version and the site www.html5test.comchecks the support for HTML5 features in the browser you use to access it.

Furthermore, this book does not focus on providing you with the emulation workarounds to make your HTML5 applications run seamlessly on antique browsers. Instead, we will focus primarily on the specification of HTML5 and how to use it. That said, for each of the APIs we do provide some example code that you can use to detect its availability. Rather than using user agent detection, which is often unreliable, we use feature detection. For that, you can also use Modernizr—a JavaScript library that provides very advanced HTML5 and CSS3 feature detection. We highly recommend you use Modernizr in your applications, because it is hands-down the best tool for this.

MORE MOMENTS IN HTML

What’s New in HTML5?

Before we start programming HTML5, let’s take a quick look at what’s new in HTML5.

New DOCTYPE and Character Set

First of all, the DOCTYPE for web pages has been greatly simplified. Compare, for example, the following HTML4 DOCTYPEs:

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01 Transitional//EN"

"http://www.w3.org/TR/html4/loose.dtd">

Who could ever remember any of these? We certainly couldn’t. We would always just copy and paste some lengthy DOCTYPE into the page, always with a worry in the back of our minds, “Are you absolutely sure you pasted the right one?” HTML5 neatly solves this problem as follows:

<!DOCTYPE html>

Now that’s a DOCTYPE you might just remember. Like the new DOCTYPE, the character set declaration has also been abbreviated. It used to be

<meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8">

Now, it is:

<meta charset="utf-8">

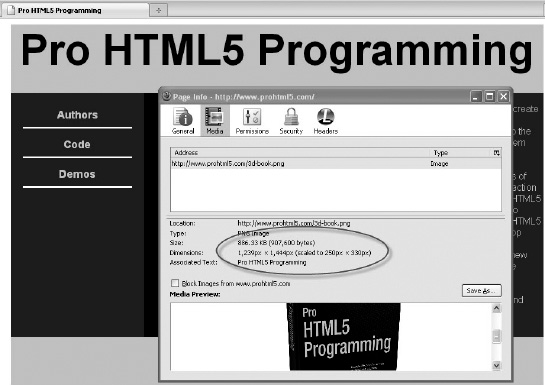

You can even leave off the quotation marks around “utf-8” if you want to. Using the new DOCTYPE triggers the browser to display pages in standards mode. For example, Figure 1-1 shows the information you will see if you open an HTML5 page in Firefox, and you click Tools ![]() Page Info. In this example, the page is rendered in standards mode.

Page Info. In this example, the page is rendered in standards mode.

Figure 1-1. A page rendered in standards-compliant mode

When you use the new HTML5 DOCTYPE, it triggers browsers to render the page in standards-compliant mode. As you may know, Web pages can have different rendering modes, such as Quirks, Almost Standards, and Standards (or no-quirks) mode. The DOCTYPE indicates to the browser which mode to use and what rules are used to validate your pages. In Quirks mode, browsers try to avoid breaking pages and render them even if they are not entirely valid. HTML5 introduces new elements and has marked others as obsolete (more on this in the next section). If you use these obsolete elements, your page will not be valid. However, browsers will continue to render them as they used to.

New and Deprecated Elements

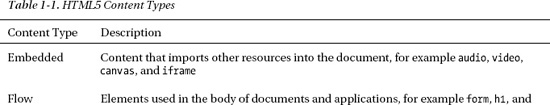

HTML5 introduces many new markup elements, which it groups into seven different content types. These are shown below in Table 1-1.

Most of these elements can be styled with CSS. In addition, some of them, such as canvas, audio, and video, can be used by themselves, though they are accompanied by APIs that allow for fine-grained native programmatic control. These APIs will be discussed in much more detail later in this book.

It is beyond the scope of this book to discuss all these new elements, but most of the sectioning elements (discussed in the next section) are new. The canvas, audio, and video elements are also new in HTML5.

Likewise, we’re not going to provide an exhaustive list of all the deprecated tags (there are many good online resources online for this), but many of the elements that performed inline styling have been marked as obsolete in favor of using CSS, such as big, center, font, and basefont.

Semantic Markup

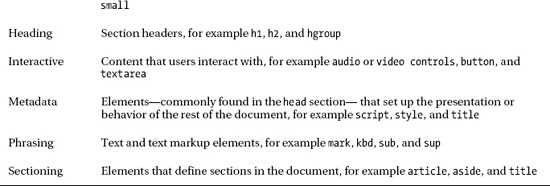

One content type that contains many new HTML5 elements is the sectioning content type. HTML5 defines a new semantic markup to describe an element’s content. Using semantic markup doesn’t provide any immediate benefits to the end user, but it does simplify the design of your HTML pages. What’s more, it will make your pages more machine-readable and accessible. For example, search and syndication engines will definitely be taking advantage of these elements as they crawl and index pages.

As we said before, HTML5 is all about paving the cow paths. Google and Opera analyzed millions of pages to discover the common ID names for DIV tags and found a huge amount of repetition. For example, since many people used DIV id="footer" to mark up footer content, HTML5 provides a set of new sectioning elements that you can use in modern browsers right now. Table 1-2 shows the different semantic markup elements.

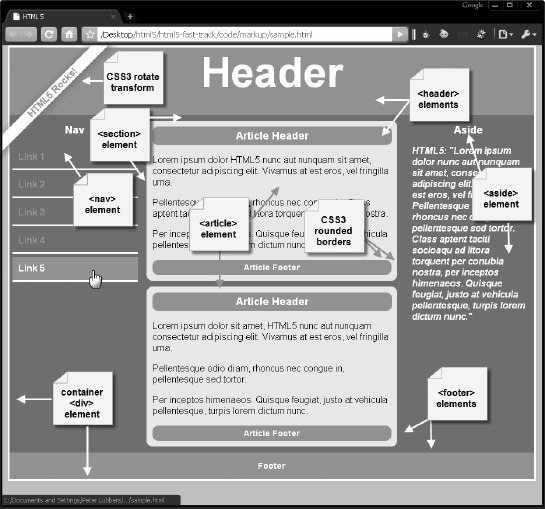

All of these elements can be styled with CSS. In fact, as we described in the utility design principle earlier, HTML5 pushes the separation of content and presentation, so you have to style your page using CSS styles in HTML5. Listing 1-1 shows what an HTML5 page might look like. It uses the new DOCTYPE, character set, and semantic markup elements—in short, the new sectioning content. The code file (sample.html) is available in the code/intro folder.

Listing 1-1. An Example HTML5 Page

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8" >

<title>HTML5</title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="html5.css">

</head>

<body>

<header>

<h1>Header</h1>

<h2>Subtitle</h2>

<h4>HTML5 Rocks!</h4>

</header>

<div id="container">

<nav>

<h3>Nav</h3>

<a href="http://www.example.com">Link 1</a>

<a href="http://www.example.com">Link 2</a>

<a href="http://www.example.com">Link 3</a>

</nav>

<section>

<article>

<header>

<h1>Article Header</h1>

</header>

<p>Lorem ipsum dolor HTML5 nunc aut nunquam sit amet, consectetur adipiscing

elit. Vivamus at

est eros, vel fringilla urna.</p>

<p>Per inceptos himenaeos. Quisque feugiat, justo at vehicula pellentesque,

turpis

lorem dictum nunc.</p>

<footer>

<h2>Article Footer</h2>

</footer>

</article>

<article>

<header>

<h1>Article Header</h1>

</header>

<p>HTML5: "Lorem ipsum dolor nunc aut nunquam sit amet, consectetur

adipiscing elit. Vivamus at est eros, vel fringilla urna. Pellentesque

odio</p>

<footer>

<h2>Article Footer</h2>

</footer>

</article>

</section>

<aside>

<h3>Aside</h3>

<p>HTML5: "Lorem ipsum dolor nunc aut nunquam sit amet, consectetur adipiscing

elit. Vivamus at est eros, vel fringilla urna. Pellentesque odio rhoncus</p>

</aside>

<footer>

<h2>Footer</h2>

</footer>

</div>

</body>

</html>

Without styles, the page would be pretty dull to look at. Listing 1-2 shows some of the CSS code that can be used to style the content. The code file (html5.css) is available in the code/intro folder. This style sheet uses some of the new CSS3 features, such as rounded corners (border-radius) and rotate transformations (transform: rotate();). CSS3—just like HTML5 itself—is still under development, and it is modularized with subspecifications for easier browser uptake (for example, transformation, animation, and transition are all areas that are in separate subspecifications).

Experimental CSS3 features are prefixed with vendor strings to avoid namespace conflicts should the specifications change. To display rounded corners, gradients, shadows, and transformations, it is currently necessary to use prefixes such as -moz- (for Mozilla), o- (for Opera), -webkit- (for WebKit-based browsers such as Safari and Chrome), and -ms- (for Internet Explorer) in your declarations.

Listing 1-2. CSS File for the HTML5 Page

body {

background-color:#CCCCCC;

font-family:Geneva,Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;

margin: 0px auto;

max-width:900px;

border:solid;

border-color:#FFFFFF;

}

header {

background-color: #F47D31;

display:block;

color:#FFFFFF;

text-align:center;

}

header h2 {

margin: 0px;

}

h1 {

font-size: 72px;

margin: 0px;

}

h2 {

font-size: 24px;

margin: 0px;

text-align:center;

color: #F47D31;

}

h3 {

font-size: 18px;

margin: 0px;

text-align:center;

color: #F47D31;

}

h4 {

color: #F47D31;

background-color: #fff;

-webkit-box-shadow: 2px 2px 20px #888;

-webkit-transform: rotate(-45deg);

-moz-box-shadow: 2px 2px 20px #888;

-moz-transform: rotate(-45deg);

position: absolute;

padding: 0px 150px;

top: 50px;

left: -120px;

text-align:center;

}

nav {

display:block;

width:25%;

float:left;

}

nav a:link, nav a:visited {

display: block;

border-bottom: 3px solid #fff;

padding: 10px;

text-decoration: none;

font-weight: bold;

margin: 5px;

}

nav a:hover {

color: white;

background-color: #F47D31;

}

nav h3 {

margin: 15px;

color: white;

}

#container {

background-color: #888;

}

section {

display:block;

width:50%;

float:left;

}

article {

background-color: #eee;

display:block;

margin: 10px;

padding: 10px;

-webkit-border-radius: 10px;

-moz-border-radius: 10px;

border-radius: 10px;

-webkit-box-shadow: 2px 2px 20px #888;

-webkit-transform: rotate(-10deg);

-moz-box-shadow: 2px 2px 20px #888;

-moz-transform: rotate(-10deg);

}

article header {

-webkit-border-radius: 10px;

-moz-border-radius: 10px;

border-radius: 10px;

padding: 5px;

}

article footer {

-webkit-border-radius: 10px;

-moz-border-radius: 10px;

border-radius: 10px;

padding: 5px;

}

article h1 {

font-size: 18px;

}

aside {

display:block;

width:25%;

float:left;

}

aside h3 {

margin: 15px;

color: white;

}

aside p {

margin: 15px;

color: white;

font-weight: bold;

font-style: italic;

}

footer {

clear: both;

display: block;

background-color: #F47D31;

color:#FFFFFF;

text-align:center;

padding: 15px;

}

footer h2 {

font-size: 14px;

color: white;

}

/* links */

a {

color: #F47D31;

}

a:hover {

text-decoration: underline;

}

Figure 1-2 shows an example of the page in Listing 1-1, styled with CSS (and some CSS3) styles. Keep in mind, however, that there is no such thing as a typical HTML5 page. Anything goes, really, and this example uses many of the new tags mainly for purposes of demonstration.

Figure 1-2. An HTML5 page with all the new semantic markup elements

One last thing to keep in mind is that browsers may seem to render things as if they actually understand these new elements. The truth is, however, that these elements could have been renamed foo and bar and then styled, and they would have been rendered the same way (but of course, they would not have any benefits in search engine optimization). The one exception to this is Internet Explorer, which requires that elements be part of the DOM. So, if you want to see these elements in IE, you must programmatically insert them into the DOM and display them as block elements. A handy script that does that for you is html5shiv (http://code.google.com/p/html5shiv/).

Simplifying Selection Using the Selectors API

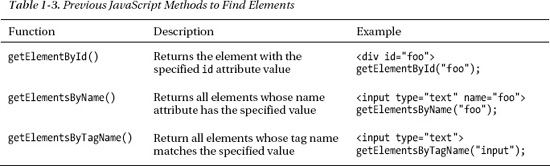

Along with the new semantic elements, HTML5 also introduces new simple ways to find elements in your page DOM. Table 1-3 shows the previous versions of the document object allowed developers to make a few calls to find specific elements in the page.

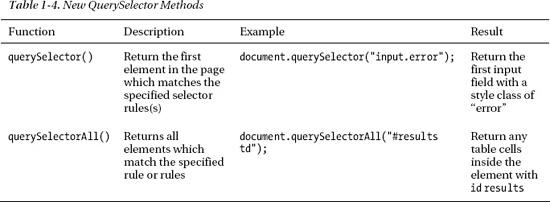

With the new Selectors API, there are now more precise ways to specify which elements you would like to retrieve without resorting to looping and iterating through a document using standard DOM. The Selectors API exposes the same selector rules present in CSS as a means to find one or more elements in the page. For example, CSS already has handy rules for selecting elements based on their nesting, sibling, and child patterns. The most recent versions of CSS add support for more pseudo-classes—for example, whether an object is enabled, disabled, or checked—and just about any combination of properties and hierarchy you could imagine. To select elements in your DOM using CSS rules, simply utilize one of the functions shown in Table 1-4.

It is also possible to send more than one selector rule to the Selector API functions, for example:

// select the first element in the document with the

// style class highClass or the style class lowClass

var x = document.querySelector(“.highClass”, “.lowClass”);

In the case of querySelector(), the first element that matches either rule is selected. In the case of querySelectorAll(), any element matching any of the listed rules is returned. Multiple rules are comma-separated.

The new Selector API makes it easy to select sections of the document that were painful to track before. Assume, for example, that you wanted the ability to find whichever cell of a table currently had the mouse hovering over it. Listing 1-3 shows how this is trivially easy with a selector. The example files for this (querySelector.html and querySelectorAll.html) are located in the code/intro directory.

Listing 1-3. Using the Selector API

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8" />

<title>Query Selector Demo</title>

<style type="text/css">

td {

border-style: solid;

border-width: 1px;

font-size: 300%;

}

td:hover {

background-color: cyan;

}

#hoverResult {

color: green;

font-size: 200%;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<section>

<!-- create a table with a 3 by 3 cell display -->

<table>

<tr>

<td>A1</td> <td>A2</td> <td>A3</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>B1</td> <td>B2</td> <td>B3</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>C1</td> <td>C2</td> <td>C3</td>

</tr>

</table>

<div>Focus the button, hover over the table cells, and hit Enter to identify them

using querySelector('td:hover').</div>

<button type="button" id="findHover" autofocus>Find 'td:hover' target</button>

<div id="hoverResult"></div>

<script type="text/javascript">

document.getElementById("findHover").onclick = function() {

// find the table cell currently hovered in the page

var hovered = document.querySelector("td:hover");

if (hovered)

document.getElementById("hoverResult").innerHTML = hovered.innerHTML;

}

</script>

</section>

</body>

</html>

As you can see from this example, finding the element a user is hovering over is a one-line exercise using:

var hovered = document.querySelector("td:hover");

![]() Note Not only are the Selector APIs handy, but they are often faster than traversing the DOM using the legacy child retrieval APIs. Browsers are highly optimized for selector matching in order to implement fast style sheets.

Note Not only are the Selector APIs handy, but they are often faster than traversing the DOM using the legacy child retrieval APIs. Browsers are highly optimized for selector matching in order to implement fast style sheets.

It should not be too surprising to find that the formal specification of selectors is separated from the specification for CSS at the W3C. As you’ve seen here, selectors are generally useful outside of styling. The full details of the new selectors are outside the scope of this book, but if you are a developer seeking the optimal ways to manipulate your DOM, you are encouraged to use the new Selectors API to rapidly navigate your application structure.

JavaScript Logging and Debugging

Though they’re not technically a feature of HTML5, JavaScript logging and in-browser debugging tools have been improved greatly over the past few years. The first great tool for analyzing web pages and the code running in them was the Firefox add-on, Firebug.

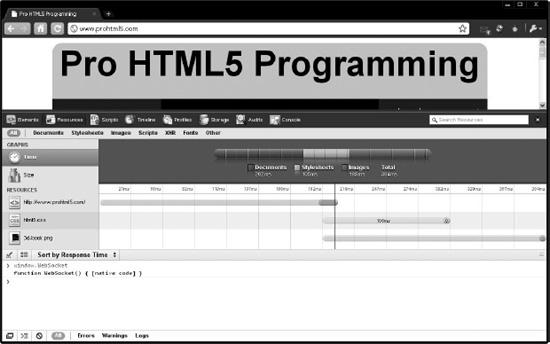

Similar functionality can now be found in all the other browsers’ built-in development tools: Safari’s Web Inspector, Google’s Chrome Developer Tools, Internet Explorer’s Developer Tools, and Opera’s Dragonfly. Figure 1-3 shows the Google Chrome Developer Tools (use the shortcut key CTRL + Shift + J on Windows or Command + Option + J on Mac to access this) that provide a wealth of information about your web pages; these include a debugging console, an elements View, a resource view, and a script view, to name just a few.

Figure 1-3. Developer Tools view in Chrome

Many of the debugging tools offer a way to set breakpoints to halt code execution and analyze the state of the program and the current state of the variables. The console.log API has become the de facto logging standard for JavaScript developers. Many browsers offer a split-pane view that allows you to see messages logged to the console. Using console.log is much better than making a call to alert(), since it does not halt program execution.

window.JSON

JSON is a relatively new and increasingly popular way to represent data. It is a subset of JavaScript syntax that represents data as object literals. Due to its simplicity and natural fit in JavaScript programming, JSON has become the de facto standard for data interchange in HTML5 applications. The canonical API for JSON has two functions, parse() and stringify() (meaning serialize or convert to string).

To use JSON in older browsers, you need a JavaScript library (several can be found at http://json.org). Parsing and serializing in JavaScript are not always as fast as you would like, so to speed up things, newer browsers now have a native implementation of JSON that can be called from JavaScript. The native JSON object is specified as part of the ECMAScript 5 standard covering the next generation of the JavaScript language. It is one of the first parts of ECMAScript 5 to be widely implemented. Every modern browser now has window.JSON, and you can expect to see quite a lot of JSON used in HTML5 applications.

DOM Level 3

One of the most maligned parts of web application development has been event handling. While most browsers support standard APIs for events and elements, Internet Explorer differs. Early on, Internet Explorer implemented an event model that differed from the eventual standard. Internet Explorer 9 (IE9) now supports DOM Level 2 and 3 features, so you can finally use the same code for DOM manipulation and event handling in all HTML5 browsers. This includes the ever-important addEventListener() and dispatchEvent() methods.

Monkeys, Squirrelfish, and Other Speedy Oddities

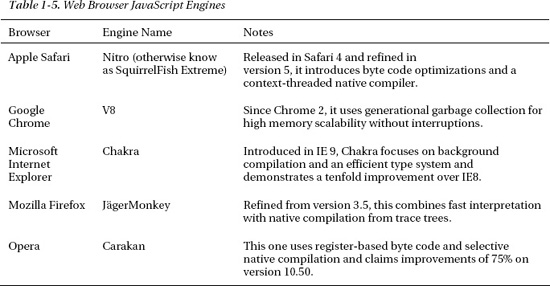

The latest round of browser innovations isn’t just about new tags and new APIs. One of the most significant recent changes is the rapid evolution of JavaScript/ECMAScript engines in the leading browsers. Just as new APIs open up capabilities that were impossible in last-generation browsers, speedups in the execution of the overall scripting engine benefit both existing web applications and those using the latest HTML5 features. Think your browser can’t handle complex image or data processing, or the editing of lengthy manuscripts? Think again.

For the last few years, browser vendors have been in a virtual arms race to see who could develop the fastest JavaScript engine. While the earliest iterations of JavaScript were purely interpreted, the newest engines compile script code directly to native machine code, offering speedups of orders of magnitude compared to the browsers of the mid-2000s.

The action pretty much began when Adobe donated its just-in-time (JIT) compilation engine and virtual machine for ECMAScript—code named Tamarin—to the Mozilla project in 2006. Although only pieces of the Tamarin technology remain in the latest versions of Mozilla, the donation of Tamarin helped spawn new scripting engines in each of the browsers, with names that are just as intriguing as the performance they claim.

All in all, this healthy competition among browser vendors is bringing the performance of JavaScript ever closer to that of native desktop application code.

STILL MORE MOMENTS IN HTML

Summary

In this chapter, we have given you a general overview of the essentials of HTML5.

We charted the history of its development and some of the important dates coming up. We also outlined the four new design principles behind the HTML5 era that is now dawning: compatibility, utility, interoperability, and universal access. Each one of these principles opens the door to a world of possibilities and closes the door on a host of practices and conventions that are now rendered obsolete. We then introduced HTML5’s startling new plugin-free paradigm, and we reviewed what’s new in HTML5, such as a new DOCTYPE and character set, lots of new markup elements, and we discussed the race for JavaScript supremacy.

In the next chapter, we’ll begin by exploring the programming side of HTML5, starting with the Canvas API.