Individual impacts and resilience

Thomas J. Doherty, Sustainable Self, LLC, Portland, OR, United States

Abstract

This chapter provides an overview of the individual psychological impacts of climate change in their direct, indirect, and vicarious forms. The role of cultural values and ideals of social and environment justice are highlighted as these provide the lenses through which many people around the world understand how climate change affects them. A distinction is made between climate effects on mental health, such as trauma in the wake of disasters, and effects on psychological flourishing as the burden of climate change jeopardizes people’s ability to enjoy positive emotions and trust in the future. Healthy coping responses to climate change range along a spectrum from the bare survival of individuals and communities to optimum health and thriving in the context of one’s culture and values. Among individuals affected by climate change, there are potentials for resiliency, healing, and posttraumatic growth. Adjusting to climate change requires a combination of realistic goal setting; building one’s capacity for engagement though positive imagery and self-restoration; and a commitment to education about climate change, making responsible lifestyle choices, and promoting political and structural changes in society.

Keywords

Global climate change; mental health; flourishing; environmental justice; depression; anxiety; adjustment; psychiatric diagnosis; coping; resilience

Among the greatest challenges of the unfolding problem of global climate change is marshalling the best of our intellectual and creative resources to engage with the enormity of the issues involved while also being conscious and expressive of our emotional reactions. Nowhere is the tension between the intellectual and the emotional aspects of climate change, between head and heart, more salient than at the individual level of human functioning: How people make sense of climate change on a personal level and how they deal with the psychological effects of climate change.

The scope of this chapter includes an overview of individual psychological impacts of climate change in their direct, indirect, and vicarious forms. The chapter highlights the importance of cultural values and ideals of social and environment justice; these provide the lenses through which many people around the world understand how and why climate change issues affect them. When envisioning psychological impacts of climate change, a conceptual distinction is made between adverse effects on mental health, such as the trauma or psychiatric symptoms in the wake of disasters, and adverse effects on flourishing as the burden of climate change jeopardizes people’s ability to enjoy positive emotions and to trust in the future. This distinction is important as climate change affects both facets of human psychological functioning.

Moving beyond an understanding of psychological impacts to identify the most effective long-term strategies and techniques for coping with climate change is important task for future research and practice. The chapter describes how healthy coping responses to climate change range along a spectrum from the bare survival of individuals and communities to thriving and optimum health in the context of one’s culture and values. Under the broad umbrella of psychological coping, there are potentials for resiliency, healing, and posttraumatic growth among individuals affected by climate change. The chapter proposes using a systems perspective as a framework that allows for understanding both (1) the ways that global scale climate issues affect individual people at the local level and (2) how to rationalize the benefits of individuals taking personal actions to positively address climate issues at larger scales. Adjusting to climate change with integrity and resilience will require a combination of realistic goal setting, building one’s capacity for engagement though positive imagery and self-restoration, and commitment to long-term actions and goals including continuing education about climate change, making responsible lifestyle choices, and promoting political and structural changes in society.

There are several takeaways from this chapter:

- • It is a difficult to thoroughly describe the mental health impacts of climate change as they occur at multiple scales of place and time, and are viewed through diverse cultural lens. Some psychological effects, such as anxiety or despair about the traumas, injustices, and extinctions associated with climate change, are experienced at a distance from disaster events.

- • There is an urgent need to address the impacts of climate change disaster events on mental health. But, it is also important not to be limited by a disaster framework. The psychological impacts of climate change can also be chronic and gradual, driven by changes in economic well-being and losses to quality of life. Also, individuals buffered from the effects of disasters due to their region or relative wealth can still experience mental health impacts.

- • The mental health impacts of climate change, even in the same geographic location, will differ between privileged and nonprivileged individuals, among genders, and between those of different cultures and values. Intersectionality and environmental justice frameworks can illuminate the unique impacts experienced by individuals across the socio-cultural spectrum.

- • The mental health impacts of climate change are influenced both by a person’s psychological vulnerabilities and by the severity of the climate change impact they endure. For example, individuals with psychiatric issues (e.g., tendency toward anxiety, substance abuse or major mental illness) will be at higher risk for trauma associated with climate change. However, even among the most healthy and resilient individuals, severe disruptions due to climate change can cause mental health problems.

- • The presence of pro-environmental values and environmental connectedness have both positive and negative influences on climate change impacts and coping. Individuals with strong environmental or social ethics, or a personal sense of connectedness to nature and other species, are at more risk for distress associated with climate change. However, environmental values and connections also promote action regarding climate change and a tendency toward health restoring and stress reducing nature-based recreation activities that buffer impacts.

- • There is no one way to cope with climate change. When taking the perspectives of individuals around the globe, coping can range from basic survival, to maintaining a culturally intact community and way of life, to fostering one’s personal growth and flourishing given the reality of climate change and its moral and practical dilemmas.

- • An upside to the systemic nature of climate is that there are many ways to engage with the problems associated with climate change, and it is possible to intervene at multiple scales (i.e., at personal, community, or international levels) depending on one’s goals and resources. Making progress on any subset of issues, such as alleviating poverty or disparities in one area, can contribute to system-wide improvements.

- • Activities that address climate change and reducing one’s carbon footprint (e.g., active commuting; practicing nonmaterialistic lifestyles, and creating urban greenspaces) also promote good health. Overall, addressing climate change is good for people’s mental health.

10.1 How climate change impacts mental health: Three pathways

How can a planet-wide process like anthropogenic climate change influence people’s mental health and well-being at the individual level? Simply put, climate change combines with other issues to create an ongoing, global health crisis. For example, changes in climate and local weather have synergistic interactions with poverty, discrimination, population pressures, competition for resources, and environmental problems. This makes impacts quite severe for some individuals, to the point of complete disruption of their lives and communities. Conversely, those who are geographically protected from negative effects, have resources to adapt to climate-related issues, or who have a sense of control over climate-related actions or policies are likely to experience fewer stressors, and, at least in the short term, may have their lives be largely unaffected.

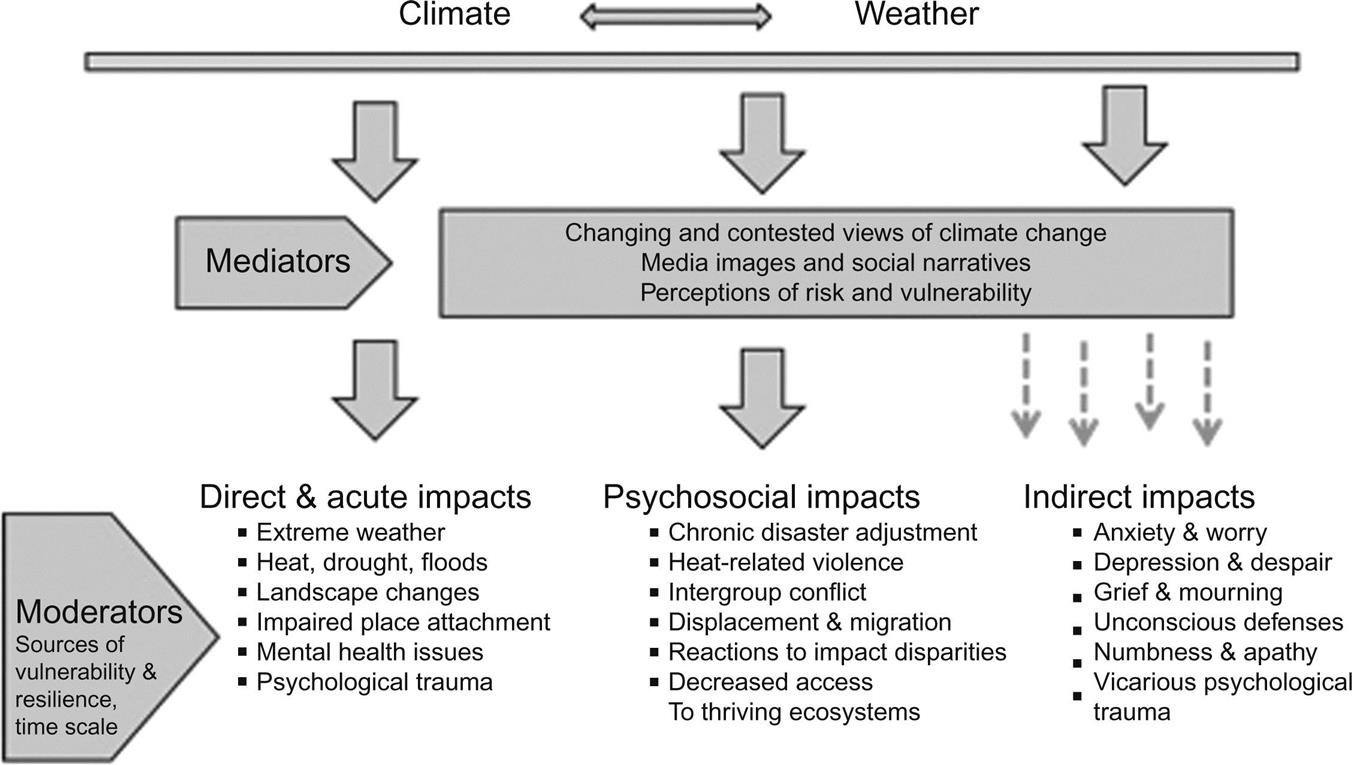

While the potential for individual mental health impacts of climate change is highly varied, it is possible to identify general principles that predict psychological impacts and buffers. We can generalize that, at the individual level, climate change will affect mental health through:

There is also the potential for mental health impacts to be mixed (e.g., a person or community experiencing acute issues and chronic climate stressors). And, it is also helpful to characterize impacts as simple or complex in terms of their severity and the presence of compounding problems. For example, a resilient individual or community may cope with a single, discrete stressor such as the need for relocation due to erosion or rising sea levels. Alternatively, an individual or community may be hampered by a complex burden of pre-existing mental health issues, chronic environmental stressors, and limited resources from which to draw from.

Direct impacts: The causal pathways of the direct mental health impacts of climate change are relatively clear. Geophysical effects of climate change include flooding in coastal cities and inland cities near large rivers, hotter and drier weather associated with heat waves, increased wildfire, and stresses to fresh water supplies, and in northern regions, recession of sea ice causing increased erosion and threatening communities with relocation. Issues like severe weather events, poorer air quality, degraded food and water systems, and climate-related illnesses all impact individual health and increase the prevalence and severity of mental disorders (USGCRP, 2016). These issues also place increased demand on mental healthcare services in affected communities. In impoverished or marginalized communities, this added stress can overwhelm already compromised healthcare infrastructure (see review in Dodgen, et al., 2016, and discussion in Doherty, 2015a).

Some mental health injuries from natural and technological disasters associated with climate change are immediate. Climate disasters have a high potential for psychological trauma from personal injury, injury or death of loved ones and pets, damage or loss of home and possessions, and disruption or loss of community systems and livelihood. In disaster situations, pre-existing issues such as depression, family problems, psychiatric disorders, and alcohol and substance abuse can also be made more serious (see WHO: Impact of emergencies http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs383/en/). Other disaster effects unfold more gradually because of changing temperatures, rising sea levels, and impacts on social infrastructure and food systems. (For reviews of direct psychological impacts see Chapter 9: Threats to mental health and wellbeing associated with climate change; Berry, Bowen & Kjellstrom, 2010; Clayton, Manning, Krygsman & Speiser, 2017; Doherty, 2015b; Gifford & Gifford, 2016; Satcher, Friel & Bell, 2007) (Fig. 10.1).

Indirect impacts: Climate disasters and acute environmental disruptions cause indirect impacts as these long-term and chronic disruptions manifest on the level of economics and societal infrastructures. For example, lingering droughts can impact people’s livelihood, create food insecurity, exacerbate community divisions, and lead to forced relocation, refugee status and land-use conflicts (Hatfield, et al., 2014; Devine-Wright, 2013; Hsiang, Burke & Miguel, 2013; Fritze et al., 2008). All these issues impact mental health.

Social issues that arise or become more severe after disasters include economic problems, crime, and discrimination against marginalized groups. There can also be problems or side-effects created by humanitarian responses to disasters including overcrowding and lack of privacy in refugee camps, loss of community agency and traditional supports, and anxiety due to a lack of information about food distribution or how to obtain other basic services.

In many cases, acute disaster level impacts of climate change cascade into cultural level upheavals that promote a sense of dislocation, meaninglessness, or despair among affected individuals and their social groups (Silver & Grek-Martin, 2015; Adger, Barnett, Brown, Marshall & O’Brien, 2013). For example, the origins of the civil war in Syria and its resulting European refugee crisis are seen as being exacerbated by climate issues including a several year drought that contributed to crop failures, hunger, and social conflicts (Kelley, Mohtadi, Cane, Seager & Kushnir, 2015). Cultural level impacts of climate change may be most salient in indigenous, land-based cultures of the far North (Cunsolo Willox et al., 2012; Durkalec, Furgal, Skinner & Sheldon, 2015). However, cultural impacts can also occur among individuals in developed nations who are experiencing chronic climate-related issues such as droughts, wildfires, or flooding (e.g., Morrissey & Reser, 2007; Tapsell & Tunstall, 2008).

Vicarious impacts: The most widespread and difficult to measure mental health effects of climate change are those that occur outside of a short-term or localized disaster frame. Vicarious mental health impacts occur as those distant or buffered from direct and indirect climate stressors experience psychological distress or trauma. Even in the absence of disaster impacts, people may still experience distress about climate change including worry, anxiety, and despair (Moser, 2013; Searle & Gow, 2010; Verplanken, & Roy 2013). In the United States, approximately half of people surveyed have reported feeling disgusted, helpless, or sad about climate change. About 35% report feeling angry or afraid, and 25% report feeling depressed or guilty. Americans characterized as Alarmed (16%) or Concerned (27%) are much more likely to report being convinced of the danger of climate change and to feel sad, disgusted, angry, or afraid (Leiserowitz, et al., 2014). Some individuals equate their climate concerns with other experiences of trauma or victimization (Simmons, 2016). Distress about climate issues can also manifest as a subtle sense of disconnection from local places or from a sense of ecological or planetary wholeness (Albrecht, 2011).

There are several mechanisms for vicarious mental health impacts. Rapid changes in technology, population, global conflicts, and environmental problems can create a sense of crisis among individuals, particularly given instantaneous news and information technologies (Stokols, Misra, Runnerstrom & Hipp, 2009). Vicarious traumatization regarding climate issues is more likely in those who are personally exposed to climate change stressors (e.g., disaster professionals, healthcare providers, and journalists) (Palm, Polusny & Follette, 2004). The potential for vicarious posttraumatic stress disorders is reflected in current psychiatric literature (Jones & Cureton, 2014). In general, traumatic stress is amplified by rapid, enhanced and visceral media experiences of disasters, and terror events (e.g., Ahern, Galea & Resnick, 2002; Schuster, Stein, Jaycox, Collins, Marshall, Elliott, et al., 2001). From a sociological perspective, impacts from climate change and global issues such as famine, war, or species extinction can be perceived as “distant suffering” (see Boltanski, 2009). The process of bearing witness to these issues from a place of safety or privilege can prompt moral and ethical dilemmas in some individuals.

10.2 Cultural diversity, intersectionality and climate justice

From a global, multicultural perceptive, there are multiple truths about the impacts of climate change. When individuals around the world talk about “impacts” they refer to many separate, interrelated issues. Climate change can be understood from the perspective of physics and geophysical changes in the land and seas; from the perspective of changing regional weather and temperatures; from the perspective of human or environmental disasters related to abrupt climactic changes; and from a social and political perspective on contentious and often stalemated responses to climate change among nations. These perspectives become frames through which the people understand what affects themselves and their families and communities, and in turn through which we can understand people’s responses to these impacts. For example, climate change takes on certain meanings when considered from the perspective of a citizen of the “Global South” (e.g., Ghosh, 2017) who might view climate change effects in their region (e.g., on the Indian subcontinent) through a broader cultural and political context that includes a history of European colonialism and more recent effects of globalization and uneven economic and technological progress.

The feminist social science perspective of intersectionality (see Rosenthal, 2016) is helpful in identifying individual climate change impacts, because it highlights the relationship between structural and societal-level oppression and discrimination against individuals based on attributes such as gender and race. In this frame, mental health impacts of climate change are seen to intersect with individuals’ identity and power, as well as the inequities and stigmas they face. For examples, consider climate impacts experienced globally by low income women of color such as increased burdens of obtaining fresh drinking water in chronic drought conditions (see Terry, 2009) and by workers and laborers in areas prone to excessive heat such as Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent (see Berry et al., 2010).

Closely related to an intersectionality frame, an environmental justice or “Just Sustainability” perspective highlights the increased vulnerability of socially marginalized groups to environmental stressors such as those caused by climate change (Agyeman, Bullard & Evans, 2003). Notions of justice and fairness are present across the spectrum of climate change issues, for example, how communities safeguard the elderly or infirm during heat waves, how regional authorities adequately disperse water and aid supplies in drought affected areas, or how government funds are used for disaster response and rebuilding efforts. An environmental justice perspective involves individuals’ access to legal frameworks and tools to seek redress or compensation for environmental harms, fairness in distribution of resources, or benefits, participation in decision-making, and ethical protections for those least vulnerable. When these conditions are threatened or absent, individuals and communities will experience a lack of climate justice (see Hurlbert, 2015).

10.3 Climate change: Vulnerability and risk factors for mental health impacts

Understanding how an individual will respond to climate change is contingent on the severity of the climate impact or stressor they experience and its time frame (i.e., sudden or chronic) and on personal and contextual factors such their age, wealth and pre-existing physical and mental health; individual and cultural differences; as well as their understanding of climate change, environmental values, social influences, and community resources (Doherty, 2015a). For example, buffers to climate disaster impacts include a privileged social position, ability to travel or relocate, and access to educational and economic opportunities. Individuals with psychiatric issues (e.g., tendency toward anxiety, substance abuse, or major mental illness) will be at higher risk for trauma associated with climate change. The most vulnerable populations include people living in disaster-prone areas, indigenous communities, some communities of color, occupational groups with direct climate change, or disaster exposure (e.g., field workers, emergency first responders), those with existing disabilities or chronic illness, and older adults, women, and children (Gamble, et al., 2016). From an environmental justice perspective, people of color are often more vulnerable to the health-related impacts of climate change given their geographic placement and socioeconomic and demographic inequalities, such as income and education level (Grineski, et al., 2012; Parks & Roberts, 2006). Individuals from indigenous cultures are at risk for health impacts as well as additional impacts as climate changes disrupt traditional place-based lifeways (Durkalec et al., 2015; Maldonado, Colombi & Pandya, 2013).

Psychiatric risk factors: Even the most healthy and resilient persons may develop fatigue, strain, anxiety, and mood or behavioral problems when subjected to extreme stressors such as those associated with climate-related disasters. In disasters, mental reactions may also be superimposed upon pre-existing anxiety, mood, or psychotic disorders or upon brain or other physical injuries. Trauma-related psychological disorders are associated with risk and protective factors. For example, pre-trauma risk factors include prior mental disorders, environmental or socioeconomic stressors, and younger age at the time of exposure, while pre-trauma protective factors include social support and optimistic coping strategies. Risk factors during a disaster include personal injury or experiencing the death or injury of a loved one. Post-disaster risk factors include negative thoughts, unhealthy coping strategies, exposure to upsetting reminders, subsequent adverse life events, and financial or other trauma-related losses (Haskett, Scott, Nears, & Grimmett, 2008; Neria & Shultz, 2012).

Children: For children, direct and indirect disaster impacts can cause changes in behavior, development, memory, executive function, decision-making, and scholastic achievement (Somasundaram & van de Put, 2006). Direct experience of natural disasters can cause anxiety, nightmares, phobic behavior, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms, with the potential for physical-focused symptoms such as stomachaches among younger children (see Haase, 2017; Somasundaram & van de Put, 2006). In terms of the vicarious impacts of living in a climate-changed world, for both children and adolescents, problem-focused coping is associated with more worry more about climate change, while meaning-focused coping is positively related to well-being and optimism (Ojala, 2012, 2013).

Risks among educated and environmentally aware individuals: The presence of pro-environmental values and environmental connectedness have both positive and negative influences on climate change impacts and coping. Among many cultures, there are individuals or groups who see their identity as connected to nature, other species and natural processes (see Clayton, 2003). For those who consider the rights and well-being of other peoples, the natural world and other species to be in their scope of concern and ethical responsibility, climate change is a threat to identity and moral values. Education and awareness alone can increase the risk of distress regarding global climate change. Studies of environmental activists show that there is often a multidirectional relationship between one’s accumulated knowledge, their empowerment to act, and their ability to notice and experience environmental problems (Kempton & Holland, 2003). Some individuals learn about climate change in an abstract way and then become more sensitive and aware of local climate impacts. Alternatively, individuals may be thrust into action due to experience of local climate impacts which then leads them to further understand the nature and scope of climate change worldwide.

10.4 Mental health disorders associated with global climate change

In terms of psychiatric diagnosis, the mental health impacts of climate change will manifest as (1) trauma or stressor-related disorders, (2) anxiety and depression, (3) substance use disorders, (4) increased severity or complications of existing disorders or mental health issues, (5) short-term or chronic adjustment disorders, and (6) psychosocial problems such as family or occupational issues (see discussion in Doherty, 2015b). An early meta-analysis of studies on the relationship between disasters and mental health impacts found that between 7% and 40% of all subjects in 36 studies showed some form of psychopathology. General anxiety was the type of psychopathology with the highest prevalence rate, followed by phobic, somatic, and alcohol impairment, and then depression and drug impairment, which were all elevated relative to prevalence in the general population (Rubonis & Bickman, 1991).

Given the variety and multiple scales of climate change impacts, and the possibility of vicarious stress or traumatization, the potential for diagnosable climate change-related mental health disorders is high. In many cases, issues like disasters or significant environmental stressors will be the proximal cause of the disorder. In the case of individuals who are buffered from direct impacts but experiencing vicarious stress and trauma, diagnosis will likely also be associated with more compounding psychological stressors such as occupational or relationship issues. In all cases, accurate psychiatric diagnosis requires clinical judgment based on a person’s history and their cultural norms for expression of distress in the context of loss.

Trauma disorders: Consequences of climate-related disasters can include short-term acute stress disorder (lasting 3 days to 1 month) as well as posttraumatic stress disorder, characterized by significant impairment, intrusive memories, negative mood, dissociation, avoidance, and heightened arousal (manifested as sleep disturbance, irritable behavior, and/or hypervigilance). Based on current guidelines, formal diagnosis requires that a person has experienced a traumatic event, has witnessed it occurring to family members or friends, or has had repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of events (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Traumatic exposure via electronic media is considered a diagnostic criterion if the exposure occurred in a work setting, such as among hospital or emergency services professionals. Notably, vicarious posttraumatic symptoms have also been observed in the public among those exposed to repeated media images of traumatic events (e.g., Schuster et al., 2001).

Anxiety disorders: It is difficult to differentiate between normal and pathological anxiety and worry about environmental threats, such as climate change. Ecological worrying is a normal and expectable behavior that has been correlated with pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors and with positive personality traits, such as openness and agreeableness (Verplanken & Roy, 2013). This normal worry is often portrayed as “eco-anxiety” in popular media. An anxiety disorder may be diagnosed in the case of obsessive and disabling worry about climate change risks or with evidence of extreme physiological arousal or panic symptoms. It is important to note that psychological stress responses, including those regarding environmental issues, can manifest in a variety of physical symptoms.

Depressive disorders: Responses to natural disasters can be associated with depressive symptoms, including intense sadness, rumination, insomnia, poor appetite, and weight loss. Those experiencing a major impairment lasting 2 weeks or more may meet criteria for a major depressive episode. In issues of disasters or losses, it is important to delineate normal sadness and bereavement from clinical depression, those these may co-exist in the case of highly vulnerable individuals or in those with more severe symptoms or impairments.

Adjustment disorders: In the case of an identifiable stressor associated with marked emotional or behavioral symptoms and significant impairment relative to the community context and cultural norms, a diagnosis of adjustment disorder may be made. Notably, stressors associated with an adjustment disorder may affect a large group or, in the case of a natural disaster, a community. Adjustment disorders are typically self-limiting, but some may be considered chronic in the case of ongoing or unresolved stressors.

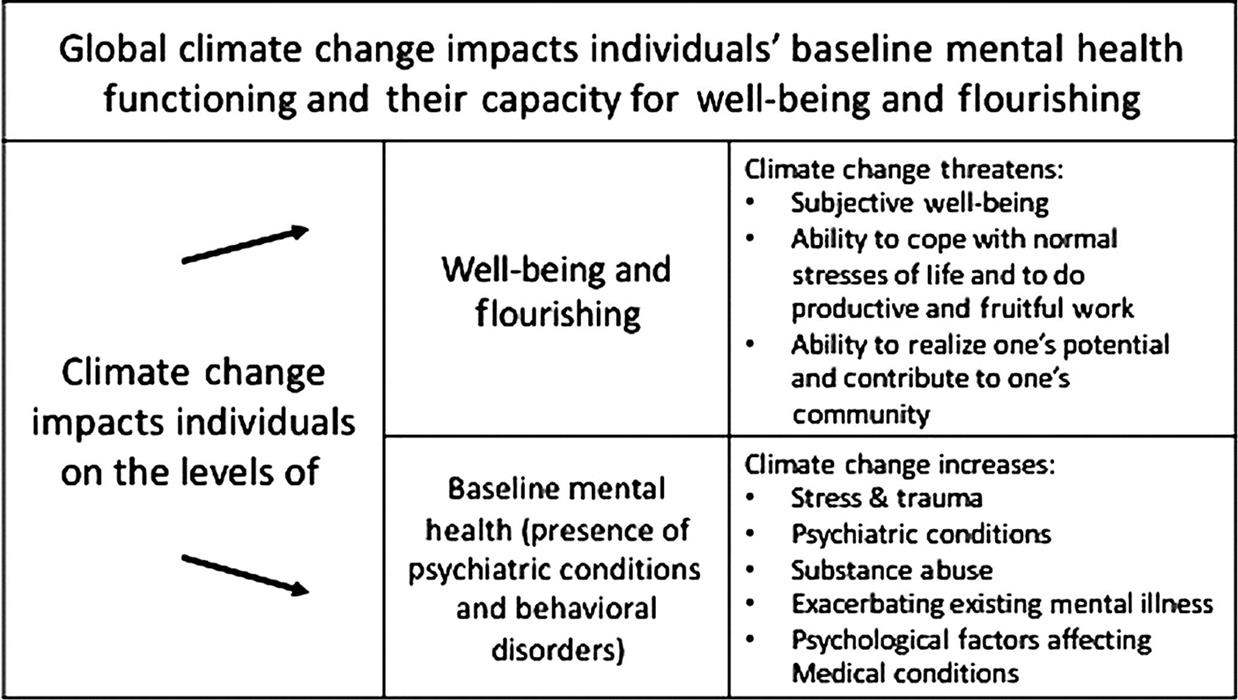

10.5 How climate change threatens psychological flourishing

To fully appreciate the impacts of global climate change on mental health, we must look beyond the prevalence and severity of mental illness and malaise to individuals’ potential for well-being and flourishing. This is particularly important if one uses the perspective of health as a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity (i.e., WHO, n.d.). To assess the full range of climate change’s psychological impacts across all regions and peoples, including among individuals and communities buffered from acute disaster events, it is necessary to view mental illness and mental health and wellness as two distinct continua. Beyond the absence of illness or impairment, mental health and wellness includes the degree to which one feels positive and enthusiastic about their life, can thrive in the face of stress, and can realize their potential to work productively and contribute to her or his community (see Manderscheid et al., 2010).

From a positive psychology perspective (see Keyes, 2007), mental health and wellness includes the potential for flourishing. Climate change inhibits flourishing by impacting peoples’ ability to experience:

It is in the diminishment of mental well-being and flourishing that the more far-ranging and chronic ripple effects of climate change disasters on individual’s mental life become apparent.

Even among globally privileged individuals for whom climate change may be a relatively abstract or distant phenomenon, unfolding climate events and impacts can threaten or delegitimize one’s sense of flourishing, their sense of meaning, and their trust in government and societal potential. This is particularly true when witnessing the frank inequalities among those affected by climate change and the muddled and conflicting societal responses to these issues Fig. 10.2.

10.6 Barriers to psychological coping with climate change: Complexity, disinformation, and powerlessness

In the popular mind, climate change presents a challenging psychological task: Rapid adjustment to changed ecosystems worldwide and an acceptance of human causation and responsibility for environmental losses and extinctions (Kolbert, 2014). Climate change also creates an over-arching narrative that connects and frames disparate global events (e.g., storms and weather events, natural and technological disasters, political and economic issues) with the potential to trouble people’s daily lives and diminish their expectations for the future (Reser & Swim, 2011). Indeed, some theorists contend that perceived public apathy about climate change is more accurately considered paralysis at the size of the problem (see Weintrobe, 2013).

Even in optimum circumstances, the multiple scales inherent in climate change and the conflicted meanings attributed to climate phenomena makes the issue complex and confusing. In real-word settings, individuals must chart a course through the emotions and values of their families and social groups, and the often-abstract scientific nature of climate change discourse (Rudiak-Gould, 2013). Open dialog about climate issues is suppressed due to political polarization, censorship of climate change findings, and active antiscience disinformation and propaganda campaigns (Dunlap, McCright & Yarosh, 2016; Oreskes and Conway, 2010)—and pluralistic ignorance of shared climate concern of one’s fellow citizens (see Chapter 4: Social construction of scientifically grounded climate change discussions). Problems with emotional expression are further enabled by coping styles that can promote various forms of minimization or denial at the individual and social group level (McDonald, Chai & Newell, 2015; Shepherd & Kay, 2012).

Coping with climate change is a global burden that eventually falls on individuals, and is most acutely felt by those who become sensitized to the issue due to their education, values, or direct experiences and vulnerability. There is support for legislation to confront climate action in every county of the United States (Marlon, Fine & Leiserowitz, 2017). However, a fairly small group of powerful corporate actors and elected officials have stymied concerted action (see Dunlap et al., 2016; Oreskes and Conway, 2010). Citizens confronted with urgent calls for action to prevent climactic tipping points are, in effect, “climate hostages” trapped by global political and economic dynamics beyond their control. This is particularly true of groups with limited political or economic power who must cope with local climate impacts created by distant processes (see discussion in Clayton et al., 2017).

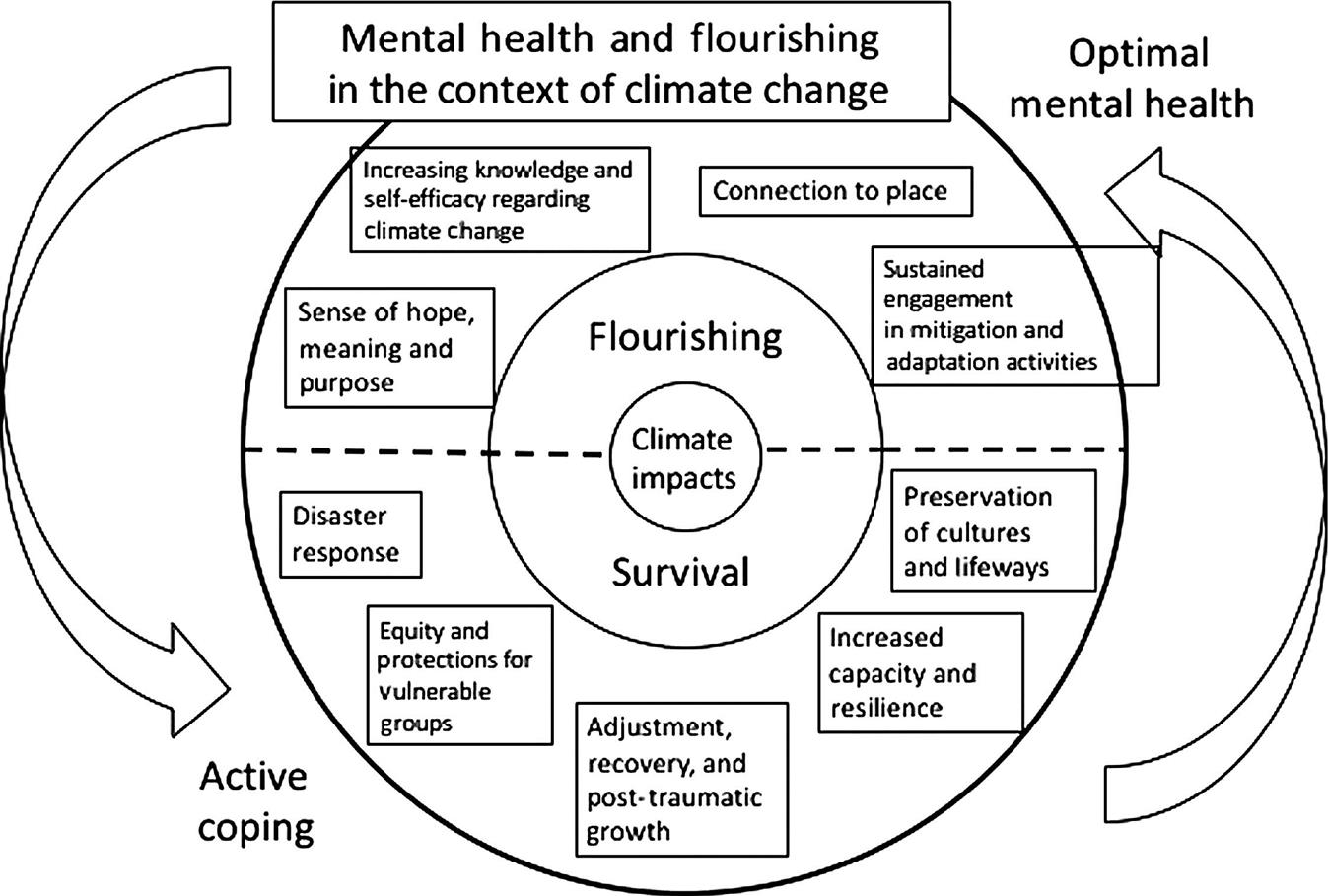

10.7 Steps toward coping with global climate change as an individual

Moving beyond an understanding of mental health impacts of climate change to identify effective long-term strategies and techniques for psychological coping and flourishing is important task for the future research and practice. Across societies, successful coping can come in many forms, including preventive public health measures that promote resiliency and adaptation to environmental changes, therapeutic interventions in response to climate impacts, healing and posttraumatic growth following climate-related trauma. Psychological flourishing in the context of climate change transcends mental health to include positive emotions, self-acceptance, a sense of meaning, and a belief in society. As an initial direction, a systems perspective is one framework that allows for understanding (1) the ways that global scale climate issues affect individual people at local levels and (2) how to rationalize the benefits of individual actions on climate issues at larger scales. Ultimately, adjusting to climate change with integrity and resilience will require a combination of realistic personal goal setting, building one’s capacity for engagement though hopeful imagery and self-restoration, and commitment to long-term actions and goals (including continuing education about climate change, making responsible lifestyle choices, and promoting structural changes in society by engaging in the politic process and undertaking nonviolent activism). As discussed below, resources from disaster mental health, and psychotherapy and counseling can augment individuals’ self-help activities.

Using a systems perspective to give meaning to personal actions: When coping with climate change, it is very important to hold a systems perspective in mind. That is, the phenomenon / problem of climate change is an (1) interconnected set of (2) varied elements (i.e., human and natural systems) that (3) serve varied functions and purposes (i.e., the earth’s climate and weather systems have synergistic interactions with human societies and technological infrastructure) (see Meadows, 2008 for a systems primer). A systems perspective allows us to see how changes in the natural environment (e.g., long-term droughts) can have ripple effects in human systems that in turn affect individual’s personal health and well-being. Systems thinking also opens the possibility that many actions, even small ones, can positively contribute to the situation. For example, if an individual or group can help to ameliorate poverty, improve community healthcare or disaster response capabilities, promote regional cooperation, or create innovative ways to scale up sustainable energy sources, they will be making an important contribution to “solving” the problem of climate change. Further, systems concepts like resilience—the ability of a system to maintain its functions after experiencing a disturbance—guide collective actions that aid in human adaptation to climate change. For example, resilience thinking provides a rationale to protect the biological integrity of sensitive natural areas that in turn buffer communities from weather disasters and promote their long-term functioning (see National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (n.d.); Pelling, 2011; Tompkins & Adger, 2004). Concepts like resilience also provide inspiring images and metaphors that can aid in psychological coping (see Doppelt, 2016).

Finding validation and hope. At the outset, it is important to recognize that just as the mental health impacts of climate change are varied and diverse, so are potential ways to cope and to seek optimum health. In terms of long-term coping outside of disaster situations, there are several potential steps individuals can take. These include adopting positive attitudes and habits and mind, as well as making structural and behavioral changes to one’s life †hat promote a sense of wellness and sustainability. At the level of thought and emotions, honest and reality-based psychological coping requires a balance of acceptance and validation of the troubling and despair-inducing nature of climate issues, including lack of control and sense of being a hostage to larger forces, with an equivalent commitment to hope, creativity, and personal renewal. In the context of long-term climate advocacy, hope can be considered one’s highest vision of the possible, or the ecological world toward which the person strives for through their actions (see Roy & Roy, 2011). Hope constitutes a deep-seated guiding focus that is contrasted with the fluctuating emotions of optimism or pessimism prompted by short-term political and environment events. To support hope and a guiding vision, it is also important to continue to develop, reconnect with, and celebrate one’s environmental values, the core values that prompt concerns with climate change and its negative effects.

Supporting environmental identity and restoration in nature: To the extent, one can articulate their sense of environmental identify (i.e., their personal identity and life history in relation to nature) their potential for integrity regarding their climate-related values and actions is increased. Engagement with climate change can be a way of practicing one’s core values, using one’s personal or professional gifts, expressing meaning and spirituality, and giving back in an altruistic way for the benefits one has received from nature. Climate arts and literature can be an inspiration in this regard. There are increasing number of climate change-related initiatives in the arts, including climate fiction and graphic novels (Milkoreit, Martinez & Eschrich, 2016; Squarzoni, 2014) as well as theater, photography and visual arts (e.g., see Bilodeau, 2016; Cape Farewell Project, n. d.). These works illustrate the individual journeys of the creators and provide examples of how people engage with the complex emotions and ethical dilemmas they experience regarding climate change. Memories of past growth-enhancing and restorative experiences in the outdoors and with other species provide examples for nature-based activities that individuals can practice for restoring their health, well-being and positive emotions. As the author has counseled individuals suffering from environmental grief: “Despair is fatigue in disguise.” Restoration in nature through active adventures and recreation, or through esthetic or relaxing activities can re-inspire motivation and creativity.

Linking climate adaptation and mitigation with mental health: It is helpful for mental health professionals seeking to address climate change impacts to be familiar with the scientific literature on climate change, in particular, concepts of climate change mitigation and adaptation (see Chapter 1: Introduction: Psychology and climate change). Most therapeutic activities associated with climate change can be considered efforts to adapt to changes and mental health impacts. Further, the idea of going a step farther and seeking to prevent mental health impacts by addressing their causes move into the realm of climate change mitigation. In practice, efforts toward mental health, adaptation, and mitigation are entwined. For examples, for individuals who are experiencing climate impacts—and who also have resources and empowerment—strong feelings, personal responsibility and an impulse to take corrective action are an expected psychological response (see Reser & Swim, 2011). These feelings and motivations can in turn mediate those individuals’ engagement in environmentally significant behaviors, such as seeking to limit their greenhouse gas emissions (Milfont, 2012). Promoting people’s confidence in their ability to adapt to climate impacts can also increase their confidence to act to address the primary drivers of climate change—a so-called “adaptation-mitigation cascade” (see Doherty, 2015a, p. 208). In this regard, it is very important to promote the coping of privileged people who are minimally affected by climate change directly but are experiencing vicarious stressors and traumas. Their adaptation to vicarious impacts can encompass mitigation behaviors on their part, for example, when people in industrialized nations address their climate concerns by adopting a lifestyle with a smaller carbon footprint.

A focus on the co-benefits of climate action is also important to note. Echoing systems insights, a “personal sustainability” perspective (Doherty, 2015b) reminds us that humans are an integral part of nature. Actions that improve a person’s individual health such as pursuing rest, exercise, nurturing social interactions, and engaging in restorative nature activities can be seen as ecological acts. This is not simply a matter of philosophy. As Clayton et al., (2017) note, behavioral options to address climate change are available now, are widespread, and these also tend to support individuals’ psychological health. For example, increased adoption of active commuting, public transportation, green spaces, and clean energy are solutions that people can support and integrate into their daily lives, and help to curb stress, anxiety, and other mental problems incurred from the decline of economies, infrastructure, and social identity that comes from damage to the global climate.

Directly addressing climate justice issues: For marginalized individuals facing impacts and suffering from limited survival options, coping with climate change will begin with petitioning for social and environmental justice and “speaking truth to power.” When addressing climate impacts with individuals in marginalized communities, there are several strategies useful to foster individuals’ empowerment. These are drawn from an intersectionality framework (Rosenthal, 2016). It is important to recognize and collaborate with community members as social actors with agency, who are responding to and not simply experiencing global climate change and its impacts. It is appropriate to call out and critique unjust social structures and to build coalitions of individuals experiencing similar stressors. In the context of unjust or oppressive systems, it is necessary to recognize the value to individuals of resistance as well as resilience. To promote engagement, it is often necessary to begin with consciousness raising about climate issues and to support education and fact finding on the part of community members so they can tell their story. Local public health departments and grassroots environmental justice organizations are important resources for individuals seeking to become involved. Initial consciousness raising can in turn prompt education, increased awareness of issues and strategies, and more potential for people to see themselves as empowered agents of change. From a legal perspective, those seeking redress for environmental justice cases often use a pragmatic “whatever works” approach that includes knowledge of governance, legal statutes and scientific information, and also community organizing, media messaging, lobbying efforts, negotiations, and other tactics (Zachek, Rubin & Scammell, 2015) Fig. 10.3.

The potential for optimal mental health and flourishing (e.g., hope, efficacy, connection to place, and engagement in mitigation activities) is built on a foundation of coping responses and outcomes predicated by individuals’ survival needs (e.g., disaster response, adjustment and recovery, resilience, and cultural preservation).

10.8 Therapeutic responses to climate change impacts

Beyond self-help coping attempts, there is a spectrum of therapeutic practices with the potential to help individuals experiencing mental health impacts of climate change. These range from public health measures, to disaster response, and to counseling and psychotherapy. Ensuring mental health in a climate change context includes both alleviating symptoms and problems as well as promoting strengths and supporting personal expression and empowerment. Indeed, an important and under-recognized task of mental health professionals is helping individuals imagine a life of flourishing and meaning while maintaining a full consciousness of climate change and its complexity. Improving mental health at the individual level also includes empowering individuals to identify their resources for engaging with the climate issues that affect them. For example, mental health professionals can help people to identify information needed to educate themselves about how climate change affects their region or community, and to envision what climate-related actions they might take in their own lives, given their other life priorities, their social milieu, and the resources or skills they can offer.

Disaster mental health interventions: In the aftermath of disasters, early interventions to assist with basic needs and functional recovery have profound benefits; the most effective measures at the personal level are attentive to family context and emotional factors (Norris, Friedman & Watson, 2002). Effective disaster response can create the conditions for recovery and resiliency among affected individuals. For example, evidence and experience show that people who feel safe, connected, calm, and hopeful; have access to social, physical, and emotional support; and find ways to help themselves after a disaster will be better able to recover long-term from mental health effects (see http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs383/en/). Thus, early to mid-stage intervention and prevention measures should promote a sense of safety, self-efficacy, connectedness, and hope (e.g., by helping individuals to reconnect with family and friends and begin to imagine their recovery plans, see Hobfoll, Watson & Carl, 2007). Post-disaster efforts can also support people’s sense of place and connections to their home region, through recognizing and honoring people’s personal environmental identity and local cultural traditions and values. (Re)connection to place may entail either rebuilding a home or finding a new home in the case of relocation or refugee status.

Mental health providers serving disaster victims should remain aware of the potential for resilience and posttraumatic growth. After disasters, resilient individuals will continue to have positive emotions and show only minor and transient disruptions in their ability to function. This resiliency is a trajectory distinct from an injury-recovery process (Bonanno, 2004). Further, as examples of posttraumatic growth, some individuals come through a significant disruption with the feeling of having gained something positive, such as stronger social relationships, specific skills, or insights about their lives and home regions (Lowe, Manove & Rhodes, 2013; Ramsay & Manderson, 2011). Therapeutic activities can deepen individual’s sense of healing and posttraumatic growth following disasters and, in turn, build future resilience.

Addressing climate change in psychotherapy and counseling: Short-term cognitive behavioral therapies can be useful to help those recovering from disasters to transition from high stress and life disruptions, to set goals, and to assess barriers to rebuilding their lives. For individuals experiencing indirect or vicarious impacts, cognitive behavioral therapies can help individuals to assess environmental threats, to base these on realistic appraisals of their life situations, and to commit to concrete actions that address their concerns and are within their scope of influence. Existential-humanistic or mindfulness-based therapies can help individuals to build their capacity to be present with the gravity and complexity of climate change while also creating a holding space for their emotional responses. Nature-based counseling and ecotherapy may be a particularly good fit for individuals with strong environmental values and connection with place (see Doherty, 2016). Any approach that encourages people to spend time doing safe, nature-based, activities, such as outdoor walking, gardening, or recreational activities can be helpful to reduce physiological stress, take a break from social or news media, and promote perspective-taking and creativity. For many individuals, nature is also a space to reconnect with their deeper spiritual or religious values.

Climate-specific psychotherapies: In addition to standard psychotherapeutic approaches, mental health theorists and clinicians have begun to create more specific guidance regarding climate change and other environmental issues. Writings in the ecopsychology tradition have long considered the interplay between personal mental health, connection to nature and the experience of environmental losses (e.g., Nicholsen, 2001; Macy & Young-Brown, 1998; Roszak, Gomes & Kanner, 1995). Weintrobe (2013) and Kiehl (2016) have approached climate change from the perspective of psychoanalytic and Jungian psychotherapy, while Davenport (2017) has created a clinician’s guide to resiliency in an era of climate change. Randall (2009) has developed a group therapy for individuals coping with climate change and other environmental concerns. More recently, grassroots initiatives based on a 12-step Recovery approach have addressed people’s grief about climate change (see Simmons, 2016). What these approaches have in common is a validation of the emotional aspects of climate change and engagement of the affected individuals’ values and hopes. By creating connections among like-minded individuals and a space to share stories and receive social support, these interventions create an opportunity for distressed individuals to move from isolation and despair to a sense of community and empowerment. To the extent that individuals can create or recover a sense of ecological connectedness to their home places, and see their local climate actions as important, they are less likely to fall prey to a disempowering focus on distant global problems beyond their control.

10.9 A positive message: Thriving in the era of global climate change

When reflecting on the mental health impacts of global climate change, one is confronted by two truths: We are all living as a “Climate Hostages” on a warming planet, and all humans have the potential for flourishing in adverse conditions. From a positive perspective, climate change is an invitation to reframe global consciousness from that of a collection of over-arching “wicked problems” to a wealth of possibilities for humanitarian and ecological actions. No one person or group can possibly address all the systemic issues related to global climate change. This realization is sobering. But, it also contains seeds of possibility for coping and response. The systemic nature of global climate change allows for many ways to engage. To positively address the problem of climate change, each person or group must engage with and help solve the problems within their scope of influence. Making progress on any one set of issues can contribute to both local and widespread solutions. As noted, if an individual or group can help to ameliorate poverty, improve regional cooperation, create innovative ways to scale up sustainable energy sources, or improve community healthcare or disaster response capabilities, they will be making an important contribution to “solving” the problem of climate change.

This chapter addressed the challenge of framing the mental health impacts of climate change broadly, by examining a spectrum of issues from direct and acute disaster impacts, to chronic social and economic stresses, to despair at witnessing climate problems at a distance. The mental health functioning of individuals was distinguished from their positive opportunities for flourishing, as these are both negatively affected by climate change. Groups vulnerable to climate change impacts and common barriers to coping were highlighted, as well as strategies for engagement and personal and therapeutic responses. To foster psychological flourishing in the context of climate change requires protecting and bolstering mental health in the wake of disasters as well as promoting positive emotions, a sense of meaning, and belief in society. To this end, psychologists and other mental health professionals have a role to play as researchers, disaster first responders, and as confidants in intimate therapeutic settings. To the extent that individuals (and psychologists and other mental health professionals) can manifest their potential for flourishing, and to use their capabilities to address the societal impacts of climate change within their scope of influence, it is possible to imagine thriving in an era of global climate change.