Chapter 3

The Alien in Your Chest

Compound interest can be your best friend or your worst enemy. It is a two-edged sword—far more powerful than you thought.

Do you remember the gut-wrenching moment in the movie Alien when the horrible creature that had been quietly growing inside one of the spaceship crewmen suddenly bursts out of his chest? When I first saw that, my first thought was of compound interest on consumer debt. What is compound interest? It's interest earned or charged on top of interest, and, like fire, it is a powerful servant but a fearful master. Why is it like the monster bursting out of the spaceman's chest? Because that's what consumer debt does when your job is threatened in a recession, or when you wake up one day and find that your debt has grown until you cannot service it out of your income.

Compound interest is probably the main reason you won't ever be financially secure. Many corporations have become giants because of compound interest earned at your expense. It has burrowed deep into the lives of millions of families and individuals and quietly gnawed away at their substance 24/7—even while they slept—painlessly and surreptitiously eating their paychecks even before they were earned. Then, when these people are laid off in a recession or over-committed and can't meet their compounding-by-the-second debt service, it can burst out in the form of creditor calls, sleepless nights, daymares, and irresponsible behavior they would never engage in if it were not for their debts.

Much of the money I don't have was lost because I arrogantly ignored my own rules for borrowing. Money already committed for paying compound interest for consumer debt is not available for earning compound interest for the future. I have evolved (usually the hard way) some inexorable rules, including some you may not have heard before, that you must never violate if you want to convert compound interest from your mortal enemy into your best friend.

The first step in doing that is to accumulate a nest egg out of current income by redirecting the money you are now paying out in compound interest on your debts into savings that will pay you compound interest instead. This will turn the power of compounding into your servant instead of the wealth-destroying master it is now.

So far, I probably haven't startled you with the novelty of my wisdom, but that is probably because you have no clue as to the power of this mathematical phenomenon. Albert Einstein, who is rumored to have known something about mathematics, said, “The most amazing mathematical phenomenon is the magic of compounded interest.” Let's examine why.

THE INVISIBLE PROSPEROUS PEOPLE IN YOUR NEIGHBORHOOD

There are financially secure people—even millionaires—in your own backyard. They live in nice but modest homes, drive nice but modest cars, live very comfortably, are financially and emotionally secure and debt-free, and a lot better off than you might suppose. Bill Gates is not their kind of guy; they didn't make a big killing in the stock market or invent a super widget that everyone had to have. They took no risks and lost no sleep. They didn't even work hard at building their estates. They just quietly, year after year, used the magical power of compounding to build their fortunes. They are the Safely Prosperous. Compound interest is their friend, and they are on the right side of this powerful force.

Then there are some of your other neighbors that you may envy because they seem so successful. They may also live in nice houses and have nice cars—maybe even a ski boat—in their driveway, but they are living lives of quiet desperation. They have no savings and lose a lot of sleep worrying about their bills, and they are only one missed paycheck away from bankruptcy. And their marriages are battlegrounds—usually over money. Even while they sleep, compound interest is gnawing away at their wealth and their future income. Even a big raise or promotion only enables them to run in place a little faster so they can have a newer, more luxurious car and keep up the illusion of prosperity. Compound interest is their enemy, and they are on the wrong side of it!

COMPOUND INTEREST AS A FRIEND

Richard Russell is the newsletter publisher colleague I respect the most, and he is highly regarded on Wall Street. He is a wise, balanced, real adult who has been around a long time and seen it all, and shares most of my old-fashioned values. Not too long ago he wrote the most popular, most requested article he has published in 40 years of writing. It makes my point better than I could, so I obtained Dick's permission to reprint most of it here.

Making money is not just starting a business, winning a lottery or a big NBA contract, predicting which way the stock or bond markets are heading, or trying to figure which stock or mutual fund will double over the next few years. For the great majority of investors, making money requires a plan, self-discipline and desire. I say “for the great majority of people” because if you're a Steven Spielberg or a Bill Gates you don't have to know about the Dow or the markets or about yields or price/earning ratios; you're a phenomenon in your field, and you're going to make big money as a by-product of your talent and ability. But this kind of genius is rare.

For the average investor, you and me, we're not geniuses so we have to have a financial plan. In view of this, I offer below a few principles that we must be aware of if we are serious about making money.

One of the most important lessons for living in the modern world is that to survive you've got to have money. But to live (survive) happily, you must have love, health (mental and physical), freedom, intellectual stimulation—and money. When I taught my kids about money, the first thing I taught them was the use of the “money bible.” What's the money bible? Simple, it's a volume of the compounding-interest tables.

Compounding is the royal road to riches. Compounding is the safe road, the sure road, and fortunately, anybody can do it. To compound successfully you need the following: perseverance to keep you firmly on the savings path; intelligence to understand what you are doing, and why; and knowledge of the mathematics tables in order to comprehend the amazing rewards that will come to you if you faithfully follow the compounding road. And, of course, you need time—time to allow the power of compounding to work for you. Remember, compounding only works through time.

But there are two catches in the compounding process.

The first is obvious—compounding may involve sacrifice (you can't spend it and still save it).

Second, compounding is boring—b-o-r-i-n-g, or should I say it's boring until (after seven or eight years) the money starts to pour in. Then, believe me, compounding becomes downright fascinating!

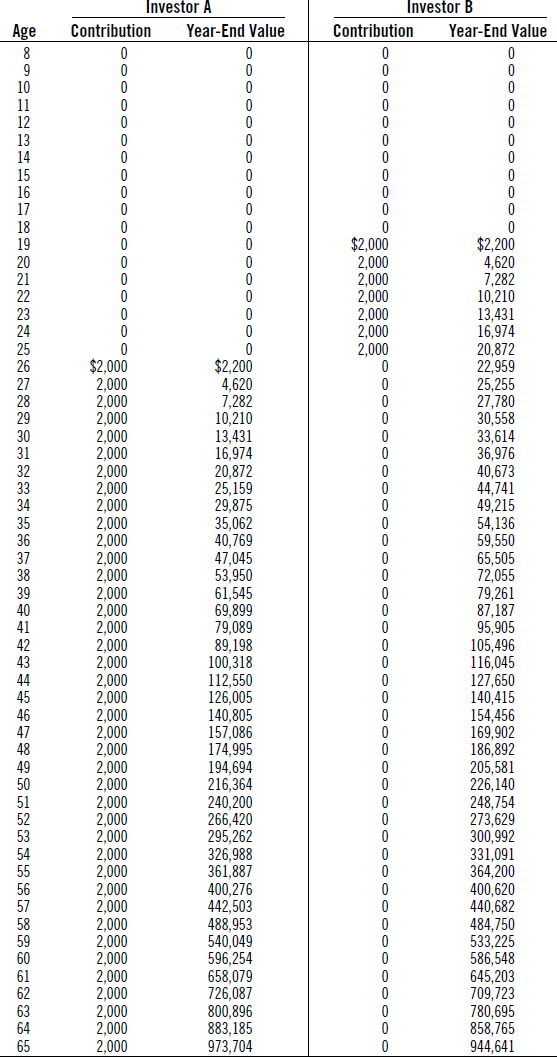

Table 3.1 The Power of Compounding, Part I

In order to emphasize the power of compounding, I am including this extraordinary study [Table 3.1], courtesy of Market Logic of Fort Lauderdale, Florida 33306.

In this study we assume that investor B opens an IRA at age 19. For seven consecutive periods he puts $2,000 in his IRA at an average growth rate of 10% (7% interest plus growth). After seven years, this fellow makes NO MORE contributions—he's finished.

A second investor (A) makes no contributions until age 26 (this is the age when investor B was finished with his contributions). Then A continues faithfully to contribute $2,000 every year until he's 65 (at the same theoretical 10%).

Now study the incredible difference between B who made only seven contributions but made them earlier, and A who made 40 contributions but at a later time. The difference is that B had seven more years of compounding than A, simply because he started earlier. Those seven early years were worth more than all of A's thirty-three additional contributions combined. [Richard's lesson? Start today.]

This is a study I suggest you show to your kids. It's a study I've lived by, and I can tell you, “It works.” You can work your compounding with muni bonds, with a good money market fund, with T-bills or five-year T-notes.

Let me interrupt Dick for a moment.

The amazing thing about his example is the small amount necessary to invest in order to achieve these results. The total net earnings weren't the real difference—$893,704 for investor A against $930,641 for investor B. But the out-of-pocket amounts invested were wildly different—$80,000 over 39 years for investor A, earning an 11-fold return, against only $14,000 over only seven years for investor B, earning a 66-fold return!

Because of compound interest, careless spending has a hidden cost. Due to the lost compounding, every dollar bill spent today for consumer goods or for compound interest on your consumer loans, instead of being invested to earn compound interest, could cost you as much as $20 at retirement time, depending on how many years until retirement. Borrowing at compound interest in order to buy things you could not otherwise afford devours your substance into the foreseeable future.

I have worked out a few more examples of the power of compounding to drive home the point. If you put aside only $40 a month, compounded yearly, and invest it at 8 percent, you will be astounded at how much richer you will be in the future:

After 5 years, you will have $2,980.

After 15 years, you will have $15,034.

After 20 years, you will have $24,763.

After 30 years, you will have $59,480.

If you blow $300 twice a year in Las Vegas for transportation, beer, smokes, or the slots, you just kissed off $71,397 thirty years from now.

Now, back to Dick.

[The typical investor] doesn't comprehend the power of compounding, and he doesn't understand money. He's never heard the adage, “He who understands interest earns it. He who doesn't understand interest pays it.”

But here's the irony; if from the beginning the little guy had adopted a strict policy of never spending more than he made, if he had taken his extra savings and compounded it in intelligent, income-producing securities, then in due time he'd have money coming in daily, weekly, monthly, just like the rich man. The little guy would have become a financial winner, instead of a pathetic loser.

So what investments can safely compound your money? As you consider these possibilities, remember that compounding by its very nature means earning interest on your interest. It requires that the interest be reinvested. It is important to maintain your stream of income from salary or business profits to live on as long as possible so you won't have to spend your interest until your estate is meeting your financial objectives and is earning enough interest to meet your needs—and, yes, your wants.

CHANGING OUTGO INTO INCOME

The first alternative is by far the simplest and offers the greatest guaranteed return. This can help anyone with a savings account, but it is especially useful for those who already have savings invested in low-interest bank deposits and money-market funds.

Let's say you have a 2 percent savings account and a 24 percent credit-card balance. If you pay off the credit card with the savings money, it's the functional equivalent of switching from a 2 percent investment to a 24 percent investment. It's the biggest riskless yield you can get anywhere. And there are other choices:

- Some “safe” investments offer no chance of either capital loss or profit—just a slow, steady, dependable, guaranteed yield and a guaranteed principal. These include bank savings accounts, T-bills, money-market funds, and mortgages. The bank and the money market fund will automatically reinvest your interest, making compounding easy and automatic. The downside? The yields can be very low (less than 1 percent as this is written) and, after taxes and inflation, offer a smaller return—even a negative real return—although these rates will not stay low forever. However, with T-bills and mortgages, you will have to actively put the interest immediately back to work earning interest to get the benefit of compounding.

- Some investments, such as Treasury notes, Treasury bonds, and corporate and municipal bonds, offer a fixed return and higher yield (around 4.5 percent as this is written) with safety of principal but with a chance of capital gains or losses. These investments are all interest rate-sensitive, meaning that your principal can fluctuate up and down in market value as interest rates fluctuate. Generally speaking, when interest rates in the marketplace are rising, these investments tend to fall in value. When interest rates are falling, they tend to rise in value, and can even be more profitable than stocks. Let me explain why.

If you bought a $1,000 10-year Treasury note yielding 5 percent, you would get a guaranteed $50 a year in interest for the life of the note—no more, no less—and when it matured, you would not only have earned your interest, you would also get your $1,000 back. T-notes are risk-free if held to maturity.

However, if market interest rates rose to 10 percent, your note with a fixed contractual return of $50 a year would only be half as attractive to a buyer as a newly issued note paying 10 percent a year, or $100. Many people think that if you buy a 10-year T-note you have to hold it for 10 years until it matures, but that's not so. There is an active, liquid market for T-notes accessible through any broker, so you could sell the note whenever you wanted; but when market interest rates were higher than your yield, the note would have to sell at a big discount (as much as 50 percent) to make the effective yield competitive for the new buyer.

To illustrate this point, let's say that when interest rates were high, such as in 1981, you bought a T-bond yielding 14 percent—paying $140 a year. Interest rates subsequently fell to 7 percent just a handful of years later, so this bond as much as doubled in market value, as it was now yielding twice as much as a newly issued T-bond. This, of course, was affected by how close to maturity the bond was.

Even though the rule is pretty simple, let me say it again: When interest rates go up, note and bond prices go down, and when interest rates go down, note and bond prices go up. But whatever the investment, the interest, dividends, or capital gains must be reinvested, not spent, or there will be no compounding. Failure to compound can mean hundreds of thousands of dollars less when you are about to retire.

So, buy fixed-return debt instruments only when interest rates are rising, high and stable, or trending down, unless you are positive you will hold it to maturity. Lock in the high rates and compound them by reinvesting the earned interest, and enjoy some potential capital gains as well.

One of the most profitable calls in my quarter century as a financial editor and publisher occurred in 1981. After several years of steadily rising interest rates, new 30-year T-bonds were yielding a historic high of 16 percent. I believed interest rates would fall as low as 7 percent, so I urged my subscribers to buy 30-year T-bonds. We not only locked in juicy all-time-high yields, but a few years later when rates on newly issued T-bonds fell to 7 percent, we sold and reaped capital gains as high as 100 percent, in addition to our terrific interest. This “conservative” investment was much more profitable than even the most profitable stocks over the same period, with no risk of losing the capital.

The nice thing about investing in government securities is its simplicity; with stocks, you always have to evaluate the business prospects for the individual company and its industry group as well as the market as a whole. With corporate and municipal bonds (munis), you also have to worry about the credit rating of the issuer, as a drop in the credit rating by the organizations that rate them means an instant drop in value, and most of the credit surprises are to the downside. With Treasury securities you only have to worry about the trend of interest rates. But that's what guys like me are for.

Munis do have one great advantage over T-bonds—the interest is tax-free. But this tax advantage can be shared by T-bonds if you buy them for your IRA or 401(k) or other tax-free or tax-deferred savings account. And the interest on T-bonds or notes is not subject to state taxes.

A VARIETY OF CHOICES

As this is written, most people assume they can't get more interest than the pittance of less than 1 percent they can currently earn in a bank passbook account or a money market fund. But there are always lots of alternatives for decent yields of as much as 20 percent with reasonable risk. We will explore some of these choices in Chapter 5. They are only for-instances in a changing world and may not be good choices by the time you read this, but they are a great place to start looking, and there are always such opportunities, regardless of what the banks are paying.

I have little sympathy for those who complain about low passbook rates just because they are too lazy to dig a little bit for the luscious rates that are always there to be found with a little work. It takes at least 6 percent to make compound interest your real friend, and that's always doable.

WHAT TO DO ABOUT RISING RATES

So now you know what to buy when interest rates are falling or staying low, but what do you invest in when interest rates are rising? That's easy: a money-market fund. These funds invest your money in very short-term notes and bills, ranging from T-bills maturing in as little as 30 days to short-term (even overnight) commercial paper. As interest rates rise, the funds are rolling over their entire portfolios in as little as 30 days into paper paying increasingly higher interest rates, and most of that is passed on to your account, so you benefit from rising interest rates. Money-market funds have one other big advantage: You can start a money-market fund account with as little as $100 and keep saving until you have enough money to buy a bond or a T-bill or T-note when the time is right.

In summary, anyone can benefit from compounding, and total returns around 10 percent (interest and capital gains) can be earned year after year, even when interest rates are generally low. All it takes is a little discipline and the ability to keep your eyes firmly fixed on the future. Let me illustrate that principle with a true story.

When I was getting my pilot's license, my instructor would tell me to fly straight and level at a certain compass heading and altitude. That was easier said than done. I found myself wandering all over the sky—up 300 feet, down 200 feet, or with the nose of the plane swinging as much as 10°, 15°, or 20° to one side or the other while I switched attention from the altimeter to the compass or vice versa. Then my instructor gave me some very wise advice that has been useful in other areas of my life. He said, “Point the nose of the plane on the compass heading you want to fly, and then pick out the farthest landmark that you can see straight ahead—a mountain, a pass, a building—and keep your eyes on it and fly toward it.” To my amazement, the plane settled down, and straight and level became automatic and natural.

So how does this apply to the subject at hand? Keeping your eye on the long-term objective will help you to avoid the bad short-term decisions that can cost you hundreds of thousands of dollars at retirement time.

NIBBLED TO DEATH BY DUCKS

Your personal balance sheet is probably pathetic compared to those of the truly prosperous people in your neighborhood; however, the erosion of your potential wealth by doing stupid things didn't happen all at once. It was a lifelong process, sort of like being nibbled to death by ducks. You have probably been nickel-and-diming yourself to death.

I have now taught you the importance of compounding your money, but how will you get the money to start saving and compounding? That's easy: Become a plumber and plug the leaks!

DOING YOUR OWN PLUMBING: BIG LEAK #1

First, you are destroying your future with the really big leak—compound interest payments on charge accounts, car loans, and credit cards. But even with a sudden rush of frugality, it may still be a while until you are far enough out of debt to be able to divert much of that interest money into a savings program to convert compounding from a ravening monster of an enemy into a faithful but powerful servant. So where can you start accumulating some money now to begin to get on the right side of compound interest, as it's obvious that time is of the essence?

THE WAGES OF SIN: BIG LEAK #2

You could change a few things right now with very little pain that could make a five- or six-figure difference in 20 or 30 years. Here are some cold hard numbers.

Alcohol

The average American family drinks two six-packs of beer and/or a dozen bottles of soda a week. This costs you at least $9 a week, or $35 a month. If you gave up the brew and started putting that $35 a month into an interest-bearing account at only 8 percent, you would have $23,096 in 20 years. Unless you are a chronic alcoholic, this involves only the most minor inconvenience or sacrifice.

I don't know just how much I have saved over 46 years of marriage by being a teetotaler, when I take my wife out to dinner and don't order wine, but it's a lot—a whole lot.

Smoking

Let's assume you have a one-pack-a-day habit. That means you are spending $4 a day, or $120 a month. If you had invested that in a money-market fund at only 6 percent, you would have—are you sitting down?—$70,682 in 20 years! And you are much more likely to be alive to enjoy it because you probably wouldn't have died of lung cancer, emphysema, a heart attack, or some other painful and loathsome disease. Yes, a real nicotine habit is hard to kick, and you may have made dozens of false starts, but maybe I have just given you a serious financial incentive to kick an expensive, dirty habit.

But what if you have no expensive vices to repent of? Is saving money hopeless?

CREATING SAVINGS OUT OF NOTHING

I know women who save their families $20 or $30 a month just by clipping coupons, learning to change their own oil, or sewing or mending the family clothing. That's enough to make a real start on building some real wealth through compounding.

How about going out to eat at an inexpensive Chinese or Thai restaurant every other date night instead of some ritzy joint where the food tastes no better and costs two or three times as much? You will save $20 to $40 bucks twice a month.

How about waiting until the biggest hit movies come to the local dollar theater or on video, instead of paying the $9 regular admission for each of you? That's worth about $35 to $70 a month.

There is hardly a family in America that couldn't save and put away 20, 30, or 50 bucks every month. They just need a clear picture of their long-term goals and a grasp of the power of compounding and the financial rewards of even a modicum of self-control and personal discipline.

Here are a few more suggestions gleaned from The Wall Street Journal.

Trim Your Insurance Bill

Stay clear of expensive whole life insurance, and buy cheaper term insurance instead, at least until your newfound prosperity makes it worthwhile to take advantage of the tax benefits whole life can provide. As you near retirement, reduce your coverage to lower your premiums; you don't need as much coverage as a young wage earner with dependent children. You can save the difference and earn compound interest on the money.

Redirect Your Education Dollars

Fifty-year-old people usually no longer have to spend money on education as the kids graduate from college. Invest the money and create a compounding cash cushion for yourself.

TAX-FREE SAVINGS

Because your plan can be aborted by taxes on your interest and other investment returns, cutting the money available to compound, you have to seriously consider putting as much of your savings as possible into a tax-exempt or tax-deferred account, such as an IRA or a 401(k). This can make a huge difference over time. Consider the following.

Stocks and Bonds

The real optimists assume there will be an average annual return of 8 percent in the stock market over time. I think that's a dubious proposition, but let's accept it for the sake of discussion. After you have paid 1.5 percentage points for taxes, your yield is down to 6.5 percent. Then knock off another 3.5 points for inflation and investment costs. You are now down to only 2 percent a year in a best case. If you dodge the taxes in an IRA, the real return is 3.5 percent. Not humongous, but still worth compounding.

With bonds, the results are more predictable because, unlike the case with stocks, the returns are guaranteed and riskless. A bond fund that owns a mix of corporate and government securities might start out with a 5 percent yield, but in a tax-exempt IRA, you will save about one-fourth of the bite from inflation, taxes, and investment costs.

The lesson is clear: Investing outside of a tax-exempt or tax-deferred account is like foolishly pouring real money down the toilet.

Tax-Deferred Retirement Accounts

Set up and max out your IRA account. The limit you can set aside now is $2,000 a year each for you and your spouse, but that will rise to $5,000 a year by 2008. If you are over 50, you can take advantage of a catch-up provision by adding another $500 a year, and as much as $1,000 a year starting in 2006.

The big savings will be found in a 401(k) account. You can currently invest $11,000 tax-exempt each year, and that will increase by $1,000 a year up to a total of $20,000 a year. Just make sure you diversify. Don't “Enronize” your retirement by putting all your eggs in one crumbling basket.

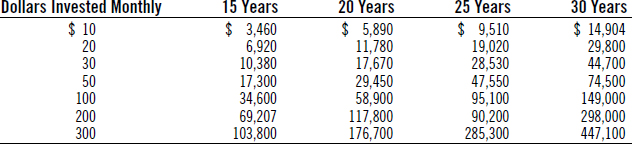

BIG OAKS FROM LITTLE ACORNS GROW

Table 3.2 can help you decide just how much you want to put away every month and for how many years. It shows you how unbelievably huge even small compounded amounts of money can grow to be at 8 percent in 15, 20, 25, and 30 years in a tax-exempt or tax-deferred account.

WHY THE POOR GET POORER

I recently saw a young mother at the supermarket with three children and a grocery cart full of beer, pop, cigarettes, frozen casseroles, and junk food that cost several times what the wholesome food in the same store would have cost them. After she paid for much of it with a credit card, she hauled it out to a 10-year-old jalopy and drove off.

Table 3.2 The Power of Compounding, Part II

I probably shouldn't judge her. Maybe she has an abusive, alcoholic husband. Maybe she's a divorcee or a widow or a deserted wife. The sad thing is that she doesn't have a clue about the principles we're talking about here. She's young, and in 20 or 30 years she could be very prosperous with a healthy balance sheet. The hard part would be to persuade her to change her whole perspective on money, and that is a monumental task.

We've all read the news stories of the manual laborer, maybe the janitor of the local school, who died and, to everyone's shock, left a fortune to a local church or charity—or pet cat. Where do such people get the money? They frugally and carefully saved, and usually the power of compounding took over.

This example strikes close to home. Kay's dad, Carl Felt, was the custodian at the local high school for years and managed to accumulate more than $45,000, which he was able to loan me at a time when my business needed it. (I doubled his money in a year.)

PAY YOURSELF FIRST

The biggest factor in your investment plan should be a generous savings program. Americans are saving at the lowest rate in history—just under 4 percent, up from only 3 percent in 2001. If you're serious about having a prosperous retirement, simply put aside in an interest-bearing account at least 10 percent of what you make every month! This may seem impossible to many of you, as there always seems to be too much month left at the end of your money, and expenditures tend to rise to meet income. The only way this will work is if you do it the minute you receive your paycheck. That will also discipline you to begin some of the economies I have discussed earlier in this chapter.

So what's the payoff for this kind of discipline? The average American family takes home about $3,000 a month. Saving 10 percent of that means $300 a month going into a money market fund or savings account. That's $3,600 a year. After 20 years of compounding at only 8 percent, that adds up to $176,700. In 25 years, it's $285,300. In 30 years, it's an amazing $447,100! Is that worth it?

This is pretty old-fashioned, fuddy-duddy stuff, and it's really out of style in today's live-it-up environment, but it has worked throughout history and it will work now and in the future. The math is inexorable—as sure as the rising and setting of the sun. The biggest problem is emotional: The payoff is long-term, and the sacrifices are right now. It takes maturity, a fundamental change of heart about the importance of material things in your life, a conscious decision to change your lifestyle, and a clear understanding of the value of long-term thinking as opposed to short-term thinking. It also doesn't hurt to have an attitude of gratitude for what you do have—an appreciation for the blessings that are so abundant in America. As you cultivate this attitude, you will find more contentment with less stuff, righteous pride in being increasingly debt-free, and a growing satisfaction in the security you are inexorably building for your old age. (And you won't be able to depend on Social Security to take care of you; see Chapter 6.)

As I wrote this chapter, I realized with a sinking feeling how few of the things I espouse here I have consistently applied to my own life. I have made really big bucks in my lifetime, and when the money was pouring in, it seemed endless and hard times seemed in another galaxy. But if I had saved 10 percent out of each paycheck and allowed the interest to compound, I would now have several million dollars more than I have now and would not have had to go through the financial roller coaster my life has been in recent years.

So, do as I say, not as I did. I don't have enough time left for the full power of compounding to work for me to the max (remember, sometimes I wish I was 72 again!), but Kay and I are now implementing the suggestions in this book. With a little luck, I might have 15 or 20 years to watch my own advice pay off. I have beaten cancer and a mild heart attack, so I'm pretty tough, and you probably couldn't kill me with an axe, and if I don't drive too fast and avoid sharp implements, I might live forever. Don't bet against it.