8

Cues and links

The information needed to accompany a recorded interview or other programme insert has two quite separate functions. The first is to provide studio staff with the appropriate technical data. The second is to introduce the item for the listener so that it makes sense in its context.

The general rules concerning cue material – to be interesting, to grab the listener and to be informative – apply equally to the links between items in a sequence programme and to the introductory announcements given to whole programmes.

Information for the broadcaster

Before a recorded programme or item can reach the air, the producer, presenter or studio operational staff require certain information about it. Typically known as an ‘audio label’, this is generated by the computer system as the item is downloaded for editing and subsequent replay. In any given system, this appears in a standard format and provides details of:

![]() the name of the piece, otherwise known as its slug or catchline

the name of the piece, otherwise known as its slug or catchline

![]() what the item is – interview, actuality or voice piece, etc.

what the item is – interview, actuality or voice piece, etc.

![]() the initials of the reporter/speaker

the initials of the reporter/speaker

![]() the ‘in’ and ‘out’ cues of the item as recorded

the ‘in’ and ‘out’ cues of the item as recorded

![]() the duration, i.e. running time, of the item

the duration, i.e. running time, of the item

![]() the intended date of transmission.

the intended date of transmission.

When recording an insert, the reporter will generally introduce the piece with some background material about where it is being done, who is involved and the basics of the story. This is later edited off, but it enables the producer or editor of the programme to write the introductory cue to the item which the programme's presenter will read. This is typed into the same file as the audio which, after editing, can be transferred to a ‘hotbox’ or transmission slot ready to be played on-air. Any item is also likely to have a ‘back-announcement’. It's clearly important to have a means of preventing unedited material from appearing here, and it is up to the producer to see that only material ready for transmission arrives in the final running order.

When retrieving an item from the computer store, it is necessary to know its precise name or slug. To help in this, some systems give every item a number.

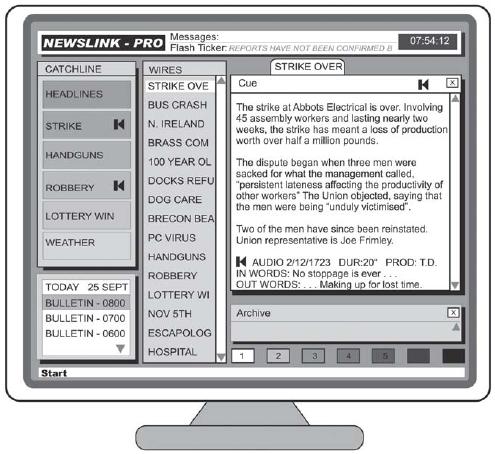

Figure 8.1 News screen. This system provides information needed by the newsroom and the on-air studio. The column on the left shows the bulletin running order and which stories have audio inserts. Script and cues appear on the right. ‘Messages’ at the top are sent to a specific screen – like visual talkback. ‘Flash Ticker’ is information to the whole system

The studio presenter now has a clear indication of how to introduce the item. It may be necessary to alter words to suit a personal style, but the good cue writer will write in a way that fits the specific programme.

Typically, the interviewer's first question is removed from the recording and transferred to the introduction so that the insert begins with the first answer. This style is a very common form of cue, but it is only one of many and it should not be overused, particularly within a single programme. It is easy for cues to become mechanical – to ‘write in a rut’. It is important to search for fresh approaches, and some are given in later examples.

Information for the listener

There is an art to writing good cue material. The piece of writing which introduces an item has three functions for the listener. It must be interesting, act as a ‘signpost’ and be informative.

The information must be interesting. The first sentence should contain some point to which the listener can relate. It should be written in response to likely questions: ‘What is the purpose of this interview?’ ‘Why am I broadcasting this piece?’ Having found the most interesting facet – the ‘angle’ most relevant to the listener – the writer starts from that. But more than this, it should be relevant to as many listeners as possible. It should not be written so as to exclude people. To take a local example:

| Not: | There's a big hole in the road at the corner of Campbell Street and the Broadway. |

| But: | They are digging up the road again. Everywhere you go traffic is diverted by a hole with workmen in it. What's going on? For example, at the corner of … |

The first intro will only interest people who drive down Campbell Street. The second is aimed at all road users, pedestrians too. To draw people in, write from the general to the particular. Another approach is to ask the occasional question as an attempt to involve the listener in a subconscious response.

A cue is a signpost and should make a promise about what is to follow. Having gained the listener's interest, it is then important to satisfy some expectations.

The introduction must be informative. One purpose of an introduction is to provide the context within which the item may be properly understood. There may have to be:

1 A summary of the events leading up to or surrounding the story.

2 An indication of why the particular interviewee was chosen.

3 Additional facts to help the listener's understanding. It may be necessary to clarify technical terms and jargon, or to explain any background noise or sounds which would otherwise distract the listener.

4 The name of the interviewer/reporter.

This last piece of information, generally the last words of the cue, can become a dreadful cliché:

‘Our reporter, John Benson, has the details.’

This is a common introduction to reporter packages and wraps, and if overdone becomes as boring as the ‘and he asked her’ introductions for interviews. Cue writing therefore needs a fertile imagination in order to avoid predictable repetition.

Unless the interview or voice piece is very short, say less than a minute, it will be necessary to repeat after an interview the information about the interviewee. There is a high probability that the listener is not wholly committed to the programme and heard the introduction only superficially, despite a compellingly interesting opening line. The listener's full attention frequently becomes engaged only during the interview itself. Having become fascinated or outraged, it is afterwards that you want to know the name of the interviewee and their qualification for speaking.

Radio is prone to fashion and there has been a tendency for the ‘back-announcement’ to be omitted. It's said that it slows the programme down. It is true that a ‘backward-pointing’ signpost may have such an effect, whereas introductions help to drive the programme forward. However, the argument in favour of a back-announcement puts listener information above programme pace. It also helps to give the impression that the presenter has been listening. Without some reference to the interview, the presenter who simply continues with the next item can sound discourteous. Broadcasters should remember that, to the listener, pre-recorded items are people rather than discs or computer playouts. They should therefore be referred to as if they had actually taken part in the programme.

The practice of omitting the back-announcement is probably an example of radio being influenced by television. In vision, it is possible to superimpose on an interview a caption giving the name and qualification of the interviewee. This can happen at any time throughout a piece and makes a back-announcement unnecessary. The two channels of television information, sound and vision, can be used simultaneously for different purposes. This is not the case with radio, where a statement of the interviewee's name is often the simplest and most logical way of ‘re-informing’ the listener.

Two further examples will illustrate the functions of cue material – that is, to obtain the listener's interest, provide context, explain background noise, clarify technicalities and to ‘back-announce’.

Example 1

When a recording is made against background noise, it is useful to begin the piece with two or three seconds of the sound alone. The insert can be started before the cue and faded up under speech so that its words begin neatly after the introduction. Similarly, at the end of the insert, the background noise is faded down behind the presenter's back-announcement. Such a technique is preferable to the jarring effect of ‘cutting’ on to noise.

In the interests of fairness and objectivity, such an item would invariably need to be followed and ‘balanced’ by a management view of the situation.

Example 2

ANNCT: |

Space research and your kitchen sink. It seems an unlikely combination, but the same advanced technology which put man on the moon has also helped with the household chores. |

For example, the non-stick frying pan uses a chemical called poly-tetra-fluoro-ethylene (Pron: Poli-tetra-flŏrō-éthileen). Fortunately, it's called PTFE for short. Used now for kitchen pans, this PTFE was developed for the coating of hardware out in space. |

|

Dr John Hewson of the National Research Council explains. |

|

CUE IN: |

We've known about PTFE for some time … |

CUE OUT: |

… always looking to the future. |

Duration 3′17″ |

|

ANNCT: |

Dr Hewson |

In this case the cue had the job of explaining what PTFE is. It was referred to in the interview without clarification, so the listener has to be prepared for the term. The introductory cue is a great way of solving any problem of this sort in a pre-recorded item.

The last name in the cue is generally – but not always – the first voice on the insert. To cue the ‘wrong’ person is confusing. For example: ‘Our reporter Bill West has been finding out how the building work is going.’ The voice that follows is assumed to be that of Bill West; if it is actually the site manager, it may be some time before the listener realizes the fact.

In addition, therefore, to the several functions of cue material, the writer seeks both variety and a lack of ambiguity. Cues and links that are well thought out will make a real difference in lifting a programme above the rest. It may take preparation time, but it will be time well spent.

Links

What do you say between items? One must get away from the ‘that was, this is’ approach. The last item may need an explanatory back-announcement and the real question is whether there is a logical progression between that and the next item. If not, because you are going into the weather forecast, then it's better not to try and contrive one. On the other hand, it helps the programme flow if there is a natural and easy way of moving from one scene to the next. Do the items have anything in common? Consider the function of mortar in building a house. Does it keep the bricks apart or hold them together? It does both, of course, and so it is with the presenter. Rather than make the programme seem jerky and disconnected, presenters do well to make such transitions as smooth as possible – even by going into an ident or time check.

Some presenters do well to ad lib, to do everything off the cuff, but it has to be said that for most of us the preparation of interesting, informative, humorous, provocative, friendly or insightful current remarks or comments in the links takes thinking about. This is where the style of the programme comes from. The links more than anything else give substance rather than waffle.