13

Music programming

The filling of programme hours with recorded music is a universal characteristic of radio stations around the world. This is hardly surprising in view of the advantages for the broadcaster. Computerized music stores, hard disks and CDs represent a readily available and inexhaustible supply of high-quality material of enormous variety that is relatively inexpensive, easy to use and enjoyable to listen to. Many stations allow little or no freedom for presenters in what they choose to play, but some leave it entirely up to the show's host. Most have all the music sources hidden away, to be brought up by the computer keyboard; others play CDs, even vinyl, in the studio. Suffice it to say that there is a wide range of operational practice. Before looking in detail at some of the possible formats and what makes for a successful programme, there are three important preliminaries to consider.

First, the matter of music copyright. Virtually every CD, cassette and music label carries the words: ‘All rights of the producer and of the owner of the recorded work reserved. Unauthorized public performance, broadcasting and copying of this record prohibited.’ This is to protect the separate rights of the composer, publisher, performers and the recording company, who together enabled the disc to be made. The statement is generally backed by law – in Britain the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act (1988). It would obviously be unfair on the original artists if there were no legal sanctions against the copying of their work by someone else and its subsequent remarketing on another label. Similarly, broadcasters, who in part earn their living through the effort of recording artists and others, must ensure that the proper payments are made regarding the use of their work. As part of a ‘blanket’ agreement giving ‘authorized broadcasting use’, most radio stations are required to make some form of return to the societies representing the music publishers and record manufacturers, indicating what has been played. In Britain these are, respectively, the Performing Right Society (PRS) and Phonographic Performance Ltd (PPL). It is the producer's responsibility to see that any such system is carefully followed.

Second, it must be said that, in using records, broadcasters are apt to forget their obligation to ‘live’ music. Whatever the constraints on the individual station, some attempt should be made to encourage performers by providing opportunities for them to broadcast. Many recording artists owe their early encouragement to radio, and broadcasting must regard itself as part of the process that enables the first class to emerge. Having reached the top, performers should be given the fresh challenge which radio brings.

Third, top-flight material deserves the best handling. It is easy to regard a track simply as a ‘thing’ instead of a person. On the air, someone's reputation may be at stake. Basic operational technique must be faultless – levels, accurate talk-overs, fades, etc. Most important is that music should be handled with respect to its phrasing.

Attitudes to music

Music, like speech, comes in sentences and paragraphs. It would be nonsensical to finish a voice piece other than at the end of a sentence, and similarly it is not good practice to fade a piece of music arbitrarily. A great deal of work has gone into its production and it should not be treated like water out of a tap, to be turned off and on at will – not unless the broadcaster is prepared to accept the degradation of music into simply a plastic filler material. The good operator, therefore, will develop an ‘ear’ for fade points. The ‘talk-over’ – an accurately timed announcement that exactly fits the non-vocal introduction of a song – provides a satisfying example of paying attention to such detail. Music handled with respect to its phrasing provides listening pleasure for everyone.

The presenter must accept the responsibility when music and speech are mixed through an automatic voice-over unit or ‘ducker’ so that any speech hurls the music into the background. It has its uses in particular types of high-speed DJ programme, but to use music as a semi-fluid sealant universally applied seems to imply that the programme has cracks which have to be frantically filled!

The broadcaster's attitude to music is often typified by the level of care in the treatment of CDs, cassettes and records. They are worth looking after. This includes – for the stations that have them – an up-to-date library cataloguing system and proper arrangements for withdrawal and return, thus avoiding their being left lying around in the studio or production offices. Many broadcasters who play music professionally have domestic stereo equipment over which they take meticulous care – they would not dream of touching the playing surface of a disc with their fingers.

Recordable CDs can store a wealth of material on their 99 possible tracks, from commercials and station jingles to individual presenter idents and programme inserts. Compilation CDs can be made to collect together the currently favoured music tracks, as well as being an excellent medium for station archives.

The programme areas now discussed in detail are: music formats, requests and dedications, guest programmes, and the DJ show.

Clock format

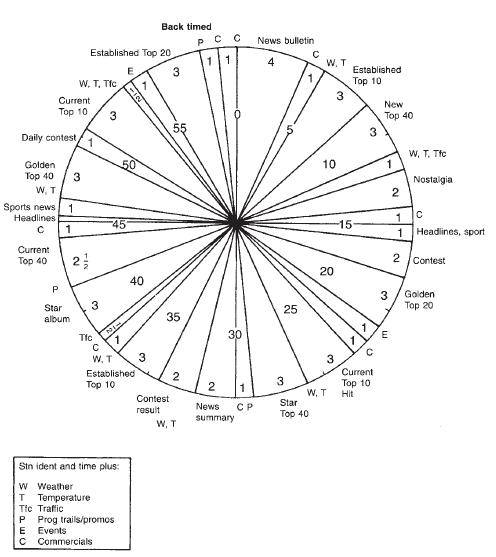

Designing a music programme on a one-hour clockface has several advantages for both the presenter and the scheduler. It enables the producer/ presenter to see the balance of the show between music and speech, types of music, and the spread of commercials; it is a great help in maintaining consistency when another presenter has to take over; and it enables format changes to be made with the minimum of disruption. It is a suitable method to use regardless of the length of the programme. The clock provides a solid framework from which a presenter may depart if need be, and pick up again just as easily. It imposes a discipline but allows freedom.

Starting with the audience, the producer begins by asking questions. Who do I wish to attract? Is my programme to be for a particular age or demographic group? This will obviously affect the music chosen, and a reasonable rule of thumb assumes that the musical taste of many people was formed in their teens. For example, listeners in their forties are likely to appreciate the hits of 25 years ago. Of course, there are many categories of music that have their own specialist format or may be used to contribute to a programme of wider appeal. Beware, however, of creating too wide a contrast – the result is likely to please no one. The basic categories, which contain their own subdivisions, can be listed as follows:

| Top 40 | Classic hits (the last 25 years) |

| Progressive rock | Golden oldies |

| Black soul/funk | Jazz |

| Rap | Folk |

| Hip-hop | Country |

| Rhythm and blues | Latin American |

| Disco-beat | Middle of the road |

| House music | Light classical, orchestral – operetta |

| Adult contemporary | Classical, symphonic – opera, etc. |

Having established the broad category, there are infinite combinations of tempo and sound with which to achieve the essential variety within any chosen consistency:

![]() Sound – rock band, big/small, heavy metal, synthetic.

Sound – rock band, big/small, heavy metal, synthetic.

![]() Tempo – slow, medium, med/bright, upbeat.

Tempo – slow, medium, med/bright, upbeat.

![]() Vocal – male, female, duo, group, newcomer, star.

Vocal – male, female, duo, group, newcomer, star.

![]() Era – thirties, forties, fifties, sixties, seventies, eighties, etc.

Era – thirties, forties, fifties, sixties, seventies, eighties, etc.

![]() Ensemble – big band, string, military band, brass, orchestral, choral.

Ensemble – big band, string, military band, brass, orchestral, choral.

Lengthy formatted programmes need not be constructed to have a strong beginning and end; the skill lies in the presenter providing the listener with a satisfying programme over whatever time-period the show is heard. The breakfast show and drive-time programmes are likely to be heard by many people over a relatively short time-span, perhaps 20–30 minutes. The afternoon output will probably be heard in longer durations. The producer sets out to meet the needs of the total audience – so the two key questions are: Does the plan contain the essential elements in the estimated normal period of listening? Does it contain the necessary variety over a longer time-span?

Figure 13.1 A clock format illustrating the concept of a breakfast time programme on the basis of:

![]() News on the hour, summary on the half-hour, headlines at quarters

News on the hour, summary on the half-hour, headlines at quarters

![]() Eight minutes of advertising in the hour, employing news adjacency

Eight minutes of advertising in the hour, employing news adjacency

![]() Music/speech ratio of about 60:40

Music/speech ratio of about 60:40

![]() Generally MOR sound using current hits, golden or ‘yesteryear’ Top 40, star name and nostalgia tracks

Generally MOR sound using current hits, golden or ‘yesteryear’ Top 40, star name and nostalgia tracks

![]() Speech includes current information, sports news, ‘short’ programme contest and station daily competition

Speech includes current information, sports news, ‘short’ programme contest and station daily competition

Station practice indicates the following guidelines:

![]() Come out of news bulletins on a non-vocal up-tempo sound. Restore the music pace and avoid any unfortunate juxtaposition of news story and lyric.

Come out of news bulletins on a non-vocal up-tempo sound. Restore the music pace and avoid any unfortunate juxtaposition of news story and lyric.

![]() When programming new or unfamiliar music, place solid hits or known material on either side of it – ‘hammocking’ .

When programming new or unfamiliar music, place solid hits or known material on either side of it – ‘hammocking’ .

![]() Spread items of different types evenly up to the hour as well as on the downside.

Spread items of different types evenly up to the hour as well as on the downside.

![]() Mix items of different durations; avoid more than two items of similar length together.

Mix items of different durations; avoid more than two items of similar length together.

![]() Occasionally break up the speech–music–speech sandwich by running tracks back to back, i.e. use the segue or segue plus talk-over.

Occasionally break up the speech–music–speech sandwich by running tracks back to back, i.e. use the segue or segue plus talk-over.

![]() Place regular items at regular times.

Place regular items at regular times.

Computerized selection

Many stations regulate the use of music in a totally systematic way – for example, to prevent the same tracks being used in adjacent programmes. Entering titles as data, a computer is programmed to provide the right mix of material with music styles, performers, composers, etc. appearing at the desired frequency. The scheduling is then in the hands of one of the many types of computer software – SABLE, Selecta, Tune Tracker, MusicMaster, AirTrafficControl or other station system which decides the rotation of items, how many times a track will be played in a given period, and what type and length of music is appropriate for different times of day. The database keeps a history of the music played that not only provides the official music logs, but is the source for answering listener enquiries.

A computerized system is used to generate a weekly playlist which is mandatory for presenters who are given no choice over their music. Less restricting is the playguide. This requires presenters to select a given percentage of their programme from material determined by the programme controller; the remainder they choose themselves. Station policy invariably lays down the extent of individual freedom in the matter of music choice.

Requests and dedications

In presenting a request show it is all too easy to forget that the purpose is still to do with broadcasting. There is a temptation to think only of those who have written in, rather than of the audience at large. Until the basic approach is clarified, it is impossible to answer the practical questions that face the producer. For example, to what extent should the same track be played in successive programmes because someone has asked for it again? Is there sufficient justification in reading out a lengthy list of names simply because this is what appears on the request card? While the basis of the programme is clearly dependent on the initiative of the individual listener who requests a record, the broadcaster has a responsibility to all listeners, not least the great majority who do not write. The programme aims may be summarized:

1 To entertain the general audience.

2 To give especial pleasure to those who have taken the trouble to send a request.

3 To foster goodwill by public involvement.

Programmes are given a good deal of individual character by the presenter who sets the guidelines. The idea may be only to have requests related to birthdays, weddings or anniversaries, or that each request has to be accompanied by a personal anecdote, joke or reminiscence to do with the music requested. References to other people's nostalgia can certainly add to the general entertainment value of the programme. The presenter should be consistent about this and it is important that style does not take over from content, for if the intention of the programme is to play music, it is this rather than speech which remains the central ingredient.

Dedications are often more frequent than requests, i.e. cards not related to a specific piece of music but which can be associated with any item already included in the programme. By encouraging ‘open’ cards of this type, the programme can carry more names, and listeners therefore have a greater chance of hearing themselves mentioned.

Having decided the character and format of the programme, there are essential elements in its preparation.

Choosing music

With music items of two to four minutes each, there will be some eight or nine tracks in each half hour of non-advertising airtime. This allows for about a minute of introduction, signature tunes, etc. Given the volume of letters and cards received, it soon becomes clear to what extent actual requests can be met. The proportion that can be dealt with may be quite small and, assuming that their number exceeds the capacity to play them, a selection process is necessary.

The criteria of selection will include the presenter's desire to offer an attractive programme overall, with a variety of music consistent with the programme policy. It may be limited to the current Top 40, to pop music generally, or it may specifically deal with one area, for example gospel music. On the other hand, the choice may be much wider to include popular standards, light classical music or excerpts from symphonic works. The potential requester should know what kind of music a particular programme offers.

Another principle of selection is to choose requests that are likely to suit the presenter's remarks, i.e. those which will make for an interesting introduction, an important or unusual event, a joke or a particularly topical reference. It is frequently possible to combine requests using comments from a number of cards in order to introduce a single piece of music. The danger here is to become involved in several lists of names which may delight those who like hearing themselves referred to on the air, but which can become boring to the general listener. It is, however, a useful method of including a name check while avoiding a particular choice of music, either because to do so would be repetitious or because it is out of keeping with the programme – or, of course, because the station does not have the named track.

Item order

After selecting the music, a decision has to be made about its sequence. This should not be a matter of chance, for there are positive guidelines in building an attractive programme. ‘Start bright, finish strong’ is an old music hall maxim and it applies here. A tuneful or rhythmic familiar up-tempo ‘opener’ with only a brief speech introduction will provide a good start with which the general listener can identify. A slower piece should follow and thereafter the music can be contrasted in a number of ways: vocal/non-vocal, female vocal/male vocal, group vocal/solo vocal, instrumental/orchestral, slow/fast, familiar/unfamiliar and so on. It is sensible to scatter the very popular items throughout the programme and to limit the material that may be entirely new. Careful placing is required, with slow numbers which need to be followed by something brighter. The order in which music is played, of course, affects all music programmes whether or not they are based on the use of records.

Prefading to time

The last piece of music can be chosen to provide ‘the big finish’ and a suitable finale will often be a non-vocal item. This allows it to be faded in under the presenter's introduction. It may have been timed to end a little before the close of the programme, so leaving room for the final announcements and signature tune. ‘Prefading to time’ (not to be confused with ‘prefade’ – audition or pre-hear) or ‘back timing’ is the most common device for ensuring that music programmes run to time. A closing signature tune will almost certainly be prefaded to time.

In a similar way, items within a programme, particularly a long one, can be subject to this technique to provide fixed points and to prevent the overall timing drifting.

Figure 13.2 Prefading to time. This is the most usual method of ensuring that programmes run to time. In this example, the final disc is 2′40″ long. It is therefore started at 57′20″ but not faded up until it is wanted as the closing link finishes. It runs for a further 1′10″ and brings the programme to an end on the hour

Preparing letters and cards

Presenters using letters from listeners will know that they are not always legible and cannot be used in the studio without some form of preparation. Some type out the basic information to ensure clarity, others prefer to work directly from the original cards and letters. It is important that names and addresses are legible so that the presenter is not constantly stumbling, or sounding as though the problem of deciphering a correspondent's handwriting is virtually insurmountable. In reality, this may often be the case, but a little preparation will avoid needlessly offending the people who have taken the trouble to write and on whom the programme depends. In this respect, particular care has to be taken over personal information such as names and ages, and it goes without saying that such things should be correctly pronounced. This also applies to streets, districts, hospitals, wards, schools and churches, where an incorrect pronunciation – even though it is caused by illegible handwriting – immediately labels the presenter as a ‘foreigner’ and so hinders listener identification. Such mispronunciations should be strenuously avoided, particularly for the community broadcasting station, and prior reference to telephone directories, maps and other local guides is essential.

Reading through the cards beforehand enables the presenter to spot dates, such as anniversaries, which will be past by the time of the broadcast. This can then be the subject of a suitable apology coupled with a message of goodwill, or alternatively the request can be omitted. What should not happen is for the presenter to realize on air during the introduction that the event which the writer anticipates has already happened. Not only does this sound unprofessional, but it gives the impression that the presenter does not really know what's happening, and worse, does not care. Anything that hinders the rapport between listener and presenter will detract from the programme.

In order to accommodate more requests and dedications, cards can be grouped together, sharing a single piece of music. The music need not necessarily be precisely what was asked for, providing that it is of a similar type to that requested – for example, by the same artist.

Such preparation of the spoken material makes an important contribution to the presenter's familiarity with the programme content. While it may be the intention to appear to be chatting informally ‘off the cuff’, matters such as pronunciation, accuracy of information, relevance of content, and timing need to be worked on in advance. The art is to do all this and still retain a fresh, ‘live’, ad lib sound. The experienced presenter knows that the best spontaneity contains an element of planning.

Programme technique

On the air, each presenter must find his or her own style and be true to it. No one person or programme will appeal to everyone but a loyal following can be built up through maintaining a consistent approach. A number of general techniques are worth mentioning.

Never talk over vocals. Given adequate preparation, it is often pleasing to make an accurate talk-over of the non-vocal introduction to a record. But talking over the singer's voice can be muddling, and to the listener may sound little different from interference from another station.

Avoid implied criticism of the listener's choice of music. The tracks may not coincide with your taste but they represent the broadcaster's intention to encourage public involvement. If a request is unsuitable, it is best left out.

Do not play less than one minute of anyone's request, or the sender will feel cheated. If the programme timing goes adrift it is generally better to drop a whole item than to compress. If the last item or the closing signature tune, or both, are ‘prefaded to time’ the programme duration will look after itself.

If, by grouping requests together, there are several names and addresses for a single record, prevent the information from sounding like a roll call. Break up the list and intersperse the names with other remarks.

Develop the habit of talking alternately to the general listener and to the individual listener who asked for the record. For example:

‘Now here's a card from someone about to celebrate 50 years of married bliss – that's what it says here and she's Mrs Jane Smith of Highfield Road, Mapperley. Congratulations Mrs Smith on your half century, you'd like to dedicate this record with all your love to your husband John. An example to the rest of us – congratulations to you too, John. The music is from one of the most successful shows of the sixties …’

Avoid remarks which, combined with the address, may pose any kind of risk to the individual.

‘… I'm asked not to play it before six o'clock because there's nobody at home till then …’

‘… she says she's living on her own but doesn't hear too well …’

‘… please play the record before Sunday the 18th because we'll all be away on holiday after that …’

‘… he says his favourite hobby is collecting rare stamps.’

Figure 13.3 Six ways of going from one music item to the next, with or without a speech link. The use of several different methods helps to maintain programme variety and interest

To reduce such risks, it is best to omit the house detail, referring only to the street and town. However, house numbers can generally be discovered by reference to voters’ lists and other directories. Broadcasters must always be aware of the possible illegal use of personal information.

It is often a wise precaution to keep the cards and letters used in a programme for at least a week afterwards in order to deal with music enquiries or other follow-up that may be required.

Guest programmes

Here, the regular presenter invites a well-known celebrity to the programme and plays his or her choice of music. The attraction of hearing artists and performers talk about music is obvious, but it is also of considerable interest to have the lives of others, such as politicians, sportsmen and women, and writers, illuminated in this way.

The production decisions generally centre on the ratio of music to speech. Is the programme really an excuse for playing a wide range of records or primarily a discussion with the guest but with musical punctuation? Certainly, it is easy to irritate the listener by breaking off an interesting conversation for no better purpose than to have a musical interlude, but equally a tiny fragment only of a Beethoven symphony can be very unsatisfying. The presenter, through a combination of interview style and links into and out of the music, must ensure an overall cohesiveness to prevent the programme sounding ‘bitty’. While it may be necessary to arrive at a roughly half and half formula, the answer could be to concentrate on the music where the guest has a real musical interest but to increase the speech content where this is not the case, using fewer but perhaps slightly longer music inserts.

Once again, the resolution of such questions lies in the early identification of a programme aim appropriate to the target audience.

DJ programmes

The radio disc jockey defies detailed categorization. His or her task is to be unique, to find and establish a distinctive formula different from all other DJs. The music content may vary little between two competing programmes and in order to create a preference the attraction must lie in the way it is presented. To be successful, therefore, the DJ's personality and programme style must not only make contact with the individual listener, but in themselves be the essential reason for the listener's attention. The style may be elegant or earthy, raucous or restrained, but for any one presenter it should be consistent and the operational technique first class.

The same rules of item selection and order apply as those already identified. The music should be sufficiently varied and balanced within its own terms of reference to maintain interest and form an attractive whole. Even a tightly formatted programme, such as a Top 40 show, will yield in all sorts of ways to imaginative treatment. One of the secrets is to be absolutely certain of the target audience. Top 40 for the 20–30 age group is radically different from Adult Contemporary for 25- to 40-year-olds. Different again is Nostalgia for the 40+ age group. The personal approach to this type of broadcasting differs widely and can be looked at under three broad headings.

The low-profile DJ

Here the music is paramount and the presenter has little to say – the job is to be unobtrusive. The purpose of the programme may be to provide background listening and all that is required is the occasional station identification or time check. In the case of a classical music programme, the speech/music ratio should obviously be low. The listener is easily irritated by a presenter who tries to take over the show from Berlioz and Bach. The low-profile DJ has to be just as careful over what is said.

The specialist DJ

Experts in their own field of music can make excellent presenters. They spice their introduction with anecdotes about the artists and stories of happenings at recording sessions, as well as informed comment on performance comparisons and the music itself. Jazz, rock, opera and folk all lend themselves to this treatment. Often analytical in approach, the DJ's job is to bring alive the human interest inherent in all music. The listener should obviously enjoy the tracks, but half the value of the programme is derived from hearing authoritative, possibly provocative, comment from someone who knows the field well.

The personality DJ

This is the most common of all DJ types. The role means doing more than just playing tracks with some spontaneous ad libs in between. However popular the music, this simple form of presentation soon palls. The DJ must communicate personally, creating a sense of friendship with the audience. Therefore, never embarrass the listener, either through incompetence or bad taste – the job is to entertain. To do this well, programme after programme, requires two kinds of preparation.

The first is in deciding what to say and when. This means listening to the music beforehand to decide the appropriate places for a response to the words of a song, a jokey remark or other comment, where to place a listener's letter, quiz question or phone call. The chat between records should be thought about in advance so that it doesn't sound pedestrian, becoming simply a repetitive patter. All broadcast talk needs some real substance containing interest and variety. This is not to rule out entirely the advantages of spontaneity and the ‘fly by the seat of your pants’ approach. The self-operating DJ, with or without a producer, is often capable of creating an entertaining programme, making it up as they go along. Undoubtedly, though, such a broadcaster is even better given some preparation time.

The programme may also contain identifications, weather and traffic information, commercials, time checks, trails for other programmes, and news. It may contain so many speech items that it is better described as a sequence rather than a DJ show, and this is developed further in the next chapter. But no presenter should ever be at a loss as to what to do next. The prerequisites are to know in advance what you want to say and be constantly replenishing your stock of anecdotes. Where possible, these should be drawn from your own observation of the daily scene. Certainly, for the local radio DJ, the more you can develop a rapport with the area, the more listeners will identify with you. The preparation of the programme's speech content will also include the timing of accurate talk-overs.

When a DJ is criticized for talking too much, what is often meant is that they are not interesting enough, i.e. there are too many words for little content. It is possible to correct this by talking less, but similarly the criticism will disappear if the same amount of speech is used to carry less waffle and more substance. Much of what is said may be trivial, but it should still be significant for the listener through its relevance and point of connection. So talk about things to which the listener can relate. Develop that rapport by asking – what information, what entertainment, what companionship does my listener need? If you don't know, go and meet some of them. And remember that there is a key factor in establishing your credibility – it's called professional honesty.

The second kind of preparation for a DJ, and where appropriate the producer, is in actually making additional bits and pieces of programme material which will help to bring the show alive. Probably recorded, these may consist of snatches of conversation, sound effects, funny voices on echo, stings, chords of music and so on. Presenters may even create extra ‘people’, playing the roles themselves on the air, talking ‘live’ to their own recording. Such characters and voices can develop their own personalities, appearing in successive programmes to become very much part of the show. Only the amount of time which is set aside for preparation and the DJ's own imagination sets limits on what can be achieved in this way.

For the most part, such inserts are very brief but they enliven a DJ's normal speech material, adding an element of unpredictability and increasing the programme's entertainment value.

Whether the programme is complex or simple, the personality DJ should, above all, be fun to listen to. But while the show may give the impression of a spontaneous happening, sustained success is seldom a matter of chance. It is more likely to be found in a carefully devised formula and a good deal of preparation and hard work.