A diversity science approach to climate change

Adam R. Pearson1 and Jonathon P. Schuldt2, 1Pomona College, Claremont, CA, United States, 2Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, United States

Abstract

This chapter reviews psychological research on diversity and its implications for understanding public engagement with climate change. Meaningful and timely action on climate change will require engaging a diverse set of stakeholders, both within and between nations, in order to develop and implement more effective mitigation and adaptation policies; as such, there is an urgent need to better understand factors that drive differential engagement within increasingly diverse, pluralistic societies. In this chapter, we draw from current psychological perspectives on social identity, identity-based motivation, and belonging to explore how race, ethnicity, and class shape public engagement with the issue, and identify key social psychological processes that may contribute to persistent and substantial disparities in the environmental sector. We highlight empirical findings that illustrate the value of this approach, identify major gaps in current understanding, and discuss new avenues for future research on group-level conduits and barriers to climate change engagement.

Keywords

Diversity; race/ethnicity; social identity; intragroup processes; stereotyping; intergroup relations

Acknowledgements

Preparation of this chapter was supported by a David L. Hirsch III and Susan H. Hirsch Research Initiation Grant awarded to the first author.

5.1 A diversity science approach to climate change

For Latinos, our strong positions on questions pertaining to the importance of stewardship of our natural environment and conservation of resources reflect long-held cultural tenets taught to us not as environmentalism, but based more on common sense, economic necessity, and good citizenry.—Mark Magaña, President/Founder GreenLatinos

When Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans in late August of 2005, virtually all inhabitants of the city were affected and displaced, but impacts fell disproportionately on racial and ethnic minority and low-income communities. Disparities were evident in a comparison of undamaged vs damaged areas, which had a higher proportion of Black and low-income residents (Masozera, Bailey, & Kerchner, 2007), in the slower rates of return to the city by Blacks compared to Whites (Fussell, Sastry, & VanLandingham, 2010), and in higher mortality rates (estimated at 1.7–4 times greater) among Black residents, relative to Whites (Brunkard, Namulanda, & Ratard, 2008). Events such as these highlight the significant social dimensions of natural disasters, such as hurricanes, that are projected to increase in intensity as the planet warms (Bolin, 2006; Knutson et al., 2010; Laska & Morrow, 2006). Yet, despite growing attention to inequity in climate-related impacts, and to racial and ethnic disparities within psychology generally, scholars have only recently begun to apply behavioral science approaches to understand the diversity of human responses to climate change in pluralistic societies.

This chapter reviews the insights and applications of diversity science to the psychological study of climate change. Although many identity dimensions are relevant to the study of diversity (e.g., age, religion, cultural diversity), in this chapter, we focus on racial, ethnic, and class differences in climate change engagement, consistent with the growing empirical literatures on these dimensions in the study of climate change (see Pearson, Ballew, Naiman, & Schuldt, 2017). We begin by considering why diversity matters for understanding public engagement with climate change and describe what a diversity science approach can contribute to current social science perspectives in this area. We then review empirical evidence for racial, ethnic, and class differences in climate change attitudes, beliefs, and behavior that highlight the differing ways that groups engage with the issue. Next, we discuss social psychological processes that can enhance and hinder engagement among groups that remain substantially underrepresented within the environmental movement. We conclude by considering the implications of a diversity science approach for developing effective organizational practices and policies that seek to broaden public participation in environmental decision-making.

5.2 Why diversity matters for climate change

Due to increased transnational migration and demographic shifts within countries, many industrialized nations that contribute disproportionately to climate change and have the greatest influence on international policy-making, such as the United States and nations in Western Europe, are also becoming more diverse. Within the United States, racial and ethnic minorities accounted for over 92% of the nation’s population growth in the decade from 2000 to 2010, with current estimates indicating that a majority of the under-18 US population will identify as a member of a racial or ethnic minority by 2020 (Colby & Ortman, 2015; Heimlich, 2011). Beyond the United States, similar demographic changes are projected for Europe and Australasia with the arrival of humanitarian entrants and skilled migrants, with migration set to increase as a result of climate change and its impacts in the coming decades (Piguet, Pécoud, & de Guchteneire, 2011; United Nations Development Programme, (2007). These shifting demographics underscore a need for research that can inform government and organizational efforts to broaden public participation in climate discourse and decision-making in increasingly diverse societies, and particularly among groups disproportionately affected by climate change.

Although climate change is a global threat, its impacts are not evenly distributed but instead fall disproportionately on the world’s poor and politically disenfranchised (e.g., Miranda, Hastings, Aldy, & Schlesinger, 2011; Wilson, Richard, Joseph, & Williams, 2010). Members of socioeconomically disadvantaged groups, such as racial and ethnic minorities and the poor, experience harmful impacts of climate change at substantially greater levels than those of more advantaged groups, such as Whites and the more affluent (Cutter, Emrich, Webb, & Morath, 2009; United Nations Development Programme, (2007). To make matters worse, global inequality is expected to increase substantially within the next several decades as wealthier nations at higher latitudes, such as Canada and Scandinavia, stand to benefit economically from regional warming, whereas poorer nations closer to the equator will be negatively affected. The effects of climate change on global inequality may further exacerbate and compound climate disparities as poorer countries struggle to adapt to its effects (Burke, Hsiang, & Miguel, 2015).

Beyond fundamental issues of equity, there are other important reasons for studying factors that broaden and sustain public engagement on climate change. In particular, the well-documented political divide on climate change within the United States and some European nations (see Dunlap, McCright, & Yarosh, 2016) and wavering public interest in climate change globally (Brulle, Carmichael, & Jenkins, 2012) present formidable challenges for organizations and policy-makers who are looking to build consensus and galvanize public support for adaptation and mitigation policies. Moreover, research on group decision-making suggests that diversity in teams promotes more effective problem solving and the development of more innovative solutions (e.g., Hong & Page, 2004; Levine et al., 2014)—precisely the kind of solutions needed to avert the worst effects of climate change. Understanding factors that enhance diversity in climate decision-making may, thus, not only address inequity by giving voice to groups disproportionately affected by climate change but also spur the development of new solutions that are urgently needed to help communities and nations adapt to a changing climate.

5.2.1 A diversity science approach

Insights from diversity science can help guide psychological inquiry on factors that shape public engagement on climate change. Diversity science represents an interdisciplinary approach that uses behavioral science methodologies to consider how people create, interpret, and maintain group differences, as well as the psychological and societal consequences of these distinctions (Plaut, 2010). Thus, a diversity science approach can help to illuminate key motivational underpinnings of environmental engagement (i.e., social psychological mechanisms) and the ways in which both intra- and intergroup processes can powerfully shape these motivations.

Diversity science, as an interdisciplinary approach, emerged from social psychology and organizational behavior to understand psychological processes underpinning racial and ethnic disparities within organizations and academia. The approach has since been applied to a wide range of fields, including healthcare, employment, education, criminal justice, and organizational behavior (for reviews, see Apfelbaum, Norton, & Sommers, 2012; Cheryan, Ziegler, Montoya, & Jiang, 2017; Dovidio, Gaertner, Ufkes, Saguy, & Pearson, 2016; Cohen, Garcia, & Goyer, 2017; Oyserman & Lewis, 2017; Plaut, 2010; Yeager & Walton, 2011). Importantly, within each of these domains, a diversity science approach considers how the perspectives of both majority and minority group members can contribute to intergroup disparities. In the following sections, we extend a diversity science framework to the domain of climate change communication and organizational practice to explore three core questions: What motivates people to join environmental professions, organizations, and initiatives? How do different ways of framing sustainability challenges influence who engages with climate change advocacy? And how do both majority and minority group perspectives shape environmental attitudes and collective action in increasingly diverse societies, such as the United States?

In their review of public opinion work on climate change, Wolf and Moser (2011) distinguish between climate change understandings (acquisition and use of knowledge about climate change), perceptions (e.g., subjective experience as well as interpretations of others’ beliefs and actions), and engagement (a motivational state that can include cognitive, emotional, and/or behavioral dimensions) as distinct but complementary ways that individuals respond to climate change. In the following sections, we summarize research and theory that examine how social groups shape each of these dimensions, with a particular focus on psychological processes that may influence engagement at the collective level (e.g., activism and participation in environmental organizations). We begin by reviewing empirical research highlighting the key role of identity processes in climate change engagement and then turn to theoretical perspectives within psychology that offer additional insights into the ways that group memberships can impact engagement, particularly for members of traditionally underrepresented groups.

5.2.2 Identity-based approaches to climate change engagement

A growing body of research on environmental behavior suggests that social identities can affect both how people perceive environmental risks and how they engage with groups working to address them (Feygina, 2013; Fielding, Hornsey, & Swim, 2014; Pearson, Schuldt, & Romero-Canyas, 2016; Swim & Becker, 2012). Moreover, interventions that capitalize on social identity processes have been shown to be particularly effective at motivating cooperation in resource dilemmas (see Brewer & Silver, 2000; Ostrom, 1990; Van Vugt, 2009), and engagement with activist causes, generally (see Tyler & Blader, 2000).

According to the social identity model of collective action (van Zomeren, Postmes, & Spears, 2008; see also van Zomeren, Spears, & Leach, 2010), people take action when they identify with groups attempting to mobilize action, believe that their group’s actions can be effective, and experience strong emotional reactions (e.g., feelings of injustice). For instance, a series of studies examining what motivates people to join local climate change initiatives found that the extent to which people identified with the group involved in the cause was a strong predictor of motivation to participate, over and above concerns about costs and benefits of participating (Bamberg, Rees, & Seebauer, 2015; see also Chapter 8: Environmental protection through societal change: What psychology knows about collective climate action—and what it needs to find out). In addition, whereas those who more strongly identified with the group showed intrinsic motivations to participate (e.g., viewing the group’s goals as more important than one’s personal reasons for participating), those with low levels of identification were more extrinsically motivated, focusing on personal costs and benefits of participating.

The group engagement model (Tyler & Blader, 2003) similarly posits that identity motivations are central to psychological and behavioral engagement with groups, and that perceptions of procedural justice (e.g., inclusion in decision-making processes, being recognized and treated with respect) are a primary mechanism through which people assess, establish, and maintain group ties. Process fairness provides people with reassurance that a group values and represents their interests, which in turn fosters a sense of connection and identification with the group, its members, and their goals. Including members of traditionally underrepresented groups as meaningful stakeholders in climate change decision-making is, thus, important not only for ensuring greater equity in decision-making (e.g., addressing problems that matter to these groups) but also for promoting solidarity with groups working to address climate change.

The unique complexity (e.g., implicating both biophysical and social systems), temporal features, and geographic scale of climate change that make it difficult to understand and predict can also directly impact social identity processes. Uncertainty about the causes and long-term effects of climate change is often viewed as a chief barrier to public mobilization (Barrett & Dannenberg, 2014; Budescu, Broomell, & Por, 2009; Pidgeon & Fischhoff, 2011). However, uncertainty can also increase collective action by enhancing identification with groups engaged in activist causes. Generally, people participate in social movements not only to effect social change but also to establish social identities and strengthen social ties with fellow group members (Hogg, 2007; Klandermans, 2004). High and enduring uncertainty due to economic collapse or natural disasters can lead people to seek and affiliate with groups that are ideologically more extreme, or make existing groups more extreme, to reduce the uncertainty (see Hogg, 2007). Thus, uncertainty surrounding climate change may heighten the importance of social identities and impact the strength of group ties in ways that may hinder or enhance collective efforts to address the problem.

Research on partisan influences provides additional evidence of the role of group identities (e.g., party affiliations) in shaping public opinion on climate change. People’s beliefs and experiences, including their perceptions of other group members’ beliefs, form an important basis for how they perceive social and political issues (Wood & Vedlitz, 2007). Individuals tend to adopt beliefs that are shared by members of salient ingroups and may resist revision of these beliefs when they are confronted with conflicting information (Kahan, Braman, Gastil, Slovic, & Mertz, 2007; McCright & Dunlap, 2011a; Schuldt & Roh, 2014). Similarly, the elite cues hypothesis (Krosnick, Holbrook, & Visser, 2000) suggests that people are especially likely to rely on information from high-status ingroup members (e.g., political leaders) when an issue is perceived to be complex or controversial. Consistent with these perspectives, several studies have shown that as education and science literacy increase within the US public, political polarization on climate change becomes stronger, suggesting that people process climate-related information in ways that reinforce their prior political stance (e.g., Hamilton, 2011).

5.3 Identity influences beyond partisan politics

Compared to partisan influences, considerably less attention has been paid to the role of nonpartisan social identities and group memberships, such as those related to race, ethnicity, and social class, that have also been shown to influence how people assess environmental risks (for reviews, see Ferguson, McDonald, & Branscombe, 2016; Pearson & Schuldt, 2015; Pearson et al., 2016; Schuldt & Pearson, 2016). Early studies often conflated environmental attitudes with specific behaviors, such as outdoor recreation (e.g., visits to national parks), membership in environmental organizations, and charitable donations. This measurement problem contributed to the belief that non-Whites were less concerned about the environment than Whites (for reviews, see Mohai, 2008; Macias, 2016b; and Taylor, 1989). Spurred largely by work in the environmental justice field over the past two decades, there has been a notable shift away from assessing environmental concern based primarily on attitudes toward conservation (e.g., protection of natural resources) to incorporating measures of environmental risk, and particularly perceived exposure to environmental hazards, such as health risks associated with industrial pollution that disproportionately affect Black and Latino communities (see Arp & Kenny, 1996; Bullard, Johnson, & Torres, 2011; Jones & Rainey, 2006; Macias, 2016a; Mohai, 2008; Mohai & Bryant, 1998).

5.3.1 Evidence for the roles of racial and ethnic identities

US opinion polls reveal a racial/ethnic gap in environmental concern—including about climate change, specifically—with non-White minorities expressing a level of concern that often exceeds that expressed by Whites (e.g., Dietz, Dan, & Shwom, 2007; Guber, 2013; Leiserowitz & Akerlof, 2010; Macias, 2016a; McCright & Dunlap, 2011a; Speiser & Krygsman, 2014; Whittaker, Segura, & Bowler, 2005; Williams & Florez, 2002). For instance, an analysis of US Gallup Polls between 2001 and 2010 revealed that relative to Whites, non-Whites reported greater concern that climate change would pose a serious threat within their lifetime (McCright & Dunlap, 2011a), and this racial/ethnic gap in concern remained when controlling for other variables found to correlate with climate change beliefs, including income, education, religiosity, and political orientation (see Guber, 2013). Similarly, using data from the 2010 General Social Survey (GSS), Macias (2016a) found that non-Whites expressed greater concern for climate change than Whites, controlling for effects of age, gender, household income, education, rural/urban location, and political ideology. Moreover, non-Whites’ concerns about climate change exceeded concern for more localized issues, such as air pollution from cars and industry1.

Research on ethnicity and acculturation processes also suggests a unique role of ethnic identities in climate change engagement. For instance, within the United States, Asians and Latinos, the fastest growing minority groups, consistently show the highest levels of concern about climate change among all racial and ethnic groups, and particularly among first-generation immigrants (e.g., Jones, Cox, & Navarro-Rivera, 2014; Leiserowitz & Akerlof, 2010; Macias, 2016a, 2016b). Social psychological research has identified distinct value orientations among these groups, such as a more interdependent, collectivistic orientation that prioritizes social harmony, respect, and concern for family and community over individuality and self-interest (Holloway, Waldrip, & Ickes, 2009)—values that are also associated with proenvironmental attitudes and behaviors (see Milfont, 2012). For instance, Schultz (2002) found that people from collectivist cultures generally have greater biospheric concerns than those from individualist cultures. These findings highlight the need for additional research that investigates key cultural factors that impact environmental attitudes and beliefs.

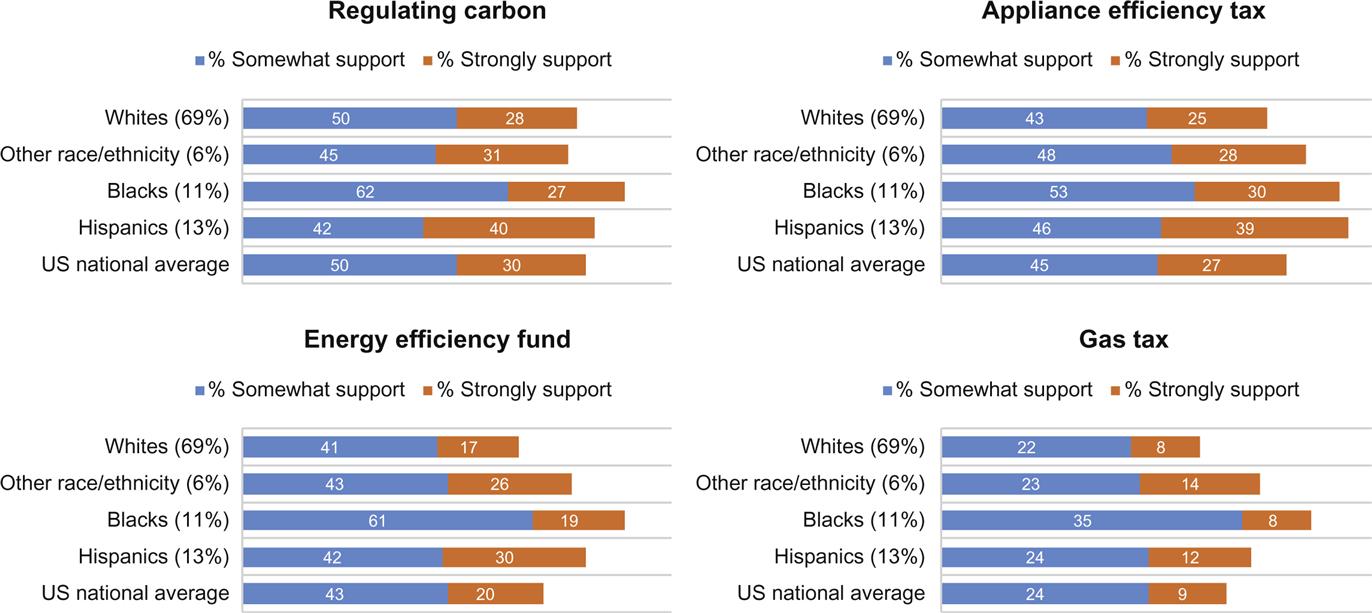

These gaps in concern translate to differences in policy support at both local and national levels. For instance, Blacks and Latinos typically express higher levels of support for national climate and energy policies than Whites, even when these policies incur a short-term cost (e.g., taxes). This includes proportionally higher support for regulating carbon emissions, improving fuel economy and household energy efficiency standards, and increasing taxes to mitigate climate change (see Fig. 5.1; Leiserowitz & Akerlof, 2010; see also Dietz et al., 2007; Leiserowitz, 2006; and Krygsman, Speiser, & Lake, 2016). A similar pattern is evident even among policy-makers, with research suggesting that Hispanic and African-American members of Congress are more likely than White members to vote proenvironmentally (Ard & Mohai, 2011).

Some scholars have argued that environmental beliefs, including skepticism about climate change, can serve an “identity-protective” function to buffer the status afforded by advantaged group memberships (Kahan et al., 2007). Individuals from higher status groups (e.g., White males) are especially likely to resist regulatory policies aimed at reducing environmental risks and perceive them as challenges to established social, economic, and political institutions (Feygina et al., 2010; McCright & Dunlap, 2011b). Policies aimed at mitigating climate change can represent a challenge to the status quo, which, in turn, may prompt responses to defend and legitimize those advantageous systems (e.g., denying climate change or its human causes; see Hennes, Ruisch, Feygina, Monteiro, & Jost, 2016).

Related work on the “White male effect” in environmental risk perception has highlighted the ways that gender, race, and political orientation can intersect to predict beliefs about climate change and support for mitigation policy. For instance, conservative White males are significantly more likely than other groups in the United States to deny the existence of climate change (Kahan, Jenkins-Smith, & Braman, 2011; Finucane, Slovic, Mertz, Flynn, & Satterfield, 2000; McCright & Dunlap, 2013). Complementing these findings, individuals from higher status groups who are also more likely to perceive prevailing group hierarchies as just and fair (e.g., conservative White males) are most likely to resist policies aimed at regulating environmental risks and to perceive them as threatening established social, economic, and political systems (Feygina et al. 2010; McCright & Dunlap, 2011a).

5.3.2 An attitude-participation gap in minority engagement

Although US minorities often report higher levels of environmental concern than their White counterparts, they nevertheless remain substantially underrepresented in environmental organizations and professions. For instance, an analysis of occupational disparities revealed that despite constituting 38% of the US population and nearly one-third of the US science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) workforce, non-Whites account for only 10%–15% of environmental science professionals (Pearson & Schuldt, 2014). These findings mirror disparities in the US environmental sector more generally. A study of 293 US environmental nonprofits, government agencies, and grant-making foundations found that non-Whites comprised no more than 16% of staff in all three types of institutions (Taylor, 2014). Within academia, a similar picture emerges. A survey of US faculty across 17 environmental disciplines revealed only 11% minority representation, with a majority of faculty reporting having either one or no faculty of color in their department (Taylor, 2010).

Efforts to address disparities in the environmental sector have frequently focused on increasing the salience of environmental risks, and in so doing, appear to assume that low environmental awareness is the chief barrier to engagement—an assumption at odds with the high levels of risk awareness and environmental concern expressed by US racial and ethnic minorities and lower income individuals, discussed above (e.g., Dietz et al., 2007; Guber, 2013; Leiserowitz & Akerlof, 2010). Moreover, surveys reveal substantial numbers of racial and ethnic minorities who are qualified to work in the environmental sector (Taylor, 2010, 2014). Thus, other factors may be at play.

Although the above findings document a persistent and substantial attitude-participation gap in minority engagement, theoretically informed approaches aimed at bridging this gap are lacking. Much of the social science scholarship, to-date, has focused on key structural barriers, such as insular hiring practices and limited minority outreach, that impede the recruitment and retention of racial and ethnic minorities within the environmental sector (see Taylor, 2014; for a review). In the following sections, we explore complementary psychological processes that may contribute to the attitude-participation gap and represent additional pathways for intervention.

5.4 Motivational barriers across groups

Research suggests that differing group concerns—particularly related to differing levels of vulnerability to harms associated with environmental hazards—are central to understanding how majority and minority groups engage with the problem of climate change and assess its risks.

According to the differential vulnerability hypothesis, non-Whites in the United States may feel more vulnerable to the effects of climate change than Whites, in part, because of their less privileged position in society (Flynn, Slovic, & Mertz, 1994; Satterfield, Mertz, & Slovic, 2004). Consistent with this hypothesis, Adeola (2004) found that disproportionate exposure to environmental hazards predicted Blacks’ greater perception of a wide range of environmental risks, including those associated with industrial emissions. Similarly, in a nationally representative U.S sample, Satterfield et al. (2004) found that the racial/ethnic gap in environmental concern was partially accounted for by non-Whites’ greater awareness of disproportionate environmental hazards and greater perceived vulnerability—effects obtained independent of those of income, education, and political orientation (see also Mohai, 2003).

Similar effects have been documented for lower income individuals. Stokes, Wike, and Carle (2015) reported that Americans making less (vs more) than $50,000 a year were more likely to believe that climate change is a very serious problem and were more concerned that it would harm them personally. Whereas this result may partly reflect the economic means of wealthier individuals to adapt to threats posed by climate change (see Macias, 2016b; Semenza et al., 2008), poorer people may feel a heightened sense of vulnerability to negative impacts both because they lack financial means and because the places where they typically live and work are more vulnerable to climate impacts (Crona, Wutich, Brewis, & Gartin, 2013; Mirza, 2003; Swim et al., 2009).

These differences in risk perceptions mirror the reality that low-income and minority communities in many industrialized nations suffer disproportionately from a wide range of environmental hazards, as mentioned above. For instance, due to persistent racial segregation and discrimination in the real estate economy, US Blacks and Latinos are substantially more likely to live near hazardous industrial sites and high-pollution-emitting power plants (Bolin, Grineski, & Collins, 2005; Bullard et al., 2011; Jones & Rainey, 2006; Mohai, 2008). As a result, non-Whites experience higher levels of smog exposure than equivalent-income Whites, with racial disparities in exposure up to 20 times greater than disparities by income (Clark, Millet, & Marshall, 2014).

5.4.1 Differential motives in climate change engagement

Given their greater vulnerability and awareness of inequities (Satterfield et al., 2004), racial and ethnic minorities and members of other socioeconomically disadvantaged groups may be motivated by concerns that are less rooted in political orientation (i.e., party identification or political ideology) compared to Whites and members of advantaged groups. Consistent with this reasoning, in a large nationally representative survey of the US public, we (Schuldt & Pearson, 2016) found that relative to Whites, racial and ethnic minorities’ climate change views were less politically polarized (and also were more weakly correlated with their willingness to self-identify as an “environmentalist”). Most strikingly, political ideology, a variable that strongly predicts climate polarization in the United States, was substantially less predictive of the climate beliefs of non-Whites relative to Whites. This same pattern held across a range of related beliefs, including belief in the existence of climate change, perceptions of the scientific consensus, and support for mitigation efforts (regulating greenhouse gases). Thus, factors that strongly predict Whites’ opinions on climate change and shape the dominant narrative about the partisan gap—namely, political orientation and self-identifying as an environmentalist—are relatively weak predictors for minorities.

Similar effects have also been obtained for socioeconomic status, whereby lower income and lower educated individuals also show weaker polarization of climate change opinions, relative to those with higher incomes and education levels (see Pearson et al., 2017; for a review). These findings suggest that, consistent with their heightened awareness of environmental risks, the climate change attitudes and beliefs of racial and ethnic minorities and of members of other socioeconomically disadvantaged groups may be less partisan and less ideologically driven compared to those of Whites and members of socioeconomically advantaged groups.

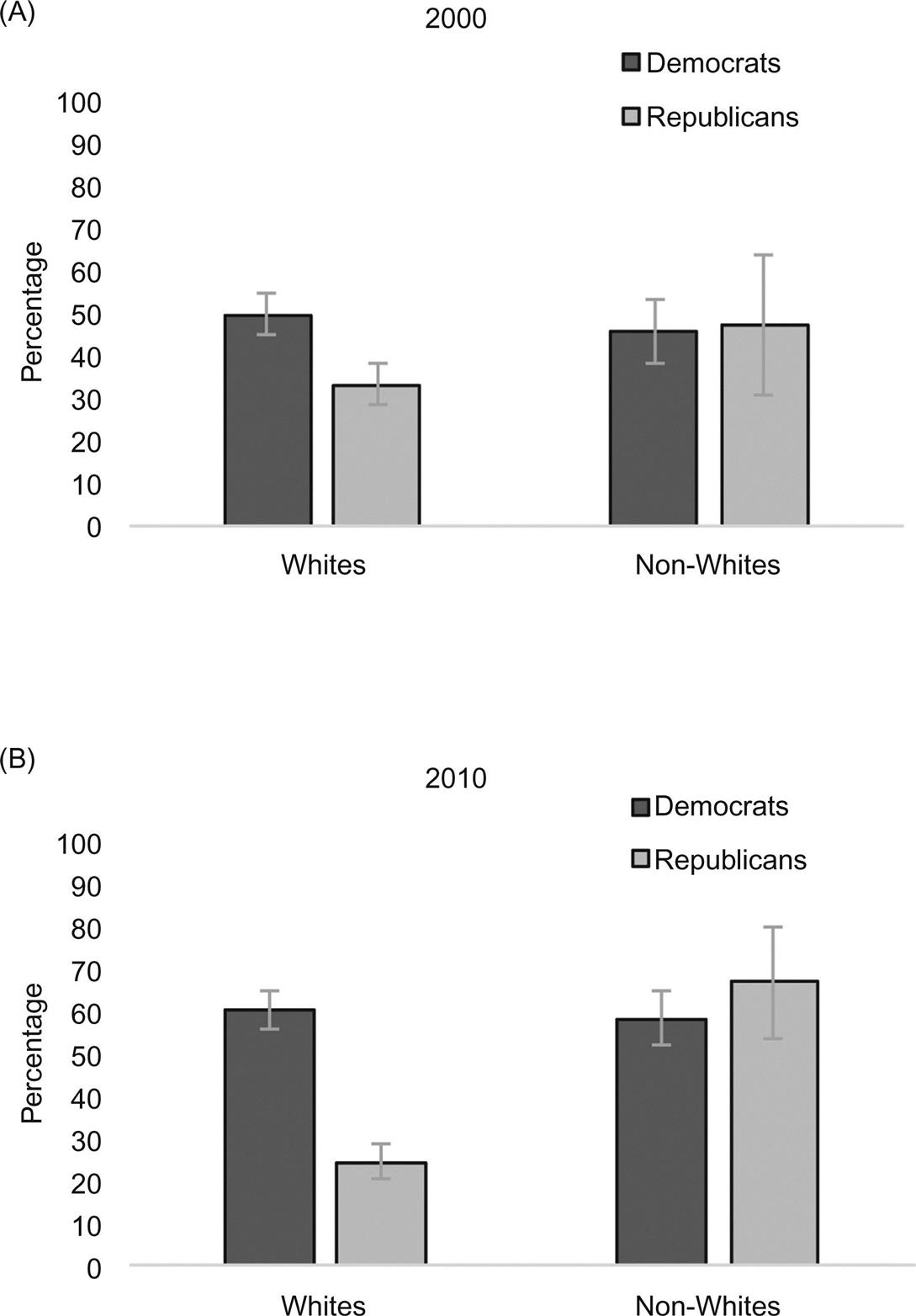

Notably, within the United States, there is also evidence of differential political polarization between advantaged and disadvantaged groups in the perceived dangers posed by climate change. Figs. 5.2 and 5.3 show the percentage of Whites vs non-White minorities and lower income vs higher income Americans, respectively, who indicated that the “rise in the world’s temperature” is “extremely” or “very” dangerous from the 2000 and 2010 GSS. As seen in the figures, the concerns of Whites and higher income Americans grew more politically polarized over this time period, in line with the familiar trend seen in public opinion research and commonly reported in news media on climate change (see Dunlap et al., 2016). In sharp contrast, the concerns of non-Whites and lower income respondents showed little evidence of political polarization in either 2000 or 2010. Similar trends have been documented for educational attainment in the United States, with increasing polarization of climate opinions among more educated Americans between 2001 and 2016 (see Dunlap et al., 2016).

Taken together, these findings suggest that advantaged and disadvantaged group members’ responses to climate change may be rooted in different motivations and concerns, with partisan perspectives and ideological concerns more strongly accounting for the responses of the former, and concerns about equity, health, and community impacts more strongly influencing the responses of the latter. Consistent with this perspective, Ehret, Sparks, and Sherman (2017) found that higher levels of education led to increased attention to and awareness of elite political cues (e.g., partisan news media, political candidate speeches), which was associated with the stronger adherence to partisan positions on climate change and the environment. In contrast, as previously noted, members of disadvantaged groups show greater awareness of the risks of climate change and their vulnerability to its impacts and indicate stronger support for climate policies as a consequence.

These findings have important implications for efforts to broaden public engagement on climate change. Groups for whom the issue of climate change is less politically charged, such as racial and ethnic minorities and members of socioeconomically disadvantaged groups, represent key audiences for bridging partisan disagreements and building policy consensus. Social psychological research suggests that intersectional or “dual identity” groups (e.g., non-White and lower income conservatives) are uniquely positioned to act as a communication gateway between groups that represent the respective sources of their dual identity and have the potential to garner trust from both groups. Levy, Saguy, van Zomeren, and Halperin (2017), for instance, found that the mere presence of a group with a dual identity (Israeli Arabs) can lead to reduced conflict and improved intergroup relations, even in high conflict settings. The presence of individuals with intersecting identities can also disrupt stereotypical and heuristic modes of thinking and can signal to oppositional groups that a common identity with shared perspectives, incorporating viewpoints of both groups, is possible (see Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000).

Strategic messaging that focuses on political disagreements at the expense of other concerns (e.g., disproportionate impacts of climate change, unequal access to green jobs) may be relatively ineffective for engaging members of disadvantaged groups, whose views on the issue may be less partisan-driven (Schuldt & Pearson, 2016). Researchers and practitioners would also be wise not to mistake some minority groups’ lower identification as “environmentalists”—a term that may signal other identity-relevant information, such as race or class membership (see the next section)—with a lack of concern about climate change or other environmental issues.

5.4.2 Stereotypic representations as barriers to engagement

Research on variability in disparities across different science and engineering fields may offer insights into factors that perpetuate environmental occupational disparities, as well as impede broader engagement with environmental organizations and professions more generally. A look at research on gender disparities in science and engineering is illustrative. In their comprehensive review, Cheryan et al. (2017) identify two key factors that reduce women’s sense of belonging and contribute to larger disparities (greater male representation) in engineering fields compared to math and the life sciences: stronger gender stereotypes (e.g., masculinity) associated with engineering, and limited early exposure to female role models in engineering compared to math and life sciences. Below, we examine evidence that each of these general factors—stereotypes and limited representation of role models—may undermine minority engagement within the environmental sector.

Public perceptions of scientists as white and male have remained largely unchanged within US society over the past half century (Steinke et al., 2007). However, recent findings suggest environmental STEM fields may face a dual burden, contending with both STEM and environment-specific stereotypes that may contribute to uniquely high disparities in environmental fields. In an online survey of US adults (Pearson & Schuldt, 2015), participants indicated the extent to which they associated the terms “environmentalist,” “scientist,” and “engineer” with each of four racial/ethnic groups: White/European Americans, Black/African-Americans, Latinos, and Asian Americans, using 7-point scales (1=not at all to 7=very much). Only the category White was rated significantly above the scale midpoint (4) for the term “environmentalist,” t (167)=9.74, P <.001, and Whites were more strongly associated with the term environmentalist compared to all other groups (all pairwise Ps <.001). All other non-White racial and ethnic categories were significantly below the scale midpoint [ts from −6.42 (vs Black/African-Americans) to −2.10 (Asian Americans), Ps <.04], indicating a dissociation between these groups and the term “environmentalist.” In contrast, Asian Americans were positively associated with the terms “scientist” and “engineer,” relative to the midpoint (ts > 5.45, Ps <.001), and Blacks were more strongly associated with these terms (albeit still below the scale midpoint) than with the term “environmentalist” (Ps <.01). Moreover, both White and non-White participants more strongly associated Whites with the term environmentalist than all other racial and ethnic groups (all paired-sample Ps <.001).

A recent nationally representative survey lends additional support for these findings and highlights the unique challenges facing environmental organizations and advocacy groups. In a representative survey of US adults conducted April–May of 2016, we (Pearson et al., 2017) found that both Whites and non-Whites strongly associated “environmentalists” with the racial category White. Moreover, both groups dissociated non-White minority groups (Blacks, Latinos, and Asians) with the category “environmentalists” relative to the midpoint of the scale. We also found strong consensus in class stereotypes related to income and education, such that the term “environmentalist” was associated with being moderately wealthy and highly educated. These class stereotypes were similarly widely shared and varied little by respondent race/ethnicity, income, or education level.

Theory and research suggest that stereotypes can operate as powerful cues to belonging, signaling whether a group or domain is compatible with one’s social identity. According to the identity-based motivation framework (IBM; Oyserman, Fryberg, & Yoder, 2007), people are particularly likely to engage in behaviors that are seen as congruent with their racial group identity (“ingroup-defining”) and to avoid behaviors that are seen as incongruent with their identity. Oyserman et al. (2007) found that lower income African-American and Latino youth perceive healthy eating and exercise as identity incongruent and consequently expressed lower motivation to engage in these behaviors when their racial/ethnic identity was made salient. Additional studies have directly linked stereotype accessibility to identity congruence. When African-Americans and Latinos were prompted to consider stereotypes about their ingroups as self-defining, they showed decreased preferences for healthy foods and increased preferences for unhealthy foods (Rivera, 2014). Thus, factors beyond awareness of climate change and its risks, such as stereotypic associations with the terms “environmentalist” and “environmentalism,” which may evoke concerns about the compatibility of one’s identity with those in environmental organizations, may also contribute to disparities in the environmental sector (see Jones, 2002; Mohai, 2003).

Race and class-based stereotypes may also extend to notions of the “environment” and “environmentalism” in ways that similarly impede public outreach efforts. For instance, the use of nonurban imagery and a common focus on the preservation of natural and uninhabited spaces in conservation advocacy may signal that the perspectives and concerns of nonrepresented groups—and particularly those in urban areas—are not valued. Indeed, studies of environmental media reveal a strikingly narrow range of imagery used to depict the environment in both online and print media. For instance, in their analysis of the first 400 Google image search results for the word “ecosystems,” Medin and Bang (2014) found that 393 (98.2%) did not include humans, 4 (1%) had humans within the ecosystem, and 3 (.8%) had humans outside looking in. Moreover, they found that European American (but not Native American) narratives in children’s books tend to position human beings as apart from nature, rather than as part of it. Such depictions may unwittingly alienate individuals for whom environmental issues are also urban issues with significant human dimensions.

Psychological research on stereotyping and identity threat can help guide the development of interventions to combat environmental stereotypes and their transmission. Low representation of minority groups in environmental organizations, and particularly among those in leadership roles, may perpetuate stereotypic beliefs about environmental groups as noninclusive and, in turn, undermine minorities’ identification with nondiverse environmental groups and their initiatives. In one experiment examining gender disparities in STEM (Murphy, Steele, & Gross, 2007), university students were shown one of two versions of a 7-min promotional video for an upcoming science and engineering leadership conference that depicted either a gender-balanced or a gender-unbalanced (3:1, male to female) ratio of attendees. Compared to those in the gender-balanced condition, women in the gender-unbalanced condition showed elevated stress and reported a lower sense of belonging and less interest in attending the conference. Thus, visible cues of low representation can reinforce notions that women do not belong in a stereotypically male-dominated domain. Nevertheless, stereotypic beliefs are malleable. In one experiment, simply reading a short (200-word) news article that computer scientists no longer fit the male stereotype significantly increased women’s career interests in computer science (Cheryan, Plaut, Handron, & Hudson, 2013; see also Cheryan, Plaut, Davies, & Steele, 2009). Similar studies testing the malleability of environmental stereotypes represent a promising avenue for future research.

Finally, early exposure to science through both formal (e.g., secondary education) and informal learning environments (e.g., news media, entertainment, museums) has been shown to predict professional engagement later in life. Access to field-specific coursework—a primary means through which people may be exposed to ingroup role models—has been shown to predict reduced gender disparities (Cheryan et al., 2017). Nevertheless, early exposure may also widen disparities if this exposure reinforces cultural stereotypes and undermines a sense of belonging for members of underrepresented groups. Thus, future research might examine how early experiences with both formal and informal environmental education and experiences may exacerbate or reduce existing disparities, as well as the stereotype processes that are presumed to mediate these disparities.

5.4.3 Perceptual barriers and norm-based messaging

Misperceptions of group norms related to Whites’ and non-Whites’ environmental engagement may also impede diversity efforts within the climate movement. Numerous studies document the power of social norms in guiding sustainability-related behavior (Miller & Prentice, 2016). Individuals are more likely to avoid littering, conserve energy, and save water when a majority of others in close proximity do the same (Nolan, Schultz, Cialdini, Goldstein, & Griskevicius, 2008). Moreover, normative influence can outweigh cost savings in driving conservation behavior. In one field experiment, making energy-conscious choices visible to others (a nonfinancial reputational incentive) was more effective at increasing participation in an energy blackout prevention program in California than a $25 monetary incentive, leading to over four times the rate of compliance (Yoeli, Hoffman, Rand, & Nowak, 2013).

Work on identity threat and IBM suggests that minority group members may be particularly sensitive to norms that signal what behaviors are appropriate and preferred by their group (Oyserman & Lewis, 2017; Oyserman et al., 2007). When behaviors are believed to be normative (i.e., what “people like me” do), minority individuals are more likely to engage in personal, political, and social causes (Oyserman et al., 2007). In the absence of such normative information, people may look to the visible representations of their group in organizations and decision-making (e.g., the group memberships of those in leadership roles within the environmental sector; Taylor, 2014). Moreover, research suggests that norm conformity can occur even when the perceived norm is stigmatizing for members of a particular social group, and when members of the stigmatized group are motivated to avoid conforming. For instance, in a field experiment in rural India, Hoff and Pandey (2006) provided unacquainted schoolchildren with a monetary incentive to solve as many simple puzzles as possible out of a set of 15. In one version of the experiment, children’s caste membership was made public before completing the puzzle task. When the participants’ caste was publicly known, the motivation and performance of lower caste students (but not of other students) declined markedly compared to a condition in which the caste was unknown, consistent with the low achievement stereotype of lower caste groups. Thus, when individuals are identified as members of a stigmatized group, they may respond behaviorally by conforming to stereotypic beliefs, even when they are motivated to avoid doing so (e.g., when counterstereotypic actions are incentivized).

Given the positive connotations associated with proenvironmentalism (Steg & Vlek, 2009), being perceived as a member of a group that is relatively unconcerned about the environment (compared to other groups) may be similarly stigmatizing and, to the extent that these perceptions are internalized among minority group, may impede engagement among groups that are negatively stereotyped within the environmental sphere (e.g., non-Whites and those with lower income and education levels). We explore these normative influence processes below.

Despite evidence that salient group norms can shape behavior, few studies have investigated whether perceptions of attitudinal and behavioral ingroup norms around environmentalism (e.g., which groups are most concerned about climate change) vary among different racial and ethnic groups. Negative consequences of misperceiving ingroup norms, such as holding the belief that one’s private views deviate from the consensus views of one’s group (i.e., “pluralistic ignorance;” Prentice & Miller, 1993)—are well-documented. These include attitudinal and behavioral conformity to the perceived ingroup norm (Botvin, Botvin, Baker, Dusenbury, & Goldberg, 1992; Prentice & Miller, 2003), feelings of alienation and disidentification with a particular domain (Prentice & Miller, 1993), and reduced willingness to share opinions about contentious topics. Research investigating pluralistic ignorance in the context of climate change has documented self-silencing among those most concerned about the issue (Geiger & Swim, 2016), and recent survey findings suggest that self-silencing in discussions around climate change may be particularly common among non-Whites: In a nationally representative sample, whereas 53% of Whites reported being willing to admit differing viewpoints about climate change in discussions with family and friends, only 26% of Blacks and 34% of Latinos report a similar willingness to do so (Speiser & Krygsman, 2014). Thus, documenting the nature and extent of pluralistic ignorance in the context of climate change among racial and ethnic minority groups remains a critical avenue for future research.

Initial evidence for the importance of perceived ingroup norms in non-Whites’ climate change engagement was obtained in a study with a racially and socioeconomically diverse online sample of US adults (Pearson et al., 2017)2. In this study, ingroup pluralistic ignorance about climate change (operationalized as self-minus perceived racial/ethnic ingroup concern, controlling for mean levels of self-concern) was assessed, along with perceived individual and collective efficacy about climate change and environmental citizenship (social, economic, and political engagement with environmental organizations and initiatives). Environmental efficacy (Ojala, 2012) included items assessing individual efficacy (e.g., “I think that I myself can contribute to the improvement of the climate change situation”) and collective efficacy (e.g., “I believe that together we can do something about the climate threat”), rated on a scale from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree). Environmental citizenship (Stern, Dietz, Abel, Guagnano, & Kalof, 1999) included summed yes/no responses to seven questions (e.g., “In the last twelve months, have you read any newsletters, magazines or other publications written by environmental groups?”; “Boycotted or avoided buying the products of a company because you felt that company was harming the environment?”; “Voted for a candidate in an election at least in part because he or she was in favor of strong environmental protection?”).

When controlling for political ideology, across all respondent groups, a greater perceived gap between self and ingroup concern predicted lower efficacy beliefs about climate change (beta=−.15, P=.006), and lower environmental citizenship (beta=−.26, P <.001), with stronger effects shown for racial and ethnic minority respondents. Moreover, when self and perceived ingroup concern about climate change were included simultaneously in regression analyses that included the same covariates, perceived ingroup concern about climate change predicted Asian (beta=.32, P=.03), Black (beta=.23, P=.02), and Hispanic (beta=.27, P=.02) respondents’ environmental citizenship and was the sole significant predictor of Hispanics’ and Asians’ citizenship, in contrast, among Whites, only self-reported concern predicted. Whites’ environmental citizenship (beta=.28, P=.01). Moreover, these effects could not be explained by differences in intergroup attitudes (Wolsko, Park, & Judd, 2006), political ideology (liberalism–conservatism), or socially desirable responding (Dunton & Fazio, 1997), and remained significant when these variables were included as covariates in the models.

These findings suggest that perceived ingroup attitudinal norms about climate change may shape non-Whites’ perceptions of individual and collective efficacy around climate change and undermine their engagement with environmental organizations and initiatives. Norms-based interventions appear especially promising for motivating environmental engagement among individuals from more collectivistic cultures, such as individuals from East Asian countries and US Hispanics and Latinos. For instance, Eom, Kim, Sherman, and Ishii (2016) found that whereas environmental concern predicted proenvironmental consumer choices among European Americans but not Japanese, perceived ingroup norms were the stronger predictor among Japanese. Thus, future studies should also consider the broader cultural orientations of different demographic groups in assessing the potential effectiveness of norm-based messaging in environmental outreach and advocacy work.

5.5 Implications for organizational outreach and policy

The research reviewed in the previous section suggests that the lack of diversity in the environmental domain may be rooted, in part, in different motivational barriers that exist across majority and minority groups. These differing motivations, in turn, may be shaped by persistent and pervasive racial, ethnic, and class stereotypes and differing levels of visible representation in the environmental sector among majority and minority groups. Recognition of these barriers affords new pathways for interventions. For instance, messages that accurately reflect the high levels of concern among non-White and lower income groups and key contributions of people of color, and especially those within leadership roles (see Green 2.0’s “Leadership at Work” initiative for a notable example), may be particularly effective for engaging groups that remain underrepresented in environmental discourse and decision-making.

5.5.1 Diversity messaging to promote inclusion

Within organizations, “colorblind” messaging that focuses on member similarities and avoids issues of race and ethnicity can signal that these identities are not valued and, in turn, can fuel distrust of these organizations, particularly when they have low diversity. In a series of experiments, Purdie-Vaughns, Steele, Davies, Ditlmann, and Crosby (2008) showed Black professionals corporate brochures that depicted either many or few minority staff-members, coupled with an organizational mission statement emphasizing colorblindness or one emphasizing the value of diversity. Participants were then asked for their opinions about the organization. Those exposed to a colorblind message, when that message was also coupled with images depicting low minority representation, were less comfortable envisioning themselves as an employee, less trusting of the organization’s management, and more concerned about how others in the organization would treat them.

Whites’ attempts to be colorblind can alienate minorities, who generally seek acknowledgement of their racial identity, and fuel interracial distrust. For instance, Apfelbaum, Sommers, and Norton (2008) found that although avoidance of race in conversations was seen by Whites as a favorable strategy for promoting positive interracial interactions, in practice, the failure to acknowledge race in conversations, when relevant, resulted in greater perceptions of racial prejudice by Black interaction partners. Moreover, racial colorblindness extends to perceptions of environmental impacts and government responses to those impacts. For instance, whereas a large majority (71%) of African-American respondents attributed the disproportionate effects of Hurricane Katrina on minority communities to the persistence of racial inequality in the United States, only 32% of Whites believed the same (Doherty, 2015). Similarly, whereas two-thirds (66%) of African-Americans indicated that the government’s response to Hurricane Katrina would have been faster if most of the victims had been Whites, just 17% of Whites agreed.

These findings highlight a problem for environmental organizations that seek to diversify their memberships or broaden their appeal, but fail to sufficiently address disparities in environmental impacts or the potentially differing needs and concerns of underrepresented communities. By contrast, multicultural organizational practices, which seek to acknowledge both differences as well as shared perspectives among members and prospective members, can foster mutual understanding and promote a sense of belonging among members of historically marginalized groups. At the same time, messaging that emphasizes differences alone can be viewed as coercive. Tailored inclusion that highlights the dual identities of minority groups, connecting subgroup identities with broader American society, may be a more effective approach when developing inclusive messaging for advocacy and community outreach (see Lewis & Oyserman, 2016). At present, limited research has examined messaging on diversity in the context of environmental issues - a critical avenue for future psychological scholarship.

5.5.2 Bridging science and practice: Insights from public health

Psychologists are uniquely positioned to develop behavioral interventions that are “wise” to both the social contexts and underlying psychological processes that shape adaptation and mitigation behavior (see Walton, 2014; Clayton et al., 2015). To maximize their impact, behavioral interventions need to be appropriately tailored for different audiences and sensitive to their social context, and to set in motion new thought processes or behaviors that can be sustained over time (Cohen et al., 2017; Cunningham & Card, 2014). In developing these interventions, scholars and practitioners may benefit from incorporating insights from evidence-based approaches that have seen real-world success outside of the domain of climate change.

For instance, like the problem of climate change, the HIV/AIDS epidemic is global in reach, has both biophysical and social causes, and disproportionately affects communities of color and other socioeconomically disadvantaged groups (Pellowski, Kalichman, Matthews, & Adler, 2013). Research on health disparities related to the HIV epidemic highlights not only ways in which risks can be effectively communicated to different segments of the public but also ways that organizations can involve at-risk groups in decision-making processes that can influence public policy. Through initiatives such as the “Face of AIDS” and the “Global Village” that emphasize social dimensions of the epidemic, the International AIDS Conference—a global forum of scientists, practitioners, and communities directly affected by HIV—has successfully pressured governments and corporations to seek universal global access to preventive treatments and to collaborate in developing evidence-based solutions (Brecher & Fisher, 2013).

Psychological research on health disparities also offers a powerful blueprint for understanding how to design, evaluate, and effectively disseminate interventions to effect behavior change that may prove useful for combating climate change (e.g., reducing energy use; Swim, Geiger, & Zawadzki, 2014) and helping communities adapt to its impacts. For example, research suggests that highlighting “healthy” in the domain of food consumption can backfire, making healthy food less identity congruent for minority groups (Gomez & Torelli, 2015). Similarly, emphasizing protection of the natural environment (e.g., nonurban spaces) in the context of climate change may undermine the identity-congruence of climate actions among historically marginalized groups who may view the issue primarily through the lens of public health, economics, and community engagement (see Bullard et al., 2011). Practically, initiatives such as the US Center for Disease Control’s High Impact HIV/AIDS Prevention Project and Prevention Research Synthesis (PRS) Project provide working models for the effective delivery of behavioral interventions to mitigate health risks among disproportionately affected groups that might be productively translated to the climate context. The PRS includes an online compendium of nearly 100 evidence-based behavioral interventions and best practices, with intervention materials packaged into user-friendly kits that are freely accessible to state and local governments (effectiveinterventions.org; see Norton, Amico, Cornman, Fisher, & Fisher, 2009). Presently, no similar programs exist for evaluating and broadly disseminating climate-related behavioral interventions to different segments of the public—an important direction for future psychological research (see Brecher & Fisher, 2013).

5.6 Conclusion

As this chapter and the others in this volume make clear, climate change is not only a formidable technical challenge but also a complex social challenge that will require multifaceted social solutions. We have focused on the opportunities afforded by adopting a diversity science approach to climate change, one that leverages the extensive literature on group processes within social and organizational psychology, to explore how social identities impact environmental engagement, including on the issue of climate change. Although racial and ethnic disparities within the environmental movement are well-documented (see Taylor, 2014), the approach we describe here highlights key psychological processes (e.g., differing group motives, stereotypic representations, and normative perceptions) that may contribute to these disparities and impede efforts to broaden public engagement on climate change. Importantly, these processes also point to promising pathways for future research and intervention.

Our hope is that this approach offers a blueprint of the types of diversity-related questions that may be examined from the perspective of social psychological research and theory. For example, what types of messages are best for changing misconceptions about low minority concern? What kinds of media are most effective for enhancing environmental advocacy and professional engagement among underrepresented minority groups? Moreover, our review focused primarily on racial and ethnic disparities; however, identity-based approaches may be similarly fruitful for understanding a broader range of identity factors, such as gender and religious identities, which have also been shown to predict how people perceive and respond to climate change and organizations working to address it (e.g., Pearson et al., 2017).

The differential impacts of climate change pose a unique challenge for motivating sustained collective action on the issue. Collective threats can enhance the salience of shared aspects of identity in ways that motivate cooperation (Dovidio et al., 2004). Nevertheless, cooperation can be difficult to sustain over time, and particularly in the face of inequities that highlight group differences (Aquino, Steisel, & Kay, 1992; also Piff, Kraus, Côté, Cheng. & Keltner, 2010). Identifying the conditions under which people form and maintain shared identities around threats that expose and exacerbate societal inequities is thus a critical question for future research. Moreover, few studies have examined which identity dimensions (e.g., perceived similarity vs group investment; see Masson & Fritsche, 2014) matter for climate engagement, or examined causal effects of identity on climate risk perceptions—another important area for psychological inquiry.

Research on social disparities in the context of climate change has the potential not only to inform policy but also yield new insights about group processes. For example, understanding racial/ethnic and class disparities in environmental STEM may inform our understanding of factors contributing to heterogeneity in disparities, generally, across STEM fields—an emerging direction for STEM diversity research (see Cheryan et al., 2017). More generally, the context of climate change provides an opportunity to examine how stereotyping and identity processes shape self-perceptions and collective action within a politicized and moralized domain (Steg & Vlek, 2009).

Finally, the global reach of climate change highlights an urgent need for research beyond the United States and other industrialized nations to examine how group dynamics influence climate change understanding and action in regions that shoulder a disproportionate burden of climate impacts. Despite the need for international cooperation and consensus-building, cross-national empirical research on racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic diversity is currently lacking (see Pearson et al., 2017). Moreover, few studies have explored ways in which nonpartisan identities, such as race/ethnicity and social class, may interact to influence climate change engagement. In addition to highlighting the importance of considering justice and equity motives in environmental decision-making, our review suggests that racial and ethnic minorities and members of other disadvantaged and disproportionately-affected groups represent critical audiences for bridging growing partisan disagreements on climate change. Increasing attention to these factors, and the role of diversity more generally in climate change communication and public advocacy, can enhance understanding of key barriers to participation in climate discourse and decision-making and help pave the way for a more inclusive and influential climate movement for the 21st century.