3

Customer Needs

in the Major Sale

I suggested in Chapter 2 that success in the Obtaining Commitment stage of the call depends on how well the earlier stages have been handled. Our studies at Huthwaite revealed that the stage with the strongest influence on overall call success is Investigating (Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1. The Investigating stage: Asking questions and collecting data about customers, their business, and their needs.

In our research we consistently found that the people who were most effective during the Investigating stage were the ones most likely to be top sales performers. And poor investigating skills made sellers seem weak in the later stages of the call. Over and over again we’d find that salespeople who were described by their managers as “weak closers” were, in fact, unskilled in Investigating. I’ve always derived a sneaky delight when, after a program we’ve run for salespeople, their managers tell us things like “You really did a great job beefing up Fred’s closing” or “Ann’s now a much stronger closer, so you must have taught her some dynamite techniques.” In fact, we’ve given very little attention to closing. Our main objective in the training has been to improve Investigating skills by teaching people how to develop customer needs using the SPIN questions. And that brings me to the subject of this chapter—customer needs.

As the sale grows in size, customer needs begin to develop in a different way than in small sales. Let me first give you an example of how needs develop in a very small sale. A few months ago I was waiting for a connecting flight in Atlanta. As I wandered through an airport store, a small gadget caught my eye. It was one of those multibladed tools with screwdrivers, a knife, and a device for extracting mysterious objects from unlikely places. It came in a neat little leather pouch and it cost about $15. Within 2 seconds of seeing it I was reaching for my wallet. My need developed all the way from nothing to the point of purchase in a lot less time than it takes you to read this sentence.

In contrast, the first time I bought a computer system there was upwards of a year between initial discussions about our needs and the final decision. It’s in the nature of major sales that needs aren’t instant. They develop slowly and sometimes painfully. Major sales require special selling skills to help this process of needs development—and these skills represent some of the most crucial differences between success in small sales and in large.

Different Needs in Small Sales and Large

Let’s look more closely at my $15 decision and see what it illustrates about needs in the small sale. Clearly the most obvious and dramatic aspect is the faster speed of needs development in smaller sales. But there are other contrasts with larger sales that are worth noting. For example:

![]() It was exclusively my need I was satisfying. I didn’t have to consult with others, as I would almost certainly do in a major sale.

It was exclusively my need I was satisfying. I didn’t have to consult with others, as I would almost certainly do in a major sale.

![]() My need had a strong emotional component. I didn’t have a rational use for the gadget, and it still lies unopened on the back shelf reserved for why-on-earth-did-I-buy-that acquisitions. If I’d thought more carefully, I probably wouldn’t have bought it. Spur-of-the-moment decisions, often irrational ones, are more common in small sales than in large. The emotional component of needs does exist in larger sales, but it’s more subtle and more subdued.

My need had a strong emotional component. I didn’t have a rational use for the gadget, and it still lies unopened on the back shelf reserved for why-on-earth-did-I-buy-that acquisitions. If I’d thought more carefully, I probably wouldn’t have bought it. Spur-of-the-moment decisions, often irrational ones, are more common in small sales than in large. The emotional component of needs does exist in larger sales, but it’s more subtle and more subdued.

![]() If I’d make a bad purchase that didn’t really meet my needs, the worst thing that could happen would be the loss of $15. In contrast, a bad purchasing decision in a major sale could cost me my job.

If I’d make a bad purchase that didn’t really meet my needs, the worst thing that could happen would be the loss of $15. In contrast, a bad purchasing decision in a major sale could cost me my job.

A $15 purchase is, of course, tiny even in terms of small sales. But it illustrates some key differences between needs in small sales and in large. Broadly speaking, we can say that as the sale becomes larger:

![]() Needs take longer to develop.

Needs take longer to develop.

![]() Needs are likely to involve elements, influences, and inputs from several people, not just the wishes of a single individual.

Needs are likely to involve elements, influences, and inputs from several people, not just the wishes of a single individual.

![]() Needs are more likely to be expressed on a rational basis, and even if the customer’s underlying motivation is emotional or irrational, the need will usually require a rational justification.

Needs are more likely to be expressed on a rational basis, and even if the customer’s underlying motivation is emotional or irrational, the need will usually require a rational justification.

![]() A purchasing decision that doesn’t adequately meet needs is likely to have more serious consequences for the decision maker.

A purchasing decision that doesn’t adequately meet needs is likely to have more serious consequences for the decision maker.

Are these differences substantial enough to require different questioning skills when you’re developing needs in a larger sale? Our research suggests that they are. We found that some of the probing techniques that were very successful in smaller sales failed entirely in larger ones.

In order to understand why questioning skills are different in larger sales, we must first be clear about the stages through which needs develop. Let’s begin with a definition of what we mean by need. In our research, we defined a need as:

Any statement made by the buyer which expresses a want or concern that can be satisfied by the seller.

Incidentally, some writers have made great play of the distinction between a need and a want. A need, they say, is an objective requirement—you need a car because there’s no other form of transport that will get you to work. A want, on the other hand, is something that has personal emotional appeal—you want a Rolls Royce, but this doesn’t mean that you need one. We found this distinction unhelpful, particularly in larger sales. When we refer to the term need, we use the word in a broad sense. Our definition includes both the needs and wants that the buyer expresses.

How Needs Develop

A potential buyer who genuinely feels 100 percent satisfied with the way things are doesn’t feel any need to change. What’s the first sign—in any of us—that we have a need? Our 100 percent satisfaction with the existing situation becomes a 99.9 percent satisfaction. We can no longer genuinely say that we feel absolutely content with the way things are. So the first sign of a need is a slight discontent or dissatisfaction.

A few months ago, for example, I could honestly say that I was completely satisfied with the word processor I’m using to type this book. I had no need, and if you were selling word processors, I’d have been a wasted call. However, while writing this, I’ve become more aware of a few small imperfections. The automatic spelling check is cumbersome to use. Certain editing functions are a little complicated. My dissatisfaction isn’t large, but it is there. I’m still not a good prospect for a new word processor, but the inevitable seeds of change are germinating—dissatisfaction exists and it’s likely to grow.

What will happen next? Most probably it will gradually become clear to me that the editing limitations are a real nuisance. I’ll perceive significant problems and difficulties, not just a minor dissatisfaction. And at this point it will become very much easier for somebody to interest me in a new machine.

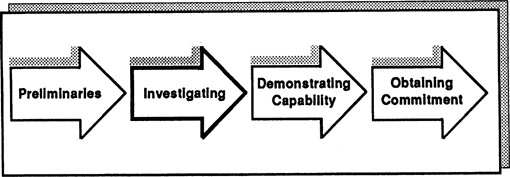

But my perception of a problem, even if the problem is severe, doesn’t mean I’m ready to purchase. The final step in the development of a need is for the problem to be translated into a want, a desire, or an intention to act (Figure 3.2). I’m not going to buy a new word processor until I want to change. And when this happens, I’m ready to buy.

Figure 3.2. Developing needs.

So we can say that needs normally:

![]() Start with minor imperfections.

Start with minor imperfections.

![]() Evolve into clear problems, difficulties, or dissatisfactions.

Evolve into clear problems, difficulties, or dissatisfactions.

![]() Finally become wants, desires, or intentions to act.

Finally become wants, desires, or intentions to act.

In small sales, as we’ve seen, these stages can be almost instantaneous. In larger sales the process may take months or even years.

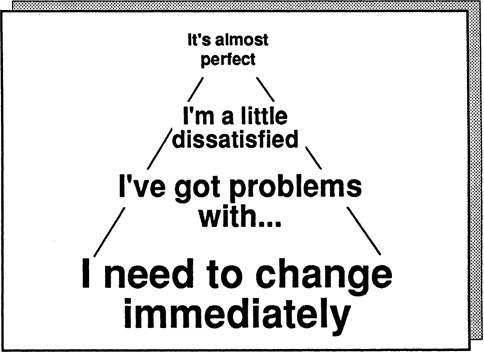

Implied and Explicit Needs

As we began to research customer needs at Huthwaite, we looked for a simple way to express this series of stages. We decided to divide needs up into two types (Figure 3.3):

Figure 3.3. Implied and Explicit Needs.

Implied Needs. Statements by the customer of problems, difficulties, and dissatisfactions. Typical examples would be “Our present system can’t cope with the throughput,” “I’m unhappy about wastage rates,” or “We’re not satisfied with the speed of our existing process.”

Explicit Needs. Specific customer statements of wants or desires. Typical examples would include “We need a faster system,” “What we’re looking for is a more reliable machine,” or “I’d like to have a backup capability.”

In this way we were able to take the continuum of needs and simplify it into just two classes, Implied and Explicit.

I’m always suspicious of people who introduce new jargon terms. If I’d been reading this chapter, I’d have asked myself questions like: What’s the point of dividing needs up into Implied and Explicit? Doesn’t it just introduce an unnecessary complication? How’s it going to help me sell? These are fair questions, and they have an important answer. Our research suggests that in small sales the distinction between Implied and Explicit Needs isn’t crucial for success. But in larger sales, one of the principal differences between very successful and less successful salespeople is this:

![]() Less successful people don’t differentiate between Implied and Explicit Needs, so they treat them in exactly the same way.

Less successful people don’t differentiate between Implied and Explicit Needs, so they treat them in exactly the same way.

![]() Very successful people, often without realizing they’re doing so, treat Implied Needs in a very different way than Explicit Needs.

Very successful people, often without realizing they’re doing so, treat Implied Needs in a very different way than Explicit Needs.

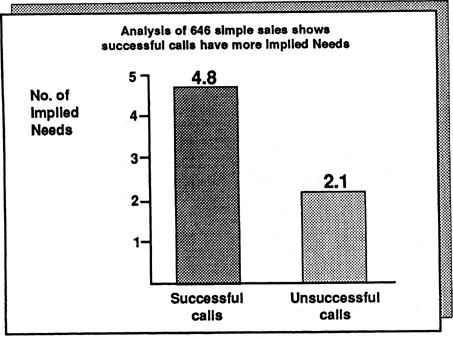

Let’s look at some research evidence. In one of our studies we tracked 646 simple sales, counting how many times the customer stated an Implied Need during the call. Figure 3.4 shows the results. The successful calls contained more than twice as many Implied Needs as the unsuccessful calls. This suggests that, in simple sales, the more Implied Needs you can uncover, the better your chance of getting the business. Confirmation of this comes from another study that we carried out with a large office products company. The company was divided into two divisions, one selling simpler low-end products and one concerned with larger major sales. In the division selling low-end products, when a group of salespeople was trained to uncover more Implied Needs, its sales went up by 31 percent compared with those of an untrained control group. So it’s fair to say that, at least in smaller sales, the more Implied Needs you can uncover, the greater your chances of success.

Figure 3.4. Implied Needs predict success in simple sales.

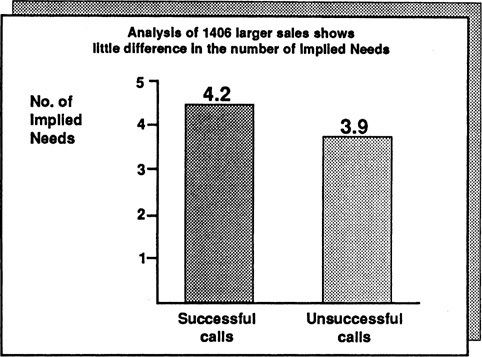

But what about larger sales? Is the same thing true there? No, it’s not. As the sale becomes larger, the relationship between Implied Needs and success diminishes (Figure 3.5). In one of our studies, we analyzed 1406 larger sales, where the average contract size was $27,000. We found that—unlike small sales—there was no relationship between the number of Implied Needs the seller uncovered and the success of the call. Implied Needs are buying signals in small sales, but not in large.

Figure 3.5. Implied Needs do not predict success in larger sales.

What does this mean? Our interpretation is that, in larger sales, the sheer quantity of Implied Needs—or customer problems—that you uncover doesn’t have much influence on the outcome of the call. Instead, Implied Needs are just a starting point, the raw material that successful salespeople use as part of their needs-development strategy. What matters in the larger sale isn’t the number of Implied Needs you uncover, but what you do with them after you’ve uncovered them. As an example of this, in the high-end sales division of the office products company, we carried out a test whereby we were able to increase the sales of 49 people by 37 percent compared with a matched control group. Yet unlike their low-end colleagues, these salespeople’s success was unrelated to the number of Implied Needs they uncovered.

Why Implied Needs Don’t Predict Success in Larger Sales

When pocket calculators were first introduced, they were offered for sale at a trade show. There was an incredible response. The manufacturer, who had brought 1500 calculators to the booth, had sold every one in less than 2 hours. Hundreds of potential customers had to be turned away. Why was the new calculator so successful? Because it created instant dissatisfaction with the sheer bulk and inconvenience of large desk calculators. In other words, it generated an immediate Implied Need. But there was another equally important factor. The new calculator also represented a real price breakthrough, being less than one-fifth the cost of the cumbersome adding machines it was designed to replace. So visitors to the trade show had a twin incentive to purchase; they had Implied Needs (or dissatisfactions with their existing adding machines) and an amazingly low cost for the new replacement. Combine these two points and it’s easy to see why people were lining up to buy.

But what would have happened if the new calculators had been 5 times the price of a mechanical adding machine instead of just one-fifth? Would there still have been the same rush to buy? Almost certainly not. The reason why the calculators were so attractive was that they offered such good value. In other words, they gave buyers a lot of capabilities for very little money.

Anyone making a decision to purchase must balance two opposing factors. One of these factors is the seriousness of the problems that the purchase would solve. The other is the cost of the solution. In the case of the calculators, as in many small sales, because the cost was so low it was easy for relatively superficial needs to tip the balance in favor of purchase.

The Value Equation

One way to think about the relationship between the size of needs and the cost of a solution is the concept of the value equation. As Figure 3.6 shows, if the customer perceives the problem to be larger than the cost of solving it, then there’s probably a sale. On the other hand, if the problem is small and the cost high, then there’s unlikely to be a purchase.

Figure 3.6. Value equation: If the seriousness of the problem outweighs the coast of solving it, there is a basis for a successful sale.

The price of a product or service is usually lower in simple sales. As a result, the size of the perceived needs on the other side of the equation doesn’t have to be so great. That is, the Implied Needs may be quite sufficient to justify a purchase in the case of a small decision, such as buying the calculator. But if the calculator had cost more than conventional adding machines, then the need would have to be correspondingly bigger to justify a purchase.

This explains why you can sell successfully in smaller sales, where the cost of the solution is generally low, just by uncovering problems, or Implied Needs. And it also explains why, in major sales, you must develop the need further so that it becomes larger, more serious, and more acute in order to justify the additional cost of your solution. Remember that in larger sales the cost isn’t measured only in terms of money. As I said earlier, a bad decision can cost the buyer’s job. The buyer often perceives significant risks and hassles (which can’t be measured in cash terms) as adding to the cost side of the value equation.

Explicit Needs and Success

If it’s true that the need has to be bigger to justify a more costly solution, then you’d expect that success in larger sales might be much more closely related to the number of Explicit Needs in the call than to the number of Implied Needs. This is easy to test.

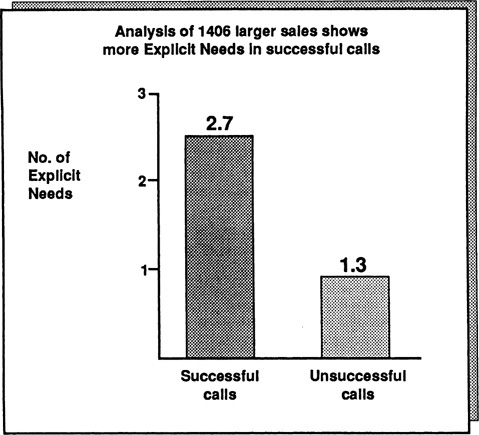

In the study of 1406 larger sales that I cited earlier, we also recorded the number of times the customer expressed an Explicit Need—which you’ll remember is a specific statement of a want or desire that the seller’s product can satisfy. As Figure 3.5 showed, the Implied Needs were not significantly higher in the successful calls. As Figure 3.7 shows, however, the Explicit Needs were twice as high in the calls that succeeded. This data confirms that, as the sale grows larger, it becomes increasingly important to obtain Explicit Needs, not just Implied Needs.

Figure 3.7. Explicit Needs and success in larger sales.

So, in larger sales, Implied Needs don’t predict success, but Explicit Needs do. In smaller sales, both Implied Needs and Explicit Needs are success predictors. What does this mean in terms of your questioning strategy? In the smaller sale, a strategy that uncovers problems (Implied Needs) and then offers solutions can be very effective. In larger sales this is no longer the case. A probing strategy for the larger sale must certainly start by uncovering Implied Needs, but it can’t stop there. Successful questioning in the larger sale depends, more than anything else, on how Implied Needs are developed—how they are converted by questions into Explicit Needs.

Buying Signals in the Major Sale

Most people in selling are familiar with the concept of buying signals, statements made by the customer that indicate a readiness to buy or to move ahead. Implied Needs are accurate buying signals for small sales; the more times a customer agrees to a problem or difficulty, the more likely the sale. In contrast, Explicit Needs are the buying signals that predict success in larger sales. We’ve observed that as salespeople grow more experienced, they usually give more weight to Explicit Needs as buying signals in judging how successful a call has been. Less experienced people put too much weight on Implied Needs.

For example, here’s an inexperienced seller in the telecommunications industry. Notice how he puts great emphasis on the Implied Needs he has uncovered as evidence that the sale has advanced.

INTERVIEWER: ... so you’d say the call was successful?

SELLER: Yes, I think so.

INTERVIEWER: Was there anything the customer said—buying signals, for instance—that made you feel it was a success?

SELLER: Yes. He agreed that he had a capacity problem during morning peaks.

INTERVIEWER: Anything else?

SELLER: He’s not happy about the quality of the data transmission.

INTERVIEWER: And on the basis of these “signals,” you’d say that it’s been a successful call?

SELLER: I think so. After all, we can help him with both of those problems. I’d think there’s a good chance of some business.

Here, the seller judges the call as successful because the customer raised two problems, or Implied Needs. But as discussed earlier, there’s no relationship between the number of problems you uncover in a large sale and whether the customer will ultimately buy from you. In this case the seller was surprised and disappointed to find, 2 weeks later, that the customer was talking to a competitor who, a few months later, successfully took the business.

In contrast, let’s hear how a very successful seller from the same sales organization judges call success. She’s one of the top five performers in her region, which contains over 400 salespeople.

INTERVIEWER: Was this a successful call?

SELLER: Difficult to tell. I found a few problems we could solve, but until I’ve had a chance to go back and develop them more, I’d prefer to hold judgment on whether we’re going to get anywhere.

INTERVIEWER: Does that mean you don’t see the problems you uncovered as “buying signals”?

SELLER: Indirectly they are, I guess. After all, you don’t get anywhere unless you find some problems you can handle. So no problems means no sale—and that’s a kind of negative signal—those are the worst calls. But I wouldn’t really say that problems are positive buying signals.

INTERVIEWER: In general, what are the buying signals that tell you a call’s successful?

SELLER: It’s when you hear the customer talking about action. Things like “I’m going to overhaul our data network next year” or “We’re looking for a system with these three characteristics.” It’s things like that.

INTERVIEWER: You know about the difference between Implied and Explicit Needs. It sounds like you’re saying that Explicit Needs are a better signal than Implied Needs. Would that be right?

SELLER: Yes. You can’t just rely on problems, you’ve got to have something stronger. That’s why I think that the big skill in selling isn’t so much getting the customer to admit to problems. Almost everyone I call on has problems, but that doesn’t mean they’ll buy. The real skill is how you grow those problems big enough to get action. And when the customer starts talking about action, that’s when I hear “buying signals.”

Here, unlike the inexperienced person, the seller puts little faith in problems or Implied Needs. Instead, her focus is on what she calls “actions.” The examples she offers are what, in our terminology, we would call Explicit Needs. Like most of the very successful people we worked with, this seller puts strong emphasis on needs development as the most important selling skill.

I suggested in Chapter 2 that developing needs is the key function of questions. In terms of the larger sale, we can now express this more precisely:

The purpose of questions in the larger sale is to uncover Implied Needs and to develop them into Explicit Needs.

In the next chapter I’ll show how this can be done using the SPIN questions.