Chapter 4

Loan Repayment, Interest, and Renegotiation

In the first part1 of this chapter the most commonly used loan repayment schedules and interest calculation techniques are described, while in the second part issues related to loan renegotiation and restructuring are dealt with.

Since it is very important to have a loan repayment schedule that fits the operating cash flows of the financed real estate project, the described loan repayment schedules are the most typical scheme, but any kind of variation is possible depending on the financing agreement.2

4.1 Bullet payments

Loans providing for bullet payments, also called zero amortizing (interest only) constant payment loans, require the payment of the entire principal of the loan (and in rare cases also all of the interest3 ) upon maturity of the loan. As the name easily brings to mind, the periodical payment will simply be in the form of an interest payment. Thus, the outstanding loan balances at the beginning of each period (BoP) will be a constant value equalling the loan value.

4.2 Pre-amortizing (semi-bullet)

Pre-amortizing (or semi-bullet) is an interest-only repayment plan that stipulates the payment of interest only for a certain period of time. The period is referred to as the interest-only period, as against the subsequent repayment period during which interest is paid regularly and the principal loaned is repaid. They are common in development projects to fund construction costs: only after the property has been built and/or marketed is the principal repaid.

4.3 Balloon payment

Loans providing for balloon payments require the payment of interest and the redemption of part of the principal during the term of the loan; the outstanding principal will then be repaid in full upon maturity (by selling the property or refinancing), unless the term of the loan is extended.

In this case there is a non-zero outstanding loan balance at the end of the loan term, thus allowing the borrower to make periodical payments that are lower than those under the provision of a fully amortizing loan. The value of the outstanding loan balance at the end of the loan term is generally referred to as a balloon payment (BP).

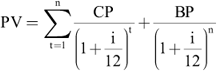

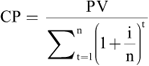

In order to calculate the value of the constant periodical payment (CP) the present value of an annuity formula is applied, solving it for CP. The value in time of the balloon payment is also considered, assuming 12 periodic (monthly) payments (per annum).

from which CP can be calculated as:

4.4 Fully amortizing repayment plans

Fully amortizing is the most commonly used form of repayment for financing in the real estate sector. A constant periodical payment – monthly, quarterly, or annually – is calculated based on the loan value at a fixed interest rate. Each periodical payment thus contains both an interest payment component and the repayment of principal. The interest payment component is simply calculated applying the relevant interest rate (fixed or floating) to the outstanding loan balance at the beginning of the period, while the repayment of the principal is the difference between the constant payment and the interest payment.4

For loans which are repayable in instalments, a repayment plan will be agreed upon in advance, which may come in different forms.

4.4.1 Fixed-Capital Loan Repayment Plan

In fixed-capital repayment plans each instalment will repay a fixed principal component, along with a decreasing interest component calculated on the outstanding debt; only the latter component varies over time. This form is very common in residential loans. In other words, instalments remain the same until the end of the plan; the principal component increases over time, whilst the interest component falls in line with the reduction in the outstanding debt (clearly, if a floating-rate rate is chosen, the amount of interest due and hence the amount of each instalment may rise or fall).

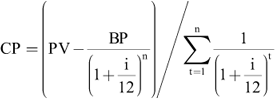

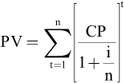

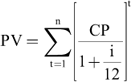

In order to calculate the value of the constant periodical payment (CP), the present value of an annuity formula is used:

- PV is the value of the loan amount

- n is the number of periods per annum

from which it can be easily derived:

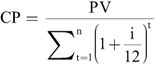

The same formulas applied to monthly constant periodical payments are:

from which it can be easily derived:

At the end of the loan, the original debt amount will be completely amortized and reimbursed.

4.4.2 Floating-Rate Loan Repayment Plan

In the case of a floating-rate loan (interest rate adjusted loan) the outstanding loan balance at the end of each payment period depends on interest rates level in the market (e.g. EURIBOR or LIBOR).

There are several benefits related to using such an interest based index, that is:

- interest rates are a reflection of investors' future expectations;

- interest rates are thus forward looking;

- adjustments can be more timely.

In the residential loan market there are also Hybrid Adjustable Rate Loans where the loan generally functions as a fixed-rate loan during the initial three, five, or seven years. After this period the loan is adjusted to reflect new prices and interest rates in the economy. Payments after these initial periods are generally adjusted every year.

An example is presented in Figure 4.8. A loan amount of €100,000 for a 20 year term is taken out at a 6% nominal annual interest rate. The initial monthly payment would then be €707.29.

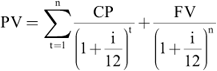

The outstanding loan balance at the end of Period 1 is calculated solving the following formula for FV equal to zero:

with CP = €707.29, PV = €100,000, i = 6%, n = 12

If at the end of Year 1 nominal annual interest rates rise to 6.5%, the new monthly payment would be calculated using the same formula as above but solving for CP with:

- FV = 0

- PV = outstanding loan balance at the end of Year 1

- n = 29

- i = 6.5%

It should be noted that a floating-rate loan does not completely eliminate any risk for the lender. Indeed, it might be the case that the interest rate applicable to the loan is now adjusted to 6.5%, but then during the next two months interest rates rise to 6.75%. The lender will then incur a loss for the remaining time until the next adjustment takes place. This simply means that the shorter the time between adjustments, the lower the risk incurred by the lender. This risk, of course, should be reflected in the level of interest rate settled in the loan agreement.

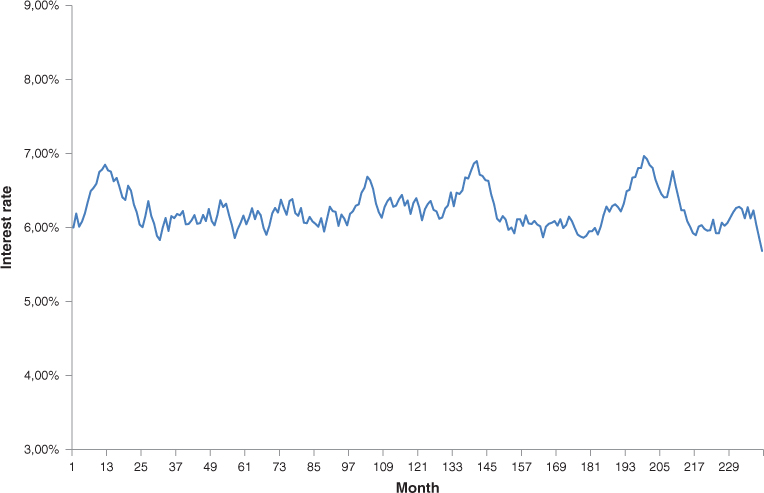

Figure 4.7 shows the loan pattern for an interest rate adjusted loan. It is similar to what was previously seen in the case of a fully amortizing loan. The difference now is that it is more an exercise of recalculating the periodic interest payments owed to the lender every time the reference interest rate in the market changes, as showed in the example in Figure 4.8.

Figure 4.7 Example of floating-rate pattern

4.4.3 Loan with Interest Rate Caps

In this type of loan, in order to limit the upside risk of an elevated payment for the borrower, a Cap (acting as a limit) is imposed on the increase that the interest rate may follow.5 There could be some loan agreements where such a limit is imposed on the overall amount owed by the borrower to the lender and not simply on the interest rate. Of course, an Interest Rate Cap also acts as a sort of payment Cap limiting the payment amount that the borrower may owe to the lender. In other words, it is simply a matter of different formulations aimed at the same purpose of preserving the ability of the borrower to make repayments.

In case of a loan amount of €100,000 for a 20 year period taken out at a 6% nominal annual interest rate, the initial monthly payment would be €707.29.

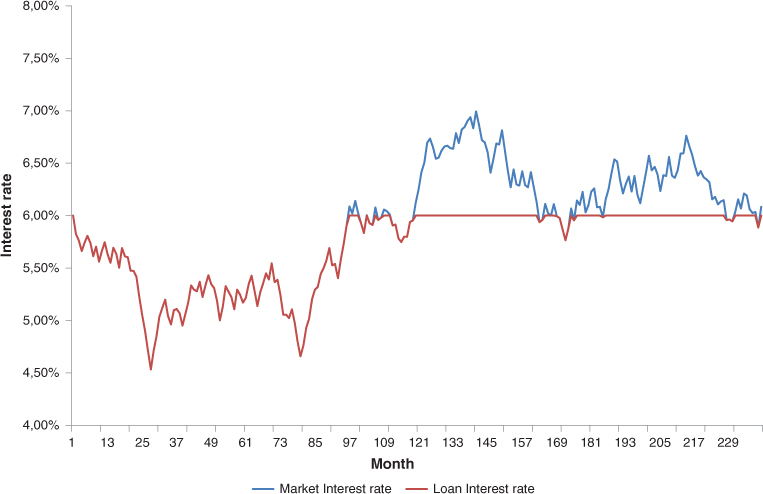

The Interest Rate Cap states that 6% is the maximum interest rate applicable, as shown in Figure 4.9 where the interest rate pattern both for the market interest rate and the actual loan interest rate is represented.

Figure 4.9 Interest rate with Cap pattern

Basically, whenever prevailing interest rates in the market are below the 6% level, monthly payments are based on that interest level, while in case interest rates are above that level, 6% is the interest rate applied to service the loan.

In a loan agreement with this setup, the lender will lose the opportunity to make more money every time interest rates move beyond the fixed Cap level. Compared to loans where there are no restrictions on interest rate movements, the lender should now be remunerated for the risk of losing money; this remuneration for risk should be expressed with a loan agreement that is initially based on an interest rate higher than similar loan contracts with no such Interest Rate Cap restrictions.

4.5 Other repayment schedules

The possibility to create repayment schedules is virtually limitless. In this paragraph some other techniques, although not very common, are presented.

4.5.1 Negative Amortizing Constant Payment Loan

In a negative amortizing constant payment loan the borrower and the lender negotiate a loan agreement according to which the outstanding loan balance at the end of the loan term will be greater than the loan amount itself and thus the periodic payment will be lower than the interest amount due periodically. The outstanding loan value at the end of the loan term will be simply the sum of the loan amount plus all the annual differences between the interest payments and the monthly payments.

4.5.2 Declining Payment Loan with Constant Amortizing

In this variant of repayment, the constant amortization of the loan amount is first computed. The monthly payment is then calculated as the sum of this constant amortization plus the interest payment on the outstanding loan balance at the beginning of the period. The monthly payment will be decreasing to a value close to the amortization value.

4.6 Restructuring and renegotiation of real estate loans

Restructuring and renegotiation are the terms commonly used in order to classify all situations involving deferment periods, extensions, amendments to contractual clauses, as well as the settlement of outstanding debts due to banks by borrowers which are temporarily unable to comply with their obligations.

Generally speaking, the term restructuring is used to classify transactions concluded between the lender and the borrower and is intended to redefine the overall agreement of the latter's debt exposure. Within this context, these transactions are also classified using the term consolidation. Renegotiation instead generally involves one individual financial relationship or, otherwise, a homogeneous series of relationships in which some elements of the loan agreement (term, interest rate, repayment plan) are amended, not necessarily in order to deal with a situation in which the borrower has defaulted. Usually they are characterized by granting certain facilities to a borrower who is encountering temporary difficulties in honouring the terms of the loan or they represent the conclusion of market transactions aimed at securing the client's loyalty. These may involve changes to interest rates, payment terms, maturity dates, and repayment plans (the waivers), or alternatively the granting of a new loan to replace the previous one, which will then be redeemed with the proceeds of the new loan.

Generally speaking, these transactions may relate both to unsecured short-term debts as well as to medium- and long-term debts backed up by a mortgage security.

Restructuring techniques may involve any of the following:

- the grant of a new loan;

- the deferral of payment deadlines and the concession of respite periods;6

- the definition of a loan restructuring agreement.

In many cases restructuring may involve a moratorium on the payment of overdue instalments (generally on the principal in order to permit the borrower to overcome the temporary difficulties without defaulting on the loan). For example, in a case where a tenant paying a significant amount in rent terminates its lease earlier or does not renew the lease upon expiry, it may be necessary to reduce the amount of the instalments falling due pending the arrival of a new tenant by negotiating a suspension on payments of the principal.

4.6.1 Grant of a New Loan

Restructuring could also involve the grant of a new loan, thereby enabling overdue outstanding debts to be paid. The new loan will mean that it is necessary to conclude a new loan agreement and reconstitute all of the securities ex novo (including the mortgage).

The borrower will therefore have to bear all of the costs (including taxes) relating to the redemption of the existing loan, as well as those relating to the granting of the new loan. Depending upon the legislative arrangements the bank's guarantee may be weakened since, firstly, the period of time necessary in order to constitute and/or consolidate the mortgage will re-commence and, secondly, it will be open to a new risk of revocation, since both the establishment of the new mortgage as well as the payment redeeming the previous loan may be revoked.

4.6.2 Deferral of Payment Deadlines

A deferral replaces the overdue time limit with a new time limit. A distinction is drawn between a deferral and a respite period: in the latter case the borrower only ceases to be in arrears with payments after it has complied with the obligation within the deferred time limit.

In other words, the respite period implies a situation in which a time limit is replaced only if the performance occurs before expiry of the new time limit set by the lender. This means that a deferral involves the replacement of the overdue time limit with a new one, with the result that the borrower is no longer in arrears (and does not pay the default interest). During a respite period on the other hand, the status of the loan as being in arrears continues until obligations are honoured upon conclusion of the respite period. In both cases the bank stops demanding the repayment of the loan and does not enforce the guarantees, signing a “standstill agreement” with the borrower.

4.6.3 Restructuring Arrangement

The conclusion of a restructuring agreement is generally premised upon a standstill agreement (i.e. a pactum de non petendo), which is a common feature both of loan restructuring agreements (concluded between a debtor and (all of) its creditors in order to resolve a crisis situation) as well as loan renegotiations (concerning the individual relationship between the bank and the borrower).

The standstill agreement (pactum de non petendo) may be defined as an agreement which has the purpose of granting a deferral of loan payment deadlines which are overdue or have not yet fallen due. Such an agreement does not redeem the loan, but rather amends the terms [of repayment] of original loan agreement, thus preventing the lender from enforcing the – as a matter of principle – overdue loan instalments , the payment of which is deferred until the end of the amortization of the original loan. This means that the overdue loan instalments (overdue interest, overdue capital repayments, and interest on arrears) are repaid by the borrower along with the outstanding debt on a deferred basis, following the original repayment plan in place for the outstanding debt and including, if necessary, a deferral of the final maturity date.

When concluding this arrangement, the parties generally execute an agreement (entitled “Variation of the amortization plan” or “Loan renegotiation agreement” or “Loan restructuring agreement” or again “Loan restructuring agreement with variation to the repayment plan”) in which, after referring in the preamble to the original agreement(s) grounding the obligation which is to be renegotiated, the borrower acknowledges that it owes certain amounts of money to the lender by way of residual capital, overdue loan instalments (overdue capital and interest payments), and interest on arrears.

As regards default interests, the bank will generally require that the borrower pays such interest (either in full or in part) before concluding the restructuring agreement. Alternatively, a separate agreement may be concluded to regulate their repayment. The payment of default interest (either in full or in part) is an indication of the borrower's actual intention (and financial capacity) to honour his obligations.

The renegotiation agreements concluded by bank and borrower acknowledge the level of the debt and set forth arrangements to govern the repayment of the overdue amounts along with the outstanding debt. Such agreements may come in various forms.

- An agreement that the interest provided for under the loan agreement (which have not changed) will accrue on the overdue amounts instead of interest on arrears. Accordingly, the borrower undertakes to repay the overdue amounts in instalments along with the outstanding debt, following the repayment plan put in place for the outstanding debt. This operation is defined as the “capitalization of arrears”. In order to determine instalment amounts (to repay both the outstanding debt as well as the overdue amounts) which are lower than those originally agreed to and which are sustainable for the borrower, the term of the loan will be extended accordingly.

- An agreement that fixed-rate loan repayments will be made at a level which is sustainable for the borrower (and hence lower than that originally agreed to) until the original maturity of the loan. Instalments paid are allocated by the bank first to the payment of the interest share provided for under the original repayment plan, and thereafter as principal repayments (again as specified under the original repayment plan). The unpaid residual principal on each instalment is then capitalized and, along with the outstanding debt (which is also capitalized), will be repaid by the borrower at the end of the life of the loan either as a lump sum or again by fixed-rate loan repayments. In the latter case, the parties will agree to amend the repayment term for the loan. The amounts capitalized will accrue interest at a rate which is, normally, equivalent to the interest rate for the loan, although if no such agreement is reached interest will accrue at the default rate on these overdue capital instalments.

In these restructuring agreements the parties generally confirm all of the terms, clauses, and conditions contained in the original loan agreement which will not be amended in the restructuring agreement, and will expressly preclude any intention to novate the obligations created under that agreement. Moreover, the guarantors will continue to be parties in order to confirm the securities provided for the original loan. In many cases a clause is included whereby the bank reserves the right to restore all of the original contractual terms and conditions if the borrower fails to abide by the restructuring agreement.