Marketing and selling

This section discusses the branding, marketing, and selling of designers and the products they produce—from working with brand DNA and market research, to the role of packaging and retail design.

Branding

The products we use and consume say a great deal about our individual tastes and personalities. A brand is an amalgam of product design, logos, slogans, advertising, marketing, packaging, and consumer recognition. Designers need to ensure that their designs inspire an emotional resonance in consumers, encouraging them to develop a relationship with a brand or product line that evolves over a lifetime of purchasing.

Consumers are drawn to brands because they embody values they are attracted to, such as authenticity or exclusivity. Brands create mythologies about their past, such as Coca-Cola® promoting that it is “the real thing.” The purchase of up-market “designer” goods positions the buyer in a social hierarchy through conspicuous consumption.

While brands are created by designers and marketing executives, they are living, evolving entities that are constantly subjected to alteration by consumers, for example, in the phenomenon of “IKEA hacking,” where an IKEA product becomes the basis for the consumer’s own product, the rationale being that the product is cheaper than the raw materials.

Glossary of branding and marketing terms

- Brand values—The essential guiding principles and rules of a brand.

- Brand image—The look, feel, and impression generated by a brand’s logo, products, retail environments, advertising, marketing, and customer service.

- Brandscape—The visual environment and marketplace that products and brands exist within.

- Brand DNA—The design language, visual codes, and signifiers that embody a brand.

- Brand guidelines—The documents produced by companies to assure the consistent tone and use of brand values and identity.

- Brand manager—The person responsible for actively managing the brand image.

Pimp My Billy: Billy Wilder, by Ding3000, 2005. Thirty-five million units have been sold worldwide, making it the world’s biggest seller when it comes to shelves. The design enables buyers to customize each shelf, inspiring a DIY design craze known as “IKEA hacking.”

Consuming design

A visitor to a contemporary department store cannot avoid being dazzled by the plethora of products on sale, with each type of product coming in an enormous variety of styles. Equally bemusing is the advertising mythology surrounding them. For example, customers are led to believe that buying a Dualit toaster will not only mean better toast, but also a better life. Few really believe that nirvana comes with a new toaster or shaver, but the advertisers continue to succeed in persuading us that these are essential lifestyle purchases.

In contemporary society it could be argued that our possessions represent what we are. Lifestyle magazines reinforce this belief. Over and above any operational usefulness products may have, all goods act as part of an elaborate display, reinforcing identity and sending messages to others “like us.” More important than the possession of an item are the details—the minutiae of appearance, the well-developed visual styles—that carry the messages of the taste cultures or dress codes.

Trying to identify and classify these styles is a highly challenging task for a designer, but the successful commercial brands and “household name” have, without exception, developed an identifiable “house style” or “brand” consisting of aesthetic codes and data that make up the brand’s design “DNA.” These carefully nurtured and constantly evolving visual languages enable designers to communicate their ideology, with their portfolio of products resembling physical manifestos for each taste culture.

Bling Bling, by Frank Tjepkema for Chi Ha Paura, 2002. This medallion critiques our consumer obsession with brands, and how shopping has become our new religion in a secular age.

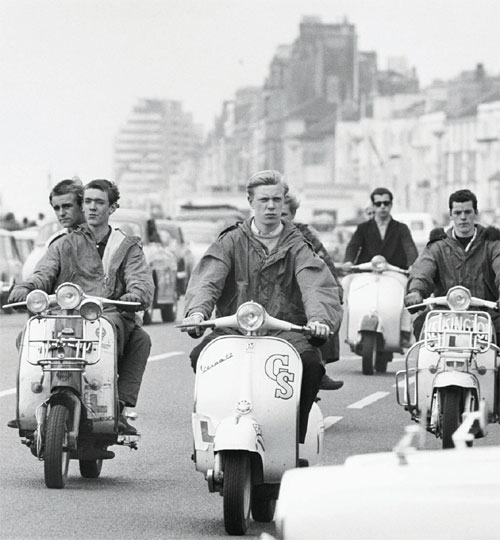

Mods ride their scooters along the seafront at East Sussex, England,, 1964. Arguably the first subculture to openly consume design, their way of life was expressed through a carefully coded set of clothes and products such as bespoke suits, parkas, and motor scooters.

Porsche has carefully evolved their brand over 60 years. Comparing the product lineup from 1956 and 2010, one can see clearly how a brand’s visual language can be developed, stretched, and applied to a variety of models within a product range.

Design as brand

Any design is capable of absorbing meanings and values from other sources, even if these are not intrinsic to the design itself. Design branding is an approach to design that demands that the entire design, not just the logo or features, should be regarded as the brand’s identity. Successful design branding is about increasing the symbolic power of a design by making it work harder, more actively, to communicate the right values, rather than leaving it to time and chance. A prime example of this is Porsche, which has developed a visual language that is applicable to accessories such as sunglasses as well as the iconic sports cars it produces.

A brand’s identity should not be set in stone. Brands are living entities, and brand managements should be ready to embrace new visions, new structures, new shapes, and new textures in response to changing consumer attitudes and changing technology—while always staying true to the brand’s core values. At the heart of successful product design should be a strong idea to communicate the proposition driven by the brand’s personality, through an evolving and dynamic visual language.

Designer as brand

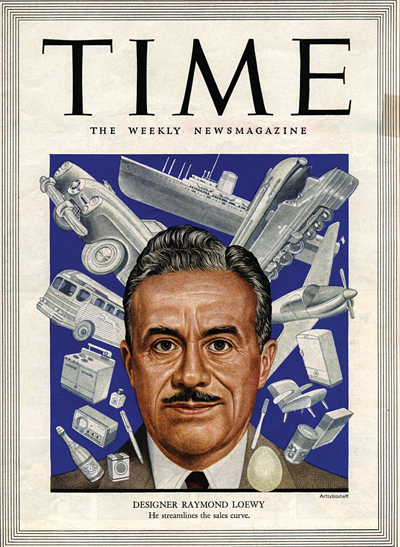

The first designer who achieved superstardom was American industrial designer Raymond Loewy (see Chapter 1), who was responsible for the Avanti car, and for the ffirst major redesign of the origina Coca-Cola® bottle. Featured on the cover of Time magazine in 1949 with the slogan “he streamlines the sales curve,” Loewy was the first designer to realize that consumers perceive products to possess personalities and identities, and that the personality of a product could be the personality of the designer.

Designers were not slow to follow in his footsteps, and the phenomenon of the celebrity designer reached its zenith during the 1980s when Philippe Starck (see Chapter 1), the enfant terrible of French design, became a household name, capable of turning his creative eye and signature to a dazzling range of products such as the Juicy Salif lemon squeezer and Bubble Club sofa. His commercial bankability was such that he could even convince leading manufacturers to develop a sub-brand featuring the creative input and signature of his young daughter, Ara.

The cult of personality is such that the design industry, fueled by the design media, has elevated designers to such heights that it is possible to lose sight of the need to produce actual products, not just objects that demonstrate our designer awareness, taste, and wealth. Our obsession with designer labels and celebrity design has produced many commercial casualties. Young and emerging designers need to refocus their efforts and develop sustainable careers rather than risk deluding themselves that it’s all about becoming the next big thing.

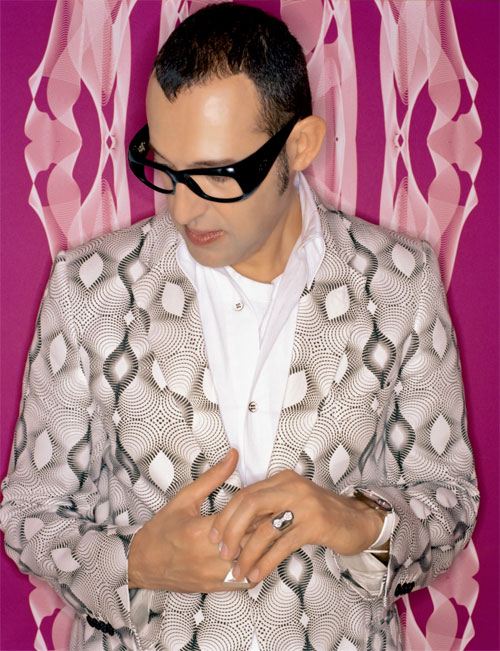

Designers are often keen to promote themselves as a brand in itself, creating a cult of personality. New York-based designer Karim Rashid has carefully constructed a media identity where his products and personality are one and the same.

Design as brand language

It is critical to be aware of the “design language” employed in the sector you are working in and the brand values within that sector. A brand value must be high in both resonance and contribution. In other words, it must enjoy a high level of recognition in the target market, and also actively contribute to a product’s meaning.

Alongside brand values, there are signifiers and identifiers—high in resonance and able to signify membership of a particular category or identify a particular brand, but low or lacking in active contribution beyond these basic levels. At the lowest level of brand language are generics and passengers: visual elements that may not be remembered and that signify and contribute nothing; they are simply there and might just as well not be there.

Treat a brand’s DNA with respect, but do not necessarily treat it as a fixed and sacrosanct design element. Once you have understood its value there may be better ways of communicating this more strongly. The key is to build on the DNA, not blindly preserve it, as this can result in a brand losing relevance and resonance in the market over time. Brand values do not exist in isolation but rather in relationship with other elements, and with the brand’s identity in a broader competitive context. This context is in a constant state of flux, as is the way the product is decoded by the consumer.

Raymond Loewy was the first product designer who became a household name. He was featured on the cover of Time magazine, 1949, promoting his famous MAYA design principle, creating the “Most advanced yet acceptable” designs with great commercial and critical success.

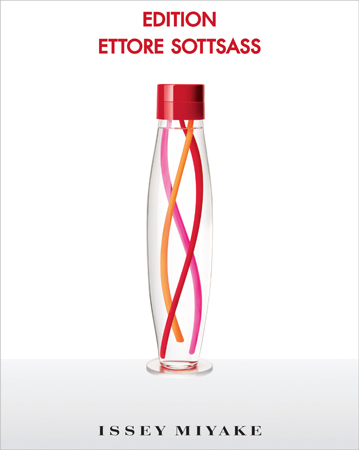

L’Eau d’Issey—Edition Ettore Sottsass, 2009.

Packaging

Packaging is a thriving sector of design today, from graphic designers creating eye-catching boxes to structural packaging designers specializing in the bottle and container. The role of packaging is not restricted to merely protecting the contents of a package, but also includes helping sell a product at the point of purchase and promoting a product’s attributes and benefits.

Many products are meaningless without their packaging, as generic products, foods, or materials require a branded package to differentiate their contents. The retail environment plays a vital role in creating a branded experience that builds upon the message being conveyed by the product and its packaging.

Acting upon consumers’ conscious and subconscious wants, needs, and desires, the retail environment can become a highly crafted brandscape that has as dramatic an effect on consumers’ perceptions of a brand as the quality and nature of the products themselves.

CASE STUDY: Apple’s visual language

Apple has established itself as a leader in product design in terms of its visual language, as much as its technology. From beige to candy to minimalist and beyond, its story has evolved from the 1980s to today.

Beige stage

The original 1984 Apple Macintosh, with its minimal detailing and integrated screen, was the result of Apple founder Steve Jobs declaring that the then market leader in computing, IBM, had it all wrong, selling personal computers as data-processing machines, not as tools for the individual.

The Macintosh, with its all-in-one beige box designed by Hartmur Esslinger of frog design, rejected the “black box” business aesthetic of IBM and instead conceived a user-friendly product that would be small enough to fit within the home and present an image that was more helpful friend than technological foe. The Mac was famously launched on television in a spectacular advertisement, created by leading film director Ridley Scott, that aimed to show an individual “breaking the mold.” This set the tone for Apple’s non-conformist, highly sophisticated, and enduring design language, which encompasses product, brand, and company.

Original Macintosh, 1984.

Candy stage

Steve Jobs left Apple in the late 1980s and the company floundered during the 1990s, losing market share until its very survival was threatened. In 1996 Jobs returned, determined to return Apple to its former creative and commercial glory. His first act was to recognize that Esslinger’s beige aesthetic and visual language was no longer appropriate. He promoted Jonathan Ive, a young designer within the company, to create a new Mac that could reclaim Apple’s heritage of user-friendliness in both form and interface.

The result was the iconic iMac, launched in 1997. Featuring a highly distinctive, highly playful, and toy-like translucent “bondi” blue and frosted white casing, it was an instant marketing and commercial hit that led to a range of copycat designs from companies producing everything from kettles to staplers. However, Apple sensed that they then needed to adopt a more restrained aesthetic for their maturing customers and launched a new stage of their evolution in 2001.

Original iMac, 1998.

Minimalist stage

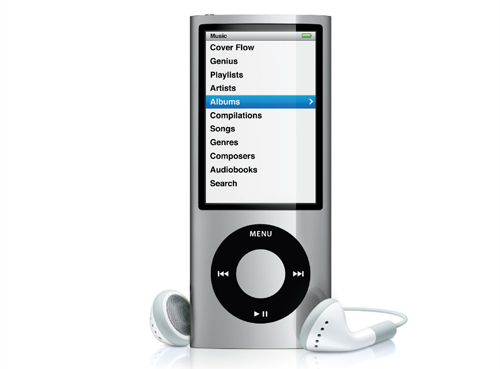

Apple was among the first manufacturers to see that product and content were set to merge. The iPod MP3 player, and accompanying iTunes software, revolutionized the way people downloaded and listened to music. This iconic, lightweight, pocket-sized design has evolved into the designer “must have” iPhone, a device that reflects contemporary society’s obsession with product convergence, combining a phone, portable web browser, MP3 player, and application portal. The iPod’s original form revolutionized how people perceived products, turning technology into jewelery. While the touch wheel interface enabled users to quickly and intuitively scroll through an entire music collection, the shuffle mode allowed for a personal jukebox experience.

The minimalist purity of the iPod, and of Apple’s contemporaneous laptops and desktop computers, presented a cold “masculine” aesthetic that spoke of maturity, rational technology, and an obsessive attention to detail that radiated a confidence to and from its owner. The iPod’s color and material palette of white, aluminum, and chrome sought to signify a futuristic aesthetic that draws upon post-war design. The iPod closely resembles Dieter Rams’ 1958 T3 pocket radio for Braun. Rams is famous for saying that “Good design is like an English butler,” and given Apple’s continued focus on user-friendliness, it is appropriate that Ive draws inspiration from his design hero while seeking to develop the next stage in the evolution of Apple’s visual language.

T3 Pocket Radio, by Dieter Rams for Braun, 1958.

iPod nano, 2009.

iMac 27-inch LED 16:9 widescreen computer, 2009.

Marketing

Traditionally, research focused on the early stages of the design process to develop a PDS, but it is now broadly recognized by the industry that research can play an important role throughout a product’s life cycle. While a designer’s intuition will always remain vital to the design process, sustained and rigorous research can often lead to surprising, counter-intuitive results, identifying new possibilities and helping designers to avoid derivative design directions.

The innovative research techniques described in Chapter 2 are ideal for all stages of the research process and provide viable methods for consulting “real people” about a product design. There are also specific techniques that can prove highly useful during the marketing stage.

Market research techniques

Here are the key points for researching category and brand values within a focus group:

Drawing from memory

Give test consumers blank paper and have them draw particular branded products from memory. Then discuss with the group what each of them has drawn and why.

Camouflage

Modify a series of existing designs, each with different elements removed. Use your focus group to discuss the saliency of differing visual elements. The disappearance of some elements may cause the perception of a brand to alter.

Name swapping

Swap the names and logos on different designs from the same market, then discuss if and why the resulting designs are “wrong” for the brands.

Image and mood boards

Prepare a series of image and mood boards portraying a range of potential directions. It is important to go beyond the obvious, and keep the boards credible in the context of the brand.

Perceptual mapping

By doing these exercises you will be in a position to create a perceptual map where the use of an XY axis enables you to arrange the category visually using comparator terms such as cost, quality, and impact.

Trend forecasting

Product designers need to continually strive to understand what their current and target customers want, how they use a product, and to forecast what the customer will desire next season and beyond. The gestation time to bring a product to market is such that the global conditions impacting on its success can alter from conception to product launch. With stock-market crashes, sociocultural trends, and fashion moving so fast, expert research into future trends is becoming ever more important to the design industry and process. Trend forecasters and futurologists (specialists who postulate possible futures by evaluating past and present trends) are commonly working in timescales of eighteen months in advance, in rapid turnover fields such as textiles, to ten years or more in areas such as car design.

A note of caution is perhaps required here: although market and trend analysis is a very useful tool, designers and companies should not put all their eggs in one basket. Some innovative products are very hard to market research as they ask people to project beyond their experience, where they find it difficult to provide revealing answers to situations or products they have never encountered or even imagined.

The marketing mix

Once market research has been undertaken, there are a number of ways you can help bring a product to market. A common technique to analyze these is the “Seven Ps of Marketing.” In order to ensure that your product or products are aligned with your business strategy, you should explore each of the following components to help you achieve a successful blend of marketing:

Product: You need to ensure that you can identify and communicate what features and benefits your product has over its competitors. This is commonly described as your Unique Selling Proposition (USP).

Place: Where is your product sold to customers and how is it transported and distributed?

Price: How much can you charge for your product in the market based on its development, manufacturing, and marketing costs and its perceived value to customers and users?

Promotion: How will you make your potential customers and users aware of your product and what it offers?

People: You, your staff, and those that represent you and your product. You should remember that good customer service builds customer loyalty.

Process: Can the methods and techniques that you use to design and produce your product have a role in helping build your brand?

Physical environment: Every environment you work within, and those your product/s are sited within, from your workplace to your showroom or retail environment, can make a positive or negative impression on your customers, suppliers, and staff.

Once you have explored these possibilities in detail, you will be ready to write a marketing plan. This will outline your intentions and the means you will use to achieve all your business objectives. You should list all the tasks, deadlines, and individuals responsible, and determine the costs associated with achieving these tasks. By regularly monitoring and reviewing your progress against your detailed plan you can ensure the business develops as planned, changes of direction are discussed and made if required, and, importantly, ensure that you stay firmly within budget.

Conclusion

In conclusion, developing a product and bringing it to market requires a complex series of interconnected activities that place considerable creative, managerial, and administrative demands upon the designer. Contemporary design practice sees designers tackling the entire life cycle of a product, from manufacturing to packaging to point of sale to point of use. Consumers are even getting in on the act and designing their own products through interactive websites such as Nike ID.

Mastering these design phases can take a lifetime, but the process is continually creative and fascinating, and involves addressing a number of issues impacting on design today, from product disposal, recycling, and afterlife to producing designs that move beyond mere function and incite emotional desire and engagement.