Chapter 4

Defining the Project Goals

- Defining project goals and objectives

- Agreeing on the deliverables

- Discovering requirements

- Determining assumptions and constraints

- Compiling the project scope statement

- Developing a communications plan

We're off and running! The Initiating process is complete, and we're ready to start the processes in the Planning process group.

The process contained in the Planning process group are some of the most important processes in the project. I think most project managers will contend that a well-documented plan that's managed expertly will drive the project to a successful completion almost all by itself. Almost. Don't forget that you're the one who is responsible for developing the plan — with help from the project team — and later monitoring the project for adherence to the plan. But most of the work in project management is in the Planning process group, so we'll spend many of the remaining chapters of the book discussing planning documents.

This chapter kicks off planning with a definition of goals and project deliverables. From there, we break down these elements into requirements and wrap it all up with the creation of a project scope statement.

Agreeing on the Deliverables

Scope definition is the first thing you'll want to tackle in the Planning process. Defining the scope starts with the goals or objectives of the project and continues to refine them, breaking them down into smaller components until at last the deliverables and requirements are defined at a level where they can be accurately estimated, assigned, and controlled. The end product of scope definition is the publication of the project scope statement, which spells out each of the things I just mentioned, plus a few others we'll cover in the coming sections.

Goals, objectives, deliverables, requirements…what's the difference? These terms sometimes get used interchangeably, but there are some differences. We'll spend the next few sections examining what makes up each of these components and what their differences are.

Goals and Objectives

The title gives this one away. Goals and objectives are very closely related and probably can be used interchangeably without a lot of confusion. Goals and objectives define the “what” it is you're trying to produce or accomplish. They are the reason the project was undertaken.

I like to think of objectives as having a little broader definition than goals. Goals, on the other hand, are more precise and are stated in tangible terms. But let's not get too hung up on goals versus objectives, because objectives are subject to the same criteria as goals if you're using the terms interchangeably.

Let's suppose you've been appointed the project manager for the Logan Street Move project. Your company has purchased a new building and made some extensive renovations, and you're ready to move the existing staff, currently in two different locations in your city, to the new building. The objective for this project might read something like this, “Move the existing staff to the Logan Street location with no disruption in service to our customers.”

Although that's a good objective statement, it really doesn't qualify as a goal. Goals describe what you're trying to do or accomplish or produce by way of this project. When the goals are completed or accomplished, the project is complete. Goals must spell out exactly what's needed to accomplish the project. That means they must be specific enough to use as the criteria to determine whether the project was a success.

From here on out, I'm going to use the term goal, but know that you could use objective just as easily, as long as you follow the guidelines outlined in this section for defining them.

Project goals are the heart and soul of your project. Without a clear, written understanding of what the goals are, folks might take off in all different directions, and, before you know it, you have a project disaster on your hands. At best, you'll find a lot of disgruntled team members and stakeholders mumbling their version of the project goals under their breath (or to your boss) and not understanding why you didn't understand that their version of the goals was the correct version. You don't want to go there.

NOTE Goals describe what your project is going to accomplish or produce.

The Logan Street Move project needs some further definition. Suppose I'm a team member on this project, and I'm working from the objective statement given in the opening of this section. I understand that the move is taking place on two separate days, and I've planned my activities with this understanding in mind. But you, the project manager, know that the move from our two existing locations must occur on the same day. The first problem with this scenario is a lack of communication between the project team and the project manager, but that's another chapter. The second problem is that the goal is not stated clearly enough; it probably wasn't written down nor was it communicated to everyone involved on the project. So let's fix it.

SMART Goals

SMART project managers document the goals of the project and communicate them to all the team members and key stakeholders. You may have seen this acronym before, but it's one that we should review again. Goals should be SMART: specific, measurable, attainable, realistic, and time bound. Each of these is explained in a little more detail here:

S = Specific Goals should be specific and stated in clear, concise terms. This means that if you were to leave the company somewhere in the middle of the project (this is generally not a recommended career move), another project manager would be able to read and understand what the goal is without confusion.

M = Measurable Goals are measurable. The results of the goal are verifiable through some means. This could include everything from complicated formulas and measurements to a simple determination that yes, the result occurred, or no, it did not.

A = Attainable The goal should be attainable for the project team in terms of technology, skills, ability, financial means, and so on. It's reasonable for a goal to be a bit of a stretch for the project team, but if it's beyond their capability, your chances of successfully completing the project and meeting the goal are at risk. You should have a solid understanding of the capabilities of your team members and when outside resources or expertise may be needed in order to assure project success. Goals should also be agreed to. You'll want to gain consensus and agreement from the key stakeholders on the goals of the project. This ensures that everyone understands what the final outcome is and will work toward that end.

R = Realistic Goals must be realistic. If both of the existing offices need to move on the same day to the new facility and there is only one moving van available, the goal is not realistic. (You would discover this problem during the Planning process, and as a result, you would have to come back and revise your goals and thus the scope statement.)

T = Time Bound Goals must have a timeframe that they're completed within, that is, an established end date. Just as projects have a definite end date, so do goals.

Now let's take another stab at writing a goal statement for this project using the criteria we just learned. “Move the existing staff from the Third Street location and from the Washington Street location on March 4 to the new Logan Street location with no disruption in services to our customers.”

This statement meets all the requirements of a goal. It's specific because it states who, when, and where, and it's written clearly and concisely. It's measurable because either the move will occur or it will not. The service-disruption part of the goal statement is measurable also. It's attainable and agreed to by all the key stakeholders. The goal is realistic, and it's time-bound by the March 4 date.

I like having one, over-arching goal for the project such as the one stated in the previous paragraph. In one sentence, this statement conveys exactly what the purpose of the project is and what we hope to accomplish. It's concise and clear. This is a great motivator to print on attractive paper and hang in prime locations where team members, stakeholders, and management will see it often.

NOTE A single goal statement keeps the team focused on the end result of the project. It's the reason that they're assigned project activities — and all project activity should ultimately concern meeting the project goal.

Now that everyone understands the goal of the project, it's time to move on and establish the deliverables.

Deliverables

deliverables

A measurable outcome, measurable result, or specific item that must be produced to consider the project or project phase completed. Deliverables are tangible and can be measured and easily proved.

Deliverables include measurable results, measurable outcomes, or specific products, services, or results that must be produced in order to consider the project complete. Deliverables, like goals, should be specific and measurable.

You can apply the same SMART criteria to deliverables as you do to goals. The clearer and more specific you make the deliverables, the easier it will be to plan and estimate project activities and communicate assignments. Deliverables are like mini-goals in that they describe what it is you're producing or going to accomplish. When all the deliverables are completed, the goal of the project is accomplished.

Now back to the Logan Street Move. Knowing that our goal is to move the staff on a specific day, we can start to document some of the more obvious deliverables needed to make the move happen. Here are a few:

- Contract with a local moving company by January 15.

- Provide boxes and labeling instructions to all employees by February 7.

- Hold weekly town hall meetings to answer questions about the move, starting February 1.

- Meet with the management team by January 7 to explain how seating arrangements should be identified.

- Obtain floor plans from the management team by February 1 showing employee placements.

- Contract with IT specialists by January 15 to coordinate and move network servers, switches, printers, and PCs.

- Move telecom equipment, network servers, switches, printers, and PCs the evening of March 3 starting at 5:01 a.m.

- Connect and test all telecom and network equipment by 6 a.m. on March 4.

Each of these deliverables requires some type of action, and each has a completion date. They are measurable and verifiable and have specific results that will allow you to determine whether the deliverable was completed. Keep in mind that this list does not contain all the deliverables that you'd have for a project like this. I've listed only a few of them here to give you an idea of what they may look like. An actual deliverables list for a project like this would be much more extensive.

You may be thinking that the deliverables for a project like this look fairly easy to come up with, but what about very large, complex projects? Are they all lumped in together or somehow segmented? I'm glad you asked. That leads us right into the next discussion of project phasing.

Phasing Multiple Deliverables

Suppose the executive management team decides that the upcoming move is the perfect opportunity to reorganize the departments and reporting structures, one of their favorite activities (but don't tell them I said that). They're convinced that this activity is part of the overall project, but you as project manager are convinced that it's a separate project. What should you do? Well, you can compromise.

Consider structuring the project, and the project plans, as a project with two phases. The completion of phase 1, the reorg project, becomes a deliverable and an input into phase 2, the move project. Therefore, phase 1 must be completed prior to the activities beginning in phase 2. (But we're getting ahead of ourselves because these are scheduling issues, and we'll cover them in Chapters 8, “Developing the Project Plan.”) I recommend having two goals in this case — one goal for the reorg phase of the project and another goal for the move phase. Deliverables should be associated with the appropriate goals as well.

Many large, complex projects have phased deliverables. For instance, phased projects are very common in the information technology arena. Users might decide that new programs are needed to capture data that's produced as the result of new business processes and equipment. However, because of resource limitations or budget constraints or both, only the most critical pieces of programming can be completed in phase 1. The users, or stakeholders, and the project manager will work through each deliverable, determining which ones are critical to accomplishing the goals of the project and which ones can be delayed to phase 2. If money and resources were no object, the project could be completed all at once, but this is rarely ever the case.

NOTE Excellent project management techniques applied to the wrong goal or deliverables will result in an unsuccessful project.

Keep in mind that no matter how good you are at applying project management techniques and managing your team, if you're working toward the wrong goals or the wrong deliverables, your project will not be successful. It's very important that you spend the time to define the project goals, deliverables, and requirements and then get agreement and sign-off. Our goal for the Logan Street Move project would not be successful if employees arrived on Monday morning and found that they had no computers or telephones to work with. The project couldn't be considered successful because the lack of computers and phones would definitely cause an interruption in customer service.

Discovering Requirements

requirements

The specifications or characteristics of the deliverables that must be met in order to satisfy the needs of the project, broken down to their most basic components.

Requirements are different from goals and deliverables. That is, they help define how we know the goal or deliverable was completed successfully. If our project involved building a new car model, for example, one of the requirements might be body style or paint color.

As you might have guessed, requirements are a further breakdown of the deliverables. Requirements describe the characteristics of the deliverable in very specific detail. For example, suppose one of the deliverables for a new car model is bucket seats. The requirements would include the type of fabric, the model number (Are these bucket seats for a coupe or a pick-up truck?), the color of the fabric, whether the seats are manually adjustable or have electronic controls, the type of headrests, and so on.

One deliverable could have multiple requirements, while another may have only one. Typically, you should define requirements for each deliverable. As the project manager, you should determine whether there's enough information in the deliverable and requirements description to produce the product or service. If not, get your group together for another round of requirements definition.

Defining deliverables and requirements should not be done in a vacuum. This is not the sole responsibility of the project manager. In fact, requirements gathering is primarily a user or stakeholder function. The project manager should facilitate the process, but you really need your customer or stakeholder to tell you what you're building. Many organizations today have business analysts on staff to perform this function. Make friends with your business analyst because they will partner with you throughout the project and will not only assist with gathering requirements but can help assure the business team adheres to the project scope; they can also facilitate testing, quality assurance, mediate issues between the project team and business team, and more.

Requirements-Gathering Process

Gathering requirements should be a group effort. Sometime shortly after the project kickoff meeting, set up a meeting or series of meetings to determine and document the project requirements. The primary stakeholders and key team members are the folks who should attend. Reserve a conference room with a whiteboard and give yourselves plenty of room to spread out.

Remember to set an agenda for the meeting. I also recommend sending a copy of the project charter to all the people who will be attending, several days prior to the meeting. This will give them a chance to review the project objective and begin thinking about requirements. At this point, ask whether other stakeholders need to be identified and included in the process. Now is not the time to forget someone important. There's nothing more frustrating than to have progressed a third of the way through your project activities only to discover that you forgot an important stakeholder back in the beginning and now have a new set of deliverables to deal with and squeeze into the project schedule.

Conducting the Meeting

Once the meeting has begun, review the project charter with the group. Ask for questions and clarify any concerns up front. Make certain, to the best of your ability, that everyone has the same understanding of the goals of the project.

Next, examine the deliverables (if they were defined prior to this meeting). Provide everyone with a printed copy of the list you've compiled so far. If deliverables were not identified prior to this meeting, this is your starting point. Ask the participants to name the major deliverables for the project or identify missing deliverables from the current list, and start writing them down. This is a simple brainstorming session where everyone is encouraged to participate and say anything that comes to mind.

You can use several other techniques, in addition to or in place of brainstorming, to get the requirements process rolling. (These techniques are applicable to determining the major deliverables as well.) One technique is to send surveys to the key stakeholders prior to the meeting, asking them to list their requirements. Or you could use an interview process if there are only a few key stakeholders involved. One of my favorite techniques is the sticky-note process. Everyone in the room is supplied with a sticky-note pad and a marker. Ask the participants to place one, and only one, requirement or deliverable per sticky note, being as precise as they can. You'll act as facilitator and gather the sticky notes, placing them on the whiteboard as they're turned in. Eventually, a pattern will emerge, and you can group similar requirements together, eliminate duplicates, and so on. Tell the stakeholders to not hold back anything. They should list everything they could ever want or dream regarding this project at this stage. We'll discuss more information-gathering techniques in Chapter7, “Assessing Risk.”

NOTE Requirements are the lowest common denominator and cannot be broken down further.

Requirements are the last stop in describing the deliverables and cannot be broken down further. For instance, a requirement for one of the deliverables in the Logan Street Move project might read something like this: “All moving cartons must contain labels on the top and one side.”

Some other examples of requirements for the Logan Street Move are as follows:

- All labels must list the owner's last name and room number in the new building.

- All computer equipment must be packed in specialized containers by the IT contractors.

- Managers must indicate office furniture placement on designated forms.

- All employees must update their ID cards by February 22 in order to access the new building.

- Computer cables for each computer must be placed in a plastic bag and marked with the computer's identification number.

business rule

Constraints to the project that are determined by company policy or institutional regulation.

When you're defining requirements, make certain to take into account environmental factors such as the organization's culture, infrastructure, and business rules and policies. A business rule is something that must occur in a specific fashion or is a result of a policy or regulation. As an example, a business rule for a financial institution might state that all loan requests over a specific amount must be approved by a vice president. A business rule for the building move project might say that only the IT contract employees may move the computers.

Here's where the lines begin to blur between deliverables and requirements. Deliverables may already be broken down to the lowest level, in which case you could consider them either deliverables or requirements. For example, the deliverable we listed earlier called “Connect and test all telecom and network equipment by 6 a.m. March 4” really can't be broken down any further. The “Provide boxes and labeling instructions to all employees by February 7” deliverable, on the other hand, may have requirements associated with it, including “All labels must list the owner's last name and room number in the new building.”

Again, don't get too hung up on deliverables versus requirements. The main point is that you document what needs to be done in order for the project to be successful. Remember that deliverables are the specific items or services that must be produced in order to consider the project successful, and requirements are the specifications of the deliverables or project goals. As long as you've diligently tried to uncover all the deliverables and requirements and then recorded them, you're well on your way to creating better project planning documents. Believe it or not, I've seen projects kicked off and conducted on nothing more than verbal requirements. Should I tell you all the gory details about what happened to those projects and the project managers working on them? No, I didn't think so. Document the deliverables and requirements even if the project is going to take you only a day or two to complete. It eliminates misunderstandings and saves your bacon when the stakeholder comes back and says, “That's not what I wanted.” We'll talk more about that in an upcoming section.

Save Good Ideas for Phase 2

You may discover new deliverables during the requirements-gathering phase or requirements that are considered “nice to haves” but not necessary for the completion of the project. You probably do not have an unlimited budget or unlimited resources, so the next and last step in the requirements-gathering process is to determine which requirements are necessary to meet the goal of the project. All others should be weeded out.

But don't throw them out the window. Document these requirements as the phase 2 portion of the project, or ask the stakeholders to keep them on hand and request a new project when this one's completed. You went through a lot of hard work to flesh out everything desired for the project, so don't let those efforts go to waste. You could also consider filing a copy of the additional requirements in an appendix of your project notebook. This is not something I'd necessarily publish on the intranet, but the additional requirements should be kept somewhere for future reference.

Now let's move on to the more critical issues.

Critical Success Factors

The project deliverables or requirements that absolutely must be completed and must be completed correctly to consider the project a success.

You have one more thing to document regarding your deliverables and requirements, and those are the project's critical success factors. Critical success factors include project deliverables — but not all deliverables are critical success factors. You should gain consensus among your requirements-gathering team and the stakeholders regarding which deliverables and/or requirements are critical success factors and then either document them separately or somehow indicate which ones are the critical success factors.

Some of the things I consider critical success factors for all projects include the following:

- Understanding of and consensus regarding the project goals by key stakeholders, project team, management team, and project manager

- Well-defined scope statement

- Involvement and buy-in from the stakeholders as evidenced by sign-off of the project charter and scope statement documents

- Well-defined project plan (including all the documents that you'd normally see for projects, such as the project schedule, risk management plan, budget and cost baseline, communications plan, and change control procedures)

- The use of established project management practices

Critical success factors should not be overlooked. If circumstances come up later during the project that are outside of your control, forcing a schedule, scope, or quality change, it's important for you to understand which deliverables must be completed and which ones could move to phase 2 if necessary. This is where your critical success factors list comes into play. When you're faced with this circumstance, review the critical success factors with the key stakeholders and project team to make sure that they are still critical to the project, and begin making project plan adjustments and taking corrective action from there.

Some of the critical success factors for the Logan Street Move might include those shown in the following list. Keep in mind that this is not a complete list, just a sample to give you an idea of why these elements were chosen as critical success factors.

- Move telecom equipment, network servers, switches, printers, and desktops the evening of March 3 starting at 5:01 p.m. This is a critical success factor because the goal of the project is to perform the move without disruption to customers. Normal business hours are 8 to 5; therefore, starting at 5:01 prevents disruption. In addition, this activity must start at 5:01, or the team will not have enough time to complete this deliverable and meet the criteria of the next deliverable.

- Connect and test all telecom and network equipment by 6 a.m. March 4. This was chosen as a critical success factor to meet the goal of moving the employees without disrupting service to the customer. All equipment must be tested and up and running prior to the employees reporting for work the next morning. Because all company data, customer contact information, customer files, and such reside on the company servers, it's critical that employees have access to the server via their computers. Equally important is the telecom equipment being set up. Customers call in to the company, so the equipment needs to be up and functioning in order to place and receive calls.

- Computer cables for each computer must be placed in a plastic bag and marked with the computer's identification number. This critical success factor will ensure that the computers are set up in time for employees to report to work, because all the cables and cords will be kept together with proper identification so that the installers know which cables go with which computers.

The following deliverable is not a critical success factor:

- Obtain floor plans from the management team by February 1 showing employee placements. This is not a critical success factor because it doesn't prevent the move from occurring. Furniture and boxes may end up misplaced and on the wrong floors, but since everything that the employees need to access the customer accounts resides on the company servers, access to their books and belongings is not critical to the completion of the project. It may irritate some people if they don't have their things right away, but it isn't critical to providing customer service.

Now, suppose the floor plan mentioned in this noncritical deliverable was also being used by the computer specialists moving and hooking up the computers. In that case, this deliverable now becomes a critical success factor because the specialists are relying on the floor plan to determine where each computer gets placed. I think you're getting the hang of it. Don't, however, make the mistake of assuming that the computer specialists have a network diagram with all the locations marked.

And that brings us to one more piece of documentation for the project scope statement: assumptions and constraints.

Identifying Assumptions and Constraints

Remember the old saying about assumptions? Well, throw it out because in project management, you want to make assumptions, but here's the key. Are you ready? You should document all project assumptions. You'll want to document assumptions regarding people, resources, places, things, or anything that you presume is going to perform in a certain way, be available at a certain time, and so on. This is a critical step that's often missed in the project-planning process. That's too bad because misunderstanding assumptions, or believing something to be true that isn't, can kill your project.

This is an often missed step because we tend to take things for granted, thus assuming business as usual. When you leave work for the evening (assuming you're driving a car), you walk out to your car, put the key in the ignition, and assume that the car is going to start. It's not really something you think about because the car starts every day — that is, until the day you put the key in and nothing happens when you turn it. Then the diagnosis process begins…battery, starter, alternator…or crisis mode sets in. “Oh my, little Sweet Pea is at day care, and I have to be there in 20 minutes!”

Project assumptions work the same way. We're so used to operating a certain way or expecting the A-team to drop what they're doing and lend a hand whenever we need it that we don't think about it, until the day they're not available. Don't skip this step — be certain to define and document your assumptions and communicate them to the project team and stakeholders.

Defining Assumptions

assumptions

Events or actions believed to be true. Project assumptions should always be documented.

Assumptions presume that what you're planning or relying on is true, real, or certain. For example, your project might require someone with special programming skills from the IT department. Your assumption is that this person will be available when needed and will exercise their skill on the activity you assign. Document the assumption that this person will be available when needed. (Oh, it's a good idea to check with that person's functional manager ahead of time to make certain that they will be available when needed.)

Discovering and documenting assumptions works just like the requirements-gathering process. Designate one of your project meetings, or a portion of one of the meetings, to discuss and document project assumptions. Use brainstorming techniques in the meeting to get the juices flowing. You could also interview key stakeholders, the project sponsor, and key members to uncover as many assumptions as you can.

We'll revisit these assumptions again when we get to the risk planning process in Chapters 7. Risks are associated with assumptions in many cases, so if you do a good job defining the assumptions, you'll have a good head start on risk identification. Sometimes it's helpful to have someone outside of the project help with this step because they are not as focused on the details as you are. They may see something you wouldn't.

Assumptions might include any of the following:

- Key project member's availability

- Key project member's performance

- Key project member's skills

- Vendor delivery times

- Vendor performance issues

- Accuracy of the project schedule dates

- Customer involvement on the project

- Customer approvals

OK, let's assume you've documented your assumptions. The next step is to validate and verify them. This means that if you're assuming that a key resource is going to be available to work on the project, you must verify with that person's functional manager that they'll be available at that time.

If you're working with vendors or suppliers on your project, make sure they document and verify their assumptions as well. In fact, if a vendor delivery is one of your critical success factors, make sure they document assumptions concerning that delivery. In the Logan Street Move project, we're relying on a moving contractor to show up on the right day with three trucks at each location and enough workers to load everything and get it moved in one day. Consider putting a clause in the contract that says the moving contractor will pay the cost of hiring temporary laborers or leasing rental trucks if for any reason their own trucks are not available (due to mechanical problems, and so on) or their regular work force is not available (a strike, sick-out, and so on). We'll discuss more situations like this when we talk about risk and risk response plans.

Assumptions should be documented in your project notebook or repository. They will be incorporated into the project scope statement, as you'll see shortly, but it doesn't hurt to copy and paste them into their own document and keep them handy. You should verify and validate these assumptions throughout the course of the Planning process and whenever necessary during the project's Executing and Monitoring and Controlling processes.

Defining Constraints

We talked about constraints in Chapters 1, “Building the Foundation.” Remember that constraints are anything that restricts or dictates the actions of the project team. That can cover a lot of territory. The triple constraints — time, scope, and budget — are the big hitters, and every project has one or two, if not all three, of the triple constraints as a project driver. Many projects in the information technology area, for instance, are driven by time. Projects in the pharmaceutical industry are driven by scope but may have time or budget as a secondary constraint. Scope is a constraint that you shouldn't ignore, because you're working within the confines of the project goal and deliverables.

The Logan Street Move project is constrained by time. You must move on March 4. The secondary constraint for this project is budget — there is a limit to how much you can spend. What you want to do now is to document the project constraints. And yes, you can use the same techniques that we've already discussed for deriving project requirements and assumptions.

Besides the triple constraints, don't overlook constraints like these that can cause problems on your project:

- Lack of commitment from the executive management team or project sponsor. I would consider passing on the opportunity to lead a project with this constraint. You'll have a hard time getting support or resolution of problems. Watch out for this constraint because it can creep up on you later in the project. The sponsor may lose interest because other things have come along that usurp the priority of this project and so on.

- Business interruptions or reorganizations in the midst of the project. This could potentially realign your project resources, leaving you empty-handed.

- Stakeholders who have unrealistic expectations of project outcomes. This constraint is overcome through good project communications and requiring sign-off of the project charter and project scope statement.

- Stakeholders' unrealistic expectations of the project schedule. This is also overcome through good project communications early in the project.

- Lack of skilled resources. This constraint could cause project delays or unfilled deliverables.

- Poor communications. This is a potential project killer. Misunderstandings regarding scope, activity assignments, project schedules, risks, or a long list of other project essentials could cause uncorrectable problems.

- Uncertain economic times or business conditions. Difficulty obtaining funding for projects, resources for projects, and general economic disturbances could restrict the project team.

- Technology. Advances in technology can cause project delays due to lack of knowledge of the new technology, training needs or availability of training, availability of resources with experience in the new technology, and so on.

Constraints, like assumptions, are also documented in the project scope statement. These should be updated as you progress through the project to make adjustments to the constraints you've listed, add new ones that may come up along the way, or delete those that are no longer a constraint. Sometimes you'll find that constraints are also project risks and may need risk response plans. We'll talk more about risks in Chapters 7.

Creating the Project Scope Statement

Documents the project goals and deliverables and serves as a baseline for future project decisions.

Everything we've talked about in this chapter so far — goals and objectives, deliverables, requirements, constraints, and assumptions — goes into the project scope statement. The purpose of the scope statement is to document these items, particularly the goals, deliverables, and requirements, to use as a baseline for the project. As you proceed through the project, you'll be faced with decisions and changes that you'll need to monitor so that they conform to the original scope of the project. In this way, the project scope statement is your map, or baseline, that you use to determine where you're going. If questions come up or changes are proposed, the scope statement is the first place you're going to check to make certain that what's requested is in keeping with the original request.

Creation of the project scope statement is one of your most important duties as a project manager. Accurately quantifying the deliverables and detailing the requirements of the project and then getting agreement and sign-off on these deliverables helps assure project success. Creating the project schedule, which we'll cover in Chapters 8, probably ties in importance with creating the scope statement.

NOTE Creating the project scope statement and project schedule are two of the most important duties that a project manager performs.

The project scope statement establishes a common understanding of the project's purpose among your team members and stakeholders. It contains the criteria you and the stakeholders will use at the end of the project to determine whether the project was completed successfully. The scope statement will assist you later in determining project cost estimates, resource estimates, activity definition, and project schedules.

Contents of the Project Scope Statement

You'll use the project charter and the product description to help you write the project scope statement. It's interesting that this is called a project scope statement when in fact several elements actually make up the project scope statement. It isn't a single statement but several pieces of information contained in one document. If you've followed this chapter in order, most of the work for your project scope statement is already done. You understand the product of the project (from the project charter), you know the goals and deliverables, and you have the assumptions and constraints documented. Now it's a matter of putting it all together in one document.

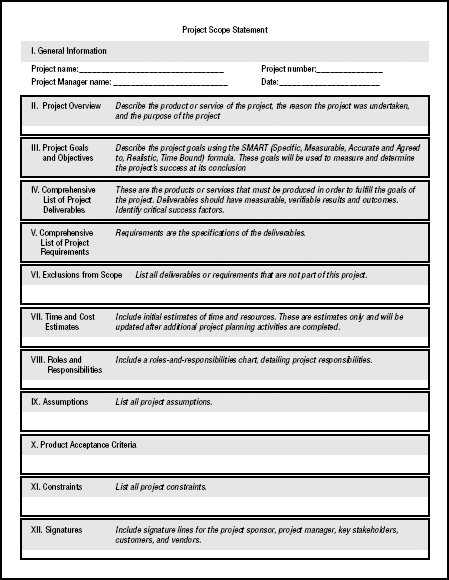

The components of a well-documented project scope statement include the following:

- Project overview, including a description of the product of the project

- Goals of the project (also known as the project completion criteria — did the project produce what we set out to produce?)

- List of project deliverables

- List of project requirements

- List of exclusions from scope (phase 2 deliverables may be mentioned here)

- High-level time and cost estimates

- Roles and responsibilities

- Product acceptance criteria

- Assumptions

- Constraints

We've covered most of these items in detail. We'll talk about time estimates in Chapters 5, “Breaking Down the Project Activities,” and Chapters 8, and we'll cover cost estimates in more detail in Chapters 9, “Budgeting 101.” At this point, if you have high-level information regarding time and cost estimates, include it in the project scope statement with a note explaining that the estimates are not final. These will be refined later when you more clearly define the work of the project.

The list of exclusions from scope, roles and responsibilities, and product acceptance criteria needs a little more explanation.

List of Exclusions

Exclusions are the deliverables or requirements that the team identified as not essential to completing this portion of the project. Exclusions from scope for the Logan Street Move project might include setting up the executive management team's office decoration and furnishings, reorganizing the IT department as a centralized service unit, and so on. It's important to note what's not included in the project so that there's no misunderstanding later when those particular deliverables don't show up or don't get done.

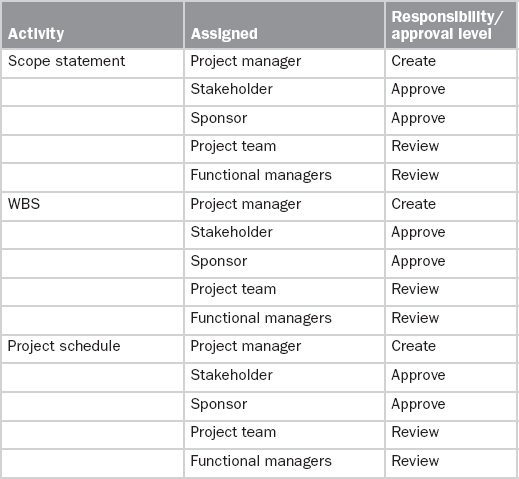

Roles and Responsibilities

The roles and responsibilities section in the project scope statement is much more detailed than what you defined in the project charter. In this section, you identify who is responsible for what. You document who has signing authority, who should review, who should create, and so on. Table 4.1 shows a portion of a sample responsibility chart.

Table 4.1 Roles and responsibilities chart

Product Acceptance Criteria

The section on product acceptance criteria describes the process you'll use for determining how the stakeholders will know that the deliverables and products of the project have been completed satisfactorily and how the stakeholders go about indicating their acceptance. This is usually done with a sign-off document or an email indicating acceptance.

Scope Statement Template

The following graphic pulls everything together. You can use or modify this template for your future project scope statements. It contains all the elements we've talked about so far, plus an area for signatures.

NOTE You can also download a template for the project scope statement from www.sybex.com/go/projectmanagementjumpstart3.

The project scope statement also gets filed in your project notebook or repository and should be published on the project intranet site if you have one.

When your project work is done on contract, the project scope statement can serve as the statement of work (SOW), which was introduced in Chapters 3, “Initiating the Project.” The statement of work is part of the contract. The SOW contains the same details as the scope statement and is used to describe the work of the project in clear, concise terms. You'll specify the product or service required here (the goals of the project) and the deliverables and requirements. Consider adding a list of key stakeholders, an organization chart, timeframes or deadlines, and an initial project schedule to this template if you're using it as a SOW.

The contractor will use the SOW to determine whether they're able to produce the product or service of the project, so it should be as detailed and clear as possible. Either the buyer or the seller can prepare the SOW, but both parties must review and approve it.

Obtaining Sign-off

Does there seem to be a recurring theme throughout the project documents so far? Yes, you're right, there is — describe the nature of the project, the goals, what we hope to accomplish, and obtain sign-off.

The project scope statement, like the project charter, should be signed off. This assures that stakeholders, key management team members, and the project sponsor are all in agreement on the deliverables and requirements of the project. I've witnessed many projects (none of them mine, of course) where the project manager failed to obtain sign-off on the scope statement. And, you guessed it, as the project progressed, memories became very fuzzy and stakeholders thought for sure that requirement X was part of the original plan, while the project manager swore up and down it was part of phase 2. If you cannot resolve this situation and end up having to include the new requirement in this project, it usually means you're going to miss the original planned deadline or run over budget or both. Don't let that happen to you. Document the deliverables and requirements. When a stakeholder comes to you and tries the very famous “I thought that was included,” line (most of them could win an Oscar for their performance delivering this line to you), you can politely point them back to the project scope statement and remind them that, in fact, that requirement is not part of this project.

The next line you'll likely hear is something like, “Well, requirement X has to be included. It's essential to the success of the project.” One of two things is happening here — OK, maybe three. First, the project manager didn't do a thorough enough job gathering requirements, and the stakeholders failed to point out the missing requirements when they reviewed and signed the document. Second, the stakeholder is purposely being a troublemaker and withheld the information during requirements gathering…just because. Third, the stakeholder really never thought about this particular requirement until now. This means you now have a scope change on your hands, and that brings us right to the next section — the project scope management plan.

Creating the Project Scope Management Plan

project scope management plan

Describes how the project scope and work breakdown structure will be defined, describes and documents how project scope is managed throughout the project, including how changes to project scope will be managed.

The project scope management plan describes several processes, including the process that you'll use to define the project scope; how the work breakdown structure will be defined, maintained, and approved (I'll talk more about this topic in Chapters 5); a process that describes how deliverable verification and acceptance will occur; and the process requestors must go through to request changes and how the changes will be incorporated into the project. The project scope management plan also tries to determine the probability of scope changes, their frequency, and their impact. This process will get easier as your experience in project management grows. You'll begin to know what types of changes may occur because of the experience you've gained working on projects where change occurred.

Don't forget to file a copy of the project scope management plan in your project notebook or repository. As you progress through the project, changes to project assumptions, scope, schedules, and so on, make it necessary to repeat some project processes, particularly the planning processes. That's not a bad thing; it's part of applying good project management techniques to your project.

One thing that will most certainly occur on your project is change. How you manage and communicate those changes will determine project success. We'll discuss more about scope changes and the change control processes in Chapter 11, “Controlling the Project Outcome.”

We have one more document to cover in this chapter, and that's the communications plan. Let's take a look at what that entails.

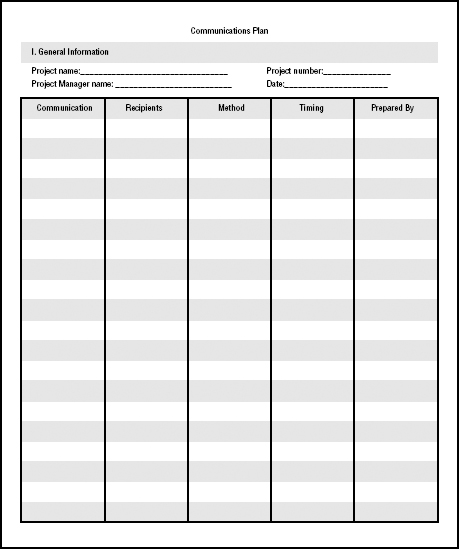

Creating the Communications Plan

communications plan

Documents the types of information needs the stakeholders have, when the information should be distributed, and how the information will be delivered.

We've done quite a bit of documentation already, so it's probably a good time to talk about the communications plan. The communications plan describes who gets what information and when. The who includes stakeholders, project team members, customers, management staff, and others who may have a specific interest or role in your project. The what includes the project documentation, project plans, status reports, status review meetings, project scope statement and scope statement revisions, performance measures, acceptance criteria, change requests, and more. And, of course, the when describes how often the communications are produced, when status review meetings are scheduled, and so on.

The communications plan is documented early in the Planning process. You want to identify all the people who need to know and understand the project progress as early in the project as possible. The communications plan also documents how to collect, file, and archive project communications as well as the distribution methods you'll use to get the information to the stakeholders. This includes how stakeholders can get access to project communication between the established publish dates.

You can create the communications plan in a simple document format listing the who, what, and when, like the example template in the following graphic. Distribute a copy of the plan to everyone listed in the document. This document is a good place to note the location of the intranet site and the types of information that people can access there. This graphic provides a template for the communications plan.

NOTE You can also download the template for the project communications plan from www.sybex.com/go/projectmanagementjumpstart3.

List all the project communications on this template such as status reports, minutes, change requests, the project planning documents, and so on. Identify the people who will receive copies of the communication and how the document will be published. Some information might be distributed via email, others posted to the intranet site, and so on. Note how often the information will be distributed and who is responsible for preparing the information. Post the communications plan to the intranet site or file a copy in the project notebook.

Now that you've created the project scope statement, you're off to the next stop in the Planning process, which is the identification of tasks and activities. We'll cover that and related topics in Chapters 5.

Terms to Know

| assumptions | deliverables |

| business rule | project scope management plan |

| communications plan | project scope statement |

| critical success factors | requirements |

Review Questions

- What criteria should you use to define project goals?

- Describe project deliverables.

- How are requirements different from deliverables or goals?

- What are critical success factors?

- Why are assumptions often overlooked in the project planning process?

- Name three potential constraints for projects other than the triple constraints.

- What is the purpose of a project scope statement?

- What is the purpose of the project scope management plan?

- Why is it important to obtain sign-off of the project scope statement?

- What does the communications plan document?