Creating and managing a corporate image

Managing the corporate image is a twofold activity. Firstly, the image needs to be consistent across the organisation. Secondly, it should be possible to maintain the image in the face of outside influences, notably in emergencies and crises.

Creating consistency in the image is dependent on having accurate information about public perception of the organisation and feeding this back to the members of the organisation. Avoidance of multiple images is a concern for many organisations, but in practice the inherent diversity in the workforce makes it difficult to achieve. The most practical approach is probably that of developing a strong corporate culture based around a clear vision statement.

In this theme we explore some of the tools that are available for creating and managing the corporate image and consider the implications of employing an outside agency to help.

You will:

![]() Explore how the corporate image adds to stakeholder value

Explore how the corporate image adds to stakeholder value

![]() Explore the benefits and considerations of sponsorship and word-of-mouth communication as image development techniques

Explore the benefits and considerations of sponsorship and word-of-mouth communication as image development techniques

![]() Identify ways of handling complaints so as to increase customer loyalty

Identify ways of handling complaints so as to increase customer loyalty

![]() Understand the issues surrounding the appointment and control of outside agencies

Understand the issues surrounding the appointment and control of outside agencies

![]() Identify the key factors in choosing an outside agency.

Identify the key factors in choosing an outside agency.

Corporate image and added value

Corporate image is not a luxury. The image of a corporation translates into hard added value for shareholders. This is partly because of the effect that image has on the corporation's customers, but is also a function of the effects it has on staff, and is very much a result of the influence the image has on shareholders. High-profile companies are more attractive to shareholders, even if the company's actual performance in terms of profits and dividends is no better than average. Since the central task of management is to maximise shareholder value, image must be central to management thinking and action.

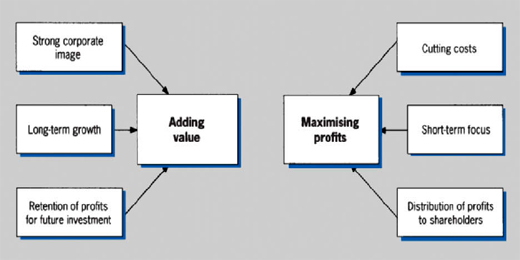

Maximising shareholder value is not the same as maximising profits – see Figure 2.1 for a comparison. Profit maximisation tends to be short-term, a matter of cutting costs, reducing investment, downsizing, increasing sales volumes at the expense of long-term customer loyalty, and so forth. Adding value to the shareholders’ assets is about creating a secure, growing, long-term investment. Since the dot.com bubble burst, investors have become painfully aware that investments in companies with spectacular profits but little underlying solidity is a quick way to lose money. City analysts look more and more towards using measures such as customer loyalty, brand awareness and investment levels when judging the long-term prospects for companies. Taxation structures now discourage speculation on the markets and the increase in the number of small private investors has resulted in much more long-term thinking.

Figure 2.1 Comparison between adding value and maximising profits

The counter-argument to this is that the shifting global marketplace has reduced survival prospects for companies. The life expectancy of a company is now less than 20 years (De Geus, 1997). Maintaining a profitable competitive advantage is also problematic. If a company finds a profitable market niche, competitors respond rapidly and profits fall to the point where it is almost impossible to maintain an adequate return on the original capital investment (Black et al., 1998).

Cable TV

The UK cable TV industry is in trouble. In the 1980s cable was hailed as the future for all forms of communication. E-mail, the Internet, TV and telephone were all promised a golden future. Fibre-optic technology meant that a huge amount of information could be transmitted through cables, and streets were dug up all over Britain to lay cables. Future growth was forecast to be explosive. In Thatcher's Britain the cutting edge of technology promised huge returns for investors.

In the 21st century things look rather different. The investors’ original capital has been sunk (literally) into holes in the ground. Telephone companies such as BT have not been prepared to sit still and let the cable operators steal their markets, nor have satellite TV (and even terrestrial TV) stations been prepared to roll over and play dead. Despite the huge growth in Internet access, which has utilised the cable capacity, competition is so strong that the cable companies are now in serious financial trouble.

For the consumer, this is actually good news. If the cable companies go broke, the liquidators will sell the assets off for a much lower price than the original cost of installing cables. The new operators, freed of servicing the capital, will be able to show a profit – but the original investors will lose out badly.

Obviously some well-established companies have maintained their shareholder value year after year, sometimes by using profits to increase capital value rather than pay dividends. Companies with good reputations are regarded as safe investments because they maintain steady growth, even if the dividends are small. Some investors regard large dividend payouts as a sign that the company is buying shareholder goodwill rather than building the business. However, even blue-chip companies are not immune to environmental shifts.

In recent years, business thinking has become customer orientated, on the basis that pleasing the customers is the best way to get their money from them. In fact, customer orientation does not necessarily mean that the company gives its customers everything they want. It does mean that it ensures that customers are satisfied and loyal in order to maximise the long-term survival potential of the company.

The value that accrues from image management has always been accounted for under the heading of ‘goodwill’ on the company's balance sheet. The goodwill element of the company's value is the difference between the value of its tangible assets and its value on the stock market. For some companies, the value of its goodwill is actually the bulk of its overall value. For example, Coca-Cola's goodwill value is more than 80 per cent of the company's total value. Much of this goodwill value comes from the Coca-Cola brand itself. This approach to valuing a company's reputation and image is now regarded as being somewhat crude, and new measures are being developed to take account of brand value, customer loyalty values, and so forth in order to move away from the reliance on financial measures when assessing a company's success.

Valuing the organisation

Objective

Use this activity to identify the value of your organisation's reputation. The purpose of this exercise is to enable you to evaluate the corporate image-building activities of the organisation, and assess the costs and benefits of these activities. In some cases, these activities will be seen to be of direct cash benefit to the organisation; in others the benefits may well be less clear.

Task

Using an up-to-date edition of the financial press and a copy of the shareholders’ annual report, calculate the stock market valuation of the organisation. This is done by multiplying the number of issued shares by the quoted stock market price for them. You need to take account of other types of shares – preferential shares, non-voting shares and so forth. If you have difficulty with finding out this information, you may be able to ask someone in the finance department of your organisation for help.

Now compare this with the corporate balance sheet, which has a valuation of the organisation's tangible assets. The difference between the two figures is the value of the corporate reputation.

Your calculations: |

|

Is the figure bigger or smaller than the value of the physical assets? Is the figure positive or negative? (It is, of course, possible for an organisation's stock market valuation to be below that of the book value of its assets.)

Feedback

In the vast majority of cases, the stock market value of the organisation is greater than the asset value. If this is not the case, the organisation is likely to be taken over by another organisation and in many cases would be broken up and sold off for its asset value – this is called ‘asset stripping’ and was common practice during the 1970s when inflation was high and profits were low. Some of this extra value is created by intangible assets such as valuable patents or other intellectual property, but much of it is the value of the corporate reputation. Even a fairly casual reading of the financial press will show what the effect of a major scandal is on share prices.

In some cases, the value of the corporate reputation greatly exceeds that of the physical assets, in which case it is obvious that a relatively small investment In corporate reputation building has proved worthwhile. In other cases, it may well be worth considering greater expenditure on reputation building rather than on physical assets – this may be a quicker route to building shareholder value.

Techniques for managing corporate image

Sponsorship

Sponsorship has been defined as:

…an investment, in cash or kind, in an activity in return for access to the exploitable commercial potential associated with this activity.

Source: Meenaghan (1991)

Sponsorship of the arts or sporting events is an increasingly popular way of generating positive feelings about organisations.

Sponsorship in the UK grew a hundredfold between 1970 and 1993, from £4m to £400m. It has continued to grow ever since, with estimates for 2001 ranging between £l,000m and £l,400m. A large part of this increase has come from tobacco firms, due to global restrictions on tobacco advertising. Sponsorship of Formula One motor racing, horse racing, cricket and many arts events such as the Brecon Jazz Festival would be virtually non-existent without the major tobacco companies. Organisations sponsor for a variety of different reasons, as shown in Table 2.1.

Objectives |

96 Agreement |

Rank |

Press coverage/exposure/opportunity |

84.6 |

1 |

TV coverage/exposure/opportunity |

78.5 |

2 |

Promote brand awareness |

78.4 |

3 |

Promote corporate image |

77.0 |

4 |

Radio coverage/exposure/opportunity |

72.3 |

5 |

Increase sales |

63.1 |

6 |

Enhance community relations |

55.4 |

7 |

Entertain clients |

43.1 |

8 |

Benefit employees |

36.9 |

9 |

Match competition |

30.8 |

10 |

Fad/fashion |

26.2 |

11 |

Table 2.1 Reasons for sponsorship Source: Zafer Erdogan and Kitchen (1998)

The basis of sponsorship is to take customers’ beliefs about the sponsored event and link them to the organisation doing the sponsoring. Thus an organisation wishing to appear middle-class and respectable might sponsor a theatre production or an opera, whereas an organisation wishing to appear to be ‘one of the lads’ might sponsor a football team. As far as possible, sponsorship should relate to the organisation's existing image.

Sponsorship will only work if it is linked to other marketing activities, in particular to advertising. Hefler (1994) estimates that two to three times the cost of sponsorship needs to be spent on advertising if the exercise is to be effective. The advertising should tell customers why the organisation has chosen this particular event to sponsor so that the link between the organisation's values and the sponsored event is clear. A bank which claims to be ‘Proud to sponsor the Opera Festival’ will not do as well as it would if it were to say: ‘We believe in helping you to enjoy the good things in life – that's why we sponsor the Opera Festival’. A recent development in sponsorship is to go beyond the mere exchange of money as the sole benefit to the sponsored organisation or event. If the sponsored organisation can gain something tangible in terms of extra business or extra publicity for its cause, then so much the better for both parties.

Lincoln and Cirque du Soleil

Lincoln-Mercury (a Ford subsidiary) sponsored a mini-tour of the Canadian circus company, Cirque du Soleil. The tour was linked to the new model of the Lincoln luxury car, but Cirque du Soleil was able to use the mini-tour as a publicity exercise for its later major tour of the United States. This in turn led to more publicity for Lincoln, so the two organisations developed a symbiotic relationship (beneficial to both).

There is evidence that consumers feel gratitude towards the sponsors of their favourite events, although of course this may be an emotional linking of the sponsor and the event rather than a feeling of gratitude that the sponsor made the event possible. The difference between these emotions is academic in any case – if sponsorship leads to an improvement in the organisation's standing with customers, that should be sufficient. There are also spin-offs for the internal PR of the organisation: most employees like to feel that they are working for a caring organisation, and sponsorship money often leads to free tickets or price reductions for staff of the sponsoring organisation.

The following criteria apply when considering sponsorship (Hefler, 1994):

![]() The sponsorship must be economically viable – i.e. it should be cost-effective

The sponsorship must be economically viable – i.e. it should be cost-effective

![]() The event or organisation being sponsored should be consistent with the brand image and overall marketing communications plans

The event or organisation being sponsored should be consistent with the brand image and overall marketing communications plans

![]() It should offer a strong possibility of reaching the desired target audience

It should offer a strong possibility of reaching the desired target audience

![]() Care should be taken if the event has been sponsored before: the audience may confuse the sponsors, and you may be benefiting the earlier sponsor.

Care should be taken if the event has been sponsored before: the audience may confuse the sponsors, and you may be benefiting the earlier sponsor.

Another recent development in sponsorship is ambush marketing. This is the practice of linking one's product to a sponsored event without actually sponsoring anything. For example, during the 1998 FIFA World Cup soccer tournament, some companies ran World Cup competitions or World Cup promotions without actually contributing anything to the event. There is very little that can be done to prevent this, although sponsoring companies can console themselves with the thought that the TV cameras at the event itself will focus on their company names, not on those of the ambush marketers.

Word of mouth

People often discuss products. We like to talk about the things we have bought, the films we have seen and the holidays we have been on or are about to go on. We like to ask our friends’ opinions and to air our own. This type of communication is extremely powerful as a marketing tool, but it is also difficult to control.

The main advantage of word-of-mouth communication is that it comes from a reliable source. People tend to trust the word of their friends and acquaintances much more than they do advertising. This is perhaps a little strange considering that advertisers are constrained by law to be legal, decent, honest and truthful. Few people can say that about their friends.

Another advantage is that word-of-mouth communication is interactive. It allows for discussion and for asking questions if a particular aspect of the communication is unclear.

The main disadvantage of word of mouth is that it is difficult to control. The evidence is that bad news travels twice as fast as good news, and that most word of mouth is actually negative.

Word of mouth can be encouraged and, to an extent, directed by the following means:

![]() Press releases News stories about the organisation will generate discussion, to a greater or lesser extent.

Press releases News stories about the organisation will generate discussion, to a greater or lesser extent.

![]() Bring-a-friend schemes In such a scheme, a reward is given for recruiting a friend. Since some people feel uncomfortable about being rewarded for recommending a friend to do something, the reward is often given to the friend instead. The Dutch railway system, Nederlands Spoorweg, ran a very successful campaign to recruit more people to its senior citizens’ railcard. The company simply sent out packs containing trial-period railcards to its retired workers asking them to pass these on to their friends.

Bring-a-friend schemes In such a scheme, a reward is given for recruiting a friend. Since some people feel uncomfortable about being rewarded for recommending a friend to do something, the reward is often given to the friend instead. The Dutch railway system, Nederlands Spoorweg, ran a very successful campaign to recruit more people to its senior citizens’ railcard. The company simply sent out packs containing trial-period railcards to its retired workers asking them to pass these on to their friends.

![]() Awards and certificates Trophies, certificates and awards are often displayed or at least talked about. The Blood Transfusion Service uses this to good effect by giving donors awards for giving 10 pints, 20 pints, and so forth.

Awards and certificates Trophies, certificates and awards are often displayed or at least talked about. The Blood Transfusion Service uses this to good effect by giving donors awards for giving 10 pints, 20 pints, and so forth.

Some people are more useful than others in terms of word-of-mouth communication because they are more influential. Identifying these influential people is not easy, but some general principles have been established.

Firstly, demography has very little influence for most products. Although age might have some bearing on, say, purchase of trainers, it is far from being the most influential factor. Social activity shows a better correlation, since opinion leaders and influencers are usually gregarious. Typically, influencers are positive towards new ideas and are innovative. This is not surprising, since in order to recommend a product one might assume that the individual will have tried it, read about it or taken some interest in it. There is a low correlation between personality characteristics and opinion leadership, but influencers are more interested in the product area than other people. This means that someone might be an influencer for one product category and not for another – again, not surprising. One might consult a computer enthusiast about computers, but not expect the same person to be able to advise about musical instruments.

In view of the fact that most word of mouth is negative, managers might be better employed in trying to prevent dissatisfied customers from voicing their complaints to others.

Three basic types of complaining behaviour have been identified (Singh, 1988): voiced response, in which the customer comes back and complains to the supplier; third-party response, in which the customer enlists the aid of lawyers, consumer organisations, trading standards officers, and so forth; and private response, in which the customer complains to friends. These are summarised in Table 2.2. Customers who come back with a complaint actually give the organisation a chance to put things right before they move on to one of the other two options, so complaints should really be encouraged whenever possible. This is why waiters always ask if the meal is all right – waiting until the food has been eaten or until a complaint has been made is probably counterproductive.

Voiced response |

The customer comes back to complain. This is actually the best type of response from the supplier's viewpoint because it offers an opportunity to rescue the situation |

Third-party response |

The customer enlists the aid of a bigger, more powerful ally such as a lawyer or a consumer protection organisation |

Private response |

The customer tells everybody else about the problem. This could well be the worst outcome for the supplier |

Table 2.2 Types of complaining behaviour

In the case of a physical product, simple replacement of the faulty item is the usual remedy for a complaint. In service industries, the situation is more complex because services are difficult to replace. In general, services fall into three categories as regards redress for complaints (Blythe, 1997):

1 Services where it is appropriate to offer a repeat service or a voucher – dry cleaning, domestic appliance repairs and takeaway food are examples.

2 Services where a refund is sufficient – retail shops, cinemas and theatres, and video rental shops are examples.

3 Services where consequential losses might have to be compensated for – examples are legal services, medical services and hairdressers.

The key factors in deciding how to handle the complaint are the strength of the complaint, the degree of blame attaching to the supplier (from the customer's viewpoint) and the legal and moral relationship between the supplier and the consumer. Failure to handle complaints will almost certainly lead to damage to the organisation's reputation. Research shows, on the other hand, that customers whose complaints are handled to their satisfaction are likely to become even more loyal than those who had no complaint to begin with. This is logical. People understand that things go wrong occasionally, but knowing that they are dealing with an organisation that will put things right is reassuring.

Handling complaints

Objective

Use this activity to assess the complaint-handling behaviour in your organisation. The objective of this activity is to identify ways in which the complaint-handling procedures can be used to add value to the corporate reputation. You should also be able to use the activity to consider where improvements might be made in the complaint-handling procedure.

Task

Examine records of complaints made to your organisation in recent months. These may be in the form of letters, e-mails, telephone conversations, letters from lawyers, reports on consumer affairs programmes, or complaints from trade or consumer protection bodies on behalf of customers.

Using the table provided, list the complaints under each category, and record what happened next in terms of complaint handling.

Complainant |

Voiced complaint |

Third-party complaint |

What happened next? |

|

|

|

|

Complainant |

Voiced complaint |

Third-party complaint |

What happened next? |

|

|

|

|

Feedback

It may be that some complaints feature more than once in the list; for example, someone who voiced a complaint but was dissatisfied with the result might well complain again, or bring a third party to bear on the issue.

On the positive side, you may have found that the final column contains occasional feedback from the customer or stakeholder to the effect that the complaint has been handled satisfactorily. The danger signal would be if the complaint had been treated dismissively by the organisation and nothing has been heard from the customer since.

The question here is what can be done about this? You might want to consider ways of improving the feedback from complaining customers to ensure that they are completely happy with the outcome. You might also be able to identify trends in the complaining behaviour – this might also give clues as to what can be done.

Using outside agencies to build

corporate image

Outside public relations agencies are frequently used for developing corporate image. The reasons for doing this might be that:

![]() the organisation is too small to warrant having a specialist PR department

the organisation is too small to warrant having a specialist PR department

![]() external agencies have expertise which the organisation lacks

external agencies have expertise which the organisation lacks

![]() the external agency can provide an unbiased view of the organisation's needs

the external agency can provide an unbiased view of the organisation's needs

![]() external agencies often carry greater credibility than internal departments or managers

external agencies often carry greater credibility than internal departments or managers

![]() economies of scale may make the external agency cheaper to use

economies of scale may make the external agency cheaper to use

![]() one-off events or campaigns can be more efficiently run by outsiders and the organisation's attention is not deflected from its core activities.

one-off events or campaigns can be more efficiently run by outsiders and the organisation's attention is not deflected from its core activities.

What an outside agency might do

The Public Relations Consultants’ Association lists the following activities as services that a consultancy might offer:

![]() establishing channels of communication with the client's public or publics

establishing channels of communication with the client's public or publics

![]() management communications

management communications

![]() marketing and sales promotion-related activity

marketing and sales promotion-related activity

![]() advice or services relating to political, governmental or public affairs

advice or services relating to political, governmental or public affairs

![]() financial public relations, dealing with shareholders and investment tipsters

financial public relations, dealing with shareholders and investment tipsters

![]() personnel and industrial relations advice

personnel and industrial relations advice

![]() recruitment, training, and higher and technical education.

recruitment, training, and higher and technical education.

Source: Public Relations Consultants’ Association

This list is not exhaustive. Since outside agencies often specialise, an organisation may need to go to several different sources to access all the services listed above. Even organisations with an in-house public relations department may prefer to subcontract some specialist or one-off activities. Some activities which may involve an outside agency are:

![]() Exhibitions The infrequency of attendance at exhibitions, for most organisations, means that in-house planning is likely to be disruptive and inefficient. Outside consultants may set up four or five exhibitions a week, compared with the average organisation's four or five a year, so they will have strong expertise in exhibition management.

Exhibitions The infrequency of attendance at exhibitions, for most organisations, means that in-house planning is likely to be disruptive and inefficient. Outside consultants may set up four or five exhibitions a week, compared with the average organisation's four or five a year, so they will have strong expertise in exhibition management.

![]() Sponsorship Outside consultants will have contacts and negotiating expertise which is unlikely to be available in-house. In particular, an outside agency will have up-to-date knowledge of what the ‘going rate’ is for sponsoring particular events and individuals.

Sponsorship Outside consultants will have contacts and negotiating expertise which is unlikely to be available in-house. In particular, an outside agency will have up-to-date knowledge of what the ‘going rate’ is for sponsoring particular events and individuals.

![]() Production of house journals Because of the economies of scale available in the printing and publishing industry, house journals can often be produced more cheaply by outsiders than by the organisation itself.

Production of house journals Because of the economies of scale available in the printing and publishing industry, house journals can often be produced more cheaply by outsiders than by the organisation itself.

![]() Corporate or financial PR Corporate PR relies heavily on having a suitable network of contacts in the finance industry and the financial press. It is extremely unlikely that an organisation's PR department will have a comprehensive list of such contacts, so the outside agency provides an instant network of useful contacts.

Corporate or financial PR Corporate PR relies heavily on having a suitable network of contacts in the finance industry and the financial press. It is extremely unlikely that an organisation's PR department will have a comprehensive list of such contacts, so the outside agency provides an instant network of useful contacts.

![]() Parliamentary liaison Lobbying MPs is an extremely specialised area of public relations, requiring considerable insider knowledge and an understanding of current political issues. Professional lobbyists are far better able to carry out this work than an organisation's own public relations officer.

Parliamentary liaison Lobbying MPs is an extremely specialised area of public relations, requiring considerable insider knowledge and an understanding of current political issues. Professional lobbyists are far better able to carry out this work than an organisation's own public relations officer.

![]() Organising one-off events Like exhibitions, one-off events are almost certainly better subcontracted to an outside agency.

Organising one-off events Like exhibitions, one-off events are almost certainly better subcontracted to an outside agency.

![]() Overseas PR Organisations are extremely unlikely to have the specialist local knowledge necessary for setting up public relations activities in a foreign country.

Overseas PR Organisations are extremely unlikely to have the specialist local knowledge necessary for setting up public relations activities in a foreign country.

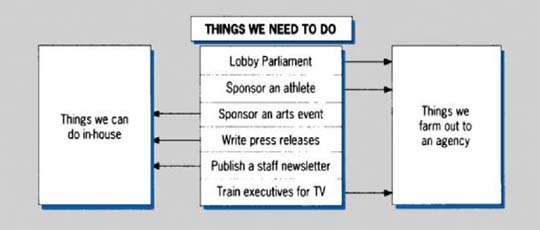

You can decide which tasks the agency should carry out for you by a process of elimination. Begin by deciding which tasks you are able to carry out in-house, and then whatever tasks are left can be contracted out to the agency – see Figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2 Deciding which tasks to contract out

Choosing an appropriate agency or consultancy begins with looking at the agency's ability to carry out the specific tasks you need. Table 2.3 shows some of the trade-offs involved in choosing a PR consultancy.

Characteristic |

Considerations to be made |

Years in business |

A long-established consultancy is likely to be experienced and reliable: on the other hand, it may be lacking in new ideas |

Size |

A large consultancy may have a wide range of services to offer, but may not be interested in a small account |

Full service or specialist? |

Specialists get very good at one thing: full-service agencies offer a one-stop-shop which helps in co-ordinating activities |

Degree of fit with client company |

Is the client company local, national or international? Does the agency have experience of other firms in the same business? |

Client list |

Are there conflicts of interest? Does the consultancy lose a lot of clients? Who are the existing clients? |

Staff |

How experienced and qualified are the staff who will work on your account? What other accounts will they handle? What is the staff turnover at the consultancy? |

Results |

Does the consultancy understand what you need? How will results be measured and reported? What will it cost – and on what basis will payment be made? |

Table 2.3 Choosing a PR consultancy

Unless the outside agency has been called in as a result of a sudden crisis, which is possibly the worst way to handle both PR and consultants, the consultancy will be asked to present a proposal. This allows the consultancy time to research the client's situation and its existing relationships with its publics. The proposal should contain comments on the following aspects of the task:

![]() analysis of the problems and opportunities facing the client organisation

analysis of the problems and opportunities facing the client organisation

![]() analysis of the potential harm or gain to the client

analysis of the potential harm or gain to the client

![]() analysis of the potential difficulties and opportunities presented by the case, and the various courses of action (or inaction) which would lead to those outcomes

analysis of the potential difficulties and opportunities presented by the case, and the various courses of action (or inaction) which would lead to those outcomes

![]() the overall programme goals and the objectives for each of the target publics

the overall programme goals and the objectives for each of the target publics

![]() analysis of any immediate action needed

analysis of any immediate action needed

![]() long-range planning for achieving the objectives

long-range planning for achieving the objectives

![]() monitoring systems for checking the outcomes

monitoring systems for checking the outcomes

![]() staffing and budgets required for the programme.

staffing and budgets required for the programme.

Client organisations will often ask several agencies to present, with the aim of choosing the best among them. This approach can cause problems, for several reasons. Firstly, the best agencies may not want to enter into a competitive tendering situation. Secondly, some agencies will send their best people to present, but will actually give the work to their more junior staff. Thirdly, agencies may not want to present their best ideas, feeling (rightly in some cases) that the prospective client will steal their ideas. Finally, it is known that some clients will invite presentations from agencies in order to keep their existing agency on its toes. Such practices are ethically dubious and do no good for the client organisation's reputation. Since the whole purpose of the exercise is to improve the organisation's reputation, annoying the PR agencies is clearly not an intelligent move. To counter the possibility of potential clients stealing their ideas, some of the leading agencies now charge a fee for bidding.

Relationships with external PR consultancies tend to last. Some major organisations have used the same PR consultants for over 20 years. Frequently changing consultants is not a good idea. Consultants need time to build up knowledge of the organisation and its personnel, and the organisation needs time to develop a suitable atmosphere of trust. The consultancy needs to be aware of sensitive information if it is not to be taken by surprise in a crisis, and the client organisation is unlikely to feel comfortable with this unless the relationship has been established for some time.

Developing a brief

The purpose of the brief is to bridge the gap between what the client needs and what the consultant is able to supply. Without a clear brief, the consultant has no blueprint to follow, and neither party has any way of knowing whether the exercise has been successful or not.

Developing a brief begins with the organisation's objectives. Objective setting is a strategic decision area, so it is likely to be the province of senior management. Each objective needs to meet SMARTT criteria:

![]() Specific – in other words, it must relate to a narrow range of outcomes

Specific – in other words, it must relate to a narrow range of outcomes

![]() Measurable – if it is not measurable, it is merely an aim

Measurable – if it is not measurable, it is merely an aim

![]() Achievable – there is no point in setting objectives which cannot be achieved or which are unlikely to be achieved

Achievable – there is no point in setting objectives which cannot be achieved or which are unlikely to be achieved

![]() Relevant to the organisation's situation and resources

Relevant to the organisation's situation and resources

![]() Targeted accurately

Targeted accurately

![]() Timed – a deadline should be in place for its achievement.

Timed – a deadline should be in place for its achievement.

The objectives will dictate the budget if the organisation is using the objective-and-task method of budgeting. This method means deciding what tasks need to be undertaken to achieve the final outcome and working out how much it will cost to achieve each task. Most organisations tend to operate on the all-we-can-afford budgeting method, which involves agreeing a figure with the finance director. In these circumstances, the SMARTT formula implies that the budget will dictate the objectives since the objectives must be achievable within the available resources.

Setting the objectives is, of course, only the starting point. Objectives need to be translated into tactical methods for their achievement, and these tactics also need to be considered in the light of what the organisation is trying to achieve.

The brief will be fine-tuned in consultation with the PR agency. From the position of its specialist knowledge, the agency will be able to say whether the budget is adequate for what needs to be achieved or, conversely, say whether the objectives can be achieved within the budget on offer. The agency can also advise on what the appropriate objectives should be, given the organisation's current situation.

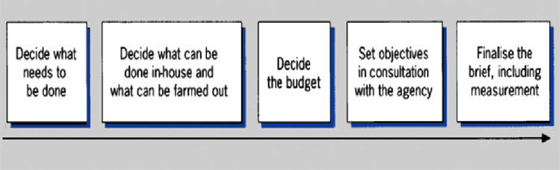

Figure 2.3 outlines the process of establishing a brief.

Figure 2.3 Establishing a brief

Measuring outcomes

If the outcomes from the PR activities do not match up with the budgeted objectives, conflict between the client and the agency is likely to result. The most common reason for the relationship breaking down is conflict over the costs and hours billed compared with the outcomes achieved. From the agency's viewpoint, much of what happens is outside its direct control. Sponsored events might not attract sufficient audiences, press releases might be spiked as a result of major news stories breaking and special events might be rained off. Many a carefully planned, reputation-enhancing exercise has foundered when the celebrity athlete involved has been caught taking drugs, for example.

Measuring outcomes needs to be considered at the objective-setting stage. A good PR agency will not offer any guarantees of outcomes, but it should be feasible to assign probabilities to the outcomes and to put systems in place for assessing whether the objectives were achieved.

Table 2.4 gives some examples of evaluation methods for PR activities. This list is by no means comprehensive, of course.

Activity |

Possible evaluation methods |

Press campaign to raise awareness |

Formal market research to determine public awareness of the brand/organisation |

Campaign to improve the public image |

Formal market research:

|

Exhibition or trade show |

Records of contacts made, tracking of leads, formal research to determine improvements in image |

Sponsorship of a sporting event |

Recall rates for the sponsorship activity |

Table 2.4 PR evaluation methods

Although market research is a complex topic which is outside the scope of this book, it is possible to identify the stages in the process of measuring PR outcomes. An outline of the approach has been provided by Rossi and Freeman (1999), which is shown in Table 2.5.

Programme conceptualisation and design |

What is the extent and distribution of the target problem and/or population? Is the programme designed in conformity with intended goals. Is there a coherentrationale underlying it, and have chances of successful delivery been maximised? What are project or existing costs, and what is their relation to benefits and effectiveness? |

Monitoring and accountability of programme implementation |

Is the programme reaching the specified population or target area? Are the intervention efforts being conducted as specified in the programme design? |

Assessment of programme utility, impact and efficiency |

Is the programme effective in achieving its intended goals? Can the results of the programme be explained by some alternative process that does not include the programme? Is the programme having some effects that were not intended? What are the costs to deliver services and benefits to programme participants? Is the programme an efficient use of resources compared with alternative uses of the resources? |

Table 2.5 The evaluation research process Source: Rossi and Freeman (1999)

If these questions are answered in the negative, questions should be asked either about the realism of the objectives or about the tactics the agency has used. If everything goes wrong, it is tempting to fire the agency and try another firm, but in practice this may not be the best answer. Both agency and client will have learned from the experience, possibly at some expense, and it is probably better to stay together and learn the lesson than to split up and have to ride the learning curve all over again with another agency.

Deciding whether to use an agency

Objective

Use this activity to decide whether your organisation should use an agency for some (or all) of its corporate reputation activities. The purpose of the exercise is to assess whether it might be either cheaper or more effective to use an agency rather than carry out the same activities in-house. You might also be able to identify areas in which an agency would be able to carry out a task which is currently not being undertaken at all – in other words, a task which would benefit the organisation but which is currently being ignored for whatever reason.

Task

Using the framework provided below, list the reputation management activities which you believe your organisation is carrying out or should carry out.

In the next column, list the resources necessary to accomplish the task.

In the next column, list the resources which you have available for completing the task.

The final column should contain a list of resources which are needed but which are not available. The question is, should you find a way to provide these resources in-house, or should you farm the activity out to an agency?

Activity |

Resources needed |

Resources available |

Resource shortfall |

|

|

|

|

Feedback

There is almost always a resources shortfall, even for those activities which are already carried out in-house. This makes the decision difficult as to whether it would be more efficient to use an agency.

The decision ultimately rests on whether the expected returns in terms of improved corporate reputation justify the extra outlay (if any) in hiring an agency. This decision in turn rests on whether the outlay will be large or small in relation to the improvements which using an agency will bring.

Recap

Recap

Explore how the corporate image adds to stakeholder value

The corporate image should add value to the stakeholders’ assets by creating a secure, growing, long-term investment, rather than a short-term gain.

The value that accrues from image management is accounted for as ‘goodwill’ on the balance sheet. The goodwill element of a company's value is the difference between the value of its tangible assets and its value on the stock market.

Explore the benefits and considerations of sponsorship and word-of-mouth communication as image development techniques

Sponsorship works by transferring the positive feeling that a customer has for the sponsored event to the sponsor organisation. The event or organisation being sponsored should be consistent with the sponsor's brand image and offer a strong possibility of reaching the desired target audience.

People trust word-of-mouth communication, especially from people that they regard as opinion leaders or as knowledgeable about a particular product. However, word-of-mouth communication is difficult to control and can be negative.

Organisations use press releases, bring-a-friend schemes, and awards and certificates to encourage positive word-of-mouth communication.

Identify ways of handling complaints so as to increase customer loyalty

There are three types of complaining behaviour: voiced response, third-party response and private response.

![]() Redress is usually provided as a replacement product or repeat service, refund or voucher and, in some cases, compensation for consequential losses.

Redress is usually provided as a replacement product or repeat service, refund or voucher and, in some cases, compensation for consequential losses.

![]() The key factors influencing how to handle a complaint are the strength of the complaint, the degree of blame attaching to the supplier and the legal and moral relationship between the customer and supplier.

The key factors influencing how to handle a complaint are the strength of the complaint, the degree of blame attaching to the supplier and the legal and moral relationship between the customer and supplier.

Understand the issues surrounding the appointment and control of outside agencies

![]() Consultancies and agencies exist for two reasons: firstly, to carry out activities for which the organisation does not have resources, and, secondly, to carry out activities which, because of its specialist expertise, it can do better than the organisation.

Consultancies and agencies exist for two reasons: firstly, to carry out activities for which the organisation does not have resources, and, secondly, to carry out activities which, because of its specialist expertise, it can do better than the organisation.

![]() External agencies take time to build up their knowledge of your organisation so be prepared to invest more time at the start of your relationship. Create a brief with SMARTT objectives and put in place an evaluation process to measure whether these have been achieved.

External agencies take time to build up their knowledge of your organisation so be prepared to invest more time at the start of your relationship. Create a brief with SMARTT objectives and put in place an evaluation process to measure whether these have been achieved.

Identify the key factors in choosing an outside agency

![]() These factors include length of time in the business, size, full service or specialist, degree of fit with your organisation, its client list, calibre of staff and how well it understands the results that you need.

These factors include length of time in the business, size, full service or specialist, degree of fit with your organisation, its client list, calibre of staff and how well it understands the results that you need.

More @

More @

Balmer, J. and Greyser, S. (eds) (2003) Revealing the Corporation: Perspectives on Identity, Image, Reputation and Corporate Branding, Routledge

The book draws on articles from leading journals in the field and includes important recent articles as well as classics, written by recognised masters of the genre, which still inform current debate and practice.

Schultz, M., Hatch, M. and Larsen M. H. (2000) The Expressive Organization: Linking Identity, Reputation and the Corporate Brand, Oxford University Press

According to the authors, the future lies with ‘the expressive organization’. Such organisations not only understand their distinct identity and their brands, but are also able to express these externally and internally.

www.sponsorship.com There are a number of interesting resources at the IEG Inc. site, including a good Learn About Sponsorship section, a news section and even job information. Some areas require registration.

Find comprehensive best practice guides on finding an external communications partner and on the construction of a brief at the website for the Public Relations Consultants’ Association, www.prca.org.uk/sites/prca.nsf/homepages/homepage. These free guides are downloadable.