Maintaining State

HTTP is a stateless protocol, which means that once a web server completes a client’s request for a web page, the connection between the two goes away. In other words, there is no way for a server to recognize that a sequence of requests all originate from the same client.

State is useful, though. You can’t build a shopping-cart application, for example, if you can’t keep track of a sequence of requests from a single user. You need to know when a user adds items to the cart or removes them, and what’s in the cart when the user decides to check out.

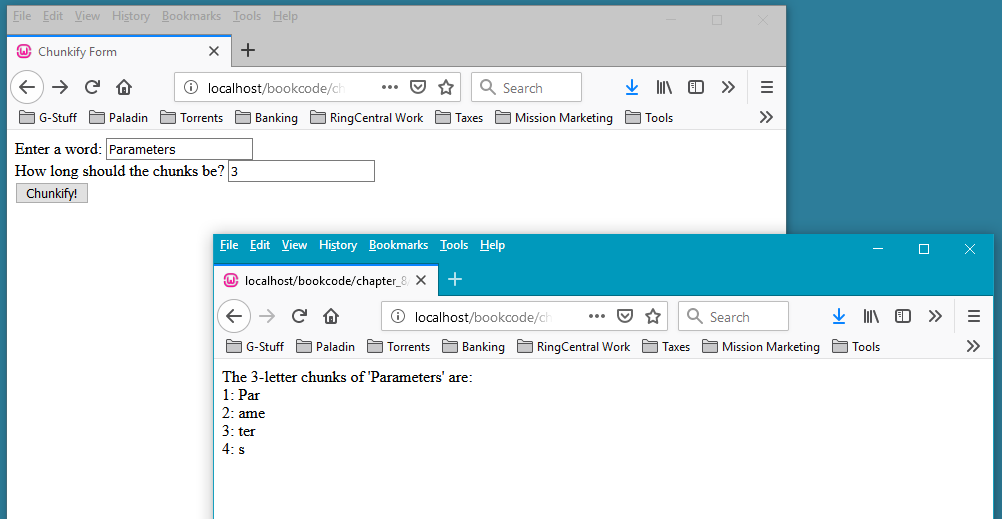

To get around the web’s lack of state, programmers have come up with many tricks to track state information between requests (also known as session tracking). One such technique is to use hidden form fields to pass around information. PHP treats hidden form fields just like normal form fields, so the values are available in the $_GET and $_POST arrays. Using hidden form fields, you can pass around the entire contents of a shopping cart. However, it’s more common to assign each user a unique identifier and pass the ID around using a single hidden form field. While hidden form fields work in all browsers, they work only for a sequence of dynamically generated forms, so they aren’t as generally useful as some other techniques.

Another technique is URL rewriting, where every local URL on which the user might click is dynamically modified to include extra information. This extra information is often specified as a parameter in the URL. For example, if you assign every user a unique ID, you might include that ID in all URLs, as follows:

http://www.example.com/catalog.php?userid=123

If you make sure to dynamically modify all local links to include a user ID, you can now keep track of individual users in your application. URL rewriting works for all dynamically generated documents, not just forms, but actually performing the rewriting can be tedious.

The third and most widespread technique for maintaining state is to use cookies. A cookie is a bit of information that the server can give to a client. On every subsequent request the client will give that information back to the server, thus identifying itself. Cookies are useful for retaining information through repeated visits by a browser, but they’re not without their own problems. The main issue is that most browsers allow users to disable cookies. So any application that uses cookies for state maintenance needs to use another technique as a fallback mechanism. We’ll discuss cookies in more detail shortly.

The best way to maintain state with PHP is to use the built-in session-tracking system. This system lets you create persistent variables that are accessible from different pages of your application, as well as in different visits to the site by the same user. Behind the scenes, PHP’s session-tracking mechanism uses cookies (or URLs) to elegantly solve most problems that require state, taking care of all the details for you. We’ll cover PHP’s session-tracking system in detail later in this chapter.

Cookies

A cookie is basically a string that contains several fields. A server can send one or more cookies to a browser in the headers of a response. Some of the cookie’s fields indicate the pages for which the browser should send the cookie as part of the request. The value field of the cookie is the payload—servers can store any data they like there (within limits), such as a unique code identifying the user, preferences, and the like.

Use the setcookie() function to send a cookie to the browser:

setcookie(name [, value [, expires [, path [, domain [, secure [, httponly ]]]]]]);

This function creates the cookie string from the given arguments and creates a Cookie header with that string as its value. Because cookies are sent as headers in the response, setcookie() must be called before any of the body of the document is sent. The parameters of setcookie() are:

- name

- A unique name for a particular cookie. You can have multiple cookies with different names and attributes. The name must not contain whitespace or semicolons.

- value

- The arbitrary string value attached to this cookie. The original Netscape specification limited the total size of a cookie (including name, expiration date, and other information) to 4 KB, so while there’s no specific limit on the size of a cookie value, it probably can’t be much larger than 3.5 KB.

- expires

- The expiration date for this cookie. If no expiration date is specified, the browser saves the cookie in memory and not on disk. When the browser exits, the cookie disappears. The expiration date is specified as the number of seconds since midnight, January 1, 1970 (GMT). For example, pass

time() + 60 * 60 * 2to expire the cookie in two hours’ time. - path

- The browser will return the cookie only for URLs below this path. The default is the directory in which the current page resides. For example, if /store/front/cart.php sets a cookie and doesn’t specify a path, the cookie will be sent back to the server for all pages whose URL path starts with /store/front/.

- domain

- The browser will return the cookie only for URLs within this domain. The default is the server hostname.

- secure

- The browser will transmit the cookie only over https connections. The default is

false, meaning that it’s OK to send the cookie over insecure connections. - httponly

- If this parameter is set to

TRUE, the cookie will be available only via the HTTP protocol, and thus inaccessible via other means like JavaScript. Whether this allows for a more secure cookie is still up for debate, so use this parameter cautiously and test well.

The setcookie() function also has an alternate syntax:

setcookie ($name [, $value = "" [, $options = [] ]] )

where $options is an array that holds the other parameters following the $value content. This saves a little on the code line length for the setcookie() function, but the $options array will have to be built prior to its use, so there is a trade-off of sorts in play.

When a browser sends a cookie back to the server, you can access that cookie through the $_COOKIE array. The key is the cookie name, and the value is the cookie’s value field. For instance, the following code at the top of a page keeps track of the number of times the page has been accessed by this client:

$pageAccesses = $_COOKIE['accesses'];

setcookie('accesses', ++$pageAccesses);

When cookies are decoded, any periods (.) in a cookie’s name are turned into underscores. For instance, a cookie named tip.top is accessible as $_COOKIE['tip_top'].

Let’s take a look at cookies in action. First, Example 8-10 shows an HTML page that gives a range of options for background and foreground colors.

Example 8-10. Preference selection (colors.php)

<html> <head><title>Set Your Preferences</title></head> <body> <form action="prefs.php" method="post"> <p>Background: <select name="background"> <option value="black">Black</option> <option value="white">White</option> <option value="red">Red</option> <option value="blue">Blue</option> </select><br /> Foreground: <select name="foreground"> <option value="black">Black</option> <option value="white">White</option> <option value="red">Red</option> <option value="blue">Blue</option> </select></p> <input type="submit" value="Change Preferences"> </form> </body> </html>

The form in Example 8-10 submits to the PHP script prefs.php, which is shown in Example 8-11. This script then sets cookies for the color preferences specified in the form. Note that the calls to setcookie() are made after the HTML page is started.

Example 8-11. Setting preferences with cookies (prefs.php)

<html>

<head><title>Preferences Set</title></head>

<body>

<?php

$colors = array(

'black' => "#000000",

'white' => "#ffffff",

'red' => "#ff0000",

'blue' => "#0000ff"

);

$backgroundName = $_POST['background'];

$foregroundName = $_POST['foreground'];

setcookie('bg', $colors[$backgroundName]);

setcookie('fg', $colors[$foregroundName]);

?>

<p>Thank you. Your preferences have been changed to:<br />

Background: <?php echo $backgroundName; ?><br />

Foreground: <?php echo $foregroundName; ?></p>

<p>Click <a href="prefs_demo.php">here</a> to see the preferences

in action.</p>

</body>

</html>

The page created by Example 8-11 contains a link to another page, shown in Example 8-12, that uses the color preferences by accessing the $_COOKIE array.

Example 8-12. Using the color preferences with cookies (prefs_demo.php)

<html> <head><title>Front Door</title></head> <?php $backgroundName = $_COOKIE['bg']; $foregroundName = $_COOKIE['fg']; ?> <body bgcolor="<?php echo $backgroundName; ?>" text="<?php echo $foregroundName; ?>"> <h1>Welcome to the Store</h1> <p>We have many fine products for you to view. Please feel free to browse the aisles and stop an assistant at any time. But remember, you break it you bought it!</p> <p>Would you like to <a href="colors.php">change your preferences?</a></p> </body> </html>

There are plenty of caveats about the use of cookies. Not all clients (browsers) support or accept cookies, and even if the client does support cookies, the user can turn them off. Furthermore, the cookie specification says that no cookie can exceed 4 KB in size, only 20 cookies are allowed per domain, and a total of 300 cookies can be stored on the client side. Some browsers may have higher limits, but you can’t rely on that. Finally, you have no control over when browsers actually expire cookies—if a browser is at capacity and needs to add a new cookie, it may discard a cookie that has not yet expired. You should also be careful of setting cookies to expire quickly. Expiration times rely on the client’s clock being as accurate as yours. Many people do not have their system clocks set accurately, so you can’t rely on rapid expirations.

Despite these limitations, cookies are very useful for retaining information through repeated visits by a browser.

Sessions

PHP has built-in support for sessions, handling all the cookie manipulation for you to provide persistent variables that are accessible from different pages and across multiple visits to the site. Sessions allow you to easily create multipage forms (such as shopping carts), save user authentication information from page to page, and store persistent user preferences on a site.

Each first-time visitor is issued a unique session ID. By default, the session ID is stored in a cookie called PHPSESSID. If the user’s browser does not support cookies or has cookies turned off, the session ID is propagated in URLs within the website.

Every session has a data store associated with it. You can register variables to be loaded from the data store when each page starts and saved back to the data store when the page ends. Registered variables persist between pages, and changes to variables made on one page are visible from others. For example, an “add this to your shopping cart” link can take the user to a page that adds an item to a registered array of items in the cart. This registered array can then be used on another page to display the contents of the cart.

Session basics

Sessions start automatically when a script begins running. A new session ID is generated if necessary, possibly creating a cookie to be sent to the browser, and loads any persistent variables from the store.

You can register a variable with the session by passing the name of the variable to the $_SESSION[] array. For example, here is a basic hit counter:

session_start();

$_SESSION['hits'] = $_SESSION['hits'] + 1;

echo "This page has been viewed {$_SESSION['hits']} times.";

The session_start() function loads registered variables into the associative array $_SESSION. The keys are the variables’ names (e.g., $_SESSION['hits']). If you’re curious, the session_id() function returns the current session ID.

To end a session, call session_destroy(). This removes the data store for the current session, but it doesn’t remove the cookie from the browser cache. This means that, on subsequent visits to sessions-enabled pages, the user will have the same session ID as before the call to session_destroy(), but none of the data.

Example 8-13 shows the code from Example 8-11 rewritten to use sessions instead of manually setting cookies.

Example 8-13. Setting preferences with sessions (prefs_session.php)

<?php session_start(); ?> <html> <head><title>Preferences Set</title></head> <body> <?php $colors = array( 'black' => "#000000", 'white' => "#ffffff", 'red' => "#ff0000", 'blue' => "#0000ff" ); $bg = $colors[$_POST['background']]; $fg = $colors[$_POST['foreground']]; $_SESSION['bg'] = $bg; $_SESSION['fg'] = $fg; ?> <p>Thank you. Your preferences have been changed to:<br /> Background: <?php echo $_POST['background']; ?><br /> Foreground: <?php echo $_POST['foreground']; ?></p> <p>Click <a href="prefs_session_demo.php">here</a> to see the preferences in action.</p> </body> </html>

Example 8-14 shows Example 8-12 rewritten to use sessions. Once the session is started, the $bg and $fg variables are created, and all the script has to do is use them.

Example 8-14. Using preferences from sessions (prefs_session_demo.php)

<?php session_start() ; $backgroundName = $_SESSION['bg'] ; $foregroundName = $_SESSION['fg'] ; ?> <html> <head><title>Front Door</title></head> <body bgcolor="<?php echo $backgroundName; ?>" text="<?php echo $foregroundName; ?>"> <h1>Welcome to the Store</h1> <p>We have many fine products for you to view. Please feel free to browse the aisles and stop an assistant at any time. But remember, you break it you bought it!</p> <p>Would you like to <a href="colors.php">change your preferences?</a></p> </body></html>

To see this change, simply update the action destination in the colors.php file. By default, PHP session ID cookies expire when the browser closes. That is, sessions don’t persist after the browser ceases to exist. To change this, you’ll need to set the session.cookie_lifetime option in php.ini to the lifetime of the cookie in seconds.

Alternatives to cookies

By default, the session ID is passed from page to page in the PHPSESSID cookie. However, PHP’s session system supports two alternatives: form fields and URLs. Passing the session ID via hidden form fields is extremely awkward, as it forces you to make every link between pages to be a form’s submit button. We will not discuss this method further here.

The URL system for passing around the session ID, however, is somewhat more elegant. PHP can rewrite your HTML files, adding the session ID to every relative link. For this to work, though, PHP must be configured with the -enable-trans-id option when compiled. There is a performance penalty for this, as PHP must parse and rewrite every page. Busy sites may wish to stick with cookies, as they do not incur the slowdown caused by page rewriting. In addition, this exposes your session IDs, potentially allowing for man-in-the-middle attacks.

Custom storage

By default, PHP stores session information in files in your server’s temporary directory. Each session’s variables are stored in a separate file. Every variable is serialized into the file in a proprietary format. You can change all of these values in the php.ini file.

You can change the location of the session files by setting the session.save_path value in php.ini. If you are on a shared server with your own installation of PHP, set the directory to somewhere in your own directory tree, so other users on the same machine cannot access your session files.

PHP can store session information in one of two formats in the current session store—either PHP’s built-in format or WDDX. You can change the format by setting the session.serialize_handler value in your php.ini file to either php for the default behavior, or wddx for WDDX format.

Combining Cookies and Sessions

Using a combination of cookies and your own session handler, you can preserve state across visits. Any state that should be forgotten when a user leaves the site, such as which page the user is on, can be left up to PHP’s built-in sessions. Any state that should persist between user visits, such as a unique user ID, can be stored in a cookie. With the user ID, you can retrieve the user’s more permanent state (display preferences, mailing address, etc.) from a permanent store, such as a database.

Example 8-15 allows the user to select text and background colors and stores those values in a cookie. Any visits to the page within the next week send the color values in the cookie.

Example 8-15. Saving state across visits (save_state.php)

<?php

if($_POST['bgcolor']) {

setcookie('bgcolor', $_POST['bgcolor'], time() + (60 * 60 * 24 * 7));

}

if (isset($_COOKIE['bgcolor'])) {

$backgroundName = $_COOKIE['bgcolor'];

}

else if (isset($_POST['bgcolor'])) {

$backgroundName = $_POST['bgcolor'];

}

else {

$backgroundName = "gray";

} ?>

<html>

<head><title>Save It</title></head>

<body bgcolor="<?php echo $backgroundName; ?>">

<form action="<?php echo $_SERVER['PHP_SELF']; ?>" method="POST">

<p>Background color:

<select name="bgcolor">

<option value="gray">Gray</option>

<option value="white">White</option>

<option value="black">Black</option>

<option value="blue">Blue</option>

<option value="green">Green</option>

<option value="red">Red</option>

</select></p>

<input type="submit" />

</form>

</body>

</html>