Building a Prosperous Community

“We almost hit the point of no return,” the mayor of Osceola, Arkansas told The Wall Street Journal in 2006. Like many rural communities, Osceola, a town of about 7,000 in Northeast Arkansas’ Mississippi County, grew up around the agriculture industry. As farm employment declined, textile-manufacturing jobs grew but ultimately disappeared as the industry moved offshore. In 2001 Fruit of the Loom shut down its Osceola plant leaving 2,500 people unemployed and the community in a crisis. Not only was unemployment rampant, the school system was classified as academically distressed and faced a state takeover. But what a difference a few years and an all-out community effort can make! Today Osceola has a strong economy supported by successful companies such as Japanese auto parts manufacturer Denso and Big River Steel with its $1.3 billion technologically advanced flat-rolled steel plant employing over 600 people. How did Osceola and Mississippi County reboot the local economy? You can skip to the end of the chapter for the rest of the story, but we encourage you to read the chapter first to fully appreciate this example of community resilience.

As discussed in Chapter 3 and illustrated by numerous examples throughout the book, how well a community engages in the community development process can be a key determinant of its community development outcomes. This includes strengthening the four community components on the roadmap to prosperity: basic needs, quality of life, social needs, and the economy. The community development process can improve the provision of basic needs such as public safety and education, and enhance the quality of life through citizen involvement, advocacy, and financial support. The cornerstone of the community development process is involvement and leadership, thus helping residents meet their social needs and feel more attached to the community. But, how does the community development process contribute to the fourth prosperous community component, the local economy? This question is the primary focus of this chapter and a central theme of the book.

You Want a Prosperous Community? Show Me the Money!

When Liza Minnelli sang, “Money Makes the World Go Round” in the 1972 movie Cabaret, she coined a phrase that persists to this day and provides a basic lesson in economics (if only we could all learn economics through song!). Money and its equivalents are the lifeblood of commerce, and it does make the economic world go round. Let’s start with the premise that more money is better than less. On a personal level, more income coming in than going out would make us feel more prosperous. Personal cash flow can vary considerably in the short run due to things such as such as getting a bonus or buying a car, but over the long run if cash flow is positive, then wealth is growing.

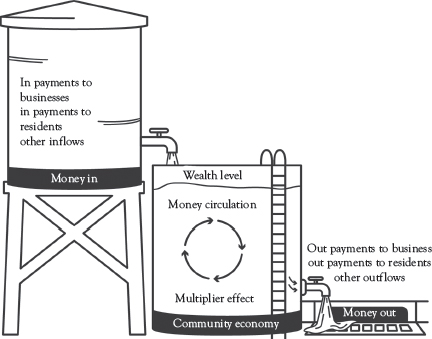

This is also the case with inflows and outflows of money at the community level. Local residents, businesses, and other stakeholders in a community have their own net inflows or outflows of money, and the sum of all those can be considered the community’s cash flow. If it is positive, the level of total wealth in the community rises as illustrated in the accompanying box. Money enters the community through businesses selling their goods and services to outside consumers, direct payments to residents from out-of-town sources, and in miscellaneous other ways. Money leaves the community when businesses pay out-of-town suppliers and shareholders, and residents spend money outside of the community shopping and vacationing.

Figure 4.1 Community money flow and wealth

Figure 4.1 is a simple model of money flow and wealth for a community. The level of water in the tank represents total community wealth. Water (money) flowing into the tank raises the level of wealth, and water flowing out of the tank lowers it.

Money flows into the community tank from these sources:

• In Payments to Businesses: Local businesses sell goods and services to buyers outside the community, receive payment, and then pay employees and local suppliers. Businesses involved in tourism and hospitality are included in this category. When tourists visit, they spend money in restaurants, hotels, retail stores, and other places. Businesses and other organizations (e.g., nonprofits) that bring outside money into the local economy are often referred to as export businesses. It’s important to note that in this context, export means anywhere outside of the community, not necessarily out of the country. Businesses that sell goods and services, mainly to community residents, can be referred to as local market businesses. For example, a hardware store selling mainly to community residents in a small town would be considered a local market business, whereas a Home Depot that pulls in customers and money from surrounding communities would be considered an export business.

• In Payments to Residents: Residents receive money from numerous outside sources such as retirement payments, investment income, and now increasingly from employers outside the area for residents engaged in remote work.

• Other Money In: Federal or state government installations and offices, nonprofits, and other miscellaneous organizations receive money from outside sources. Note that local government facilities and operations do not typically increase the water level very much in the tank. Local governments are more cash flow neutral because the money they spend in the local economy mainly comes from the local money they take out of it through taxes.1

Money flows out of the community tank through these sources:

• Out Payments by Businesses: Local businesses purchase raw materials and intermediate goods as well as services from outside suppliers to produce their own products and services.

• Out Payments by Residents: Residents make payments to outside sources when they shop online or in surrounding towns, eat in nonlocal restaurants, take vacations, pay tuition for out-of-town colleges, and a host of other activities.

• Other Money Out: Local governments and other local organizations purchase goods and services from out-of-town providers. Residents and businesses pay taxes to federal and state governments.

As Figure 4.1 also portrays, money circulates inside the community as businesses, residents, and governments sell and purchase goods and services to and from local sources. This gives rise to the economic multiplier effect. Let’s say, for example, that a local manufacturing company lands a large new out-of-town customer and hires 100 unemployed workers to increase production. These 100 new workers will then purchase more local goods and services with their increased income (buy a car, eat out more often, or maybe even buy a house). This income that is recirculated within the community, in turn, stimulates additional local employment and income to satisfy the increased demand, and then the cycle repeats itself.2

The community cash flow model in Figure 4.1 illustrates two simple but important concepts for community prosperity:

1. Positive cash flow. If a community’s cash flow is positive over time (money in exceeds money out), the water level in the tank rises, and total wealth increases. If wealth increases faster than the population, then per capita wealth grows.

2. Keep money in the community. Keeping money circulating in the local economy and not going out keeps water in the tank and increases community wealth.

These two simple concepts help explain many of the economic development activities undertaken by communities:

• More businesses in a community selling their products and services to customers outside of the area bring in more money to support more local jobs and incomes. More inflow and jobs can be created by recruiting new businesses into the community, helping local businesses expand, and stimulating new business startups. The same applies to governments or organizations in the “Other In” category.

• Outside payments coming into residents also support local jobs and incomes because recipients spend some of it locally. Some communities promote themselves as a good place to retire for this reason.

• Reducing outside payments by local businesses helps keep money in the local economy and increases total wealth. Programs to encourage more local sourcing of raw materials and intermediate goods can help. The same applies to government or other organizations included in “Other Out.”

• Reducing outside payments by residents also keeps money in the local economy. This is the philosophy behind “buy local” campaigns by chambers of commerce and economic development agencies.

In the movie Cabaret, how much did the Kit Kat Klub contribute to local economic development and community prosperity in 1920s Berlin? We do know that out-of-town patrons would have contributed to the community’s money in flow, and if the club procured its supplies locally, that would help keep money circulating in the local economy. Beyond that, we can only speculate on the club’s impact on the local economy (maybe more jobs for police?) and on other prosperous community components such as the quality of life. We leave that to the reader’s judgment.

Economic Development as an Outcome

When a new company selling to out-of-town customers begins operations in a community, when an existing company expands or tourism increases, more money flows into the community creating more jobs. This puts cash in people’s pockets to buy groceries, clothes, haircuts, and countless other goods and services in the community, thereby creating even more jobs through the economic multiplier effect. As businesses continue to expand and more jobs are created outward signs of prosperity begin to appear—more industrial, commercial and retail buildings, more houses, and more restaurants. These are the outcomes of economic development. However, as the accompanying box explains, economic development can mean different things to different people and different communities, reminding us of the observation in Chapter 2 that economic development can either happen “to you” or “for you.” Taking the proactive approach of defining and pursuing preferred economic development outcomes helps communities avoid the “to you” and encourage the “for you.”

Is It Economic Development or Just Growth?

“We don’t need economic development, we need jobs!” proclaimed a small-town mayor over refreshments following a training session led by the authors. (Note for file: provide stronger libations at future seminars.) Actually, the mayor’s comment helps us think about what economic development really means. Perhaps, the mayor was thinking about some of his lower-skilled constituents—we can’t all be rocket scientists. He might view economic development as something that involves skilled workers in larger cities with new subdivisions, retail centers, and stadiums.

Some might say that economic development, like beauty, is in the eyes of the beholder, and there is some truth to that. For some small towns a new fast-food restaurant or dollar store can be a significant event that provides an additional dining or retail option as well as an employment opportunity. Newly hired employees probably wouldn’t care if you call it economic development or not—it’s still a paycheck to them. Residents of larger communities with bustling economies, however, might look at fast-food restaurants and dollar stores as just more sprawling growth and congestion and more stoplights. In such communities, the bar can be set pretty high. Anything less than a new technology firm with high-paying jobs might not be considered real economic development. Thus, the distinction between economic development and growth can very much depend on one’s perspective.

When we say a community is growing, what does that really mean? We can envision situations where growth occurs without meeting a higher standard of economic development, but it is hard to conceive of economic development without growth. More jobs and higher incomes will increase the demand for housing, retail, and personal services. As the authors travel around the country (physically or virtually), we sometimes encounter local officials who want a booming economy without the traffic lights and congestion—the economic development version of having your cake and eating it too. The Southern take on this usually goes something like “we want good jobs, but we don’t want to be like Atlanta,” a reference to the city’s legendary rush hour traffic jams. This is certainly an admirable goal, and perhaps the new normal of remote work is a tentative step in that direction. Remote workers, however, are not hermits—they still get out of the house to shop, dine, get a haircut, or visit friends. Smoothing out the peaks of rush hour traffic will ease congestion considerably, but for the foreseeable future, the main course of economic development with more jobs and higher incomes will continue to come with a side of orange road construction barrels.

Economic Development as a Process

Because we can learn much by example (sometimes referred to as “concept learning” by psychologists), we have included numerous stories of communities that have rebooted and prospered in the book. These communities are diverse in terms of size, location, and circumstances. The one thing they have in common is that, when faced with adversity, they did not simply wait for the next strong wind to push them off the shoals. Instead, they took decisive action to get themselves back on the journey to prosperity. Granted, a shock such as the downsizing or closing of a major employer can be a tremendous motivator, but all across the country and around the world communities are improving themselves simply because they want to do so.

As shown by the community wealth tank illustration in Figure 4.1, there are various ways to increase the flow of money into the local economy and decrease the outflow to create more economic prosperity. The inflow can be public or private money. Some communities are heavily dependent on public money to support the local economy:

• In Vermont’s capital of Montpelier, state government employees directly account for 29 percent of the city’s workforce and 32 percent of wages paid.3

• In Huntsville, Alabama, the Redstone Arsenal, a center for U.S. Department of Defense research and contracting, is estimated to directly and indirectly generate 90,500 jobs and $10.6 billion in economic output.4

Some communities are heavily dependent on a local college or university while others are retirement havens with large inflows of public and private pension payments.

Mostly, though, the private sector accounts for the majority of employment and income and constitutes the “backbone” of a local economy. In 2019, the private sector accounted for almost 64 percent of U.S. gross domestic product.5 In addition, communities generally have more influence in helping create private sector jobs through recruiting new businesses and encouraging new business startups. For these reasons, we focus mainly on private sector investment as a way to grow jobs and build prosperous communities.

Defining the Term

Now that we’ve characterized economic development as both a process and an outcome, let’s see how some economic development-related organizations define the term. Years ago, the American Economic Development Council (now merged into the International Economic Development Council) described economic development as:

The process of creating wealth through the mobilization of human, financial, capital, physical and natural resources to generate marketable goods and services … and benefit the community through expanding job opportunities and the tax base.6

The California Association of Local Economic Developers (CALED) offers a similar definition:

Economic Development is the creation of wealth from which community benefits are realized. It is more than a jobs program, it’s an investment in growing your economy and enhancing the prosperity and quality of life for all residents.7

These definitions emphasize the following:

• Creating wealth—not just making rich people richer, but giving everyone a chance to improve their economic situation

• Benefiting the community as a whole through creating opportunities and enhancing the tax base

• Investing in and mobilizing community resources to grow the local economy

• Affirming that the process of economic development leads to the outcome of economic development

Economic development is not just about jobs,—it’s about community prosperity.

Development Economics Versus Economic Development

The term economic development is also used in the context of developing countries:

Economic development … is the process whereby simple, low-income national economies are transformed into modern industrial economies.8

This important field of study is often referred to as development economics to distinguish it from economic development in industrialized countries. The latter is the subject of this book.

While many of the principles of community and economic development apply to both developed and developing economies, there are significant differences. A student from Niger taking a college course in community and economic development taught by one of the authors dropped by during office hours and lamented that he didn’t really understand the economic development part of the course. He said, “In parts of my country where there are no paved roads or infrastructure of any kind, economic development is only a dream; but I now understand better why we must concentrate first on community development.”

What Attracts Businesses to a Community?

To attract and retain more private sector investment and jobs, communities should understand what factors businesses evaluate when making location decisions and how they make them. As previously noted, retail stores and restaurants can be local market businesses or, when they attract out-of-town customers, export businesses. In some communities, especially those that rely heavily on tourism, the retail sector can be a major industry. However, the retail sector is not our focus here; there are other books and sources of information on retail location decisions. Instead, we focus on businesses that produce goods or services to sell to out-of-town customers (export businesses), thereby increasing the flow of money into the community.

As noted in Chapter 2 most companies naturally prefer communities that offer a good workforce, public infrastructure, educational system, and other factors they need to be profitable and grow. In addition, most business owners and decision makers would also naturally prefer to live in communities with a high quality of life for their own enjoyment and to help them attract and retain the best employees. A web search will turn up dozens of surveys of corporate executives and business location consultants on the factors that are most important to businesses when deciding where to locate or expand company operations. In a recent survey by Site Selection magazine, consultants listed the following as the most important location factors in order of priority:9

1. Workforce

2. Transportation infrastructure

3. Available sites and buildings

4. State and local tax structure

5. Incentives

6. Utilities

7. Regulatory environment

8. University and college resources

9. Cost of real estate

Surveys of this nature provide useful insights into how companies evaluate communities when making investment decisions, but they are generic whereas location decisions are unique. The location decision factors for a company looking for a new regional headquarters or other office facility would not be the same as those for a company looking to locate a new manufacturing facility. Workforce and education might be key factors for both, but the headquarters company is more likely to be looking for white-collar workers and higher education resources while the manufacturing company is looking for blue-collar production workers and technical training programs. Some business investment decisions are driven by very specific requirements. For example, food-manufacturing facilities often locate close to where the agricultural products are sourced—the raw materials for these facilities. The location decisions of warehouse and distribution facilities are often driven by logistics models that determine exactly where a new facility should go to fit into a complex distribution network.

Just as businesses in the expansion mode seek communities that meet their needs and help make them more profitable, so do existing businesses. Communities should not take for granted businesses that are already located there. Some recent high-profile moves of companies from California with its higher cost and regulatory burden to the Austin, Texas area, illustrate that local signature companies such as Hewlett-Packard, Oracle, and Tesla can be footloose. According to media reports, Elon Musk, owner of Tesla, announced that he would move his headquarters to Texas or Nevada immediately after local governments refused to let the company reopen its Fremont (California) factory. Elizabeth Edwards, founder of Ohio-based H Venture Partners, stated, “The Silicon Valley exodus is real. It’s driven by a number of factors, taxes and the cost of living being two reasons.”10

At this point, you might be thinking that this whole business location thing seems pretty complicated and expensive, and asking “Do we have to improve our workforce, infrastructure and education at the same time? Even if we tried that, should we focus on technical training or higher education, highways, or internet service?” The answer to this important question can be found in the following phrase, variations of which have been attributed to people ranging from the Apostle Paul to Harvard Business School guru Michael Porter: “A person can’t be all things to all people.” Likewise, a community cannot be all things to all businesses. A more practical and successful approach to attracting more business investment is outlined in the following three steps.

1. Understand your community’s strengths and weaknesses and its competitive position.

Picture a new girl in school, Anna, going to softball practice to try out for the team. When the Coach asks her what position she plays, Anna responds that she can play them all. Needing players, Coach tries her out at shortstop, but Anna misses some grounders. In the next game, Coach lets Anna play outfield but she is no better at catching fly balls. Desperate for a pitcher for the next game, Coach lets Anna pitch, and to her great surprise, she strikes out the other side in the first inning. When Coach asks Anna why she didn’t just say that she was a good pitcher and make things easier for both of them, Anna responds, “I didn’t know what players you needed, and I wanted to make the team; and besides, I wasn’t sure I could pitch that well on a new team.” Had Anna been more self-aware and honest with Coach, she could have saved herself some embarrassment and perhaps saved the team some losses.

What “position” can your community play best? Community assessments, as mentioned in Chapters 2 and 3, are critical to answering this question. If your community has an experienced white-collar workforce and strong educational resources, perhaps it could be a good location for a company’s regional headquarters. If your community is strategically located on an interstate highway connecting major metro areas, it could be a good location for a distribution facility. If your community has a good inventory of potential or developed industrial sites with good utility services, then it could be a good location for a large-footprint manufacturing plant. But, like our softball player Anna, a community cannot play all positions and be all things to all companies. In our professional careers helping companies with their location decisions, we have received many proposals from communities that are obviously not a good fit for a particular project. This is a waste of resources for all parties involved and certainly does not generate any goodwill for the community.

2. Identify industries that are a good match for your community.

To find their target markets, communities identify industries or economic activities that would be attracted to their assets and not put off by their relative weaknesses. Several years ago, one of the authors helped a new commuter jet company find a location for a large production and test facility. Requests for proposals (RFPs) were sent to the economic development agencies for 18 states that met the initial geographic and weather requirements with specifications on the number of clear flying days and industrial sites close to a general aviation airport. Despite these clear up-front specifications, some unqualified communities still submitted detailed proposals, wasting time and generating no goodwill for themselves.

In addition to being a good locational match, communities should identify industries that are consistent with their vision. For example, a community might aspire to transition from its traditional manufacturing base to more technology-oriented industries. If the community has excellent educational resources and internet service, something like a technical support facility might be a good locational fit. Companies that are a good match for a community can run the gamut from goods and services producers to nonprofit organizations to remote workers. The process of matching communities and industries, sometimes referred to as target industry analysis, is not the same as the often-criticized industrial policy of picking “winning” industries to support with public resources. Instead, it is smart target marketing—the same common sense approach businesses take to identify customers that are more likely to buy their products. Like a company trying to sell meat to vegetarians, a community trying to attract companies for which it has no locational advantage is a waste of resources. There are additional screens such as historical and predicted future growth rates that communities can also use to identify industries and companies that are good targets to pursue. Companies in a growing industry are more likely to look for places to expand than those in a declining industry.

3. Strive to become an even better location for your community’s preferred and matching industries.

No community is perfect and no community has unlimited resources. Deciding how to allocate public money over many different community needs and desires is an imperfect democratic process. However, as discussed in Chapter 2, using community development principles, such as obtaining broad input and developing a vision for the future, can help communities maximize the benefits from public expenditures. Deciding on the nature and scale of economic development and the kinds of industries a community desires can also help with community planning and budgeting decisions. For example, if a community wants to attract advanced manufacturing companies, then its priorities should include developing suitable industrial sites and creating relevant technical training programs.

Of course, public budget decisions should not be based solely on economic development. Many other factors included in our roadmap to prosperity such as public safety (basic needs) and recreation (quality of life) should be considered. But, a strong economy can definitely help by generating more tax dollars that communities can use to help address a wide range of budget needs (Figure 4.2).

Figure 4.2 Targeting for Economic Development Success

The Economic Development Stool

Through our simple community wealth water tank illustration, we have seen that local businesses selling products and services to out-of-town consumers pipe money into the community, creating jobs and income. The question then becomes how to grow a community’s business sector and therefore increase prosperity. This can happen in three basic ways:

1. New businesses moving into the community;

2. Businesses already located in the community expanding;

3. New businesses forming in the community.

These elements can be considered the three legs of the economic development stool (Figure 4.3).

Figure 4.3 The three-legged economic development stool

What can communities do to strengthen these three legs? Some communities take a hands-off approach, reasoning that businesses are naturally attracted to them because they are endowed with the factors that businesses need to succeed such as a good workforce. There are indeed some fortunate communities that are natural magnets for businesses. However, ask anyone in marketing or sales if having a good product is all you need to generate revenues, and you’ll probably get answers ranging from “So why are they paying me?” to “Are you nuts? There are lots of good products out there that we compete with every day!”

Hollywood movie lines such as “build it and they will come” notwithstanding, having a good location for operating a business and a good place to live does not necessarily attract investment and generate economic development. As of 2019, there were 19,502 incorporated cities and 3,142 counties in the United States, many of them good “products” competing to attract private or public job-generating investments and grow local businesses through economic development organizations and chambers of commerce. For these communities, the three legs of the economic development stool are often referred to as: (1) business recruitment, (2) business retention and expansion, and (3) new business startups. There are numerous articles, books, websites, and other resources devoted to conducting these three economic development activities. Such detail is beyond our scope in the book, but here is a brief overview of each activity.

1. Business Recruitment

Most businesses or organizations, large and small, are dynamic—expanding or contracting depending on their markets and national economic trends. When large national or international businesses are growing and can’t expand in existing facilities, they search for new sites or buildings. They can do this with in-house personnel or seek outside assistance, usually business location consultants or industrial/commercial real estate companies. Often, the businesses or their consultants create RFPs specifying the required site or building characteristics and the required or preferred community characteristics. Since searching through thousands of sites would be like looking for a needle in a haystack, companies commonly send the RFPs to state or regional economic development organizations and ask them to screen and submit any communities that meet the location criteria in the RFP. Sometimes companies forgo the RFP process and just informally spread the word that they are looking for a place to expand.

Smaller businesses, sometimes independently owned, often search for an expansion site in a more informal fashion. They may directly contact representatives from nearby cities and counties to ask about available sites and buildings, or they may search economic development or real estate websites for listings.

Regardless of the size or nature of the company, the process of matching buyer (the company) and seller (the community) is a two-way street. Companies actively look for expansion sites, and communities should also actively advertise their available sites and market themselves as a good business location. Communities can promote themselves and create market awareness in a number of ways including regular contacts with state or regional economic development organizations that receive RFPs, advertising in industry trade magazines and other business publications, or directly contacting businesses that might be in the expansion mode. The following box provides more information on community marketing and business recruiting.

2. Business Retention and Expansion

Just because a business is already located in a community does not mean that, if it needs to expand, it will do so in its current location. The need to expand could be driven by growth of an existing product, development of a new product, or any number of reasons that could prompt it to search for an additional location or even consider relocating the entire company. The expansion or relocation decisions of existing companies can be based on “push” factors making their current locations less attractive. For example, a company may grow dissatisfied with the local workforce, educational resources, or, as occurred in the previously mentioned examples of companies leaving California for Texas, the overall business climate including taxes and regulations.

Proactive communities can identify and work with existing companies and encourage them to expand where they are and not in other communities. Common business retention and expansion activities include:11

• Identifying local companies that may be in the expansion mode or may be at a risk for relocation. This can be done in many ways including monitoring local companies for production fluctuations, new product development announcements, or signs of potential merger or acquisition.

• Working with local companies to help address any issues that may be driving them away from the community. For example, a community could help a company meet its requirements for skilled labor and specialized training requirements through establishing internship programs in local high schools or working in partnership with a local community college.

• Building appreciation and loyalty among local businesses for the community through, for example, industry appreciation banquets and newsletter articles.

• Regular visits to local businesses to identify issues and ways to address them. Economic development organizations frequently solicit volunteers to help with business retention and expansion efforts.

3. New Business Startups

Communities can encourage new business startups by providing assistance to them and becoming “entrepreneurial friendly.”12 New business assistance programs can include:

• Low-cost shared space or “incubator” facilities for startup businesses that can include administrative support, meeting rooms, or even production facilities such as test kitchens.

• Training programs in business fundamentals such as strategic planning, accounting, and finance.

• Mentoring programs matching successful, experienced (often retired) business leaders with entrepreneurs.

• Information and research on important topics such as product market opportunities and competitor analysis.

New business startup assistance can be targeted to industries for which a community has a comparative advantage. For example, Blue Ridge Food Ventures in Asheville, North Carolina has a mission to “provide infrastructure and technical assistance to enable small businesses entering the marketplace with safe and wholesome foods and natural products, thereby assisting in the creation of new businesses, new jobs, and new revenues for the region.”13

Marketing Your Community: Your Brand, Your Audience, and Your Plan

Marketing your community is similar to marketing a business or a product. Your community might be a competitive location for business, a wonderful place to live, and a great place to visit, but even the best communities need marketing to achieve their goals and realize their vision. This reality is reflected in the large number of community and state marketing messages that appear every day through advertisements, e-mails, or other media.

Marketing is how you get your message and story into the world in a way that connects. It starts with keeping your audience top of mind and creating content that provides them with real value. Branding is defining who you are—the picture you are painting for your target markets of what your community holds for them.

Before you market your community, you need to know who you are as a community (clarify your brand) and who you are speaking to, and then create a plan to get the message out. Remember, your brand is more than a logo—it includes all points at which your audience connects with your community and the feelings it evokes. These can be displayed through your website, written materials, and more. Your brand also includes your current reputation and how people perceive your community.

Your audience includes different people so it helps to place them in different categories so you can understand exactly whom you are speaking to.

• Your internal audience is your community—people within your own office or organization, elected officials, and, really, all residents. You must get alignment with your internal audience so there is consistency with the message you are sending out about your community, as well as to build and sustain support for community and economic development efforts.

• Your partners will include any person or organization that can help and benefit from your community marketing efforts. For example, local real estate companies may be marketing the community to attract new commercial or residential buyers; their message should reflect the community brand. Certainly, all community and economic development organizations should adopt the brand. Sending out the same message through brand consistency across organizations can greatly enhance the power of marketing efforts.

• Your external audience includes those you want to attract to your community, such as new residents and businesses or organizations that will give the local economy a boost, bringing new jobs and growth.

For your marketing to achieve the results you want, you need to have a plan. You wouldn’t start building a house without blueprints, so why try to market without a plan.

Your marketing plan should include the following elements:

• Your Audience(s)

• Goals: Goals bring clarity and help you focus your efforts so you’re doing what will help achieve your desired results rather than wasting time on efforts that don’t generate results. Don’t set too many goals. Two to four is a good place to start.

• Objectives: What you use to measure your progress and success. Define what success looks like up front. Not everyone will have the same definition.

• Strategy: The approach you take to achieving your goals.

• Tactics: The action steps or marketing tools you use to achieve your goals and objectives. These can include e-mail marketing, social media, print or digital ads, public relations, and more.

• Resources and Budget: This includes your financial budget as well as your connections that can help you get the job done.

• Schedule: The final step in creating a marketing plan is developing a schedule of all the elements you want to include to map out what your plan will look like over time. A schedule:

![]() Serves as a checks-and-balances system so you are creating a plan that is relevant to your organization and its stage of growth.

Serves as a checks-and-balances system so you are creating a plan that is relevant to your organization and its stage of growth.

![]() Allows you to be flexible when new opportunities come up or you realize something isn’t working.

Allows you to be flexible when new opportunities come up or you realize something isn’t working.

Marketing should be done with specific intention. Putting effort into branding your community and identifying the best target market groups is being intentional with your marketing efforts. It requires thinking about what you want people to do with the message you’re putting out into the world. When you market with intention, your message is more likely to resonate with your audience than if you just shoot from the hip, post a couple of messages on social media, and hope it connects with people.

Community Enterprise: Expanding the Economic Development Stool

Now that we’ve introduced and explained the three-legged economic development stool, let’s update this old model and metaphor. How? Let’s add a fourth leg and convert our stool into a bench. A bench with four legs (Figure 4.4) is going to be more stable in the long run. So, what is this fourth leg? It’s community enterprise. As we discussed in Chapter 3, community enterprise refers to actions by nonprofits, for-benefit private businesses, and the public/civic sector to develop entrepreneurial organizations. The focus of these enterprises also includes a community mission or benefit that will result from their activities. In some places, community enterprise, whether community supported or community owned, can be an important part of community prosperity.

Figure 4.4 The four-legged economic development bench

Actually, the other three legs of our economic development bench (the three legs of the original stool) can also be considered community enterprise. Communities provide many of the factors that established businesses and new business startups need, such as utilities, roads, education, and other public services. Communities often provide industrial and business parks where they can locate. In addition, communities sometimes offer tailored services, such as road or water and sewer line extensions, or labor training programs, as the part of an incentive package to win the site-selection competition over potentially hundreds of communities. In so many ways, successful economic development, and therefore community prosperity, results from a partnership between the private and public sectors. The private sector invests capital into the community, creating jobs, incomes and tax revenues, and the public sector supports that private investment by providing a prosperous-ready community. For some communities, the road to prosperity might be a little shorter and faster if they understood this partnership better.

Delivering Economic Development Services

In a course taught by the authors a few years ago, an elected official raised her hand and said, “Okay, I get it—the community development process helps build a prosperous-ready community and then economic development builds on that to help create a prosperous community; how can I best organize and fund economic development activities in my community?” The short answer was, “It depends on the situation”—a trite but true response because every community is unique. Here are some guidelines to help answer this question:

• Economic development activities should be tailored to the specific needs of a community. A mountain town away from a major highway with a tourism-based economy might want to emphasize small business development oriented toward the hospitality and retail sectors rather than business recruitment. However, promoting the community as a great location for small technology-based professional firms that can deliver their services remotely, or something similar, might be a good strategy for economic diversification. Contrastingly, a larger town with good highway and rail service and lots of developable land might want to concentrate its economic development efforts on recruiting advanced manufacturing companies or distribution centers.

• The organization and funding of economic development activities depend on the political landscape of a community. There are almost as many models for structuring and delivering economic development activities or services as there are individual communities. These models range from mainly public sector delivery and funding to mainly private sector delivery and funding and variations in between:

• Public Sector Model: Economic development activities publicly funded, usually within an office of economic development in county or city government.

• Private Sector Model: Economic development activities within a private nonprofit organization.

• Public/Private Model: Economic development activities within a private nonprofit organization jointly supported and funded by the public and private sectors.

A community’s political situation often influences the type of economic development model chosen. For example, in communities without a strong history of cooperation among local governments, it can be more difficult to form a jointly funded public/private partnership.

In communities that can support them, public/private models can offer significant advantages. Typically, they are structured as private, nonprofit organizations with funding from both local governments and private sector contributions or membership dues. The boards of directors of these organizations include representatives from local governments, key community organizations, and the business sector. They often are Internal Revenue Service certified 501(c)(3) charitable organizations supporting tax-deductible contributions or 501(c) (6) membership organizations eligible to receive proceeds from certain local taxes.

Partnerships between the public sector and private sector for economic development can offer numerous advantages. Sometimes public funding and support for economic development can suddenly change when a new administration comes into office. Public/private organizations with diversified funding can provide more continuity and consistency to economic development activities. In addition, public/private economic development organizations with broad-based board representation can serve as a platform for increased cooperation, communication, and trust among local governments and private sector businesses and organizations. This can significantly improve the community development process, helping the community reach a consensus on a number of issues and create a unified vision for the future.

A growing trend in economic development is regional partnerships among cities and counties. Local economies are naturally regional—workers commuting over city and county lines, businesses buying inputs and services from and selling to other businesses in a region, and consumers patronizing retail shops and restaurants within a region. In addition, greater marketing reach can be obtained by combining the resources of multiple cities and counties in a region. For example, while an economic development organization for an individual county might not have a sufficient budget to attend a national or international industry trade show, a regional economic development marketing organization could represent all of the economic development organizations in a region. If, as a result, a new company moves into the region, all cities and counties are likely to benefit as workers and shoppers travel within the region. For example, the Upstate South Carolina Alliance (Figure 4.5) represents the cities and counties in the Greenville/Spartanburg combined metro area. The Alliance markets the multi county area as a place where companies can choose to locate in an urban, suburban, or rural location, and still enjoy the benefits of the entire upstate area including its labor force and transportation infrastructure.

Figure 4.5 Upstate South Carolina Alliance

Source: www.upstatescalliance.com/site-selection/map-center/

Bringing It All Together: Community Economic Development and Prosperity

Throughout the book we have defined community development and economic development as processes and outcomes. Chapter 3 showed how the process of community development, including creating a vision and addressing community issues through an inclusive strategy, paves the way to the outcome of a prosperous-ready community. This chapter described how the process of economic development builds on that foundation, increasing the flow of money into the community and creating new jobs and higher incomes leading to an economically prosperous community. Chapter 2 provided the groundwork for all of this by offering a new, more comprehensive definition of community prosperity composed of four components: basic needs, quality of life, social needs, and the economy. Using the roadmap to prosperity as an illustration, Chapter 2 showed that the four components are highly interrelated, with a strong local economy providing a foundation for the other three components.

These links are shown in Figure 4.6: The Community Economic Development Prosperity Chain. The process works as follows:

Figure 4.6 The community and economic development prosperity chain

• The chain begins with a community vision. Just as a vision or mission statement for a company or organization helps guide its actions and policies, a vision for a community helps unite residents behind common goals.

• The vision helps guide the community development process, leading to the outcome of a prosperous-ready community attractive to businesses and residents. A prosperous-ready community also provides three of the prosperous community components: basic needs, quality-of-life enhancements, and social needs. These then feed through the flow to the outcome of community prosperity.

• The community vision also helps guide the economic development process, including its funding, organizational structure, and programs.

• Finally, the outcome of community development (a prosperous-ready community) and the economic development process combine to produce a prosperous economy and finally our end goal: a balanced, prosperous community.

Figure 4.6 illustrates a key point of the book that is worth repeating: economic development success and prosperity depend heavily on building a prosperous-ready community through the community development process. Unfortunately, many communities miss or ignore this point and handicap their ability to achieve success. As discussed in this chapter, a community with a good workforce, infrastructure, and other factors that businesses look for and that offers a good quality of life that residents want is primed for success. “Fatal flaws,” such as limited water and sewer service or a poor school system, can greatly handicap economic development efforts and community prosperity. No community is perfect, and all communities have relative strengths and weaknesses. Targeting economic development efforts with this in mind is a smart policy.

In theory and practice, community development and economic development are inextricably linked, and many experts and practitioners in the field prefer a more encompassing term. The authors of one article use the term “community economic development” which has “a broader dimension that includes public capital, technology and innovation, society and culture, institutions, and the decision making capacity of the community.”14 Does it sound familiar? As we advocate in the book, community economic development is the key to building prosperous communities.

Prosperous Community Toolbox

Read, Reflect, Share, and Act

The theme of Chapter 4 is building on the foundation of a prosperous-ready community with the economic development process to achieve the outcome of a prosperous community. It starts with a simple model of how money flows into and out of your community to create wealth. However, true community prosperity goes much deeper—it also involves defining economic development for your community and proactive marketing to achieve your vision of prosperity. The Chapter 4 tools are intended to help you assess how your community has grown and changed in recent years; it’s competitive advantages; your community’s economic development process; and collaboration with surrounding communities for regional economic development programs and opportunities.

4.1 Assess the growth and change that has occurred in your community over the past 5 to 10 years. Using the boxes “How Does Your Local Economy Measure Up?” from Chapter 2 and “Is It Economic Development or Just Growth?” from this chapter as guides, decide whether your community has experienced economic development or just growth. Are income levels in your community increasing? Is your workforce becoming more skilled? Is recent growth consistent with your community’s vision for the future? Use the results of this assessment as a call to action and, if necessary, a course correction in your community’s roadmap to prosperity.

4.2 Assess your community as a competitive location for businesses and other job-generating organizations. Through focus groups, individual interviews, and surveys, obtain broad input from existing businesses and organizations on the strengths and weaknesses of your community as a business location. Statistical benchmarking of your community to others in terms of wage rates, cost of living, and other key locational factors is also extremely useful. Some communities engage consultants to help them with this process and compare them to other communities. An outside, objective viewpoint is often the best way to evaluate your community. Develop plans to address the weaknesses and build on the strengths.

4.3. Evaluate the economic development process in your community. What organizations in your community directly deliver economic development services or are otherwise involved? Understand how these organizations are funded and staffed. Are they delivering the kinds of economic development services such as marketing, business recruitment, business retention, and new business startup assistance discussed in this chapter as appropriate for your community? Compare the economic development process in your community with other communities. State departments of economic development or outside consultants can assist in this comparison.

4.4 Determine the status and/or potential for regional economic development programs and activities. Does your community currently cooperate with surrounding communities or counties to promote your region to companies, tourists, or other appropriate target markets? How successful have those efforts been and how can your community promote more regional cooperation for economic development?

Visit www.prosperousplaces.org/rebooteconomics_toolbox/ to download templates and resources for the Chapter 4 tools.

If you skipped the chapter and came directly here to see what Osceola, Arkansas did to reboot its economy, we understand. We invite you now to read the chapter to see the bigger picture and overall process they followed. To those of you who have read the chapter, congratulations; the rest of the story will be more meaningful.

Osceola, Arkansas—The Rest of the Story

Let’s review the question posed at the beginning of the chapter: how did Osceola, Arkansas (Figure 4.7) reboot itself from “almost the point of no return” to a healthy community with thousands of new jobs and billions of dollars in new corporate investment? The answer in a nutshell: by understanding and following the principles of good community and economic development as described in the book. Osceola is an excellent example of how to lay a foundation for success with community development and then build on it with economic development.

The first step in Osceola’s recovery was to create a more prosperous-ready community attractive to businesses. With Osceola’s troubled public schools, local businesses were having difficulty finding labor with the necessary skill sets, so they began to work with the city administration to find a solution. The community decided to ask the state for permission to establish a charter school that could produce educated students with good work skills. After several community meetings and differences of opinion, the community united behind the effort and opened a charter school.

Encouraged by their success with the charter school, Osceola reached out to the Arkansas Economic Development Commission and statewide utilities and told them it wanted to pursue new business investment aggressively and was willing to invest public money into the right projects. Through these outreach contacts, Osceola discovered that Denso, a Japanese-owned auto parts company, was looking for a manufacturing site in the southern states. City representatives showed Denso the charter school and explained how the community had come together to address its education and labor problem. Denso decided to locate the plant in Osceola, creating 400 jobs. While Denso executives cited the improved labor force as a reason for selecting Osceola, they also were impressed with how the community came together and solved one of its biggest problems. An executive from Denso was quoted in The Wall Street Journal as saying, “It was their aggressiveness that really impressed us.”

Despite Osceola’s educational reform and workforce improvement, Denso initially still had questions about Osceola’s commitment to continuous improvement in the schools when making the location decision. On this concern, the Denso executive was quoted as saying, “Is there a future here? Are they doing things that are going to drive them forward? Do they have that commitment to do it? We saw that continuously in Osceola.” Denso decided to locate in Osceola not only because of the city’s past achievements, but also because they were convinced the city would continue to practice good community development principles and move forward. Osceola’s success story was featured on the front page of the national edition of The Wall Street Journal in 2006.

The story continues after the Denso win. Voters in the city passed a one-half cent sales tax to provide continuing support for economic development activities, including workforce training and incentives. Some of the sales tax money was earmarked to help support the newly formed Great River Economic Development Foundation, a public-private partnership among Mississippi County, Osceola, and Blytheville, the county’s largest town. Building on an emerging cluster of metals product companies already in the area, the Foundation, county, and the cities together were able to attract new companies to the area including the previously mentioned Big River Steel Company with its initial investment of $1.3 billion.

Over the past 20 years, according to the Great River Economic Development Foundation, 4,100 new jobs have been created in Mississippi County, along with private capital investment of approximately $4 billion. The annual payroll from these new jobs is approximately $130 million. The total economic impact of the new jobs, payrolls, and investment is even larger than these numbers when the multiplier or re-spending effect is taken into account. Total public investment in these projects over 20 years through grants, worker training, and other incentives has been approximately $42 million, a sound return by most any measure (recall our discussion that community enterprise is a term that can apply broadly to economic development, even if the investment came from the private sector). The story of Osceola, Blytheville, and Mississippi County is an encouraging example of good teamwork, and illustrates several key factors leading to economic development success that we have discussed in this chapter:

• Community development lays the foundation for economic development. What originally attracted Denso was Osceola’s proven success in turning one of its biggest liabilities, education, into one of its biggest strengths. Along with Osceola’s commitment of continuing support, that success convinced Denso that the city could accommodate its future needs.

• Osceola had a proactive approach to economic development and stepped up its commitment to recruit new industries and spread the word.

• Cooperation among local governments with more resources in the same county and beyond (regional partnerships) can facilitate greater economic development success.

• Understanding and marketing on local strengths, in this case, an emerging cluster of metals companies in the area, can contribute to economic development success. This is one way the “target industry” approach can make economic development programs more effective and efficient.

• Community and economic development efforts should be ongoing, not just one-time events. Countywide public and private efforts spearheaded by the Great River Economic Development Foundation continued after the Denso success. Together, Osceola and Mississippi County were able to recover from the economic shock of the Fruit of the Loom plant closing and, later, the gradual reduction in employment of another larger company in town, American Greetings.

1 Local government spending can, however, have a net positive effect on the local economy in at least two ways. First, local governments may purchase fewer outside and more local goods and services than residents would have with the money paid in taxes. Second, some of the money paid in taxes would likely have been put in savings by local residents, and the local government “saving rate” may be lower (and therefore the consumption rate higher) than that of the taxpayers.

2 H. Galloway. “Understanding Local Economies.” in R. Phillips, and R.H. Pittman. 2015. An Introduction To Community Development, New York, N.Y: Routledge.

3 2021. Montpelier-Vt.Org, www.montpelier-vt.org/DocumentCenter/View/1223/Economics-and-Livelihoods-PDF

4 2021. Hsvchamber.Org, http://hsvchamber.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/redstone_economic_impact_analysis_may.pdf

5 Statista. 2021. United States——Ratio of government expenditure to gross domestic product (GDP) 2026 | Statista, [online] Available at: <www.statista.com/statistics/268356/ratio-of-government-expenditure-to-gross-domestic-product-gdp-in-the-united-states/> (accessed June 07, 2021).

6 American Economic Development Council. 1984. “Economic Development Today: A Report to the Profession,” Schiller Park, Illinois.

7 G. Sahota. 2021. Economic Development Basics | CALED, [online] CALED, Available at: https://caled.org/economic-development-basics/ (accessed June 07, 2021).

8 Encyclopedia Britannica. 2021. Economic development, [online] Available at: <www.britannica.com/topic/economic-development> (accessed June 07, 2021).

9 R. Starner. 2021. Site Selectors Survey: More Than Some Like It Hot | Site Selection Magazine, [online] Site Selection, Available at: https://siteselection.com/issues/2018/jan/site-selectors-survey-more-than-some-like-it-hot.cfm (accessed June 07, 2021).

10 S. Cao. 2021. Why Elon Musk And Other Tech Billionaires Are Leaving Silicon Valley For Texas, [online] Observer, Available at: https://observer.com/2020/12/elon-musk-tech-leaving-silicon-valley-for-texas-billionaires/#:~:text=At%20an%20event%20last%20week,it%20was%20not%20unexpected%20news. (accessed June 07, 2021).

11 R. Pittman and T. Roberts. “Retaining and Expanding Existing Community Businesses.” in R. Phillips, and R.H. Pittman. 2015. ” An Introduction To Community Development, New York, N.Y: Routledge.

12 J. Gruidl and D. Markley. “Entrepreneurship as a Community Development Strategy.” in R. Phillips, and R.H. Pittman. 2015. An Introduction To Community Development, New York, N.Y: Routledge.

13 “Blue Ridge Food Ventures—The Place Where Tasty Things Happen,” 2021. Blueridgefoodventures.Org, https://blueridgefoodventures.org

14 R. Shaffer, S. Deller, and D. Marcouiller. 2006. “Rethinking Community Economic Development,” Economic Development Quarterly 20, No. 1, p. 64.