Change is certain … such recurrences should not constitute occasions for sadness but realities for awareness ...

Nothing is so painful to the human mind as a great and sudden change.

You might think these contrasting views on change must have been expressed by two people of different cultures living far apart; but in fact, they were married to each other. The first phrase was penned by English poet Percy Shelley during his short lifetime from 1792 to 1822, and the second phrase comes from his wife Mary Shelley’s first edition of the novel Frankenstein published in 1818 (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Mary Shelley and Percy Shelley—Different views on change

Source: https://lithub.com/the-treacherous-start-to-mary-and-percy-shelleys-marriage/

Borrowing from medical terminology, Percy Shelley seems to be describing chronic or ongoing change while his wife, Mary, seems to be referring to acute or sudden change. Communities incur both types of change. One town could face continuous development pressures from a nearby larger city and another could suddenly lose a major employer. Change can, and should, also come from within—a desire for self-improvement. Whether change is fast or slow, severe or mild, or internal or external, there is much wisdom in Percy Shelley’s words that change should create “realities for awareness.” In the context of this book, it means that communities should be prepared to adapt and benefit from change.

From Change to New Normal

Acute and chronic can be useful terms for characterizing and understanding change; but sometimes, generational events such as the COVID-19 pandemic come roaring in so fast and hard that only words such as tsunami can describe them. The pandemic affected countries around the world and the communities within them. When a change of this magnitude occurs, the term “new normal” usually comes into play. New normal is a pretty serious phrase because it implies a significant change in our usual customs and routines. Dictionary.com defines new normal as “a current situation, social custom, etc., that is different from what has been experienced or done before but is expected to become usual or typical.” According to this definition, there are two aspects of a new normal: significance and longevity.

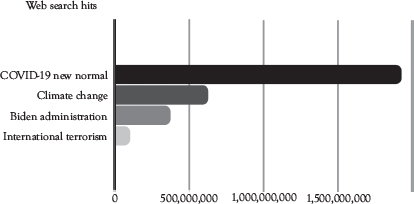

Internet searches for the phrase “COVID-19 new normal” (in Summer 2021) generated 1.93 billion results (Figure 1.2). If web search hits are any indication of the relative importance placed on events or issues by the public, then the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on how we live our daily life far outscores climate change (622 million hits), Biden Administration (371 million hits), and international terrorism (102 million hits).

Figure 1.2 Web Searches: COVID-19 New Normal vs. Others

New normal terminology is not unique to the COVID-19 pandemic. It has long been applied to a variety of situations. In 1918, new normal was used to describe the impact of World War I: “we must divide our epoch into three periods: that of war, that of transition and that of the new normal.”1 It has been used to describe the aftermath of a variety of financial disruptions including the 1990s dot-com bubble and the 2008 financial crisis and recession, and it has been applied to political transitions and new administrations. New Normal was even the title of a sitcom that aired on NBC from 2012 to 2013.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 is a recent example of a potentially long-term global political new normal. The invasion prompted a host of countries, including the United States and many European countries, to rethink their postwar foreign policies and impose economic sanctions on Russia to counter its military action. NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg stated that “It’s obvious that we are faced with a new reality, a new security environment, a new normal.2”

Realizing that the term new normal is not unique to the COVID-19 pandemic raises several questions. When the term new normal is used, is the change really just a temporary aberration or something that will have a longer-lasting impact and therefore meet both aspects of the previously mentioned definition? How significant are the social, economic, and other changes in the new normal? How widespread are its effects across geographic and socioeconomic lines? Do we create categories for classifying new normals the way we do for hurricanes?

Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic

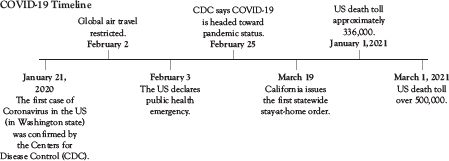

The social and economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic was swift and historically significant as shown in this partial timeline of U.S. events (Figure 1.3).

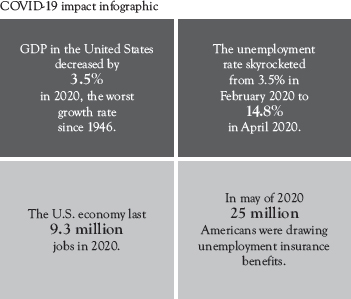

Figure 1.4 shows how quickly and deeply the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic hit the United States.3

A June 2020 survey by ProsperousPlaces.org of local community and economic development professionals found that on average 48 percent of retail/restaurant businesses and 17 percent of all other businesses including manufacturing firms were closed in the respondents’ communities as a result of the pandemic.4

Globally, the overall economic impact was equally significant. According to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, the global GDP growth rate for 2020 was negative 5.0 percent, and the UN predicts that it will take several years to return to prepandemic levels. The world economy is expected to lose 8.5 trillion dollars in output for the two-year period from 2021 to 2022, erasing almost all of the increase for the previous four years and representing the sharpest contraction since the Great Depression in the 1930s.5

Figure 1.4 COVID-19 economic impact in the United States

The COVID-19 downturn affected industries and regions in different ways and with varying degrees of severity. The travel industry experienced a 42 percent decline in revenue in 2020,6 but the online shopping industry thrived, with Amazon reporting a 37 percent increase in sales for 2020 over 2019.7 A study by the Brookings Institute compared the different impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on industries and cities that rely on the movement of people with those that rely on the movement of information.8 As the accompanying box shows, Las Vegas and Orlando, whose respective gaming and tourism economies rely more on the movement of people, were much harder hit by the pandemic than was Seattle with its software and information technology industries. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic had a disproportionate impact on minorities in many areas because of their higher employment concentrations in industries more affected by the downturn.

Some Cities and Workers Hit Harder by Pandemic

Las Vegas, Nevada’s, core industries of gaming, tourism, and conventions rely heavily on the movement of people in and out of the city and the pandemic hit it hard. In the twelve-month period between November 2019 and November 2020 which includes the onset of the COVID-19 virus in the United States in the spring of 2020, the unemployment rate in the Las Vegas-Henderson-Paradise metropolitan area increased from 3.6 to 11.5 percent.

In the Orlando-Kissimmee-Sanford, Florida metropolitan area, another region that relies heavily on tourism, the unemployment rate increased from 2.7 to 7.7 percent during that same 12-month period. As a benchmark, the unemployment rate for the United States as a whole increased from 3.3 to 6.1 percent during that time, and, as noted earlier, spiked in April 2020 to 14.8 percent, remaining in double digits through July 2020.

In Las Vegas and Orlando, the shares of employment accounted for by the leisure and hospitality sectors that rely on moving people are relatively high (28 and 21 percent, respectively); however, the shares of employment accounted for by the professional and business service sectors that rely more on moving and processing information in these cities are relatively low (15 and 18 percent, respectively). By contrast, in the Seattle, Washington metro area, more of an information and goods moving region known for software and aviation products, the unemployment rate increased by only 2.1 percentage points from 3 percent in November 2019 to 5.1 percent in November 2020.

According to the Brookings study, in Las Vegas, Hispanic or Latino workers account for almost 25 percent of employment in the leisure and hospitality sectors with more person-to–person contact and less than 15 percent in the financial and information sectors. COVID-19 cases per 1,000 residents in the Las Vegas metro area were therefore much higher among Hispanic or Latino residents than white residents. On an age-adjusted basis, the COVID-19 death rates at the state level in Nevada for Hispanic or Latino residents through January 2021 were three times greater than those for white residents. The Brookings study provides a framework for understanding the differential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on industries, cities, and ethnic groups. Such an analysis can help elected officials and policy makers at the national and local levels make more informed and equitable pandemic recovery decisions.

A Mega New Normal?

If new normal can be used to describe the aftermath of a sudden and distinct event such as a pandemic, financial crisis, or even war, then why can’t it also be applied to more gradual but equally significant events and trends—sometimes referred to as long-wave changes? The case can be made that technological innovations over the past few decades have created a “mega” new normal. Culture and Creativity offers an assessment of some highly significant but more gradual changes that have occurred in recent years in the new age of instant communications:

Terrorism, war, new technologies, rapid political take-offs and no less rapid falls—we saw pretty much the same things in the 1960s, the 1970s, the 1980s, and the 1990s. Significant changes able to shape a nation or change a society happened in long waves encompassing entire generations and not just decades. Indeed, the most significant trends of the 2010s were already very visible in 1999 or even 1989. Still, some long-wave trends have greatly accelerated during the last 15 years.

The most significant acceleration can be observed in communication technologies. According to the latest data, in 2015 the number of mobile communications users exceeded 7 billion people while in 2000 their number was just about one billion. Not only urban but also rural residents use Wi-Fi. They can reach any place in the world from the comfort of their own homes.

The 2000s saw the emergence of technologies able to strengthen our relations. In 2010, Facebook became the most visited website, even though in 2000 it simply did not exist. The same trends can be observed in modern mobile communications technologies. They do not try to replace our personal communication. Instead, they aim to extend and deepen our communication opportunities for keeping in touch with people far away.9

In addition to providing individuals with personal communication links around the world, mobile devices enable us to instantly retrieve information, answer questions, or get directions to the nearest Mexican restaurant in seconds. Social media sites have also revolutionized personal communications and the way we receive and disseminate information. Of course, all this is made possible by the Grand Master of the change parade over the last few decades—the Internet. Instant communications and information and countless other innovations made possible by the Internet have created what can legitimately be termed a “mega new normal.”

Long-wave changes such as the Internet’s impacts on information and communication, unfold over years or decades. While it can be harder to comprehend their full nature and ultimate impacts, at least we have time to adapt to them. On the other hand, the COVID-19 pandemic struck virtually overnight and peaked in a few weeks, making it painfully obvious but more difficult to respond to so quickly. Communities face these challenges constantly. Events such as the loss of a major employer with economic and social impacts comparable to the pandemic can happen any time to a community. As case studies and examples in this book show, cities or regions prepared to respond to these shocks using the tools of good community and economic development can rebound and, if necessary, reboot more quickly and successfully than communities caught unprepared can. Using tools such as community assessments and strategic planning, these communities are positioned better to respond to both short- and longer-term changes.

Rebooting Downtown Allentown, Pennsylvania

When traditional employers including Bethlehem Steel and Mack Trucks closed or downsized, Allentown fell from prosperity into decline. The downtown retail district, which included the popular Hess department store, was particularly hard hit, and pawnshops and boarded up storefronts started to proliferate. This spurred planning and cooperation between the public and private sectors, and, with support from the state, downtown Allentown underwent a renaissance. The City Center area now features a hockey arena, new office space, museums, art galleries, and a growing residential sector.

A catalyst for the renaissance of downtown was the creation of a Neighborhood Improvement Zone (NIZ) through legislation passed by the state in 2009. Under this program, nonproperty state and local taxes generated in the 130-acre downtown NIZ are invested back into the area instead of going to state and local general revenue coffers. Some of this money is used to subsidize private sector development, which allows developers to charge lower rents, thus attracting businesses and residents to the downtown area. The NIZ money also helps support public services in the area. The NIZ program has helped bring thousands of new jobs and over $1 billion in investment to City Center Allentown. The jobs vary from entry-level positions in the retail and hospitality sectors to professional jobs in companies such as the Lehigh Valley Health Network, CrossAmerica Partners, and the BB&T (now Truist) Corporation.

The Urban Land Institute cited the renaissance of downtown Allentown as an excellent example of success through public-private collaboration, strong leadership, entrepreneurial spirit, and a clear vision for the future. Local and state politicians set aside differences to help make the NIZ program a success. “Partisanship has to be set aside if we’re going to solve the problems of challenged cities,” stated one elected official. US News now ranks Allentown as one of the eight best places to live in Pennsylvania. The Allentown story is a good illustration of a community pulling together to address the problems brought on by the decline of local industries and other adverse trends. Allentown adjusted to its own “new normal” and forged a path toward prosperity.10

From Pandemic to New Normal

Has the COVID-19 pandemic created a new normal? It would be questionable at this point to equate the effects of the pandemic to the long-wave transformational changes enabled by the Internet, but the COVID-19 saga is far from over. Variants that are even more infectious have appeared in places around the world and spread quickly. Some infectious disease experts have predicted that the COVID-19 virus and its variants will remain a significant public health threat for the foreseeable future. Furthermore, there is concern and speculation that long-term social and economic impacts of the pandemic could last for years or decades.

The COVID-19 pandemic had a pervasive impact on many aspects of society in countries around the globe. The millions of deaths and tremendous economic damage, including lost output, mass unemployment, and permanent business closures, are painfully obvious. Other impacts such as disruptions in education and mental health issues may not be as visible yet, but they may prove to be just as significant in the long run. The Harvard Gazette consulted faculty experts across specialties to help identify impacts of the pandemic that may continue to affect society long after the medical emergency subsides and economic output recovers.11 Dr. Karestan Koenen, the professor of psychiatric epidemiology at the Harvard School of Public Health, cites several impacts of the pandemic on the “COVID-19 generation” with potential long-term effects:

• Uncertainty and uncontrollability regarding many of life’s major milestones such as entering school, graduating, getting a job, and even getting married and having children.

• Physical distancing and isolation, encouraging people to rely more on social media and less on in-person socialization.

• Isolation and curtailed activities that interfere with developmental opportunities for young people to try new things, learn from experiences, and acquire new skills.

Dr. Koenen concludes that “While it’s likely that the coming-of-age generation will bear long-term impacts (from the COVID-19 pandemic), it’s less clear what those might be.” She believes the pandemic’s traumas could lead to a rise in hopelessness and higher levels of anxiety and depression that could continue for years to come. Furthermore, some people who have had the COVID-19 virus experience continuing long-term effects such as fatigue, lung problems, brain fog, and other symptoms.

Economic Impacts: The Job Market and Labor Force

A report by the McKinsey Global Institute based on surveys of top business executives in eight large-economy countries provides useful insights into the potential long-term impacts of the pandemic on businesses and their employees.12 As shown in the accompanying box, the report concludes that the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated three broad trends that could affect work and how it is done on a long-term basis: (1) the shift to remote work and virtual interactions; (2) a surge in e-commerce; and (3) the deployment of automation and artificial intelligence.

The Future of Work After COVID-19

This study by the McKinsey Global Institute classifies occupations and industries by the degree to which their operations require physical proximity and therefore less opportunity for decentralized or remote work. For example, occupations in the “work arenas” of health care, personal care, and retail had high physical proximity scores, while occupations involving computer office work, transportation of goods and outdoor production, and maintenance had low physical proximity scores. The study identified three long-term trends that could be a legacy of the COVID-19 Pandemic:

1. Shift to Remote work

• Only a portion of jobs lend themselves to remote work. “Considering only remote work that can be done without a loss of productivity, we find that about 20 to 25 percent of the workforces in advanced economies could work from home between three and five days a week. Advanced economies, with a greater share of jobs in the computer-based office arena, have a higher potential for remote work than emerging economies.”

• The share of all jobs that can be done remotely without loss of productivity is higher than before the pandemic. Because of the forced learning curve, it is four to five times higher.

• A reduced number of employees working in offices could have multiplier effects. Thirty percent of executives surveyed by McKinsey planned to reduce office space by an average of 30 percent. With fewer regular office workers, the demand for nearby restaurants and retail and also public transportation may be negatively affected.

• Where people do remote work could have significant but differing implications for cities and towns of all sizes. The prepandemic trend of a disproportionate share (relative to population) of job growth going to large cities could be reversed. Office vacancy rates in 2020 increased by 91 percent in San Francisco and by 32 percent in London, while they declined in smaller cities such as Glasgow, Scotland, and Charlotte, North Carolina. Some companies are considering opening more satellite offices in lower-population areas to facilitate remote work and attract workers who live there.

• The pandemic appears to have encouraged a migration in some areas from larger urban areas to smaller cities and urban areas. Data from LinkedIn analyzed by McKinsey show that more members moved from larger cities to smaller cities in 2020 than in 2019. The LinkedIn data also show that large metro areas such as New York City; the San Francisco Bay Area; Washington, DC; and Boston had a greater decline in the inflow-outflow ratio than smaller cities such as Madison, Wisconsin, and Jacksonville, Florida.

• The increased use of videoconferencing and other remote means of communications brought business travel to a virtual standstill at the height of the pandemic, and it may not recover to prepandemic levels for several years. McKinsey estimates that a 20 percent decline in business travel may persist after economic recovery from the pandemic. This would have a lasting impact on travel-related industries.

2. Increased use of e-commerce and other virtual transactions.

• In 2020, the share of e-commerce in retail sales grew across their surveyed countries by a rate of two to five times the rate than before the pandemic. In the United States, its share grew by 4.6 percent compared to an annual average growth over 2015 to 2019 of 1.4 percent.

• Significant growth during the pandemic has also occurred in virtual transactions including telemedicine, online banking, and streaming entertainment. This trend has encouraged growth in jobs in sectors such as warehousing, transportation, and delivery while contributing to declines in in-store jobs such as cashiers. Some retailers such as Macy’s and Gap are closing brick and mortar stores, but e-commerce related companies like Amazon are adding facilities and employees (400,000 hired during the pandemic).

• These changes could lead to more gig or freelance workers in these growing employment sectors. They may also have significant implications (positive or negative) for the economic health of communities who have larger numbers of workers in these affected sectors.

3. Faster adoption of automation and artificial intelligence

• In periods of increased pressure to reduce operating costs such as recessions, research indicates that many businesses tend to adopt automation technologies and redesign work processes. The McKinsey survey showed that two-thirds of the responding senior executives said they were stepping up automation and artificial intelligence in their operations.

• An increasing trend toward automation and artificial intelligence is likely to have a larger negative impact on lower-skilled workers.

The report goes on to identify the following potential impacts of this new normal on the labor force:

• Almost one-third of the U.S. labor force will be more footloose, able to do most of their work effectively at remote locations. For the computer-based office work arena (including occupations such as accountants, lawyers, financial managers, and business executives) that accounts for 31 percent of the U.S. labor force, the study estimates that 70 percent of work time can be spent at remote locations without losing effectiveness. In most other work arenas more closely tied to a job site, as little as 5 to 10 percent of work can be effectively done remotely. The upshot is that the COVID-19 new normal may feature a different mix of occupations driven by the previous three trends. The study predicts that by 2030, the share of total employment in many countries will be higher compared to the prepandemic situation in sectors such as health care workers and STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) workers and lower in occupations such as office support, production and warehousing work, and customer service and sales.

• Almost all labor demand growth will be in high-wage occupations. More low-wage workers will have to find new jobs, but since low-skill jobs will not be growing, many will have to transition to higher-skilled positions. This will require more social and emotional skills as well as technical skills and more occupation-specific training resources at the national and local levels.

Trends identified in the study such as migration from large urban areas to rural and smaller metro areas along with development of tools to facilitate remote work are game changers. If the pandemic has accelerated these trends as the McKinsey study suggests, then it may have indeed helped create a lasting new normal and pattern of work.

The New Geography of Work

In the time-honored real estate mantra “location, location, location,” the word is repeated to emphasize the advantages of one place. Perhaps now we should repurpose the phrase to indicate the advantages of three related places—where the remote worker lives, where the boss lives, and where the physical office (if there is one) is located.

The McKinsey study offers compelling evidence that increased reliance on remote work may be a lasting legacy of the COVID-19 pandemic. Other surveys and studies support this conclusion. Corporate real estate executives and business location consultants are two groups of professionals positioned well to observe first-hand how the COVID-19 pandemic has influenced remote work and the use of company facilities. Corporate real estate executives manage a company’s existing facilities and help plan for future office and production space requirements. Business location consultants help companies find the best locations for new facilities across countries, states, and communities.

CoreNet Global, a professional association of corporate real estate executives headquartered in Atlanta, surveyed its members in January 2021 concerning the lasting effects of the pandemic on work and facilities in some of the world’s leading companies.13 These findings are listed in the accompanying box.

CoreNet Global Survey on Effects of Pandemic on Remote Work and Corporate Facilities

Some key findings:

• Decreased Corporate Footprint: 33 percent of respondents project that by 2022 the company’s overall real estate footprint will have shrunk by between 10 and 30 percent.

• Work Hours: 69 percent responded that the 9 to 5 work pattern is a thing of the past.

• Hiring Remote Employees: 57 percent responded that their companies would consider hiring employees regardless of location.

• Where the Work Will be Done: On average, the respondents reported that in the future 46 percent of the typical work week will be in a traditional office, 43 percent at home or another remote location, and 11 percent in a co-working environment.

• Corporate Satellite Locations: 16 percent responded that their companies would be opening satellite offices closer to where employees live.

• Reshoring: 53 percent of respondents projected an increase in reshoring by their companies, with 81 percent reporting that it would occur in North America.

The CoreNet survey paints a picture of a postpandemic new normal where flexible remote work will be much more common, and new employees will not necessarily have to live within commuting distance from their offices. As a result, companies will need less space and will reduce their real estate footprint, and some will move closer to where their employees live. Under this new geography of work, company facilities and operations are likely to be more spread out and even follow their employees. This is certainly a movement away from the old model of companies and their workers locating in close proximity to each other to accommodate the daily commute. This traditional model encourages clustering of companies and employees in larger metropolitan areas and contributes to traffic congestion and air pollution.

A survey of business location consultants by Site Selection magazine in late December 2020 further illustrates the trend toward a new geography of work.14 In an article aptly entitled “Instead of People Chasing Jobs, Jobs Are Now Chasing People,” Site Selection reported that 83 percent of survey respondents indicated that increased reliance on remote work is having some effect or a significant effect on the facility location decisions of their client companies. The Site Selection article states that “companies are realizing they no longer have to remain in large and costly city centers,” citing the result that 51 percent of survey respondents said their companies were considering moving their business operations away from city centers to suburbs and rural locations.

Of course, the future is notorious for not accommodating predictions. The social and economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and the new normal it might engender is subject to much speculation. The surveys and studies cited previously and others indicate that the social and economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, possibly along with other trends already in the making, will help create a new geography of work with potentially significant changes in where work gets done and where companies and employees choose to locate. In fact, companies such as Nationwide, Twitter, and JPMorgan Chase have already introduced permanent work-from-home policies. The pandemic certainly created a new normal for work in the short run, and there is considerable evidence that it will have long-lasting effects in many sectors and areas.

Challenges and Opportunities for Communities

Janus is the Roman god symbolizing change and transition to a new state, such as from the past to the future or from one vision to another (Figure 1.5). Janus is associated with new doorways to the future and new opportunities, and that’s why the first month of the year is called January.

He is usually depicted as having two faces, one looking backward to the past and the other to the future. Janus is a fitting symbol for community change and progress. Change brings uncertainty and usually some measure of risk. Therefore, some communities may be hesitant to embrace change and look for new opportunities. Sometimes, communities are afraid that a change will threaten their identity and heritage—the things that have made them unique. However, successful communities are able to blend change and new opportunity with the assets and characteristics that have served them well in the past. Just like Janus, they are looking toward the future with an appreciation for the past.

Figure 1.5 Janus: The Roman god of new beginnings

Source: www.britannica.com/topic/Janus-Roman-god

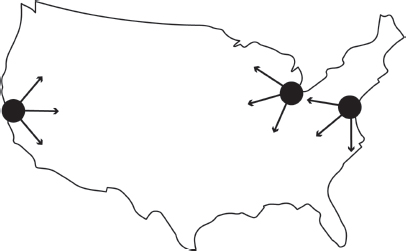

It is often said that change brings opportunities as well as challenges, and the COVID-19 pandemic is no exception. For less-populated areas—smaller cities and rural areas—there may be opportunities to gain benefits from the outmigration from larger metro areas. Mymove.com analyzed change-of-address data from the U.S. Postal Service to determine the extent and nature of the outmigration.15 They found that in 2020, the year of the pandemic, 15.9 million people filed a change-of-address form, representing a nationwide increase of 4 percent over 2019. However, the data show that outmigration from major cities such as New York, Chicago, and San Francisco (Figure 1.6) was significantly higher in 2020 than in 2019. Outmigration increased in San Francisco by almost 300 percent in 2020 over 2019. On the other hand, cities where in-migration increased in 2020 over 2019 include smaller cities such as Katy, Texas (population 26,909); Meridian, Idaho (101,905); and Leander, Texas (75,976).

People move from larger cities to smaller ones for a host of reasons such as a lower cost of living and, for them, a better lifestyle. A recent survey by the Pew Research Center of 10,000 U.S. movers revealed that 28 percent cited fear of getting COVID-19 in their current location as the reason for moving and 18 percent cited financial reasons including job loss which, given the huge economic shock of the pandemic, might have been COVID-19 related.16 Big Technology, a newsletter covering technology industries, analyzed the relocation patterns of technology workers to determine which cities had gains and which had losses in this important segment of the workforce.17 Using inflow over outflow ratios as a measuring tool, they found that cities such as Madison, Wisconsin, and Hartford, Connecticut, had positive net inflows while cities such as Boston and the San Francisco Bay Area had positive net outflows. This relocation trend by tech workers probably reflects the decisions of some large employers such as Facebook and Google allowing some employees to work remotely on a permanent basis.

Figure 1.6 Outmigration from New York, Chicago, and San Francisco

There is evidence that a trend away from big cities toward smaller cities and rural areas was gaining steam even before the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2019, the Public Broadcasting System (PBS) cited data showing that collectively U.S. cities lost nearly 300,000 millennials in 2018—the fourth consecutive year that cities lost some of these productive workers aged 24 to 40.18 The PBS also cited a 2018 Gallup Poll showing that two-thirds of respondents would prefer to live in a rural area, small city, or town, while only 12 percent would prefer to live in a big city.19

If more skilled workers are moving to smaller cities and rural areas, are companies following them? Unfortunately, data regarding the movement of employers are harder to obtain. Still, the surveys cited earlier from corporate real estate executives (CoreNet) and business location consultants (Site Selection magazine) indicated that many companies do expect to relocate away from metro areas to smaller cities and rural areas.

An increase in a community’s workforce, especially skilled workers, can offer a community many potential economic development benefits. Local businesses will have a deeper and richer labor pool to draw from, and a community can become more attractive to companies looking for a new location. A growing population and expanding workforce contribute to the local economy through activities such as buying a home, eating in restaurants, and shopping in local retail stores. Furthermore, there are many examples of highly skilled workers such as engineers and computer scientists putting down roots and starting businesses in their new communities.

Recognizing the advantages of a robust labor supply, some communities have established programs to attract workers through incentives such as cash stipends, free co-working space, and housing allowances. The Northwest Arkansas Council offers $10,000 and a free bicycle to entice remote workers to move to Benton or Washington counties in the northwest part of the state. Most of these enticement programs are aimed at a particular audience, such as technology workers, and have specific qualification requirements. Hamilton, Ohio, will offer up to $10,000 to recent college graduates to move to certain parts of the city. Natchez, Mississippi, offers $6,000 to remote workers with their “Shift South” initiative to relocate to their historic city where housing prices are quite affordable in comparison to other parts of the United States. Other cities with worker recruitment programs include Tulsa, Oklahoma; Savannah, Georgia; Baltimore, Maryland; and New Haven, Connecticut. These programs target individuals with degrees in science, technology, engineering, or mathematics. Sometimes preference is given to those who have a desire to give back to the community through activities such as restoring a historic property or starting a new business.

Some states and countries (e.g., Vermont and Chile) also offer relocation incentives to targeted workers. Ironically, these worker attraction programs are the mirror image of the historical norm of offering incentives to entice companies to move to the community. More communities, states, and countries are realizing that building a strong workforce can be a better way to attract outside investment and encourage new enterprise startups. And if the speculation that more employers will be following people as a result of the new normal, then all the more reason to build a strong workforce.

Is Your Community Remote Work Friendly?

While the COVID-19 pandemic compelled many companies to temporarily adopt remote work where possible, many will continue the practice indefinitely because of newfound benefits to the employer and employee. Notably, leading technology companies such as Google and Apple have announced a permanent remote work model for some employees. As a result, companies and workers have more latitude in their locational choices. Many companies are now less tied to population centers and therefore can consider lower-cost locations. Workers are also freer to move to areas with a lower cost of living, better recreational opportunities, and other attributes they may prefer.

This new geography of work may provide community and economic development opportunities for some locations. Remote workers are often highly educated, well-paid professionals whose incomes and expenditures can help boost a local economy and create jobs. Likewise, remote work companies are often in growing knowledge-based service industries that can expand and diversify a local economy. Because of their appeal, attracting remote work companies and workers is highly competitive.

Communities that are remote work-friendly may be able to gain a competitive advantage in attracting remote work companies and workers. These places have good telecom service, endorse and encourage remote work, and offer a business community and workforce experienced in and supportive of remote work. Remote work-friendly should be demonstrated and preferably certified by an independent third party.

Community certification labels such as “development ready” or “available inventory of suitable sites and buildings” granted by states or independent organizations have proven to be a powerful economic development recruiting tool. In the competitive site selection process, certification in these areas can reduce perceived risk and put a community on the location shortlist more quickly. Similarly, communities can gain a competitive edge in the new normal world of remote work by attaining a remote work-friendly designation.

Embracing the Future

Amidst its chaos and tragedy, the COVID-19 pandemic has encouraged us to consider some challenging questions. How long will the social and economic disruptions caused by the pandemic continue around the world? How will the COVID-19 new normal evolve? What is the likelihood that other pandemics or major shocks (e.g., financial or political) will materialize? Despite our focus on recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic and on the possibility of future shocks, opportunities in the new, new normal world are gaining our attention. The new geography of work may contribute to prosperity in some communities through more footloose companies and remote workers moving to them. It can also encourage community improvement to attract these companies and workers (becoming remote work friendly), which also benefits current residents.

Global shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic may be relatively rare, but local shocks such as the shutdowns of a major employer happen to some communities somewhere every day. They can occur without warning or they can be a predictable culmination of ongoing trends. The COVID-19 pandemic has served as a stark illustration that a change can occur anytime, and, hopefully, it has encouraged some communities to think about how to protect themselves from future disruptions and even leverage them to their advantage. Communities can prosper by creating a more diversified economy and becoming more adept at managing change.

The popular adage “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” is a colorful way of saying don’t mess with success. But, success can be ephemeral. If you follow this rule, then you wait for things to break before you take any action. But, therein lies the problem—they break. This is a reactive strategy. Who would recommend waiting until a car engine seizes up or the brakes fail to check the oil and brake fluid? A much better prescription would be, “If it ain’t broke, it will be, so you had better figure out how you’re going to fix it.” Better yet, “fix it before it breaks.” In other words, plan and act proactively; don’t just sit around waiting for the old normal to return because it might be gone forever.

How prepared is your community to cope with evolving economic and social trends, or better yet, take advantage of them? Do your elected officials, stakeholders, and fellow residents view change as an opportunity for growth and prosperity or as a Frankenstein monster? Has your community established a vision and plan for the future, or are you just drifting with the current, oblivious to the rapids and waterfalls ahead? In short, how prepared is your community to reboot and prosper? For most communities, prosperity is not anointed; it is earned by understanding and using the tools in the community and economic development best practices toolbox.

Prosperous Community Toolbox

Read, Reflect, Share, and Act

Chapter 1 is about change and how communities respond to it. Ironically, the COVID-19 pandemic served as a kind of fire drill showing communities everywhere what can happen almost overnight to disrupt the local economy. It is useful to reflect on how the actions taken to address the pandemic can serve as “lessons learned” for a better community response to future economic challenges. The goals of the tools for Chapter 1 are to assess how your community responded to the pandemic, and to assess small business assistance programs in your community and its remote work “friendliness” that can help with recovery and economic growth.

1.1 In your Community Action Groups, discuss and assess the ways the COVID-19 pandemic (or other crises) affected your community. Will there be long-term effects on your community? If so, what? What opportunities have been created? Do a self-assessment (conduct a community survey if you like) of how your community reacted to the COVID-19 pandemic. How did local governments, community and economic development agencies (including chambers of commerce) and other civic organizations participate?

1.2 Inventory the businesses recovery and assistance programs in your community. Does your community have small business assistance or mentoring programs? How can the community assist the owners/managers of closed businesses and other entrepreneurs to start new businesses?

1.3 Determine how remote work friendly your community is. Download our list of factors that help make a community remote work friendly. Use the list to get an idea for how remote work friendly your community is and how you can improve.

Visit https://www.prosperousplaces.org/rebooteconomics_toolbox/ to download the Chapter 1 tools.

1 H. Wood. 1918. A Wise, “Beware!” in N.E.L.A. Bulletin 5, pp. 604–605, National Electric Light Association.

2 www.politico.com/news/2022/03/09/new-normal-forces-nato-rethink-security-00015714

3 N.A. April 01, 2021, “2021 State of the Union Facts,” USAFacts, https://usa-facts.org/state-of-the-union/

4 N.A. October 13, 2020. “Economic Development in the New Normal,” ProsperousPlaces.org, www.prosperousplaces.org/2020/09/14/economic-development-in-the-new-normal/

5 “COVID-19 to Slash Global Economic Output by $8.5 Trillion over next Two Years | UN DESA Department of Economic and Social Affairs,” United Nations (United Nations), www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/policy/wesp-mid-2020-report.html (accessed April 05, 2021).

6 [email protected]. February 25, 2021. “COVID-19 Travel Industry Research,” U.S. Travel Association, www.ustravel.org/toolbox/covid-19-travel-industry-research

7 N.A. February 2, 2021. “Amazon Profits Increased Nearly 200% with COVID-19: Research FDI,” ResearchFDI https://researchfdi.com/amazon-covid-19-pandemic-profits/

8 A. Klein, and E. Smith. February 05, 2021. “Explaining the Economic Impact of COVID-19: Core Industries and the Hispanic Workforce,” Brookings, www.brookings.edu/research/explaining-the-economic-impact-of-covid-19-core-industries-and-the-hispanic-workforce/

9 “Your Editorial on Culture & Creativity,” April 30, 2018, www.culturepartnership.eu/en/article/top-9-trends-of-the-last-decade

10 J. Tierney. 2021. “Breathing Life Into Allentown: Pennsylvania Comes To The Rescue,” The Atlantic, www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/09/breathing-life-into-allentown-pennsylvania-comes-to-the-rescue/379742/ and N.A. 2021. “Turnaround Towns,” Carnegie UK Trust, www.carnegieuktrust.org.uk/project/turnaround-towns

11 N.A. 2021. “Our Post-Pandemic World And What’S Likely To Hang Round,” Harvard Gazette, https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2020/11/our-post-pandemic-world-and-whats-likely-to-hang-round/

12 2021. www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/the-future-of-work-after-covid-19.https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/the-future-of-work-after-covid-19

13 N.A. February 10, 2021. “The Pandemic’s Effect on Corporate Real Estate,” CoreNet Global News Release.

14 R. Starner. n.d. “Site Selectors Survey: 5 Ways COVID-19 Changed Site Selection: Site Selection Magazine,” Site Selection, https://siteselection.com/issues/2021/jan/site-selectors-survey-five-ways-covid-19-changed-site-selection.cfm (accessed April 05, 2021).

15 N.A. February 17, 2021. “Coronavirus Moving Study Shows More Than 15.9 Million People Moved During COVID-19,” MYMOVE, www.mymove.com/moving/covid-19/coronavirus-moving-trends/

16 K. Alex. December 17, 2020. “Where Tech Workers Are Moving: New LinkedIn Data vs. the Narrative,” Big Technology, https://bigtechnology.substack.com/p/where-tech-workers-are-moving-new

17 C. D’Vera. January 13, 2021. “About a Fifth of U.S. Adults Moved Due to COVID-19 or Know Someone Who Did,” Pew Research Center, www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/07/06/about-a-fifth-of-u-s-adults-moved-due-to-covid-19-or-know-someone-who-did/

18 “Why Millennials Are Moving Away From Large Urban Centers,” 2021. PBS Newshour, www.pbs.org/newshour/show/why-millennials-are-moving-away-from-large-urban-centers

19 Gallup, Inc. 2021. “Americans Big On Idea Of Living In The Country,” Gallup.Com, https://news.gallup.com/poll/245249/americans-big-idea-living-country.aspx