23

Programme evaluation

A crucial activity for any producer is the regular evaluation of what he or she is doing. Programmes have to be justified. Other people may want the resources or the airtime. Station owners, advertisers, sponsors and accountants will want to know what programmes cost and whether they are worth it. Above all, conscientious producers striving for better and more effective communication will want to know how to improve their work and achieve greater results. Broadcasters talk a great deal about quality and excellence, and rightly so, but these are more than abstract concepts, they are founded on the down-to-earth practicalities of continuous evaluation.

Programmes can be assessed from several viewpoints. We shall concentrate on three:

![]() Production and quality evaluation

Production and quality evaluation

![]() Audience evaluation

Audience evaluation

![]() Cost evaluation.

Cost evaluation.

Production evaluation

Programme evaluation carried out among professionals is the first of the evaluative methods and should be applied automatically to all parts of the output. However, it is more than simply a discussion of individual opinion, for a programme should always be evaluated against previously agreed criteria.

First, the basic essential of the proper technical and operational standard. This means there is no audible distortion, that intelligibility is total, that the sound quality, balance and levels are correct, the fades properly done, the pauses just right and the edits unnoticeable.

Second, what is the programme for – what does it set out to do? A statement of purpose should be formulated for every programme so that it has a specific direction and aim. Without such an aim, any programme can be held to be successful. So, what is the ‘target audience’? What is the programme intending to do for that audience? How well does it set about doing it? (Whether it actually succeeds in this is an issue for audience evaluation.)

Third, a professional evaluation of content and format. Were the interviews up to standard? The items in the best order? The script lucid and the presenter communicative? These questions are best discussed at a regular meeting of producers run by the senior editorial figure. It is important at these meetings that everyone has heard the programme under review – either off-air or played at the start of the meeting. It is good to have some positive feedback first. What did we like about it? In what ways did we feel it appealed to the target audience? What could be improved? Is there a follow-up? Everyone should be encouraged to take part in this evaluation, including of course the programme's producer. The focus of the discussion should be on constructive improvement rather than finding fault. When producers are first involved in playback and discussion sessions, they are bound to show some initial defensiveness and sensitivity over their work. This has to be understood. It is best minimized by focusing the discussion on the programme, not on the programme maker. The process is essentially about problem solving and creatively seeking new ideas in pursuit of the programme aim.

Programme quality

Quality is a much overused word in programme making. Is it only something about which people say ‘I know it when I see it or hear it, but I wouldn't like to say what it is’? If so, it must be difficult to justify the judges’ decisions at an awards ceremony. Of course, there will be a subjective element – a programme will appeal to an individual when it causes a personal resonance because of experience, preference or expectation. But there must also be some agreed professional criteria for the evaluation of programme excellence – quality will mean that at least some of the following eight components will be in evidence.

First, appropriateness. Irrespective of the size of the audience gained, did the programme actually meet the needs of those for whom it was intended? Was it a well-crafted piece of communication which was totally appropriate to its target listeners, having regard to their educational, social or cultural background? Programme quality here is not about being lavish or expensive, it is about being in touch with a particular audience, in order exactly to serve it, providing with precision the requirements of the listener.

Second, creativity. Did the programme contain those sparks of newness, difference and originality that are genuinely creative, so that it combined the science and logic of communication with the art of delight and surprise? This leaves a more lasting impression, differentiating the memorable from the dull, bland or predictable.

Third, accuracy. Was it truthful and honest, not only in the facts it presented and in their portrayal and balance within the programme, but also in the sense of being fair to people with different views? It is in this way that programmes are seen as being authoritative and reliable – essential of course for news, but necessary also for documentary programmes, magazines and, in its own way, for drama.

Fourth, eminence. Quality acknowledges known standards of ability in other walks of life. A quality programme is likely to include first-rate performers – actors or musicians. It will make use of the best writers and involve people eminent in their own sphere. This, of course, extends to senior politicians, industrial leaders, scientists, sportsmen and women – known achievers of all kinds. Their presence gives authority and stature to the programme. It is true that the unknown can also produce marvels of performance, but quality output cannot rely on this and will recognize established talent and professional ability.

Fifth, holistic. A programme of quality will certainly communicate intellectually in that it is understandable to the sense of reason, but it should appeal to other senses as well – the pictorial, imaginative or nostalgic. It will arouse emotions at a deeper and richer level, touching us as human beings responsive to feelings of awe, love, compassion, sadness, excitement – or even the anger of injustice. A quality programme makes contact with more of the whole person – it will surely move me.

Sixth, technical advance. An aspect of quality lies in its technical innovation, its daring – either in the production methods or the way in which the audience is involved. Technically ambitious programmes, especially when ‘live’, still have a special impact for the audience.

Seventh, personal enhancement. Was the overall effect of the programme to enrich the experience of the listener, to add to it in some way rather than to leave it untouched – or worse to degrade or diminish it? The end result may have been to give pleasure, to increase knowledge, to provoke or to challenge. An idea of ‘desirable quality’ should have some effect which gives, or at least lends, a desirable quality to its recipient. It will have a ‘Wow’ factor.

Eighth, personal rapport. As the result of a quality experience, or perhaps during it, the listener will feel a sense of rapport – of closeness – with the programme makers. One intuitively appreciates a programme that is perceived as well researched, pays attention to detail, achieves diversity or depth, or has personal impact – in short, is distinctive. The listener identifies not only with the programme and its people, but also with the station. Programmes which take the trouble to reach out to the audience earn a reciprocal benefit of loyalty and sense of ownership.

Combining accuracy with appropriateness, for example, means providing truthful and relevant news in a manner that is totally understandable to the intended audience at the desired time and for the right duration. Quality news will also introduce creative ways of fairly describing difficult issues, so leaving the listener feeling enriched in his or her understanding of the world.

Programme quality requires several talents. It takes time to think through and is less likely to blossom if the station's primary requirement is quantity rather than excellence. It cannot be demanded in every programme, for creativity requires experiment and development. It needs the freedom to take risks and therefore occasionally to make mistakes. Qualitative aspects of production are not easy to measure, and it may be that this is why an experienced programme maker determines them intuitively rather than by logic alone. Nevertheless, they have to be present in any station that has quality on the agenda or aspires to be a leading broadcaster.

Quality allied to programming as a whole – especially that thought of as public service – takes us back to criteria described on p. 12. Quality in this sense will mean a diversity of output, meeting a whole range of needs within the population served. It will reflect widely differing views and activities, with the intention of creating a greater understanding between different sections of the community. Its aim is to promote tolerance in society by bringing people together – surely always the hallmark of quality communication.

The cynic will say that this is too idealistic and that broadcasting is for self-serving commercial or even propagandist ends – to earn a living and provide music to ease the strain of life for listeners. If this is the case, then simply evaluate the activity by these criteria. The many motivations for making programmes and the values implicit in the work are outlined on p. 16. What is not in doubt is the need to evaluate the results of what we do against our reason for doing it.

Audience evaluation

Formal audience research is designed to tell the broadcaster specific facts about the audience size and reaction to a particular station or to individual programmes. The measurement of audiences and the discovery of who is listening at what times and to which stations is of great interest not only to programme makers and station managers, but also to advertisers or sponsors who buy time on different stations. Audience measurement is the most common form of audience research, largely because of the importance attached to obtaining this information by the commercial world.

Several methods of measurement are used and, in each, people are selected at random from a specific category to represent the target population:

1 People are interviewed face to face, generally at home.

2 Interviews are conducted by phone.

3 Respondents complete a listening diary.

4 A selected sample wear a small personal meter.

The more detailed the information required – the number of people who heard part or all of a given programme on a particular day, and what they thought of it – the more research will cost. This is because the sample will need to be larger, requiring more interviews (or more diaries) and because the research has to be done exclusively for radio. If the information required is fairly basic – how many people tuned to Radio 1 for any programme last month and their overall opinion of the station – the cost will be much less, since suitable short questions can be included in a general market survey of a range of other products and services.

It should be said that constructing a properly representative sample of interviewees is a process requiring some precision and care. For example, we know that the unemployed are likely to be heavy users of the media generally, yet as a category they are especially difficult to represent. Nevertheless, a correct sample should cover all demographic groups and categories in terms of age, gender, social or occupational status, ethnic culture, language and lifestyle, e.g. urban and rural. It should reflect in the proper proportions any marked regional or other differences in the area surveyed. This pre-survey work ensures, for example, that the views of Hindi-speaking students, male and female, are sought in the same ratio to the over-65s living in rural areas as these two categories exist in the population as a whole. Only when the questioning is put to a correctly constructed sample of the potential audience will the answers make real sense.

A further important definition relates to the meaning of the word ‘listener’. Many sequence programmes are two or three hours long – do we mean a listener is someone who listened to it all? If not, to how much? In Britain, RAJAR – Radio Joint Audience Research – conducts surveys of all radio listening using a self-completion diary. Here a listener is defined as someone who listens for a minimum of five minutes within a 15-minute time segment. The figure for weekly reach is the total number of such listeners over a typical week, expressed as a percentage of the population surveyed. The resulting figures have even more value over a period of time, as they indicate trends in programme listening, seasonal patterns and changes in a specific audience, such as car drivers. This allows comparisons to be made between different kinds of format and schedule. Research therefore helps us to make programme decisions, as well as providing the figures for managers to justify the cost of airtime.

Personal meters

Many methods of radio audience measurement depend on listeners’ memories and on whether they actually know what radio stations they have been listening to. There are electronic methods that get round these problems. For example, a selected number of people agree to wear a small personal programme meter that records what stations the wearer has been in the audible presence of during his or her waking hours. This might be a small pager-sized meter that relies on all radio and TV stations having an embedded but inaudible identity code that it can recognize and record. Another system involves wearing a watch that records and compresses four seconds of sound during every minute that the watch is worn. These compressed digital clips are then compared with all output of all radio and TV stations during the period being measured. At the end of a period – daily or weekly – the data contained in the device is sent to a computer via a telephone line for analysis. Such systems are in regular use and can be expected to grow over the next few years. One major advantage is that they provide comparable data for both radio and TV from the same source. The main disadvantage is the higher cost involved. A major question for researchers, station directors and advertisers is whether a radio station that is merely heard, perhaps unintentionally, is the same thing as one that is deliberately tuned to.

Research panels

Another method of research is through listening panels scattered throughout the coverage area. Such groups can, by means of a questionnaire, be asked to provide qualitative feedback on programmes. Panel members will be in touch with their own community and therefore may be chosen to be broadly representative of local opinion. Once a panel has been established, its members can be asked to respond to a range of programme enquiries, which over time may usefully indicate changes in listening patterns.

Such panels are also appropriate where the programme is designed for a specific minority, such as farmers, the under-fives, the unemployed, hospital patients, adult learners, or a particular ethnic or language group. Here, the panel may meet together to discuss a programme and provide a group response. Visited by programme makers from time to time, a panel can sustain its interest by undertaking responsible research for the station. But beware any such sounding-board which is too much on the producer's side. Too close an affiliation creates a desire to please, whereas programme makers must hear bad news as well as good. Indeed, one of the key survey questions is always to find out why someone did not listen to my programme.

Questionnaires

In designing a research questionnaire ensure that the concepts, words and format are appropriate to the person who will be asked to complete it. A trained researcher filling in the form while undertaking an interview can cover greater complications and variables than a form to be completed by an individual listener on their own. Before large-scale use, any draft questionnaire should be tested with a pilot group to reveal ambiguities or misunderstandings. Here are some design criteria:

![]() Decide exactly what information you need, and how you will use it.

Decide exactly what information you need, and how you will use it.

![]() Do not ask for information you don't need – redundant questions only complicate things.

Do not ask for information you don't need – redundant questions only complicate things.

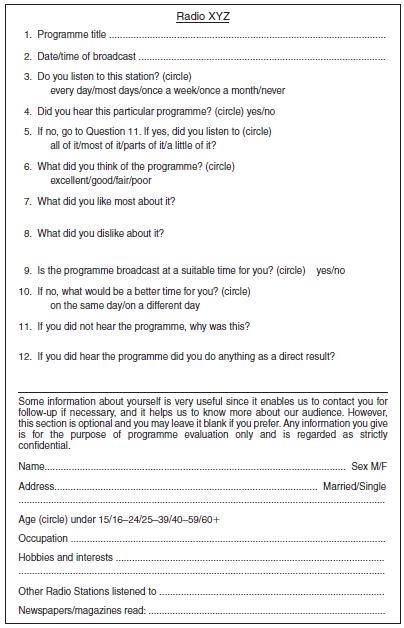

Figure 23.1 A simple audience research questionnaire for individual members of a listening panel. The station completes 1 and 2 before distribution

![]() Write the introduction to indicate who wants the information, and why, and what will be done with it. Establish the level of confidentiality.

Write the introduction to indicate who wants the information, and why, and what will be done with it. Establish the level of confidentiality.

![]() Number each question for reference.

Number each question for reference.

![]() The layout should be in lines rather than boxes or columns. This enables it to be completed either by typing or longhand.

The layout should be in lines rather than boxes or columns. This enables it to be completed either by typing or longhand.

![]() The information you may want is in three categories:

The information you may want is in three categories:

– Facts: name, age, family, address, job, newspapers read.

– Experience: listening habits, reception difficulties, use of TV/videos.

– Opinion: views of programmes, presenters, of competitor stations.

![]() Questions here come in four categories:

Questions here come in four categories:

– Where the answer is either yes or no: Are you able to receive Radio XYZ? Yes/No

– Where you offer a multiple-choice question: How difficult is it to tune your radio to Radio XYZ? Very difficult/Moderately difficult/ Fairly easy/Very easy

– Where you provide a numerical scale for possible answers: On a scale of 0–5, how difficult is it to tune your radio to Radio XYZ? Very difficult 0 … 1 … 2 … 3 … 4 … 5 Very easy

– Where you invite a reply in prose: What difficulties have you had in receiving Radio XYZ?

![]() Yes/No, tick box, multiple-choice and numerical scale questions take up little space and can be given number values, and so are useful in producing statistics.

Yes/No, tick box, multiple-choice and numerical scale questions take up little space and can be given number values, and so are useful in producing statistics.

![]() Add ‘other’ to appropriate multiple-choice questions to allow for responses you have not thought of.

Add ‘other’ to appropriate multiple-choice questions to allow for responses you have not thought of.

![]() Prose answers can be difficult to decipher but give good insights and usable quotes.

Prose answers can be difficult to decipher but give good insights and usable quotes.

![]() Avoid imprecise terms – ‘often’, ‘generally’, ‘useful’ – other than in a multiple-choice sequence.

Avoid imprecise terms – ‘often’, ‘generally’, ‘useful’ – other than in a multiple-choice sequence.

![]() Avoid questions that appear to have a right or preferred answer.

Avoid questions that appear to have a right or preferred answer.

![]() Keep the questionnaire simple and as short as possible.

Keep the questionnaire simple and as short as possible.

Needless to say, the whole area of audience research is too big to be dealt with fully here. Further sources of information are listed under Further reading.

Letter response

Informal audience research – anecdotal evidence, press comment and immediate feedback – often has an impact on the producer that is out of proportion to its true value. Probably the most misleading of these – in relation to the listenership as a whole – is the letter response. Several studies have shown that there is no direct correlation between the number of letters received and the size or nature of the audience. News is often the most listened-to part of the output, yet the newsroom receives comparatively few letters.

Letters will indicate something about the individuals who are motivated to write – where they live, their interests perhaps, what triggered them to pick up a pen, or what they want in return. But it is wrong to think that each writer represents a thousand others – they may do, but you don't know that and cannot assume it. There may be more letters from women than from men – does that indicate that there are more women listeners than men? Not necessarily – it may be that women have more time, are more literate, are more motivated, or have the stamps!

Broadcasting to ‘closed’ countries, or where mail is subject to interference, frequently results in a lack of response, which by no means necessarily indicates a small audience. Low literacy or a genuine inability to pay the postage are other factors which complicate any real accuracy in attempting audience evaluation through the correspondence received. It may give some useful indicators and raise questions worthy of feeding back into programmes – for each individual letter has to be taken most seriously – but letter writers are self-selecting along patterns which are likely to have more to do with education, income, available time and personal motivation than with any sense of the audience as a whole.

A method which partly overcomes the unknown and random nature of letter response is to send with every reply to a correspondent a questionnaire (together with a stamped addressed return envelope) designed to ask about the writer's listening habits, to your own and to other services. It also asks for information about the person. Over a period of several months it is possible to build up some useful demographic data. It still only relates to those who write, but it can be compared with official statistical data – available from many public libraries – to discover how representative are the people who write.

Cost evaluation

What does a programme cost? Like many simple questions in broadcasting this one has a myriad possible answers, depending on what you mean.

The simplest answer is to say that a programme has a financial budget of ‘X’ – an amount to cover the ‘above the line’ expenses of travel, contributors’ fees, copyright, technical facilities and so on. But then what is its cost in ‘people time’? Are staff salaries involved – producer, technical staff, secretarial time? Or office overheads – telephone, postage, etc.? Is the programme cost to include studio time, and is that costed by the hour to include its maintenance and depreciation? And what about transmission costs – power bills, engineering effort, capital depreciation?

Total costing will include all the management costs and all the overheads, over which the individual programme maker can have little or no control. One way of looking at this is to take a station's annual expenditure and divide it by the number of hours it produces, so arriving at a cost per hour. But since this results in the same figure for all programmes, no comparisons can be made. More helpful is to allocate to programmes all cash resource costs which are directly attributable to it, and then add a share of the general overheads – including both management and transmission costs – in order to arrive at a true, or at least a truer, cost per hour figure which will bear comparison with other programmes.

Does news cost more than sport? How expensive is a well-researched documentary or a piece of drama? How does a general magazine compare with a phone-in or a music programme? How much does a ‘live’ concert really cost? Of course, it is not simply the actual cost of a programme which matters – coverage of a live event may result in several hours of output, which with recorded repeat capability could provide a low cost per hour. Furthermore, given information about the size of the audience it is possible, by dividing the cost per hour by the number of listeners, to arrive at a cost per listener hour. So is this the all-important figure? No, it is an indicator among several by which a programme is evaluated.

Relatively cheap programmes which attract a substantial audience may or may not be what a station wants to produce. It may also want to provide programmes that are more costly to make and designed for a minority audience – programmes for the disabled, for a particular linguistic, religious or cultural group, or for a specific educational purpose. These will have a higher cost per listener hour, but will also give a channel its public service credibility. It is important for each programme to be true to its purpose – to achieve results in those areas for which it is designed. It is also important for each programme to contribute to the station's purpose – its Mission Statement.

After a full evaluation, happy is the producer who is able to say ‘My programme is professionally made to a high technical standard, it meets precisely the needs of the whole audience for which it is intended, its cost per listener hour is within acceptable limits for this format, and it contributes substantially to the declared purpose of this station.’ Happy, too, is the station manager.