Chapter 2

Structured Real Estate Financing

In a similar manner to project finance operations, structured real estate finance involves the funding of a transaction in which the bank accepts the cash flows generated, or which may be generated, from the property financed as collateral for the repayment of the debt.1

The due diligence carried out by the bank when granting these loans involves an assessment of the economic and financial equilibrium of a specific real estate asset or project, which will preferably be legally and economically independent of the other initiatives carried out by the sponsors which conclude the transactions. The real estate project to be financed will generally be implemented by its sponsors by creating a special purpose vehicle (SPV) which permits the investment to be separated in economic and legal terms.

A real estate project is assessed by the banks and its sponsors principally with reference to its capacity to generate revenues from the lease and/or sale (also partial) of the properties financed. The cash flows associated with the real estate transaction provide the source for servicing the debt as well as paying a return on the equity capital invested by the sponsors.

The guarantees may be real (e.g. pledge on SPV shares, mortgage on the property) or contractual (e.g. assignment of receivables as collateral, contractual covenants), although it is the contractual guarantees which actually assure the banks that the cash flows generated by the real estate asset will be the primary source for servicing the debt. These loans may be of two different kinds.

- Non-recourse or without recourse, when no right of recourse is specified (for example through the issue of guarantees or comfort letters) against the sponsors of the project or third parties. The capacity of the real estate project to generate sufficient cash flows (which are only potential in cases involving development projects) in order to repay the debt, along with a contractual structure that guarantees the success of the real estate investment and the repayment of the underlying debt, are the main elements to be assessed by the lending banks.

- Limited recourse, that is with recourse limited to situations in which rights of recourse are provided against the sponsors or third parties upon occurrence of situations specified in advance under contract. For example, in a development project where construction costs are only partially financed by the bank, the latter will demand from the sponsors a commitment or a guarantee to inject into the project both any capital shortfall arising during the construction phase, as well as funds to cover unexpected costs.

Obviously, the bank will also carry out a financial credit check for non-recourse loans in order to verify the solvency of the shareholders and/or of the financial group of the borrowing company. The aim is to avoid any default by the transaction's sponsors affecting, even indirectly, the real estate project financed as well as to assess the resoluteness and reliability of all parties involved in the transaction.

The cash flows result from rent (either property leases or going concern leases), whilst in development projects they will be generated from the sale (or lease) of the individual units when construction work has been completed.

Debt financing is generally available for all types of real estate, provided that they can generate cash flows, both actual (for existing income producing properties) or expected (for development projects). Accordingly, the following properties, existing or to be developed, will be eligible to be financed:

- offices;

- high street retail/shopping centres/retail parks/factory outlets;

- entertainment centres/theme parks;

- multiplexes;

- hotels;

- logistic warehouses and industrial;

- retirement homes;

- residential portfolios (to rent and/or to sell).

The loan may be intended to support construction costs or to pay the acquisition price. In the former case, it will be necessary to provide a precise estimate of the costs of the project and of the cash flows which the property may generate once completed: the granting of the loan may also be conditional upon the sale of units successfully sold (particularly in case of residential development projects). In the latter case, it will be necessary to pay particular attention to the relevant clauses in the lease agreements.

The capital structure of a real estate project may be made up of three parts:

- equity (shares and shareholder loans);

- debt capital;

- hybrid financing (mezzanine finance and preferred equity).

The debt amount financed will mainly depend on three elements:

- the reliability of the borrower;

- the transaction for which the loan is intended and its operational risk;

- any guarantees provided.

This amount may be granted as one single credit line, although alternatively secondary credit lines may also be granted, such as for example a specifically dedicated VAT line.

In all cases, the equity that is to be injected by the sponsor cannot usually be less than 20–30% of the overall cost of the property. In development projects, this equity level often corresponds to the acquisition cost of the area to be developed. Since lower equity percentages will entail higher leveraging and higher risks for the bank, credit lines exceeding 70–80% of the construction cost (also defined as mezzanine finance) come with significantly higher costs.

2.1 Bank roles

Sometimes there might be the need to arrange a syndicated loan,2 which means involving several different lenders in providing parts of the same loan. This might happen when the debt amount is particularly large and therefore too much to be provided by a single lender or above its risk exposure levels. In order to assemble a multibank lending syndicate, a bank will receive a mandate as syndicate manager from the borrower. After the agreement with all the participating banks has been reached, the syndicate manager is usually appointed as the agent bank,3 i.e. the bank which manages the relations with the borrower for the full term of the loan (in particular, monitoring compliance with covenants, collection of instalments, reports to oversight authorities and recovery actions). In particular the agent bank is responsible for notifying other banks of advances or drawdowns by the borrower and changes in interest rate.

When determining the role and responsibility of the agent bank an interbank agreement is concluded in which, inter alia, the agent bank is charged with carrying out all activities concerning the conclusion of agreements relating to the credit facilities, drawdown and the administration of those facilities, as well as carrying out (according to a mandate which may vary in scope) procedural, preventive, or enforcement measures against the borrower or any other guarantors or obligors in order to protect the rights created under the loan agreement.

2.2 Bank loan contractual forms

Different contractual forms may be used in order to finance a real estate transaction, provided that such contracts are appropriate for securing the financial resources from the value of the collateralized property.

Bank loans may come in various forms and are the funds mainly used by companies in order to obtain part of the financial resources necessary to cover their needs. These loans may be classified into two groups.

- Bank account overdraft facilities, where amounts exceeding those deposited may be withdrawn, thus giving rise to account overdrafts (negative balances for the borrower and positive balances for the bank). These forms are flexible in nature because they make it possible to switch between withdrawals and repayments. They may be subdivided into unsecured overdrafts, secured overdrafts, documentary overdrafts, credit lines, and bank account advances on stocks or goods.

- Fixed maturity loans – such loans are disbursed in one or more predetermined instalments and must be repaid at specific maturity dates.

The granting of a revolving secured credit line is the most flexible form of financing for real estate, especially for development/refurbishment projects. The bank grants access to credit up to a maximum limit, which may be used according to the borrower's requirements. This credit line is generally granted in order to finance a specific transaction. The borrower undertakes to redeem the original credit line through full or partial repayments along with the payment of the accrued interests, and may use the cash made available to it according to its own requirements through one or more withdrawals returning the principal with subsequent repayments. The borrower may also borrow back any part of the facility which has been repaid.

2.3 Loans for development projects

Various contractual techniques may be used in order to finance development projects based on the work in progress (WIP). An initial conditional loan agreement specifies the term of the loan and the duration of the initial pre-amortization period during which construction work is to be carried out. Subsequently, individual loan instalments will be disbursed during the pre-amortization stage (namely, the stage during which interest only is paid) initially agreed to. Consequently, all instalments will have the same amortization period, although they may have a different pre-amortization period. A maximum time limit for the repayment of the loan is agreed which may also be amended upon disbursement (as well as the agreed interest rate, which may also be amended). Building construction will subsequently be financed by preliminary disbursements to finance development costs. Upon conclusion of construction works, the definitive loan agreement will be concluded, which will regulate the amortization system (e.g. capital repayments) for the sums financed, consequently determining the interest rate, the frequency of repayments, and the definitive terms of the loan.

2.4 Parts and stages of a structured loan

A structured real estate loan comprises various stages. In order to ensure clarity of explanation, these will be first listed in logical sequence according to the order in which they occur; subsequently their salient points will be described:

- initial meeting between the bank (lender) and the client (borrower) in order to analyse the real estate project and the related financial requirements (see paragraph 2.4.1);

- technical appraisal and feasibility analysis of the real estate project:

- analysis of expected costs and revenues;

- market and catchment area studies;

- analysis of operating income and definition of the financial plan;

- estimate of open market value and mortgage lending value of the property (see paragraphs 2.4.2 and 2.4.3);

- financial due diligence or solvency analysis of the parties involved:

- borrowing company and group;

- building company;

- buyer;

- tenants;

- legal due diligence, during which the contract and related guarantees are prepared (see paragraph 2.4.5);

- tax due diligence, during which the tax law aspects of the loan agreement and the implications of the new loan and the related guarantees on the borrower's fiscal position are ascertained;

- identification of the risk mitigation instruments identified during the creditworthiness, legal and technical analysis, and the resulting finalization of:

- security package;

- insurance policies;

- hedging of interest rate risk;

- contractual covenants;

- identification of the transaction's credit risk in accordance with the various approaches contemplated under the Basel Accords;

- loan pricing, also on the basis of the results of the credit risk assessment;

- issue of an offer to the borrower (term sheet, see paragraph 2.4.1);

- negotiation of the terms and conditions proposed in the term sheet and acceptance;

- continuation of the review stage: drafting and negotiation of the loan agreement and of the security package;

- conclusion of the agreement, issue of guarantees and insurance policies;

- monitoring of the loan involving a control of guarantees and contractual covenants;

- syndication or securitization of the loan, if appropriate.

2.4.1 Analysis of the Transaction and Term Sheet

Generally speaking, the information exchanged between the bank and the borrower during the initial stages of negotiations will contain the following information:

- a description of the project's sponsors;

- an illustration of the structure of the company applying for the loan;

- the project business plan, setting out in particular the deadlines for the various project stages along with economic and financial projections, including pro forma accounts, cost forecasts, the project's capital structure, and the cash flows generated through it.

In some cases, especially where the sponsor is assisted by a financial advisor, an information memorandum will be presented. This is a single document setting out the details of the real estate project to be financed along with the project's sponsors and a working proposal for its capital structure. In other cases, especially where it is necessary to involve more than one bank in the project, the sponsor will ask the bank itself to draw up this document in order to carry out a preliminary review of the bankability of the project.

This stage is extremely important, since it is vital that the project is presented in such a way that enables the bank to understand the characteristics of the real estate project in terms of revenues, costs, cash flows, and risks. This will make it possible to verify whether the underlying assumptions presented by the prospective borrower are tenable. In other words, when disbursing a structured loan, the bank will carry out an analysis which is very similar to that carried out by an equity investor when investing in a real estate project.

During the first meeting with the bank, the borrower will generally present the structure of the transaction and the amount of the loan requested. He may also ask the bank to draw up a document before a particular date setting out the main terms and conditions of the loan with a view to initiating formal negotiations. This document is referred to as the “term sheet” and it is used by the parties in order to conduct negotiations on the main terms and conditions of the loan. It is updated when the real estate project is finalized and during the loan negotiations. Essentially, this document summarizes all of the terms and conditions, the parties involved, the contracts to be signed and the guarantees to be provided, as well as the deadlines for concluding the transaction. The document also specifies:

- the parties which will sign the subsequent loan agreement and their roles;

- the amount and term of the loan; if the amount is not approved in advance the amount is to be capped at the lowest of either:

- specific amount;

- specific max % of LTV and/or min ICR and/or min DSCR;4

- specific % of the purchase price/construction costs (loan to cost);

- the purpose of the loan;

- the property description;

- the forms and procedures regulating the drawdown and the repayment of the loan;

- the determination of the applicable interest rates, margin, and fees that will be paid to the bank arranging the loan (also called the arranger) and/or to the other participating banks when a pool financing is organized;

- the interest hedge (in case of variable interest);

- the repayment;

- the interest period;

- the security package to be issued;

- the main rights and obligations of the parties, and any special terms, condition precedent, and conditions required by the concession or the nature of the construction work planned;

- the covenants which will be required upon conclusion of the agreement;

- the temporary limitation of the term sheet;

- the representations and warranties;

- events of default;

- any other terms and conditions which must be complied with in order to obtain the approval of the bank and the drawdown of the loan;

- choice of law/jurisdiction.

Due to its characteristics and to the high level of detail in the conditions which the term sheet may contain, the problem arises as to whether it amounts to a genuine preliminary agreement or, instead, to a non-contractual undertaking, namely a pre-contractual act intended to “crystallize” the state of negotiations or the preliminary agreements reached, thereby facilitating the conclusion of the overall agreement. The settled view is that the term sheet is a pre-contractual act which is as such capable of establishing a pre-contractual liability and an obligation to compensate damage as protection for the legitimate expectation created for the counterparty.

In fact, although the contents of the term sheet may differ significantly and be more or less binding depending upon the level of agreement that has been reached, the parties themselves usually wish to specify that the term sheet does not have the status of a preliminary agreement by including explicit clauses to that effect. The efficacy of the term sheet is generally conditional upon the subsequent approval of the conditions contained in it by the credit committee of the parties involved. Generally speaking, the bank will include a clause at the end of the term sheet stating that.

“The term sheet constitutes only a draft outline of the terms and conditions on which the bank would be prepared to consider making available a facility and is in no way to be construed as an offer or commitment to provide finance. Any decision regarding the provision of finance requires the approval of the lender's credit committee.

In this way (no binding offer) the term sheet is not considered (in most jurisdictions) an offer which already leads to a requirement to allocate equity on the side of the lender.

The above applies unless the borrower requests a binding commitment, that is an irrevocable proposal corresponding to a binding commitment by the bank (which is generally requested when the loan has been negotiated with various banks in competition with one another, following a kind of tender procedure conducted by the project's sponsor). In such cases the bank will have to take a specific decision to authorize the signature of the term sheet.

The term sheet may be drawn up during different stages of the loan negotiations:

- during a preliminary stage, if the borrower requests an offer from more than one bank:

- in this case the borrower will attend the first meeting with the bank with an information memorandum containing a detailed analysis of the real estate project and its financial requirements;

- interested banks will formulate their offer before a predetermined date on the basis of the data contained in the information memorandum, specifying that the subsequent approval of the loan will be conditional, inter alia, on the verification of the accuracy and validity of the information contained in the memorandum, which will be carried out by the bank's analysis team;

- the term sheet will be signed by the borrower and the bank which has made the best overall offer;

- during an advanced stage of negotiations: in this case, the bank may request the costs of the due diligence to be paid up-front on a preliminary basis, regardless of whether it actually decides to grant the loan.

Though it does facilitate the parties' negotiations, the signature of the term sheet is not essential in order to conclude a financing agreement.

2.4.2 Real Estate Valuation

The valuation phase is mainly intended to estimate the value of the real estate asset which will be provided as collateral. Estimating the value of properties involves ascertaining its value as expressed in monetary terms, in other words pricing the utility of an economic asset. Banks will generally ask an external surveyor to value the real estate asset, determining the Open Market Value (OMV) and the Mortgage Lending Value (MLV).

OMV is the basis of value supported by RICS Red Book5 and it is defined as

“the estimated amount for which an asset or liability should exchange on the valuation date between a willing buyer and a willing seller in an arm's-length transaction after proper marketing wherein the parties had each acted knowledgeably, prudently and without compulsion”.

MLV in contrast, according to TEGoVA,6 is

“the value of property as determined by a prudent assessment of the future marketability of the property taking into account long-term sustainable aspects of the property, normal and local market conditions, the current use and alternative appropriate uses of the property. Speculative elements shall not be taken into account in the assessment of the Mortgage Lending Value.”

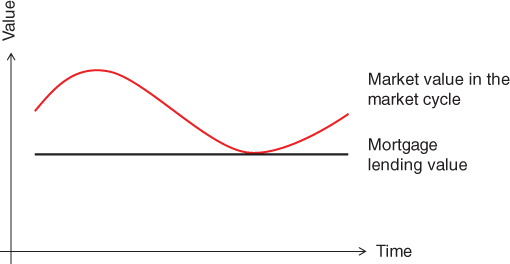

Despite cross-border mortgage lending and the European Mortgage Lending Value (EMLV) of the European Mortgage Federation, only the definition is consistent. If one compares the definitions and the concepts of the OMV and the MLV, the latter is in many respects very similar to the former. However, the MLV as a “long-lasting/sustainable” value introduces additional parameters to smooth market trends. This is made by adaptation of the rental income to a stable obtainable rent level, adjustment of the capitalization rates to the long-term development of the market and customization of the administration and management costs.

MLV may be used by the financial services industry in the activity of lending secured by real estate. The MLV provides a long-term sustainable value limit, which guides internal banking decisions in the credit decision process (e.g. loan-to-value, amortization structure, loan duration) or in risk management.

MLV facilitates the assessment of whether a mortgaged property provides sufficient collateral to secure a loan over a long period. Given that MLV7 is intended to estimate property value for a long period of time, it cannot be grouped together with other valuation approaches used to estimate the OMV on a fixed date.

Additionally, MLV can be used as a risk management instrument in a number of ways in the context of:

- capital requirements for credit institutions as detailed in the Basel Accords;

- funding of mortgage loans through covered bonds secured by real estate as the cover assets;

- the development of capital market products converting real estate and real estate collateral into tradable assets (e.g. mortgage-backed securities8).

The concept of MLV is defined in detail by legislation, directives, and additional country specific regulations.

Regarding the technical transposition of the definition mentioned above, the long-term validity of MLV requires compliance with a certain number of steps aimed at eliminating short-term market volatility or temporary market trends. The valuer must address the following key issues when determining the MLV of a property:

- The future marketability and saleability of the property has to be assessed carefully and prudently. The underlying time perspective goes beyond the short-term market and covers a long-term period.

- As a principle, the long-term sustainable aspects of the property such as the quality of the location and construction must be taken into account.

- As far as the sustainable yield to be applied is concerned, the rental income must be calculated based on past and current long-term market trends. Any uncertain elements of possible future yield variations should not be taken into account.

- The application of capitalization rates is also based on long-term market trends and excludes all short-term expectations regarding the return on investment.

- The valuer must apply minimum depreciation rates for administration costs and capitalization of rents.

- If the MLV is derived using comparison values or depreciated replacement costs, the sustainability of the comparative values needs to be taken into account through the application of appropriate discounts where necessary.

- The MLV is generally based on the current use of the property. The MLV shall only be calculated on the basis of a better alternative use, under certain circumstances, e.g. if there is a proven intention to renovate or change the use of the property.

- Further requirements, for example with respect to compliance with national standards, transparency, content, and comprehensibility of the valuation, complement the legal framework for the calculation of MLV.

There are important differences between OMV and MLV. The OMV is internationally recognized for the assessment of the value of a property at a given moment in time. It estimates the price that could be obtained for a property at the date of valuation, notwithstanding that this value could alter very rapidly and no longer be up-to-date. In contrast, the purpose of MLV is to provide a long-term sustainable value, which evaluates the suitability of a property as a security for a mortgage loan independently from future market fluctuations and on a more stable basis. It provides a figure, usually below OMV and therefore able to absorb short-term market fluctuations whilst at the same time accurately reflecting the underlying long-term trend in the market.

Figure 2.1 shows that the MLV does not pursue the market cycle. It stands out from the varying OMV as a stable line. The MLV in stable markets will hardly differ from the OMV.

Figure 2.1 MLV and OMV

2.4.3 Basics of Property Appraisal

Properties may be valued according to various techniques which can be classified under three main approaches (Comparison, Cost, and Income methodologies), the application of which may involve different criteria.9

- Comparison methodologies:

- Sales Comparison Approach;

- Hedonic models;10

- Cost methodology;

- Income methodologies:

- Direct Capitalization Approach;

- Financial Approach (DCF analysis models).

The different methodologies are based on different principles and they should also be adopted jointly if required by the complexity of the asset to be assessed. In order to establish which approach is to be used in different situations, it is appropriate to compare them briefly with one another.

Under the Sales Comparison Approach, the value of an asset is obtained on the basis of the prices for concluded transactions which may be defined as comparable. This approach is based on the assumption that no rational buyer will be willing to pay a price that is higher than the cost of buying similar assets with the same utility. This assumption is premised on the two fundamental principles of substitution and equilibrium between supply and demand. According to the substitution principle, the value of an asset is the price that should be paid for a perfectly identical asset, whilst according to the equilibrium principle, the price of an asset is directly dependent upon the market (supply and demand) and is therefore the synthesis of the negotiation process.

The Cost Approach is based on the principle that no rational buyer will be willing to buy a property at a price which is higher than the cost of land in the same area plus the cost of building a property with comparable characteristics, after accounting for the loss in value resulting from the ageing of the building. The valuation is therefore based on the measurement of three different elements: the value of the land, the construction costs for a building with similar characteristics, and the adjustment factors that take account of depreciation due to time and obsolescence. A fundamental element within this approach is also the principle of highest and best use, according to which the value of an asset is dependent upon the most probable use which is physically possible, financially feasible, and legally permitted and which offers the highest return on investment.

Finally, the Income methodologies are based not only on the principles of substitution and equilibrium between supply and demand discussed above, but also on the principle of expected future economic benefit, according to which a rational buyer will not be willing to pay a price higher than the present value of the economic benefits which the real estate asset will be capable of generating over its lifetime. These approaches therefore presuppose the determination of an economic benefit (which may be defined as single income or future cash flows) and a time coefficient which takes account of risks inherent in its future economic benefit (capitalization rate or discount rate). The economic benefit of an income producing property is principally the rental income which it may generate net of operating expenses:11 it becomes fundamentally important to identify the level of rental income which the asset is able to generate by analysing a sample of comparable properties on the rental market. It is therefore necessary to analyse rental transactions (rather than transfers of ownership, as occurs under the Comparison methodologies) in order to determine future income flows.

Consequently, the Income methodologies work well when assessing a real estate asset with the following characteristics:

- ownership rights are transferred relatively infrequently (e.g. commercial properties in general such as shopping centres, large office buildings, and logistic parks);

- there is a significant rental market (with a clear distinction between users and owners12

- on the basis of which comparable market rents can be determined;

- the value of the property is not directly dependent upon a physical measure (e.g. price per square metre), but rather upon its capacity to generate income in a manner not strictly related only to its surface area (e.g. shopping centres, hotels, or cinemas).

2.4.3.1 Comparison methodologies

In order to apply the Comparison methodologies it is necessary to have a sufficiently broad historical set of transactions relating to similar assets. By definition, there are never strictly speaking absolutely identical properties since each is unique at the least in terms of its location. However, in practical terms, it is possible to identify the main characteristics which contribute to determining the attractiveness of a property and subsequently its value. The price of a property is always a function of the matching of supply and demand, and will tend to change in line with market trends.

There are also other approaches which fall under this category, including for example the Multiplier Approach. When applied to economic dimensions, multipliers make it possible to determine the value of an asset: nonetheless, the lack of a precise scientific foundation has not limited its development, thanks to the ease and immediacy with which it can be used. Multipliers are generally adopted when determining the value of a given business, rather than a specific real estate asset. As such, the valuation will generally refer to the business's core operations and the characteristics of the property used for it. Cinemas, hotels, golf courses, and fitness centres are just some of the types of assets for which appraisers in practice commonly adopt rules of thumb or market based multipliers. The object of the valuation will therefore be both the property and the business carried on within it (cinema, sports centre, hotel etc.).

The Sales Comparison Approach uses data for comparable properties which have been recently sold in order to determine the value of the property. It is possible to estimate the value of a property on the basis of sale prices for comparable properties by applying adjustments which take account of the specific features of each property. The use of this approach involves three steps:

- selection of comparable properties;

- normalization of the sale prices for comparable properties;

- adjustments.

First and foremost it is important to select properties which are comparable to that which is to be valued. It is therefore necessary to analyse, value, and verify the existence of equivalent properties, and to analyse the prices at which they have been sold, taking account of the elements which impinge upon supply and demand. Properties are compared taking account of their physical characteristics (age, quality, state of maintenance etc.) and location. It is necessary that the characteristics of the properties considered to be comparable are as similar as possible to those of the property to be assessed and that the comparable properties have been sold recently (generally during the last three to six months) at normal market conditions:13 in order to do so at least three or four properties have to be chosen. Prices agreed to in situations resulting from testamentary succession or, normally but not always, from auctions should not be considered since they do not meet the prerequisites of normality.

The second step involves the normalization of the sale price for comparable properties by expressing it in terms of a unit for comparison. For most properties, the unit considered will be the surface area, and hence the calculation will be made with reference to prices per square metre.14 The unit of measurement considered may differ for certain types of properties, depending upon which unit is generating revenues. The unit of measurement is specific for each different type of property,15 and can be extracted from the sample of comparable properties analysed. The final value of the property will be obtained by multiplying the average price for the unit of measurement extracted from comparable transactions by the units of the property to be assessed.

The third and last step involves making adjustments, since no two properties will ever be perfectly identical, for example due to differences in age, state of maintenance, orientation, noise levels, and accessibility. After collecting all information relating to the property and the market, it will be necessary to verify the differences between the information obtained and the individual property to be assessed. For this reason the criterion will never apply to properties which, by their nature, are effectively unique from all points of view. Even for properties which may appear ex ante to be entirely homogeneous, such as each half of a semi-detached house, there may be differences in terms of orientation or noise (for example, one half of the house may be closer to a road). This step is important because it could call into question the choice of comparable properties.

Practitioners often consider that two properties are not comparable if it is necessary to make an adjustment in excess of 20% of the price per unit. If this is the case, it will be necessary to select other properties which are genuinely comparable to the property to be valued or using a different methodology.

2.4.3.2 Cost methodology

The Cost methodology is based on the principle that in most cases an investor will not be willing to pay a price for a property which is higher than the land on which it is built plus the cost of rebuilding it after accounting for any depreciation. The Cost Approach is therefore based on a principle of replacement. In effect, the potential buyer will choose between purchasing an existing property and building a property with the same characteristics on a similar plot of land, taking account of the level of depreciation of the existing property. The sale price may differ from the equilibrium value of the replacement cost if for example some of the characteristics of the property do not match up with what the buyer is looking for or if the buyer wishes to take possession of it immediately. Under the former scenario the value will be lower, whereas in the latter it will be higher.

Calculating the value of a property is equivalent to looking for the correct value of the property originally built to which the value of the land is added. Under this approach, the first cost calculated is that of rebuilding the property as new. Although this can be done in various ways, the most frequently adopted solution is to value the surface area according to a construction cost per square metre or cubic metre. Estimating the value of a building by multiplying the number of square metres by the average construction cost per square metre is a relatively simple operation. However, the various constituent parts of a property do not have the same cost per square metre: in order to avoid excessive distortions, it is possible to break up the total number of square metres into the main elements (garage, residential units, commercial units etc.) and multiply the surface area of each component by the relevant construction cost.16

Once the cost of reconstruction as new has been estimated, in order to determine the value of a property it is appropriate to quantify the property's loss in value compared to the cost of rebuilding as new. This value loss may occur for three main reasons:

- wear and tear;

- functional obsolescence;

- economic obsolescence.

The level of wear and tear of the property depends upon its age, building quality, level of ordinary and extraordinary maintenance, as well as its use. This last factor is for example dependent upon the title according to which the property is used: all other things being equal, an owner-occupied property is indeed usually in better condition than a rented property. The location of a property may also have an impact upon the extent of the level of wear and tear of a property, for example due to factors such as exposure to the elements and pollution.

A loss in value may also be caused by functional obsolescence, that is the failure of the property to meet up with the functional requirements of contemporary buildings, taking account of construction standards and market requirements. There are several examples of this, such as in residential units the number of bathrooms, the presence of a lift, the type of heating, the quality of insulation and soundproofing for the building and in offices the connection to new computer technologies, energy efficiency, and green building standards.17 All of these elements have changed significantly over time, and are also reflected under current legislation. For example, a flat without a lift or with an antiquated heating system will be functionally obsolescent.

Economic obsolescence is perhaps the hardest element to quantify. Here it is necessary to assess whether there is real demand for this type of property or whether there is no demand for some of its characteristics, including even its current intended use. This class should only include factors which can impinge upon the building's value, since any negative impact on the value of the land will already appear in the calculation of its value. A detached house with luxury fittings for which there is no demand illustrates the fact that a property's value does not vary in proportion with its cost. Even though some very luxurious fittings, such as gold-plated taps, have a very high installation cost, they will only be of value if there is demand for this type of characteristic. Hotels located in a region which no longer attracts clients enable one to sketch out the impact of economic obsolescence, which may have an effect on the value of the building without necessarily affecting the value of the land. If it is possible to transform the building in which the hotel is located to other uses, for example residential units, it may be the case that the value of the land does not suffer. On the other hand, the value of the building will fall by the amount necessary in order to adapt it to the new use, in addition to other depreciating factors. In any case, the boundary where the impact on value is to be measured is rather difficult to determine.

The measurement of the degree of depreciation of a property, and hence the corresponding amount, is often relatively difficult, especially if the building is particularly old. The simplest way of measuring depreciation starts from an annual depreciation rate, for example 2% per annum if the lifetime of the building is estimated to be 50 years. It is also possible to consider a non-linear depreciation of the property by choosing lower rates for the initial years during which the property is used and subsequently moving to higher rates. Whilst these solutions are simple, they are often unsatisfactory. In fact, it may be more appropriate to consider the useful life (and hence the rate of depreciation) of each constituent part of a building.

Alternatively, rather than attempting to determine the useful life of an old property or of each constituent part in order to calculate a depreciation coefficient, an estimate may be made of the cost of refurbishment necessary in order to ensure that the property has a useful life that is comparable to a new property. The renovation cost will then be deducted from the cost of reconstruction as new in order to obtain the value of the renovated property.

The estimated value of the property is obtained by adding the value of the land to the corrected construction cost. The value of the land may be determined using information relating to the recent sale of plots located within a comparable area, according to the comparison approach.

When valuing greenfields as well as brownfields (i.e. abandoned buildings), the residual value criterion is often used, which involves identifying the highest and best use of an area, taking account of applicable local planning regulations. From an economic point of view, the best possible use of land is often a property which generates the highest possible rental income or sale prices. This means that first of all one must choose the type of building and the floor area ratio which make it possible to achieve this objective. Secondly, an estimate will be made of the price for which the property may be sold on the market, from which the construction cost for that type of building will be subtracted. The calculation will also have to take account of the profit which the developer wishes to make on the operation, depending upon the time and risk involved as well as the financial costs, thereby obtaining the maximum amount which he will be willing to pay for the land. The application of this methodology may entail the simple summation of costs and revenues, or it may require the discounting of projected cash flows in a manner similar to the approach described in the following paragraph.

2.4.3.3 Income methodologies

Income methodologies seek to determine the value of a property by estimating its capacity to generate economic benefits during its life. The reference to income and cash flows results from the fact that similar methodologies can be and in fact are, applied to all other asset classes.18 These approaches are premised on the fundamental assumption that a rational buyer will not be willing to pay a price which is higher than the present value of the benefits which the asset will be able to produce in its lifetime. This principle, which operates alongside the principles of equilibrium and replacement on which the Comparison Approach and Cost Approach are based, implicitly assumes that this price may not be higher than the cost of buying similar properties with the same level of utility.

The Income methodologies make it possible to express the value of a property as a function of the same factors which determine the value of any asset: projected income and the risk associated with securing this income. In fact, according to these approaches, the value of an asset is dependent upon the future economic benefits which it will be able to produce over the course of its lifetime.

The practice and theory of real estate appraisal are dedicating increasing attention to the Income methodologies, which are well adapted to valuations for properties which generate a regular income flow (consider income producing properties such as offices, shopping centres, hotels etc.). The price of the space (rent) is dependent upon supply and demand, and it is possible to ascertain it from the market analysis of rent levels recently agreed under new leases (annual rent per square metre or square foot).

The value also depends upon the possibility of selling the property in cases where it is destined exclusively for a specific function and in which there is a low level of fungibility. Here, the surface area is not the main driver of value, and hence a different criterion has to be used in order to estimate the value of that space. In cases involving a fungible property (i.e. office, logistic), it can simply be asserted that the future cash benefits will result from the sale or rental payments; on the other hand, for properties with a specific a business operating within them (such as hotels or shopping centres) it will be important to determine the maximum sustainable rent.

The Income methodologies involve the application of two different criteria which are based on different ways of measuring projected income, with different assumptions regarding the relationship between income and value:

- the Direct Capitalization Approach is used in order to convert the forecast for expected income over one single year into an indication of value, whereby the estimated income is divided by an appropriate capitalization rate (one income and one rate);

- the Financial Approach (based on DCF analysis models) is used in order to convert all future economic benefits into a present value, discounting all expected benefits (cash flows) at an appropriate discounting rate (expected total return).

Whilst the two criteria follow the same principles, there are significant methodological differences between them and the results may also be different. In particular, the differences between the Direct Capitalization Approach and the Financial Approach relate to the following points:

- the definition of economic benefit which the asset is able to produce:

- the Direct Capitalization Approach is based on an accounting measure of income (revenues);

- the Financial Approach identifies a cash flow (which may only occasionally coincide with the equivalent revenues);

- the time horizon considered:

- the Direct Capitalization Approach determines the value of an asset through an annual income and a capitalization rate related to this single reference period;

- the Financial Approach works with a multi-period process through the analysis on a time horizon extended to more than one period;

- the calculation algorithm:

- the Direct Capitalization Approach is based on the capitalization of a future benefit, transforming a current indicator of income into an indicator of value;

- the Financial Approach uses the discounting principle in order to anticipate future cash flows.

The Income methodologies are based on two different rates:

- the capitalization rate, which compares the value of an asset with one single-period income (Direct Capitalization Approach);

- the discount rate, which is used to discount the cash flows generated by an asset and which represents the total return required by the market for an investment with the same level of risk (Financial Approach).

Both rates are expected measures of returns:

- the capitalization rate is the expected yield, that is a measure of income return only (yield equal to income divided by price or OMV);

- the discount rate is the expected internal rate of return, that is a measure of total return (including both income and capital gain returns).

2.4.3.4 Choosing the correct approach to valuation

Real estate valuation is a fundamental problem when disbursing loans and, in order to be reliable, it is necessary that the approach used corresponds to the purpose of the valuation and the type of asset considered.

The Comparison methodologies usually predominate in the valuation of residential properties since it is easier to obtain comparable data from the ownership market than from the rental market. Moreover, even though they may differ from one another, at times significantly, residential properties are nonetheless more homogeneous in nature, and in many countries, being a prevalence of owner-occupied properties, their value is less affected by lease agreement conditions.

Conversely, for commercial properties the Income methodologies prevail, precisely due to the relative infrequency of transactions and the highly heterogeneous nature of properties; cash flows and yields are more homogenous than physical characteristics. Consider the case of shopping centres: the number of transactions within a given geographical market may even be nil over a certain period of time, which means that it will be necessary to refer to properties sold in other similar markets in order to obtain an indication of the relative yield. Moreover, the value of a shopping centre, as well as that of all properties in which the activity carried on inside has a direct impact on their economic value, is only indirectly dependent upon the surface area of the property. In this specific case, the shops' capacity to generate revenues is the key element in determining the rent, and is dependent upon factors such as the merchandising mix, the presence of anchor tenants, the overall quality of the project, and its location.

In addition, the Financial Approach appears to be the most complete for commercial properties, since it requires a consideration of all parameters necessary in order to determine the projected cash flows. This criterion has developed significantly over recent years, above all within sophisticated approaches which make it possible to measure the value's sensitivity to changes in different parameters. It therefore amounts to a risk management instrument, which is particularly precious and meets with the increasingly stringent legal requirements of some institutional investors. This approach is particularly suited also to the valuation of income generating residential properties as blocks of apartments and residences. The Income methodologies are increasingly establishing themselves in more mature markets in which the separation between owners (predominantly institutional investors) and users (both companies and families) is increasing: this therefore leads to the creation of a very significant rental market which makes it possible to determine the income generating capacity of properties in more detail.

Finally, the Cost Approach is the only possible way of valuing atypical assets, especially those for which there is no rental market and no sale market. In this case the Cost Approach will be useful, although it must be remembered that the value of this type of property will inevitably be dependent upon supply and demand dynamics which are reduced (or indeed entirely absent in cases involving some infrastructure non-producing cash flow). Finally, this approach makes it possible to determine the value of an area on a residual basis.

The appraiser should base his assessment on the different approaches when estimating the value of a property. Accordingly, for residential properties, it may be possible for example to pair up a comparison approach with an estimate made on the basis of the Direct Capitalization Approach. For commercial properties, on the other hand, the comparison approach may be used in conjunction with the Financial Approach. It is appropriate to insist on the need to analyse the differences in value resulting from the adoption of the different approaches. An analysis of these differences should prevail over a simple calculation of the average of the values obtained. In fact, it will make it possible to try to understand the reasons for the differences thus ensuring that the values allocated to the various different parameters for the valuation are plausible.

2.4.4 Due Diligence Process

The technical due diligence and the subsequent property valuation must be followed by a wider due diligence process, the purpose of which is to:

- carry out an administrative check, ascertaining whether the necessary commercial permits (if required) in order to manage real estate assets with rent agreements or going concern leases have been obtained, or verifying the status of the application to obtain those permits;

- review the compliance with the town planning requirements and building regulations, including consultation of the general city plan, building regulations and any town planning accords and/or plans, as well as an analysis of the relevant permits (building permit and works building notice); in several countries the sale of a property is prohibited under the town planning and building law if it has been built without the necessary consent;

- review mortgage and land registry documents in order to ensure that the documentation filed with the land registry corresponds to the property in its actual state;

- carry out a structural and technical plants check on the building and its facilities as well as of the state of maintenance;

- carry out an environmental check to ascertain whether there are any sources of pollution, including in the land, and hazardous material (e.g. asbestos, fuel tanks);

- check the energy certification documents and certificates.

2.4.5 Legal Due Diligence

The legal due diligence comprises the following stages:

- verification of full ownership of the property to be mortgaged by the party offering the security;

- verification that the property is not subject to any other securities or charges, or any other formality specified in the public land registers which may be otherwise detrimental to the mortgage security;

- verification of the legal capacity of all individuals involved in the loan agreement and in the issue of the relative guarantees;

- verification of the lease agreements in which the claims are granted/assigned/pledged to the lender;

- for some transactions (for example in case of the acquisition of the property by way of a share deal), a corporate and tax due diligence are also requested.

Depending upon the legislative arrangements, these stages of the review will generally be conducted by the solicitor or barrister responsible for the drafting of the loan agreement or for authenticating the signatures, who will then draw up the reports attesting ownership of the properties provided as security and the fact that they are free from other charges.