5

Giving Benefits

in Major Sales

We’ve seen in Chapter 4 how the SPIN Model provides a strong probing framework for the Investigating stage of the call. In this chapter, I want to show you what Huthwaite’s research found about the Demonstrating Capability stage (Figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1. The Demonstrating Capability stage: Offering your solutions and capabilities to the customer.

Features and Benefits: The Classic Ways to Demonstrate Capability

Sales training and books on selling have given a lot of attention to methods for Demonstrating Capability. Since the 1920s it’s been recognized that some ways of presenting solutions to customers are more persuasive than others. Anybody who has been through a sales-training program in the last 60 years is likely to have been taught the terms Features and Benefits as the two ways that you can describe your products or services. We’re all so familiar with the concept that it scarcely seems necessary to explain that Features are facts about a product and are unpersuasive, whereas Benefits—which show how Features can help the customer—are a much more powerful way to describe your capabilities. If there was one area of selling where we expected our research merely to confirm the conventional wisdom, it was here with Features and Benefits.

But we were in for some surprises. Benefits, in the way you’ve probably been taught to use them, are ineffective in larger sales and are likely to create a negative response from the customer. And even something as simple as defining a Benefit is much harder than it seems. Before looking at our conclusions, let’s begin by reviewing some basics.

Features

Everybody knows what Features are. They are facts, data, or information about your products or services. Typical examples of Features include “This system has 512K buffer storage,” “There is a four-stage exposure control,” and “Our consultants have a background in educational psychology.” Features, as every writer has observed since the 1920s, are unpersuasive. Because they give neutral facts, they don’t much help your sales presentation. On the other hand, the consensus of writers is that they don’t harm you either.

What does our research show? From an analysis of the number of Features used in 18,000 sales calls, we found the following (Figure 5.2):

Figure 5.2. Features.

![]() Overall, the level of Features is slightly higher in unsuccessful calls (which, you’ll remember, are those leading to Continuations and No-sales). But this difference is small enough for us to conclude that the conventional wisdom is right—Features are neutral. They don’t help the call, but they don’t harm it much either.

Overall, the level of Features is slightly higher in unsuccessful calls (which, you’ll remember, are those leading to Continuations and No-sales). But this difference is small enough for us to conclude that the conventional wisdom is right—Features are neutral. They don’t help the call, but they don’t harm it much either.

![]() In small sales there’s a slight positive relationship between the use of Features and call success, so the calls higher in Features are slightly more likely to result in Orders or Advances. This relationship isn’t true in larger sales.

In small sales there’s a slight positive relationship between the use of Features and call success, so the calls higher in Features are slightly more likely to result in Orders or Advances. This relationship isn’t true in larger sales.

![]() In larger sales, Features have a negative effect when used early in the call and a neutral effect when used later.

In larger sales, Features have a negative effect when used early in the call and a neutral effect when used later.

![]() Users respond more positively to Features than do decision makers.

Users respond more positively to Features than do decision makers.

![]() In the middle of very complex selling cycles of technical products, the customer sometimes develops a “Features appetite.” When this happens, the customer demands considerable product detail and may respond positively to Features. It’s at this stage of the selling cycle that technical experts, systems analysts, and other sales-support people often have a positive impact on a customer.

In the middle of very complex selling cycles of technical products, the customer sometimes develops a “Features appetite.” When this happens, the customer demands considerable product detail and may respond positively to Features. It’s at this stage of the selling cycle that technical experts, systems analysts, and other sales-support people often have a positive impact on a customer.

We also found some curious relationships between the use of Features and the type of response from customers, which we’ll explore more in the next chapter. But generally, our work on Features confirmed what writers have been saying for 50 years. Features are low-power statements that do little to help you sell. It’s better to use Benefits than Features.

What’s a Benefit?

Our problems started when we began to investigate Benefits. While everybody agrees on the definition of a Feature, no two writers on selling seem to have the same definition of a Benefit. Here are some of the many definitions that we uncovered from a miserable month spent reading every sales book and training program we could find:

A Benefit shows how a Feature can help a customer.

A Benefit must have a cost saving for the buyer. A Benefit is any statement that meets a need.

A Benefit has to appeal to the personal ego needs of the buyer, not to organizational or departmental needs.

A Benefit must be something which you can offer and which your competitors can’t.

A Benefit gives a buying motive.

There are more. Some definitions emphasize financial elements, and some concentrate on personal appeal. Others accept any elaboration of a Feature, such as explaining how it can be used. My personal favorite was from a sales manager in Honeywell who told me, “A Benefit is anything you say to a customer that’s smarter than a Feature.”

Which Definition Is Right? How can we tell which of these definitions is better than the others? There’s only one valid test: The best of these rival definitions is the one that has the most positive impact on customers. Is there one of these types of Benefits that occurs more often than others in successful calls? Our research team set out to test this by watching sales calls and counting how often the different types of Benefits were used in calls that succeeded and in calls that failed. After this initial testing of a half-dozen different definitions, we chose two for our major research test:

![]() Type A Benefit. This type shows how a product or service can be used or can help the customer.

Type A Benefit. This type shows how a product or service can be used or can help the customer.

![]() Type B Benefit. This type shows how a product or service meets an Explicit Need expressed by the customer.

Type B Benefit. This type shows how a product or service meets an Explicit Need expressed by the customer.

We chose the Type A definition because it was the most common one used in the better sales-training programs. Most readers of this book will have been taught to use the Type A Benefit. In contrast, the Type B Benefit was our own definition. We chose it after watching hundreds of very effective salespeople in larger sales and analyzing the types of product statements they made to their customers.

At first sight, these two definitions of a Benefit seem very similar. However, their effect on customers is dramatically different, so it’s worth examining how the two differ. For example, suppose I’m selling you a computer system and I say, “I assume you want a 32-bit system like our Suprox machine because, if you ever use graphics, it will be significantly faster for you.” Have I made a Type A or a Type B statement? It can’t be Type B, for I’ve assumed that you want faster graphics; you haven’t actually expressed a need for graphics, let alone faster ones.

Take another example. You tell me that your present machine has a reliability problem. I reply, “Because our Suprox machine uses a new generation of high-reliability components, it could solve your present reliability problem.” What kind of statement is this? This time you’ve certainly expressed a need. You’ve told me that your present machine is unreliable. But have you expressed an Explicit Need? No; telling me that your present machine has a reliability problem is an Implied Need (a problem, difficulty, or dissatisfaction). So my statement meets an Implied Need, not an Explicit Need. Once again, we should classify it as a Type A Benefit, not a Type B.

How Important Is the Difference? In our research test we found that the Type A Benefit is quite strongly related to success in smaller sales but is only slightly related to success in larger sales. (We’ll see why later in this chapter.) In contrast, the Type B Benefit is very strongly related to success in all sizes of sales.

I don’t know about you, but personally I find it hard to remember which is which whenever anything is labeled A or B. I wasn’t the only one who found it confusing to refer to Type A and Type B Benefits, so we soon decided that it would be better to avoid further difficulties by putting more descriptive names in place of A and B. We called the Type A Benefit an “Advantage.” And for the Type B Benefit, because it was so strongly related to success, we kept the name “Benefit.”

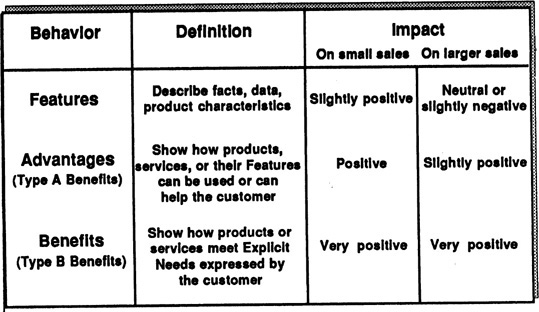

Thus, what emerged from our research are three kinds of statements (or behaviors) that you can use to demonstrate capability, as shown in Figure 5.3. It’s important to remember that if you’ve been through sales training in the last 20 years, you’ve probably been taught to use a lot of Type A Benefits—or Advantages. But as you can see in Figures 5.3 and 5.4, Advantages are more powerful in simpler sales than they are in the larger sales that are the subject of this book.

Figure 5.3. Features, Advantages, and Benefits.

Figure 5.4. Advantages (Type A Benefits).

Almost certainly, you’ll experience some confusion between the definition of Benefit that we’re using here and the definitions you’ve learned in the past. Most salespeople I’ve worked with hate quibbling about definitions, and I don’t blame them. But in this case, definitions are vitally important. For example, the Motorola Canada productivity study described in Appendix A shows that salespeople who used Benefits rather than Advantages increased their dollar volume of sales by 27 percent. That’s more than a quibble. When the definition is derived from choosing the statements that have the highest impact on customers, then we’re not just playing with words. Because the differences between Features, Advantages, and Benefits are so important, I’d like to give you a chance to test your understanding of them by working through the following short transcript. See if you can pick out which of the 10 product statements offer Features, Advantages, or Benefits. Then check your answers against the ones given at the end of this chapter.

Types of Product Statements

Now that you’re familiar with the rather special way we use the terms Advantages and Benefits, let’s examine the research evidence in more detail.

The Relative Impacts of Features, Advantages, and Benefits

I’ve said that Advantages—statements showing how your product can be used or can help the customer—have a much more positive impact on small sales than on larger ones. Why? It seems odd that the impact should be so much less in the large sale. The most probable answer goes back to the points I made about simple sales in Chapter 4. Remember that we showed how you could be very successful in smaller sales by using Situation and Problem Questions to uncover Implied Needs and then offering solutions.

What would these solutions be in terms of Features, Advantages, and Benefits? They can’t be Benefits because, as we’ve seen, you can only make a Benefit if you address an Explicit Need that the customer has expressed. In this case the solutions are offered to Implied Needs, so they must be either Features or Advantages. We’ve seen that offering solutions to Implied Needs isn’t effective in larger sales. So this use of Features and Advantages, which can work perfectly well in a small sale, is likely to be ineffective as the sale grows larger (Figure 5.5).

Figure 5.5. A recipe for success in the smaller sale, but for disaster in larger sales.

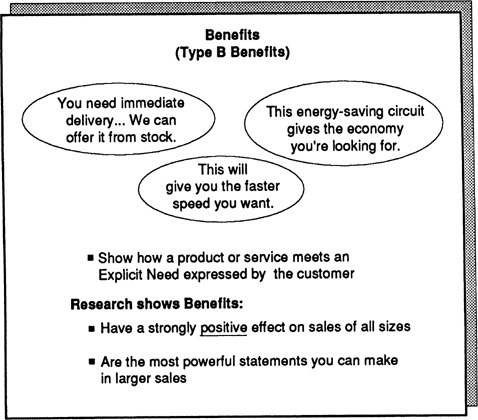

This explains why our research found that Benefits are so much more powerful in larger sales. To make a Benefit, you must have an Explicit Need (Figure 5.6). But in order to get the Explicit Need, you normally must first develop it from an Implied Need by using Implication and Need-payoff Questions. Using Benefits, as we define them, can’t be divorced from the way you develop needs. When my colleagues and I at Huthwaite run training programs, we are often asked for advice on how to use more Benefits. Our reply is simple: “Do a good job of developing Explicit Needs and the Benefits almost look after themselves.” If you can get your customers to say, “I want it,” it’s not difficult to make a Benefit by replying, “We can give it to you.”

Figure 5.6. Benefits (Type B Benefits).

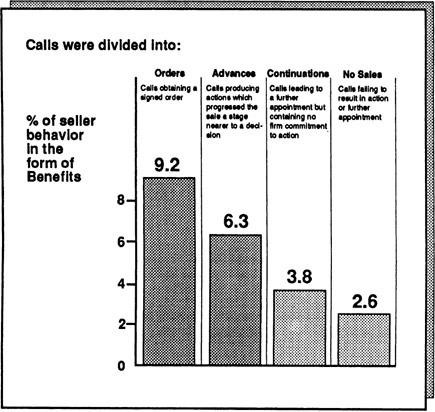

Benefits and Call Success

One of our early studies that confirmed the power of Benefits was carried out in a number of high-technology companies across Europe and North America. We compared the level of Benefits in 5000 calls with the outcome of each call (Figure 5.7). We found that Benefits (and remember that our definition of a Benefit is a statement that shows how you can meet an expressed Explicit Need) were significantly higher in calls leading to Orders and Advances. In contrast, the level of Advantages (showing how your product can help or be used—what many of us have been taught to call “Benefits”) was not significantly different in successful and unsuccessful calls.

Figure 5.7. Relationship of Benefits to outcome in 5000 high-technology calls: Chart shows relationship of Benefits to sales.

Features, Advantages, and Benefits in the Longer Selling Cycle

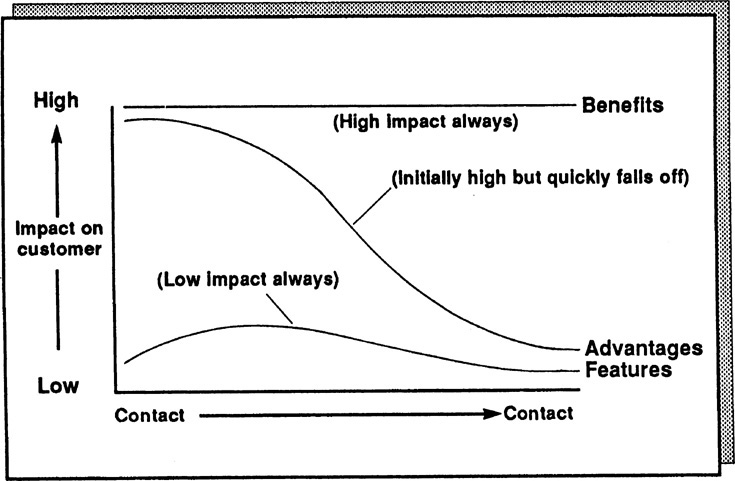

One of the curious findings from our research was that the impacts of Features, Advantages, and Benefits on the customer are not similar throughout the selling cycle (Figure 5.8).

Figure 5.8. Features, Advantages, and Benefits across the selling cycle.

We were working with one of the world’s leading business-machines companies, and part of our investigation involved measuring the effects of sales behaviors at different points in the selling cycle. The average selling cycle in this organization was 7.8 calls long. Company researchers, working with Huthwaite, accompanied salespeople into calls at different points in the cycle. They observed the frequency with which each seller used Features, Advantages, and Benefits and then compared this data with the outcome of each call. To be technical for a moment, the vertical axis of the graph in Figure 5.8 actually shows the significance level of each behavior measured by a battery of nonparametric tests. In simpler terms, the higher a behavior comes on the vertical axis, the more it’s likely to help you sell.

As you can see in Figure 5.8, Features had a low impact on the customer throughout the selling cycle. Benefits, at the other extreme, had a high impact whenever they were used. Advantages had an unusual behavior. We found that early in the cycle, particularly during the first call, Advantages had a moderately good statistical relationship to call success. This is another way of saying that Advantages had a positive impact on the customer during the first call—sellers who used a lot of Advantages were likely to get an Advance rather than a Continuation or No-sale. However, as the cycle progressed, Advantages had a decreasing effect on the customer until, as the end of the cycle approached, they were no more powerful than Features.

Why Do Advantages Run Out of Steam?

To be honest, I’m not sure why Advantages are more effective early in the cycle than late. It’s one of those findings which the Huthwaite research team still argues about whenever we get together. Possibly it’s because, at a first meeting, the customer expects to hear about the product rather than to discuss needs. I’m sure you’ve often made first visits to customers who start off the call by saying “Now tell me all about this product of yours.” I’ve certainly had customers who don’t want to discuss needs until they know more about what I’ve got to offer.

Another possibility is that many of the sellers who jump in early with Advantages do so because they are genuinely enthusiastic about their products. They can’t wait to start talking solutions. In the short term, their enthusiasm carries them along, at least to the point where the customer agrees to proceed to a further step in the selling cycle. However, if they continue a product-centered approach as the cycle progresses, they aren’t responsive to customer needs and therefore become less effective.

A third possibility is that Advantages, as we’ve seen earlier, are very quickly forgotten after the call; Consequently, their effect is temporary. In contrast, Benefits continue to have an impact between calls because their link to Explicit Needs helps customers remember them.

Whatever the reason, I’m sure you’ve seen cases in your own company of this phenomenon in action. A typical example is the pushy, aggressive individual who’s much more interested in selling the product than in meeting the customer’s needs. This kind of person will frequently be very successful in the early stages of the sale. I’m sure you’ve listened, as I have, to the stories these people tell about how they’ve just had a first meeting with a new customer and impressed this customer mightily by the way they put the product across and showed how it could solve all the customer’s problems. But how many of these promising beginnings turn into orders? Fewer than you’d expect. And a very likely reason is that the seller’s high-Advantage style has helped early in the cycle but run out of steam as the sale progressed. But whatever the explanations, the research is giving us a simple but important message. Advantages are less powerful than Benefits all through the selling cycle. It never pays to offer an Advantage if you can go that bit further and offer a Benefit.

Selling New Products

There’s one area of Demonstrating Capability that is generally handled badly, even by experienced salespeople. It happens to be an area vital to most organizations’ success and it’s a source of perennial frustration and disappointment to senior management. The area I’m talking about is the new-product launch. Over and over again, my Huthwaite colleagues and I are asked by top management to help explain why a new product has failed to meet its initial sales target.

“What’s wrong?” they ask. “We were sure our projections were realistic. Yet now, 6 months into the launch, we’re less than 50 percent of plan. Is it the product? Is it the sales force? What’s going wrong?”

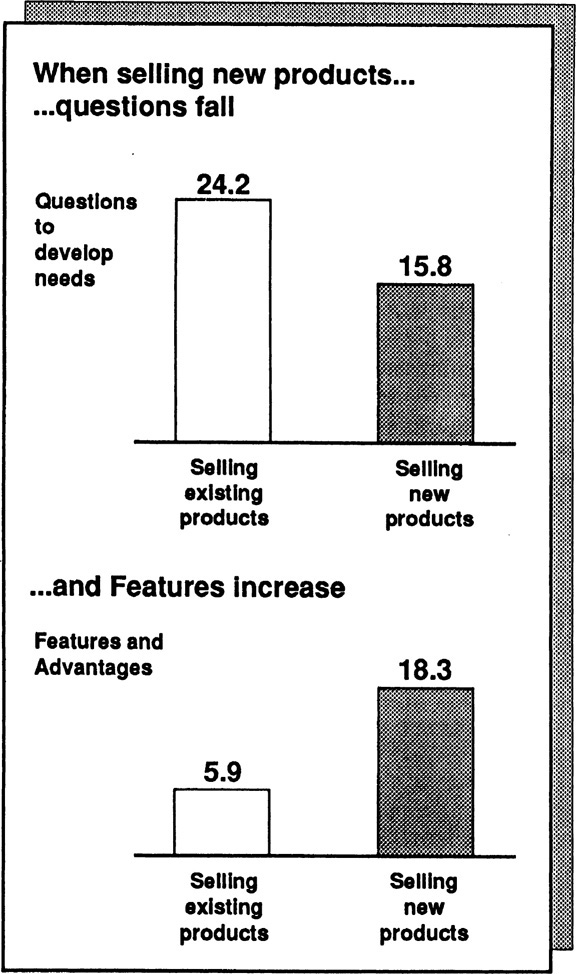

From the many product launches we’ve studied, one constant fact emerges. The biggest single cause of poor results early in a product’s life can be explained in terms of Features, Advantages, and Benefits.

The Bells-and-Whistles Approach

When a product is new, how does product marketing generally communicate it to the sales force? The marketing people call the sellers together and tell them about what an exciting new product is coming. They explain all the Features and Advantages—all the bells and whistles. And what do the salespeople then do? They become excited about the product and go out to sell it. And when they are in front of customers, how do they behave? They communicate the product in exactly the same way it was communicated to them. Instead of asking questions to develop needs, they jump in with all the exciting Features and Advantages that the new product possesses.

Figure 5.9 shows the composite data from a number of product launches. As you can see, the average number of Features and Advantages given when selling new products is more than 3 times the level given by the same salespeople when selling existing products. The evidence suggests that the sellers’ attention is much more on the product than on their customers. To be frank, I’ve done it myself—you’ve probably done the same thing too. Whenever Huthwaite launches a new product, we all get excited and enthusiastic, and we can’t wait to tell our clients all about it. And like so many other companies, we wonder why—despite our enthusiasm—we’re not making sales. We now understand that it’s precisely because of our enthusiasm that we have a problem. Our enthusiasm has led us to become product-centered and to give Features and Advantages. As we’ve seen in this chapter, that’s not an effective strategy for the major sale.

Figure 5.9. When selling new products, the tendency is toward promoting the product, not on customer needs.

The Problem-Solving Approach

We had an interesting opportunity to test whether something as simple as excessive Features and Advantages could really account for the slow growth of new-product sales. A major company in a medical market invited us to carry out an experiment with the launch of one of its new products.

The product was a sophisticated, and expensive, piece of diagnostic equipment. It was clearly in the category of the larger sale. The machine was launched to most of the sales force in the conventional way—a high-key presentation of its Features and Advantages by the product marketing team. But we were allowed to launch it differently with a small experimental group of salespeople. Instead of showing them the product and describing its Features and Advantages, we didn’t even let them see what they would be selling. “It’s not important,” we explained. “What is important is that this machine is designed to solve problems for the doctors who use it.” We then listed the problems the machine solved and the needs it met. Finally, we had our group make a list of accounts where these problems could exist, together with the Problem, Implication, and Need-payoff Questions they would ask when they visited those accounts. By launching the product in terms of the problems it solved and how to probe for them, we were able to shift our small group’s attention away from the product and back to customer needs. The proof that this was an effective strategy is in the sales results. Our group averaged a 54 percent higher level of sales than the rest of the sales force during the product’s first year.

This research on new products also gave me an explanation for something that had puzzled me for many years. Some of the people with the best records for selling new products are the most cynical about product launches. I remember going to a product launch in Acapulco some years ago. The event was splendiferous. Big names from the entertainment world had been hired at unbelievable cost, and the place swarmed with public relations people, media specialists, communications consultants, and a variety of similarly expensive people. The salespeople, eagerly awaiting the great event, filed into the main hall to hear one of the most spectacular and costly Feature dumps of the decade. I was depressed at the enormous expense my client had gone to in order to make the sales force communicate the new product ineffectively, so I decided to wait outside until all the fuss and spectacle subsided. As I sat by the pool, I noticed two other people who had slipped out of the same presentation. Talking with them, I found that they were both very experienced high performers. “It’s just another product,” said one. “When the fuss dies down, I’ll go back in and figure out which customers need it.” Clearly he wasn’t going to fall into the trap of neglecting needs in favor of Features and Advantages.

Have you ever noticed how, just when the new product is proving to be a disappointment and the sales force is losing its enthusiasm, sales suddenly start to improve? I recall exactly that happening when I was involved in the launch of a large new copying machine. At the time I thought it was curious that sales were terrible until the sales force stopped being excited by the new product. Then, at the point where everybody was beginning to say, “This new machine isn’t anything special,” results took a dramatic turn for the better. I couldn’t explain it because it seemed so much the opposite of common sense. You’d think that the machine would be most successful when it was new—with maximum sales-force enthusiasm and maximum competitive lead time. Now I know what was happening. As they became disillusioned, the attention of the salespeople turned away from the product and back to the customer.

There’s a lesson here for anybody concerned with successful product launches. Several of our large multinational clients, on the basis of Huthwaite’s research, now handle launches in a new way. Instead of giving Features and Advantages when they announce new products to the sales force, they concentrate on explaining the problems the product solves and on thinking up the questions that will uncover and develop these problems. It’s proved a very successful method for speeding the growth curve of new-product sales.

Demonstrating Capability Effectively

What are the central messages in this chapter that will help you demonstrate your capability more effectively in larger sales? I would pick out three main practical points:

1. Don’t demonstrate capabilities too early in the call. In smaller sales you can uncover a problem and jump straight in with Advantages about how you can solve it, but this doesn’t work well in larger sales. It’s important in larger sales to develop Explicit Needs—by using Implication and Need-payoff Questions—before you offer solutions. Presenting capabilities too soon is one of the most common mistakes in large accounts. It’s made worse because many customers will encourage you to present solutions in the absence of any information about needs. “Just come and make a presentation about your product,” they tell you, “and we’ll decide whether it fits our needs.” If you’re forced to make presentations of Features and Advantages early in the selling cycle, always try to have a minimum of one premeeting with a key person in the account to uncover needs, so that your presentation includes at least some Benefits.

2. Beware Advantages. Most sales training, because it’s based on models appropriate to smaller sales, encourages you to give Advantage statements when you sell. And to complicate the issue, the term they use for such statements is “Benefits.” Don’t let previous training mislead you. Remember that, in larger sales, the powerful statements are those which show that you can meet Explicit Needs. Don’t fool yourself into thinking you’re giving a lot of Benefits if you’re not uncovering and meeting those Explicit Needs.

3. Be careful with new products. Most of us give far too many Features and Advantages when we’re selling new products. Don’t let this happen to you. Instead, the first thing to ask yourself about any new product is “What problems does it solve?” When you understand the problems it solves, you can plan SPIN questions to develop Explicit Needs. Try it. You’ll be much more effective.

ANSWERS: Types of Product Statements

1. Feature. Balanced voltage stabilization is a fact about the system. The statement doesn’t explain how stabilization can be used or can help the customer.

2. Advantage. This statement shows how the Feature in statement I can be used or can help the customer. It’s not a Benefit because the customer hasn’t expressed an Explicit Need for stabilization.

3. Advantage. The statement shows how backup memory can be used or can help the customer, so it’s more than just a Feature. But because there’s no evidence that the customer has expressed an Explicit Need for backup memory, we can’t call it a Benefit.

4. Feature. Statements of cost (like this one) are facts or data about the product, so we classify them as Features.

5. Benefit. In the previous statement the customer has expressed an Explicit Need: “I need to be able to read source data straight into memory.” In this statement the seller shows how the product meets that Explicit Need.

6. Benefit. Again, the buyer has stated an Explicit Need (an error rate less than 1 in 100,000). The seller shows that his product can easily meet the need.

7. Advantage. The seller shows another way in which having a low error rate can be used or can help the customer. However, as the next customer statement shows, this doesn’t meet a need.

8. Feature. A piece of data about the product.

9. Feature. Further product facts.

10. Advantage. The seller shows how the Feature of time-based coding can be used to help the customer.