Creating value for the customer |

INTRODUCTION

The widespread adoption of the marketing concept by organisations is a relatively recent event. With one or two exceptions marketing literature is barely fifty years old. But during those fifty years the way we think about marketing and the way it is practised has changed significantly. Marketing has progressed from a simplistic focus on ‘giving the customers what they want’ to a pan-company orientation in which the specific capabilities of the business are focused around creating and delivering customer value to targeted market segments.

Philip Kotler, who has probably done more than any writer in the past fifty years to articulate the changes in marketing thinking, captured the essence of conventional marketing in the first edition of his groundbreaking book Marketing Management1in 1967:

![]() Marketing is the analysing, organising, planning and controlling of the firm's customer-impinging resources, policies, and activities with a view to satisfying the needs and wants of chosen customer groups at a profit.

Marketing is the analysing, organising, planning and controlling of the firm's customer-impinging resources, policies, and activities with a view to satisfying the needs and wants of chosen customer groups at a profit.

In the growth markets of the 1960s and 1970s, the marketers’ challenge was to capture as much of that growth in demand as early as possible. This led them to focus on volume and market share, or what we would now term a ‘transactional’ approach to marketing. As many markets matured in the closing decades of the twentieth century, the emphasis gradually switched from the corporate objective of maximising market share towards a concern with the ‘quality of share’ in recognition of the fact that not all customers are equally profitable. This has led to the notion that the purpose of marketing is to create profitable and enduring relationships with selected customers. A key role of marketing in this new framework is to determine what value propositions to create and deliver to which customers.

Today's marketing-oriented companies are actually ‘market driven’, in the sense that they are structured, organised and managed with the sole purpose of creating and delivering value to chosen markets. Ideas and phrases such as customer intimacy, customer-centric and customer focus summarise the new concept of the corporation as an entity that exists to deliver value to carefully selected market segments. This is not some altruistic or idealistic view of the firm as the provider of customer satisfaction at any cost. Rather it is a hard-edged business model that recognises that long-term profits are more likely to be maximised through satisfied customers who keep returning to spend more money.

This is the backdrop against which the recently emerged paradigm of ‘relationship marketing’ should be viewed.

The evolution of relationship marketing

Marketing literature provides a useful guide to the way marketing theory and practice have developed. In the 1950s frameworks were formulated to manipulate and exploit market demand. The most enduring of these was the idea of the ‘marketing mix’, particularly as enshrined in the shorthand of the ‘4Ps’ of product, price, promotion and place. These were the levers that, if pulled appropriately, would lead to increased demand for the company's offer. Marketing management aimed to devise strategies that would optimise expenditure on the marketing mix to maximise sales.2

The fundamental concept of the marketing mix still applies today in the sense that organisations need to understand and manage the influences on demand. Yet we need to remember that these original frameworks for marketing action were devised in a unique environment. They emerged from the United States during a period of unprecedented growth and prosperity, and focused on fast-moving consumer goods.

But though the tools and techniques developed in a particular era and for particular products might not necessarily be successfully applied more universally, the basic ideas of ‘4Ps marketing’ were rapidly extended into industrial markets,3 then service markets4 and even not-for-profit markets.5

During the closing years of the twentieth century some of these basic tenets of marketing were increasingly being questioned. The marketplace was vastly different from that of the 1950s. In many instances consumers and customers were more sophisticated and less responsive to the traditional marketing pressures – particularly advertising. There was greater choice, partly as a result of the globalisation of markets and new sources of competition. And many markets had matured, in the sense that growth was low or non-existent.

As a result of these and many other pressures, brand loyalty is weaker than it used to be6 and simplistic 4Ps marketing is unlikely to win or retain customers either in consumer or industrial markets. The efficacy of conventional marketing has been repeatedly challenged in articles and conference papers along the lines of ‘Is marketing dead?’7, 8

It is against this background that the new wave of marketing thinking has become apparent, and the label ‘relationship marketing’ applied to describe the revised framework or paradigm.9

In the earlier edition of this book,10 we developed a general model of relationship marketing. We have since refined it, but it still embodies the following elements. Relationship marketing:

![]() emphasises a relationship, rather than a transactional, approach to marketing;

emphasises a relationship, rather than a transactional, approach to marketing;

![]() understands the economics of customer retention and thus ensures the right amount of money and other resources are appropriately allocated between the two tasks of retaining and attracting customers;

understands the economics of customer retention and thus ensures the right amount of money and other resources are appropriately allocated between the two tasks of retaining and attracting customers;

![]() highlights the critical role of internal marketing in achieving external marketing success;

highlights the critical role of internal marketing in achieving external marketing success;

![]() extends the principles of relationship marketing to a range of diverse market domains, not just customer markets;

extends the principles of relationship marketing to a range of diverse market domains, not just customer markets;

![]() recognises that quality, customer service and marketing need to be much more closely integrated;

recognises that quality, customer service and marketing need to be much more closely integrated;

![]() illustrates how the traditional marketing mix concept of the 4Ps does not adequately capture all the key elements which must be addressed in building and sustaining relationships with markets;

illustrates how the traditional marketing mix concept of the 4Ps does not adequately capture all the key elements which must be addressed in building and sustaining relationships with markets;

![]() ensures that marketing is considered in a cross-functional context.

ensures that marketing is considered in a cross-functional context.

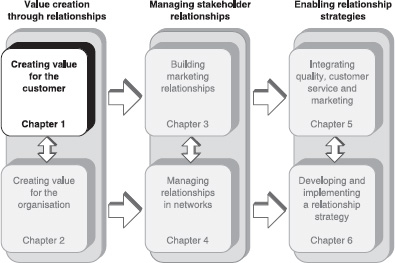

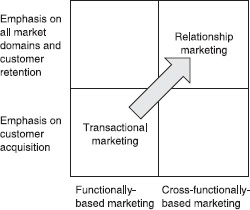

This broader concept of relationship marketing is depicted in Figure 1.1.

FIGURE 1.1 The transition to relationship marketing

The fundamental principles of relationship marketing

As Figure 1.1 suggests, a number of characteristics distinguish relationship marketing from earlier frameworks. The first is an emphasis on extending the ‘lifetime value’ of customers through strategies that focus on retaining targeted customers. The second is the recognition that companies need to forge relationships with a number of market domains or ‘stakeholders’ if they are to achieve long-term success in the final marketplace. And the third is that marketing has moved from being the sole responsibility of the marketing department to become ‘pan-company’ and cross-functional.

Maximising the lifetime value of a customer is a fundamental goal of relationship marketing.

Maximising the lifetime value of a customer is a fundamental goal of relationship marketing. In this context, we define the lifetime value of a customer as the future flow of net profit, discounted back to the present, that can be attributed to a specific customer. Adopting the principle of maximising customer lifetime value forces the organisation to recognise that not all customers are equally profitable and that it must devise strategies to enhance the profitability of those customers it seeks to target. We go on to explore these ideas in more depth in Chapter 2. But, in essence, companies need to tailor and customise their relationship marketing strategies even to the extent of so called ‘one-to-one’ marketing.11

The second differentiating feature of relationship marketing is the concept of focusing marketing action on multiple markets. Conventionally, marketing strategy has been structured solely around the customer. Of course, the ultimate aim of relationship marketing strategies is to compete successfully for profitable customers. But to do this firms need to define more broadly the markets that need to be addressed. Relationship marketing recognises that multiple market domains can directly or indirectly affect a business's ability to win or retain profitable customers. These other markets include suppliers, employees, influencers, distributors and alliance partners. We have previously defined10 this multiple market focus as the ‘six markets model’. But there is nothing sacrosanct about the number six, and in any given circumstance firms may need to encompass fewer or more ‘stakeholders’ within their overall relationship marketing strategies. We explore the concept of the multiple market model in greater detail in Chapter 3.

The third key element of relationship marketing is that it must be cross-functional.

David Packard, a co-founder of Hewlett-Packard, is reported to have said that ‘marketing is too important to be left to the marketing department’. You could interpret this in a number of ways (for example, the marketing department is not up to the task!) but we choose to understand it as a call to bring marketing out of its functional silo and inculcate the concept and the philosophy of marketing across the business.

In practice this needs to be accompanied by an organisational change that fosters cross-functional working and develops the mindset that everyone within the business serves a customer, be they internal or external customers.

In addition to these three key differentiators, the new paradigm of relationship marketing has a number of other characteristics that distinguish it from conventional marketing. For many years market share was the overriding goal of many organisations, which often followed the precepts particularly associated with the Boston Consulting Group.12 The market share model held that growing market share relative to the competition enabled a company to move down ‘the experience curve’ more quickly, resulting in lower costs and greater profits. But while winning market share early in a growth market can indeed lead to long-term profitability, when markets mature and the growth rate declines, the cost of winning extra percentage points of market share can be prohibitive. This is the reason why many companies, such as Vodafone, have switched their strategic focus from volume towards establishing longer-term relationships with fewer but more profitable customers (see Case Study below). Such companies now talk about ‘share of wallet’ as much as they do about absolute market share.

CASE STUDY Retention – Vodafone rethinks loyalty policy

Cell phone operator Vodafone UK is refocusing its business on customer retention, a move that, on paper at least, confirms a shift in thinking for a major European company.

The dramatic changes at Vodafone will focus on encouraging its distribution channel to provide long-term customers, rather than users enticed merely by introductory offers and associated ‘freebies’. This means the distribution channel will get reduced bonuses and subsidies for winning ‘Pay as you Talk’ and prepaid customers, and that ‘All in One’ mobile phone packages will be scrapped altogether. The reduction in bonuses will effectively bump up the high street starting price of a Pay as you Talk package to around £70, although Vodafone says that the distributors will ultimately set prices.

Peter Bamford, chief executive of the UK, Middle East and Africa region, explains: ‘These changes in Vodafone UK's commercial policies reflect the move of the UK market into a phase of greater maturity and our recognition of the need to reduce the current levels of expenditure on customer acquisition. We aim to reward our distribution channel for quality customers, rather than the quantity of customers, thereby ensuring the increasing focus on customer retention and development across the business.’

The moves come as a result of Vodafone chiefs studying the effects of active and non-active (not using the phone for more than three months) customers and concluding that a greater number of non-active customers come from the non-subscription band. Consequently Vodafone intends to prise more funds from each customer and push customers towards contracts. Chris Gent, Vodafone Group chief executive, described the change in priority as being towards ‘margin improvement and cash flow rather than growth and market share’.

Based on: Customer Relationship Management magazine (2001), Southampton: Wilson Publications.

Underpinning this idea of an ongoing relationship with individual customers is a greater emphasis on service and on tailoring the offer to meet their precise needs. The concept of customer service is wide-ranging and relates to the totality of encounters between suppliers and buyers. It extends from the pre-purchase stage of customer engagement, through to the transfer of the offer from the supplier to the customer, and continues through the life cycle of usage.

A prime objective of any customer service strategy should be to enhance customer retention. While customer service obviously plays a role in winning new customers, it is perhaps the most potent weapon in the marketing armoury for retaining customers. Researchers at management consultants Bain & Co have found that retained customers are more profitable then new customers for the following reasons:

![]() the cost of acquiring new customers can be substantial. A higher retention rate implies that fewer customers need be acquired more cheaply;

the cost of acquiring new customers can be substantial. A higher retention rate implies that fewer customers need be acquired more cheaply;

![]() established customers tend to buy more;

established customers tend to buy more;

![]() regular customers place frequent, consistent orders and, therefore, usually cost less to serve;

regular customers place frequent, consistent orders and, therefore, usually cost less to serve;

![]() satisfied customers often refer new customers to the supplier at virtually no cost;

satisfied customers often refer new customers to the supplier at virtually no cost;

![]() satisfied customers are often willing to pay premium prices for a supplier they know and trust;

satisfied customers are often willing to pay premium prices for a supplier they know and trust;

![]() retaining customers makes market entry or share gain difficult for competitors.

retaining customers makes market entry or share gain difficult for competitors.

Customer service is critically important in cementing relationships.

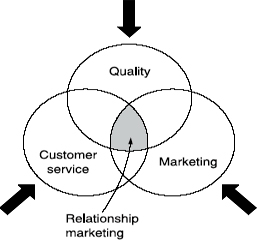

Customer service is critically important in cementing relationships. Marketing is concerned with ‘exchange relationships’ between the organisation and its customers, and quality and customer service are key linkages in these relationships. At its simplest, the exchange relationship is the customer paying for the benefits they receive. But the relationship marketing view is that the customer gives loyalty in exchange for their expectation that value will flow to them from the relationship. This flow of value includes not just product benefits but a number of less tangible benefits relating to the quality of the experience within a wider customer service context. So the challenge to the organisation is to align marketing, quality and customer service strategies more closely. In the past organisations have tended to treat these as separate and unrelated. Consequently, decisions affecting customer service may have been taken by diverse functions such as distribution, manufacturing or sales. Likewise, quality was seen as the preserve of a specific quality control or assurance function. Under the relationship marketing paradigm these three areas are merged and given a sharper focus (Figure 1.2).

FIGURE 1.2 The relationship marketing orientation: bringing together customer service, quality and marketing

The expanded marketing mix

Traditionally, marketing has been seen as the process of perceiving, understanding and stimulating the needs of specially selected target markets, and channelling resources to satisfy those needs. Marketing is concerned with the dynamic relationships between a company's products and services, the customer's wants and needs and the activities of the competition.

Conventional marketing proposes that a company manages and coordinates a number of critical elements – commonly known as ‘the marketing mix’ – in order to achieve its objectives.

Marketing mix is the term traditionally used to describe the important ingredients of a marketing programme. The origins of the concept lie in work done by Borden at the Harvard Business School in the early 1960s.13 He suggested that companies should consider twelve elements when formulating a marketing programme, namely:

![]() product planning

product planning

![]() pricing

pricing

![]() branding

branding

![]() channels of distribution

channels of distribution

![]() personal selling

personal selling

![]() advertising

advertising

![]() promotions

promotions

![]() packaging

packaging

![]() display

display

![]() servicing

servicing

![]() physical handling

physical handling

![]() fact finding and analysis

fact finding and analysis

The marketing mix concept has become widely accepted, particularly since Borden's rather long list was condensed and simplified into a much shorter one, usually known as the ‘4Ps’. These four categories have now been enshrined in marketing theory and practice.

The 4Ps comprise:

| Product | the product or service being offered. | |

| Price | the price charged and the terms associated with the sale. | |

| Promotion | advertising, promotional and communication activities. | |

| Place | the distribution and logistics processes involved in fulfilling demand. |

Each of the 4Ps is, of course, a collection of sub-activities (for example, promotion includes both advertising and personal selling). Even so, the 4Ps’ model tends to oversimplify the complex process of winning and keeping customers, particularly in today's more complex and fast-moving climate, as we suggested earlier. This has led to suggestions that we need an expanded marketing mix.

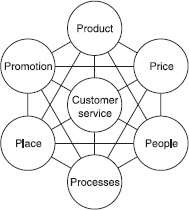

This expanded marketing mix, as outlined in Figure 1.3, comprises seven broad elements – the traditional 4Ps of product, price,promotion, and place plus three additional elements of people, processes and customer service.

FIGURE 1.3 The expanded marketing mix

We alluded earlier to the central importance of customer service in relationship marketing, and will discuss it in greater detail in Chapter 5. But the two additional elements of ‘people’ and ‘processes’ have a critical role to play in this expanded marketing mix.

People

Most companies acknowledge the importance of their people in creating a successful business, but only a few go beyond lip-service. There is a strong argument for human resource management and marketing management to be much more closely integrated. In Chapter 3 we examine the vital stakeholder domain of ‘internal markets’ more closely. But it is worth exploring briefly here some of the key connections between the ‘people’ element of the expanded marketing mix and the creation of enduring relationships with customers.

We hear a lot these days about ‘corporate culture’ and ‘shared values’. Essentially these ideas reflect the fact that organisations where everyone is pursuing the same goals are likely to be the most successful. The evidence points to a relationship between the way employees and managers feel about their company, the values they share, their job satisfaction and their approach to customer service. In short, satisfied employees make for satisfied customers.

Because employees are a key element in an organisation's success, some companies have introduced formal mechanisms to include them in their overall marketing strategy. These mechanisms are broadly described as ‘internal marketing’. Internal marketing can be defined as the creation, development and maintenance of an internal service culture and orientation that will help the organisation achieve its goals.14 The internal service culture directly affects just how service-and customer-oriented employees are. Developing and maintaining a customer-oriented culture is a critical determinant of long-term success in relationship marketing. It is an organisation's culture – its deep-seated, unwritten system of shared values and norms – that has the greatest impact on employees, their behaviour and attitudes. The culture of an organisation in turn dictates its ‘climate’ – the policies and practices that characterise it and reflect its cultural beliefs.

The structure of the organisation can prevent internal marketing strategies being effectively deployed. Classic, conventional organisations are built around ‘vertical’ departments that often become functional ‘silos’.

If employees are to become more connected to the market, the organisations themselves need to become ‘customer-centric’. In other words, they need to shed hierarchical, inward-facing structures in favour of cross-functional, team-based approaches and much greater integration between ‘front-office’ and ‘back-office’ activities.

Process

Processes are the ways in which firms create value for their customers.

One of the biggest changes in the way in which we think about organisations has been our new understanding of the importance of ‘processes’. Processes are the ways in which firms create value for their customers. They are fundamental and largely generic across the spectrum of businesses. Davenport15 defines a process as:

![]() a specific ordering of work activities across time and place, with a beginning, an end, and clearly identified inputs and outputs: a structure for action.

a specific ordering of work activities across time and place, with a beginning, an end, and clearly identified inputs and outputs: a structure for action.

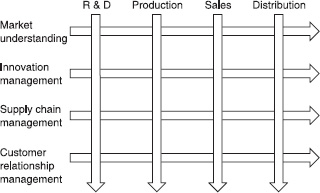

Processes are ‘horizontal’, in that they cut across traditional ‘vertical’ functions (see Figure 1.4). They are inter-disciplinary and cross-functional.

The following ‘high-level’ business processes are critical:

![]() the market understanding process;

the market understanding process;

![]() the innovation management process;

the innovation management process;

![]() the supply chain management process;

the supply chain management process;

![]() the customer relationship management process.

the customer relationship management process.

Within these generic processes there are ‘sub-processes’ that also need to be managed across functions.

We will examine each of these key business processes in turn.

FIGURE 1.4 Processes cut across conventional functions

The market understanding process

Successful marketing strategies are built around a deep understanding of the marketplace. In particular, the motivations of buyers and the things they value must be the building blocks of any marketing strategy. Being in close touch with customers is a prerequisite in fast-changing markets. It is not only the marketing department's responsibility to have this ongoing dialogue with customers; all parts of the business have to be informed by customers. It is just as critical for production management and procurement, for example, to be closely connected to needs of customers as it is for, say, marketing or sales people.

Being customer focused has always been, and always will be, a fundamental foundation of a market-oriented business, but it is no longer enough to identify customer needs purely through market research. Companies today need to be ‘ideas driven’ and ‘customer informed’. In other words, they need to extend and leverage their knowledge in ways that create value for customers. In today's marketplace knowledge management is a critical component of market understanding. Successful companies are utilising superior knowledge proactively to create products and services rather than reacting to emerging market trends.

Ideas and knowledge are ubiquitous – they exist across the business and beyond it. Consequently, the business needs processes in place to capture ideas and knowledge and convert them into marketing opportunities. In a sense, the market understanding process underpins all the other business processes.

The innovation process

Every business faces the continuing challenge of maintaining a flow of successful new product/service introductions into the marketplace. As life cycles become ever shorter and demand more volatile, being able to respond to changes in customer requirements and to exploit new technology-based opportunities has become a key competitive capability.

Again, innovation has to be managed cross-functionally. It cannot be the sole preserve of any one particular department. Those companies that have adopted a cross-functional approach to innovation management have found it has paid significant dividends. Typically, such companies have formed inter-disciplinary teams that bring together a multitude of skills and knowledge bases. These teams are self-managed and autonomous, able to take decisions and to short-circuit the conventional and time-consuming procedures for taking new products to market.

Such teams benefit from the interplay of ideas from different disciplines and, by performing activities concurrently or in parallel, they can condense the time it takes to move an idea from the drawing board into the marketplace. In the car industry such teams are now the norm for new product development. Indeed, not only do these teams draw their membership from different functions across the business, they often exploit further opportunities for innovative thinking by including representatives from suppliers too.

The supply chain process

Once demand has been generated, how will it be fulfilled? This is the role of the demand chain process. In the past, fulfilling orders was not regarded as being strategically significant. While it was a necessary activity it was a cost, and therefore something to be managed as efficiently as possible. Today the emphasis has shifted. The way that a business satisfies demand and services its customers has become a fundamental basis for successful and enduring relationships.

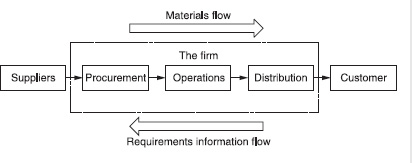

This process is commonly termed the ‘supply chain’, but the label ‘demand chain’ more accurately describes its central role in satisfying demand. Whatever the terminology, the important principle is that it should be managed as a horizontal business process that connects customers with the organisation and extends upstream into the supplier base. Ideally, we should aim to manage the business as an ‘extended enterprise’ from the customer's customer back through the internal operations of the firm to the supplier's supplier. Figure 1.5 depicts this notion of an integrated supply chain.

The purpose of managing the supply chain as an integrated process is to enable the organisation to become more ‘agile’ in its response to demand. Agility is an increasingly important competitive capability.16 As demand becomes more volatile and less predictable the ability to move quickly, to change direction and to meet changed requirements in shorter time-frames is critical. Agility is not a single company concept; it requires the closest connections upstream and downstream, particularly through sharing information on demand. A demand chain is, in effect, an ‘information highway’ where all the partners in the chain have access to the same information.

FIGURE 1.5 The supply chain

In a sense, these three critical business processes are all subsidiary to, and form the basis of, the fourth key process – the customer relationship management process.

The customer relationship management process

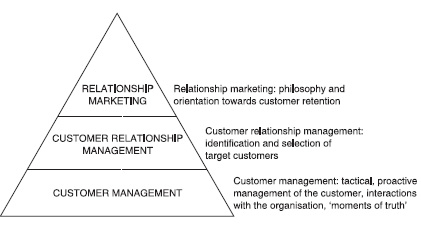

In a way, the whole of this book is devoted to developing an understanding of the customer relationship management (CRM) process. We define CRM as follows:-

![]() CRM is a strategic approach to improving shareholder value through the development of appropriate relationships with key customers and customer segments. CRM unites the potential of IT and relationship marketing strategies to deliver profitable, long-term relationships. Importantly, CRM provides enhanced opportunities to use data and information both to understand customers and implement relationship marketing strategies better. This requires a cross-functional integration of people, operations and marketing capabilities enabled through information technology and applications.

CRM is a strategic approach to improving shareholder value through the development of appropriate relationships with key customers and customer segments. CRM unites the potential of IT and relationship marketing strategies to deliver profitable, long-term relationships. Importantly, CRM provides enhanced opportunities to use data and information both to understand customers and implement relationship marketing strategies better. This requires a cross-functional integration of people, operations and marketing capabilities enabled through information technology and applications.

Customer relationship management, we suggest, builds on the philosophy of relationship marketing by utilising information technology to enable a much closer ‘fit’ to be achieved between the needs and characteristics of the customer and the organisation's ‘offer’. Figure 1.6 highlights the connection between relationship marketing, CRM and the more tactical management of specific customer relationships.

CRM allows a business to target customers more closely and implement ‘one-to-one’ marketing strategies where appropriate. As a concept and a set of tools it is equally appropriate for business-to-business (b2b) or business-to-consumer (b2c) marketing.

Business-to-business marketing – managing relationships with business customers rather than consumers – has attracted much attention over recent years. It has long been acknowledged that marketing to other organisations requires a deep understanding of those customers’ business processes and value-creation processes. For a start, there will typically be a number of people involved in purchase decisions in a business customer. This group is usually referred to as the decision-making unit (DMU). It is conventional17 to classify the members of a DMU as follows:

| Gatekeeper | Not involved in the final decision but can control |

| access and the flow of information to others. | |

| Influencer | May influence the opinions and the decisions of |

| the buyer or decision-maker. | |

| User | End user of the product who generally initiates the |

| request. | |

| Buyer | Identifies possible suppliers, negotiates terms of |

| purchase. | |

| Decision-maker | Has formal or informal power to select suppliers |

| and approve purchase. |

These roles may be separate or they may overlap. But organisations marketing to other organisations clearly need to understand the composition of the specific DMU and the types of issues that concern the various players. In a sense, a prime goal of CRM is to establish appropriate relationships with each of these players.

In b2c marketing, the same principles of understanding the DMU apply. Where there are multiple members of a household – typically families – many purchase decisions involve more than one person. So relationships need to be established at many levels. Marketing to children is a good example, in that the DMU possibly includes gatekeepers, influencers and decision-makers as well as the end user.

One particular b2b relationship management model that has gained widespread acceptance in recent years is the formation of cross-functional teams to manage specific customers. Thus for major accounts a business will often create a multi-disciplinary team that is capable of managing multi-level relationships with the client organisation. In this type of relationship traditional ‘selling’ has been replaced by ‘customer management’.

From transactions to relationships: the role of customer value

Relationship marketing differs from transactional marketing in a number of important ways. These are summarised in the box:

| Transactional marketing | Relationship marketing |

| • Focus on volume | • Focus on profitable retention |

| • Emphasises product features | • Emphasises customer value |

| • Short timescale | • Longer-term timescales |

| • Little emphasis on customer service | • High customer service emphasis |

| • Moderate customer contact | • High customer contact |

| • Primary concern with product quality | • Concern with relationship quality |

As the old model is increasingly viewed as inadequate to cope with today's business environment, marketing is entering a new era. In an environment characterised by global competition, overcapacity and the inevitable trend towards ‘commoditisation’ of markets, the focus has to switch from volume growth to profit growth. The challenge that this changed environment poses to the organisation is to identify how to build enduring relationships with profitable customers.

It is now fairly widely accepted among marketing practitioners and academics that customers base purchasing decisions on the value they perceive they will derive from that purchase. This is not a new idea; in essence it has formed the basis for much economic theory since the time of the early economist Alfred Marshall, if not before.

Customers of every sort, from individual consumers to industrial corporations, seek to acquire value through their purchasing behaviour. Broadly defined, value represents an acceptable ‘solution’ to a buying ‘problem’. In other words, given that buyers are goal oriented – there is a rationale for their purchasing behaviour – they will seek a solution that best achieves that goal.

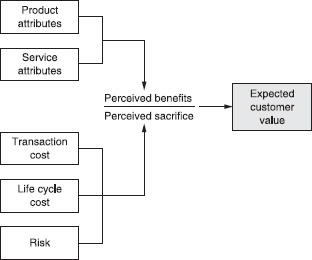

One of the early marketing writers on the subject, Bradley Gale, defined customer value as ‘market-perceived quality adjusted for the relative price of your product’, where market-perceived quality is defined as ‘the customer's opinion of your products (or services) compared to those of your competitors’.18

Gale adopted a concept of quality that is wider than the conventional product-based definition. He believed quality applies to every area that matters to the customer. His model of customer value is shown as Figure 1.7 and it provides a useful starting point for our discussion on the role of customer value.

What is value from a customer perspective? At its simplest, customer value is the relationship between the customer's perception of the benefits they believe they will derive from a purchase compared to the price they will have to pay. However, the definition of ‘price’ needs to be elaborated in this context. Price is not simply the immediate out-of-pocket cost, but also includes all those preliminary and ongoing costs that may be involved – the so-called life-cycle costs – as well as ‘risk’ costs if things go wrong. Equally, the total benefit package includes not just the benefits that flow from the functional attributes of the product, but those that flow from the related service attributes as well.

Figure 1.7 suggests that customer value can be defined as the ratio of perceived benefits to the perceived ‘sacrifice’ that is involved. Clearly the word ‘perceived’ is critical here since both benefits and costs are, to a certain extent, subjective.

FIGURE 1.7 Components of customer value

Source19: From Customer Value Toolkit, 1st Edition,by E. Naumann and R. Kordupleski © 1995. Reprinted with permission of South-Western College Publishing a division of Thomson Learning. Fax 800 730-2215.

This framework could apply equally to consumer and industrial markets since ultimately all purchase behaviour in any context will be influenced by the customer's perception of total costs and benefits.

Customer value is a highly significant component of relationship marketing, as we mentioned earlier. Indeed, we argue throughout this book that relationships are built on the creation and delivery of superior customer value on a sustained basis. This is why a thorough understanding of what constitutes customer value in specific markets and segments is so important.

Relationships are built on the creation and delivery of superior customer value on a sustained basis.

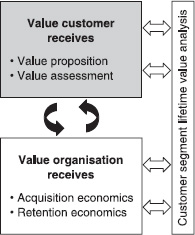

The overall value-creation process can be considered in terms of the three key elements shown in Figure 1.8. These are determining what value the company can provide to its customers (the ‘value customer receives’); determining the value the organisation receives from its customers (the ‘value organisation receives’); and, by managing this value exchange, maximising the lifetime value of desirable customer segments.

FIGURE 1.8 The value-creation process

In this chapter, we consider the first box in Figure 1.8 – the value the customer receives – focusing in particular on developing and assessing a value proposition. Chapter 2 goes on to examine how an organisation can create value for itself by managing both the value it gets from its customers and the value exchange between itself and its customers.

Understanding customer value

Today's successful companies tend to base their marketing strategy around a clearly defined and strongly communicated ‘value proposition’. The value proposition is a summation of all the reasons why a customer should buy the company's product or services. The value proposition, if successful, will also provide the basis for differentiation and the foundation for an ongoing buyer-seller relationship.

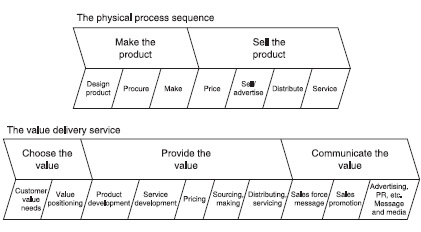

Lanning and Michaels, originally at McKinsey & Co, have developed a framework called the value delivery sequence,20 which reflects the shift from the traditional view of business as a series of functional activities to an externally-oriented view which sees the business as being concerned with value delivery. Figure 1.9 shows the value delivery sequence. This builds on the idea that customers buy promises of satisfaction and they only purchase products because they are of some value to them.

The McKinsey approach argues that focusing on the traditional physical process sequence of ‘make the product and sell the product’ can be ineffecient. The value delivery sequence, by contrast, depicts the business as viewed from the customer's perspective rather than as a series of internally-oriented functions.

The value delivery sequence consists of three key steps: choose the value, provide the value and communicate the value.

![]() Choose the value. Customers typically select products and services because they believe they offer superior value. In this context companies need to understand two things. They need to understand changing customer needs, in terms of the forces driving demand as well as customer economics and the buying process. They also need to understand how well the competition meets those needs, particularly in terms of the products themselves, the service and the price charged.

Choose the value. Customers typically select products and services because they believe they offer superior value. In this context companies need to understand two things. They need to understand changing customer needs, in terms of the forces driving demand as well as customer economics and the buying process. They also need to understand how well the competition meets those needs, particularly in terms of the products themselves, the service and the price charged.

![]() Provide the value. The second stage, providing the value, is concerned with developing a product/service package that creates clear and superior value. This involves focusing on things such as product quality and performance, service cost and responsiveness, manufacturing cost and flexibility, channel structure and performance, and price structure.

Provide the value. The second stage, providing the value, is concerned with developing a product/service package that creates clear and superior value. This involves focusing on things such as product quality and performance, service cost and responsiveness, manufacturing cost and flexibility, channel structure and performance, and price structure.

![]() Communicate the value. This involves the various aspects of promotional activity needed to persuade customers that the values are better than those offered by competitors. It involves organising sales promotion, advertising and the sales force, as well as providing outstanding service in a way that is continually recognised by the target audience.

Communicate the value. This involves the various aspects of promotional activity needed to persuade customers that the values are better than those offered by competitors. It involves organising sales promotion, advertising and the sales force, as well as providing outstanding service in a way that is continually recognised by the target audience.

You can define superior value delivery as providing a product or service that the customer considers gives a net positive value greater than that offered by competitors. So, the current value proposition of Dell Computer Corporation is based on a promise to configure the equipment the way the customer wants and to have it up and running within a matter of days. In this case the value proposition is based not on technology, price or image, but on customisation and service. Similarly, Volvo's value proposition of high levels of safety and reliability at a modest price has resulted in superior perceived value in the eyes of a significant customer segment.

McKinsey suggests that companies wishing to implement a value proposition approach should adopt a three-step sequence:

1 Analyse and segment markets by the values customers desire.

2 Vigorously assess the opportunities in each segment to deliver superior value.

3 Explicitly choose the value proposition that optimises these opportunities.

Lanning and Michaels20 point out that success does not just come down to choosing the right value proposition, but is also based on how thoroughly and innovatively it is delivered and communicated. Creating a strategy and implementation plan that really provides and communicates value is challenging, but it can prove to be a source of differentiation that competitors find very difficult to replicate. The consultants also argue that creating and managing the value delivery sequence helps integrate the different functions within the business and that involving every employee in delivering the chosen value gives added meaning to teamwork.

The ‘one-to-one’ world

For many years a fundamental principle of marketing strategy has been identifying appropriate ‘segments’ around which to focus the firm's offer. In consumer markets these segments may be determined by factors such as age, sex or lifestyle, and in business-to-business markets by industrial sector, size of company and so on.

The concept of segmentation is still valid today, but we are seeing markets fragment into ever smaller segments. It has been suggested that we may have to address ‘segments of one’ in some markets. There are many possible explanations for this trend towards greater fragmentation, but it seems that customers – consumers and organisations – are increasingly seeking specific solutions to their buying ‘problems’. Organisations cannot just offer a choice these days; they have to be able to meet their customers’ precise requirements. Relationships will increasingly be built on the platform of one-to-one marketing,11 where the customer and the supplier in effect create a unique and mutually satisfactory exchange process. The Internet now provides a powerful means of involving customers much more closely in the marketing process through enabling dialogue rather than one-way communication.

Relationships will increasingly be built on the platform of one-to-one marketing.

Companies need to determine the appropriate level of market segmentation ‘granularity’ – that is, macro-segmentation, micro-segmentation or a ‘one-to-one’ approach. The decision will be based on a number of factors, including the existing and potential profitability of different customer types; the available information on customers; and the opportunity to ‘reach’ customers in terms both of communication and physical delivery.

Despite its name, ‘one-to-one’ marketing does not imply adopting a ‘one-to-one’ approach with every single customer. Rather, it suggests understanding customers in terms of their economic importance, and then adjusting the marketing approach to reflect the existing and potential profitability of different customer groups.

Clearly segmenting the customer base and adopting the correct level of segment granularity is an important element of customer strategy.

But to survive in such a one-to-one world, suppliers must have a deep understanding of the requirements of these ever-smaller customer segments – even down to the level of individual customers – and the flexibility to tailor their offer to meet those specific needs.

We will consider each of these challenges in turn.

Customer understanding

Customer understanding needs to go beyond classic market research, which tends to be descriptive and aggregates results together, and drill down at a micro level into the characteristics of the customer/consumer value chain. In other words, we need to understand the processes that customers engage in – running an assembly line, retailing groceries, doing the laundry, cooking meals, and so on – and then recognise the opportunities to create value within those processes. We create value either by making those processes more effective (that is, doing them better) or more efficient (doing them more cheaply).

To help businesses identify such value-creating opportunities, Sandra Vandermerwe21 has developed the concept of mapping what she terms the ‘customer activity cycle’. Essentially the idea is to try to gain a deep understanding of what customers ‘do’ (including activities before and after the ‘doing’) through a detailed mapping of the stages in these customer processes. Once these activity cycles are mapped, the next step is to understand where the opportunities lie to enhance value. Which elements of that activity cycle are the most complex, uncertain, frustrating or time-consuming, for example? Which elements is the customer most dissatisfied with? Relationship-oriented market research should focus around these fundamental issues, but in our experience too little of this type of research is conducted either in business-to-business or business-to-consumer marketing. We examine the concept of the customer activity cycle in greater detail in Chapter 5.

Flexible response

To be able to exploit fully the opportunities presented by the myriad of potential individual customer activity cycles, suppliers need to be highly flexible and responsive. By definition, one-to-one marketing requires individual solutions for individual buying problems. Customers may not want the physical product to be differentiated (although many do), but require the accompanying service package to be tailored.

Today the search is on for cost-effective strategies to achieve what is now termed ‘mass customisation’.22 Mass customisation is the ability to take standard components, elements or modules and, through customer-specific combinations or configurations, produce a tailored solution. In a manufacturing environment the aim would be to produce generic semi-finished products in volume to achieve economies of scale, and then finish the product later to meet individual customer requirements.

An oft-quoted example of mass customisation is the Japanese National Bicycle Company, which offers customers the opportunity to configure their own bicycle from different style, colour, size and components options. Within two weeks the company delivers the tailored bike to the customer. The company has become the market leader in Japan as a result of this marketing and logistics innovation.

Value-creating relationships

A prime objective of relationship marketing is to create superior customer value at the one-to-one level. The premise is that while it is impossible to have a relationship with a market or even a segment, it may be possible to establish a relationship with an individual customer or consumer.

Though the general principles of relationship marketing apply across the entire spectrum of business-to-business (b2b) to business-to-consumer (b2c) companies, there are some specific issues associated with each of these two key areas.

B2b relationships

In b2b environments, there has been a noticeable trend towards customers seeking to do business with suppliers on an entirely different basis from in the past.

Historically, companies would have multiple suppliers so as not to keep all their eggs in one basket and to keep vendors at arms’ length. Information sharing was minimal. Today there are signs that this almost adversarial approach to buyer/seller relations may be changing. The emphasis now is on reducing the supplier base, moving sometimes to single sourcing for any one item; and working much more collaboratively, supported by transparent information.

Companies have changed their approach because they have realised that they can greatly enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of their supply chain through collaborative working. Conventional supply chains are based upon each entity – whether buying or selling organisation – seeking to optimise their own operations. Such approaches have led to resources and assets being duplicated, and have even resulted in sub-optimisation across the chain as a whole. Conventional wisdom suggests that those companies with the greatest internal resources and capabilities will gain competitive advantage, but the new school of thought recognises the mutual dependencies between organisations and the importance of leveraging the combined capabilities of the supply chain as a whole.

The more firms outsource activities they used to do themselves, the greater these external dependencies are, and hence the greater the need to pay particular attention to the way in which they manage their relationships with supply chain partners.

This changed perspective gives suppliers the opportunity to develop a value-based relationship strategy. Such strategies are based on identifying opportunities to improve the customer's value-creation process, and help them do a better job of serving their customers at less cost. Value-based strategies seek to generate innovative solutions that will help customers achieve greater differentiation in their markets and improve their profitability. At one level suppliers might contribute to their customer's new product development process, at another they might help the customer respond to changing demand through integrating their logistics processes.

Suppliers have a powerful opportunity to create value-based relationship strategies by reducing the customer's ‘costs of ownership’.23 These costs of ownership extend beyond the actual purchase price and include the costs that the customer occurs in in-bound quality control, re-work, the costs of holding inventory, operating costs, maintenance, training and even the costs of disposal. But if they are to develop strategies that can lead to demonstrable improvements for the customer, suppliers need to understand these costs of ownership even better than their customers do. One example of such a strategy is vendor-managed inventory (VMI). With VMI, the supplier manages the flow of product into the customer's operations, removing the need for the customer to place orders (so reducing their transaction costs) and reducing or eliminating the need for the customer to carry safety stock (so reducing the cost of financing inventory). But for VMI to be possible, the customer has to tell the supplier the rate at which that product is being used or sold.

Many companies are now taking advantage of developments in information technology – including the Internet – to install such integrated processes, and are creating stronger, mutually beneficial partnerships as a consequence. Such arrangements are being extended into initiatives such as collaborative planning, forecasting and replenishment (CPFR) agreements. These initiatives involve buyers and sellers coming together jointly to agree strategies to develop a particular line of business, and to improve the efficiency of product flow, reducing inventories and improving sales through fewer stock-outs. In the retail market, a closely related concept is category management. Typically, category management involves customer and supplier working together to agree a marketing strategy for a product category, including promotions, pricing, shelf-positioning and possibly vendor-managed inventory too.

B2c relationships

Conventionally, most marketing effort has been expended on creating a strong franchise with consumers in the final marketplace. This franchise was effectively based on loyalty to the brand. The argument was that if a company could create strong brand ‘values’ then consumers seeking those values would be drawn to the brand and reject alternative offers. So marketing effort focused on creating a brand ‘image’.

This approach worked well for many years, but as competition intensified and consumers became more experienced and sophisticated, these relatively crude approaches became less effective. The evidence today points to a gradual decline in brand loyalty and, in its place, an increased willingness by consumers to choose from a portfolio of brands.

While individual consumers may well have brand preferences, they are quite happy to select alternative brands if the first choice is not available. In fact, research has shown that up to two-thirds of all consumer buying decisions are made at the point of purchase.

In this new world, the need for strong b2c relationships is still as great as ever. However, the conventional means of creating this relationship – brand values – needs to be augmented through a much wider range of marketing activities.

One reason why traditional brand loyalty has declined is that consumers are tending to see their relationship as being more with the retailer than with the brand. Thus store loyalty rather than brand loyalty may be the emerging pattern of the future.

Though this trend may continue, it does not preclude the manufacturer of branded products from seeking alternative ways of developing a dialogue with consumers and through that creating a different type of relationship. Some companies, for instance, have sought to establish direct-to-consumer channels to complement existing indirect channels. In many cases the Internet has given brand owners easy access to consumers. For example, in the United States Procter & Gamble has established Reflect.com to offer customised cosmetics and related products to end users. Clearly there are potential problems of channel conflict if these new channels are seen to compete with existing channels. The growing use of database marketing (DBM) can help companies understand and communicate with customers who have specific characteristics and attributes. Using data from a number of sources and increasingly sophisticated software, it is possible to zero in on relatively small groups of customers with similar profiles. This direct marketing allows companies to develop a much more targeted approach.

Making use of computerised customer information files which are constructed on a ‘relational’ basis (that is, different elements of information can be brought together from separate files) enables the marketer to target more precisely the message to the individual customer or prospective customer.

But it is the rapid growth of detailed information on individual customers combined with computer technology that has made DBM a reality. A major spur to the use of DBM in consumer markets particularly has come through the fast developing field of ‘geo-demographics’.

Geo-demographics is the generic term applied to the construction of relational databases which draw together data on demographic variables (such as age, sex and location), socio-economic variability (occupation and income, for example), purchase behaviour, lifestyle information and, indeed, any data that might usefully describe the characteristics of an individual customer.

DBM also allows companies to personalise customer communication much more precisely, making direct mail more specific and relevant to the recipient. Catalogues, newsletters and even magazines can be tailored to the known interests and preferences of the individual. The use of DBM is spreading, particularly in the service sector. Frequent-flyer programmes and hotel club schemes have been around for some time, but companies are now developing their potential more fully. So not only do companies know all about an individual's purchase behaviour, they can correlate it with background information they have already collected on that individual. They can enhance relationships with customers through customising the service they offer them – for example, seating and food preferences on an airline or room preferences in a hotel can easily be catered for.

Fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) companies are increasingly able to pinpoint likely targets for their products through the use of DBM. But what is more important is that they can use it to strengthen relationships with key customers by designing promotions and incentives that will bind customers more closely to them. More and more consumer durables companies are using DBM to improve customer retention rates. Many car companies, for example, collect information on their customers when they buy a car and then use this information to manage the relationship with them afterwards.

Market segmentation

In both b2b and b2c marketing, market segmentation can be a powerful aid to successful relationship marketing. A market segment is a distinct sub-group within the overall marketplace. Once companies understand the distinctive characteristics of segments, they can adopt a much more targeted approach to developing and implementing marketing strategies.

Market segmentation essentially involves dividing a total market up into a series of sub-markets (or market segments). A market segmentation exercise involves considering the alternative bases for segmentation, choosing specific segments (or a single segment) within that base, and determining appropriate marketing strategies for these segments. Organisations typically use three criteria to select target segments. Market segments should be:

![]() accessible- companies should be able to communicate with segment markets with a minimum of overlap with other segments, and distribution channels should be available to reach them;

accessible- companies should be able to communicate with segment markets with a minimum of overlap with other segments, and distribution channels should be available to reach them;

![]() measurable –;companies should be able to measure or estimate the size of the segment and quantify the impact of varying marketing mix strategies on that segment;

measurable –;companies should be able to measure or estimate the size of the segment and quantify the impact of varying marketing mix strategies on that segment;

![]() potentially profitable – the segment should be potentially profitable enough to make it financially worthwhile to service.

potentially profitable – the segment should be potentially profitable enough to make it financially worthwhile to service.

Markets may be segmented in many ways, but the following categories are the most important.

B2b segmentation

Segmentation by service

This approach is concerned with how customers respond to service offerings. Companies can offer a range of different service options, and provide different service levels within those options, giving them considerable scope to design service packages appropriate to different market segments. If a supplier measures the perceived importance of different customer service elements across market segments, they can respond to that segment's identified needs and allocate an appropriate service offering to it.

Segmentation by value sought

As we pointed out earlier in our discussion about customer value, different customers may respond differently to the seller's ‘value proposition’. Knowing what customers value and what weight they put on the different elements of a value proposition can help a company develop more targeted solutions. It is critical to have a deep understanding of the motivations behind the purchase decision.

Segmentation by industry type

The segmentation of markets on the basis of Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) is quite widespread, but of only limited use. Sometimes these segments are thought of as ‘vertical’ markets and defined around business sectors such as the construction industry, or the telecoms industry, for example. The problem with this type of segmentation is that it provides no guide as to how the behaviour of buyers might differ simply because they happen to be in different industries.

Geographic segmentation

This approach differentiates customers on the basis of where they live. So customers may be segmented into urban, suburban or rural groups, for example. Customers are commonly segmented by postcodes, which might also represent different groups in terms of relative wealth, and socio-economic and other factors.

Demographic and socio-economic segmentation

Demographic and socio-economic segmentation is based on a wide range of factors including age, sex, family size, income, education, social class and ethnic origins. So it is helpful in indicating the profile of people who buy a company's product or services.

Psychographic segmentation

Psychographic segmentation involves analysing lifestyle characteristics, attitudes and personality. Recent research in several countries suggests that the population can be divided into between ten and fifteen groups, each of which has an identifiable set of lifestyle, attitude and personality characteristics.

Benefit segmentation

Benefit segmentation groups customers together on the basis of the benefits they are seeking from a product. For example, car buyers seek widely varying benefits, from fuel economy, size and boot space, to performance, reliability or prestige.

Usage segmentation

Usage segmentation is a very important variable for many products. It usually divides consumers into heavy users, medium users, occasional users and non-users of the product or service in question. Marketers are often concerned with the heavy user segment.

Loyalty segmentation involves identifying customers’ loyalty to a brand or product. Customers tend to be very loyal, moderately loyal or disloyal. These groups are then examined to try to identify any common characteristics so that the product can be targeted at prospectively loyal customers.

Occasion segmentation

Occasion segmentation recognises that customers may use a product or brand in different ways depending on the situation. For example, a beer drinker may drink light beer with his colleagues after work, a conventional beer in his home and a premium or imported beer at a special dinner in a licensed restaurant.

We would advise both b2c and b2b companies to categorise markets according to value preferences, at least initially, when developing a market segmentation strategy in the context of relationship marketing. If organisations understand what different customers value and how this influences their purchase decisions, then they can subsequently see if those value preferences correlate with other segmentation criteria.

Once a business has determined the relevant segmentation base (or bases), it can then identify the market segments or sub-groups within the buyer, intermediary and consumer levels in the distribution chain. After that it can examine the opportunities these segments afford, identify the most attractive segments and develop appropriate strategies for winning and retaining customers within them.

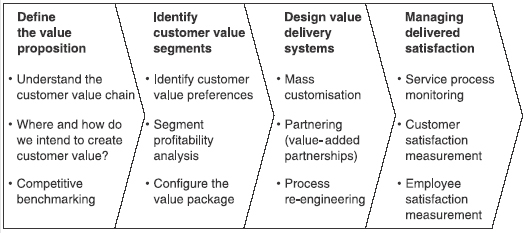

The relationship management chain

Organisations making the transition from classical, transactional-based marketing to closer relationship-focused marketing need to assemble carefully many different pieces of the jigsaw. We have briefly described some of these pieces, such as the value delivery process and market segmentation. We use the idea of the ‘relationship management chain’ to bring them together. We explain the relationship management chain in greater detail in Chapter 6, but the key activities within it are shown in Figure 1.10.

FIGURE 1.10 Key activities in the relationship management chain

The idea behind the chain is that relationships are based on the exchange of value between customers and suppliers. The key activities in the chain follow a four-stage process:

1 Defining the value proposition.

2 Identifying appropriate customer value segments.

3 Designing value delivery systems.

4 Managing and maintaining delivered satisfaction.

These four stages should be seen as closely connected elements of a dynamic process, and companies will need to reassess and re-engineer relationship strategies continually as the nature of the market and customer requirements change.

Markets today are much more volatile and fluid than in the past, so both the definitions of value and the means of delivering that value will have to change.

SUMMARY

The change in orientation that we have described carries significant implications for the way marketing activity is organised. As the business becomes more focused around processes, marketing will be forced out of its functional silo to become a pan-company concern.24 One of the biggest hurdles to becoming customer driven is the entrenched functional hierarchies that dominate much of industry. Customer value is created only through processes, so it makes sense that the process rather than the functional task should provide the foundation for the organisational structure.

A corporate culture that recognises that the delivery of customer and consumer value is the primary purpose of the business has to underpin any successful relationship marketing strategy. The structure of the organisation, its performance measurement system and its reward mechanisms must reflect this culture.

In Chapter 2 we explore in greater detail ways in which the business can leverage the delivery of value to customers to create greater value for itself through a deeper understanding of the customer acquisition and retention process.

Relationship marketing is more than a ‘makeover’ for conventional marketing. It is, in effect, a new model for how the organisation as a whole competes in the marketplace. This book is based on that fundamental notion.

References

1 Kotler, P. (1967), Marketing Management: Analysis, Planning and Control, 1st edn, Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

2 See, for example: Palda, K. (1969), Economic Analysis for Marketing Decisions, Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

3 See, for example: Robinson, P.J. (1967), Industrial Buying and Creative Marketing, Alwyn and Bacon.

4 See for example: Cowell, D. (1984), The Marketing of Services, Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

5 See, for example: Lovelock, C.H. and Weinberg, C.B. (1984), Marketing for Public and Non-Profit Managers, John Wiley.

6 ‘Disloyalty becomes the norm’, Marketing,21st June 2001, pp 24–5.

7 Brady, J. and Davis, I. (1993), ‘Marketing in Transition’, McKinsey Quarterly, No. 2, pp 17–28.

8 The Economist(1994), ‘Death of the Brand Manager’, 9th April, 79–88.

9 Berry, L.L. (1983), ‘Relationship marketing’ in Berry, L.L., Shostack, G.C. and Upah, G.D. (eds), Emerging Perspectives on Services Marketing, Chicago, IL: American Management Association, pp 25–28.

10 Christopher, M., Payne, A. and Ballantyne, D. (1991), Relationship Marketing, Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

11 Peppers, T. and Rogers, M. (1997), Enterprise One-to-One, New York: Doubleday.

12 The Boston Consulting Group (1968), Perspectives on Experience, Boston, MA.

13 Borden, N. (1965), The Concept of the Marketing Mix, in Schwartz, G. (ed.) Science in Marketing, New York: John Wiley.

14 Peck, H., Payne, A., Christopher, M. and Clark, M. (1999), Relationship Marketing: Strategy and Implementation, Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

15 Davenport, T. (1993), Process Innovation: Re-engineering Work Through Information Technology, Harvard Business School Press.

16 Christopher, M.G. (1999), The Agile Supply Chain: Competing in Volatile Markets, Industrial Marketing Management, 29.

17 Webster, F.E. and Wind, Y. (1972), Organisational Buying Behaviour, Prentice Hall.

18 Gale, B. (1994), Managing Customer Value,New York: Free Press, p.xiv.

19 Naumann, E. and Kordupleski, R. (1995), Customer Value Toolkit, first edition, South-Western College Publishing.

20 Lanning, M.J. and Michaels, E.G. (1998), ‘A Business is a Value Delivery System’, McKinsey Staff Paper, June.

21 Vandermerwe, S. (1996), The Eleventh Commandment, Chichester: John Wiley.

22 Pine, J. (1993), Mass Customization, Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

23 Ellram, L.M. (1999), Framework for Total Cost of Ownership, International Journal of Logistics Management, 4, No. 2, 49–60.

24 McDonald, M., Christopher, M., Knox, S. and Payne, A. (2001), Creating a Company for Customers, London: Pearson.