11

Phone-ins

Critics of the phone-in describe it as no more than a cheap way of filling airtime and undoubtedly it is sometimes used as such. But like anything else, the priority it is accorded and the production methods applied to it will decide whether it is simply transmitter fodder or whether it can be useful and interesting to the listener. ‘It's Your World’ on the BBC's World Service has at least the potential for putting anyone anywhere in touch with a major international figure to question policy and discuss issues of the day.

Through public participation, the aim of a phone-in is to allow a democratic expression of view and to create the possibility of community action. An important question, therefore, is to what extent such a programme excludes those listeners who are without a telephone. Telephone ownership can vary widely between regions of the same country, and the cities are generally far better served than the rural areas. Per head of population, North America has more telephones than anywhere else in the world. It follows that to base programmes simply on the American or Canadian practice may be misleading. It is a salutary reminder that 50 per cent of the world's population has never used a phone. It's the same with ‘send us an e-mail …’ or ‘see our website …’ – for many this is an excluding suggestion.

So, it is possible to be over-glib with the invitation: ‘… if you want to take part in the programme just give us a ring on …’. Cannot someone take part simply by listening? Or to go further, if the aim is public participation, will the programme also accept letters, or people who actually arrive on the station's doorstep? The little group of people gathered round the door of an up-country studio in Haiti, while their messages and points of view were relayed inside, remains for me an abiding memory of a station doing its job.

It is especially gratifying to have someone, without a phone at home, go to the trouble of phoning from a public pay phone. To avoid losing the call when the money runs out, the station should always take the number and initiate such calls as are broadcast on a phone-back basis.

Technical facilities

When inviting listeners to phone the programme, it is best to have a special number rather than take the calls through the normal station telephone number, otherwise the programme can bring the general telephone traffic to a halt. The technical means of taking calls have almost infinite variation, but the facilities should include:

1 Off-air answering of calls.

2 Acceptance of several calls – say four or five simultaneously.

3 Holding a call until required, sending the caller a feed of cue programme.

4 The ability to take two calls simultaneously on the air.

5 Origination of calls from the studio.

6 Picking up a call by the answering position after its on-air use.

Programme classification

The producer of a phone-in must decide the aim of the programme and design it so that it achieves a particular objective. If the lines are simply thrown open to listeners, the result can be a hopeless muddle. There are always cranks and exhibitionists ready to talk without saying anything, and there are the lonely with a real need to talk. Inexpert advice given in the studio will annoy those listeners who know more about the subject than the presenter, and may actually be harmful to the person putting the question. By adequate screening of the incoming calls in line with the programme policy, the producer limits the public participation to the central purpose of the show.

Types of phone-in include:

1 The open line – conversation with the studio presenter.

2 The specific subject – expert advice on a chosen topic.

3 Consumer affairs – a series providing ‘action’ advice on detailed cases.

4 Personal counselling – problems discussed for the individual rather than the audience.

The open line

A general programme where topics of a non-specific nature are discussed with the host in the studio. There need be no theme or continuity between the calls, but often a discussion will develop on a matter of topical interest. The one-minute phone-in, or ‘soapbox’, works well when callers are allowed to talk on their own subject for one minute without interruption, providing they stay within the law.

Support staff

There are several variations on the basic format, in which the presenter simply takes the calls as they come in. The first of these is that the lines are answered by a programme assistant or secretary, who ensures that the caller is sensible and has something interesting to say. The assistant outlines the procedure: ‘please make sure your radio set is not turned on in the background’ (to avoid acoustic ‘howl-round’); ‘you'll hear the programme on this phone line and in a moment X (the presenter) will be talking to you’. The call is then held until the presenter wants to take it. Meanwhile, the assistant has written down the details of the caller's name and the point he or she wishes to make, and this is passed to the presenter. Since they are in separate rooms studio talkback will be used or, better, a third person involved to pass this information. This person is often the producer, who will decide whether or not to reject the call on editorial or other grounds, to take calls in a particular order, or to advise the presenter on how individual calls should be handled. If the staffing of the programme is limited to two, the producer should take the calls, since this is where the first editorial judgement is made. A computer is useful for providing visual talkback between call-taker and presenter, so that the presenter can be given a considerable amount of advance information about each call.

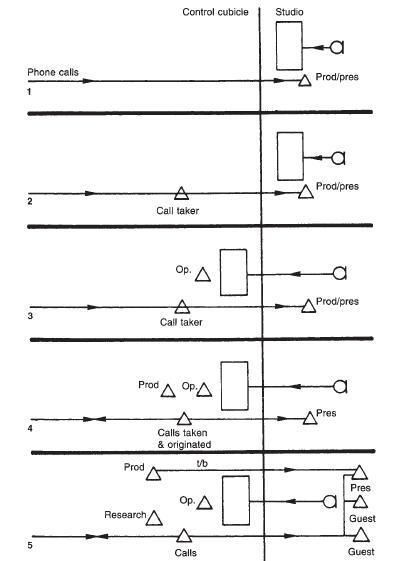

Figure 11.1 Staffing a phone-in. 1. The total self-op. The presenter takes the calls. 2. A ‘call-taker’ screens the calls and provides information to the presenter in advance of each call. 3. An operator controls all technical operation, e.g. discs, levels, etc., while the producer/presenter concentrates on programme content. 4. Separate producer in the control area to make programme decisions, e.g. to initiate ‘phone-out’ calls. 5. Guest ‘experts’ in the studio with research support available

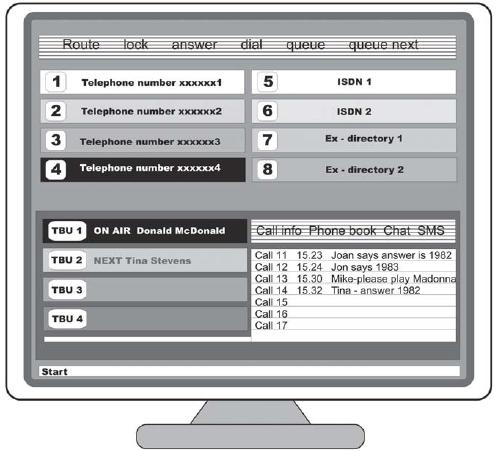

Figure 11.2 Phone-in screen. Incoming calls are taken by the producer on lines 1–4. ISDN lines come from other studios and two ex-directory lines are for phone-out. The presenter is currently talking with Donald McDonald and knows that Tina Stevens is waiting with the answer ‘1982’

Choosing the calls

The person vetting the calls quickly develops an ear for the genuine problem, the interesting point of view, the practical or the humorous. Such people converse. They have something to say but can listen as well as speak, they tend to talk in short sentences and respond quickly to questions put to them. These things are soon discovered in the initial off-air conversation. Similarly, there are people who one might prefer not to have on the programme:

![]() the ‘regulars’ who are always phoning in

the ‘regulars’ who are always phoning in

![]() the abusive, perverted, offensive or threatening caller

the abusive, perverted, offensive or threatening caller

![]() the over-talkative and uninterruptible

the over-talkative and uninterruptible

![]() the boring, dull or slow

the boring, dull or slow

![]() those with a speech defect, unless the programme is specifically designed for this topic

those with a speech defect, unless the programme is specifically designed for this topic

![]() those with speech patterns or accents which make intelligibility particularly difficult

those with speech patterns or accents which make intelligibility particularly difficult

![]() the sycophantic, who only want to hear you say their name on the air.

the sycophantic, who only want to hear you say their name on the air.

Of course, the programme must have the idiosyncratic as well as the ‘normal’, and perhaps anger as well as conciliation. But without being too rude there are many ways of ending a conversation, either on or off the air:

‘I'm sorry, we had someone making that point yesterday …’

‘I can't promise to use your call, it depends how the programme goes …’

‘There's no one here who can help you with that one …’

‘I'm afraid we are not dealing with that today …’

‘This is a very bad line, I can't hear you …’

‘You are getting off the subject, we shall have to move on …’

‘We have a lot of calls waiting …’

Or simply:

‘Right, thank you for that. Goodbye …’

The good presenter will have the skill to turn someone away without turning them off, but in moments of desperation it is worth remembering that even the most loquacious person has to breathe.

The role of the presenter

The primary purpose of the programme is democratic – to let people have their say and express their views on matters which concern them. It is equivalent to the ‘letter to the editor’ column of a newspaper or the soapbox orator stand in the city square. The role of the presenter or host is not to take sides – although some radio stations may adopt a positive editorial policy – it is to stimulate conversation so that the matter is made interesting for the listener. The presenter should be well versed in the law of libel and defamation, and be ready to terminate a caller who becomes obscene, overtly political, commercial or illegal in accordance with the programme policy.

Very often, such a programme succeeds or fails by the personality of the host presenter – quick thinking with a broad general knowledge, interested in people, well versed in current affairs, wise, witty, and by turn as the occasion demands genial, sharp, gentle, possibly even rude. All this combined with a good characteristic radio voice, the presenter is a paragon of broadcasting.

Presenter style

In aural communication, information is carried on two distinct channels – content (what is said) and style (how it is said). They should both be under the speaker's control and, to be fully effective, one should reinforce the other. Due however to stress, it is not always easy, for example, to make a light point lightly. Without intention, it is possible to sound serious, even urgent, and the effect of making a light point in a serious way is to convey irony. The reverse, that of making light of something serious, can sound sarcastic. The problem, therefore, is how to appear natural in a tense situation. It may be useful to ask yourself ‘how should I come over?’

The following list may be helpful:

1 To be sincere – say what you really feel and avoid acting.

2 To be friendly – use an ordinary tone of voice and be capable of talking with an audible smile. Avoid ‘jargon’ and specialist or technical language.

3 To appear human – use normal conversational language and avoid artificial ‘airs and graces’. Admit when you do not know the answer.

4 To be considerate – demonstrate the capacity to understand views other than your own.

5 To be helpful – offer useful, constructive practical advice.

6 To appear competent – demonstrate an appreciation of the question and ensure accuracy of answers. Avoid ‘waffle’ and ‘padding’.

This, of course, is no different from the ordinary personal contacts made hundreds of times each day without conscious thought. What is different for the broadcaster is that the stress in the situation can swamp the normal human qualities, leaving the ‘colder’ professional ones to dominate. Someone concerned to appear competent will all too easily sound efficient to the point of ruthlessness unless the warmer human characteristics are consciously allowed to surface.

The most valuable quality is credibility. Only when the listener believes the person speaking will they be prepared to take notice or act on what is being said. For this reason, style is initially more important than content.

Reference material

The presenter may be faced with a caller actually seeking practical advice and it is important for the producer to know in advance how far the programme should go in this direction, otherwise it may assume expectations for the listener which cannot be fulfilled. Broadcasters are seldom recruited for their practical expertise outside the medium and there is no reason why they should be expected spontaneously to answer specialist questions. However, the availability in the studio of suitable reference material will enable the presenter to direct the caller to the appropriate source of advice or information. Reference sources may include telephone directories, names and addresses of councillors, members of parliament or other elected representatives, government offices, public utilities, social services, health and education departments, welfare organizations and commercial PR people. This information is usually given on the air, but it is a matter of discretion. In certain cases it may be preferable for the presenter to hand the caller back to the secretary, who will provide the appropriate information individually. If there is a great deal of factual material needed, then a fourth person will be required to do the immediate research, especially if searching the Internet.

Studio operation

At the basic level it is possible for the presenter alone to undertake the operation of the studio control desk. But as facilities are added, it becomes necessary to have a specialist panel operator, particularly where there is no automatic equipment to control the sound levels of the different sources. In this respect, an automatic ‘voice-over’ unit for the presenter is particularly useful, so that when speaking, the level of the incoming call is decreased. It must, however, be used with care if he or she is to avoid sounding too dominating.

Additional telephone facilities

If the equipment allows, the presenter may be able to take two calls simultaneously, so setting up a discussion between callers as well as with the studio. The advice and cooperation of the telephone company may be required prior to the initiation of any phone programme. This is because there may well have to be safeguards taken to prevent the broadcasting function from interfering with the smooth running of the telephone service. These may take the form of limitations imposed on the broadcaster in how the telephone might be used in programmes, or possibly the installation of special equipment either at the telephone exchange or at the radio station.

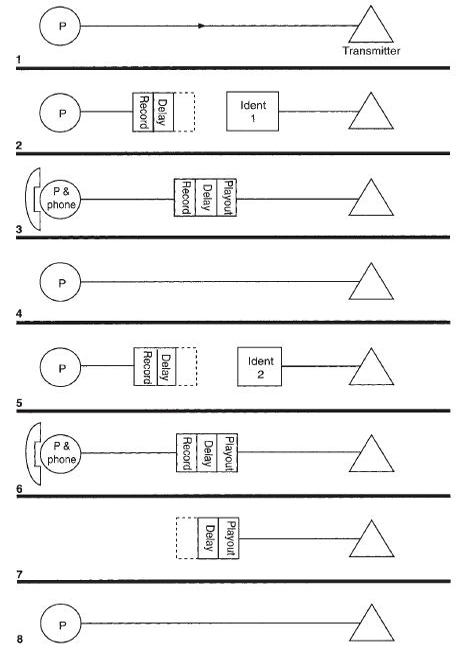

Figure 11.3 The use of delay in a phone-in. 1. The presenter P is fed directly to the transmitter. 2. To introduce a delay, the presenter is recorded and held on a short-term (10-second) storage. The programme output is maintained for this duration by Ident 1. 3. As Ident 1 ends, the programme continues using the recorded playout. The transmission is now 10 seconds behind ‘reality’. 4. If a caller says something that has to be cut, the delayed output is replaced by the presenter ‘live’. 5. To reinstate the delay, the procedure is as in 2, but using a different Ident. 6. The programme continues through the delay device. 7. The presenter brings the programme to an end, allowing the recorded playout to finish the transmission. 8. Normal live presentation

Use of ‘delay’

The listening interest of this type of programme depends to an extent on the random nature of the topics discussed and the consequent possibility of the unexpected or outrageous. There is a vicarious pleasure to be obtained from a programme not wholly designed in advance. But it is up to the presenter to ensure that there is reasonable control. However, as an additional safeguard, it is possible to introduce a delay time between the programme and the transmission – indeed, some radio stations and broadcasting authorities insist on it. Should any caller become libellous, abusive or obscene a delay device, of say 10 seconds, enables that part of the programme to be deleted before it goes on the air. The programme, usually a short-term recording, is faded out and is replaced by the ‘live’ presenter's voice. With a good operator, this substitution can be made without it being apparent to the listener. Returning from the ‘live’ to the ‘delayed’ programme is more difficult, and it is useful to have on hand news, music or other breaks to allow the presenter time to return to another call. If the caller is occasionally using words which the producer regards as offensive, these can be ‘bleeped out’ by replacing them with a tone source as they reach the air. Again, good operation is essential. Overall, however, a radio station gets the calls it deserves and, given an adequate but not oppressive screening process, the calls will in general reflect the level of responsibility at which the programme itself is conducted.

The specific subject

Here, the subject of the programme is selected in advance so that the appropriate guest expert, or panel of experts, can be invited to take part. It may be that the subject lends itself to the giving of factual advice to individual questions – for example, child care, motoring, medical problems, gardening, pets and animals, farming, antiques, holidays, cooking, financial issues or citizens’ rights. Or the programme may be used as an opportunity to develop a public discussion of a more philosophical nature – for instance, the state of the economy, political attitudes, education or religious belief.

A word of warning, however, about giving specific advice.

Doctors should not attempt diagnosis over the phone, much less prescribe drugs in individual cases. What tends to be most useful is general information about illness, the side-effects of drugs, what to expect when you go into hospital, the stages of pregnancy, children's diseases, reclaiming medical costs on social welfare, and so on.

Of course, there will be difficult calls and the producer should discuss a medical programme's policy with guests beforehand, rather than having to decide it live on-air. For example, how will you deal with cancer, AIDS and the terminally ill? What will you do with what appears to be a complaint against a hospital? At what point might you rule out a call as being too embarrassing, disgusting or voyeuristic? When is the caller just sending you up?

The legal phone-in too needs special care, but can provide useful information on a wide range of subjects rooted in actual practice: employment law, motor insurance claims, marriage and divorce, wills, the rights of victims, disputes between landlord and tenant, land claims, house purchase, the responsibilities of children, arguments between neighbours – noise, nuisance, fences, trees, etc. A lawyer, like a doctor, should be wary of providing specific solutions over the phone – the caller is unlikely to give all the facts, especially those not supporting his or her case. There is also a real danger of being used as a second opinion in a case already in front of the courts, or where the caller is dissatisfied with advice already obtained. The professional guest will know when to respond with: ‘I can't comment on your actual case without the details, but in general …’. The point of whether a radio service can be sued for giving wrong advice is of interest here. The answer will be ‘no’, so long as the programme does not try to imitate the private consultation. The producer serves the public best by providing advice of general applicability, illustrating how the law operates in specific areas.

‘Early lines’

In order to obtain questions of the right type and quality, the phone lines to the programme may be opened some time before the start of the transmission – say half an hour. The calls are taken by a secretary or programme assistant, who notes the necessary details and passes the information to the producer, who can then select the calls wanted for the programme. For the broadcast these are originated by the studio on a phone-back basis.

The combination of ‘early’ lines and ‘phone-back’ gives the programme the following advantages:

1 The calls used are not random but are selected to develop the chosen theme at a level appropriate to the answering panel and the aim of the programme.

2 The order in which the calls are broadcast is under the control of the producer and so can represent a logical progression of the subject.

3 The studio expert, or panel, has advance warning of the questions and can prepare more substantial replies.

4 The phone-back principle helps to establish the credentials of the caller and serves as a deterrent to irresponsible calls. The programme itself may therefore be broadcast ‘live’ without the use of any delay device.

5 At the beginning of the programme there is no waiting for the first calls to come in; it can start with a call of strong general interest already established.

6 Poor or noisy lines can be redialled by the studio until a better quality line is obtained.

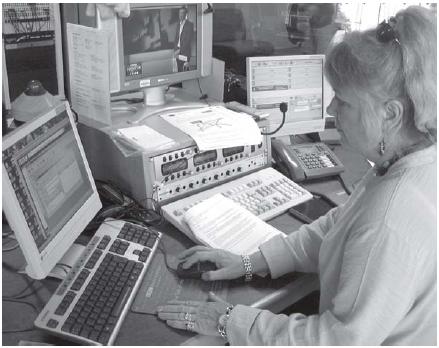

Figure 11.4 A local radio phone-in producer answers calls, phones callers back, selects the calls to put through to the presenter, deals with ISDN, two-ways, and greets guests (Courtesy of BBC Radio Norfolk)

Consumer affairs

The consumer phone-in is related to the ‘specific subject’, but its range of content is so wide that any single panel or expert is unlikely to provide detailed advice in response to every enquiry. As the range of programme content increases, the type of advice given tends to become more general, dealing with matters of principle rather than the action to be taken in a specific case. For example, a caller complains that an electrical appliance bought recently has given persistent trouble – what should they do about it? An expert on consumer legislation in the studio will be able to help distinguish between the manufacturer's and the retailer's responsibility, or whether the matter should be taken up with a particular complaints council, electricity authority or local government department. To provide a detailed answer specific to this case requires more information. What were the exact conditions of sale? Is there a guarantee period? Is there a service contract? Was the appliance being used correctly?

The need to be fair

Consumer affairs programmes rightly tend to be on the side of the complainant, but it should never be forgotten that a large number of complaints disintegrate under scrutiny and it is possible that such fault as there is lies with the user. Championing ‘the little man’ is all very well, but radio stations have a responsibility to shopkeepers and manufacturers too. Once involved in a specific case the programme must be fair, and be seen to be fair. Two further variations on the phone-in help to provide this balance:

1 The phone-out. A useful facility while taking a call is to be able to originate a second call and have them both on the air simultaneously. In response to a particular enquiry, the studio rings the appropriate head of sales, PR department or council/government official to obtain a detailed answer, or at least an undertaking that the matter will be looked into.

2 The running story. The responsibility to be fair often needs more information than the original caller can give or than is immediately available and an enquiry may need further investigation outside the programme. While the problem can be posed and discussed initially, it may be that the subject is one which has to be followed up later.

Linking programmes together

Unlike the ‘specific subject’ programme, which is an individual ‘one-off’, the broad consumer affairs programme may run in series – weekly, daily or even morning and afternoon. A complex enquiry may run over several programmes and while it can be expensive of the station's resources, it can also be excellent for retaining and increasing the audience. For the long-term benefit of the community, and the radio station, the broadcaster must be sure that such an investigation is performing a genuine public service.

As with all phone-in programmes, consideration should be given to recording the broadcast output in its entirety as a check on what was said – indeed, this may be a statutory requirement imposed on the broadcaster. People connected with a firm that was mentioned but who heard of the broadcast at second-hand may have been given an exaggerated account of what transpired. An ROT (recording off transmission) enables the station to provide a transcript of the programme and is a wise precaution against allegations of unfair treatment or threat of legal proceedings – always assuming, of course, that the station has been fair and responsible!

Personal counselling

With all phone-in programmes, the studio presenter is talking to the individual caller but has constantly to bear in mind the needs of the general listener. The material discussed has to be of interest to the very much wider audience who might never phone the station but who will identify with the points raised by those who do. This is the nature of broadcasting. However, once the broadcaster decides to tackle personal problems, sometimes at a deeply psychological and emotionally disturbing level, one cannot afford to be other than totally concerned for the welfare of the individual caller. For the duration, the responsibility to the one exceeds that to the many. Certainly, the presenter cannot terminate a conversation simply because it has ceased to be interesting or because it has become too difficult. Once a radio service says ‘bring your problems here’, it must be prepared to supply some answers.

This raises important questions for the broadcaster. Are we exploiting individual problems for public entertainment? Is the radio station simply providing opportunities for the aural equivalent of the voyeur? Or is there sufficient justification in the assumption that, without even considering the general audience, at least some people will identify with any given problem and so be helped by the discussion intended for the individual? It depends, of course, on how the programme is handled, the level of advice offered and whether there is a genuine attempt at ‘caring’.

To what extent will the programme provide help outside its own airtime? The broadcaster cannot say ‘only bring your depressive states to me between the transmission times of 9 and 11 at night’. Having offered help, what happens if the station gets a call of desperation during a music show? The radio station has become more than simply a means of putting out programmes, it has developed into a community focus to which people turn in times of personal trouble. The station must not undertake such a role lightly, and it should have sufficient contacts with community services that it can call on specialist help to take over a problem which it cannot deal with itself. But how can the programme director ensure that the advice given is responsible? Because of all the types of programme that a station puts out, this is the one where real damage may be done if the broadcaster gets it wrong. Discussing problems of loneliness, marriage and sex, or the despair of a would-be suicide, has to be taken seriously. It is important to get these callers to talk and to enlist their support for the advice given, and for this purpose a station needs its trained counsellors.

The presenter as listener

As with all phone-in programmes, the presenter in the studio cannot see the caller. He or she is denied all the usual non-verbal indicators of communication – facial expression, gesture, etc. This becomes particularly important in a counselling programme, when the caller's reaction to the advice given is crucial. The person offering the advice must therefore be a perceptive listener – a pause, a slight hesitation in what the caller is saying, may be enough to indicate whether they are describing a symptom or a cause, or whether they've yet got to the real problem at all. For this reason, many such programmes will have two people in the studio: the presenter, who will take the call initially and discuss the nature of the problem; and the specialist counsellor, who has been listening carefully and who takes over the discussion at whatever stage it is felt necessary. Such a specialist may be an expert on marriage guidance, a psychiatrist, a minister of religion or doctor.

Non-broadcasting effort

Personal counselling or advice programmes also need off-air support – someone to talk further with the caller or to give names, addresses or phone numbers which are required to be kept confidential. The giving of a phone number over the air is always a signal for some people to call it, so blocking it as an effective source for the one person the programme is trying to help. Again, the broadcaster may need to be able to pass the problem to another agency for the appropriate follow-up.

The time of day for a broadcast of this type seems to be especially critical. It is particularly adult in its approach and is probably best at a time when it may be reasonably assumed that few children will be listening. This indicates a late evening slot – but not so late as to prevent the availability of unsuspected practical help arising from the audience itself.

Anonymity

Often, a programme of this type specializing in personal problems allows callers to remain unidentified. Their name is not given over the air, the studio counsellor referring to them by first name only or by an agreed pseudonym. This convention preserves what most callers need – privacy. It is perhaps surprising that people will call a radio station for advice, rather than ask their family, friends or specialist, simply because they do not have to meet anyone. It can be done from a position of security, perhaps in familiar surroundings where they do not feel threatened.

People with a real problem seldom ring the station in order to parade it publicly – such exhibitionists should be weeded out in the off-air screening and helped in some other way. The genuine seeker of help calls the station because it's already known as a friend and as a source of unbiased personal and private advice. He or she knows that it's not necessary to act on the advice given unless they agree with it and want to. This is a function unique to radio broadcasting. It is perhaps a sad comment when a caller says ‘I've rung you because I can't talk to anyone about this’, but it is in a sense a great compliment to the radio station to be regarded in this way. As such, it needs be accepted with responsibility and humility.

Phone-in checklist

The following list summarizes what is needed for a phone-in programme:

1 Discuss the programme with the telephone service and resolve any problems caused by the additional traffic which the programme could generate. Do you want all the calls, even the unanswered ones, to be counted?

2 Decide the aim and type of the programme.

3 Decide the level of support staff required in the studio. This may involve a screening process, phone-back, immediate research, operational control and phone-out.

4 Engage guest speakers.

5 Assemble reference material.

6 Decide if ‘delay’ is to be used.

7 Arrange for ‘recording off transmission’.

8 Establish appropriate ‘follow-up’ links with other, outside, agencies.