Chapter 7

Levi ben Gershon and the Jacob’s Staff

1325 CE

There are two different methods for finding one’s way at sea. One way is to hug coastlines, watching for familiar landmarks like mountains or islands or towns and then steering the ship toward them. This method works pretty well as long as you have familiar landmarks and a map that shows them.

But what do you do when you are far out on the open ocean with only stars and the sun for guides? That’s the time when you employ celestial navigation, the technique of using the positions of stars, the moon, and the sun in the sky to find your current position. One of the earliest instruments for celestial navigation was the Jacob’s staff.

The Rabbi Finds His Way

In the days before global positioning systems, satellites, and computers, how did sailors like Christopher Columbus navigate from one port to another? Well, there were several methods.

Dead reckoning was a popular one. The captain would trail a floating line of a known length from the back of his ship and record the time it took to pay out completely. He then knew roughly how fast the ship was traveling, and using this information combined with a compass, he could estimate his ship’s change in position from one day to another.

In theory, this was a pretty straightforward process. Say it took a sailor 6 minutes (or 1⁄10th of an hour) to unreel a line that was 1,056 feet (1⁄5th of a mile) long. That meant the ship was sailing .2 mile/.1 hour, or 2 miles an hour.

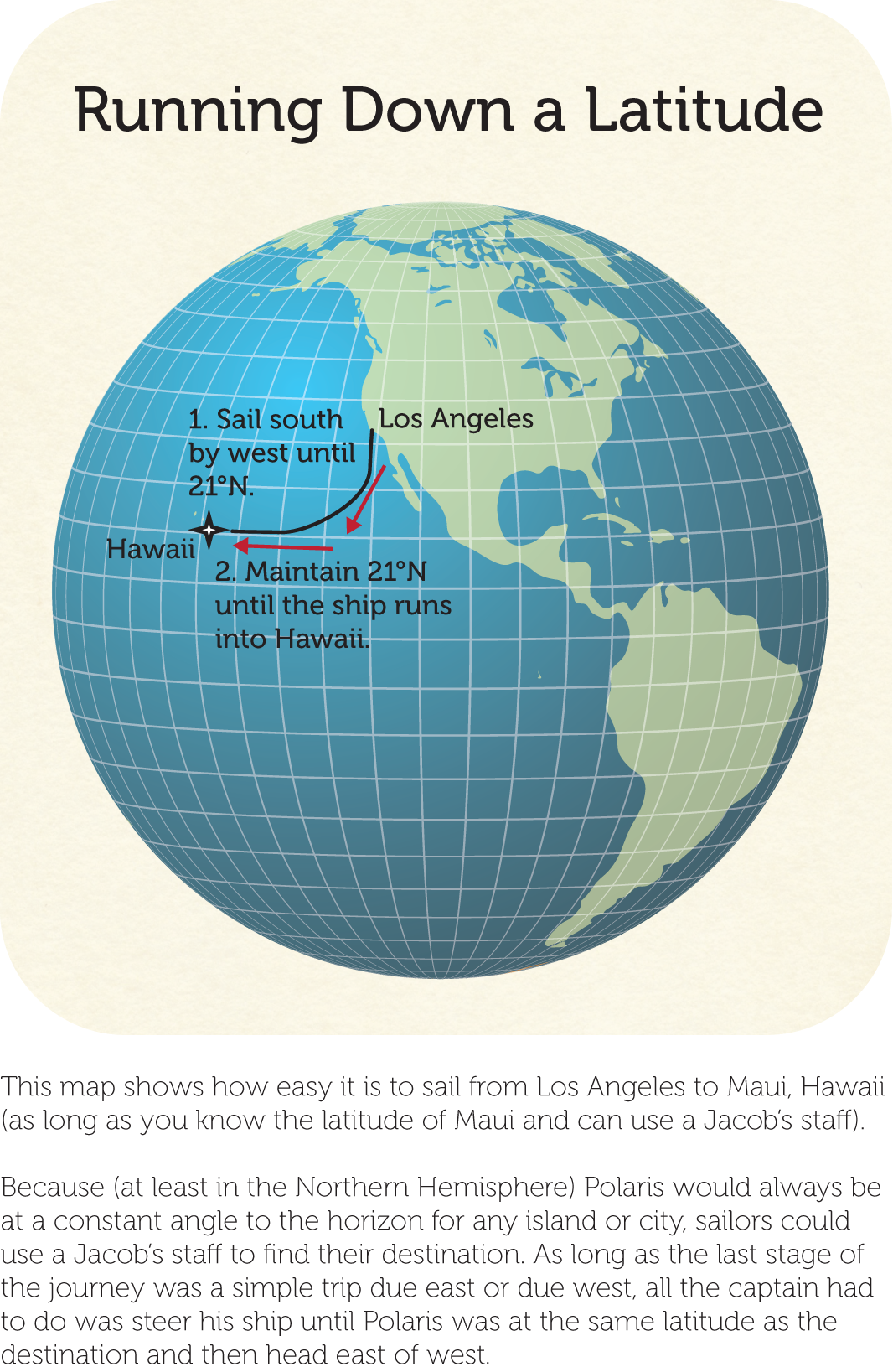

But in practice this method wasn’t a very accurate way of knowing where you were. Small errors really added up over long distances, and changing wind and weather added a lot of inaccuracy. So instead, Medieval- and Renaissance-era navigators used a somewhat more accurate technique called “running down a latitude.” This meant the captain would take the ship to whatever latitude the desired port was on and then he would steer due east or west until he more or less ran into it (see Figure 7-1).

This simple method required an instrument that would allow the navigator to accurately determine and track a ship’s current latitude. The first really scientific navigational instrument that could do this was invented by a now little-known, but immensely gifted, 14th century French mathematician and rabbi named Levi ben Gershon. In addition to the invention of the Jacob’s staff, Rabbi Gershon was responsible for a number of important mathematical advances in the fields of geometry, trigonometry, logic, and mathematical education.

Gershon wrote many books, all of them in Hebrew. He was highly respected, not only within the Jewish community, but among all the learned men of his day. In fact, while he was alive, Christian scholars translated several of his books and published them in Latin. This is noteworthy, given the significant amount of work involved in pre-Gutenberg book publishing.

But Rabbi Gershon was more than a theoretician. He applied his mathematical discoveries to real-world problems. The most notable example of this is the Jacob’s staff.

Also called a cross-staff, Gershon’s invention was a navigational instrument that had a pair of sliding sights and a horizontal bar that bore a carefully incised geometric scale. By measuring the arc between the measured object and the horizon with the cross-staff, the navigator could accurately determine angles and, therefore, latitude. This allowed ships to run down a latitude and safely reach their intended port (see Figure 7-1).

Figure 7-1: Running down a latitude

For 200 years, ship captains used Jacob’s staffs to find their way at sea. There was nothing better and more reliable until the more sophisticated backstaff was invented in 1590 by English sea captain John Davis.

Laying Out a Jacob’s Staff

Making your own Jacob’s staff is easy if you are precise about cutting wood to length and are careful about layout lines. Make sure both your saw and pencil points are sharp!

Assembling the Jacob’s Staff

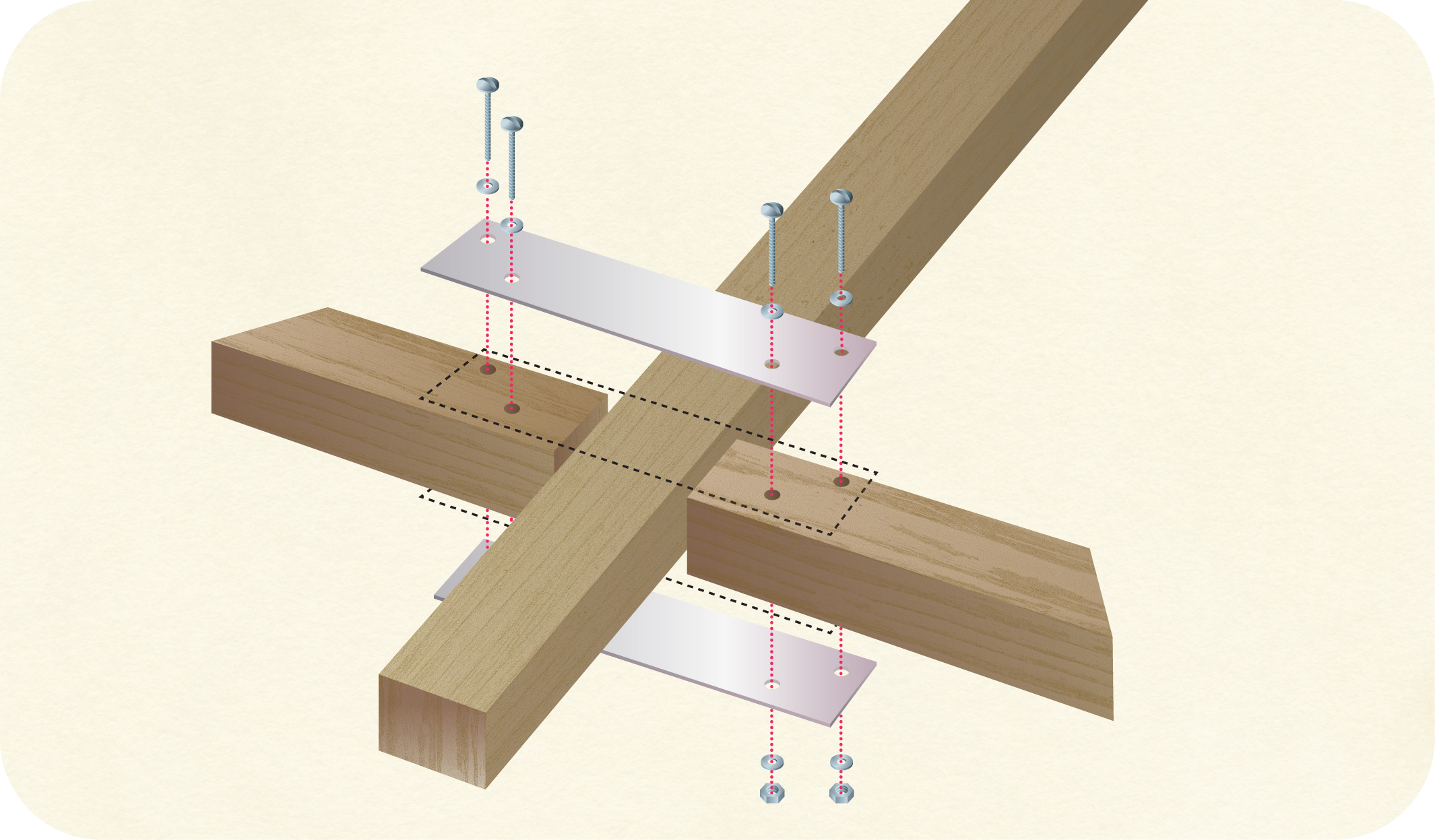

Before you begin, take a look at the assembly diagram in Figure 7-2.

After you’ve seen what you’re shooting for, follow these steps:

- Saw a 45-degree angle onto one end of each 4½-inch dowel.

- Position the short dowels on either side of the long dowel.

- Place and center the brass strip over the short dowels and then attach it by drilling a 3⁄16-inch hole and fastening it to the dowels with the machine screws, washers, and nuts. (Refer to the assembly drawing in Figure 7-2.) The short-dowel/brass-strip assembly should slide easily along the length of the 36-inch dowel.

Figure 7-2: Assembling the Jacob’s staff

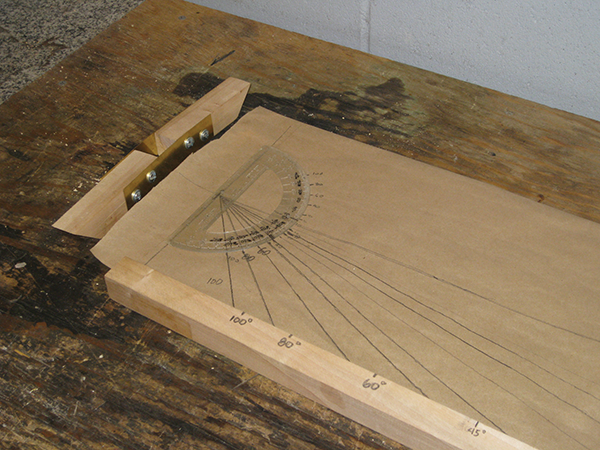

Now that you’ve constructed the staff, it’s time to add the scale that allows you to read latitude. Refer to Figure 7-3 for the remaining steps.

- Now draw a vertical line 2 inches from one of the shorter edges of your piece of paper.

- Next, draw a horizontal line down the center of the long dimension of the paper.

- Align your protractor’s bottom edge with the vertical line and place the protractor’s center point at the intersection of the two lines. Note that the paper is exactly the same width as the length of the short-dowel/brass-strip assembly.

Figure 7-3: Marking the latitude scale

- With a pencil, draw 100°, 80°, 60°, 45°, 40°, 30°, 20°, and 10° lines, radiating from the protractor’s center point to the paper’s bottom edge as shown in Figure 7-3.

- Place the 36-inch dowel next to the paper and align one edge of the dowel with the vertical line.

- Mark the dowel with the corresponding degrees where the lines intersect the paper’s edge.

Congratulations! Your Jacob’s staff is complete (see Figure 7-4) and you are ready to navigate!

Figure 7-4: The assembled Jacob’s staff

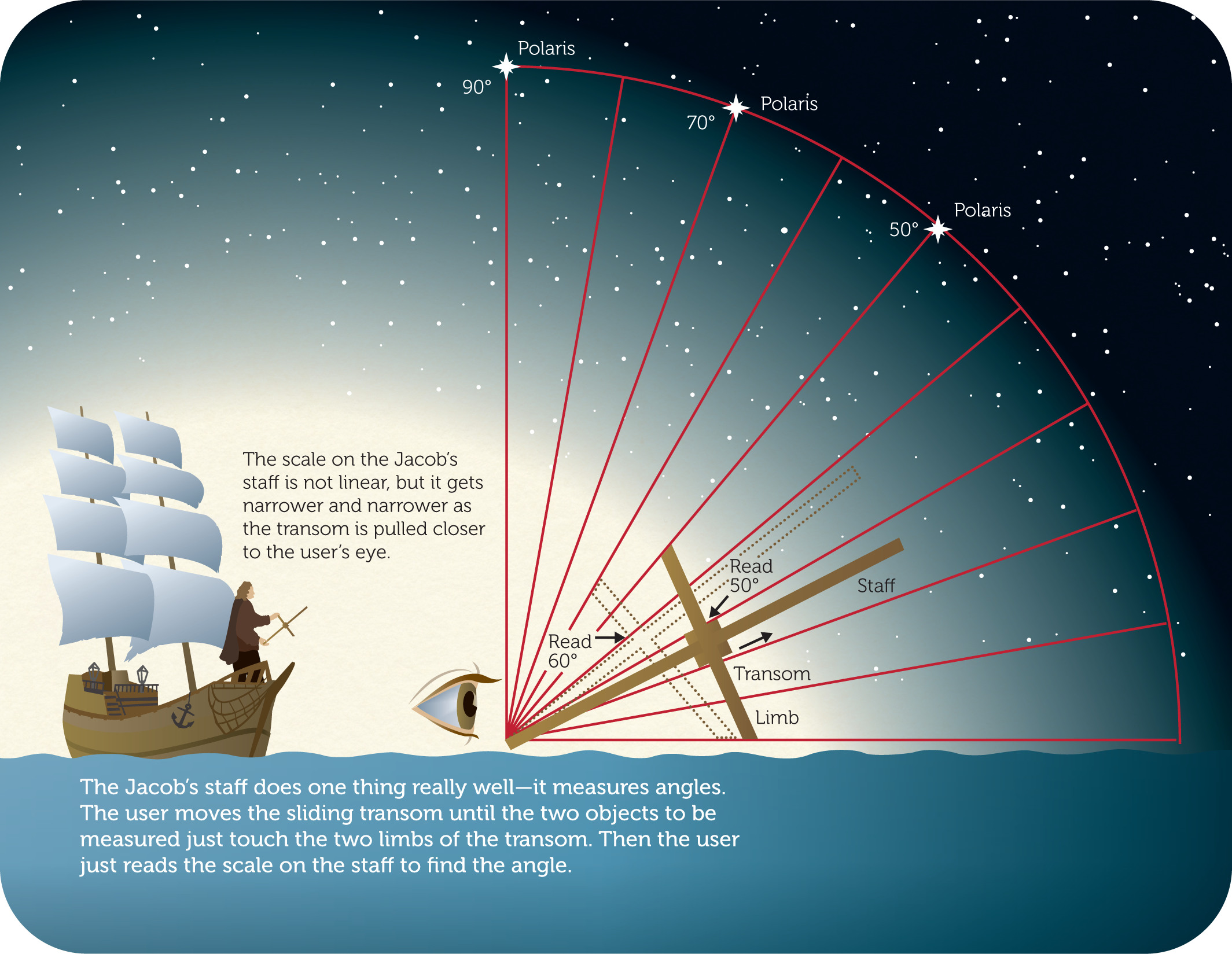

Go West (or East) Young Man

Now that you’ve assembled your staff, it’s time to try it out. After dark, go outside with your staff and slide the short-dowel/brass-strip assembly until the edge of top dowel aligns with Polaris (the North Star) and the edge of the bottom dowel aligns with the horizon. Once you’ve positioned your dowels, you can read your current latitude from the scale you marked on the long dowel. If you have done a careful job of drawing the scale, you can figure out your latitude with reasonably good accuracy. Take a look at Figure 7-5 for a more detailed explanation of what’s going on.

Figure 7-5: Using the Jacob’s staff

If you can maintain a constant reading on the Jacob’s staff as you travel, you are staying on the same line of latitude. But if you veer south, Polaris appears to sink in the sky as you sight it through your device. If you travel north, Polaris seems to rise.

Experienced navigators can also use the Jacob’s staff with the noon sun to determine their latitude during the day (assuming it’s a clear day). This requires a darkened lens that allows the navigator to safely stare at the sun, as well as a special astronomical table called an ephemeris that provides data on where the sun is in the sky at noon on any given day.