Chapter 8

The Bigger-Fool Theory of Investing

The stock-market bubble of the late 1990s inflated because investors (speculators?) assumed that if they paid a foolish price for a stock, they would be able to sell it to a bigger fool.

Ignoring the importance of intrinsic value in picking stocks to invest in during the 1990s is by far the most foolish thing done by the most investors during my quarter century as a financial publisher. It was a universal epidemic! It worked for awhile as the market soared to unsustainable heights, driven by investors (speculators?) who assumed that even if they paid a foolish price for a stock, a bigger fool would come along and pay them an even more foolish price. Understanding the importance of real value made fortunes for a few investors who were lucky enough or smart enough to sell at or before the peak of the bull market in March or April of 2000. They understood that at those prices, most stocks were worse than lousy values, and they would go higher only if investors were willing to pay ridiculously higher prices. But most Americans who bet on the biggest stock bubble since 1929 when it was full of lousy values still own their deflated stocks and mutual funds in individual investment accounts as well as in their 401(k)s, and have been hurt big time. As this is written, the carnage is far from over, and millions of investors are still holding onto their big losers like grim death, emotionally incapable of admitting they made a terrible value judgment, and hoping to just break even.

Sooner or later, stocks always “regress to the mean.” If they get too far out of line, either up or down, sooner or later they go back within the historic range of traditional measurements of value. The further they go above intrinsic value to the upside in an investment mania, the further they will overreact to a level well below intrinsic value on the downside near the bottom of a secular bear market. I will teach you how to measure these values so you know whether you are really investing or just counting on the bigger-fool theory to bail you out. I will also share my strategies for determining when the values are real and not illusory, and the world is truly on the bargain table.

For most of the 150-year history of the New York stock market, investing was a matter of selecting the shares of the companies that had the best management and business prospects for sales and earnings. It was assumed that if management took good care of the business, the price of the stock would do fine, and the investors would share in the profits through dividends and capital gains. Yes, speculators and traders would bet strictly on stock movements, using charts and other technical tools, and these speculating traders served the useful function of creating the short-term, in-and-out trading volume which created the necessary good liquidity for everyone else. But the speculators were a tough and hard-bitten bunch who knew exactly what they were doing and got an exciting emotional high from the potentially profitable risk. The vast majority of shareholders were conservative investors trying to make a good return from owning a piece of a successful business over the long term.

Sometime in the last two decades, however, investment slipped away from the Wall Street center stage, and speculation became the order of the day. Most people didn't sense the sea change, because they still called it “investment.” Actually, it was insanity, a mania that was near to a mass psychosis. Millions were subscribing to the bigger-fool theory. Those who should have been investors were really speculators and didn't know it. The Nasdaq bubble was created by this mentality. The hottest high-tech stocks had zero chance of profits in the foreseeable future; profits weren't even in their projections, but if they were, the underlying assumptions would make Pollyanna blush. If speculators' price expectations were met, those prices were way beyond levels that could have been supported by even the most wildly optimistic business scenarios. Buying stocks had nothing to do with investing in a company's drive toward a healthy bottom line; it only had to do with a soaring stock price, totally disconnected from the reality of true business success. Stock prices were totally detached from any objective measurement of business success. It had nothing to do with value. It was mass stupidity, speculating on price movement.

For some lucky ones, the road to financial heaven seemed to be paved with initial public offerings (IPOs) that only a few favored wealthy clients were able to buy as the companies apportioned them out to the brokers who used their allotments to reward their biggest clients. Money was doubled and tripled overnight, based on an airy foundation of dreams, hopes, and speculation, unfounded in any kind of reality. Some people got in at the start and sold out before the bubble burst. A few of the companies would become real businesses, but most of them started out as dot-coms, and now they are dot-gone!

During the late, lamented bull market of the 1990s, the term value was a hiss and a byword to most investors, and especially to analysts on Wall Street. It was a quaint, fuddy-duddy word that had no relevance to the market. Stocks were going up just because they were going up, and “momentum investing” was the new catchword of the day. Traditional measures of value, such as price/sales, price/earnings, and price/dividend ratios and profits were simply ignored. Many of the hot stocks of the last few years didn't even have a profitable bottom line built into their spreadsheets and projections; they would worry about that in the sweet by and by. All management wanted now was share of market and a soaring stock price at any cost, as they would only make their killing with their options if prices soared. Dividends now or in the future weren't even being talked about. If they ran out of cash, they assumed they just had to go into the hot venture capital market and get more. Then, when the market started its death spiral in April 2000 and the portfolios of the venture capitalists were devastated, the capital gravy train jumped the tracks, stung venture capitalists pulled in their horns, and company after company went under, starved for lack of cash, or became a mortally wounded, crippled basket case. People like me who refused to participate in the mania looked like fools for a long time; we seemed to be the stupid ones.

A lot of this phenomenon was created by our dysfunctional tax structure. For example, dividends are taxed twice at the highest rates—first by the corporate tax and second by the personal income tax when you get your dividend checks. Corporate executives did not want dividends; they wanted the company to retain its earnings (if there ever were any) and reward them with options, because that would result in more favorable tax treatment when they took their profits as capital gains. And with the hot market, they could make fortunes with their options, even if there were no business profits. That made the stock price the sole measurement of their personal wealth. This also led to the endemic fraud where deceptive accounting methods were chosen that would inflate the apparent profits, and thus the value of the stock, simply because the stock price was where the executive's bread was buttered, not the company's real bottom line.

Also, millions of Americans had no idea that they were pouring their money into an inflated bubble and a fragile stock market when they poured their money into stocks, mutual funds, and their 401(k)s, thinking they were simply buying into a safe savings program that would go up 20 percent a year. The ignorance was appalling, even bizarre. I can't tell you how many Ruff Times subscribers, knowing I was bearish, would assure me, “I'm not in the stock market, I'm in mutual funds,” or a 401(k), or whatever. Wall Street propaganda reinforced these dysfunctional attitudes, telling everyone to “buy on dips” and assuring them that the stock market always went up over “the long term,” whatever that was. They were burying the fact that even in many companies' published projections, there was no chance of enough profit to justify even current stock prices, let alone the higher prices bigger-fool theorists were betting on. Wall Street's institutional memory had poured down the memory hole the fact that past secular bear markets (long-lasting broad declines) had in some cases lasted as long as 15 to 20 years. If you bought near the top of the previous bull market, it could take that long to simply break even. There is an old Bible-derived adage which I have adapted to make my point: “There is a time to sow and a time to reap” ... and a time to run like hell, and it was now running time.

Optimism was the word of the day at the peak of the market in March and April of 2000. As I told you in Chapter 7, 98 percent of the recommendations coming from Wall Street analysts and investment advisors were “buy,” or “hold,” and less than 2 percent were “sell.” At that pivotal time, 98 percent “sells” would have been a much sounder strategy, as the falling tide lowered even the sounder boats, even as a bear market was still unthinkable on Wall Street. Most of the “analysts” making these calls were obsessed with the commissions they earned when people bought stocks, including the special deals the brokers got for selling an IPO to a customer. Most of these decisions were made by young whippersnappers who weren't even brokers during the last bear market and had no idea what happened historically during bear markets. To them, the traditional valuations of sales, earnings, and dividends were old-fogy ideas that weren't even in their vocabularies.

I recently had dinner with a very bright young man who told me he had put money in the stock market and his portfolio had fallen big time while he kept hoping for a rebound. He asked me what he should do. I told him to sell and put the money into Treasury Bonds because interest rates were going to fall even lower, and bonds always go up when interest rates go down. He said, “I can't do that. I would take a 50 percent loss.”

I said, “You have already taken your loss. I'm just asking you to face up to it and do something about it. There is only one legitimate question to ask yourself: ‘Given that I have a portfolio worth $XXXX, would I buy the stocks I own today? I have to avoid further losses and gain some profits.’ The paper losses you have now are history. The beginning of wisdom is to face reality.”

He then said, “Well, I'm just going to wait and see if I can get it back,” which told me that now the total purpose of his investing was to break even, which is not a really smart attitude for an investor when a stock has to double just to break even. You can break even with a lot less risk by putting the money in your mattress. The market dropped another 10 percent while the T-bonds rose 12 percent while yielding 6 percent interest or more!

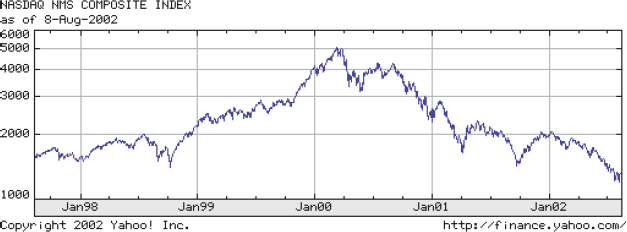

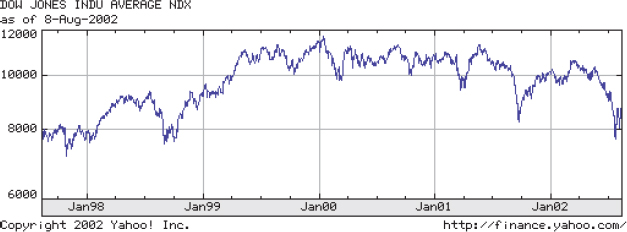

The out-of-sight traditional market measurements of valuation drove me to recommend in February and March of 2000 that everyone should sell all their stocks, even the “good companies,” because the falling tide would lower even the sound boats. I was laughed at by a thousand investors who thought I was a fool when I said this at a major investment conference, and frankly, I felt pretty stupid at the time, even though I knew it was the right thing to do. I told them that the Nasdaq was headed for 1,500 or less. It was about 5,000 at the time, and investors were betting that trees would grow to the sky (see Figure 8.1). Meanwhile, the Dow Industrials had peaked at 11,219 in January (see Figure 8.2) and had begun the slide that I believed would not end until it reached 4,500—possibly as low as 2,000, which was where it would go if the market returned to average historical valuations as measured by price/earnings, price/dividend, and price/sales ratios—which history said it would.

Figure 8.1 Nasdaq NMS Composite Index as of August 8, 2002. (Copyright 2002 Yahoo! Inc., http://finance.yahoo.com)

The Nasdaq has met my initial target, which I have now lowered to 1,000. The Dow hasn't hit my target yet as this is written, but has been down to just above 8,000, nearly 30 percent below where it was when I made my forecast. (See Figure 8.2.) (Late note: during 1983 the Dow rallied over 10,000. Even during secular bear markets, half the years are up years. The bear was just hibernating.)

Figure 8.2 Dow Jones Industrials Average Index as of August 8, 2002. (Copyright 2002 Yahoo! Inc., http://finance.yahoo.com)

We were way above the average valuations over the history of the market and a heck of a lot further away from the values that prevailed at the bottom of past bear markets. History taught me that this bear market would not end until it bottomed out at or below traditional valuations when pessimism was universal and it became irresistible to long-term investors because it was nearly riskless measured by price alone. If it bottomed well short of these levels, it would be the first bear market that ever ended without returning to real sanity.

WHY BUY STOCKS?

The purpose of buying stocks has changed dramatically in the last few years. Historically, you bought a stock to benefit from the growth of sales and profits. You were betting on the company and its management, not the market. Now investors (I hesitate to call them investors—they're really speculators) weren't investing in a company or a group of companies to participate in increased sales, and above all, profits. They weren't investing in companies, they were speculating on stock prices, assuming that trees would continue to grow to the sky and that the current psychology of investors would continue into the indefinite future, despite surreal valuations.

When the Nasdaq market started to collapse, some money managers started looking for “value.” At least most of the companies in the Dow Jones Industrial Average had some profits, whereas very few of the companies in the red-hot Nasdaq index had any or even the prospect of having any. So “sophisticated” money began to migrate from the Nasdaq to the Dow. But there was one hitch: Even though there was some value in the Dow stocks because they had real sales and earnings, they were also grossly overvalued by traditional measures. The bottom was a long way away, and the market would crash either in one fell swoop or in a slow-motion decline over the next months or even years, like being nibbled to death by ducks.

In the old fuddy-duddy days, if you invested in a company, you assumed the price would take care of itself if sales and earnings grew, so you bet on a management team that knew something more than financial engineering and were interested in something more than today's market value of their options. Wal-Mart is a great example of a company that treasures its bottom line. As this book is written, it is still overvalued, so I wouldn't buy it now, but they have the right idea—market effectively, make money, and eventually the market will reward you. Wal-Mart is on my list of future prospects when the price is right. The only thing wrong with Wal-Mart at the moment is the price.

What does all this boil down to? Be an investor, not a speculator, and especially not a “momentum investor”—or at least know what you really are. The odds are against the speculators, especially those who think they are investors but aren't. Don't buy stocks unless there are genuine values as measured by historical standards in the market as a whole, as well as the stock you are buying.

What are those standards and how do you measure them? When the market is finally fairly valued, the world will be on the bargain table. You will be able to tack The Wall Street Journal to the wall, throw darts at it, invest in the holes, and make money. Just be patient!

I would suggest that the price/earnings ratio (PE) for the whole New York Stock Exchange at historic bottoms is around 7/1. As this is written, the PE is about 32/1. At the bottoms, dividends yielded around 4 percent. As this is written, the yield is closer to 1 percent. When the market approaches these traditional historical bottoms, I'll report it in The Ruff Times (www.rufftimes.com). (See Appendix A.)