Moderated research is about talking to people. No matter how well you’ve memorized the study objectives, set up the equipment, and recruited the right users, that doesn’t mean squat if you don’t establish good working communication with your participants.

Skeptical UX researchers accustomed to in-person research often ask us how it’s possible to effectively establish rapport with users without being physically present. Conventional wisdom dictates that you can read more from in-person visual cues, create a more comfortable and natural conversation, and make better motivational inferences when you’re face to face, but the truth is, for much of technology research, people are perfectly comfortable talking on the phone while in their own computing and physical environments. (Since moderating with only the phone is such a hot topic, we’ve dedicated an entire section to it—“Ain’t Nothing Wrong with Using the Phone”—which you can find later in this chapter.)

Since one of the chief benefits of remote research methods is that it enables time-aware research, you’ll ideally be able to observe users do what they were going to do before you called them, which makes establishing rapport and motivational inferences much easier. You’ll find that your job is ultimately less about saying the right things and more about simply observing users as they go about their lives. Again, because watching people use interfaces in the real world for their own purposes is so different in terms of motivation, context, and actual behavior, time-aware remote research comes with a host of new moderating challenges, which is what this chapter is all about.

Let’s start with the moment that users first pick up the phone. If participants are prerecruited, introducing yourself is simple and straightforward. If you’re live recruiting, participants won’t necessarily be expecting to be contacted, and you’ll often have to do some quick orientation before you can begin the study. This first step is critical because not only are you about to ask users to do something pretty crazy—let a total stranger see their screen—but you’re setting the tone for the whole phone conversation. You should introduce yourself, associate yourself with the survey that they’ve just filled out on the Web site (or remind them about the scheduled interview), and then ask them if they’d still like to participate in a 30–40 minute phone interview.

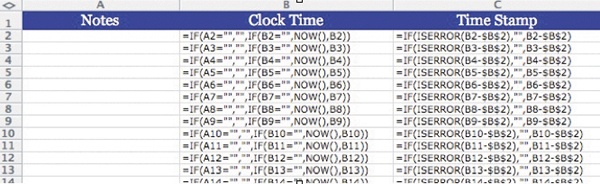

We’ve honed down this opening exchange so furiously over the past 10 years that it’s practically the most efficient part of what we do. Feel free to modify it, of course, but we’ve found the exchange shown in Table 5-1 works really well.

Table 5-1. Typical Session Introductory Flow ![]() http://www.flickr.com/photos/rosenfeldmedia/4287139348/

http://www.flickr.com/photos/rosenfeldmedia/4287139348/

Some people express surprise at being called so soon after filling out an online survey, but this doesn’t usually affect their willingness to participate one tiny bit. Just reassure them that you’ve been standing by to contact participants.

Assuming they agree, you’ll need to explain about screen sharing, making sure they understand that (1) you’ll be able to see everything they can see on their whole computer screen; (2) it’s just for the duration of the session; and (3) you’ll also be recording the screen sharing and conversation, just for research purposes.

Reluctant users may ask you about the testing process. Common questions include the following:

Note

PRO TIP: DISMISSING RECRUITS

It can be tough to tell recruits flat-out that the interview just isn’t going to work out. Most researchers, out of politeness, naturally want to offer explanations, apologize, and talk more than is necessary. You don’t want to do that. If you need to dismiss users (can’t set up the screen sharing, don’t have time to fully participate, aren’t actually qualified to participate, etc.), and you’ve already spent up to 15 minutes trying to help them set up the study, and you have plenty of other qualified recruits that just came in via live recruiting, then dismiss the user. Use direct, certain, and friendly language to express that you can’t go on with the session, citing the main reason without overexplaining:

“Unfortunately, the interview would have to begin right now...”

“I’m sorry to say that the screen sharing software is essential to the study...”

“Actually, we’re currently looking to speak to people who are regular visitors to the ACME site...”

And then finish with something like this:

“...So we won’t be able to conduct the interview. But thanks so much for responding, and I really appreciate your time. Have a good evening.”

It’s important to know that 1 in 1,000 survey respondents will try to insist on compensation for simply answering the phone or filling out the online screener. Since we like to treat users well, we’ll sometimes offer a partial incentive or some token of appreciation, and the total cost to the study is usually negligible. But as long as you made it clear on the screener that incentives are given only to participants who complete the study, you’re not obligated to do so.

Once you’ve walked participants through the installation process, you’ll prepare them by introducing the purpose of the study and explaining broadly what participation entails. This step is important for keeping the participants from becoming confused, frustrated, or distracted later. At this point, they’re usually assuming that you’re going to tell them what to do and will be awaiting instructions from you.

First, you need to give a quick one-sentence description of what the study’s about, and then—assuming you’ve designed a time-aware, live-recruited study, as we highly recommend—you’ll tell them that you’d like them to do exactly what they were in the middle of doing when you called. (If some time has passed since they filled out the survey, you can ask them instead to do what they were in the middle of doing before they filled out the survey.) The very last thing you need to tell participants before starting is to “think aloud” as they’re going about their tasks, so you can hear what’s going through their minds. (For tips on how to word these statements exactly, see the facilitator guide walkthrough in Chapter 2.)

Unfortunately, sometimes you have to fight an uphill battle against user boredom and distraction. It’s harder to keep people engaged over the telephone, especially when they’re in their own homes or offices and (for all you know) may be watching TV, fiddling with a Rubik’s Cube, etc. We try to give out instructions in small, measured chunks, rather than all at once—a strategy we call “progressive disclosure of information.” If you catch yourself issuing instructions continuously for longer than 30 seconds, stop and engage users by asking if they have any questions, or have users perform some setup task (e.g., set up the screen sharing, open the interface) to maintain attention.

Note

Users should always know before the session begins exactly the kind of access you’ll have to their computer, whether you’ll record the session, and what you’ll do about the recording. If they have questions or reservations, don’t try to pressure them into consenting. If you’re live recruiting, you can always just snag another user.

Of course, it’s tempting to look at all the juicy user info that’s right there in front of you, but a few things are out of bounds for most purposes. For example, if users have carelessly left their email client open (despite your earlier instructions to hide any sensitive info), you shouldn’t look though their personal email correspondences. Avoid pointing out any material that might make users feel as though they’re being intrusively scrutinized or that has the potential for making an awkward situation. Examples of things you don’t want to say: “Hey, I see there in your Web history that you just went shopping for boxer briefs!” “Want to show me what’s in all those image files on your desktop?”

Privacy isn’t just an ethical issue. If users even suspect that you’re overstepping your bounds, they may feel anxious, untrusting, and defensive, and it’ll shatter that all-important trust relationship that you must develop to get natural behavior and candid feedback.

In the past, one of the central challenges of designing a traditional user research study was to come up with a valid task for users to complete: some activity that was typical of most users and realistic for users to complete without explicit instruction. Live recruiting, as you now know, makes this issue of “realism” moot because participants are screened based on the relevance of their natural tasks. Much of remote moderating, then, consists of listening to and observing users as they do their own thing.

With this method, you surrender a measure of strict uniformity in exchange for something that’s potentially much more valuable, which is task validity. But this doesn’t mean that participants can do literally anything they want for the entire session. As a moderator, you need to be able to distinguish which natural tasks are worthwhile and which ones will require you to step in and, well, moderate.

The best remote sessions are the ones in which you can address all the study goals without asking a single question. Ideally, in the process of accomplishing their own goals, users will use every part of the interface you’re interested in and be able to narrate their interaction articulately the entire time. It’s nice when this happens, but usually you’ll have to do some coaxing to cover all your bases, and when that’s necessary, we recommend a somewhat Socratic method: try to keep your questions and prompts as neutral as possible and focus on getting users to speak about whatever they’re concentrating on. (A list of handy prompts can be found in the remote facilitator guide walkthrough in Chapter 2.)

Note

DON’T INTERFERE WITH THE USER

Moderators are often terrified of inadequately covering everything that’s been laid out in the moderator script. Since this is time-aware research, however, we encourage you to chill out. First of all, you want to see what users naturally do and don’t do. Second, you can always go back later in the session to catch what you missed. The reason we so zealously endorse abandoning the facilitator guide and embracing improvisation is that we feel time-aware research is especially rife with opportunities to observe new and unexpected behaviors, much more often than you’d find in a lab setting. Some folks in the UX field have dubbed these unexpected behaviors as “emerging themes” or “emerging topics,” and they come up all the time when you’re speaking to users who are on their own computers and in their own physical environments. See The Technological Ecosystem in Chapter 7.

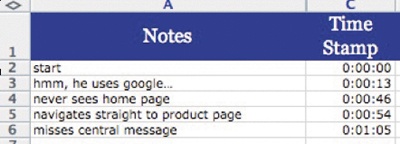

Although we encourage you to ditch the facilitator guide, it’s still important to be ready for problems during the session. We’ve cranked out a list of handy things to say in the most common situations (see Table 5-2). They all come up sooner or later, and knowing what to say will help you project the appropriate air of serene moderator neutrality:

Table 5-2. List of Handy Troubleshooting Phrases ![]() http://www.flickr.com/photos/rosenfeldmedia/4286398425/

http://www.flickr.com/photos/rosenfeldmedia/4286398425/

What You Say | |

|---|---|

Something goes wrong with your technical setup (screen sharing session disconnects, computer slows down, desk catches fire, etc.). | “Hey, can I put you on hold for just a minute? I’ve got to adjust something on my end.” [Place user on hold.] |

The phone connection is bad. | “You know, I think we might have a bad phone connection. Would you happen to be on a cell phone?” [If so] “Would you mind switching to a land line? Would that be possible?” [If not] “Let me call you back on a different line. I think my phone might be acting up. I’ll just be a minute.” |

Your participant asks you a biasing question (e.g., “Can you tell me what this button here is supposed to do?”). | “Hmm, that’s a good question. First, can you tell me what your impression is?” OR, “You know, I’m actually not sure myself; I wasn’t involved with the design. What would your best guess be?” |

The user is taking an unduly long time on a relevant task. | “So, actually, in the interest of time, I’m curious to see what you’d do after you finished with this.” |

The user has become sidetracked on an irrelevant task. | “So, let me ask you to back up a little. Thanks for showing me that, by the way. Can you tell me a little more about what you were doing on that earlier screen?” |

There are a number of situations in which you might not want to discourage users from the path that they’re on, but you do want to speed them along. Most often it’s when they read long blocks of text, pursue a goal entirely unrelated to the scope of the study, or (as is often the case with less tech-savvy users) can’t figure out how to perform a basic task on the computer, such as enter an address into a browser bar. In the latter case, feel free to offer help; in the two former cases, you can try instead to speed up the process by asking them to skip over the rest of the task, if possible:

Thanks for showing me this. So, in the interest of your time, I was curious to see what you would do after you were finished reading this text over?

(Note how we say “your time”; this is just to emphasize that moving things along will keep the session from going over time, which is in their interest.)

You may not cover all your testing objectives in a session, or you may want more info around a particular behavior. Sometimes, your user may have only a very specific task to perform at the Web site and may finish it early in the session. You should set aside a few minutes at the end of each session to assign predetermined tasks to fill in these gaps. When users tell you that they’re finished, it’s time to circle back to the tasks you’ve missed. This process is pretty much the same as standard usability research: prompt users to perform tasks, observe tasks, ask users about tasks—you know the drill. If you run out of predetermined tasks and you still have some time left over, ask your observers if they have any other questions or tasks they’d like to see users perform. Then you can wrap up things as usual.

You could use plain old pen and paper to take basic notes during a remote session, if that’s what works for you. But taking full advantage of remote research tools means taking notes on the computer. It can make analyzing the session videos and extracting the main themes of the research a lot easier. (Plus, it’s cooler.) When taking notes, your main priorities are to do the following:

Reduce the amount of distraction incurred by taking notes.

Mark clearly when in the session the noted behaviors occurred. You want to avoid having to rewatch the sessions again in their entirety; doing so is time consuming and unnecessary if your notes are in shape.

And let’s be clear—smart note taking isn’t about pointlessly obsessing over time. An extra second spent timestamping or tagging your notes during live research will save you 1,000 minutes of analysis. (That’s our official formula.) Reviewing hours of research video without timestamps is eye-straining and tedious, and nobody conducting research outside academia ever has time to review footage and log data after the fact.

If you’ve been in the UX game for a while, you probably already have some kind of shorthand method of manually timestamping. We like the plain old [MM.SS] format. If you’re making video recordings of each of the sessions, it’s important to time your notes relative to when the video began (instead of an absolute time, like “3:45 PM”). If necessary, you can download one of the many free lightweight desktop stopwatch programs online and start it as soon as your video recording starts. Whenever you make a note, copy the time on the stopwatch.

There are also more sophisticated alternatives to frenzied manual timestamping. Collaboration is one approach. Since remote research allows for a large number of observers who are also at their computers, you can prompt your observers in advance to make notes about user behaviors they’re interested in. Using online chat rooms or collaboration tools like BaseCamp or Google Docs can provide a convenient outlet for observers to put notes and timestamps in the same place. Some research tools, such as UserVue’s video marking function, allow observers to annotate the video recordings directly as the sessions are ongoing.

Are there any comprehensive solutions out there for collaborative, automatically timestamped, live note taking? NoteTaker for Mac has a built-in timestamp, but it’s set to the system time, not relative to the session. There’s nothing else as far as we know, but, happily, we’ve come up with a way to use instant messaging clients to do that. Our technique allows multiple people to work in the same document, with entries labeled by author and precise time noted automatically, down to the second.

The idea is to get everyone into the same IM chat room and then configure your IM program (Digsby, Adium, Trillian) so that it displays the exact timestamp every time anyone enters a note. Then set up a chat room and invite all the observers into it. (For step-by-step instructions on how to do all this, check our site at http://remoteusability.com.)

Once the session is over, everything that’s been typed has been automatically logged by the IM client, so you have your timestamped transcript ready to go. You can either save or copy the chat room text to a document file—or better yet, an Excel spreadsheet, where you can easily annotate and organize each individual note (see Figure 5-1 and Figure 5-2).

We know this technique is a little kludgy, but it’s free, and it gets the job done. (We’ve also posted an Excel spreadsheet template with a custom-made macro script on our RemoteUsability Web site that does all the work of adjusting the timestamp automatically for you, but you may have to spend hours adjusting macro settings in Excel to allow a public file with an embedded macro to actually be allowed to run. Since that rampant outbreak of malicious macros in 1981, Microsoft has really clamped down on macro security in Excel files. Anyway.)

Figure 5-1. This is what our template automatic timestamping spreadsheet looks like before entering any info.

Figure 5-2. After entering your notes, the spreadsheet automatically enters the amount of time that has passed since the first note was entered. This way, you can track the times in your session recording when certain behaviors and quotes were made. (Remember to enter the first note right when the recording begins!)

If the whole business of note taking just sounds tiring to you, you can always get someone else to do it for you. There are online services that will transcribe all the dialogue entirely. We personally like CastingWords (http://castingwords.com), although there are plenty of others. Transcription is a good option if you need all the dialogue transcribed verbatim within a limited time frame for some reason, or if you’re just lazy and have lots of time and money you just don’t need. The downsides to this approach are that it costs money (~$1.50/minute), you may have to extract the audio from the session video into an .mp3 or .wav file, and you’ll have to wait for the transcription—the more you pay, the faster the service works.

Lastly, we’re starting to see automatic transcription tools hit the scene. Adobe Premiere CS4, a video editing suite, has a feature that boasts automatic transcription of video files, with an interactive transcript feature by which you can jump to the part of the video in which a word was said simply by clicking the word. In theory, this obviates note taking; in practice, we’ve found that it’s not very accurate at all, and the time it takes for the software to transcribe the video is roughly three times the length of the video. So you should probably stick to doing your own notes until the technology improves.

With remote research, unlike in a lab, there’s no need for two-way mirrors or omnidirectional cameras. Depending on the screen sharing tool you use, it’s pretty easy to allow people to observe the sessions. On top of that, remote observers can easily use chat and IM to communicate with the moderator as the sessions are ongoing, giving their input on the recruiting process, alerting you to user behaviors you may have missed, and even helping you take notes during the session. If you’re testing an interface whose technical complexity may be beyond your expertise (e.g., a glitchy prototype or a jargon-heavy interface), you can have an expert standing by during the session to troubleshoot and assist.

There are a couple of things you should know to make cooperation smooth and useful during your remote session. First, make sure that the barrier between the observers and the study participants is airtight. There’s nothing more disruptive to a study than having observers unmute their conference call line or have their chat made visible to the participant.

Observers should be briefed in advance about their participation in the research to make their contributions as useful and nondisruptive as possible (see Preparing Observers for Testing in Chapter 2), but you may find that observers occasionally overstep their bounds anyway. Their requests should be acknowledged ASAP, but you don’t need to promise to act on every request. To avoid sounding rushed or irritated with observer requests, use concise and unambiguously friendly language to acknowledge them. Toss a smiley in there, if you’re not ashamed: “Understood. I’ll see what I can do!:)” Ask for clarification if the request is unclear: “Not quite sure I understand; can you clarify?” Ultimately, if there are too many requests to handle, the moderator should chat with the observers immediately following the session, mentioning any specific issues that kept them from fulfilling any requests: “Sorry I couldn’t get to all your requests; it was important to leave enough time to cover our study goals. Feel free to keep sending them along, though!” The aim is to keep observers from overburdening the moderator, while not discouraging them from contributing usefully.

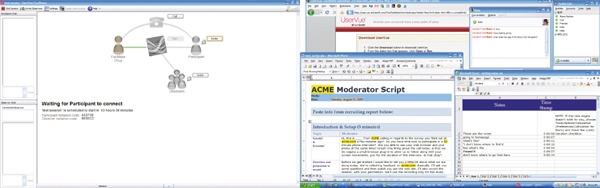

During the session, observers will naturally want to contribute, offer advice, and suggest questions they’d like to have asked (see Figure 5-3). That’s fine, but the moderator should always serve as a filter between observers and participants. Always translate task requests into natural, conversational, and most importantly neutral language. For example, an observer may say, “Ask the user what he thinks of the navigation bar,” but, of course, as a trained UX researcher, you know better than to ask for point-blank opinions. Instead, you could either simply wait for the user to interact with the navigation naturally, or you could ask questions geared toward eliciting a behavioral response: “What were you trying to do on this page?” “What would you do after this?” and so on. In any case, let the observers know that you’re on top of the issue.

Figure 5-3. In this session, we projected the user’s screen onto the wall and played the audio through speakers so that the observers could follow right along. Observers could pass notes or send IMs to the moderator as the session was ongoing.

You also may encounter the problem of observers who don’t seem to be paying enough attention to the session or who remain silent. This won’t necessarily harm the study, but it might indicate that the observers aren’t aware of the active role they can play or are too timid to ask. If your observers are silent for a long time (~10 minutes), it’s good practice to ask them if there’s anything they’re curious about or would like to have you probe further. If they say “no,” carry on; if observers remain silent, you can follow up with a brief appraisal of the session, to encourage more observer discussion: “This user seems to have a lot of trouble logging in. I’ll try to find out more about that.”

Finally, avoid soliciting advice or over-relying on observers for guidance (e.g., “What should I ask the user now?”). Observer requests are a secondary tool for fulfilling the research objectives; the primary guidance, of course, should come from the moderator and from the research objectives, as embodied in the facilitator guide.

If working with observers sounds stressful, including them is worthwhile for more reasons than just getting advice. Having stakeholders— developers, project managers, marketing people, whoever—observe and engage with the research can make them more invested in the outcome of the research. Findings are easier to understand and present, since observers can draw upon their own recollection of the sessions to place the findings in context. Stakeholders who are unfamiliar with remote methods (or UX research in general) and have doubts about their soundness and validity are often won over when they get to see how it happens. Since they gave their input throughout the process, they’re less apt to question the researchers’ approach.

Short debriefing sessions after each session are useful, letting observers fully elaborate on things they noted during the study. When testing is finished, observers can join in on brainstorming sessions and contribute any insights they may have gathered as outside observers. This is also a good opportunity to catch any mistaken assumptions your observers may have about the research. They might have interpreted a user’s offhand comment that “This login process is easy” to mean that there are no problems with the login process, whereas you spotted dozens of behaviors to the contrary. You can then be prepared to address these assumptions as you’re drafting your report.

When you finally present the findings, it’s nice to acknowledge the observers’ contributions to the project, specifically calling out instances when they helped. These acknowledgments make it clear to observers how they benefited the project, increasing their investment and confidence in the research. That makes it more likely the findings will be applied or possibly even convince observers that a stronger organizational focus on research is required, creating more opportunities for good research.

You have a problem participant. Dang. Usually, you can catch these people right away with proper recruiting, but every now and again you’ll be speaking to someone who seems like a decent enough participant at first and then becomes tough to communicate with once the session has begun. Your treatment of these participants will vary based on the study goals and also the nature and severity of the issue.

Quiet participants are the most common type of problem participant, but thankfully they’re also the easiest to handle. Nine times out of ten, the issue will be that users get too engaged in their task and forget to think aloud in a way that helps you follow along. This is actually a good thing because it shows that they’re engaged in a task they care about. You want to strike a balance between engagement and talking so that users are speaking undeliberatively about what they’re feeling and doing, and what problems they’re facing in the moment, rather than their opinions about the interface. In cases like this, all you have to do is encourage users to speak up. Here are a few polite prompts you can use:

Some users will take more encouragement than others, but that’s life in the streets.

Other times, you’re dealing with a bored participant who doesn’t seem engaged and isn’t speaking. Symptoms include minimal time spent on each task, flat conversational tone, and consistently short responses to your questions (“It’s fine,” “It’s okay, I guess.” “I dunno”). Here’s where you’ll use your moderator skills to come up with questions that are both very specific and hard to give short responses to. Ask about specific onscreen behaviors:

“I noticed that you just hesitated a bit before clicking on that button. Can you tell me why?”

“Why don’t we back up a bit? I was curious about what drew your attention to the tab you just clicked on?”

“Before we move on from here, I wanted to ask you about this part a bit more. What do you think about the range of choices they give you here? Is anything missing?”

On top of that, you can try to examine the reasons participants may be bored. Boredom often indicates that they’re not doing a task they care about—i.e., a natural task. Since the point of time-aware research is precisely to study people who are doing something they’re intrinsically motivated to do, you may have recruited someone whose task was slightly out of sync with the goals of the study, and that may mean you need to screen the participants more carefully. If you find yourself talking to several bored users, however, you may have a larger problem on your hands—namely, that nobody cares about doing the task you’re studying. Don’t panic; having this type of response just means you might have to rethink your facilitator guide, and even your research goals, on the fly. Try to keep the focus of the study on watching users accomplish objectives that matter to them; you’ll get behavior that’s both more natural and more engaged.

Besides bored or quiet users, you can also have users who are very chatty and try to tell you their life stories. You can hear them leaning back in their chairs to have a nice chat on the telephone. When this begins to happen, gently interrupt them when they reach the end of a sentence and try to refocus them on a task: “Can I interrupt you? Sorry, I was actually curious if you could....” If it becomes a repeat problem, mention how much time is remaining in the session: “We have about 10 minutes to go, and so to keep from running over our time, I just wanted to make sure we got through the whole process here....” Be polite but persistent; don’t let users interrupt themselves with chatting.

Now here’s something interesting. Since you may be calling people in different time zones—occasionally after Miller Time—you may reach some participants who are perfectly qualified, are willing to participate, and happen to have, you know, had a few. Which is not as bad as it sounds: people really do use computers in all kinds of chemical states, and we only think this is a problem if (1) it gets in the way of communicating with the users, or (2) it affects their ability to actually complete the task. Otherwise, if this is really the way they’d use their computer, we see no reason to exclude them. This is time-aware research at its best, folks.

Inevitably, you’ll encounter users who have an attitude, want to cheat the system, have an axe to grind, or are hostile. We’ve seen every variation of this under the sun. One guy tried to impersonate his son to participate in the study twice; a handful of users have made inelegant passes at our moderators; and then there are profanities, sarcastic put-downs, and deliberate heel-dragging.

Our take on this? The world is what it is; users who are abusive to the moderator, or refuse to follow the basic terms of the study, have no place in your study. We authorize our moderators to terminate sessions immediately if they feel legitimately harassed. If we feel that we were able to get some useful insight from a participant who later becomes abusive, we might feel inclined to offer a partial incentive to the users, proportionate to the length of the terminated session. If we’re not feeling so charitable, we just say:

“I’m sorry, but I don’t think we’ll be able to complete the study without your cooperation. I’m afraid that we won’t be able to offer you the Amazon gift certificate, since, as we mentioned in our recruiting survey, only users who complete the study receive the incentive. Have a good day.”

And good riddance. This approach, of course, should be used only in the direst of circumstances, when it’s unambiguously clear that the participant is a stinker. When the time comes, however, don’t hesitate to drop the hammer.

For some UX veterans (see Andy Budd’s interview in Chapter 1), the notion of talking to users over the phone is appalling. How are you supposed to build empathy with users if you don’t have body language? How can you see what users are thinking if you can’t see their facial expressions? Many practitioners balk at doing remote research for this reason alone. But we’re here to tell you once and for all that there’s nothing wrong with speaking over the phone for most user research. By now most people are perfectly comfortable with expressing themselves over the phone and can adapt their vocal tone to make their emotional cues and meanings understood.

In terms of communicating with the participant, the major difference between in-person and remote testing is that you won’t be able to rely as much on body language as you might normally, for purposes of establishing trust and cutting through conversational tension. This makes the moderator’s responsibilities more complex, since your job isn’t to express yourself naturally, but to encourage users to speak their minds; translating the lab demeanor to the phone just takes some awareness of how to use your voice to moderate.

Take, for example, the habit of “active listening”—the practice of regularly nodding and saying “mm-hmm” to demonstrate that you get what users are saying. In person, nodding your head and repeating “gotcha” may encourage users to keep going, but over the phone, the moderator should cut back on the active listening “uh-huh”s and “gotcha”s because it actually encourages users to wrap up what they’re saying. Don’t be afraid to just sit back and listen—even allow a few awkward silences—to let users gather their thoughts and say everything they have to say.

Related to active listening is “reflecting,” or paraphrasing or repeating things that users have just said to clarify or be sure that you’ve understood their meaning. This technique is somewhat risky for two reasons: (1) it almost always has the same suppressive effect as active listening; and (2) if your paraphrase is inaccurate, it can lead users to agreeing to propositions or coming up with ideas that they may not have otherwise. We’ve found that a better alternative is to begin as if you’re going to paraphrase them but then have them do the bulk of the work by trailing off and letting them fill in their own thoughts, for example.:

Participant: ...and so I decided to click on that link to go to the next page.

Moderator: Okay, so let me get this straight; first, you saw the link, and... what, again?

Participant: I saw the link, and I thought to myself... [paraphrases self]

Since people often paraphrase when repeating what they’ve just said, this strategy achieves the same end as reflecting, with less moderator bias.

Remember that over the phone, all you are is your voice, which means that any emotions you express vocally will have a heavier influence. The big thing to be careful about is staying emotionally on point. If you’re having light banter with participants early in the session, feel free to talk and laugh along with the users; that helps cut down any self-consciousness that may affect their natural behavior. When dealing with users in a study that may be emotionally fraught for whatever reason (as we recently had to, for a study of cancer patients), don’t shy away from expressing polite, sincere sympathy. However, when users get around to discussing anything related to the goals of the study, don’t try to match their enthusiasm or frustration, but instead maintain a friendly, neutral tone. It makes an audible difference if you’re actually feeling comfortable and you’re using your own body language; it’s easier to smile than to try to sound as though you’re smiling.

Ultimately, no matter how much we try to tell you that talking to users over the phone is just as effective and engaged as in-person research, nothing’s going to make the case better than trying it for yourself. You can easily just shrug and wring your hands about how this type of research is not going to work, but don’t hate it until you’ve given it a shot.

Note

ARE YOU GOOD AT MULTITASKING?

You will do a lot of multitasking. Aside from the usual moderator tasks (taking notes, asking questions, referring to the facilitator guide), you’ll also be dividing your attention between IM chat conversations with your observers, which is a substantial attention-sink (see Figure 5-4). If you’re not confident in your ability to multitask, consider easing back on the note taking and simply refer to the session recordings later. Working this way is time consuming but better than getting distracted and spoiling a session.

When all’s said and done, most users care about only two things: how they’ll get paid and how to get the screen sharing stuff off their computer. Wrapping up a study should cover at least these two points, which usually takes no longer than three minutes with the script we gave you in Chapter 2. Very rarely are there any snags in this step; if users have additional questions that you either can’t or don’t have time to answer right away, feel free to tell them that you’ll email them with an answer as soon as possible. And then you’re done. Exhale.

When introducing the study, quickly establish who you are and what the study is about. Then introduce the terms and instructions of the study in small chunks, so the participant doesn’t zone out.

Feel free to go off-script if users do unexpected things relevant to understanding how they use your product, but know how to keep them on track and stay within the allotted time.

You can take timestamped notes more efficiently with jury-rigged spreadsheets and programs; transcription services and voice-to-text software are also options.

Set your observers’ expectations for the session ahead of time and work with them to get their feedback and insight as sessions are ongoing.

You’ll inevitably encounter problem users. Use good moderating skills to deal with quiet, shy, and bored users, decide whether chemically altered users will be viable participants, and politely dismiss rude or uncooperative users.

Don’t worry about not seeing the users’ faces; a lot of expression comes through in vocal tone, and it is behavior you’re most interested in. Adapt your speaking manner to the telephone in order to encourage natural user behavior.