11

Continuous Learning Culture

“Real learning gets to the heart of what it means to be human. Through learning, we recreate ourselves. Through learning, we become able to do something we never were able to do. Through learning, we re-perceive the world and our relationship to it. Through learning, we extend our capacity to create, to be part of the generative process of life. There is within each of us a deep hunger for this type of learning.”

—Peter M. Senge, The Fifth Discipline

The continuous learning culture competency describes a set of values and practices that encourage individuals—and the entire enterprise—to continually increase knowledge, competence, performance, and innovation. This is achieved by becoming a learning organization, committing to relentless improvement, and promoting a culture of innovation.

Why a Continuous Learning Culture?

The pace of technology innovation in the 21st century is unprecedented. Organizations today are facing complex, turbulent forces that are creating both uncertainty and opportunity. Startup companies commonly challenge the status quo by transforming, disrupting, and even taking over entire markets. Tech giants are entering entirely new markets such as banking and healthcare. Expectations from a new generation of workers, customers, and society as a whole challenge companies to think and act beyond balance sheets and quarterly earnings reports. Due to all of these factors and more, one thing is certain: organizations in the digital age need to adapt rapidly or face decline— and potentially extinction.

What’s the solution? Organizations have to evolve their way of thinking and working so they can constantly learn and adapt faster than the competition. Put simply, enterprises must have a continuous learning culture that applies the collective knowledge, experience, and creativity of their workforce, as well as customers, supply chain, and the broader ecosystem. Learning organizations manage the powerful forces of change to their advantage and are characterized by curiosity, invention, entrepreneurship, and informed risk-taking. Such organizations replace commitment to the status quo with a mindset of relentless improvement, while providing stability and predictability. Moreover, decentralized decision-making (Principle #9) becomes the new way of working, as leaders turn their focus to developing the vision and strategy, and to helping people achieve their full potential.

Any organization can begin the journey to a continuous learning culture by focusing its transformation along the three dimensions listed below and shown in Figure 11-1.

Figure 11-1. The three dimensions of a continuous learning culture

Learning organization. Employees at every level are learning and growing so that the organization can transform and adapt to an ever-changing world.

Innovation culture. Employees are encouraged and empowered to explore and implement creative ideas that enable future value delivery.

Relentless improvement. Every part of the enterprise focuses on continuously improving its solutions, products, and processes.

Each dimension is described next.

Learning Organization

Developing a learning organization is the first dimension of a continuous learning culture. Learning organizations invest in and facilitate ongoing employee growth. When everyone in the organization is continuously learning, it fuels the enterprise’s ability to dynamically transform itself as needed to anticipate and take advantage of opportunities that create a competitive edge. Learning organizations excel at creating, acquiring, and transferring knowledge while modifying practices to integrate the new insights.1, 2

1. David A. Garvin, “Building a Learning Organization.” Harvard Business Review, July-August 1993, https://hbr.org/1993/07/building-a-learning-organization.

2. Peter Senge. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization, Kindle edition (Penguin Random House, 2010).

These organizations understand and nurture the intrinsic motivation of people to learn and gain mastery for the benefit of the enterprise.3

3. Daniel H. Pink, Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, Kindle edition (Penguin Group, 2009).

Learning organizations are distinguished from those focused on simply improving efficiency using the earlier management methods promoted by Frederick Taylor. In Taylor’s model, learning is focused on management, everyone else is expected to follow the policies and practices that management creates. Becoming a learning organization breaks this model and challenges the status-quo thinking that has led many former market leaders to bankruptcy. Learning drives innovation, leads to greater sharing of information, enhances problem-solving, increases the sense of community, and surfaces opportunities for more efficiency.4

4. Michael Marquardt, Building the Learning Organization, Kindle edition (Nicholas Brealey Publishing, 2011).

As described by Peter Senge in The Fifth Discipline, transforming into a learning organization requires the following distinct disciplines.

Personal mastery. Employees develop as ‘T-shaped’ people. They build a breadth of knowledge in multiple disciplines for efficient collaboration and deep expertise aligned with their interests and skills. T-shaped employees are a critical foundation of Agile teams and ARTs.

Shared vision. Forward-looking leaders envision, align with, and open up exciting possibilities. They invite others to share and contribute to a common view of the future. Such leaders offer a compelling vision that inspires and motivates people to bring it about.

Team learning. Teams work collectively to achieve common objectives by sharing knowledge, suspending assumptions, and learning together. Agile teams are cross-functional and apply their diverse skills to group problem-solving and learning. This practice is routine in high-performing teams.

Mental models. Teams make their existing assumptions and hypotheses visible while working with an open mind to create new models of thinking based on the Lean-Agile mindset and deep customer knowledge. Mental models take complex concepts and make them easy to understand and apply.

Systems thinking. The organization sees the larger picture, and applies a systems thinking approach (Principle #2) to learning, problem-solving, and solution development. In the Scaled Agile Framework (SAFe), this approach extends to the business through Lean Portfolio Management (LPM), which ensures that the enterprise is investing in experimentation and learning to drive better business outcomes.

In addition to the above, SAFe promotes a learning organization in the following ways:

Lean-Agile leaders promote, support, and continually exhibit personal mastery of the new way of working.

A shared vision is iteratively refined during each Program Increment (PI) planning event. This influences Business Owners, the teams on each Agile Release Train (ART), and the entire organization.

Teams learn continuously through daily collaboration and problem-solving, supported by events such as team retrospectives and the Inspect and Adapt (I&A) event.

Design thinking and the team and technical agility competency provide a set of powerful practices and tools that promote continuous learning as part of the team’s regular work.

Leaders exhibit and teach systems thinking, actively engage in solving problems, and eliminate impediments and ineffective internal systems. They collaborate with the teams to reflect at key milestones and help them identify and address shortcomings.

Many SAFe principles support a learning culture (e.g., Principle #4, Base milestones on objective evaluation of working systems; Principle #5, Building incrementally with fast integrated learning cycles; Principle #8, Unlock the intrinsic motivation of knowledge workers, Principle #9; Decentralized decision-making; and more).

Innovation Culture

Developing an innovation culture is the second dimension of a continuous learning culture. As described in Chapter 3, Lean-Agile Mindset, innovation is one of the four pillars of the SAFe House of Lean. But the kind of innovation needed to compete in the digital age cannot be infrequent or random. It requires an innovation culture, which exists when leaders create a work environment that supports creative thinking, curiosity, and challenging the status quo. When an organization has an innovation culture, employees are encouraged and enabled to do the following:

Explore ideas for enhancements to existing products

Experiment with ideas for new products

Pursue fixes to chronic defects

Create improvements to processes that reduce waste

Remove waste and improve productivity

Some organizations support innovation by allowing people to explore and experiment through intrapreneurship programs, innovation labs, hackathons, and other means. SAFe takes this a step further by providing a regular, consistent time during each PI for all members of the ART to pursue innovation activities during the IP iteration. Innovation is a key element of Agile product delivery and the continuous delivery pipeline. In Chapter 7, Agile Product Delivery, we illustrated that teams do continuous exploration during each iteration as well.

The following sections provide practical guidance for initiating and continuously improving an innovation culture.

Innovative People

The foundation of an innovation culture is the recognition that systems and cultures don’t innovate; people do. Fostering innovation as an enterprise capability requires a commitment to encourage creativity, experimentation, and risk-taking. Acquiring this capability may necessitate coaching, mentoring, and formal training in the skills and behaviors of entrepreneurs and innovation. Individual goals and learning plans should enable and empower people to innovate. Rewards and recognition that balance intrinsic and extrinsic motivation reinforce the importance of everyone being an innovator. Criteria for hiring new employees should include evaluating whether candidates are a good fit within an innovation culture. Opportunities and paths for advancement should be clear and available for people who demonstrate exceptional talent and performance as innovation agents and champions.5

5. Cris Beswick, Derek Bishop, and Jo Geraghty, Building a Culture of Innovation, Kindle edition (Kogan Page, 2015).

Time and Space for Innovation

Building time and space for innovation includes offering work areas that promote creative activities (see Chapter 10, Organizational Agility), as well as setting aside dedicated time from routine work to explore and experiment. Innovation space can also include the following:

Frequent interactions with customers, the supply chain, and local communities connected to the organization

Temporary and limited suspension of norms, policies, and systems (within legal, ethical, and safety boundaries) to challenge existing assumptions and explore what’s possible

Cadenced-based (IP iteration, hackathons, dojos, etc.) and ad hoc innovation activities

Communities of Practice (CoPs) that collaborate regularly to share information, improve their skills, and actively work on advancing the general knowledge of a domain

Go See (Gemba)

Often, the best innovation ideas are sparked by seeing the problems to be solved first-hand—witnessing how customers interact with products or the challenges they face using existing processes and systems. Gemba is a Japanese term and Lean practice, meaning ‘the real place,’ the place where the customer’s work is actually performed.

SAFe explicitly supports gemba through continuous exploration. Making firsthand observations and hypotheses visibly shifts the creative energy of the entire organization toward developing innovative solutions. Leaders should also openly share their views on the opportunities and challenges the organization faces to focus innovation efforts on the things that matter the most.

Experimentation and Feedback

Organizations with an innovation culture frequently conduct experiments to progress iteratively toward a goal. This scientific approach is the most effective way to generate insights that lead to breakthrough results. Regarding his many unsuccessful experiments to create an incandescent light bulb, Thomas Edison famously said, “I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.” The thinking behind the scientific method is that experiments don’t fail; they simply produce the learning needed to accept or reject a hypothesis. Cultures that promote a fear of failure significantly inhibit innovation.

In contrast, innovation cultures depend on learning from experiments and incorporate those findings into future exploration. When leaders create the psychological safety described in Chapter 5, Lean-Agile Leadership, people are encouraged to experiment. They feel empowered to solve big problems, to seize opportunities, and to do so without fear of blame, even when the results of the experiments suggest going in a different direction.

Pivot Without Mercy or Guilt

Every innovation begins as a hypothesis: a set of assumptions and beliefs regarding how a new or improved product will delight customers and help the organization achieve its business objectives. However, until they’re validated by feedback from customers, hypotheses are just informed guesses. As we described in Chapter 9, Lean Portfolio Mangaement, the fastest way to accept or reject a product development hypothesis is to experiment by building a Minimum Viable Product (MVP).6 An MVP is a version of a new product that allows a team to collect, with the least effort, the maximum amount of validated learning from customers.

6. Eric Ries, The Startup Way, Kindle edition (Currency, 2017).

Target users test MVPs and provide fast feedback. In many cases, the feedback is positive and warrants further investment to bring the innovation to market or into production. In other instances, the results may cause a change in direction. This could be as simple as a set of modifications to the product followed by additional experiments for feedback, or it could prompt a pivot to a different product or strategy. When the fact-based evidence indicates that a pivot is required, the shift in direction should occur as quickly as possible, without blame or consideration of sunk costs in the initial experiments.

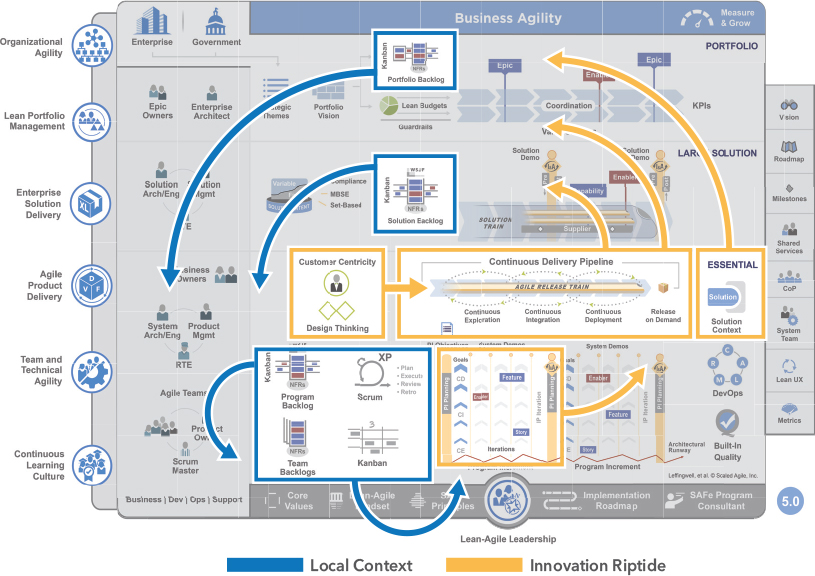

Innovation Riptides

To create an innovation culture, organizations have to go beyond catchy slogans, innovation teams, and popular techniques such as hackathons and coding dojos. A fundamental rewiring of the enterprise’s DNA is needed to fully leverage the innovation mindset and create the processes and systems that promote innovation. As shown in Figure 11-2, SAFe provides the bidirectional flow needed to foster innovation throughout a portfolio.

Local Context Innovation Riptide

Figure 11-2. SAFe includes critical elements to support a consistent, continuous flow of innovation

The continuous flow of innovation is built on the foundation of SAFe Principle #9, Decentralized decision-making. Some innovation starts as strategic initiatives that are realized through portfolio epics and Lean budgets for value streams. During the implementation of these epics, additional opportunities for improving the solution are often identified by teams, suppliers, customers, and business leaders.

Other potential innovations come from many different directions (teams, ARTs, and portfolio) and flow into each other, creating an ‘innovation riptide’ that results in a tidal wave of new ideas flowing into the various backlogs that support innovation and solution development.

Some innovations flow directly into the program Kanban as features, while larger innovations may result in the creation of an epic that flows into the portfolio Kanban. It’s this repeating cycle of innovation occurring at all levels that creates the innovation riptide, illustrated by the swirling arrows on the Big Picture in Figure 11-2. Moreover, SAFe provides the structure, principles, and practices to ensure alignment so that all teams progress toward the larger aim of the portfolio.

Relentless Improvement

Relentless improvement is the third dimension of a continuous learning culture and is also the fourth pillar in the SAFe House of Lean (Chapter 3).

Kaizen, the relentless pursuit of perfection, is a core belief of Lean. Although perfection is unattainable, the act of striving for perfection leads to relentless improvements to products and services. In the process, companies create more and better products for less money, with happier customers, all leading to higher revenues and greater profitability. Taiichi Ohno, the creator of what became Lean, emphasized that the only way to achieve relentless improvement is for everyone at all times to have a kaizen mindset. The entire enterprise—which is also a system, made up of executives, product development, accounting, finance, and sales—is continuously challenged to improve.7

7. Jeffery K. Liker, Developing Lean Leaders at All Levels, Kindle edition (Lean Leadership Institute Publications, 2011).

But improvement requires learning. And the root causes and solutions to the problems that organizations face are rarely so easily identified. The Lean model for continuous improvement is based on a series of small iterative and incremental improvements, problem-solving tools, and experiments that enable the organization to learn its way to the most promising answers.

The sections that follow further describe how relentless improvement is a critical component of a continuous learning culture.

Constant Sense of Danger

SAFe uses the term relentless improvement in its House of Lean to convey that improvement activities are essential to the very survival of an organization and should be given priority, visibility, and attention. This closely aligns with another core belief of Lean: focus intensely on delivering value to customers by providing products and services that solve their problems in ways they will prefer over your competitors’ solutions.

SAFe promotes both ongoing and planned improvement efforts through its core values, practices, and events. Continuous improvement is built into the way Agile teams and trains do their work; it’s not added later.

Optimize the Whole

Optimizing the whole is another view of systems thinking, one that increases the effectiveness of the entire solution by producing a sustainable flow of value versus optimizing individual teams, silos, or subsystems. So, improvements made to one area, team, or domain should not be done if they will negatively affect the overall system.

Organizing around value in ARTs, Solution Trains, and value streams creates opportunities for people in all domains to have regular discussions and debates about how to enhance overall quality, the flow of value, and customer satisfaction.

Problem-Solving Culture

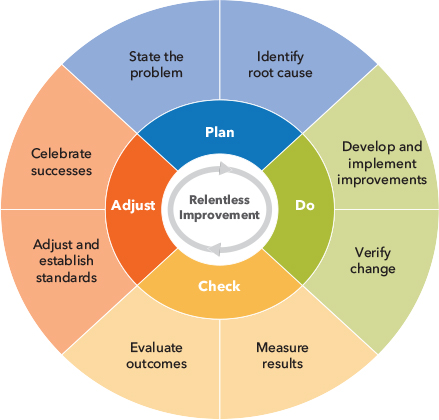

In Lean, root-cause analysis and problem-solving drive continuous improvement. Lean recognizes that a gap always exists between the current state and the desired state, requiring an iterative and scalable problem-solving process. The Plan–Do–Check–Adjust (PDCA) cycle provides that iterative and scalable process. Until the target state is achieved, the process is repeated. This PDCA improvement cycle can be applied to anything, from individual teams trying to optimize software response time, to enterprises attempting to overcome a steady decline in market share.

A problem-solving culture treats difficult issues as opportunities for improvement in a blameless environment, where employees at all levels are empowered and equipped with the time and resources to identify and overcome obstacles.

SAFe provides the processes and tools that teams, ARTs, and Solution Trains need to facilitate the PDCA cycle shown in Figure 11-3.

Figure 11-3. The PDCA problem-solving cycle scales from individual teams to entire organizations

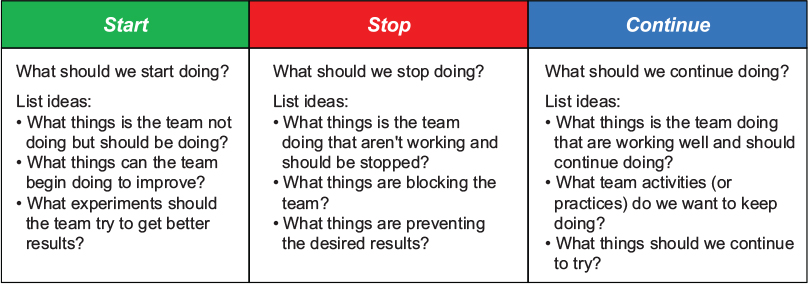

As part of this, teams conduct retrospectives at the end of every iteration following one of the many techniques available such as the ‘start-stop-continue’ method, which is a simple and effective way for teams to reflect and determine the following (see Figure 11-4):

What is the team not doing but should start doing?

What is the team doing that’s not working and should be stopped?

What is the team doing that’s working well and should continue doing?

Figure 11-4. Start-stop-continue retrospective method

ARTs and Solution Trains also conduct problem-solving workshops as part of the I&A event at the end of each PI (see Chapter 7). This workshop uses thinking tools such as ‘fishbone’ diagrams (and five whys) for root-cause identification, and Pareto analysis to identify the most likely causes of the problem being addressed (see Figure 11-5).

Figure 11-5. Fishbone (Ishikawa) diagram and Pareto analysis

Reflect at Key Milestones

It’s easy to defer improvement activities in favor of more ‘urgent work’—developing new features, fixing defects, responding to the latest outage. And yet it’s often the case that this more urgent work is less important than the improvement activities, which would lead to faster value delivery, higher quality, and more delighted customers over time. As Stephen R. Covey would say, “We must never become too busy sawing to take time to sharpen the saw.”8 To avoid neglecting this critical activity, relentless improvement is part of the workflow for Agile teams and trains, which is done on a regular cadence.

8. Stephen R. Covey, The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Restoring the Character Ethic, revised edition (New York: Free Press, 2004).

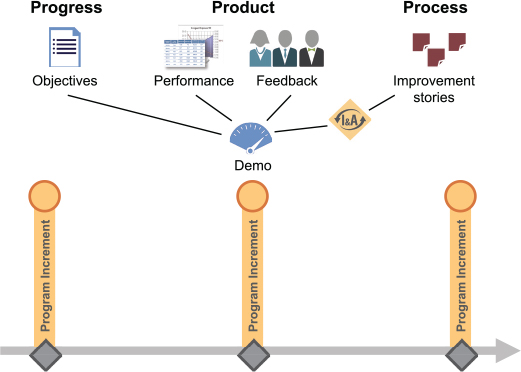

For individual teams, SAFe recommends retrospectives at iteration boundaries (at a minimum) and at the moment problems arise, when needed. ARTs and Solution Trains reflect every PI as part of the I&A event. In large product development efforts, this cadence-based milestone (event) provides predictability, consistency, and rigor to the process of relentless improvement (Figure 11-6).

Figure 11-6. PI milestones provide a time to measure and reflect

Fact-Based Improvement

Fact-based improvement leads to changes guided by the data surrounding the problem and informed solutions, not by opinions and speculation. Improvement results are objectively measured, focusing on empirical evidence. This helps an organization concentrate more on the work needed to solve problems and less on assigning blame.

Summary

Too often organizations fall into the trap of assuming that the culture, processes, and products that led to today’s success will also guarantee future results. That mindset increases the risk of decline and failure. The enterprises that will dominate their markets going forward will be adaptive learning organizations, with the ability to learn, innovate, and relentlessly improve more effectively and faster than their competition.

Competing in the digital age requires investment in both time and resources for innovation, built upon a culture of creative thinking and curiosity—an environment where norms can be challenged, and new products and processes emerge. Alongside this, relentless improvement acknowledges that the survival of an organization is never guaranteed. Everyone in the organization will be challenged to find and make incremental improvements, and priority and visibility is given to this work.

A continuous learning culture will likely be the most effective way for this next generation of workers to relentlessly improve, and the successful companies that employ them.