C H A P T E R 13

The Future of HTML5

As you have already seen in this book, HTML5 provides powerful programming features. We also discussed the history behind HTML5's development and HTML5's new plugin-free paradigm. In this chapter, we will look at where things are going. We will discuss some of the features that are not fully baked yet but hold tremendous promise.

Browser Support for HTML5

Adoption of HTML5 features is accelerating with each new browser update. Several of the features we covered have actually shipped in browsers while we wrote this book. HTML5 development in browsers is undeniably gaining tremendous momentum.

Today, many developers still struggle to develop consistent web applications that work with older browsers. Internet Explorer 6 represents the harshest of the legacy browsers in common use on the Internet today But even IE6 has a limited lifetime, as it becomes harder and harder to procure any operating system that supports it. In time, there will be close to zero users browsing the Web with IE6. More and more users of Internet Explorer are being upgraded to the latest versions. There will always be an oldest browser to contend with, but that bar rises as time passes; at the time of this writing, the market share of Internet Explorer 6 is under 10% and falling. Most users who upgrade go straight to a modern replacement. In time, the lowest common denominator will include HTML5 Video, Canvas, WebSocket, and whatever other features you may have to emulate today to reach a wider audience.

In this book, we covered features that are largely stable and shipping in multiple browsers. There are additional extensions to HTML and APIs currently in earlier stages of development. In this chapter, we will look at some of the upcoming features. Some are in early experimental stages, while others may see eventual standardization and wide availability with only minor changes from their current state.

HTML Evolves

In this section, we'll explore several exciting features that may appear in browsers in the near future. You probably won't need to wait until 2022 for these, either. There will probably not be a formalized HTML6; the WHATWG has hinted that future development will simply be referred to as “HTML.” Development will be incremental, with specific features and their specifications evolving individually, rather than as a consolidated effort. Browsers will take up features as they gain consensus, and the upcoming features might even be widely available in browsers well before HTML5 is set in stone. The community responsible for driving the Web forward is committed to evolving the platform to meet the needs of users and developers.

WebGL

WebGL is an API for 3D graphics on the Web. Historically, several browser vendors including Mozilla, Opera, and Google have worked on separate experimental 3D APIs for JavaScript. Today, WebGL is progressing along a path toward standardization and wide availability across HTML5 browsers. The standardization process is taking place with browser vendors and The Khronos Group, the body responsible for OpenGL, a cross-platform 3D drawing standard created in 1992. OpenGL, currently at specification version 4.0, is widely used in gaming and computer-aided design applications as a counterpart and competitor to Microsoft's Direct3D.

As you saw in Chapter 2, you get a 2D drawing context from a canvas element by calling getContext("2d") on the element. Unsurprisingly, this leaves the door open for additional types of drawing contexts. WebGL also uses the canvas element, but through a 3D context. Current implementations use experimental vendor prefixes (moz-webgl, webkit-3d, etc.) as the arguments to the getContext() call. In a WebGL-enabled build of Firefox, for example, you can get a 3D context by calling getContext("moz-webgl") on a canvas element. The API of the object returned by such a call to getContext() is different from the 2D canvas equivalent, as this one provides OpenGL bindings instead of drawing operations. Rather than making calls to draw lines and fill shapes, the WebGL version of the canvas context manages textures and vertex buffers.

HTML in Three Dimensions

WebGL, like the rest of HTML5, will be an integral part of the web platform. Because WebGL renders to a canvas element, it is part of the document. You can position and transform 3D canvas elements, just as you can place images or 2D canvases on a page. In fact, you can do anything you can do with any other canvas element, including overlaying text and video and performing animations. Combining other document elements and a 3D canvas will make heads-up displays (HUDs) and mixed 2D and 3D interfaces much simpler to develop when compared to pure 3D display technologies. Imagine taking a 3D scene and using HTML markup to overlay a simple web user interface on it. Quite unlike the nonnative menus and controls found in many OpenGL applications, WebGL software will incorporate nicely styled HTML5 form elements with ease.

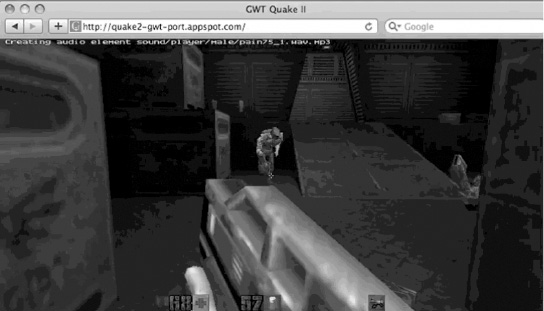

The existing network architecture of the Web will also complement WebGL. WebGL applications will be able to fetch resources such as textures and models from URLs. Multiplayer games can communicate with WebSocket. For example, Figure 13-1 shows an example of this in action. Google recently ported the classic 3D game Quake II to the Web using HTML5 WebSocket, Audio, and WebGL, complete with multiplayer competition. Game logic and graphics were implemented in JavaScript, making calls to a WebGL canvas for rendering. Communication to the server to coordinate player movement was achieved using a persistent WebSocket connection.

3D Shaders

WebGL is a binding for OpenGL ES 2 in JavaScript, so it uses the programmable graphics pipeline that is standardized in OpenGL, including shaders. Shaders allow highly flexible rendering effects to be applied to a 3D scene, increasing the realism of the display. WebGL shaders are written in GL Shading Language (GLSL). This adds yet another single-purpose language to the web stack. An HTML5 application with WebGL consists of HTML for structure, CSS for style, JavaScript for logic, and GLSL for shaders. Developers can transfer their knowledge of OpenGL shaders to a similar API in a web environment.

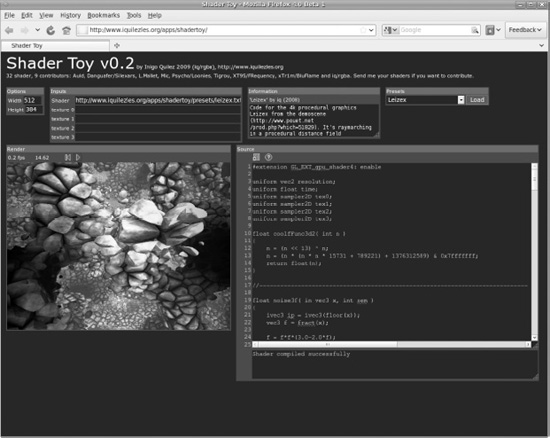

WebGL is likely to be a foundational layer for 3D graphics on the Web. Just as JavaScript libraries have abstracted over DOM and provided powerful high-level constructs, there are libraries providing additional functionality on top of WebGL. Libraries are currently under development for scene graphs, 3D file formats such as COLLADA, and complete engines for game development. Figure 13-2 shows Shader Toy—a WebGL shader workbench built by Inigo Quilez that comes with shaders by nine other demoscene artists. This particular screenshot shows Leizex by Rgba. We can expect an explosion of high-level rendering libraries that bring 3D scene creation power to novice Web programmers in the near future.

Figure 13-2. Shader Toy is a WebGL shader workbench

Devices

Web applications will need access to multimedia hardware such as webcams, microphones, or attached storage devices. For this, there is already a proposed device element to give web applications access to data streams from attached hardware. Of course, there are serious privacy implications, so not every script will be able to use your webcam at will. We will probably see a UI pattern of prompting for user permission as seen in the Geolocation and Storage APIs when an application requests elevated privileges. The obvious application for webcams is video conferencing, but there are many other amazing possibilities for computer vision in web applications including augmented reality and head tracking.

Audio Data API

Programmable audio APIs will do for <audio> what <canvas> did for <img>. Prior to the canvas tag, images on the Web were largely opaque to scripts. Image creation and manipulation had to occur on the sidelines—namely, on the server. Now, there are tools for creating and manipulating visual media based on the canvas element. Similarly, audio data APIs will enable music creation in HTML5 applications. This will help round out the content-creation capabilities available to web applications and move us closer to a self-hosting world of tools to create media on and for the Web. Imagine editing audio on the Web without having to leave the browser.

Simple playback of sounds can be done with the <audio> element. However, any application that manipulates, analyzes, or generates sound on the fly needs a lower-level API. Text-to-speech, speech-to-speech translation, synthesizers, and music visualization aren't possible without access to audio data.

We can expect the standard audio API to work well with microphone input from the data element as well as files included with audio tags. With <device> and an audio data API, you may be able to make an HTML5 application that allows users to record and edit sound from within a page. Audio clips will be able to be stored in local browser storage and reused and combined with canvas-based editing tools.

Presently, Mozilla has an experimental implementation available in nightly builds. The Mozilla audio data API could act as a starting point for standard cross-browser audio programming capabilities.

Touchscreen Device Events

As Web access shifts ever more from desktops and laptops to mobile phones and tablets, HTML5 is also continuing to adapt with changes in interaction handling. When Apple introduced the iPhone, it also introduced into its browser a set of special events that could be used to handle multitouch inputs and device rotation. Although these events have not yet been standardized, they are being picked up by other vendors of mobile devices. Learning them today will allow you to optimize your web applications for the most popular devices now.

Orientation

The simplest event to handle on a mobile device is the orientation event. The orientation event can be added to the document body:

<body onorientationchange="rotateDisplay();">

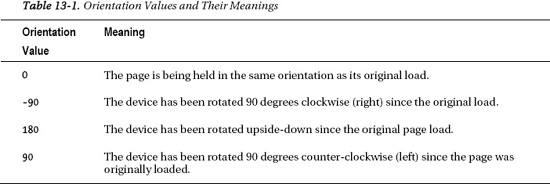

In the event handler for the orientation change, your code can reference the window.orientation property. This property will give one of the rotation values shown in Table 13-1, which is relative to the orientation the device was in when the page was initially loaded.

Once the orientation is known, you can choose to adjust the content accordingly.

Gestures

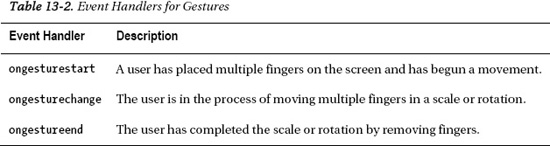

The next type of event supported by mobile devices is a high-level event known as the gesture. Consider gesture events as representing a multitouch change in size or rotation. This is usually performed when the user places two or more fingers on the screen simultaneously and pinches or twists. A twist represents a rotation, while a pinch in or out represents a zoom out or in, respectively. To receive gesture events, your code needs to register one of the handlers shown in Table 13-2.

During the gesture, the event handler is free to check the rotation and scale properties of the corresponding event and update the display accordingly. Listing 13-1 shows an example usage of the gesture handlers.

Listing 13-1. Example Gesture Handler

function gestureChange(event) {

// Retrieve the amount of change in scale caused by the user gesture

// Consider a value of 1.0 to represent the original size, while smaller

// numbers represent a zoom in and larger numbers represent a zoom

// out, based on the ratio of the scale value

var scale = event.scale;

// Retrieve the amount of change in rotation caused by the user gesture

// The rotation value is in degrees from 0 to 360, where positive values

// indicate a rotation clockwise and negative values indicate a counter-

// clockwise rotation

var rotation = event.rotation;

// Update the display based on the rotation.

}

// register our gesture change listener on a document node

node.addEventListener("gesturechange", gestureChange, false);

Gesture events are particularly appropriate in applications that need to manipulate objects or displays, such as in diagramming tools or navigation tools.

Touches

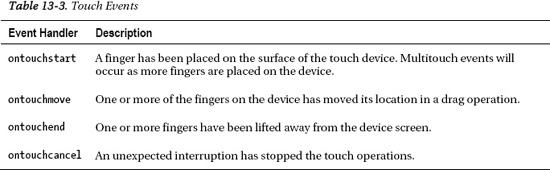

For those cases where you need low-level control over device events, the touch events provide as much information as you will likely need. Table 13-3 shows the different touch events.

Unlike the other mobile device events, the touch events need to represent that there are multiple points of data—the many potential fingers—present at the same time. As such, the API for touch handling is a little bit more complex as shown in Listing 13-2.

Listing 13-2. Touch API

function touchMove(event) {

// the touches list contains an entry for every finger currently touching the screen

var touches = event.touches;

// the changedTouches list contains only those finger touches modified at this

// moment in time, either by being added, removed, or repositioned

varchangedTouches = event.changedTouches;

// targetTouches contains only those touches which are placed in the node

// where this listener is registered

vartargetTouches = event.targetTouches;

// once you have the touches you'd like to track, you can reference

// most attributes you would normally get from other event objects

varfirstTouch = touches[0];

varfirstTouchX = firstTouch.pageX;

varfirstTouchY = firstTouch.pageY;

}

// register one of the touch listeners for our example

node.addEventListener("touchmove", touchMove, false);

You may find that the device's native event handling interferes with your handling of the touch and gesture events. In those cases, you should make the following call:

event.preventDefault();

This overrides the behavior of the default browser interface and handles the event yourself. Until the mobile events are standardized, it is recommended that you consult the documentation of the devices you are targeting with your application.

Peer-to-Peer Networking

We haven't seen the end of advanced networking in web applications either. With both HTTP and WebSocket, there is a client (the browser or other user agent) and a server (the host of the URL). Peer-to-peer (P2P) networking allows clients to communicate directly. This is often more efficient than sending all data through a server. Efficiency, of course, reduces hosting costs and improves application performance. P2P should make for faster multiplayer games and collaboration software.

Another immediate application for P2P combined with the device element is efficient video chat in HTML5. In peer-to-peer video chat, conversation partners would be able to send data directly to each other without routing through a central server. Outside of HTML5, P2P video chat has been wildly popular in applications like Skype. Because of the high bandwidth required by streaming video, it is likely that neither of those applications would have been possible without peer-to-peer communication.

Browser vendors are already experimenting with P2P networking, such as Opera's Unite technology, which hosts a simplified web server directly in the browser. Opera Unite lets users create and expose services to their peers for chatting, file sharing, and document collaboration.

Of course, P2P networking for the web will require a protocol that takes security and network intermediaries into consideration as well as an API for developers to program against.

Ultimate Direction

So far, we have focused on empowering developers to build powerful HTML5 applications. A different perspective is to consider how HTML5 empowers users of web applications. Many HTML5 features allow you to remove or reduce the complexity of scripts and perform feats that previously required plugins. HTML5 video, for example, lets you specify controls, autoplay, buffering behavior, and a placeholder image without any JavaScript. With CSS3, you can move animation and effects from scripts to styles. This declarative code makes applications more amenable to user styles and ultimately returns power to the people who use your creations every day.

You've seen how the development tools in all the modern browsers are exposing information about HTML5 features like storage, as well as critically important JavaScript debugging, profiling, and command-line evaluation. HTML5 development will trend toward simplicity, declarative code, and lightweight tools within the browsers or web applications themselves.

Google feels confident enough about the continuing evolution of HTML that it has released the Google Chrome operating system, a streamlined operating system built around a browser and media player. Google's operating system aims to include enough functionality using HTML APIs to provide a compelling user experience where applications are delivered using the standardized web infrastructure. Similarly, Microsoft has announced that Windows 8 will not support any plugins in the new Metro mode, including the company's own Silverlight plugin.

Summary

In this book, you have learned how to use powerful HTML5 APIs. Use them wisely!

In this final chapter, we have given you a glimpse of some of the things that are coming, such as 3D graphics, the new device element, touch events, and P2P networking. Development of HTML5 shows no sign of slowing down and will be very exciting to watch.

Think back for a minute. For those of you who have been surfing the Web, or perhaps even developing for it for ten years or more, consider how far HTML technology has come in just the last few years. Ten years ago, “professional HTML programming” meant learning to use the new features of HTML 4. Cutting edge developers at the time were just discovering dynamic page updates and XMLHttpRequests. The term “Ajax” was still years from introduction, even if the techniques Ajax described were starting to gain traction. Much of the professional programming in browsers was written to wrangle frames and manipulate image maps.

Today, functions that took pages of script can be performed with just markup. Multiple new methods for communication and interaction are now available to all those willing to download one of the many free HTML5 browsers, crack open their favorite text editors, and try their hands at professional HTML5 programming.

We hope you have enjoyed this exploration of web development, and we hope it has inspired your creativity. We look forward to writing about the innovations you create using HTML5 a decade from now.