How to use and implement promotions

From promotional objective to promotional brief

So how do you implement a promotion? You should have an objective (see Chapter 9) and you have also asked for creative input: ‘who do I want to do what?’ (Chapter 4). Now, how do you work out what it can and cannot achieve? And how do you choose between the many techniques available (Chapter 10)?

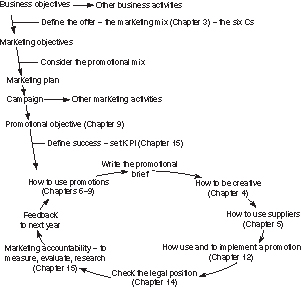

The promotional planning cycle looks like that shown in Figure 12.1, and the stages are dealt with in turn. As you go around the cycle in your promotional career, you’ll find that you get better at each of the six elements.

Figure 12.1 The promotional planning cycle

So, once you have the business and marketing objectives established and know what promotions you are going to do as marketing activities within a campaign, you need to write a short brief.

Whether you intend to devise a promotional offer yourself or to brief someone else, the first stage is the same. It involves setting down the answers to the six questions below, preferably on paper. It is just as valuable to draw up a brief to yourself as it is a brief to someone else. And it should be short – any more than two sides of A4 is long-winded:

1 What is the strategic nature of the brand – its positioning and differential advantage? This will have come from the Offer (Chapter 3).

2 What is the promotional objective? Pick only one – see Chapter 9.

3 Define how you will know it has been a success. Find the particular key performance indicator (KPI) that you need to measure whether you have achieved success. Remember to allocate resources to measure the KPI. Chapter 15 explains why you should set a KPI.

4 Who are the people whose behaviour you want to influence? What are they like, and what interests them? What is their preferred ‘communication canvas’? Revisit Chapter 3 if necessary.

5 What behaviour do you want them to reinforce or change? In other words, what exactly do you want them to do?

6 What are the operational constraints of the promotion – budget, timing, location, product coverage and logistics?

At any given time, it will be possible to specify which of the 12 objectives in Chapter 9 most coincides with both your overall marketing objectives and the campaign of which the promotion forms part. It is vital to get this right. Promotion agencies are sadly familiar with briefs that specify the objectives (often for a small-budget promotion) as ‘to increase trial and repeat purchase, increase loyalty and increase trade distribution’. Desirable as it may be to do all these things, it is difficult to shoot at four goals at once.

If your promotional objective does not overlap with any of the 12 in Chapter 9, it may be that you do not have a promotional brief, but a brief for some other kind of marketing activity – or, indeed, for a rethink of your business as a whole.

Taking the promotional objectives seriously (remember, just like business and marketing objectives, they should be SMART) means quantifying what the promotion is expected to achieve. For example, if the objective is increasing trial, it is important to specify how many trialists are sought, where they are to be found and the quantity of products or services they are expected to consume. Quantifying the objectives at the beginning enables you to measure and monitor the success of the promotion (a subject explored in Chapter 15).

It is now possible to ask the central promotional question: ‘Who do I want to do what?’ This is when you move from the marketing objective to the promotional objective. The transition comes when you start thinking about the people who will help you achieve your marketing objective and the things you want them to do so that you can achieve it.

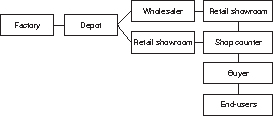

Figure 12.2 shows the movement of a confectionery item from factory to the shopper/buyer. Similar flow charts could be drawn up for the movement of any other product or service; some would be simpler, some more complicated. At each point on the flow chart, there are a number of people. These form the target for promotional activity.

Figure 12.2 Flow chart of the journey of a confectionery item from factory to end-user

In using the flow chart, it is important to ask yourself four questions:

1 Who holds the key to the business problem of delivering the promotion? Is it the retailer? The shopper/buyer or the depot? Is it the end-user (the family)?

2 What are these end-users like? What other things do they do with their time? What are their motivations, interests and desires? What is holding them back from behaving as I would like them to behave? Is it children or friends? Who are they with when they are making the decision that I am interested in – persuading the shopper/buyer (a parent?)?

3 What exactly do I want them to do? Buy one product or more? Use it more frequently or for the first time? Tell their friends about it?

4 Who else on the chain has leverage? Some intermediary? Is it a boss or other staff member? What will persuade the retailer to put it on display?

Achieving behavioural change requires a high level of focus on these questions. It is the point at which marketing thinking moves from the general to the particular. It is no longer a matter of market share, penetration, segmentation and the other abstract categories. It is now about Julie Smith and her son Wayne trying to get the shopping done on a busy Thursday afternoon in Tesco in Birmingham, and spending less than a minute passing the gondola on which your product is located. What will make her choose one brand of vinegar rather than another? Will it be a coupon sent door to door, a Tesco multi-buy or an on-pack offer (if you can persuade Tesco to take it)? Sarson’s vinegar found a particular solution to these questions with its ‘Shake on the Sarson’s’ promotion (Case study 67).

In the office stationery market, it is about the same Julie putting in an order for that week’s needs for the small computer consultancy where she works part time. Julie is now a different kind of customer, taking on the role of a business buyer, not a consumer. What will make her choose one brand of sticky tape over another? Will it be an ‘extra free’ offer, a handy container, a straight discount or a personal benefit for her (if her employers will allow it)? Sellotape’s 10,000 Lottery chances (Case study 53) provides one promotional solution.

In the pub market, it is about the same Julie and her friends having a night out in a large, modern, suburban theme pub. What will encourage her to try out one brand of drink in preference to another? What will encourage her to try another within the limits of safe drinking?

In none of these cases is Julie alone. In the supermarket, she is accompanied by Wayne. At work she is answerable to her boss. In the pub, she is part of a group of friends. The social relationships of mother, employee and friend are very different and have different impacts on the way Julie will make her decision to choose one brand over another. Understanding the relationships and the contexts is crucial to finding the right means of encouraging Julie to do the thing you want her to do.

Thinking through Julie’s needs and interests in relation to your business objectives is the key to promotional creativity, and is the subject of Chapters 2 and 9. How will you evaluate the promotion and know whether or not it is a success? Chapter 15 gives you the answer: set the KPI and measure it, it’s easy.

Promotional mechanics

Thinking about the variety of intermediaries and consumers you may want to influence, and their relationships and lifestyles, creates a bewildering number of options. After all, people are varied. The other side of the coin is the distinctly limited number of mechanics that are available in promotion.

A ‘mechanic’ in promotion refers to the particular things that consumers have got to do – in other words, a competition is a mechanic and so is a free mail-in. There are surprisingly few mechanics available, and all promotions use one or more of them. In many parts of the EU, law further limits the number of mechanics available to you. Objecting to one of them on the grounds that it has been used before is like objecting to a newspaper ad because newspaper ads have been used before.

The creativity and interest of a promotion do not lie in the mechanic itself, but in its relevance to your promotional objectives and to your target market, in the way you tweak it and vary it, in the content of an offer and in the way you put it across. For that reason, mechanics are discussed throughout the rest of the book in the context of actual offers.

Promotions have already been divided into price and value promotions. Mechanics can also be divided into those that impact immediately at the point of purchase and those that give a delayed benefit. Mechanics can then be classified as shown in Table 12.1.

Table 12.1 Classification of promotional mechanics

|

Promotional type |

Immediate |

Delayed |

|

Value |

Free in-packRe-useable containerInstant winHome SamplingFree on-pack |

Free mail-inCompetitionFree drawSelf-liquidatorCharity promotion |

|

Price |

Pence-off flashBuy one, get one freeExtra fill packsIn-store couponFinance offer |

Next purchase couponCash refundCash share-outBuy-back offer |

Table 12.2 matches nine key mechanics to the 12 objectives described in Chapter 9. The matching ranges from 0 (not well matched) to 10 (very well matched). The ratings can be used as a rough guide to suitability. Very often it is the creative execution of a mechanic rather than the mechanic itself that is most effective at creating interest. Clearly, high-cost promotions like immediate free offers are more effective on almost every criterion than low-cost promotions such as self-liquidators.

Table 12.2 Linking the objectives to the mechanics: how they match up

If you have followed this process, you will have a clear promotional objective in mind and you will have had an initial look at the mechanics that could meet it. Now it is time to look at matching the two together in an imaginative and effective way: it is time to see how to be creative.

Implementing the promotion

If you’ve followed the process so far, you will understand the crucial ingredients in devising a promotion. You’ll be clear that for your product or service:

• there’s a marketing objective to be fulfilled for which you can specify a promotional objective, such as increasing volume or gaining trial;

• you know the strategic nature of the brand, its values and the offer in all its elements (the six Cs) and you have researched your customers’ needs and established their communication canvas;

• a promotion, as the part of marketing that focuses on behaviour, is the right answer to a part of the marketing campaign that includes a need to draw attention at a specific time and at a specific place to a marketing activity; a sales promotion is when that time and place is in the retail space;

• you know how to convert the marketing objective into a promotional objective by answering the question, ‘Who do I want to do what?’ and then writing a promotional brief;

• you know of the need to define success, pick a KPI and then measure it to confirm that success (more of this in Chapter 15);

• the processes of brainstorming, list making and mind maps have been used to enable you to think imaginatively and creatively about promotional solutions (from Chapter 4);

• you have in mind the suppliers you can use and the ways in which they can help you devise and implement an effective promotion (from Chapter 5).

Now it is time to look at the nuts and bolts of implementing a promotion: budget, timing, communication, logistics and legalities. A simple three-stage cycle takes you from initial idea to completed promotion.

Budget

In many cases, particularly if you are working in an agency, the budget is given and you simply have to work within it. Will you be able to achieve all you want within the available budget? Are you sure? If not, go back to the beginning and start again. It is best not to try to cut corners, as it is usually more expensive in the long run.

What, though, if you have the freedom to set the budget? Money for promotions comes from the same budget as money for every other part of the promotional mix, though money for price promotions may be accounted for differently (this is discussed in Chapter 9). There are five ways in which companies set their promotional budgets:

• The figure they spent last year, plus a little bit more for inflation and any expected market growth.

• A fixed percentage of turnover, established over time for the company and industry.

• The same as, or in ratio to, what major competitors spend.

• The amount needed to achieve the defined marketing objectives – that is, what is needed, no more, no less.

• In cost-cutting times, if you have not – through marketing accountability – shown value for money from all your marketing, then expect to be given the same as last year or expect to be cut!

The WKS survey showed that few firms changed their budget year in, year out, so it reduced in real terms and they did not change what they spent it on either. They ignored anything new – the new media, direct marketing, accountability and advertising other than press, TV or posters. IPM exam students do call in to the author to ask how to persuade their boss, usually an account manager, to consider using a promotion, rather than just advertising on its own.

Starting with a blank piece of paper each year is a difficult task and, in practice, companies use one of the first three methods, a combination of them or the last. Promotions can be costed as a separate and specific intervention in the market. The cost of the promotion and the margin it generates can be compared with the margin you would expect to make if you did not use the promotion. In fact, it is wise to declare a marketing budget in two parts: the maintenance element – that which you need to do to just stay in the market and the extra to achieve growth etc. If you have been set a growth sales target, you will then require an additional revenue-generating promotional budget.

There is a simple piece of arithmetic that is basic to a promotion and deals with the relationship between promotional packs, proofs of purchase, opportunities to apply (OTA), redemption rate and cost. In this example, assume you are offering consumers the opportunity to mail in for a free model car on a packaged grocery product. The sequence is as follows:

1 Your first decision is how many labels to print the offer on to. Assume you want the promotion to last for a month. Take a month’s volume, add 10 per cent for extra uptake and you can calculate the number of promotional packs required as being, say, 250,000.

2 Next, you decide how many proofs of purchase you will ask consumers to send in. Set it too low and your regular consumers have no incentive to buy more. Set it too high and your less regular consumers have no chance of participating. A good rule of thumb is to set it at the average level of purchase of the category (not your brand) in the promotional period – in this case, a month. Assume, on this basis, you decide on five proofs of purchase.

3 Now you can calculate the opportunities to apply (OTA). This is the number of promotional packs divided by the proofs of purchase. It is impossible for there to be more redemptions than this. In this case, the OTA is 250,000 ÷ 5 = 50,000.

4 Now you must estimate the likely redemption level. This depends on the attractiveness of the premium, the ratio between proofs of purchase and purchase frequency, the amount of support you give to the offer, the strength of your brand and a host of other factors. Assume, in this case, a six per cent redemption rate. The calculation is then the OTA multiplied by the redemption rate. In this case it is 50,000 × 6 per cent = 3,000.

5 Now you can bring in the cost of providing the model car and receiving and handling applications. In the discussion on handling houses in Chapter 5, it was suggested you ask the cost of handling, etc. Suppose there was an estimate for handling a model car (£1.00) of 80p. The total cost per redemption is thus £1.80.

6 Now you know the cost of this part of the promotion. It is redemptions multiplied by the cost per redemption, in this case 3,000 × £1.80 = £5,400. You can add to this the cost of artwork, special printing and other support for the promotion such as postage and packing the car. Assume this is £5,850, giving a total of £11,250.

Finally, you can express this figure as a cost per promoted pack by dividing it by the number of promoted packs. In this case, it is £11,250 ÷ 250,000 = 4.5p. The figures here are only illustrative to show the calculation and for comparison purposes.

This last is a very useful figure. You can use it to compare the costs of different promotions on a like-for-like basis. You can use it to calculate how many extra packs you need to sell for the promotion to break even. If the cost is too high, you can also use it to go back to your calculations and try to find savings – for example, by asking consumers to contribute to the cost of postage, finding a cheaper model car or increasing the number of proofs of purchase.

If you are running a coupon (see Chapter 9 for details), the same calculation applies. Remember that the OTA is not calculated on the readership of a newspaper but on its circulation. Those with a higher number of readers per copy may have a higher redemption rate, but a coupon can be cut out only once.

You will also need to keep a careful watch on VAT. HM Revenue and Customs produces a series of booklets dealing specifically with promotions, business gifts and retail promotional schemes. They are, of course, subject to change, so you should make sure you have up-to-date copies to hand.

Valassis now offers a handy calculator set out on excel spreadsheets for direct mail, internet self-print at home and door-drop coupons. You just enter the figures in the spreadsheet and it calculates. Ask Valassis for their Coupon Campaign Business Model V10 (see Further Information).

Timing

Sales promotions (a promotion offered in the retail space) are often run to meet short-term market needs. They must also work with the lead times of intermediaries and suppliers. This makes timing a critical issue and one about which there is often conflict. It is important to be clear from the beginning about the following time constraints:

• when the promotion is needed to impact on the consumer;

• how long it will last;

• how that relates to the purchase frequency of your product or service;

• what lead times intermediaries require;

• how long you have for print and merchandise delivery;

• when you need your promotional concepts ready.

The time available at each stage strongly affects what can and cannot be achieved. Managing this can be significantly helped by the use of simple project management charts.

Communication

Every promotion is communicated in or on material of some kind. The options include:

• the wrapping of the product;

• leaflets in or with the product or service;

• leaflets separate from the product or service;

• advertisements in the press or on radio, TV, internet or posters;

• sponsored shows or events;

• posters, stickers and other support material;

• sales aids;

• mailshots;

• mobile marketing (including apps).

At an early stage, you need to identify ballpark costs for what you want to do. You can firm them up later, but you need to know that the promotion is, in principle, affordable. To do this you need to:

• select the appropriate communication media;

• estimate the quantities needed;

• estimate the specifications (colour, weight, frequency and so on);

• estimate artwork, photography and other design requirements, and obtain ballpark costs at first and detailed costs later.

This can involve a great deal of phoning to print, media and other suppliers. A useful short cut is to obtain one of the published guides to print and media prices and base your estimates on that. Another is to keep a file of all promotions that you have costed and cannibalise the prices. Promotion agencies tend to be particularly good and quick at this, as they have a wealth of experience to draw on.

While the nuts and bolts are being developed, time can be spent drafting the words that will be used to communicate the promotion. There are always two parts to the verbal presentation of any promotion: the upfront claim and the technical details, rules, instructions and other essential, but secondary, information.

It is common for agencies to present concepts showing what the printed material and advertisements will look like. This has one major danger: until the copy or scripts are written, it is impossible to know how big the printed material will need to be. Often the concepts are presented and the budgets agreed but later someone has to ask for an increase in budget because the leaflet needs an extra page.

Write the copy or script first, even if only roughly. This will guide the designers and enable them to create a far better visual concept. Experience shows that the tighter the brief given to designers and copywriters, the better the results and the greater control you have over costs.

Use the websites of the IPM and DMA to obtain examples of the wording needed for coupons, etc. The Royal Mail gives updated examples on its website of direct-mailing costs for different sizes of mailings.

Keep the creative approach simple. You have very little time to communicate your concept to the consumer. It is better to have a ‘Win a holiday’ headline than ‘Bloggins summer spectacular’. The first communicates the benefits, the second, nothing to those not directly associated with Bloggins. Remember, too, that research shows ‘Free’ and ‘New’ are key words that trigger the shopper’s subconscious mind to take a second look, as does a ‘£1’ flash.

You’ll also need to consider how the offer will be presented graphically. Whether it is communicated by leaflets, advertisements or in a small space on a pack, some form of graphics is needed. Even if you are doing the promotion yourself, some help will be needed here. It is important to reflect the style and feel of the offer in your graphic design and (if possible) enhance the underlying values of your product or service.

Logistics

Every promotion requires something to be given away – whether it is a prize, a coupon, a free mail-in premium or a charity donation. Having isolated what the offer consists of (win a holiday, send in for a kitchen knife, redeem a 25p coupon), it is possible to do the following:

• draw up a specification for the items involved;

• estimate the quantity needed;

• obtain at least ballpark costs.

Again, it is helpful to go to the sourcing website (Chapter 5) or have reference books to hand to short-cut the process of phoning or writing for samples and prices. Do use the websites for examples – you can quickly get quotes too. You can then turn to the operational characteristics of the promotion – how the promotion will actually work:

• Who will do what?

• Where will items be stored?

• How will they be distributed?

• What resources are needed at each stage?

What comes into this depends very much on the scale of the promotion and on your own resources. For a simple retail promotion, it may be no more complicated than arranging the printing and distribution of POP material. Other promotions can be very much more complicated and can involve marshalling half a dozen different organisations, a dozen types of printed material and offer materials of many kinds.

You’ll need to ask yourself how feasible your promotion is. Be aware that much POP material is never displayed or properly displayed by retailers (The Handbook of Field Marketing by Alison Williams and Roddy Mullin, published by Kogan Page, explains how to overcome this). A brand manager once bought some excellent deckchairs at an extraordinarily good price for use as a dealer loader (these are gifts given to retailers – see Chapter 10). It meant that his dealer loader offer would be far better than usual and far superior to those of his competitors. Unfortunately, he forgot that most of the sales representatives were on the road for three days at a time making 15 calls a day. The brand manager had forgotten to consider how to fit 45 deck chairs into a Ford Escort. However, before you decide it is not feasible, ask yourself how it can be done rather than accept that it cannot. Be positive. Only when every option has proved impossible should you give up. After all, your great idea deserves to see the light of day.

Legalities

The legal and self-regulatory controls on promotions are discussed in Chapter 14, but it is worth discussing the subject briefly here.

It’s best to start with the positive values that exist in your brand and in your relationship with your customers. Creative promotions have their origins in the values of a brand, in a shaft of lateral thinking that captures the imagination and fits the brief like a glove. However, sometimes you can get carried away with enthusiasm.

Ask yourself, does the activity conform to the various codes of practice and the law? If it does not, then the worst thing you can do is to try to bend the promotion to fit. This usually ends up by emasculating the promotion and making it too complicated.

Remember also to check how the activity will reflect on the promoter. Short-term gains that are achieved by an unfulfilled expectation on the part of the consumer will damage the company’s reputation in the longer term. If something looks too good to be true, it probably is: remember how the Hoover flights promotion (see Case study 50) almost killed the company.

A very simple rule to follow is to put yourself in the position of the consumer and think how you would feel about being made this offer. In writing about direct marketing and door-to-door or mailshots, I have always advocated trying it out with a letterbox – especially with other post. Does it look sufficiently different and exciting when it falls to the ground in a pile? If you would be unhappy, then so will your targets. You may also think again of your imaginary village and see how its inhabitants would react. ‘Do unto others as you would be done to’ is as applicable to promotions as to the rest of life. Think highly of consumers – they are neither stupid nor gullible.

A structured process

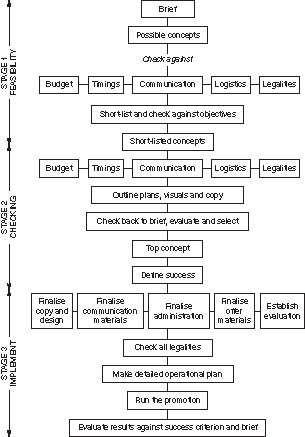

Managing the implementation of a promotion is no easy task. It helps if you divide the work into three stages from brief to implementation, each separated by evaluation and decision phases, and resist the temptation to go straight to the detailed development of the first concept that comes to mind:

• Stage 1: Think through the possible solutions to the promotional brief. Define success. What KPI will you use to measure it? Reserve some budget to measure the KPI.

• Stage 2: Develop your leading concepts in outline form.

• Stage 3: Develop the top concept into an operational plan. Recheck the KPI.

Below, we will look at each of these three stages in turn, focusing on the work to be done at each stage – possible solutions, outline development and detailed development. Keep the stages separate, but remember it is all one process. Think of the stages as a series of loops. Figure 12.3 illustrates the process.

Figure 12.3 From the brief to the result

Stage 1: Possible solutions

Bear in mind the promotional objective and the promotional brief. Define success and set the KPI you propose to use to measure success. List possible concepts. Each concept will be described in a dozen or so words, often with further possibilities in brackets. A concept could be described as ‘Competition – spot the ball (try a variant?) – holiday prize (Tenerife? Florida?) – plus vouchers for everyone who enters (if they cost less than £500)’. Another may be even less specific about mechanics, but focus more on a theme: ‘Win a holiday – competition or free draw – total prize pot £10,000’.

Now you have to apply a rough filter to the ideas you have developed. Figure 12.3 shows how it looks in flow chart form. This stage is the top part of the figure.

In the short-listing phase, you will need to go back to the marketing objective and promotional objective and see whether or not your brilliant idea is likely to achieve the objectives. Keep the promotional brief to hand and remember how you defined success. To continue with the lager example from Chapter 4, will promoting it in tennis clubs really achieve a sufficient increase in sales? If it won’t, you’ll have to start again. Be particularly careful of the promotion that grips the customer, but not the objective. A promotion is there to meet a marketing objective, not simply to engage the customer.

Depending on the brief, you will end up with as few as one or two possible solutions or as many as half a dozen. You can take these forward to outline development. Typically, a promotion agency brings these items together on a ‘concept board’. This is a rough illustration with the key message on it that instantly communicates the offer, backed up by one or two sheets of A4 on which are set out how the promotion will work and what it will cost. If you are doing it yourself, you will still need to see what the offer will look like and note down its key costs and operational characteristics.

Stage 2: Outline development

The task now is to flesh out the details of your short-listed concepts and to establish whether or not they will actually work in practice. This process is shown in the middle part of Figure 12.3.

Working up the short-listed concepts is not a matter of doing different things to the first stage – it is doing the same things in more detail. So, for example, you will work out the detailed print specification and start writing the body copy. This process will narrow down the candidate concepts. You know that the concepts you are left with will work and how they will work. These are the concepts to choose from. Now is the time to go back to the promotional brief and critically examine each candidate concept against it. Which really fits best? Which has strengths in one area but loses out in another? Which really meets the promotional objective? Which gives the most added value? And which will turn on your target audience the most?

For a big promotion, formal research is often advisable at this point, but research of some kind can be done for every promotion – simply by asking people you know. Friends, colleagues at work, customers – all can be subjected to what is often (unfairly) called ‘the idiot test’. Simply line up the concept boards, ask them to think themselves into the position of the target audience and rate your concepts on three criteria: clarity, attractiveness and accessibility.

It is surprising (and mortifying) how often your favourite concept will leave other people cold. You are too close to it to be objective yourself. And even if the concept is clear enough, there will be points where it can be improved and ideas for these tweaks will come from the most unlikely sources.

At the end of this process, you are in a position to select the top concept. If it fits the brief like a glove and excites the people you show it to, you know you have a winner on your hands. At the very least, you will have a sound, workable promotion that meets the brief you set. Now it must be turned into physical items, such as leaflets, posters and the like.

Stage 3: Operational plan

This stage takes your top concept through to implementation. The elements of this stage are shown in the lower part of Figure 12.3.

This is the stage at which to check the criterion for success, set the KPI to measure and the budget to carry out the measurement and finalise and check all the secondary copy for the promotion – entry instructions, rules, descriptions of the prizes and so forth. It is imperative to follow the Code of Sales Promotion Practice in doing so. Use the websites to check this. The rough visual also needs to be turned into artwork for all the various printed items for the promotion. Outside help will almost always be needed here.

The materials necessary for the promotion can now be obtained. It is normally possible at this stage to beat the ballpark prices obtained earlier because you now have a firm intention to proceed, so it is worth shopping around for better prices.

It is particularly important to pay attention to the operational plan. Many promotions fail despite excellent concepts, superb designs and exciting offers because a simple error has been made in the administration system. It is vital to go through this in the finest detail and to ensure that every aspect of delivery, handling and distribution is fully organised. Handling houses, and other suppliers described in Chapter 5, are crucial at this stage. A detailed operational plan sets out exactly what will happen when, by whom and how. A really tight plan leaves no room for error or misunderstanding and saves a great deal of time in the long run. After a while, the framework of a good promotional operational plan for your own company will become established, and so the process of drawing it up will become quicker as time goes on.

The operational plan must include contracts with third parties. They are of particular importance where the operation of a promotion depends critically on another company performing functions delegated to it. Contracts should always be drawn up for the following:

1 Joint promotions. These are a disaster if the relationship turns sour, and one of the most effective ways of promoting if the relationship flourishes. A contract not only establishes the ground rules, but also obliges each party to think through all the eventualities before committing to a promotion.

2 Agency relationships. A relationship with a promotion agency should always be governed by a contract setting out mutual responsibilities.

3 Premium supply. Contracts beyond normal purchasing conditions are not generally necessary if you are making a one-off purchase of premium items. They are necessary if, for example, you are seeking to call off items for a promotion in the future or if a special item is being made.

4 Others. Contracts are advisable with handling houses, auxiliary sales forces, telesales operators and other specialists.

The formats of contracts vary enormously. Some companies write special contracts, others use long and complicated standard contracts. Many find that an exchange of letters backed by a set of standard conditions of trade provides the best balance. As promotional redemption rates are not always predictable, it is important to allow for changes in requirements in your contracts and to know on what basis the cost of any extra work is calculated.

Finally, you should establish responsibility for the marketing accountability accounting and evaluation systems. You decided what success would be, you set a KPI and you need to make someone responsible for measuring the KPI. When you have the KPI results collected you will be able to evaluate the actual results against your definition of success. It is too late to think about how to evaluate a promotion after it has been run, when you have missed the opportunity to record much of the information. The time to do this is beforehand. There are various key measures that will flow from your objective (discussed further in Chapter 9).

Now run it

Now it is time to run the promotion. A promotion set up along the lines of the processes described here should run without a hitch, but it is always important to monitor its progress and be prepared to react to unforeseen developments. Redemption rates, in particular, should always be monitored closely against the expected rate. Remember, too, that a promotion ends when you have analysed all the available information to establish whether or not it achieved the objective set and your definition of success and to draw out whatever lessons can be learnt.

Case studies

The four case studies in this chapter have been chosen because they illustrate the selection of promotional objectives and because of the way they make the link between business objectives and promotional mechanics.

Every promotion in this book has something to say about the link between marketing objectives, promotional objectives and mechanics.

Case study 74 – Hay Fever Survival by the Blue-Chip Marketing Consultancy for Kimberly-Clark

This covers 7 years of the promotion, run from 1991 by the manufacturer of the leading brand of tissues. It is a rare story of consistent promotional development.

The original brief was simple and focused: to build a strategic platform to sell Kleenex tissues in the summer. Why hay fever? About 10 per cent of the population suffer from it, concentrated in particular geographical areas and on particular days when the pollen count is high. They are heavy users of tissues, but responsible for a small percentage of volume. Focusing on hay fever gave Kleenex tissues a promotional theme in the summer that used the demands of extreme product usage as a metaphor for best quality, softness and strength. While focusing on the hay fever sufferer, the offer had to appeal to all buyers of tissues.

The original promotional offer was for a free hay fever ‘survival kit’ in return for three proofs of purchase. It consisted of a toiletries bag containing an Optrex eye-mask, Merethol Lozenge pack, travel pack of Kleenex tissues, money-off coupons for sunglasses and a room ioniser, and a 20-page hay fever guide from the National Pollen and Hay Fever Bureau. It was a partnership promotion, in which Optrex and Merethol provided their samples free. Why should they do so? Because Kleenex tissues could sample the hay fever sufferer in a way that no other brand could. Run on 900,000 packs, the promotion produced a 7.7 per cent response.

The next promotion bore a strong similarity to the original promotion, though now running on nearly 5 million packs and developed to include ‘natural remedies’. In return for five proofs of purchase and 50p towards postage, the consumer received a toiletries bag containing an Optrex eye-mask, tube of Halls Mentho-Lyptus, travel pack of Kleenex tissues and a hay fever guide from the renamed National Pollen Centre.

What happened in the next 5 years? It’s a fascinating story of how promotions adapt to new needs and new opportunities – and how they can also lose their way.

In the first year, the recession forced a drop in the promotional budget. The toiletries bag was now unaffordable, and consumers were asked for 40p as a contribution towards postage. The contents remained the same but, to pick up on interest in that year in Europe, the guide became a European hay fever guide, with handy tips for travellers. There was also a new opportunity. Vauxhall had just launched the first family-priced car with a pollen filter, the Corsa. One was made available as the prize in a free draw. Despite this addition, the offer was objectively less valuable to the consumer than in the original promotion, and redemptions dropped to 3.9 per cent.

Kleenex tissues then tried a new tack – a two-level offer. A new hay fever guide was available for one proof of purchase, and a set of samples for three proofs of purchase and 40p. A strong profile was given to an 0891 (premium rate phone line) ‘pollen line’. The creative treatment also changed. From focusing on ‘hay fever survival’, it now focused on ‘those critical days’ when the pollen count is at its highest. Extended to 4 million packs, the two-level offer was not a success. Redemption dropped to 0.3 per cent for the guide only, and 1.3 per cent for the sample kit.

This caused a rethink for the next year’s promotion. Providing a clear and uncomplicated incentive to trial and repeat purchase became the priority. The 0891 number was dropped in favour of a link with the Daily Mail and Classic FM. The sample pack was slimmed to a new hay fever guide and three samples – Kleenex tissues, Optrex and Strepsils. The central offer was a high-quality AM/FM radio consumers could use to find out the pollen count. It could all be obtained for £3.50 plus five proofs of purchase. The ‘hay fever survival’ theme was prominently back. Response increased to 1.7 per cent, despite the higher requirement made on the consumer for both proofs of purchase and cash contribution.

This was not to last. The focus of the offer changed significantly. The central offer was a ‘pollen-filter’ Vauxhall Corsa to be won in a free draw each week for the ten weeks of the ‘pollen season’. The runners-up – 10,000 of them – received hay fever survival kits that included a new hay fever guide. Redemptions were 9.5 per cent.

Ten ‘hay fever-free’ family holidays then replaced the Vauxhalls as the prizes in the free draw, with 6.4 per cent redemption. Unlike in previous years, they included the option of ‘plain paper’ entries and did not require even one proof of purchase.

The wheel turned full circle. The promotion was a virtual remake of 1991, with the addition of strongly featured pollen count information in partnership with the Daily Express and Talk Radio. In this 7-year period, Kleenex share of the branded tissue sector has increased from 50 per cent in 1990 to over 70 per cent in 1996, recording increases every year. Its share of the total market increased to over 40 per cent, attracting extra volume from the 50 per cent of consumers who buy both Kleenex tissues and own-label tissues. Promotion has been one of the key marketing weapons throughout this period and must take a major share of the credit.

Operating on-pack, at point of sale, in the media and with third-party endorsers, it has been a thoroughly integrated promotion. Three factors that stand out in this case study undoubtedly helped: the ability to seize new opportunities such as the launch of the Corsa, the proactive relationship with third parties and the close partnership that Kimberly-Clark has formed with the Blue-Chip Marketing Consultancy. It is the UK’s most acclaimed promotion, winning 11 awards, including an ISP Grand Prix and two on a European level.

What changed and what remained constant in the business objectives behind the ‘Hay Fever Survival’ promotions?

Case study 75 – Zantac 75 by Promotional Campaigns Group

Zantac 75 is a remedy for indigestion and heartburn that was launched in 1994 as an over-the-counter (OTC) version of Zantac, the leading prescription medicine. OTC products are medicines that the consumer buys without a prescription, but not on open shelves. The consumer must ask the pharmacist or pharmacy assistant for them, and will often seek his or her advice. Just think through the people involved, following the Figure 12.2 example.

The difficulty Zantac 75 faced was that the product story was complicated. There were seven training manuals for sales reps to read. Unless reps could talk knowledgeably about the product to pharmacists, there was little chance that they would stock or display it, let alone recommend it to consumers. The promotional objective was simple: to ensure that reps were fully educated about Zantac 75 and able to present it effectively to pharmacists.

The solution was an e-mail game that took the theme of Zantac 75’s world leadership in the prescription market. Each rep chose a world leader from a list that included Margaret Thatcher, Boris Yeltsin and Nelson Mandela. This identity was flashed on the rep’s laptop computer every day. Every three days, a new episode of an amusing story about world leaders was sent by e-mail. The script was tailored to each rep’s personality to increase involvement. Product learning was reinforced by questions from an imaginary Home Office, Treasury and Foreign Office.

All the reps participated, scoring an average of 90 per cent correct answers. Within 4 months, Zantac 75 had achieved 100 per cent distribution in independent pharmacists, and within 6 months it was the second most recommended brand of indigestion remedy in the UK.

Driving people into learning is hard work for learner and teacher alike. This promotion used a novel technique to make learning fun. It focused on product knowledge as the critical issue for the brand at that point in its life, and delivered the goods. Pensions companies that are counting the cost of poorly trained reps could well learn from this case.

How had the manufacturers of Zantac 75 answered the ‘Who do I want to do what?’ question, and with what result?

How many categories of intermediary were involved in selling Zantac 75 to the consumer, and how did the promotion relate to their different needs?

Case study 76 – ‘Measure Up’ message for Diabetes UK sponsored by Shredded Wheat

Most of us equate waist measurement with the size of clothes we buy. Diabetes UK highlighted it as one of the risk factors associated with diabetes, together with the warning that one in ten of us will become diabetic. A highly visible bright pink roadshow vehicle visited eight UK city centres. Visitors could drop in for information from medical experts and nutritionists as well as undergoing a blood glucose level test. The exterior of the vehicle carried heavy ‘Measure Up’ branding and hard-hitting messages. Each visitor received a ‘goodie-bag’ with Diabetes UK literature and a sample pack of Shredded Wheat from the roadshow sponsor. The campaign was supported with mailings to healthcare professionals, posters and national press ads.

Awareness of diabetes and Diabetes UK was raised by 50 per cent among the target market during the campaign. After the campaign, 150,000 adults visited their GP for a diabetes test, and the combination of media and face-to-face activity achieved a reach of 33 million. This was a cause-related ISP 2007 gold award winner.

Schools were offered two entirely unconnected opportunities to build their collection of musical instruments. Both picked up on research evidence that schools were short of musical instruments and valued them highly. The promotions from Jacob’s Club and the Co-op offer a contrast in objectives and execution round an identical theme.

Jacob’s Club is the third biggest chocolate biscuit brand, with a 6 per cent market share. It is constantly faced with the challenge of larger brands and new entrants into a highly competitive market. Half its volume is purchased for use in lunchboxes.

Its promotional objectives included achieving a sales uplift of 25 per cent, increasing consumption in lunchboxes and reinforcing its family and caring image. The promotion, devised by Clarke Hooper and printed on 150 million packs, invited consumers to take the wrappers to school. The school could in turn redeem them for musical instruments. Direct mail to 25,500 schools resulted in 30 per cent of them registering. Telephone follow-up increased that to 90 per cent.

Nearly 14,000 schools claimed a total of 36,000 instruments worth over £800,000 at retail price. The entry point was low – a descant recorder worth £6.99 could be obtained for 295 wrappers, a spend of £29. Brand volume rose by 52 per cent during the promotional period, and household penetration rose by two-thirds.

The Continuity Company’s promotion for Co-op was targeted at 16,000 schools near to the 1,300 participating Co-op stores. Recruitment was by direct mail, followed up by postal reminders. A total of 9,000 schools registered. The mail-out to schools included posters, wall charts and A5 leaflets to send home with each child. Co-op shoppers obtained one voucher with every £10 spent, which schools could redeem for instruments. There was a low starting point – just 35 vouchers entitled a school to a £5.99 descant recorder, representing an expenditure of £350. The Co-op promotion stabilised sales in the period up to Christmas. It also resulted in 190,000 instruments being claimed by schools.

Schools welcomed both promotions – 91 per cent told Jacob’s that they would participate again, and 98 per cent said the same to the Co-op. Both have a number of factors in common: not being market leaders; appealing to families; having a broadly sharing, community image; and facing intense market competition. It is not surprising that their promotional analysis led them to very similar promotions. Both succeeded against their objectives, and both attracted considerable PR coverage.

There are a number of details that are different, however:

• Jacob’s backed the promotion with TV, the Co-op with press.

• Jacob’s used telephone follow-up, which the Co-op did not.

• Jacob’s enlisted the support of the Music Industries Association, while the Co-op used the endorsement of celebrities like Richard Baker and Phil Collins.

• Basically similar descant recorders required £29 to be spent on Jacob’s Club or £350 in Co-op stores.

Does it matter that these very similar promotions ran at the same time? It would have done if KitKat and Club or the Co-op and Asda had run them, but Club and the Co-op are in different sectors. Analysis of similar promotional objectives can lead to similar solutions. The executional differences give a good example of how the way in which a promotion is carried out gives the promoter a range of options once the main approach has been decided.

To what extent were the objectives and business context of Jacob’s Bakery and Co-op different in the ‘Music for Schools’ promotions?

Summary

Setting out the brief clearly and concisely is an essential first stage in devising a promotion. If the brief is not clear, your promotion will be built on sand. It is easy to miss out this stage if you are devising a promotion yourself, but it is a mistake. A good brief saves time, and well-defined objectives make the selection of mechanics straightforward.

The objectives and mechanics identified in this chapter do not constitute a rigid grid, but they provide a good checklist for you to develop and apply. The rest of the brief will help you to organise the promotion in detail.

Implementing a promotion is a logical three-stage looping process. It is a mistake to try to take short cuts. The process can take a short time – just a week if necessary. The benefit of a system is that it takes you logically through all the stages and avoids costly mistakes. Following the system will not guarantee world-beating promotions, but it will ensure practical, workable promotions that achieve your objectives. It is vitally important to attend to issues defining success and setting the means of measurement (the KPI), budget, timing, communication, logistics and legalities in turning a promotional idea into a fully fledged promotion and then to evaluate it so that lessons can be learnt before repeating the cycle. Look again at Figure 12.3 as a reminder.

Self-study questions

Use the following questions to identify what it is in particular that the four case studies illuminate. From the evidence presented, how successful were the promotions in achieving their objectives? What other mechanics could the agencies have considered to achieve those objectives?

1 How can a promotion be planned strategically?

2 What are the main points to include in a promotional brief?

3 What sorts of promotion are best for encouraging trial?

4 What sorts of promotion are best for encouraging repeat purchase?

5 What are the pros and cons of delayed and immediate promotions?

6 What are the different ways in which you can set a budget for a promotion?

7 If you offer a premium with three proofs of purchase on 150,000 packs, how many opportunities to apply will there be?

8 What are some of the main issues to watch in contracts for promotional supply.