6

Interviewing

The aim of an interview is to provide, in the interviewee's own words, facts, reasons or opinions on a particular topic so that the listener can form a conclusion as to the validity of what he or she is saying.

The basic approach

It follows from the above definition that the opinions of the interviewer are irrelevant. An interview is not a confrontation, which it is the interviewer's object to win. A questioner whose attitude is one of battle, to whom the interviewee represents an opponent to be defeated, will almost inevitably alienate the audience. The listener quickly senses such hostility and, feeling that the balance of advantage already lies with the broadcaster, the probability is of siding with the underdog. For an interviewer to be unduly aggressive, therefore, is counter-productive. On the other hand, an interview is not a platform for the totally free expression of opinion. The assertions made are open to be challenged.

The interviewer should never get drawn into answering a question that the interviewee may put – an interview is not a discussion. We are not concerned here with what has been referred to as ‘the personality interview’ where the interviewer, often the host of a television ‘chat show’, acts as the grand inquisitor and asks guests their opinions on a whole range of topics. Within this present definition it is solely the interviewee who must come through and in the interviewer's vocabulary the word ‘I’ should be absent. Deference is not required but courtesy is; persistence is desirable, harassment not. The interviewer is not there to argue, to agree or disagree, nor to comment on the answers. The interviewer's job is simply to ask appropriate and searching questions, and this requires good preparation and astute listening.

The interview is essentially a spontaneous event. Any hint of its being rehearsed damages the interviewee's credibility to the extent of the listener believing the whole thing to be ‘fixed’. For this reason, while the topic may be discussed generally beforehand, the actual questions should not be provided in advance. The interview must be what it appears to be – questions and answers for the benefit of the eavesdropping listener. The interviewer is acting on behalf of the listener, asking the questions which the listener would want to ask. More than this, it is an opportunity to provide not only what the listener wants to know, but also what the public may need to know. At least as far as the interviewing of political figures is concerned, the interview should represent a contribution towards a democratic society, i.e. the proper questioning of people who, because of the office they hold, are accountable to the electorate. It is a valuable element of broadcasting and care should be taken to ensure it is not damaged, least of all by casual abuse in the cult of personality on the part of broadcasters.

Types of interview

For the sake of simplicity three types of interview can be identified, although any one situation may involve all three categories to a greater or lesser extent. These are the informational, the interpretive and the emotional interviews.

Obviously, the purpose of the informational interview is to impart information to the listener. The sequence in which this is done becomes important if the details are to be clear. There may be considerable discussion beforehand to clarify what information is required and to allow time for the interviewee to recall or check any statistics. Topics for this kind of interview include: the action surrounding a military operation, the events and decisions made at a union meeting, or the proposals contained in the city's newly announced development plan.

The interpretive interview has the interviewer supplying the facts and asking the interviewee either to comment on them or to explain them. The aim is to expose the reasoning behind decisions and allow the listener to make a judgement on the implicit sense of values or priorities. Replies to questions will almost certainly contain statements in justification of a particular course of action which should themselves also be questioned. The interviewer must be well briefed, alert and attentive to pick up and challenge the opinions expressed. Examples in this category would be a government minister on the reasons for an already published economic policy, why the local council has decided on a particular route for a new road, or views of the clergy on proposals to amend the divorce laws. The essential point is that the interviewer is not asking for the facts of the matter, since these will be generally known; rather he or she is investigating the interviewee's reaction to the facts. The discussion beforehand may be quite brief, the interviewer outlining the purpose of the interview and the limits of the subject to be pursued. Since the content is reactive, it should on no account be rehearsed in its detail.

The aim of the emotional interview is to provide an insight into the interviewee's state of mind so that the listener may better understand what is involved in human terms. Specific examples would be the feelings of relatives of people trapped in the debris of an earthquake, the euphoria surrounding the moment of supreme achievement for an athlete or successful entertainer, or the anger felt by people involved in an industrial dispute. It is the strength of feeling present rather than its rationality which is important and clearly the interviewer needs to be very sensitive in handling such situations. There is praise and acclaim for asking the right question at the right time in order to illuminate a matter of public interest, even when the event itself is tragic. But quick criticism follows for being too intrusive into private grief. It is in this respect that the manner of asking a question is as important as its content, possibly more so.

Another difficulty that faces the interviewer here is to reconcile the need to remain an impartial observer while not appearing indifferent to the suffering in the situation. The amount of time taken in preliminary conversation will vary considerably depending on the circumstances. Establishing the necessary relationship may be a lengthy process – but there is a right moment to begin recording and it is important for the interviewer to remain sensitive to this judgement. Such a situation allows little opportunity for retakes.

These different categories of interview are likely to come together in preparing material for a documentary or feature. First, the facts, background information or sequence of events; then, the interpretation, meaning or implication of the facts; finally, their effect on people, a personal reaction to the issue. The documentary interview with, for example, a retired politician will take time but should be as absorbing for the interviewer as it will be for the listener. The process of recalling history should surprise, it should throw new light on events and people, and reveal the character of the person. Each interview is different but two principles remain for the interviewer – listen hard and keep asking ‘why?’

Related to the documentary interview, but not concerned necessarily with a single topic, is the style of interviewing that contributes to oral history. Every station, national, regional or local, should assume some responsibility for maintaining an archival record of its area. Not only does it make fascinating material for future programmes, but it becomes of value in its own right as it marks the changes which affect every community. The old talking about their childhood or their parents’ values, craftsmen describing their work, children on their expectations of growing up, the unemployed, music makers, shopkeepers, old soldiers. The list is endless. The result is an enriching library of accent, story, humour, nostalgia and idiosyncrasy. But to capture the voices of people unused to the microphone takes patience and a genuinely perceptive interest in others. It may take time to establish the necessary rapport and to put people at their ease. On the other hand, when talking to the elderly, it is often advisable to start recording as soon as the interviewee recounts any kind of personal memory. They may not understand whether or not the interview has begun and will not be able to repeat what they said with the same freshness. Preparation and research beforehand into personal backgrounds help to recall facts and incidents that the interviewee often regards as too insignificant or commonplace to mention. People generally like talking about themselves and it takes a quick-thinking flexibility to respond appropriately, to know when a conversation should be curtailed and when moved on. The rewards, however, are considerable. A final point: such recordings need to be well documented – it is one thing to have them in the archives, but quite another to secure their speedy and accurate retrieval.

Securing the interviewee

An initial telephone call may secure consent to an interview, enabling the interviewer to arrive with a portable recorder later that day. Alternatively, arrange a studio interview several days in advance, giving time for the interviewee to prepare. It has been known, of course, for interviewers to arrive equipped with a recorder and ask for an interview on the spot – or even telephone and tell the interviewee that he or she is already on the air! This last technique is bad practice, and besides contravenes the basic right of an interviewee that no telephone conversation will be broadcast or recorded without consent. There can be no question of doing this without their knowledge (see Secret recording, p. 270). It should be a standard procedure for all broadcasters that in telephoning a potential interviewee nothing is begun, recorded or transmitted without the interviewee being properly informed about the station's intention. Even so, to be rung up and asked for an interview there and then is asking a great deal. It is in no one's interest, least of all the listener's, to have an ill-thought-out interview with incomplete replies and factual errors.

What the interviewee should know

Since it is impossible to interview someone who does not want to be interviewed, it is reasonable to assume that the arrangement is mutually agreed. The broadcaster, in contacting a potential interviewee, asks whether an interview might take place. The information that the interviewee needs at this point is:

1 What is it to be about? Not the exact questions but the general areas, and the limits of the subject.

2 Is it to be broadcast live or recorded?

3 How long is it to be? Is the broadcast a major programme or a short item? This sets the level at which the subject can be dealt with and helps to guard against the interviewee recording a long interview without being aware that it must be edited to another length.

4 What is the context? Is the interview part of a wider treatment of the subject with contributions from others or a single item in a news or magazine programme?

5 For what audience? A local station, network use, for syndication?

6 Where? At the studio or elsewhere?

7 When? How long is there for preparation?

No potential interviewee should feel rushed into undertaking an interview and certainly not without establishing the basic information outlined above. Sometimes a fee is paid, but this is unlikely in community radio; it is worth making this clear.

Preparation before the interview

It is essential for the interviewer to know what he or she is trying to achieve. Is the interview to establish facts or to discuss reasons? What are the main points that must be covered? Are there established arguments and counter-arguments to the case? Is there a story to be told? The interviewer must obviously know something of the subject and a briefing from the producer, combined with some personal research, is highly desirable. An essential is absolute certainty of any names, dates, figures or other facts used within the questions. It is embarrassing for the expert interviewee to correct even a trifling factual error in a question – it also represents a loss of control. For example:

‘Why was it only three years ago that you began to introduce this new system?’

‘Well actually it was five years ago now.’

It is important, although easily capable of being overlooked, to know exactly who you are talking to:

‘As the chairman of the company, how do you view the future?’

‘No, I'm the managing director …’

It makes no difference whatsoever to the validity of the question but a lack of basic care undermines the questioner's credibility in the eyes of the interviewee and, even more important, in the ears of the listener.

Having decided what has to be discovered, the interviewer must then structure the questions accordingly. Question technique is dealt with in a later section, but it should be remembered that what is actually asked is not necessarily formulated in precise detail beforehand. Such a procedure could easily be inflexible and the interviewer may then feel obliged to ask the list of questions irrespective of the response by the interviewee. Preparation calls for the careful framing of alternative questions – with consideration of the possible responses so that the next line of enquiry can be worked out.

For example, you want to know why a government minister is advocating the closure of coal mines with a large amount of resulting unemployment. If the question put is simply ‘Why are you advocating … ?’, the reply is likely to be a stock answer on the need for pits to be economic. Such a response is known by most people so the interview merely repeats the position, it does not carry the issue forward. To move ahead, the interviewer must anticipate and be in a position to put questions that well-informed people in the industry are asking – about other markets for coal, the relative operating and capital costs of coal-fired and gas power and nuclear stations, the cost to the country of unemployed mineworkers, possible relief measures, and so on.

To summarize, an interviewer's normal starting point will be:

1 To obtain sufficient briefing and background information on the subject and the interviewee.

2 To have a detailed knowledge of what the interview should achieve, and at what length.

3 To know what the key questions are.

4 By anticipating likely responses, to have ready a range of supplementary questions.

The pre-interview discussion

The next stage, after the preparatory work, is to discuss the interview with the interviewee. The first few minutes are crucial. Each party is sizing up the other and the interviewer must decide how to proceed.

There is no standard approach: each occasion demands its own. The interviewee may respond to the broadcaster's brisk professionalism or might better appreciate a more sympathetic attitude. He or she may need to feel important, or the opposite. The interviewee in a totally unfamiliar situation may be so nervous as to be unable to marshal their thoughts properly; their entire language structure and the speed of delivery may be affected. Under stress it may not even be possible to listen fully to your questions. The good interviewer will be aware of this and will work hard to enable the interviewee's thinking and personality to emerge. Whatever the circumstances, the interviewer has to get it right, and has only a little time in which to form the correct judgements.

The interviewer indicates the subject areas to be covered but is well advised to let the interviewee do most of the talking. This is an opportunity to confirm some of the facts, and it helps the interviewee to release some of the tensions while allowing the interviewer to anticipate any problems of language, coherence or volume.

It is wrong for the interviewer to get drawn into a discussion of the matter, particularly if there is a danger of revealing a personal attitude to the subject. Nor is it generally helpful to adopt a hostile manner or imply criticism. This may be appropriate during the interview, but even so it is not the interviewer's job to conduct a judicial enquiry or to act as prosecuting counsel, judge and jury.

The interviewer's prime task at this stage is to clarify what the interview is about and to create the degree of rapport that will produce the appropriate information in a logical sequence at the right length. It is a process of obtaining the confidence of the interviewee while establishing a means of control. A complex subject needs to be simplified and distilled for the purposes of, say, a three-minute interview – there must be no technical or specialist jargon, and the intellectual and emotional level must be right for the programme. Above all, the end result should be interesting.

It is common and useful practice to say beforehand what the first question will be, since in a ‘live’ situation it can help to prevent a total ‘freeze’ as the red light goes on. If the interview is to be recorded, such a question may serve as a ‘dummy’ to be edited out later. In any event, it helps the interviewee to relax and to feel confident about starting. The interviewer should begin the actual interview with as little technical fuss as possible, the preliminary conversation proceeding into the interview with the minimum of discontinuity.

Question technique

An interview is a conversation with an aim. On the one hand, the interviewer knows what that aim is and knows something of the subject. On the other, by taking the place of the listener he or she is asking questions in an attempt to discover more. This balance of knowledge and ignorance can be described as ‘informed naivety’.

The question type will provide answers of a corresponding type. In their simplest form they are:

| 1 Who? | asks for fact. Answer – a person. |

| 2 When? | asks for fact. Answer – a time. |

| 3 Where? | asks for fact. Answer – a place. |

| 4 What? | asks for fact or an interpretation of fact. Answer – a sequence of events. |

| 5 How? | asks for fact or an interpretation of fact. Answer – a sequence of events. |

| 6 Which? | asks for a choice from a range of options. |

| 7 Why? | asks for opinion or reason for a course of action. |

These are the basic ‘open’ question types on which there are many variations. For example:

‘How do you feel about … ?’

‘To what extent do you think that … ?’

The best of all questions, and incidentally the one asked least, is ‘why?’ Indeed, after an answer it may be unnecessary to ask anything other than ‘why is that?’ The ‘why’ question is the most revealing of the interviewee, since it leads to an explanation of actions, judgements, motivation and values:

‘Why did you decide to … ?’

‘Why do you believe it necessary to … ?’

It is sometimes said that it is wrong to ask ‘closed’ questions based on the ‘reversed verb’:

Are you … ?

Is it …?

Will they … ?

Do you … ?

What the interviewer is asking here is for either a confirmation or a denial; the answer to such a question is either yes or no. If this is really what the interviewer is after, then the question structure is a proper one. If, however, it is an attempt to introduce a new topic in the hope that the interviewee will continue to say something other than yes or no, it is an ill-defined question. As such, it is likely to lead to the interviewer's loss of control, since it leaves the initiative completely with the interviewee. In this respect, the reversed verb question is a poor substitute for a question that is specifically designed to point the interview in the desired direction. The reversed verb form should therefore only be used when a yes/no answer is what is required:

‘Will there be a tax increase this year?’

‘Are you running for office in the next election?’

Question ‘width’

This introduces the concept of how much room for manoeuvre the interviewer is to give the interviewee. Clearly, where a yes/no response is being sought, the interviewee is being tied down and there is little room for manoeuvre; the question is very narrow. On the other hand, it is possible to ask a question that is so enormously wide that the interviewee is confused as to what is being asked:

‘You've just returned from a study tour of Europe, tell me about it.’

This is not of course a question at all, it is an order. Statements of this kind are made by inexperienced interviewers who think they are being helpful to a nervous interviewee. In fact, the reverse is more likely, with the interviewee baffled as to where to start.

Another type of question, which again on the face of it seems helpful, is the ‘either/or’ question:

‘Did you introduce this type of engine because there is a new market for it, or because you were working on it anyway?’

The trouble here is that the question ‘width’ is so narrow that, in all probability, the answer lies outside it, so leaving the interviewee little option but to say ‘Well neither, it was partly …’. Things are seldom so clear-cut as to fall exactly into one of two divisions. In any case, it is not up to the interviewer to suggest answers. What the questioner wanted to know was:

‘Why did you introduce this type of engine?’

A currently common but slightly vague question form is: ‘What do you make of … ?’ This is generally preceded by a synopsis of a situation, event or comment which ends with: ‘What do you make of the report/what she said/the minister's decision?’, etc. Akin to ‘What do you think of … ?’ It's a very wide question, leaving a lot of latitude for the response.

Devil's advocate

If an interviewee is to express his or her own point of view fully and to answer various critics, it will be necessary for those opposing views to be put. This provides the opportunity of confronting and demolishing the arguments to the satisfaction, or otherwise, of the listener. In putting such views, the interviewer must be careful not to become associated with them, nor to be associated in the listener's mind with the principle of opposition. The role is to present propositions that are known to have been expressed elsewhere, or to voice the doubts and arguments which can reasonably be expected to exist in the listener's mind. In adopting the ‘devil's advocate’ approach, common forms of question are:

‘On the other hand, it has been said that …’

‘Some people would argue that …’

‘How do you react to people who say that …’

‘What would you say to the argument that …’

The first two examples as they stand are not questions but statements, and if left as such will bring the interview dangerously close to being a discussion. The interviewer must ensure that the point is put as an objective question.

It has been said in this context that ‘you can't play good tennis with a bad opponent’. The way in which broadcasters present counter-arguments needs care, but experienced interviewees welcome it as a means of making their case more easily understood.

Multiple questions

A trap for the inexperienced interviewer, obsessed with the fear that the interviewee will be lacking in response, is to ask two or more questions at once:

‘Why was it that the meeting broke up in disorder, and how will you prevent this happening in future? Was there a disruptive element?’

The interviewee presented with two questions may answer the first and then genuinely forget the second, or may exercise the apparent option to answer whichever one is easier. In either case there is a loss of control on the part of the interviewer, as the initiative passes to the interviewee.

Questions should be kept short and simple. Long rambling circumlocutory questions will get answers in a similar vein; this is the way conversation works. The response tends to reflect the stimulus – this underlines the fact that the interviewer's initial approach will set the tone for the whole interview.

Beware the interviewer who has to clarify the question after asking it:

‘How was it you embarked on such a course of events, I mean what made you decide to do this – after all, at the time it wasn't the most obvious thing to do, was it?’

Confusion upon confusion, and yet this kind of muddle can be heard on the air. If the purpose of the question is not clear in the interviewer's mind, it is unlikely to be understood by the interviewee – the listener's confusion is liable to degenerate into indifference and subsequent total disinterest.

Leading questions

Lazy, inexperienced or malicious questioning can appear to cast the interviewee in an unfavourable light at the start:

‘Why did you start your business with such shaky finances?’

‘How do you justify such a high-handed action?’

It is not up to the interviewer to suggest that finances are shaky or that action is high-handed, unless this is a direct quote of what the interviewee has just said. Given the facts, the listener must be able to determine from what the interviewee says whether the finances were sufficient or whether the action was unnecessarily autocratic. Adjectives which imply value judgements must be a warning signal, for interviewee and listener alike, that all is not quite what it appears to be. Here is an interviewer who has a point to make, and in this respect may not be properly representing the listener. The questions can still be put in a perfectly acceptable form:

‘How much did you start your business with?’ (fact)

‘At the time, did you regard this as enough?’ (yes/no)

‘How do you view this now?’ (judgement)

‘What would you say to people who might regard this action as highhanded?’ (the ‘devil's advocate’ approach already referred to)

It is surprising how one is able to ask very direct, personally revealing, ‘hard’ questions in a perfectly acceptable way by maintaining at the same time a calmly pleasant composure. When a broadcaster is criticized for being over-aggressive, it is generally the manner rather than the content that is being questioned. Even persistence can be politely done:

‘With respect, the question was why this had happened’

In asking why something happened it is not uncommon to get in effect how it happened, particularly if the interviewee wishes to be evasive. Evasion a second or third time becomes obvious to the listener and there is no need for the interviewer to labour the point: it is already made.

Non-questions

Some interviewers delight in making statements instead of asking questions. The danger is that the interview may become a discussion. For example, an answer might be followed by the statement ‘This wouldn't happen normally’ instead of with the question ‘Is this normal?’ Again, the statement ‘You don't appear to have taken that into account’ instead of the question ‘To what extent have you taken that into account?’

The fault lies in the question not being put in a positive way so that the interviewee can respond as he or she likes, perhaps by asking a question. The interviewer may then find it difficult to exercise control over both the subject matter and the timing.

Occasionally, interviewers ask whether they can ask questions:

‘Could I ask you if …’

‘I wonder whether you could say why …’

This is unnecessary, of course, since in the acceptance of the interview there is an agreement to answer questions. There may occasionally be justification for such an approach when dealing with a particularly sensitive area and the interviewer feels the need to proceed gently. This phraseology can be used to indicate that the interviewer recognizes the difficulty inherent in the question. Much more likely, however, it is used by accident when the questioner is uncertain as to the direction of the interview and is ‘padding’ in order to create some thinking time. Such a device is likely to give the listener the feeling that time is actually being wasted.

Non-answers

The accidental evasion of questions may be due to the interviewee genuinely misunderstanding the question, or the question may have been badly put; in either case the interview goes off on the wrong tack. When recording this is easily remedied, but if it happens on the air the listener may be unable to follow and lose interest, or regard the interviewee stupid or the interviewer incompetent. One or other of the parties must bring the subject back to its proper logic.

The deliberately evasive technique often adopted by the non-answerer is to follow the interviewer's question with another:

‘That certainly comes into it, but I think the real question is whether …’

If the new question genuinely progresses the subject, the listener will accept it. If not, the expectation is that the interviewer will put the question again. Rightly or wrongly, the listener will invariably believe that someone who does not answer has something to hide and is therefore suspect.

There may be genuine reasons why ‘No comment’ is an acceptable answer to a question. The facts may not yet be known with sufficient certainty, there may be a legal process pending, a need to honour a guarantee given to a third party, or the answer should properly come from another quarter. It may be that an interviewee legitimately wishes to protect commercially sensitive information – a factor that occurs in the sporting as well as the business world.

Nevertheless, the interviewee must be seen to be honest and to say why an answer cannot be given:

‘It would be wrong of me to anticipate the report …’

‘I can't say yet until the enquiry is finished …’

‘I'm sure you wouldn't expect me to give details, but …’

Even if the inability to give a particular answer has been discussed beforehand, an interviewee should still expect to have the question put if it is likely to be in the listener's mind.

Non-verbal communication

Throughout the interview, the rapport established earlier must continue. This is chiefly done through eye contact and facial expression. Once the interviewer stops looking at the respondent, perhaps for a momentary glance at the equipment or a page of notes, there is a danger of losing the thread of the interview. At worst, the interviewee will look away, and then thoughts as well as eyes are liable to wander. The concentration must be maintained. The eyes of the interviewer will express interest in what is being said – the interviewer is never bored. It is possible to express surprise, puzzlement or encouragement by nodding one's head. In fact, it quickly becomes annoying to the listener to have these reactions in verbal form – ‘ah yes’, ‘mm’, ‘I see’.

Eye contact is also the most frequent means of controlling the timing of the interview – of indicating that another question needs to be put. It may be necessary to make a gesture with the hand, but generally it is acceptable to butt in with a further question. Of course, the interviewer must be courteous and positive to the point of knowing exactly what to say. Even the most talkative interviewee has to breathe and the signs of such small pauses should be noted beforehand so that the interviewer can use them effectively.

During the interview

The interviewer must be actively in control of four separate functions – the technical, the direction of the interview, the supplementary question and the timing.

The technical aspects must be constantly monitored. Is the background noise altering, so requiring a change to the microphone position? Is the position of the interviewee changing relative to the microphone, or have the voice levels altered? If the interview is being recorded, is the machine continuing to function correctly and the meter or other indicator giving a proper reading?

The aims of the interview must always be kept in mind. Is the subject matter being covered in terms of the key questions decided beforehand? Sometimes it is possible for the interviewer to make a positive decision and change course, but in any event it is essential to keep track of where the interview is going.

The supplementary question – it is vital that the interviewer is not so preoccupied with the next question as to fail to listen to what the interviewee is saying. The ability to listen and to think quickly are essential attributes of the interviewer. This leads to the facility of being able to ask the appropriate follow-up question for clarification of a technicality or piece of jargon, or to question further the reason for a particular answer. Where an answer is being given in an unnecessarily academic or abstract way, the interviewer should ask to have it turned into a factual example.

The timing of the interview must be strictly adhered to. This is true whether the interview is to be of half an hour or two minutes. If a short news interview is needed, there is little point in recording 10 minutes with a view to reducing it to length later. There may be occasions when such a time-consuming process will be unavoidable, even desirable, but the preferred method must be to sharpen one's mind beforehand, rather than rely on editing afterwards. Thus, the interviewer when recording keeps a mental clock running. It stops when it hears an answer which is known to be unusable but continues again on hearing an interesting response. This controls the flow of material so that the subject is covered as required in the time available. This sense of time is invaluable when it comes to doing a ‘live’ interview when, of course, timing is paramount. Such a discipline is basic to the broadcaster's skills.

Winding up

The word ‘finally’ should only be used once. It may usefully precede the last question as a signal to the interviewee that time is running out and that anything important left unsaid should now be included. Other signals of this nature are words such as:

‘Briefly, why …’

‘In a word, how …’

‘At its simplest, what …’

It is a great help in getting an interviewee to accept the constraint of timing if the interviewer has remembered to say beforehand the anticipated duration.

Occasionally, an interviewer is tempted to sum up. This should be resisted since it is extremely difficult to do without making some subjective evaluations. It should always be borne in mind that one of the broadcaster's greatest assets is an objective approach to facts and an impartial attitude to opinion. To go further is to forget the listener, or at least to underestimate the listener's own ability to form a conclusion. A properly structured interview should have no need of a summary, much less should it be necessary to impose on the listener a view of what has been said.

If the interview has been in any sense chronological, a final question looking to the future will provide an obvious place to stop. A positive convention as an ending is simply to thank the interviewee for taking part:

‘Mr Jones, thank you very much.’

However, an interviewer quickly develops an ear for a good out-cue and it is often sufficient to end with the words of the interviewee, particularly if they have made an amusing or strongly assertive point.

After the interview

The interviewer should feel that it has been an enlightening experience that has provided a contribution to the listener's understanding and appreciation of both the subject and the interviewee. If the interview has been recorded, it should be immediately checked by playing back the last 15 seconds or so. No more, otherwise the interviewee, if they are able to hear it, is sure to want to change something and one embarks on a lengthy process of explanation and reassurance. The editorial decision as to the content of the interview as well as the responsibility for its technical quality rests with the interviewer. If, for any reason, it is necessary to re-take parts of a recording, it is generally wise to adopt an entirely fresh approach rather than attempt to recreate the original. Without making problems for the later editing, the questions should be differently phrased to avoid an unconscious effort to remember the previous answer. This amounts to having had a full rehearsal and will almost certainly provide a stale end product. The interviewee who is losing track of what is going into the final piece is also liable to remark ‘… and as I've already explained …’ or ‘… and as we were saying a moment ago …’. Such references to material which has been edited out will naturally mystify the listener, possibly losing concentration on what is currently being said.

If the interview has been recorded, the interviewee will probably want to know the transmission details. If the material is specific to an already scheduled programme, this information can be given with some confidence. If, however, it is a news piece intended for the next bulletin, it is best not to be too positive lest it be overtaken by a more important story and consequently held over for later use. Tell the interviewee when you hope to broadcast it, but if possible avoid total commitment.

Thank the interviewee for their time and trouble and for taking part in the programme. If a journey to the studio is involved, it may be normal to offer travelling expenses or a fee according to station policy. Irrespective of how the interview has gone, professional courtesy at the closing stage is important. After all, you may want to talk again tomorrow.

Style

Evidence suggests that political interviewing reflects the conduct of government nationally. If government and opposition are engaged in hard-hitting debate, with individuals making not only party but personal points, then the media will assume this same style. If, however, opposition views are generally suppressed – or in some cases may not exist at all – then ministers will not expect, and may not allow, any challenge from the media.

Different cultures, different nations, have quite diverse views about authority, even when it has been elected by popular vote. In many places, broadcasters may not interview a government minister without first supplying the questions to be asked. In some, it is the minister who provides the questions – a practice hardly in the public interest.

In the West, where authority of any kind is not held in particularly high regard, radio and television interviewing is frequently directly challenging, especially of publicly answerable figures. It should not, however, adopt a superior tone nor become a personal confrontation between interviewer and interviewee. The first sign of this is the interviewer making assertions in order to score points instead of asking questions. The producer must vigorously analyse interviewing style to cut short such tendencies that quickly attract public criticism as the media overreaching itself.

Interviewing ‘cold’

One of the more challenging aspects of interviewing is in the long sequence programme, such as a breakfast show, where a number of interviewees have been lined up and brought to the studio. The producer/interviewer has little or no opportunity to prepare with each person beforehand. The situation can be improved either through the use of music to give two or three minutes’ thinking time, or by having two presenters interviewing alternately. One essential is to have adequate research notes on each interviewee provided by a programme assistant.

If a presenter is meeting a guest for an immediate interview, the basic information that he or she needs is:

![]() Topic title

Topic title

![]() The person's name

The person's name

![]() Their position, role, job, status, etc.

Their position, role, job, status, etc.

![]() The key issue at stake

The key issue at stake

![]() This person's view of the issue – with actual quotes if possible

This person's view of the issue – with actual quotes if possible

![]() Notes on possible questions or approaches, what other people with different views have said.

Notes on possible questions or approaches, what other people with different views have said.

This kind of interviewing, jumping as it does from subject to subject in a quite unrelated way, calls for great flexibility of mind. Its danger is one of superficiality, where nothing is dealt with in depth or comes to a satisfactory conclusion: ‘… I'm afraid we'll have to leave it there because of time.’

The situation is compounded when the interviewee is at the other end of a telephone and can't be seen. Judging the appropriate style is difficult, rapport between the interviewer and interviewee is slight, the result can feel distant and cold, and the need to press on with the running order can make a hurried ending seem rude as far as the listener is concerned – unaware of studio pressures. All these are factors that the producer of the programme should evaluate. The programme may be fast moving, but is it superficial? It might cover good topics but is it essentially lightweight? Is it brisk at the expense of being brusque?

Interviewing through a translator

News in particular may involve interviewing someone who does not speak your own language. When the interview is ‘live’, there is no option but to go through an interpreter with the somewhat laborious process of sequential translation – so keep the questions short and simple:

‘When were the soldiers here?’

‘What has happened to your home?’

‘Why did they destroy the village?’

‘What happened to your family?’

Depending of course on the circumstances, answers even in another language can communicate powerfully. The translation provides the content of what is said but the replies themselves will define the spirit and strength of feeling in a crisis situation. If the interview is recorded, then simultaneous translation is possible through subsequent dubbing and editing. The first question is put, the reply begins and is faded down under the translation. The second question is followed by the translation of the second answer, and so on. It is good to have snatches of the interviewee's voice occasionally, especially in a long interview, as a reminder that we are using an interpreter. What is totally removed in the editing is the translation of the interviewer's questions. Naturally, it is best to use a translator's voice similar to that of the interviewee, i.e. a man for a man, or a young girl for a young girl, etc. While it is not always possible to do this in the news context, it should be carefully considered for a documentary or feature programme.

Location interviews

The businessman in his office, the star in her dressing room, the worker in the factory or out of doors – all are readily accessible with a portable recorder and provide credible programming with atmosphere. Yet each may pose special problems of noise, interruption and right of access – difficulties also inherent in the vox pop – see Chapter 7.

To remain legal, the producer must observe the rules regarding public and private places. Permission is usually required to interview inside a place of entertainment, business premises, a factory, shop, hospital or school. In this last case, it is worth remembering that consent of parents or a guardian should normally be sought before interviewing anyone under the age of 16. Working in a non-public area also means that if a broadcaster is asked to leave it is best to do so – or else run the risk of a charge of harassment or trespass.

In any room other than a studio, the acoustic is likely to be poor, with too much reflected sound. It is possible to overcome this to an acceptable degree by avoiding hard, smooth surfaces such as windows, desktops, vinyl floors or plastered walls. A carpeted room with curtains and other furnishings is generally satisfactory, but in unfavourable conditions the best course is to work closer to the microphone, while also reducing the level of input to the recorder.

The same applies to locations with a high level of background noise. Nevertheless, the machine shop or aeroplane cockpit need present no insuperable technical difficulty; again, the answer is to work closer to the mic and reduce the record level. This will sufficiently discriminate between the foreground speech and the background noise. A greater problem arises where the sounds are intermittent – an aircraft passing overhead, a telephone ringing or clock striking. At worst, these may be so overwhelming as to prevent the interview from being audible, but even if this is not the case, sudden noises are a distraction for the listener that a constant level of background is not. Background sounds which vary in volume and quality can also represent a considerable problem for later editing – a point interviewers should remember before they start. The greatest difficulty in this respect arises when an interview has been recorded against a background of music. It is then almost impossible to edit.

Only the very experienced should attempt interviewing using a stereo microphone – and it should then be fixed with a mic stand. Even small amounts of movement cause an apparent relocation of the environmental sounds, with the consequent disorientation of the listener. Static stereo mics are good for recording location effects, but interviewing almost always calls for a hand-held mono omnidirectional mic or two small clip-on personal mics. In this latter case, the stereo recording should be re-mixed on playback, with some overlap between the two channels to provide the desired spatial relationship.

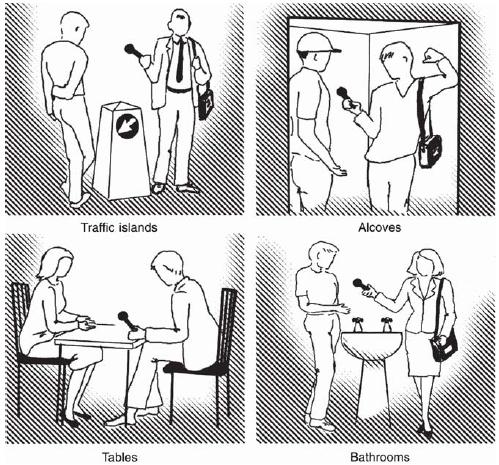

Figure 6.1 Some interviewing situations to avoid. These would be noisy, acoustically poor, or at least asymmetrical, or physically awkward

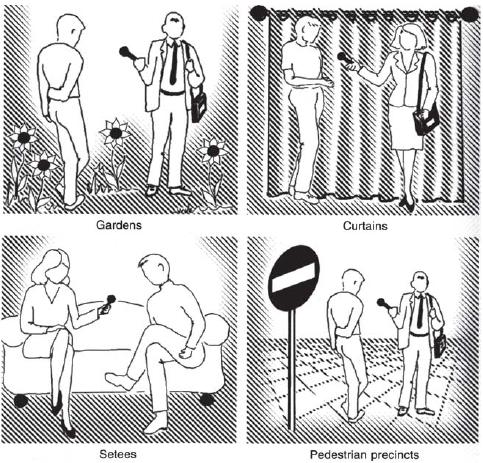

Figure 6.2 Some good places for location interviews. These provide a low or at least a constant background noise, acoustically absorbent surroundings or a comfortable symmetry

It is generally desirable for location interviews to have some acoustic effect or background noise and only practical experience will indicate how to achieve the proper balance with a particular type of microphone. When in doubt, priority should be given to the clarity of the speech.

As with the studio interview, the discussion beforehand is aimed at putting the interviewee at ease. When outside, using a portable recorder, part of this same process is to show how little equipment is involved. The microphone and machine should be assembled, made ready and checked during this preliminary conversation. It is important to handle these items in front of the interviewee and not spring the technicalities at the last moment. Before starting, it is advisable to test the system by ‘taking level’, i.e. by recording some brief conversation to hear the relative volume of the two voices.

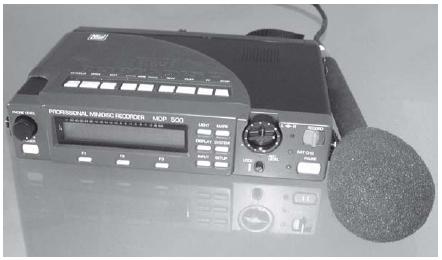

Figure 6.3 The HHB Portadisc MiniDisc recorder. With its own basic editing facility, the audio can be transferred to a laptop on location and the signal sent to the base station by e-mail

Figure 6.4 A sketch of a typical solid state recorder. With no moving parts it is especially robust and is downloaded simply to a laptop or audio workstation computer

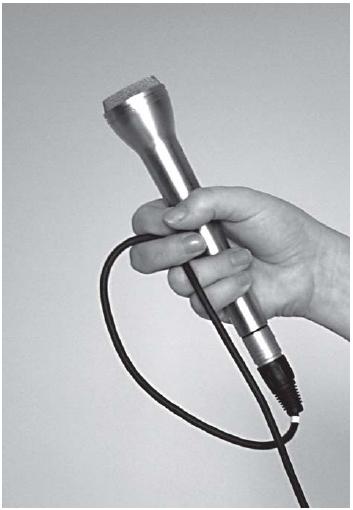

If the microphone is to be hand-held, the cable should be looped around the hand, not tightly wrapped round it, so that no part of the cable leading to the recorder is in contact with the body of the microphone. This prevents any movement in the cable from making itself heard as vibration in the microphone. The mic should be out of the eyeline at a point where it can remain virtually stationary throughout. Only in conditions of high background noise should it be necessary to move the mic alternately towards interviewer and interviewee. Even so, this is preferable to the use of an automatic gain control (AGC) on the machine, which affects the speaker's voice and background noise together, i.e. it does not discriminate between them as microphone movement does. AGC should therefore be switched ‘out’ and any noise reduction system, e.g. Dolby, switched ‘in’. A satisfactory playback of this trial recording is the final check before beginning the interview.

Figure 6.5 The microphone cable is formed into two loops. The loop round the finger is kept away from the microphone case to prevent extraneous noises, commonly known as mic rattles, being passed along the cable. The windshield helps to prevent wind noise and voice ‘pops’

Some further rules in the use of portable recorders:

1 Where necessary, check the ability of the machine to work in unusual conditions, e.g. bumpy vehicles, high humidity, electrical radiation or magnetic fields, or at low temperature; or its suitability for specialist functions, such as recording in a coalmine.

2 Always check the machine and its microphone before leaving base – record and replay.

3 If there is any doubt about the state of electrical charge of the machine's own cells, take spare batteries.

4 Always use a microphone windshield when recording out of doors.

5 Do not leave a recorder unattended, where it can be seen, even in a locked car.

6 Where appropriate, use the best quality recording materials – flash cards, discs, tape or ‘chrome’ type cassettes.

7 Ensure that rechargeable cells are put back on charge after use.

The triangle of trust

The whole business of interviewing is founded on trust. It is a three-way structure involving the interviewer, the interviewee and the listener.

The interviewee trusts the interviewer to keep to the original statement of intent regarding the subject areas and the context of the interview, and also to maintain both the spirit and the content of the original in any subsequent editing. The interviewer trusts the interviewee to respond to questions in an honest attempt to illuminate the subject. The listener trusts the interviewer to be acting fairly in the public interest without any secret collusion between the interviewer and the interviewee. The interviewee trusts the listener not to misrepresent what is being said and to understand that, within the limitations of time, the answers are the truth of the matter.

This ‘triangle of trust’ is an important constituent not only of the media's credibility, but of society's self-respect as a whole. Should one side of the triangle become damaged – for example, listeners no longer trusting broadcasters, interviewees no longer trusting interviewers, or neither having sufficient regard for the listener – there is a danger that the process will be regarded simply as a propaganda exercise. Under these conditions it is no longer possible to distinguish between ‘the truth as we see it’ and ‘what we think you ought to know’. Consequently, the underlying reason for communication begins to disappear, thereby reducing broadcasting's democratic contribution. The fabric of society is affected. This is to take an extreme view, but every time a broadcaster misrepresents, every time an interviewee lies or a listener disbelieves, we have lost something of genuine value.