Managing the external image

This theme explores how an organisation can manage its image with the outside world.

In the days of instant messaging, instant access, and 24/7 news cycles, strong, professionally run public relations operations are critical to the success of the most successful organisations.

You start by considering the strategic role of public relations in influencing how the public views your organisation.

You then go on to explore the topic of corporate governance and how ethical behaviour and meeting legal responsibilities play an increasing part in the creation and destruction of corporate image and reputation.

Next to doing the right thing, the most important thing is to let people know you are doing the right thing.

John D. Rockefeller

Oil magnate and

philanthropist,

(1839–1937)

Organisations face crises all the time – product recalls, plant closures, a crime committed by an employee, a company leader making a poor personal decision. The fact that we only hear a selection of stories of this kind in the media illustrates the power of effective crisis communications. In the final part of this book you look at what organisations can do to protect their reputation and image when things go wrong.

You will:

![]() Consider how public relations activities help in generating and managing reputation

Consider how public relations activities help in generating and managing reputation

![]() Assess the effectiveness of your organisation's press releases

Assess the effectiveness of your organisation's press releases

![]() Understand the ethical problems that inform good corporate citizenship and explore ways to improve the ethical stance of the organisation

Understand the ethical problems that inform good corporate citizenship and explore ways to improve the ethical stance of the organisation

![]() Identify how you can protect your organisation's image and reputation in the event of a corporate crisis.

Identify how you can protect your organisation's image and reputation in the event of a corporate crisis.

Public relations and external communication

Public relations or PR is the management of corporate reputation through the management of relationships with the organisation's publics. Roger Haywood (1998) offers an alternative definition:

…those efforts used by management to identify and close any gap between how the organisation is seen by its key publics and how it would like to be seen.

What public relations does

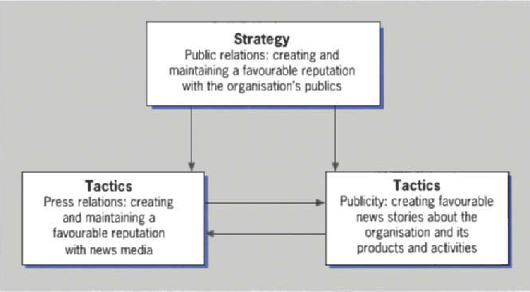

PR has more than just a role in defending the organisation from attack and publicising its successes. It has a key role in relationship marketing, since it is concerned with building a long-term reputation rather than gaining a quick sale. There is a strategic relationship between publicity, PR and press relations. PR occupies the overall strategic role in the relationship, as shown in Figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1 Publicity, PR and press relations

In some cases, organisations use PR solely for crisis management, either by employing somebody with a nice smile and a friendly voice to handle complaints or by waiting for things to go wrong and then beginning to formulate a plan for handling the problem. This is a firefighting, or reactive, approach to public relations, and is generally regarded as being far less effective than a proactive approach, which seeks to avoid problems arising.

What do public relations managers do?

PR managers have the task of co-ordinating all those activities which make up the public face of the organisation and will have some or all of the following tasks to handle:

![]() organising press conferences

organising press conferences

![]() organising staff training workshops

organising staff training workshops

![]() organising social events

organising social events

![]() handling incoming complaints or criticism

handling incoming complaints or criticism

![]() grooming senior management for TV or press interviews

grooming senior management for TV or press interviews

![]() moulding the internal culture of the organisation.

moulding the internal culture of the organisation.

PR people talk about ‘publics’ rather than ‘the public’. This is because they deal with a wide range of people, all with different needs and preconceptions.

Dealing with the following publics may be part of the PR manager's remit:

![]() customers

customers

![]() suppliers

suppliers

![]() staff

staff

![]() government and government departments

government and government departments

![]() local government

local government

![]() neighbours

neighbours

![]() local residents

local residents

![]() the general public

the general public

![]() pressure groups such as environmentalists or trade unions

pressure groups such as environmentalists or trade unions

![]() other industry members.

other industry members.

In each case the approach will be different and the expected outcomes will also be different. The basic routes by which PR operates are word of mouth, press and TV news stories, and personal recommendation. The aim of good PR is to put the name of the organisation and its products and services into people's minds in a positive way.

PR is not advertising because the organisation does not directly pay for it. Also, advertising can be both informative and persuasive, but PR can only be used for conveying information or for placing the organisation in the public eye in a positive way. PR does not generate business directly, but achieves the organisation's long-term objectives by creating positive feelings. The ideal is to give the world the impression that this is ‘a good firm to do business with’.

Tools of public relations

PR people use a number of different ways to achieve their aims. The list in Table 5.1 is by no means comprehensive, but does cover the main tools available to PR managers.

Tool |

Description and examples |

Press releases |

A press release is a news story about the organisation, usually designed to present the organisation in a good light but often intended just to keep it in the public eye. For example, a company might issue a press release about opening a new factory in a depressed area of the country; newspapers print this as news, since it is about creating jobs |

Sponsorship |

Sponsorship of events, individuals or organisations is useful for creating favourable publicity. For example, Mars sponsored the London Marathon for many years, gaining two or three hours of TV exposure for the brand in exchange for a relatively small outlay |

Publicity stunts |

Sometimes organisations will stage an event specifically for the purpose of creating a news story. For example, a taxi firm might take a group of deprived children for a day at the seaside, using the firm's cars; this might be sufficiently newsworthy to make the local TV news |

Word of mouth |

Generating favourable word of mouth is an important aim of PR. For example, Body Shop requires all its franchises to carry out some project to benefit their local community. Inevitably this generates favourable attitudes locally, which enhances Body Shop's reputation as a good corporate citizen |

Corporate advertising |

Corporate advertising is aimed at improving the corporate image rather than selling products. Examples are the Christmas greetings advertisements put out by major companies such as BT or Tesco on Christmas Day |

Lobbying |

Lobbying is the process of making representations to members of Parliament or other politicians. For example, an industry association might lobby MPs to persuade Parliament not to introduce new restrictions on its industry |

Of these, the press release and sponsorship are probably the most important.

A press release is a favourable news story about the organisation that originates from within the organisation itself. Newspapers and magazines earn their money mainly through paid advertising, but they attract readers by having stimulating articles about topics of interest to the readership. Editors need to fill space and are quite happy to use a press release to do so if the story is newsworthy and interesting to the readership. Some magazines and newspapers would find it difficult to function without press releases, since they do not have a large enough reporting staff to write all the content.

The advantages of writing a press release are that it is much more credible than an advertisement, it is much more likely to be read and the space within the publication is free. There are, of course, costs attached to producing press releases.

Table 5.2 shows the criteria under which the press stories must be produced if they are to be published. Increasing consumer scepticism and resistance to advertising has meant that there has been a substantial growth in the use of press releases and publicity in recent years. Press stories are much more credible, and although they do not usually generate business directly, they do have a positive long-term effect in building brand awareness and loyalty.

Criterion |

Example |

Stories must be newsworthy, i.e. of interest to the reader |

Articles about your new lower prices are not newsworthy; articles about opening a new factory creating 200 jobs are |

Stories must not be merely thinly disguised advertisements |

A story saying that your new computer package is great value at only £799 would not be published; a story saying that you were sponsoring a computer literacy campaign in a deprived area would stand a much better chance |

Stories must fit the editorial style of the magazine or newspaper to which they are sent |

An article sent to Cosmopolitan magazine about your new sports car would probably not be published; an article about your new female marketing director probably would |

Table 5.2 Criteria for successful press releases

Editors do not have to publish press releases exactly as they are received. They reserve the right to alter stories, add to them, comment on them or otherwise change them around to suit their own purposes. For example, a press release about your company's new computer game might turn into part of an article about the damage computer gaming is doing to the nation's youth. There is nothing substantial that press officers can do about this. Cultivating a good relationship with the media is therefore an important part of the press officer's job.

Sometimes this will involve business entertaining, but more often the press officer will simply try to see to it that the job of the press is made as easy as possible. This means supplying accurate and complete information, writing press releases so that they require a minimum of editing and rewriting, and making the appropriate corporate spokesperson available when required.

When business entertaining is appropriate, it will often come as part of a media event or press conference. This may be called to launch a new product, to announce some major corporate development such as a merger or takeover or (less often) when there has been a corporate crisis. This will involve inviting journalists from the appropriate media, serving refreshments and providing corporate spokespeople to answer questions and make statements. This kind of event will have limited success, however, unless the groundwork for it has been thoroughly laid.

Journalists are often suspicious of media events, sometimes feeling that the organisers are trying to buy them off with a buffet and a glass of wine. This means they may not respond positively to the message the PR people are trying to convey, and may write a critical article rather than the positive one that had been hoped for.

To minimise the chance of this happening, media events should follow these basic rules:

![]() Avoid calling a media event or press conference unless you are announcing something that the press will find interesting

Avoid calling a media event or press conference unless you are announcing something that the press will find interesting

![]() Check that there are no negative connotations in what you are announcing

Check that there are no negative connotations in what you are announcing

![]() Ensure that you have some of the organisation's senior executives there to talk to the press, not just the PR people

Ensure that you have some of the organisation's senior executives there to talk to the press, not just the PR people

![]() Only invite journalists with whom you feel you have a good working relationship

Only invite journalists with whom you feel you have a good working relationship

![]() Avoid being too lavish with the refreshments

Avoid being too lavish with the refreshments

![]() Ensure that your senior executives, in fact anybody who is going to speak to the press, has had some training for this – this is particularly important for TV

Ensure that your senior executives, in fact anybody who is going to speak to the press, has had some training for this – this is particularly important for TV

![]() Be prepared to answer all questions truthfully – journalists are trained to spot lies and evasions

Be prepared to answer all questions truthfully – journalists are trained to spot lies and evasions

![]() Take account of the fact that newspapers and the broadcast media have deadlines to which they must adhere – call the conference at a time that will allow reporters enough time to file their stories.

Take account of the fact that newspapers and the broadcast media have deadlines to which they must adhere – call the conference at a time that will allow reporters enough time to file their stories.

From the press viewpoint, it is always better to speak to the most senior managers available rather than to the PR people. Having said that, senior managers will need some training in handling the press and answering questions, and also need to be fully briefed on anything the press might want to ask. In the case of a press conference called as a result of a crisis, this can be a problem. Many major organisations establish crisis teams of appropriate senior managers who are available and prepared to comment should the need arise. Press officers should be prepared to handle queries from journalists promptly, honestly and enthusiastically, and to arrange interviews with senior personnel if necessary.

Press release

Objective

Use this activity to assess the effectiveness of your organisation's press releases. The purpose of this exercise is to enable you to consider ways of improving the organisation's success rate with the news media and thus its corporate reputation. The exercise should also help you to consider what makes a good press release and how best to manage the exchanges between the organisation and the media.

Task

Obtain copies of news reports about your organisation. If you are unable to do this, you might be able to find copies of reports about another organisation. If possible, ask your press office or PR manager for copies of press releases which were not published. Many organisations put their press releases on their websites; if possible, obtain copies of the periodicals in which the press releases were ultimately published.

Now use the table provided to rate the press releases. Give each press release points out of 10 for each of the criteria.

Story |

Newsworthiness |

Fit with editorial style (if you were able to obtain copies of the periodicals) |

Avoidance of an advertising style of phraseology |

|

|

|

|

Story |

Newsworthiness |

Fit with editorial style (if you were able to obtain copies of the periodicals) |

Avoidance of an advertising style of phraseology |

|

|

|

|

Feedback

You will probably have found that the press releases scored high on newsworthiness and on fit with the style of the journal. If this were not the case, the story would probably not have been accepted in the first place.

You may have found that the story also avoids advertising-type phraseology. This usually means that there are few adjectives in the story and that the products, brands and even the organisation are not mentioned until well into the story – typically the third or fourth paragraph.

If you were able to obtain copies of unsuccessful (unpublished) press releases, you will almost certainly have found that the stories scored lower on these factors. In some cases, the stories might not have been published because they were knocked off the front page by a major world event, however.

Ethics and Corporate responsibility

Public accountability has steadily increased throughout the 20th century and during the early 21st century. Organisations are now expected to conduct their affairs in the full glare of publicity and are held to be accountable for their actions. The public's power to compel organisations to act in ethical ways is exercised almost daily through the use of websites, newspaper reports, boycotts and even litigation.

Ethical theory

Ethics are the principles that define right and wrong. Ethical theory divides into the teleological theories, which state that acts should be defined as right or wrong according to the outcome of the acts, and the deontological approach, which states that acts can be defined as right or wrong regardless of the outcome. Teleology appears to imply that the end justifies the means and that a crime which does not succeed is no crime. Deontology implies that acts themselves can be defined as right or wrong, regardless of who performs the act. This means that something that is wrong for an individual is wrong for a government or a corporation. The deontological approach is illustrated by Kant's Categorical Imperative which states that each act must be based on reasons that anyone could act on, and that decisions to act must be based on reasons that the decision maker would accept for others to use in justifying their actions. In simple terms, this means that what is sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander.

In practice, of course, both approaches are fraught with difficulties. According to Kant, an 18th-century philosopher, if it is immoral for an individual to perform an act, it is also immoral for a government to perform it; yet many acts which are legal for governments are illegal for private citizens – going to war being an obvious example. In the corporate world, it is perfectly legal for an individual to run up debts with little or no prospect of being able to repay them, but such behaviour on the part of an organisation carries the death sentence for the organisation. Teleology is equally complex – to say that the end justifies the means opens the door to all sorts of skulduggery in the name of preserving jobs, shareholders’ investments or even directors’ perquisites.

The basis of corporate ethics is often the prevailing ethics of society at large. Corporations are sometimes established according to the religious or ethical stance of the founders (for example, Rowntree was founded as a model company run on Quaker principles) but often the moral code is expedient, based on prevailing attitudes. For example, most mission statements nowadays seem to contain a statement about environmentalism and virtually all contain a commitment to staff development, but these statements are frequently empty. Business is not inherently immoral, of course. The visionaries who founded some of the UK's most successful organisations did so by using a combination of firm ethical principles and solid business sense.

The ethical stance of an organisation is likely to attract people who have similar ethical principles, but research shows that most people have separate sets of morals for business and private life. Obviously the closer the organisation's ethical position is to that of its employees, the less likelihood there is of dissonance, therefore managers would be well advised to draw up a code of conduct to which employees feel they can subscribe. Organisations need to have a code of practice, and to monitor the code in practice, so that all stakeholders (and indeed outsiders) know what the organisation intends to do about its ethical responsibilities.

Establishing a corporate ethical framework

The starting point for any corporate ethical framework is likely to be the mission statement. Over the past 20 years or so it has become fashionable for organisations to have a mission statement in which it lays down clearly where it thinks the organisation is going and what kind of organisation it is intended to be. This is largely for strategic purposes, to ensure that everyone within the organisation is heading in the same direction and has a blueprint against which they are able to judge their actions.

Unfortunately, many mission statements are simply hollow rhetoric, intended to cover senior management's true intentions. Because there is a strong view that every organisation should have one, mission statements are drawn up without sufficient thought as to how they might be implemented, with the result that the ringing phrases and high moral tone of the statement are never actually put into practice. Table 5.3 shows the elements of a good mission statement.

At this moment, America's highest economic need is higher ethical standards – standards enforced by strict rules and upheld by responsible business leaders

George Bush,

US President, 2002

Element |

Description |

Purpose |

Why the organisation exists. Organisations do not necessarily exist purely to make a profit. For most founders of organisations, and indeed for most boards of directors, organisations exist to achieve something which senior management feels is really worth doing. Profit is what enables such organisations to stay in the game |

Strategy |

The organisation's competitive position and distinctive competence. This is the statement of how the organisation expects to distinguish itself from organisations offering similar benefits to customers |

Behaviour standards |

Norms and rules – ‘the way we do things round here’. Behaviour standards will include the way customers are dealt with and the way staff are treated |

Values |

These are the moral principles and beliefs that underpin the behaviour standards. Normally these values will first have been put in place by the founders or by the directors, but sometimes they will have grown up empirically over the life of the organisation |

Table 5.3 Elements of the mission

Pressure groups

Pressure groups such as environmentalists or local associations are clearly a factor in controlling corporate excesses. Sometimes organisations will try to use advertising to counter adverse publicity from pressure groups, but the success rate is limited.

McDonald's and the rainforests

McDonald's was attacked by environmental groups for indirectly encouraging the destruction of rainforests for the purpose of producing cheap beef. McDonald's responded with a series of full-page press adverts proving that beef for its hamburgers comes only from sources within the countries where they are eaten and is not imported from the Third World.

These advertisements had limited success because they actually attracted attention to the environmentalists’ claims, which up until then had been fairly low-profile due to lack of resources. Environmentalists continued to lobby and issue statements, some of which were actually untrue. McDonald's fought a successful libel action against one group, but again this backfired because it was seen as an example of a large corporation going after the little guy. Again, the case was widely publicised, which gave greater circulation to those anti-McDonald's statements which were true.

Of course, despite the fact that McDonald's is regularly attacked by pressure groups, the company still remains the world's largest and most popular restaurant group – so perhaps bad publicity is not as harmful as might be supposed.

Most journalists will make an honest effort to get both sides of the story, so when approached by a pressure group they will try to contact the organisation concerned. This is partly for legal reasons, to avoid libel accusations if the story is untrue, but also most journalists are professionals and prefer to write accurate and fair stories. This means that an organisation's press office, a PR manager or even a senior executive may be asked for comment with little or no prior warning, which can prove stressful to say the least.

Managers who find themselves in this position should try to avoid appearing evasive. It is better to use an expression such as, ‘I'm sorry, I'll have to look into that and get back to you,’ rather than to say, ‘No comment’. The former at least gives the impression that you are trying to help, whereas ‘No comment’ gives the impression that you are trying to hide something.

The ‘No comment’ approach is an example of defensive PR, which is an approach whereby managers respond to attacks from outside the organisation and counteract them as they arise. The safest way to handle this type of attack is to begin by trying to understand the enemy, and to this end the following questions should be asked:

1 Are they justified in their criticism?

2 What facts do they have at their disposal?

3 Who are they trying to influence?

4 How are they trying to do it?

Pressure groups are often justified in their criticisms and can bring evidence to bear to prove their claims. As with a complaint from a dissatisfied customer, the pressure group may be giving the organisation a last chance to correct the problem before taking matters further. In these circumstances it might be necessary to encourage the organisation to make any necessary changes rather than risk a PR disaster.

Most authors consider a proactive approach to pressure groups to be a safer course of action because it leads to fewer surprise calls from journalists. In the proactive case, managers need to decide the following:

1 Who to influence.

2 What to influence them about.

3 How to influence them.

4 How to marshal the arguments carefully to maximise the impact.

Consulting the possible pressure groups before implementing a proposed course of action is almost certainly going to be cheaper and easier than waiting for problems to arise. Often the relevant groups can be helpful in deciding on a course of action that will be seen as ethical, and will sometimes hold the organisation up as an example of good practice.

Professional ethics for public relations officers

The Arthur W. Page Society, a US organisation of public relations professionals, has the following principles enshrined in its constitution:

![]() Tell the truth. Let the public know what's happening and provide an accurate picture of the company's character, ideals and practices.

Tell the truth. Let the public know what's happening and provide an accurate picture of the company's character, ideals and practices.

![]() Prove it with action. Public perception of an organisation is determined ninety per cent by doing and ten per cent by talking.

Prove it with action. Public perception of an organisation is determined ninety per cent by doing and ten per cent by talking.

![]() Listen to the customer. To serve the company well, understand what the public wants and needs. Keep top decision makers and other employees informed about public reaction to company products, policies and practices.

Listen to the customer. To serve the company well, understand what the public wants and needs. Keep top decision makers and other employees informed about public reaction to company products, policies and practices.

![]() Manage for tomorrow. Anticipate public reaction and eliminate practices that create difficulties. Generate goodwill.

Manage for tomorrow. Anticipate public reaction and eliminate practices that create difficulties. Generate goodwill.

![]() Conduct public relations as if the whole company depends on it. Corporate relations are a management function. No corporate strategy should be implemented without considering its impact on the public. The public relations professional is a policymaker capable of handling a wide range of corporate communications activities.

Conduct public relations as if the whole company depends on it. Corporate relations are a management function. No corporate strategy should be implemented without considering its impact on the public. The public relations professional is a policymaker capable of handling a wide range of corporate communications activities.

![]() Remain calm, patient and good-humoured. Lay the groundwork for public relations miracles with consistent, calm and reasoned attention to information and contacts. When a crisis arises, remember that cool heads communicate best.

Remain calm, patient and good-humoured. Lay the groundwork for public relations miracles with consistent, calm and reasoned attention to information and contacts. When a crisis arises, remember that cool heads communicate best.

Source: Arthur W. Page Society

Such codes of ethics enable professionals to ensure that their actions are ethical and give them a yardstick against which they can control their daily activities.

Ethical analysis

Objective

Use this activity to assess some of the ethical issues surrounding your organisation's activities. The purpose of this activity is to compare the ethical stance of the organisation with your own ethical stance. This should help you to consider ways of closing the gap between the corporate ethics and the ethics of the employees, and also to consider the nature of the contract between employees and the organisation. To what extent can employees be expected to adopt the ethical stance of the organisation, and vice versa?

Task

Use the table provided to make a list of the activities your organisation is involved in. Next to each activity, indicate whether the activity is ethical, neutral or unethical according to your own code of ethics.

Activity |

Ethical |

Neutral |

Unethical |

|

□ |

□ |

□ |

|

□ |

□ |

□ |

|

□ |

□ |

□ |

|

□ |

□ |

□ |

|

□ |

□ |

□ |

|

□ |

□ |

□ |

|

□ |

□ |

□ |

|

□ |

□ |

□ |

|

□ |

□ |

□ |

|

□ |

□ |

□ |

|

□ |

□ |

□ |

|

□ |

□ |

□ |

Can you explain your answers? Why do you feel that some of the corporate activities are immoral? Who is affected by these activities? Why did you accept (or even assist with) carrying out activities which you think are unethical?

Your assessment: |

|

Feedback

Most organisations do things which some of their employees might regard as unethical. This does not prevent them from becoming involved in the process, or even helping with it.

You may have reconciled this internal conflict by accepting that not everyone's view is the same, and what is unethical for some people is acceptable to others. You may have reconciled the conflict by changing your own ethical stance. You may have reconciled it by thinking that the end justifies the means. You may even have changed your view of the organisation.

Finally, though, you may decide that you cannot reconcile the problem, and you have no alternative but to look for a job elsewhere. This is a rare, but not unknown, solution to this type of ethical dissonance.

Protecting reputation and image:

risk management

Life is risky. Business life is also risky, and managers need to be aware of this when organising their crisis management contingency plans.

No matter how carefully PR activities are planned and prepared for, crises will develop from time to time. Preparing for the unexpected is therefore a necessity. Some PR agencies specialise in crisis management, but a degree of advance preparation will certainly help if the worst should happen. Preparing for a crisis is similar to organising a fire drill: the fire may never happen, but it is as well to be prepared.

Crises may be very likely to happen, or extremely unlikely. For example, most manufacturing firms can expect to have a product-related problem sooner or later, and either need to recall products for safety reasons or need to make adaptations to future versions of the product. On the other hand, some crises are extremely unlikely. Assassination or kidnapping of senior executives is not common in most parts of the world, nor are products rendered illegal without considerable warning beforehand.

While no one can predict a crisis, appropriate foresight and thought can mean the difference between maintaining a stellar corporate reputation and the dreadful alternative.

Abbe Ruttenberg Sephos,

ABR Communications

Crises can also be defined as either within the organisation's control or outside the organisation's control. Many organisations have been beset by problems which were really not of their making. A classic example is that of Pan American Airlines (Pan Am) which, as the US flag-carrying airline, was regularly attacked by terrorist groups, culminating in the Lockerbie disaster in which a Pan Am 747 was destroyed over a Scottish village in 1988. In the aftermath of this disaster, Pan Am found itself unable to sell seats, and eventually the company went bankrupt.

In fact, Pan Am had systems in place for coping with terrorist bomb threats. The problem was that the company received an average of four such threats every day, virtually all of which proved to be hoaxes. If the airline had grounded its aircraft every time a threat was received, no Pan Am plane would ever have flown.

Pan Am further compounded the problem by failing to handle the crisis well from a PR perspective – the company was seen to be uncaring and somewhat heartless in its dealings with victims’ families and did not at first admit to having had a terrorist warning that a bomb was on board the plane.

Very few problems are entirely outside the organisation's control. In most cases, events can at least be influenced, if not controlled.

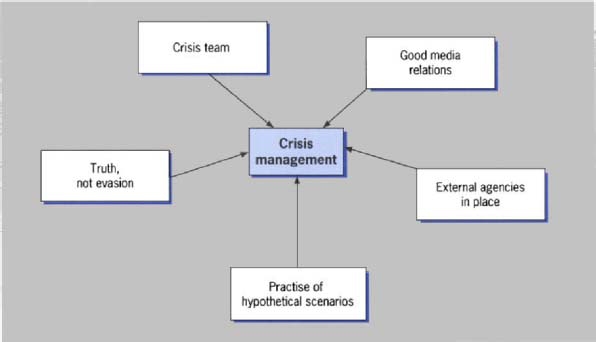

Sometimes, however, the cost of such influence is out of all proportion to the level of risk involved. Figure 5.2 shows the elements involved in good crisis management.

Figure 5.2 Elements of good crisis management

Establishing a crisis team

Ideally, the organisation should establish a permanent crisis management team of perhaps four or five individuals who are able to take decisions and act as spokespeople in the event of a crisis. Typical members might be the personnel manager, the safety officer, the factory manager, the PR officer and at least one member of the board of directors. Keeping the crisis team small means that communication between members is easy and fast.

The team should meet regularly to review potential risks and formulate strategies for dealing with crises. It may even be possible to rehearse responses in the case of the most likely crises. Importantly, the team should be trained in presentation techniques for dealing with the media, especially in the event of a TV interview.

The team should be able to contact each other immediately in the event of a crisis and should also be provided with deputies in case any members are away on business, on holiday, off sick or otherwise unavailable when a crisis occurs. The essence of planning for crises is to have as many fallback positions as possible; the need to have a Plan B is obvious, but it is wise to have a Plan C or even Plan D as well.

Dealing with the media in a crisis

One of the main PR problems inherent in crisis management is the fact that many crises are newsworthy. This means that reporters will be attracted to the organisation and its officers in the hope of getting comments or newsworthy statements which will help to sell newspapers.

Provided the groundwork has been laid, the organisation should already have a good relationship with the news media. This will help in the event of a crisis. However, many managers still feel a degree of trepidation when facing the press at a crisis news conference. The journalists are not there to help the organisation out of a crisis; they are there to hunt down (or create) a story. Their objectives are probably not compatible with those of the organisation, but they are under an obligation to report the news reasonably accurately.

Preparation is important. As soon as the crisis breaks, the crisis team should be ready to organise a press conference, preferably on the organisation's territory. The press conference should be held as soon as is reasonably possible, but the team should allow the spokespeople sufficient time to prepare themselves for the journalists and give a reasonable excuse for not talking to reporters ahead of time. The crisis team members should remember that they are in charge. It is their information, their crisis and their story. They are not under an obligation to the news media, but they are under an obligation to the organisation's shareholders, customers, employees and other publics. The media may or may not be helpful in communicating with these publics in a crisis situation.

Another important consideration is to ensure that the situation is not made worse by careless statements. Insurance and legal liability may be affected by anything that is said, so all statements should be checked beforehand.

Eurolines

In the summer of 1999, a Eurolines bus en route from Warsaw to London was involved in an accident with a lorry while driving through Germany. Many passengers were injured, some seriously, and the bus company was faced with a potential PR crisis even though the accident was not the fault of the Eurolines driver.

The injured passengers were taken straight to a hospital in Germany to be treated and Eurolines’ German agents compiled a list of passengers which also identified the injured. Those passengers who were fit enough were offered free telephone facilities so that they could notify their friends and families of the incident and reassure them of their safety. The passenger list was immediately sent to the Eurolines’ office at Victoria Coach Station in London so that waiting friends and relatives could have up-to-date information regarding the passengers. Eurolines’ London staff took telephone numbers of those waiting so that they could be notified of any changes in circumstances, and a hotline was set up for worried relatives to call for information.

Some of the passengers were too severely injured to be moved, but the majority were able to travel. They were offered the choice of returning to Warsaw or of continuing on to London on a second bus sent to Germany specifically for the purpose. Family and friends waiting in London were notified which of the options each passenger had taken. Since the second bus would be arriving in the small hours of the morning, the passengers would be accommodated at a five-star hotel near the bus station. Those waiting to meet the passengers were offered three options: to stay at the hotel, to go home and be called the next day or to have their friends ‘delivered’ by Eurolines or National Express coaches the following day, at Eurolines’ expense.

At the hotel, Eurolines’ emergency team was set up. The team consisted of senior Eurolines managers, a medical team, interpreters for Polish, Lithuanian, Russian and other language groups known to be on the bus, and a team of administrators briefed to arrange onward transportation and emergency help for people whose luggage was scattered along a German autobahn. As the passengers limped or were wheeled in they were offered sandwiches, tea and coffee and the opportunity for medical treatment and other assistance. Most of them continued straight to bed after a long and exhausting day. The location of the hotel was kept secret from the press. This was not particularly difficult to do since the accident was only really newsworthy in Germany, where it had happened.

The following morning, Eurolines staff were available both at the hotel and at the company's offices to offer any further assistance. Passengers and those meeting them were offered exemplary service, including free coach tickets to any UK location, access to embassy consular services and ongoing medical treatment for those needing it. Eventually, once the accident enquiry was completed in Germany, the passengers also received substantial compensation. All those involved, whether as passengers or as friends and relatives of passengers, were delighted with the way Eurolines handled the crisis. What was potentially a PR disaster was turned into a PR victory by the professional way the crisis was handled – despite the fact that Eurolines rarely have the opportunity to put these skills into practice.

Crisis teams need to have a special set of talents, as well as the training needed to perform their ordinary jobs. Rapid communication and rapid response are essential when the crisis occurs. Good relationships with the news media will pay off in times of crisis.

Crisis management should not be left until the crisis happens. Everyone involved should be briefed beforehand on what the crisis policy is. This enables everyone to respond appropriately, without committing the organisation to inappropriate actions – in simple terms, being prepared for a crisis will help to prevent panic reactions and over-hasty responses which might come back to haunt the organisation later.

Establishing a crisis team

Objective

Use this activity to consider how to establish a crisis team in your organisation. The purpose of this exercise is to help you consider the types of crisis which might affect your organisation, and thus the particular individuals who would be most effective in dealing with the crisis. These individuals are not necessarily the most senior in the organisation. This exercise should also focus your thinking on the possible training and support these people would need in advance of a crisis.

Task

1 Use the table provided to list the possible types of crisis which might befall your organisation. Be imaginative – the point about a crisis is that it is unusual!

2 Then, in the second table, list the departments that might need to become involved in handling that type of crisis.

Within each department, you should be able to identify appropriate individuals who would possess the necessary expertise and knowledge to be able to handle the crisis. Such individuals should have the following characteristics:

![]() They should be team workers

They should be team workers

![]() They should have been with the organisation long enough to understand the corporate vision and objectives

They should have been with the organisation long enough to understand the corporate vision and objectives

![]() They should have a good network of contacts within the organisation

They should have a good network of contacts within the organisation

![]() They should have Sufficient formal authority, or sufficient respect within their departments, to be able to push decisions through.

They should have Sufficient formal authority, or sufficient respect within their departments, to be able to push decisions through.

List these individuals in the right-hand column of the table.

|

Departments involved |

Individuals with necessary skills and knowledge |

Crisis 1 |

|

|

Crisis 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

Crisis 4 |

|

|

Crisis 5 |

|

|

|

|

|

Feedback

You will almost certainly have found that some departments and individuals feature frequently in the table you have drawn up. The ones who feature most frequently are the ones who should be formed into the crisis team.

There should also be a cut-off point, however. In some cases there will be people who only feature once in your list; although you may feel that it is desirable to include such people in your team, you need to decide whether it is likely that they will be needed for dealing with most of the possible crises. Obviously some crises are more likely to occur than others, so there is little point in including someone on the crisis team who would rarely be called upon to act.

Recap

Recap

Consider how public relations activities help in generating and managing reputation

![]() PR plays a strategic role in relationship marketing and is concerned with building the long-term reputation of the organisation with the organisation's publics. It extends beyond the tactical tools of publicity and press relations.

PR plays a strategic role in relationship marketing and is concerned with building the long-term reputation of the organisation with the organisation's publics. It extends beyond the tactical tools of publicity and press relations.

![]() The tools used by PR include press releases, sponsorship, publicity stunts, word-of-mouth, corporate advertising and lobbying.

The tools used by PR include press releases, sponsorship, publicity stunts, word-of-mouth, corporate advertising and lobbying.

Assess the effectiveness of your organisation's press releases

![]() Press releases are stories about the organisation, published in newspapers, posted on the Internet or broadcast on television and radio. Press releases are produced in order to communicate values about the organisation and to enhance its reputation.

Press releases are stories about the organisation, published in newspapers, posted on the Internet or broadcast on television and radio. Press releases are produced in order to communicate values about the organisation and to enhance its reputation.

![]() There are three criteria for a successful press release: the story must be newsworthy, it should not be a thinly veiled advertisement and it must fit with the editorial style of the paper or magazine to which you are sending it.

There are three criteria for a successful press release: the story must be newsworthy, it should not be a thinly veiled advertisement and it must fit with the editorial style of the paper or magazine to which you are sending it.

Understand the ethical problems that inform good corporate citizenship and explore ways to improve the ethical stance of the organisation

![]() In some cases the corporate ethical stance will conflict with the ethical stances of the organisation's employees. There is evidence that people are able to adopt one ethical stance in their personal lives and an entirely different stance in their professional lives.

In some cases the corporate ethical stance will conflict with the ethical stances of the organisation's employees. There is evidence that people are able to adopt one ethical stance in their personal lives and an entirely different stance in their professional lives.

![]() An organisation needs to have an ethical framework that explains to its stakeholders what it intends to do about its ethical responsibilities. This might be captured in a mission statement or presented as a separate code of practice.

An organisation needs to have an ethical framework that explains to its stakeholders what it intends to do about its ethical responsibilities. This might be captured in a mission statement or presented as a separate code of practice.

Identify how you can protect your organisation's image and reputation in the event of a corporate crisis

![]() Organisations should regularly assess potential risks to their reputation and image and have contingency plans in place for dealing with crises.

Organisations should regularly assess potential risks to their reputation and image and have contingency plans in place for dealing with crises.

![]() Having good media relations, established relationships with external agencies, practising hypothetical scenarios, being truthful and having a crisis team in place are all elements of good crisis management.

Having good media relations, established relationships with external agencies, practising hypothetical scenarios, being truthful and having a crisis team in place are all elements of good crisis management.

![]() A crisis team is a group of people within the organisation whose purpose is to provide a coherent corporate response to a potential public relations crisis.

A crisis team is a group of people within the organisation whose purpose is to provide a coherent corporate response to a potential public relations crisis.

More @

More @

Branson, R. (Foreword), Barry, A. (2002) PR Power: Inside Secrets from the World of Spin, Virgin Business Guides

Find out why some of the world's most successful entrepreneurs, such as Jeff Bezos, Anita Roddick and Stelios Haji-Ioannou, view PR with a passion.

Larkin, J. (2002) Strategic Reputation Risk Management, Palgrave-MacMillan

This book provides practical models and checklists designed to plan reputation management and risk communication strategies.

Neef, D. (2003) Managing Corporate Reputation and Risk: Developing a Strategic Approach to Corporate Integrity Using Knowledge Management, Butterworth-Heinemann

The American Marketing Association provides articles and webcasts to improve your public relations – www.marketingpower.com/topics13.php

www.knowthis.com is another online marketing portal – the Marketing Virtual Library. Use ‘public relations’ to search.